Abstract

Uninfected female rats (Rattus novergicus) exhibit greater attraction to the males infected with protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. This phenomenon is contrary to the aversion towards infected males observed in multitude of other host–parasite associations. In this report, we describe a proximate mechanism for this anomaly. We demonstrate that T. gondii infection enhances hepatic production and urinary excretion of α2u-globulins in rats. We further demonstrate that α2u-globulins are sufficient to recapitulate male sexual attractiveness akin to effects of the infection. This manipulation possibly results in greater horizontal transmission of this parasite between the infected male and the uninfected female. It supports the notion that in some evolutionary niches parasites can alter host sexual signaling, likely leading to an increased rate of sexual transmission.

Upon infection, Toxoplasma gondii invades immune-privileged organs of male rats like brain and testes. Ensuing chronic infection causes change in the behavior of the infected rats, namely: (a) loss of aversion to cat odors (Berdoy et al., 2000; Vyas and Sapolsky, 2010) and (b) gain of enhanced sexual attractiveness (Dass et al., 2011; Vyas, 2013). These changes plausibly lead to greater transmission of the parasite by trophic route to the cat intestine and by sexual route to female rats, although incontrovertible evidence of greater transmission in field conditions is not yet available (Worth et al., 2013). Correlative suggestions have also been made about increased attractiveness of infected human males and sexual transmission in humans (Hodkova et al., 2007; Flegr et al., 2014), although definitive evidence is presently unavailable. The gain in attractiveness post infection is particularly interesting because parasitism is generally observed to reduce sexual attractiveness of the host across varied phylogenies (Hamilton and Zuk, 1982; Folstad and Karter, 1992; Kavaliers et al., 2005). In this report, we investigate the proximate mechanism of this paradoxical effect.

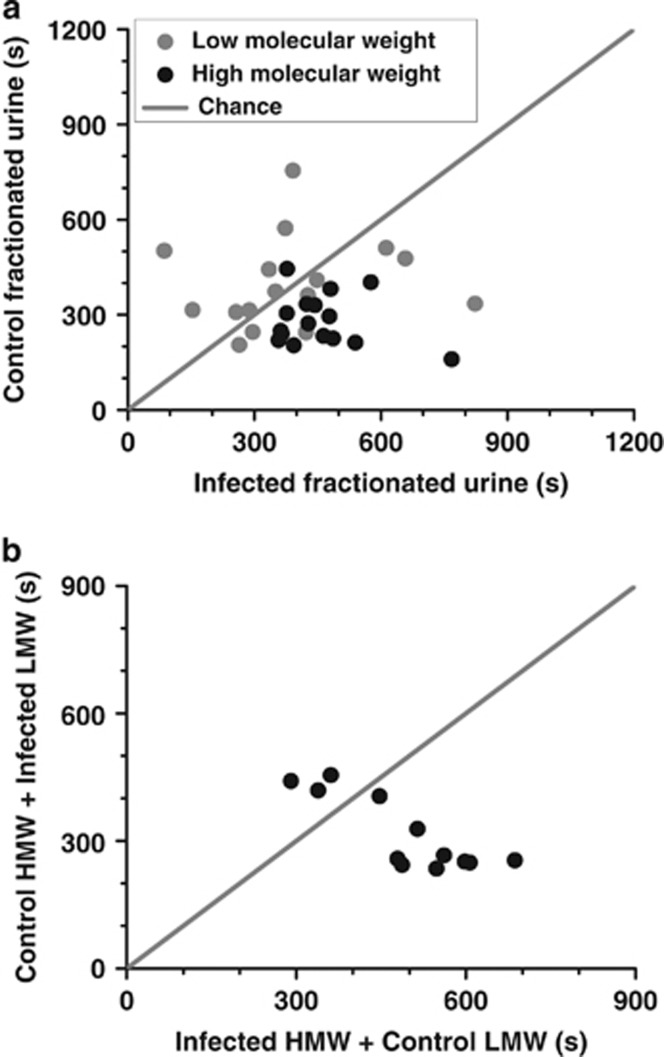

We first determined preference of uninfected estrus females for urine marks from control and infected males in an approach–approach conflict assay (detailed methods are described in Supplementary Information). Females spent greater time in bisect containing urine from the infected males (8/11 females, control < infected). For each second spent in the vicinity of urine from control males, receptive females spent 2.12 s with the infected male urine (paired t-test: |t10|=2.78, P=0.019). Subsequently, female preference for low- and high-molecular weight fractions of the urine was separately quantified (LMW and HMW, respectively; cutoff=3 kDa). Volatiles bound to HMW fraction were displaced by a competitive molecule, menadione (Papes et al., 2010). Volatiles in HMW fractions before and after menadione displacement were compared with vehicle using direct analysis in real-time mass spectrometry (DART-MS). This analysis indicated the absence of any bound volatiles in displaced samples used for behavioral measurements. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant interaction between infection status and the fractions (F(1,30)=8.23, P=0.007). Females exhibited comparable preference to the LMW fraction of control and infected males (Figure 1a; control: 387±47 s, infected: 398±35 s; paired t-test: |t15|=0.22, P>0.8; statistical power=0.054). In contrast, HMW fraction of the infected male was significantly preferred over that of control males (Figure 1a; control: 282±20 s, infected: 457±26 s; |t15|=4.84, P<0.001). HMW fraction of infected animals exhibited greater attractiveness even when grafted on control LMW fraction (Figure 1b; control: 317±25 s, infected: 493±34 s; |t11|=3.09, P=0.01). The majority of urinary proteins in the HMW fraction were determined to be α2u-globulins through mass spectrometric analysis (LOC259246 and LOC298109). Proteins homologous to rat α2u-globulins are also involved in chemical communication in mice (Hurst, 2009; Papes et al., 2010; Vasudevan and Vyas, 2013), including sexual signaling (Roberts et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

The greater attractiveness of T. gondii-infected males was communicated by HMW, and not LMW, fraction of the male urine. Estrus females exhibited greater attraction to HMW fraction of the urine obtained from the infected males (a, black dots). N=16 females. ANOVA: P=0.514 for fractions; P=0.018 for infection status; P=0.007 for interaction. Abscissa and ordinate depict time spent in bisect containing urine from infected or control animals, respectively (in second, trial duration=1200 s). Solid circles depict data obtained from individual females. Gray diagonal line depicts chance (abscissa=ordinate). The attraction was not recapitulated by LMW fraction (<3 kDa) of the urine (a, gray dots). HMW obtained from infected animals was attractive to females even when combined with LMW of control urine (b). N=12 females. Mass spectroscopic analysis revealed major component of HMW fraction to be α2u-globulins.

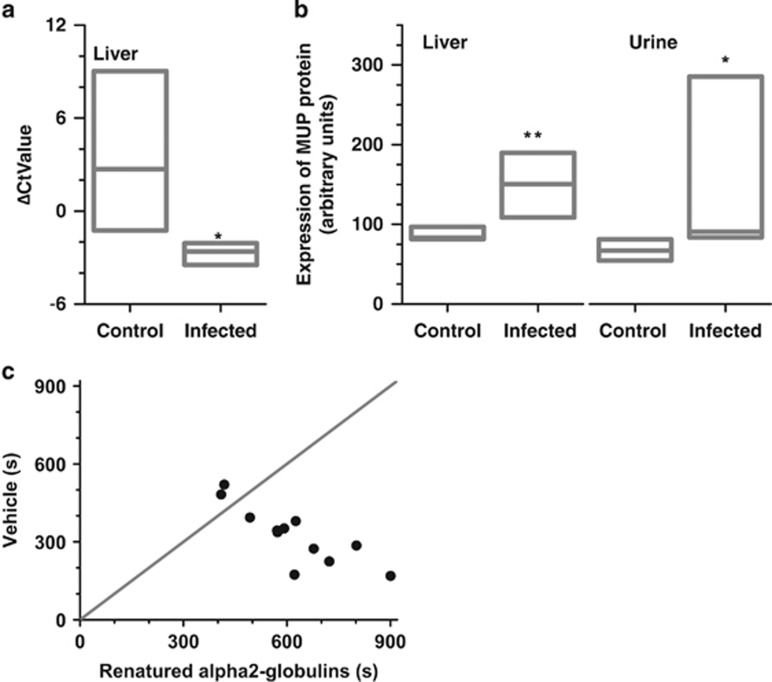

Infected animals contained greater amounts of α2u-globulin mRNA and protein in liver (Figures 2a and b). Congruently, urine from infected animals contained greater amounts of α2u-globulins (Figure 2b, 138% increase; P=0.011). In both liver and urine, the 25th percentile of α2u-globulin quantity in infected animals surpassed the 75th percentile of respective controls. α2u-globulins levels in preputial glands did not significantly differ between control and infected males (P=0.37).

Figure 2.

Toxoplasma gondii infection increased α2u-globulins production in liver and excretion in urine. Infection enhanced α2u-globulins mRNA abundance in the liver (a). Ordinate depicts PCR cycles needed to reach a threshold when using α2u-globulins primers minus when using GAPDH primers (a housekeeping gene). Box plot depicts median, 25th percentile and 75th percentile. *P<0.05; exact Mann–Whitney test. N =7. Liver and urine from infected animals contained greater amounts of α2u-globulin protein. N=6 control, 8 infected (liver); N=7 (urine) (b). Ordinate depicts densitometric intensity, normalized to intensity of a pooled sample run in the same gel. Same pooled samples were used in all gels of the experiment. Creatinine-adjusted urine samples were used. Both groups exhibited comparable filtration rates of urine from the kidney (creatinine content; P>0.9) and a comparable tendency to place urine marks in a novel arena (P>0.9). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01; exact Mann–Whitney test. N=7. Renatured α2u-globulins postdialysis were sufficient to recapitulate greater attractiveness (c). Females exhibited attraction to FPLC-purified HMW fraction containing α2u-globulins, even after its denaturation in 3 m guanidinium chloride, subsequent dialysis and then renaturation in buffered physiological saline to remove all bound volatiles. N=12 females.

Volatile substances in urine are known to bind α2u-globulins. The observation that HMW fraction from urine of infected animals was able to retain greater attractiveness even after menadione displacement supports the notion that α2u-globulins rather than volatiles bound to it were the active ingredients. We conducted a further experiment to test the possibility of residual volatiles still being bound to α2u-globulins in amounts undetectable by DART-MS. The fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC)-purified α2u-globulins fraction was denatured, dialyzed and transferred to physiological buffer for renaturation. Dialysis with excess buffer was used in an intervening part of the cycle to remove any residual volatiles. Renaturation was confirmed by circular dichroism and tryptophan imaging. This procedure failed to rescue female attractiveness. Females exhibited robust preference to dialyzed α2u-globulins (Figure 2c; 10/12 females; |t11|=4.09, P=0.002). Moreover, females exhibited clear preference for a greater concentration of FPLC-purified α2u-globulins in two-choice preference task comparing low and high doses (5 μg μl−1: 334±41 s, 1.66 μg μl−1: 208±24 s; paired t-test: |t10|=2.78, P=0.014). These observations suggest that α2u-globulins can signal attractiveness without necessity of volatiles and in a dose-dependent manner. This is consistent with ability of HMW urinary fraction from the infected animals to evoke greater attraction, coupled with greater production of α2u-globulins postinfection. In other words, T. gondii infection increases urinary excretion of α2u-globulins, and greater α2u-globulins in the infected urine is sufficient to signal greater attractiveness. Greater α2u-globulins production in the infected rats is congruent with the observations that these proteins require testosterone for synthesis and that T. gondii infection increases testosterone production in male rats (Kulkarni et al., 1985; Lim et al., 2013).

Many models of sexual selection posit that male sexual advertisement is an ‘honest' proxy of an ability to fight infections. This honesty is thought to arrive because resources used for sexual advertising produce a handicap in ability to fight parasites or pathogens (Hamilton and Zuk, 1982; Wingfield et al., 1997). In other words, sexual signals are expensive to produce or maintain, thus allowing only fit males to engage in the advertisement. Many parasites do exploit host sexual signals. More frequently, this exploitation takes the form of either eavesdropping on sexual signals to find a new host or to inter-species mimicry of sexual signals by parasites to attract a potential host (Zuk and Kolluru, 1998; Haynes and Yeargan, 1999; Zuk et al., 2006). Parasites in these cases do not influence host advertisement per se. In this backdrop, rat–T. gondii association provides additional plausibility of the parasites changing magnitude of host sexual advertisement.

Parasites are known to affect the behavior of their hosts (Hughes et al., 2012). This observation is frequently employed to argue that natural selection acts on genes and not necessarily individuals. In this narrative, the body of the host becomes an extended phenotype of the parasite (Dawkins, 1999; Hunter, 2009) and the behavioral changes correlate with increased transmission of the parasite. T. gondii has earlier been shown to increase sexual attractiveness of the infected males, resulting in greater sexual transmission of the parasite (Dass et al., 2011). Current observations present a molecular mechanism for T. gondii-induced extended phenotype.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Ministry of Education (AV) and National Research Foundation (JYY), Singapore. We thank Oliver Martin Mueller Cajar, Surajit Bhattacharyya and Sebanti Gupta for technical help.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Berdoy M, Webster JP, Macdonald DW. Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:1591–1594. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dass SA, Vasudevan A, Dutta D, Soh LJ, Sapolsky RM, Vyas A. Protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii manipulates mate choice in rats by enhancing attractiveness of males. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins R. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford University Press: New York, USA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Flegr J, Klapilova K, Kankova S. Toxoplasmosis can be a sexually transmitted infection with serious clinical consequences. Not all routes of infection are created equal. Med Hypotheses. 2014;83:286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstad I, Karter AJ. Parasites, bright males, and the immunocompetence handicap. Am Nat. 1992;139:603–622. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WD, Zuk M. Heritable true fitness and bright birds: a role for parasites. Science. 1982;218:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.7123238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes KF, Yeargan KV. Exploitation of Intraspecific Communication Systems: Illicit Signalers and Receivers. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1999;92:960–970. [Google Scholar]

- Hodkova H, Kolbekova P, Skallova A, Lindova J, Flegr J. Higher perceived dominance in Toxoplasma infected men—a new evidence for role of increased level of testosterone in toxoplasmosis-associated changes in human behavior. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2007;28:110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DP, Brodeur J, Thomas F. Host Manipulation by Parasites. Oxford University Press: UK; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter P. Extended phenotype redux. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:212–215. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst JL. Female recognition and assessment of males through scent. Behav Brain Res. 2009;200:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaliers M, Choleris E, Pfaff DW. Genes, odours and the recognition of parasitized individuals by rodents. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AB, Gubits RM, Feigelson P. Developmental and hormonal regulation of alpha 2u-globulin gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2579–2582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A, Kumar V, Hari Dass SA, Vyas A. Toxoplasma gondii infection enhances testicular steroidogenesis in rats. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:102–110. doi: 10.1111/mec.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papes F, Logan DW, Stowers L. The vomeronasal organ mediates interspecies defensive behaviors through detection of protein pheromone homologs. Cell. 2010;141:692–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SA, Simpson DM, Armstrong SD, Davidson AJ, Robertson DH, McLean L, et al. Darcin: a male pheromone that stimulates female memory and sexual attraction to an individual male's odour. BMC Biol. 2010;8:75. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan A, Vyas A. Kairomonal communication in mice is concentration-dependent with a proportional discrimination threshold. F1000Res. 2013;2:195. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-195.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Sapolsky R. Manipulation of host behaviour by Toxoplasma gondii: what is the minimum a proposed proximate mechanism should explain. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 2010;57:88–94. doi: 10.14411/fp.2010.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A. Parasite-augmented mate choice and reduction in innate fear in rats infected by Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:120–126. doi: 10.1242/jeb.072983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield JC, Jacobs J, Hillgarth N. Ecological constraints and the evolution of hormone-behavior interrelationships. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;807:22–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth AR, Lymbery AJ, Thompson R. Adaptive host manipulation by Toxoplasma gondii: fact or fiction. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk M, Kolluru GR. Exploitation of sexual signals by predators and parasitoids. Q Rev Biol. 1998;73:415–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zuk M, Rotenberry JT, Tinghitella RM. Silent night: adaptive disappearance of a sexual signal in a parasitized population of field crickets. Biol Lett. 2006;2:521–524. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.