Abstract

Objective

The current study examines the variation in alcohol use among nightclub patrons under three transportation conditions: those who departed from a club using modes of transportation other than cars or motorcycles (e.g., pedestrians, bicyclists, subway riders); those who were passengers of drivers (auto/taxi passenger patrons); and those who drove from the club (driving patrons). We seek to determine whether patrons' choice for how to leave the club contributes to their risk, as assessed by blood alcohol concentrations (BAC), after controlling for other factors that may contribute to their BAC including demographic characteristics and social drinking group influences.

Methods

Data were collected from social drinking groups as they entered and exited clubs for 71 different evenings at ten clubs from 2010 through 2012. Using portal methodology, a research site was established proximal to club entrances. Each individual participant provided data on themselves and others in their group. The present analyses are based upon 1833 individuals who completed both entrance and exit data. Our outcome variable is blood alcohol content (BAC) based upon breath tests attained from patrons at entrance and exit from the club. Independent variables include method of transportation, social group characteristics, drug use, and personal characteristics. We use step-wise multiple regressions to predict entrance BAC, change in BAC from entrance to exit, and exit BAC: first entering individual demographic characteristics, then entering group characteristics, then drug use, and finally entering method of transportation (two dummy coded variables such that drivers are the referent category).

Results

In sum, in all three of our analyses, only three variables are consistently predictive of BAC: presence of a group member who is frequently drunk and non-driving modes of transportation, either being the passenger or taking alternate methods of transportation. In particular, taking an alternate form of transportation was consistently and strongly predictive of higher BAC.

Conclusions

Additional public health messages are needed to address patrons who are no longer drinking and driving but who are nonetheless engaged in high levels of drinking that may lead to various risky outcomes, for example: being targeted for physical and/or sexual assault, pedestrian accidents, and other adverse consequences. These risks are not addressed by the focus on drinking and driving. Key messages appropriate for patrons who use alternate transportation might include devising a safety plan before entering the club and a focus on sobering up before leaving.

Keywords: Designated drivers, Drunk walking, Alcohol pre-loading, Public transportation

1. Introduction

Research in the U.S. concerning alcohol use and methods of transportation has focused primarily on prevalence of and interventions on drinking and driving (Caudill, Harding, & Moore, 2000; Harding, Caudill, & Moore, 2001; Rivara et al., 2007). Based upon prior research findings, effective interventions need to target passengers as well as drivers (Cartwright & Asbridge, 2011; Johnson, Voas, & Miller, 2012) to understand the dynamics of drinking groups (individuals who arrive at and leave drinking establishments together) in order to enhance the effectiveness of risk reduction efforts among young adults ages 18–25 (Johnson et al., 2012; Lange, Reed, Johnson, & Voas, 2006). These young adults are in the age group with the highest percentage of drivers in crashes who are under the influence of alcohol (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2012, April). The efforts to prevent injuries resulting from driving under the influence of alcohol have been generally effective. With the combined efforts of activism, public health campaigns, and increased policy and enforcement efforts, alcohol-related driving deaths have declined over the past three decades (US Department of Transportation, 2008; Wells, Kelly, Golub, Grov, & Parsons, 2010).

However, public health campaigns that emphasize the “don't drink and drive” message have been criticized for unintentionally sending a message that, as long as you don't drink and drive or ride with an impaired driver, you can drink to excess while out for the evening and be safe (Ditter et al., 2005; Harding et al., 2001). In addition, the focus on vehicle-related safety overlooks other fundamental issues related to alcohol use and exiting a drinking venue safely when private vehicles are not involved, such as taking the subway, walking or riding a bicycle. These concerns include: choosing dangerous levels of alcohol consumption; increased risk of pedestrian-auto accidents; and an increased risk for involvement (both victimization and perpetration) in petty/misdemeanor and serious crimes in the area surrounding the drinking establishment.

1.1. Choosing dangerous levels of alcohol consumption

First, passengers in drinking groups who have chosen a designated driver may reduce their normal concern with heavy drinking; thereby raising their risk of drinking to intoxication or acute intoxication (alcohol poisoning). Some argue that the relationship between designated drivers and passenger consumption is unclear, in that heavier drinkers are more likely to avoid legal consequences of driving under the influence by strategies other than a designated driver such as: taking a cab, walking, or simply relying on a friend who has had less to drink (Caudill, Rogers, Howard, Frissell, & Harding, 2010). However, one laboratory study (Rivara et al., 2007) found that the use of a designated driver resulted in almost half of the participants (ages 21–34) drinking more on that occasion than they usually drink. More than a third of the participants drank at least three more drinks than they usually drank when a designated driver was present. Another lab study (Harding et al., 2001) found that small but significant percentages (15–30%) converted from a typically low blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.08 to a high BAC (0.11) because there was a designated driver. It should be noted that this study defined “lower risk” as BAC < .10 and “higher risk” as BAC ≥ .10, which varies from the current U.S. legal definition of intoxication as a BAC ≥ .08 and the recent recommendation from the National Transportation Safety Board that the legal limit for driving be lowered to a BAC ≥ .05 (National Transportation Safety Board, 2013). In studies where naturally formed groups were used, cueing drivers to the risks of drunk driving significantly decreased their BAC (Johnson & Clapp, 2011) while cueing riders to know their limits on drinking increased their BAC, with those in a group who had increased expectations for group drinking correspondingly having higher BACs (Lange et al., 2006).

1.2. Risk of pedestrian-auto accidents

In addition, there is a higher risk for those leaving bars and clubs under the influence of alcohol and on foot to be in more (and more severe) pedestrian accidents involving autos. A study of pedestrian accidents in Vancouver found 32 hotspots; 21 (65%) of the hotspots were in the immediate vicinity of bars (Schuurman, Cinnamon, Crooks, & Hameed, 2009). Among pedestrians in auto-involved accidents, those who had used any alcohol (BAC > .01) were more likely to make risky decisions about street crossing (against the signal, midblock) and had higher severity of injuries and longer hospital stays (Dultz et al., 2011). In a study to assess contributors to various forms of trauma among Emergency Room patients, the presence of a BAC greater than .20 was a significant predictor of those who were injured in pedestrian-auto accidents, but was not a predictor of those injured through other forms of trauma (Ryb, Dischinger, Kufera, & Soderstrom, 2007).

1.3. Risk for involvement in petty/misdemeanor and serious crimes

Finally, bars are a well-documented area for increased levels of crime (Brower & Carroll, 2007) as intoxicated individuals are outside and within close proximity to the venue. Rates of nonviolent crime (vandalism, nuisance crime, public alcohol consumption, driving while intoxicated, and underage alcohol possession/consumption.) and violent crime (assault, rape, robbery, and total violent crime) are related to the density of alcohol establishments, with stronger associations found for on-premise consumption locations, such as bars and clubs (Toomey, Erickson, Carlin, Lenk, et al., 2012; Toomey, Erickson, Carlin, Quick, et al., 2012). Further, in a study of the expanded weekend hours of the Washington DC Metro system, Jackson and Owens (2011) found that the number of drunk-driving arrests were reduced with expanded availability of trains running in late night hours but also found there was an increase in alcohol-related arrests for nuisance crimes (e.g. simple assault, urinating in public, obscene gestures, drinking in public, possession of open alcohol containers or defacing a building) in neighborhoods surrounding the bars. Thus, attending to one type of drinking problem can displace alcohol-related public health problems into other areas.

In sum, the trend of decreases in drinking and driving, coupled with research suggesting that use of non-driving strategies such as using a designated driver is related to increases alcohol use among passengers (Johnson et al., 2012; Rivara et al., 2007), give reason to suspect that drinking non-drivers/non-passengers constitute a group that is at risk for negative outcomes.

Nightclubs present an ideal environment for examining these risks as there are drivers, passengers, and persons using alternate transportation with high rates of intoxication upon exiting the clubs (Johnson et al., 2012). Miller et al. (2009) and Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Johnson, and Voas (2013) found that one third of patrons exiting clubs were legally intoxicated (BAC ≥ 0.08). The current study examines alcohol use among club patrons under three transportation conditions: those who departed from a club using modes of transportation other than cars or motorcycles (e.g., pedestrians, bicyclists, subway riders); those who were passengers of drivers (auto passenger patrons including taxis); and those who drove from the club (driving patrons). Specifically, this study proposes to develop a better understanding of those who choose to take alternate forms of transportation. We seek to determine whether their choice for how to leave the nightclub relates to their risk, as assessed by blood alcohol concentration (BAC), after controlling for other factors that may contribute to their BAC. This includes demographic characteristics and social drinking group influences as our prior work has indicated (Johnson et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2013). In addition, we need to consider that many club patrons often arrive at the club “front-” or “pre-loaded”(Forsyth, 2010; Graham et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2013; Voas et al., 2006). A recent study of club patrons found that 54.9% arrived at the club having consumed alcohol and half of those were impaired or intoxicated (26.3% of the total sample had BAC > .05) (Miller et al., 2013). That is, a number of club goers drink before arriving at the club so that entrance BAC level is contributing to their exit BAC level. Therefore, to better understand the level of risk for patrons leaving a club, we must consider the BAC at entrance, in addition to the amount they drink while in the club, combining to create exit BAC and thus exit risk.

2. Methods

Data were collected from patrons as they entered and exited clubs for 71 different evenings (hereafter referred to as events) at ten clubs from 2010 to 2012 in San Francisco. Clubs were selected based upon the following criteria: (1) Electronic Music Dance Events (EMDEs (Johnson et al., 2012)) were featured; (2) events typically attracted a minimum of 200 patrons; and (3) management agreed to the data collection. Initially, clubs that had been randomly identified in a prior study were recruited. To supplement this list, experts in the local entertainment industry were enlisted to provide additional clubs meeting these criteria. From a total of 13 clubs that were contacted, agreement to conduct the research was obtained at ten sites. Events reflect different types of electronic music (e.g., Industrial, House), and were promoted to attract different types of patrons (e.g., Latinos, lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender, younger patrons). Each club served as a research site a minimum of three nights and a maximum of ten nights.

2.1. Sample

A total of 2099 individuals enrolled in the study during this time period. The present analyses are based upon 1833 individuals (87.3%) who provided both entrance and exit data and also eliminates individuals (n = 9) who had entrance and exit data but did not respond to the transportation question. Comparisons between patrons who were missing exit data and patrons who had both entrance and exit data on variables used in these analyses revealed the following statistically significant differences: patrons with both entrance and exit data arrived at the club in larger groups (2.95 vs. 2.65) and had lower BAC entry levels (.03 vs. .04), as compared to patrons with entrance only data. There were no significant differences between these groups on any other items (Miller et al., 2013).

For the sample in these analyses, the average age is 27.7 (SD = 7.60) with 48.4% under the age of 26. About half are male (51.4%). Most are heterosexual (71.9%) and less than half are in a relationship currently (40.4%). Although this is a sample largely exposed to college (87.2% have some college or more), most are not currently students (59.8%). The majority are employed full-time (54.0%).

2.2. Procedures

A research site was established proximal to the club entrance with a team of 8–10 research staff. Using portal methodology established in earlier club and other venue-based studies (Miller et al., 2009, 2013; Voas et al., 2006), we approached patrons on the sidewalk by recruiting the first person who crossed an imaginary line on the sidewalk, as they approached the club entry. We used a brief verbal approach, asking patrons if they would be willing to participate in a confidential and anonymous study on nightlife safety for which they would receive $30.00 ($10 at entrance, $20 at exit). Patrons that expressed interest in learning more about the study were escorted to the research area where interviewers provided more details. Consent forms were read to participants and verbal consent was provided. No signatures were gathered on consent forms to ensure anonymity. Copies of the consent form were made available to participants.

Outdoor recruitment is difficult and approximately 40% of the people we approached did not stop to listen to our recruitment efforts and did not permit us to determine their eligibility. Of the patrons verbally informed and eligible (i.e., going to the club and not just walking down the street, not working at the club), approximately two thirds (63%) participated. Refusal rates varied widely across events and across clubs. The primary reasons for refusal included: patrons were in a hurry (53%), patrons were hesitant to provide data (14%), and environmental factors (e.g., “too cold”) (8%). Blankets were provided to address this latter concern as many female club attendees were scantily clothed.

Patrons were issued a wrist band with a unique identifier that allowed linking entrance and exit data without personal identifiers to allow for anonymous data collection. At entrance and at exit, four types of data were collected: (1) verbal interview conducted by the research assistant, (2) paper and pencil self-administered survey, (3) oral assays for drug tests, and (4) Breathalyzer tests for determining estimates of blood alcohol concentration. As required of all National Institutes of Health funded grants, there was an Institutional Review Board approval prior to the initiation of data collection.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Alcohol use

Patron alcohol use was defined as the level of alcohol present in breath tests from patrons at entrance and exit. The construct was measured through biological sampling of Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) with breath samples, collected using the Intoxilizer 400PA™ (CMI, Inc., Owensboro, KY). For these analyses, BAC is a continuous variable. In the discussion of the results of this paper, three levels of alcohol consumption are defined: low, impaired, and intoxicated. Low consumption is defined as BAC < 0.05. Impairment is defined as BAC ≥ 0.05 and <0.08. Intoxication is defined as BAC ≥ 0.08 and meets the legal definition of intoxication for driving. In addition, we used results of the oral drug assays as alcohol and drug use tend to co-occur in clubs and serve as a control in this study. There are no threshold measurements for being impaired by drugs and some drugs can result in positive tests despite having been consumed days before. Given those constraints, we dichotomized the responses such that testing positive for any drug was scored ‘1’ and testing negative for all drugs was scored ‘0’.

2.3.2. Method of transportation

Method of transportation was defined as the mode of transport used by patrons to depart from the clubs, as reported to interviewers when exiting the club. Patrons reported how they were leaving the club that evening with response options: driving a car or motorcycle; riding with someone else; taking the buses or subway; riding a bike or walking; taking a taxi. From these data, three ‘method of transportation’ categories were identified: drivers, passengers, and alternate transportation users. Drivers were defined as anyone who indicated that they were leaving the club by driving a car or motorcycle. Passengers were defined as anyone leaving the club by riding with a driver of a car or motorcycle or taking a taxi. Those who used alternate transportation were defined as anyone who reported leaving the club on a mode of transport other than a car or motorcycle. This item was assessed during the exit interview only.

2.3.3. Social group characteristics

Based on prior work (Johnson et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2013), four group characteristics were assessed: concern for safety, presence of a responsible group member, presence of a problematic drinker, and size of group. Responses to the question about the participants' concern for safety of their social drinking group (“To what extent are you concerned about the group's safety tonight?”) formed a U-shaped curve with the majority of responses falling at the ends of the Likert responses. Therefore responses were combined and dichotomized (no/little as 0 and some/much as 1). Participants were asked if there was anyone who takes responsibility for the group (“Does anyone typically take responsibility for the safety of the group members?”). A response indicating that there was no responsible party or that the participant was unsure was given a value of 1 and a response where at least one individual was identified was given a value of 0. Participants were asked if there was a potentially problematic drinker in their group for the evening (Is there any member of the group who frequently gets drunk when s/he goes out?). Responses of no were given a value of 0 and yes were given a value of 1. Finally, because individuals were often attending the clubs in groups, we calculated group size by summing the number of respondents within the group.

2.3.4. Personal characteristics

As with social group characteristics, our prior work indicated that a number of demographic items are potentially important contributors (Johnson et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2013). Personal characteristics were measured through a series of questions that were collected in the self-reported entrance surveys and interviews. The variables were coded as follows: gender (0 female and 1 male), age (year of birth subtracted from the year of data collection to create a continuous variable), race (0 White and 1 for American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Black or African American, Other), non-Hispanic ethnicity (0 Hispanic or Latino and 1 not Hispanic or Latino), income (Likert ordinal scale recoded to midpoints to create a continuous variable), education (0 less than college education and 1 college degree or more), employment status (0 full-time and 1 part-time or unemployed), student status (0 not a student and 1 part-time or full-time student), marital status (0 not married and 1 married), single relationship status (0 in a relationship and 1 not in a relationship), and minority sexual orientation (0 heterosexual and 1 LGBT [gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender]).

2.4. Analyses

Analyses to assess group differences included one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Chi-square for categorical variables. For these analyses, the original item responses for demographic variables were used. To address the ability of the method of transportation to predict BAC level (a continuous variable), we used step-wise multiple regression: first entering individual demographic characteristics, then entering group assessments, and finally entering method of transportation (two dummy coded variables such that drivers are the referent category).

3. Results

3.1. Transportation status group characteristics

Of the 1833 participants, 24.6% reported being drivers (n = 451), 61.0% were passengers in private vehicles or taxis (n = 1118), and 14.4% (n = 264) reported alternate transportation methods. Of those who were passengers, most were passengers in cars (68.2%) rather than taxis (31.8%). Of those who were classified as alternate transportation users: 62.1% (n = 164) walked or took a bicycle; 29.9% (n = 79) planned to use the subway; 6.1% (n = 16) reported more than one transportation method (e.g., subway and walking); and 1.9% (n = 5) reported “other”.

3.2. Transportation status group characteristic differences

Comparisons between the transportation groups were conducted to determine if the patrons differed significantly on demographic characteristics, group characteristics, and entrance/exit BAC levels (see Table 1). For continuous variables, post hoc analyses indicate which groups were significantly different from each other. On all demographics except relationship and student status, there are significant differences between the three groups.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics N = 1833.

| 24.6% | 61.0% | 14.4% | χ2 or F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 30.0b,c | 27.1a | 26.5a | 28.9** |

| Size of group | 2.7b | 3.1a,c | 2.8b | 13.5** |

| Mean Income (×$1000) | 39.8b,c | 34.6a | 34.3a | 6.0** |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 42.4 | 52.4 | 38.8 | 26.1** |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 77.6 | 75.8 | 59.7 | 33.6** |

| Gay/lesbian | 16.4 | 16.1 | 28.9 | |

| Bisexual | 5.9 | 8.1 | 11.5 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 31.8 | 34.1 | 45.2 | 29.6** |

| Asian | 19.3 | 18.2 | 8.4 | |

| Black | 10.5 | 8.3 | 7.6 | |

| Hispanic | 24.0 | 26.7 | 25.1 | |

| Other | 5.4 | 6.2 | 5.7 | |

| Multiracial | 9.0 | 6.6 | 8.0 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time | 57.9 | 52.5 | 54.4 | 10.2* |

| Part-time | 23.5 | 22.9 | 18.6 | |

| Unemployed | 18.6 | 24.5 | 27.0 | |

| Student status | ||||

| Full-time Student | 25.3 | 26.6 | 30.7 | 4.2 |

| Part-time Student | 14.4 | 13.4 | 10.2 | |

| Not a student | 60.2 | 60.1 | 59.1 | |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 24.1 | 20.1 | 17.1 | 7.8 |

| In a relationship | 20.0 | 19.4 | 21.7 | |

| Dating | 25.8 | 25.1 | 25.5 | |

| Not dating | 30.1 | 35.4 | 35.7 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Drivers

Passengers

Alternate methods

3.2.1. Demographic differences

The alternate transportation group had the highest percentages of patrons who were gay or lesbian (28.9%), bisexual (11.5%), White (45.2%), unemployed (27.0%), and the lowest percentage that were heterosexual (59.7%), Asian (8.4%), Black (7.6%), and employed part-time (18.6%). They had the lowest mean income (M = $34 K). Passengers had the highest percentage of females (52.4%), Hispanic (26.7%), White (34.1%) and Other Race (6.2%) members and the largest groups (M = 3.1). Passengers also had the lowest percentage who were gay or lesbian (16.1%), bisexual (8.1%) and employed full-time (52.5%). Drivers were significantly older (M = 39.8), were members of smaller social drinking groups (M = 2.7), and had the highest mean income (M = $42.4 K) compared to patrons using the other two transportation methods (who were not significantly different from each other). Drivers were most likely to be Asian (19.3%), Black (10.5%), Multiracial (9.0%), and heterosexual (77.6%), and were the least likely to be unemployed (18.6%) or bisexual (5.9%).

3.2.2. Social group differences

Additionally, patrons using alternate transportation had the highest percentage of those reporting having a frequently drunk member (67.7%), had the highest percentage that could not identify a group member who takes responsibility (43.8%), yet the lowest percentage reporting concern for the group's safety (39.7%). Patrons who were drivers had the highest percentage who reported having someone who takes responsibility for the group (76.4%), the highest percentage of individuals concerned for the group's safety (49.2%), and the lowest percentage of individuals who reported having a regularly drunk member in the group (47.7%).

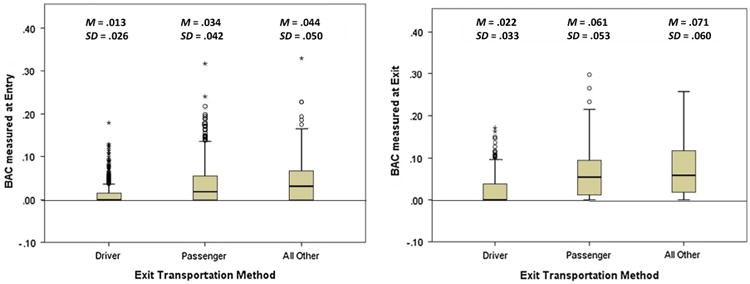

3.2.3. Alcohol and drug consumption differences

The groups were not significantly different on drug use at entry or exit, with 18–24% of each group testing positive at entry and 21–27% testing positive at exit. Most notably, each transportation group was significantly different from the other two groups on entrance mean BAC and exit mean BAC, with alternate transportation the highest and drivers the lowest (see Fig. 1 and Table 2). On average, patrons who used alternate forms of transportation entered the clubs at the highest average BAC (M = .04); passengers and drivers entered the club with significantly lower BACs (passengers M = .03 and drivers M = .01). Patterns at exit mirrored entrance patterns for average BACs. Patrons who used alternate forms of transportation left the clubs nearly legally intoxicated (M = .07), passengers left the club impaired (M = .06), and drivers left the club with low alcohol use (M = .02). Change in BAC from entrance to exit was significantly different for drivers but not the other two groups. Of concern is the range of BAC for all groups. Drivers had a maximum value over twice the legal limit (.17) while entrance maximum BACs for the other two groups were even more dangerously high, with passengers at .32 and alternate transport users at .33. All three groups had individuals of great concern but the highest BAC recorded among the driver category was still significantly lower than the passenger or alternative transportation groups.

Fig. 1.

Distributions of blood alcohol concentration by exit transportation method (entry and exit).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics N = 1833.

| 24.6% | 61.0% | 14.4% | χ2 or F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrance BAC | .013b,c | .034a,c | .044a,b | 60.8** |

| Range | .000–.179 | .000–.317 | .000–.330 | |

| Change in BAC | .009b,c | .027a,c | .027a,b | 116.6** |

| Range | −.137 to .122 | .147–.168 | −.260 to .168 | |

| Exit BAC | .022b,c | .061a | .071a | 37.3** |

| Range | .000–.172 | .000–.297 | .000–.257 | |

| Concern about group safety | ||||

| None/little | 50.8 | 53.7 | 60.3 | 5.9* |

| Some/very | 49.2 | 46.3 | 39.7 | |

| Someone takes responsibility | ||||

| No/DK | 23.6 | 27.2 | 43.8 | 35.4** |

| At least one person | 76.4 | 72.8 | 56.2 | |

| One frequently drunk member | ||||

| No | 46.7 | 37.8 | 29.3 | 49.2** |

| Yes | 47.7 | 61.1 | 67.7 | |

| Positive drug test | ||||

| Entry | 18.4 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 4.5 |

| Exit | 21.3 | 26.2 | 27.3 | 4.8 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Drivers

Passengers

Alternate methods

3.3. Predictive power of method of transportation on entry, change and exit BAC

To determine if transportation status predicts participants' BAC throughout the evening, three step-wise multiple regressions were conducted. For entry BAC four steps: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) group characteristics; (3) drug use; and (4) transportation method. For the change in BAC from entry to exit five steps: (1) entry BAC; (2) demographic characteristics; (3) group characteristics; (4) drug use; and (5) transportation method. For exit BAC four steps: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) group characteristics; (3) drug use; and (4) transportation method. Therefore, we were able to assess the degree to which transportation choice is predictive of participants' BAC (entry, club consumption, and cumulative BAC level at exit) after controlling for demographic characteristics, social drinking group characteristics, and drug use, all of which might contribute to this risk.

In all three of our analyses, only three variables were consistently predictive of BAC: reporting having a frequently drunk group member and both non-driving modes of transportation (being the passenger of a driver or taking alternate methods of transportation). In particular, taking an alternate form of transportation was consistently and strongly predictive of higher blood alcohol concentration. In addition, the model with the greatest variance explained is the change in BAC, indicating that the variables in our equations, especially transportation status, are most illuminating with regard to the amount of alcohol consumed while in the nightclub.

Our first regression examines the relationship of method of transportation on entry level BACs after controlling for demographic and group characteristics as well as drug use (see Table 3 for coefficients and changes in R2). After Step 1, inclusion of demographic variables alone was significantly predictive of BAC. Adding group characteristics (Step 2) significantly increased R2 as did drug use (Step 3). Finally, adding transportation status (Step 4) also significantly increased R2. In the final model, significant predictors of BAC level at entrance included age (younger age at higher risk), sexual orientation (LGBT at higher risk), race (White at higher risk), income (higher income), larger group size, increased concern about group safety, positive report of a frequently drunk group member, and testing positive for drugs. Variables assessing arriving as a passenger and alternate transportation were the strongest predictors of high entry BAC levels.

Table 3.

Multiple regression predicting entry BAC (demographics, group characteristics, drug use, transportation method).

| N = 1414 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | |

| (Constant) | 6.28 | .64 | 9.80** | 4.30 | .73 | 5.86** | 3.90 | .73 | 5.32** | 1.65 | .77 | 2.15 | ||||

| Age | −0.10 | .02 | −.18 | −5.56** | −0.09 | .02 | −.15 | −4.69** | −0.09 | .02 | −.02 | −4.86** | −.07 | .02 | −.11 | −3.61** |

| Gender (female referent) | 0.20 | .22 | .02 | 0.87 | 0.09 | .22 | .01 | 0.42 | −0.03 | .22 | .00 | −0.02 | 0.08 | .22 | .01 | 0.35 |

| Sexual orientation (heterosexual referent) | 1.20 | .24 | .13 | 4.93** | 1.24 | .24 | .13 | 5.12** | 1.20 | .24 | .13 | 5.01** | 1.04 | .24 | .11 | 4.41** |

| Race (white referent) | −1.45 | .26 | −.17 | −5.65** | −1.40 | .26 | −.16 | −5.46** | −1.39 | .26 | −.16 | −5.42** | −1.29 | .25 | −.15 | −5.14** |

| Ethnicity (hispanic referent) | −0.75 | .28 | −.08 | −2.64** | −0.76 | .28 | −.08 | −2.71** | −0.73 | .28 | −.08 | −2.62** | −0.65 | .27 | −.07 | −2.40* |

| Student status (non-student referent) | −0.32 | .27 | −.04 | −1.18 | −0.28 | .26 | −.03 | −1.05 | −0.19 | .26 | −.02 | −0.71 | −0.06 | .26 | −.01 | −0.22 |

| Employment status (full-time referent) | 0.06 | .27 | .01 | 0.23 | 0.07 | .27 | .01 | 0.26 | 0.04 | .27 | .00 | 0.14 | 0.04 | .26 | .01 | 0.16 |

| Education Level (less than college referent) | 0.54 | .24 | .06 | 2.22* | 0.49 | .24 | .06 | 2.01* | 0.62 | .24 | .07 | 2.56* | 0.55 | .24 | .07 | 2.34* |

| Income | 0.02 | .01 | .11 | 3.18** | 0.02 | .01 | .12 | 3.35** | 0.02 | .01 | .12 | 3.50** | 0.02 | .01 | .12 | 3.65** |

| Marital status (single referent) | −0.41 | .29 | −.04 | −1.39 | −0.44 | .29 | −.04 | −1.52 | −0.37 | .29 | −.04 | −1.29 | −0.28 | .28 | −.03 | −1.01 |

| Relationship status (no relationship referent) | −0.01 | .25 | −.00 | −0.05 | −0.02 | .25 | −.00 | −0.06 | 0.08 | .25 | .01 | 0.31 | 0.01 | .24 | .00 | 0.03 |

| Size of social group | 0.28 | .08 | .10 | 3.64** | 0.28 | .08 | .10 | 3.67** | 0.25 | .08 | .08 | 3.27** | ||||

| Concern about group safety | 0.37 | .23 | .04 | 1.63 | 0.38 | .22 | .05 | 1.70 | 0.46 | .22 | .05 | 2.09* | ||||

| Someone takes responsibility for safety (yes referent) | −0.11 | .25 | −.01 | −0.44 | −0.06 | .25 | −.01 | −0.24 | 0.15 | .25 | .02 | 0.60 | ||||

| Frequently drunk group member (no referent) | 0.97 | .19 | .13 | 5.13** | 0.95 | .19 | .13 | 5.04** | 0.83 | .19 | .11 | 4.47** | ||||

| Drug use | 1.67 | .25 | .12 | 4.71** | 1.05 | .24 | .11 | 4.32** | ||||||||

| Passenger | 1.83 | .26 | .21 | 7.13** | ||||||||||||

| Non-private transportation method | 2.58 | .37 | .21 | 7.07** | ||||||||||||

| R2 = .07, | R2 = .10, ΔR2 = .03, | R2 = .11, ΔR2 = .01, | R2 = .15, ΔR2 = .04, | |||||||||||||

| F(11,1399) = 9.1** | F(4,1395) = 10.0** | F(1,1394) = 10.8** | F(2,1392) = 13.7** | |||||||||||||

p < .05.

p< .01.

In the second regression, we examine the relationships of method of transportation on the changes in the BAC from entrance to exit after controlling for demographic and group characteristics (Table 4 details coefficients and changes in R2). In Step 1, entry BAC was entered as a control in order to assess change in BAC. The addition of demographic variables (Step 2) did not increase the R2 significantly. Adding group characteristics (Step 3) significantly increased R2. Adding drug use (Step 4) did not increase R2 significantly. Finally, adding transportation status (Step 4) also significantly increased R2. In the final model, after considering entry BAC, significant predictors of drinking in the club included older age, relationship status (no relationship), positive report of a frequently drunk group member, and both non-driver transportation methods. Method of transportation variables were among the strongest predictors of change in BAC for both passengers and patrons who used alternate modes of transportation.

Table 4.

Multiple regression predicting change in BAC from entrance to exit (entry BAC, demographics, group characteristics, drug use, transportation method).

| N = 1414 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | |

| (Constant) | 2.79 | .13 | 21.7** | 3.40 | .63 | 5.43** | 3.08 | .71 | 4.35** | 2.98 | .71 | 4.20** | 0.46 | .73 | 0.64 | |||||

| Entry BAC | 0.87 | .02 | .69 | 35.6** | 0.86 | .03 | .68 | 34.01** | 0.84 | .03 | .67 | 33.04** | 0.84 | .03 | .66 | 32.62** | 0.78 | .03 | .62 | 30.89** |

| Age | 0.01 | .02 | .01 | 0.39 | 0.01 | .02 | .02 | 0.65 | 0.01 | .02 | .01 | 0.59 | 0.03 | .02 | .05 | 1.94 | ||||

| Gender (female referent) | −0.28 | .21 | −.03 | −1.35 | −0.35 | .21 | −.03 | −1.64 | −0.38 | .21 | −.04 | −1.76 | −0.25 | .21 | −.02 | −1.20 | ||||

| Sexual orientation (heterosexual referent) | 0.40 | .23 | .03 | 1.74 | 0.38 | .23 | .03 | 1.63 | 0.38 | .23 | .03 | 1.61 | 0.31 | .23 | .03 | 1.36 | ||||

| Race (White referent) | −0.24 | .25 | −.02 | −0.96 | −0.12 | .25 | −.01 | −0.48 | −0.12 | .25 | −.01 | −0.48 | −0.11 | .24 | −.01 | −0.45 | ||||

| Ethnicity (hispanic referent) | −0.41 | .27 | −.03 | −1.53 | −0.41 | .27 | −.03 | −1.54 | −0.41 | .27 | −.03 | −1.52 | −0.36 | .26 | −.03 | −1.38 | ||||

| Student status (Non-student referent) | −0.42 | .25 | −.04 | −1.66 | −0.42 | .25 | −.04 | −1.65 | −0.39 | .25 | −.04 | −1.55 | −0.23 | .24 | −.02 | −1.38 | ||||

| Employment status (full-time referent) | −0.13 | .26 | −.01 | −0.51 | −0.14 | .26 | −.01 | −0.55 | −0.15 | .26 | −.01 | −0.58 | −0.16 | .25 | −.02 | −0.65 | ||||

| Education level (less than college referent) | 0.15 | .23 | .01 | 0.65 | 0.12 | .23 | .01 | 0.51 | 0.16 | .23 | .02 | 0.68 | 0.10 | .22 | .01 | 0.45 | ||||

| Income | .00 | .01 | .00 | −0.05 | 0.00 | .01 | .00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | .01 | .00 | .12 | 0.00 | .01 | .01 | 0.46 | ||||

| Marital status (single referent) | −0.36 | .28 | −.03 | −1.31 | −0.36 | .28 | −.03 | −1.30 | −0.34 | .28 | −.03 | −1.23 | −0.25 | .27 | −.02 | −0.94 | ||||

| Relationship status (no relationship referent) | −0.26 | .24 | −.02 | −1.09 | −0.27 | .24 | −.02 | −1.13 | −0.24 | .24 | −.02 | −1.01 | −0.32 | .22 | −0.03 | −1.39 | ||||

| Size of social group | 0.05 | .07 | .01 | 0.71 | 0.05 | .07 | .01 | 0.72 | 0.02 | .07 | .00 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| Concern about group safety | −0.07 | .21 | −.01 | −0.32 | −0.06 | .21 | −.01 | −0.29 | 0.04 | .21 | .00 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| Someone takes responsibility for safety (yes referent) | −0.40 | .24 | −.03 | −1.69 | −0.39 | .24 | −.03 | −1.63 | −0.20 | .23 | −.02 | −0.85 | ||||||||

| Frequently drunk group member (no referent) | 0.63 | .18 | .07 | 3.46** | 0.63 | .18 | .07 | 3.45** | 0.55 | .18 | .06 | 3.10** | ||||||||

| Drug use | .34 | .24 | .03 | 1.42 | 0.25 | .23 | .02 | 1.07 | ||||||||||||

| Passenger | 2.45 | 0.25 | .22 | 9.91** | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-private transportation method | 2.69 | .35 | .18 | 7.66** | ||||||||||||||||

| R2 = .47, | R2 = .48, ΔR2 = .01, | R2 = .49, ΔR2 = .01, | R2 = .49, ΔR2 = .00 | R2 = .52, ΔR2 = .04 | ||||||||||||||||

| F(1,1409) = 1267.2** | F(11,1398) = 107.3 | F(4,1394) = 82.2** | F(1,1391) = 77.5 | F(2,1391) = 80.1** | ||||||||||||||||

p < .05.

p< .01.

Finally, our last regression assesses the relationship of method of transportation on the cumulative BAC level at exit after controlling for demographic and group characteristics, thus reflecting the cumulative BAC at exit that reflects the pre-loading and drinking in the club. This is the ultimate level of risk from drinking that can impact safely exiting the club (Table 5 details coefficients and changes in R2). After Step 1, demographic variables were significant predictors. Adding group characteristics (Step 2) significantly increased R2 As did testing positive for drugs during the night (Step 3). Finally, adding method of transportation (Step 4) also significantly increased R2. In the final model, significant predictors included sexual orientation (LGBT at higher risk), race (White at higher risk), income (higher income), marital status (not married), and romantic relationship (not in a relationship). In addition, having a frequently drunk group member and testing positive for drugs were significant. Mode of transportation variables were the strongest predictors of exit BAC. The variables indicating passenger status and alternate transportation status were significant predictors for high BAC at exit.

Table 5.

Multiple regression predicting exit BAC (demographics, group characteristics, drug use, transportation method).

| N = 1414 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | B | SE | β | t | |

| (Constant) | 8.79 | .82 | 10.72** | 6.71 | .93 | 7.19** | 6.25 | .93 | 6.69** | 1.76 | .95 | 1.86 | ||||

| Age | −0.08 | .02 | −0.11 | −3.45** | −0.06 | .02 | −0.08 | −2.61** | −0.06 | .02 | −.09 | −2.75** | −0.02 | .02 | −.02 | −0.80 |

| Gender (female referent) | −0.12 | .28 | −0.01 | −0.40 | −0.27 | .28 | −0.03 | −0.95 | −0.38 | .28 | −.04 | −1.34 | −0.19 | .27 | −.02 | −0.70 |

| Sexual orientation (Heterosexual referent) | 1.43 | .31 | 0.12 | 4.62** | 1.42 | .31 | 0.12 | 4.63** | 1.38 | .31 | .12 | 4.52** | 1.12 | .29 | .10 | 3.86** |

| Race (white referent) | −1.48 | .33 | −0.13 | −4.53** | −1.31 | .33 | −0.12 | −3.99** | −1.28 | .33 | −.12 | −3.93 | −1.12 | .31 | −.10 | −3.63** |

| Ethnicity (hispanic referent) | −1.05 | .36 | −0.09 | −2.91** | −1.05 | .36 | −0.09 | −2.95** | −1.02 | .35 | −.08 | −2.87 | −0.87 | .34 | −.07 | −2.60** |

| Student Status (Non-student referent) | −0.69 | .34 | −0.06 | −2.02* | −0.65 | .34 | −0.06 | −1.93 | −0.55 | .33 | −.05 | −1.64 | −0.28 | .32 | −.03 | −0.87 |

| Employment status (full-time referent) | −0.08 | .35 | −0.01 | −0.23 | −0.07 | .34 | −0.01 | −0.22 | −0.12 | .34 | −.01 | −0.34 | 0.13 | .32 | −.01 | −0.39 |

| Education level (less than college referent) | 0.61 | .31 | 0.06 | 1.97* | 0.53 | .31 | 0.05 | 1.72 | 0.68 | .31 | .06 | 2.20* | 0.53 | .29 | .05 | 1.84 |

| Income | 0.02 | .01 | 0.08 | 2.17* | 0.02 | .01 | 0.08 | 2.27* | 0.02 | .01 | .08 | 2.40* | 0.02 | .01 | .09 | 2.69** |

| Marital status (single referent) | −0.71 | .37 | −0.06 | −1.90 | −0.73 | .37 | −0.06 | −2.00* | −0.65 | .37 | −.05 | −1.78 | −0.48 | .35 | −.04 | −1.37 |

| Relationship status (no relationship referent) | −0.27 | .32 | −0.02 | −0.84 | −0.28 | .32 | −0.02 | −0.89 | −0.18 | .32 | −.02 | −0.56 | −0.31 | .30 | −.03 | −1.05 |

| Size of social group | 0.29 | .10 | 0.08 | 2.94** | 0.29 | .10 | .07 | 2.96** | 0.21 | .09 | .06 | 2.27* | ||||

| Concern about group safety | 0.25 | .29 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 0.26 | .28 | .02 | 0.90 | 0.40 | .27 | .04 | 1.49 | ||||

| Someone takes responsibility for safety (Yes referent) | −0.50 | .32 | −0.04 | −1.56 | −0.44 | .32 | −.04 | −1.39 | −0.08 | .30 | −.01 | −0.27 | ||||

| Frequently drunk group member (no referent) | 1.45 | .24 | 0.16 | 6.02** | 1.42 | .24 | .16 | 5.93** | 1.19 | .23 | .13 | 5.26** | ||||

| Drug use | 1.32 | .32 | .11 | 4.18** | 1.07 | .30 | .09 | 3.59** | ||||||||

| Passenger | 3.88 | .32 | .36 | 12.32** | ||||||||||||

| Non-private transportation method | 4.71 | .45 | .31 | 10.51** | ||||||||||||

| R2 = .05 | R2 = .08, ΔR2 = .03, | R2 = .09, ΔR2 = .01, | R2 = .20, ΔR2 = .10, | |||||||||||||

| F(11,1399) = 6.52** | F(4,1395) = 8.36** | F(2,1394) = 9.02** | F(2,1392) = 18.73** | |||||||||||||

p < .05.

p < .01.

4. Discussion

Regardless of which BAC measure was used (entry, change in BAC at club, cumulative BAC at exit), alternate transportation patrons had the highest BAC levels, followed by passengers, then drivers. Although both passengers and alternate transportation users had much higher BACs than drivers, patrons using alternate methods of transportation consistently had a significantly higher mean BAC than either of the other two groups of patrons.

To be sure, patrons using alternate transportation typically do not belong behind the wheel of a car. In that respect, our data confirm the impact of the public health safety messages that have primarily emphasized the dangers of drinking and driving or riding with a drunk driver and have produced safer driver behavior in terms of alcohol (Voas, Johnson, & Miller, 2013). Encouragingly, drivers consistently had the lowest levels of BAC for all three measure. Though given the similar rates of apparent drug use between the three groups, messages about driving and drug use has yet to have the same effect.

However, these drinking and driving messages do not address the dangers of becoming intoxicated when alternate forms of transportation are used. This is not an inconsequential number of individuals. Our large metropolitan area with alternate transportation provides an environment conducive to supporting nightlife entertainment and findings are likely to generalize to other similar urban settings. Our data represent the behavior of single evenings and our measure of alternate transportation use was only for that same night (patrons may use different methods of transportation on different nights). In addition, the majority of participants (73%) have been patrons at clubs one or more times in the past month. Therefore there is a very concerning cumulative risk profile for those who use alternate transportation.

In particular, our evidence suggests that patrons using alternate transportation might make assumptions about their safety that are not accurate or are quite unconcerned about their safety. First, when assessing those who reported using alternate transportation, they had the highest percentage that could not identify a group member who takes responsibility (43.6%) and the lowest concern for the group's safety (39.1%). In addition, those choosing alternate methods of transportation had the highest percentage of individuals reporting having a frequently drunk member of their social drinking group (71.1%) for the night, a factor predictive of all BAC assessments regardless of transportation choice. These characteristics, combined with their significantly higher mean entrance BAC (“pre-loading”), give a profile of patrons engaged in high risk behavior together (clubbing with others who are likely to be intoxicated) who have no safety strategy and little or no concern for their safety in the club situation. Their risk behavior continues through the night with an increase in BAC such that they, on average, leave the club approaching legally intoxicated. This suggests that there is a need for public safety messages that target this vulnerable group of young adults who engage in a high risk evening for entertainment.

There are a number of different types of public health messages that may need to be communicated. Not driving does not protect one from all risks associated with a heavy drinking evening; other risks are still possible, including physical injuries or victimization. Risks associated with vulnerabilities for being targeted for physical and/or sexual assault, pedestrian accidents, and other adverse consequences are not addressed by the focus on drinking and driving. Creating new public health messages that raise awareness of these high risk outcomes are needed. Promoting public health safety to drinkers using alternate transportation methods may need a more complex and nuanced message. The message must not counter the established message of “don't drink and drive” but it must indicate that there are other risks for heavy drinking patrons who are not using cars for transportation.

Key messages appropriate for patrons who use alternate transportation might include increased knowledge of safe drinking levels and make use of the social drinking groups in which these patrons arrive at the clubs. For example, given the high levels of “pre-loading” that contributes to the high exit BACs, groups could develop a plan for limiting in-club drinking and watching for signs of acute intoxication. In addition, patrons who exit alone and drunk may be at increased risk for being a victim of theft or assault (Barton & Husk, 2012; Carpenter, 2005; Stitt & Giacopassi, 1992; Wells, Graham, Tremblay, & Magyarody, 2011). Certain sub-groups may be more vulnerable to violence and victimization if they leave the clubs intoxicated and unable to manage their safety upon exiting. Women may be more vulnerable to sexual predators as our evidence indicates that they are leaving clubs at the same levels of intoxication of young males (Miller et al., 2009). Group safety plans should be encouraged so that no individual group member is exiting the club alone and potentially intoxicated. In addition, patrons may also be vulnerable to being injured as a pedestrian on the streets. Alternate transportation that is available in the early evening hours may be less available during the late night hours, such as in San Francisco where subways are not available after 1:00 AM on weekends, while closing time for clubs is generally after 2:00 AM. Group members are a potential resource for securing safer forms of transportation, such as during times when public transportation may not be accessible.

4.1. Limitations

There are several caveats in considering the implications of our results. These findings are specific to club settings that offer EMDEs and are not necessarily relevant to other drinking establishments or live music events. Our data collection methods required the consent and cooperation of the clubs to establish a data collection site close to the venue entrance/exit. To the extent that the access to clubs is related to characteristics of the patrons limits the generalizability of findings. In addition, the sidewalk setting limited the number of questions that could be asked.

Highlights.

There are significant differences in blood alcohol concentration (BAC) between individuals who take different methods of transportation when leaving nightclubs.

After controlling for other potentially contributing factors (such as demographics, social drinking group characteristics, and drug use) transportation methods were consistently the strongest predictors of BAC.

The only other consistently strong predictor of BAC was having a frequently drunk member in the social drinking group.

All significant predictors in these analyses are factors that may be amenable to intervention.

References

- Administration, N. H. T. S. Traffic safety facts 2010 data: Alcohol-impaired driving. 2012 DOT HS 811 606. [Google Scholar]

- Barton A, Husk K. Controlling pre-loaders: Alcohol related violence in an English night time economy. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2012;12(2):89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Board, N. T. S. Reaching zero: Actions to eliminate alcohol-impaired driving Safety Report (NTSB/SR-13/01) Washington, DC: NTSB; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brower AM, Carroll L. Spatial and temporal aspects of alcohol-related crime in a college town. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55(5):267–275. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.5.267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CS. Heavy alcohol use and the commission of nuisance crime: Evidence from underage drunk driving laws. American Economic Review. 2005;95(2):267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright J, Asbridge M. Passengers decisions to ride with a driver under the influence of either alcohol or cannabis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(1):86–95. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill BD, Harding WM, Moore BA. DWI prevention: Profiles of drinkers who serve as designated drivers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(2):143–150. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill BD, Rogers JW, Howard J, Frissell KC, Harding WM. Avoiding DWI among bar-room drinkers: Strategies and predictors. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2010;4:35–51. doi: 10.4137/SART.S5414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditter SM, Elder RW, Shults RA, Sleet DA, Compton R, Nichols JL. Effectiveness of designated driver programs for reducing alcohol-impaired driving: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(5, Suppl):280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dultz LA, Frangos S, Foltin G, Marr M, Simon R, Bholat O, et al. Alcohol use by pedestrians who are struck by motor vehicles: How drinking influences behaviors, medical management, and outcomes. The Journal of Trauma. 2011;71(5):1252–1257. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182327c94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth AJM. Front, side, and back-loading: Patrons' rationales for consuming alcohol purchased off-premises before, during, or after attending nightclubs. Journal of Substance Use. 2010;15(1):31–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/14659890902966463. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Clapp JD, Dumas TM, Kelley-Baker T, Miller PG, et al. Street intercept method: An innovative approach to recruiting young adult high-risk drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014 doi: 10.1111/dar.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding WM, Caudill BD, Moore BA. Do companions of designated drivers drink excessively? Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13(4):505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CK, Owens EG. One for the road: Public transportation, alcohol consumption, and intoxicated driving. Journal of Public Economics. 2011;95(1–2):106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Clapp JD. Impact of providing drinkers with “know your limit” information on drinking and driving: A field experiment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:79–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Voas R, Miller B. Driving decisions when leaving electronic music dance events: Driver, passenger and group effects. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2012;13:577–584. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.678954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange JE, Reed MB, Johnson MB, Voas RB. The efficacy of experimental interventions designed to reduce drinking among designated drivers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):261–268. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Byrnes HF, Branner A, Johnson M, Voas R. Group influences on individuals' drinking and other drug use at clubs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(2):280–287. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Furr-Holden D, Johnson M, Holder H, Voas R, Keagy C. Biological markers of drug use in the club setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(2):261–268. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Relyea-Chew A, Wang J, Riley S, Boisvert D, Gomez T. Drinking behaviors in young adults: The potential role of designated driver and safe ride home programs. Injury Prevention. 2007;13(3):168–172. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.015032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryb GE, Dischinger PC, Kufera JA, Soderstrom CA. Social, behavioral and driving characteristics of injured pedestrians: A comparison with other unintentional trauma patients. Accident; Analysis and Prevention. 2007;39(2):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman N, Cinnamon J, Crooks VA, Hameed SM. Pedestrian injury and the built environment: An environmental scan of hotspots. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:233–233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt B, Giacopassi D. Alcohol availability and alcohol-related crime. Criminal Justice Review (CJR) 1992;17(2):268–279. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Erickson DJ, Carlin BP, Lenk KM, Quick HS, Jones AM, et al. The association between density of alcohol establishments and violent crime within urban neighborhoods. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(8):1468–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01753.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Erickson DJ, Carlin BP, Quick HS, Harwood EM, Lenk KM, et al. Is the density of alcohol establishments related to nonviolent crime? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(1):21–25. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Transportation, N. H. T. S. A. Statistical analysis of alcohol-related driving trends, 1982–2005 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Furr-Holden D, Lauer E, Bright K, Johnson MB, Miller B. Portal surveys of time-out drinking locations: A tool for studying binge drinking and AOD use. Evaluation Review. 2006;30(1):44–65. doi: 10.1177/0193841X05277285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Johnson MB, Miller BA. Alcohol and drug use among young adults driving to a drinking location. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;(0) doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wells S, Graham K, Tremblay PF, Magyarody N. Not just the booze talking: Trait aggression and hypermasculinity distinguish perpetrators from victims of male barroom aggression. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(4):613–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01375.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells BE, Kelly BC, Golub SA, Grov C, Parsons JT. Patterns of alcohol consumption and sexual behavior among young adults in nightclubs. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(1):39–45. doi: 10.3109/00952990903544836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]