Abstract

Background

The majority of cases with severe pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) are caused by auto-antibodies against GM-CSF. A multitude of genetic and exogenous causes are responsible for few other cases. Goal of this study was to determine the prevalence of GATA2 deficiency in children and adults with PAP and hematologic disorders.

Methods

Of 21 patients with GM-CSF-autoantibody negative PAP, 13 had no other organ involvement and 8 had some form of hematologic disorder. The latter were sequenced for GATA2.

Results

Age at start of PAP ranged from 0.3 to 64 years, 4 patients were children. In half of the subjects GATA2-sequence variations were found, two of which were considered disease causing. Those two patients had the typical phenotype of GATA2 deficiency, one of whom additionally showed a previously undescribed feature – a cholesterol pneumonia. Hematologic disorders included chronic myeloic leukemia, juvenile myelo-monocytic leukemia, lymphoblastic leukemia, sideroblastic anemia and two cases of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). A 4 year old child with MDS and DiGeorge Syndrome Type 2 was rescued with repetitive whole lung lavages and her PAP was cured with heterologous stem cell transplant.

Conclusions

In children and adults with severe GM-CSF negative PAP a close cooperation between pneumologists and hemato-oncologists is needed to diagnose the underlying diseases, some of which are caused by mutations of transcription factor GATA2. Treatment with whole lung lavages as well as stem cell transplant may be successful.

Background

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a rare disorder characterized by the progressive accumulation of surfactant in the alveoli of the lungs, leading to hypoxemic respiratory failure and, in severe cases, to death [1]. PAP is caused by (i) genetic diseases which result in dysfunction of surfactant or surfactant production (SFTPC, SFTPB, ABCA3, TTF1 deficiency) mainly presenting during infancy, by (ii) disruption of GM-CSF signaling from mutations in the receptor (GM-CSFRa, GM-CSFRb) or from acquired autoantibodies against GM-CSF, and by (iii) disorders that presumably impair surfactant clearance because of abnormal numbers or defective phagocytic functions of alveolar macrophages [2]. The latter are caused by inhaled particles or by hematologic disorders affecting macrophage precursors.

A broad spectrum of hematologic disorders have been associated with PAP, most frequently myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and more rarely acute (AML) and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), myelofibrosis, acute lymphoid leukaemia (ALL), adult T-cell leukaemia, aplastic anemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, essential thrombocytosis [3], congenital dyserythropoietic anemia [4], and status after unrelated stem cell transplant [5, 6]. Up to now only mutations in one specific gene -GATA2- have been associated with this form of PAP.

GATA2 is a zinc finger transcription factor essential for differentiation of immature hematopoietic cells [7]. Among many other functions GATA2 regulates the phagocytosis of alveolar macrophages [8]. Alveolar macrophages treated with the sense GATA-2 expression construct show an increase in their phagocytic activity by up to 280 % compared to the antisense construct [9]. GATA2 deficiency is a recently described disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity, caused by heterozygous mutations leading to haplo-insufficiency of the transcription factor GATA2. The disease presents with a complex array of diagnoses and symptoms of varying extent including MDS, AML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), severe viral, disseminated mycobacterial and invasive fungal infections, pulmonary arterial hypertension, warts, panniculitis, human papillomavirus (HPV) positive tumors, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive tumors, venous thrombosis, lymphedema, sensorineural hearing loss, miscarriage and hypothyroidism [6]. PAP has been reported in about 18 % of all subjects with GATA2 deficiency [6, 10]. However, not much is known on the severity and clinical course of PAP in these subjects, which were exclusively adults. Pneumologists treating patients with severe PAP not caused by autoantibodies against GM-CSF frequently do not know the cause of these rare conditions [11].

Here, we investigate a cohort of children and adults with severe and chronic PAP and hematologic disease for the presence of GATA2 mutations. GATA2 mutations were identified in a minority of patients only. One child with a GATA2 variant was successfully treated initially by therapeutic whole lung lavages (WLL) and eventually by stem cell transplant.

Methods

All subjects with PAP diagnosed based on the characteristic phenotype by lung biopsy or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and CT scan findings were identified from the kids-lung-register (http://www.kinderlungenregister.de/index.php/en/) within the child-EU project (European Register and Biobank on Childhood Interstitial Lung Diseases, European Commission, FP7, GA 305653).

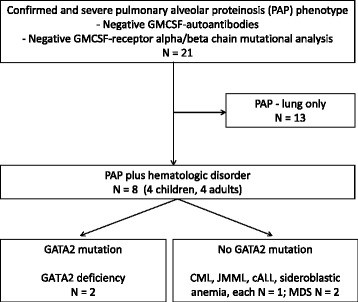

In order to differentiate subgroups of PAP, all patients with GM-CSF-Ra or Rb mutations [12] and a high GM-CSF autoantibody level were excluded. 21 subjects were identified of whom 13 (11 adults, 2 children) had pulmonary involvement only. 8 subjects suffered from PAP and a hematologic disease - diagnosed by standard procedures- and were selected for further analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design and flow of subjects retrieved from the kids-lung-register data base and biobank. Abbreviations: PAP, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis; CML, chronic myeloic leukemia, JMML, juvenile myelo-monocytic leukemia; cALL, common acute lymphoblastic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome

The GATA2 gene was analysed by Sanger sequencing. Genomic DNA was isolated from EDTA blood samples using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) and PCR amplified using HotStarTaq polymerase (Qiagen). PCR products were purified with the MinElute 96 UF PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). Primers used for PCR and sequencing reactions are shown in Table 1. Sequencing was performed by GATC Biotech AG (Konstanz, Germany).

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for amplification of the GATA2 gene

| Exon | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | CCC GCA AAG TGA TGT CG | CAA ACG GAC CAA GCG ATT C |

| #2 | ACC TCG TGG TGG GAC TTT G | GAT CCT ACA TCC GGG AAG C |

| #3/1 | GTC CCT AGC TCT GCC TAC CC | CTC CTC GGG CTG CAC TAC |

| #3/2 | ACC TTT TCG GCT TCC CAC | CTC TCC CAA GTC ACA GCT CC |

| #4 | GAC TCC CTC CCG AGA ACT TG | TGT AAT TAA CCG CCA GCT CC |

| #5 | GTG GAG CGA GGG TCA GG | CAC AAA GCG CAG AGG TCC |

| #6/1 | AGG AAT GTT GCT GGA GGA AG | AAC TGT CCA TGC AGG AAA CC |

| #6/2 | GAC ACC ACT CCT GCC AGC | ACA CAG TCA CAG CAG CTT CG |

| #6/3 | TGG AGG GCA GAG ACA ATC AC | AGC AGG GAC ACA GCC TCT C |

| #6/4 | CTT TGC TGC CCT TGG TTT C | AAT CTG GCT GCC CAA ATT C |

In subject 4 800 ng of genomic DNA extracted from formalin fixed tissue were fragmented to an average size of 200 bp and desired fragment sizes were obtained with Agencourt® AMPure® XP beads (Beckman Coulter). Sequencing libraries were prepared using Accel-NGS-1S Library Kit (Swift Biosciences, Ann Harbor, MI), sequenced on the HiSeq 1500 (Illumina) and aligned to the human genome assembly (hg19). The GATA2 locus was covered by 86 reads.

Follow-up data of the patients were collected until October 2014. The study was approved by the institutional review board, the ethics commission of the medical faculty of the Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany (EK 026–06). All parents or guardians gave their written informed consent, the children gave assent.

Results

Age at onset of PAP ranged from 0.4 to 64 years. Half of the patients were children (Table 2). Beside chronic respiratory insufficiency due to PAP, all patients suffered from recurrent respiratory tract infections or exacerbations. These were mainly common cold viral infections, in some cases non-tuberculous mycobacteria, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were identified. All patients were immunodeficient: in three patients primary immunodeficiency syndromes were identified: two with a monocyte deficiency not further specified (no. 2, 4) and one with a Di George type II syndrome with combined immunodeficiency (no. 7); all three patients are described below in detail. In the other patients, immunodeficiency was secondary to the hematologic condition (CML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), c-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (cALL), MDS) and/or therapeutic interventions (steroids, immunosuppressant medication).

Table 2.

Clinical detail of the patients with hematologic PAP

| No | Sex | Start pulm. dis. (y) | Course pulm. dis. | Chest CT scan | Treatments | Age at last follow up (y) | Out-come | Final diagnosis and likely cause of PAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 64 | Chronic respiratory insufficiency, PAP, inactive TBC, ARDS | Diffuse ground glass with clear interstitial septal thickening (crazy paving pattern), bilateral alveolar consolidations | Oxygen, WLL (2) | 66 | dead | CML, karyotype 46XX t(9,22) (q34,q11) 25, CD 2+, renal failure |

| 2 | M | 34 | Respiratory insufficiency, recurrent interstitial pneumonia (HSV); bron-chiolitis obliterans; PAP | Interstitial thickening and destructions in both lungs, crazy-paving pattern | Prednisolone, azathioprine, oxygen, WLL (3) | 37 | dead | Monocyte defect, M. avium intracellulare infection, GATA2 mutation (p.Y377D) |

| 3 | M | 0.6 | Infection, tachydyspnea (7 months old), hypoxia, PAP (1.7 y) | Diffuse ground glass, interstitial markings, emphysema | Oxygen, immune-suppressive drugs, methylprednisolone, WLL (3) | 3, lost on follow up | sick-same | Juvenile myelo-monocytic leukemia, Monosomy 7, 2x SCT, intestinal, hepatic, cutaneous GVHD |

| 4 | F | 38 | Dyspnea, clubbing, respiratory insufficiency, cholesterol pneumonia, PAP | Diffuse ground glass, interstitial markings, scattered alveolar opacities | Oxygen, no WLL | 43, lost on follow up | sick-same | Monocyte defect, cholesterol pneumonia, GATA2 mutation (p.R398W) |

| 5 | F | 6 | PAP | Ground glass, interstitial pneumonia | Oxygen, no WLL | 7 | sick-better | C-acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| 6 | F | 59 | Dyspnea, respiratory insufficiency, PAP | Diffuse ground glass, interstitial septal thickening (crazy paving), markedly basal, with traction bronchiectasis | Oxygen, WLL (1) | 59 | dead | MDS |

| 7 | F | 4 | Recurrent airway infections; chronic hypoxic failure, PAP | Alveolar opacities in almost all lung areas, see Fig. 2 | Oxygen, WLL (14) | 7.3 | healthy | MDS, DiGeorge Syndrome Type 2, Monosomy 7, Trisomy 8 (SCT) |

| 8 | M | 0.33 | CMV infection, respiratory failure, PAP | Ground glass opacities with interstitial septal thickening (crazy paving pattern), alveolar consolidations bilaterally in the lower parts | Oxygen, WLL (11) | 2 | sick-better | Sideroblastic anemia |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; dis., disease; GVHD, graft versus host disease; HSV, herpes simplex virus; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; PAP, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis; pulm., pulmonary; SCT, stem cell transplant; TB, tuberculosis, WLL, whole lung lavage; y, years; number in (), number of WLL

The hallmark of all patients of this study was severe PAP with continuous need of oxygen (Table 2). All but two subjects (no. 4, 5) were treated symptomatically with repetitive therapeutic WLL to improve respiratory insufficiency. Treatment was eventually not successful in 3 patients who died from respiratory failure, complicated by infection or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Autoantibodies against GM-CSF were determined in order to characterize PAP further, they were negative in all patients (Table 3). Serum levels of GM-CSF were not significantly increased in the patients with serum available. 4 of the 8 patients had sequence anomalies in GATA2 (Table 3). Two of these, a synonymous variant and a missense variant were predicted not to be damaging by Polyphen-2 [13] and SIFT [14]. The other two were heterozygous point mutations predicted to be deleterious, both of these patients had a phenotype characteristic for GATA2 deficiency.

Table 3.

Laboratory results of the patients with hematologic PAP

| No | ID | GM-CSF auto-anti-bodies in serum | GM-CSF in plasma [pg/mL] (normal 5.5 ± 7.2)a | GATA2-gene analysis | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 153 | Negative | n.a. | c.564 G > C ht; p.T188T | Synonymous variant; C-allele frequency of 0.09 |

| 2 | 163 | Negative | 5 | c.1129 T > G ht; p.Y377D | Missense mutation, deleterious |

| 3 | 194 | Negative | n.a. | Normal | |

| 4 | 432 | Negative | 2.9 | c.1192C > T ht;p.R398W | Missense mutation, deleterious |

| 5 | 1505 | Negative | 0.0 | Normal | |

| 6 | 1740 | Negative | 17.5 | Normal | |

| 7 | 2334 | Negative | 11.5 | c.490 G > A ht; p.A164T | Missense variant; tolerated, minor allele frequency of 0.24 |

| 8 | 2530 | Negative | 1.8 | Normal |

Abbreviations: n.a. not available

aCarraway et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161: 1294–1299

The courses of cases 2, 4, 7 and 8 are reported in more detail to illustrate characteristic presentations.

Case no. 2

A 34 year old male patient presented with disseminated Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection, including the lungs, chronic labial herpes including a positive serum HSV PCR, and M. Bowen of the skin. Cellular immunodeficiency was suspected based on absent monocytes; the patient was HIV-negative. 3 years later the patient developed respiratory insufficiency, the CT scan showed consolidations suspicious of cryptogenic organizing or atypical pneumonia. Several courses of antibiotic therapy were followed by two pulses of cyclophosphamide; the patient deteriorated further, CT scan showed bilateral interstitial thickening and crazy-paving pattern. Open lung biopsy revealed PAP. Bone marrow aspiration was normal. He was treated symptomatically with WLL under ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) support, developed anuric acute renal failure, and died from acute cardiac failure. The patient carried the mutation p.Y377D in the GATA2 gene.

Case no. 4

A 38 year old female patient presented with recurrent bronchitis and sinusitis, breathlessness during exercise, and interstitial markings on chest x-ray. An open lung biopsy was performed, histology revealed PAP associated with cholesterol pneumonia. Liver and bone marrow biopsies were normal. In the following months she developed progressive peripheral edema and cardiac insufficiency with mild pulmonary hypertension. She further developed a pseudomembranous glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome and a Pseudomonas urosepsis at 39 years. At 40 years cellular immunodeficiency was demonstrated based on the absence of monocytes. She developed condylomatous lesions of the vulva and HPV-associated (types 16 and 28) vulva intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2–3 (VIN2-VIN3), which was resected. Her course was determined by chronic respiratory failure (at rest 4LO2/min; PaO2 45 mmHg (normal > 86), normal PaC02). However, no WLL were performed as the patient was lost on follow up at 43 years. The patient carried the mutation p.R398W in the GATA2 gene.

Case no. 7

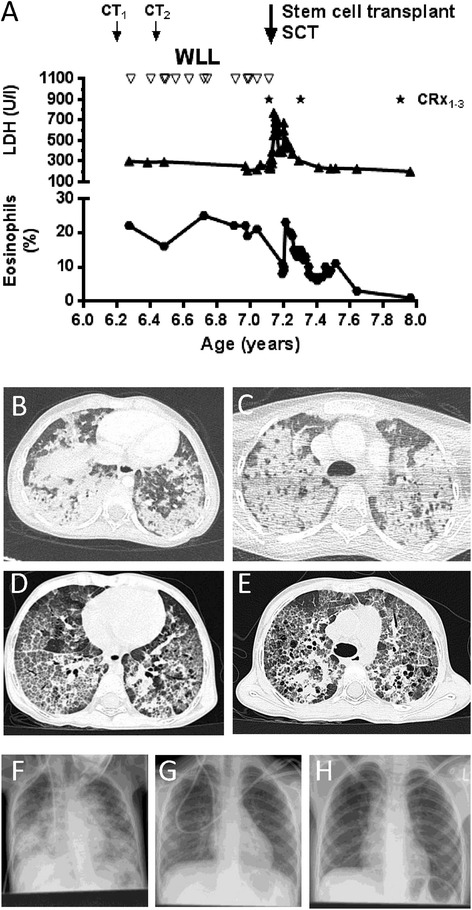

A 4.5 year old girl with Di George Syndrome type II from deletion of 10p (OMIM 601362) with severe immunodeficiency, single right kidney, inner ear deafness, mild cognitive delay and dystrophy (BMI 12.0 kg/m2 < 1. percentile)), presented with weight loss, dry cough and frequent night awakenings due to acute dyspnea. The condition deteriorated slowly. She had to sleep in an up-right position when she was referred to our hospital at the age of 6 years. Her oxygen saturation was 75 % without and 92 % with 6 L of O2/min. She had silent breath sounds and a reduced white blood cell count with eosinophilia (1050/μl: neutrophils 8 %, lymphocytes 67 %, monocytes 4 %, eosinophils 19 %, basophils 1 %). MDS with refractory cytopenia (MDS-RC), cytogenetic abnormalities (del 10p, trisomy 8, monosomy 7) and secondary PAP was diagnosed. In BAL fluid elevated eosinophils and granular eosinophilic debris, PAS +, characteristic for PAP were seen. She was treated with 14 WLL by pulmonary artery catheter technique [15], with good clinical and radiological response over a period of one year (Fig. 2). A HLA-identical (10/10) unrelated-stem cell donor was identified at the age of 10 years and she received allogeneic stem cell transplant. Within a few weeks after transplant, PAP and respiratory distress resolved (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Long term course of a child suffering from DiGeorge syndrome type II and PAP due to MDS with monosomy 7, trisomy 8, and a GATA2 missense variant. Successful treatment by therapeutic WLLs, and definitive treatment of the PAP by SCT. (a) clinical course (b,c) CT1 at presentation (d,e) CT2 after first 2 whole lung lavages (f) CXR 1 before SCT (g) CXR2 7 weeks after SCT and (h) CXR3 1 year after SCT

Case no. 8

A full-term boy with normocytic anemia (Hb 13.1 g/dL) presented after a few weeks with paleness, fatigue, tachydyspnea, and failure to thrive. At the age of four month the hemoglobin level had decreased to 5.3 g/dL and a sideroblastic anemia was diagnosed. No genetic cause was identified; Pearson syndrome and mutations in ALAS2 and SLC25A38 were excluded. His bone marrow showed massive erythroid hyperplasia with dyserythropoiesis and marked depression of myeloid cells. Pulmonary infiltrates were initially interpreted as pneumonia. At the age of 5 months a CMV infection was successfully treated with ganciclovir. At 8 months he developed respiratory failure (PaO2 60 mmHg, PaCO2 55 mmHg) with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. The diagnosis of PAP was made by analysis of BAL fluid and open lung biopsy. From the age 8 to 23 months the boy underwent 11 therapeutic WLLs, improving his general condition and gas exchange. Currently he maintains oxygen-saturation levels above 92 % under oxygen support 0.5-1 l of O2/min). The anemia is stable with Hb levels between 7.5 and 9.0 g/dL. The molecular cause of very rare sideroblastic anemia was not revealed, the associated depression of myeloid cells was likely the cause of PAP. GATA2 deficiency was not causal, as the patient showed no GATA2 variant in our investigations; potential intronic variations were not investigated.

Discussion

This study shows that GATA2 mutations in patients with hematologic diseases and severe PAP occur at a relatively low frequency. GATA2 analysis may help to diagnose the underlying hematologic condition. Severe PAP in children due to MDS can be cured by stem cell transplant.

Severe PAP is a rare but serious complication of hematologic disorders. Here we differentiated two groups of diseases having in common a presentation with significant chronic respiratory insufficiency and recurrent pulmonary tract infections or exacerbations. These groups included (i) patients with GATA2 deficiency, a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity [6], and (ii) patients with functionally or numerically reduced alveolar macrophages and/or their respective mononuclear precursors due to CML, JMML, cALL, MDS or sideroblastic anemia in the absence of disease causing GATA2 mutations.

GATA2 deficiency has a broad phenotype encompassing immunodeficiency, MDS/AML, pulmonary disease, and vascular/lymphatic dysfunction. A precise history and knowledge of the disease course may help to select potential candidates with high confidence for specific genetic diagnostic. GATA2 gene mutations were associated with PAP in two cases; p.Y377D is a novel missense mutation demonstrated here to present with the classical monoMAC syndrome [16]. p.R398W has previously been described in six patients, of whom 2 had a PAP [6]. Here we add the histopathological feature of cholesterol pneumonia to this phenotype. Of interest, further heterozygous variations in GATA2 were identified in two other subjects; however these were predicted to be non-disease causing (Table 3). As not all subjects with a specific GATA2 mutation causing GATA2 deficiency develop PAP [6], additional factors are involved which determine PAP. Patients with the same GATA2 mutation need to be investigated further and experimental models will help to better understand the molecular defect(s) leading to PAP. Similarly, in non-GATA2 deficient patients with PAP and hematologic abnormalities, the mechanism of PAP development is unknown. Currently, their PAP is presumed to be due to reduced monophagocytic function in the alveoli to clear surfactant [17]. Best proof for the critical role of bone-marrow derived alveolar macrophages for surfactant homeostasis is provided by the correction of PAP by SCT. This was shown here for the first time in a young child. Shortly, i.e. within days after take of SCT, there was clearing of PAP, superseding rapidly the need for therapeutic WLLs (Fig. 1).

Here we also show that WLLs are feasible also for children, even at very young age, with small sized airways and in the presence of severe respiratory distress, using techniques we have established previously [18]. WLL can be used to symptomatically treat all types of PAP and to bridge until the underlying condition can be cured or alternative treatments have been implemented.

Due to relative immune deficiency state and irrespective of the cause, the impact of infections should be considered carefully. It is likely that with often severe respiratory tract infections PAP may be triggered to deteriorate. Thus we recommend early diagnosis and proper antimicrobial treatment, in particular of organisms characteristic for these often lethal conditions, including mycobacteria, nocardia, herpes viruses, and fungi [6, 19, 20]. In addition and concordant with the immune deficiency the extensive usage of systemic corticosteroids should be cautioned, as there is so far no evidence of their beneficial effect in PAP. Extensive usage might enhance immune deficiency and weaken antimicrobial defense further [15].

After confirming the diagnosis of PAP either by a combination of characteristic CT scan and BAL findings and trans-bronchial or open lung biopsy, it is important to determine the etiology of PAP. As more than 90 % of PAP in adulthood is caused by autoantibodies against GM-CSF [1, 21, 22], this condition has to be initially excluded by analysis of serum [23, 24]. None of our patients had increased levels of GM-CSF autoantibodies. Serum levels of GM-CSF are low in autoimmune PAP [25], whereas elevated values can be found in congenital GM-CSFRa or GM-CSFRb defects and possibly in other forms of PAP. Thus, particularly in children these other entities need to be excluded. In our cohort of patients with severe PAP and hematologic diseases, serum GM-CSF level were low to intermediate, supporting some up regulation of GM-CSF. Next, genetic analysis of GATA2 is helpful in order to diagnose the underlying hematologic entity more precisely, in particular in patients who meet the broad but characteristic phenotype of GATA2 deficiency [6]. This diagnostic algorithm for PAP will allow differentiating important subgroups and may help to identify further genetic abnormalities, known or suspected to be associated with PAP.

Conclusions

When investigating a patient with severe PAP, the pneumologist should be aware of the wide range of diseases which can cause secondary PAP and consider interdisciplinary involvement of a hemato-oncologist. Conversely, hemato-oncologists should include PAP in the differential diagnosis of respiratory failure associated with pulmonary interstitial changes in hematologic diseases.

Acknowledgements

The work of MG was kindly supported by Else-Kroener-Fresenius Stiftung (MG 2013_A72), by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (EuPAPNet project inside ERARE, number 01GM1011A), European Register and Biobank on Childhood Interstitial Lung Diseases (European Commission, FP7, GA 305653, chILD-EU).

Abbreviations

- ABCA3

ATB-binding cassette sub-family A member 3

- ALL

Acute lymphoid leukemia

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- cALL

common acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CML

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- CMML

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HPV

Human papilloma virus

- HSV

Herpes simplex virus

- JMML

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- PAP

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- SFTPB

Gene encoding for Surfactant protein B

- SFTBC

Gene encoding for Surfactant protein C

- TTF1

Thyroid transcription factor 1

- WLL

Whole lung lavage

Footnotes

Maurizio Luisetti is deceased

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MG designed the study, collected the cases, analysed the data and wrote the draft of the manuscript. He is the guarantor of the entire manuscript. UC, AMH, JL, KK, BF, ML, CS, CK and MG contributed and evaluated patients and performed chart review, ZR, AS, BH, SK, CKr, and JA performed laboratory analyses, CU, CKr and BF critically revised the manuscript, DT provided tissue samples and performed histopathological analyses, AS, TW, UC and FB contributed to the long term collection of subjects, patient recruitment and evaluation. All contributors read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Author’s information

This paper is devoted to Prof. Maurizio Luisetti’s outstanding contribution to the field of human alveolar proteinosis.

Contributor Information

Matthias Griese, Email: matthias.griese@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Ralf Zarbock, Email: ralf.zarbock@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Ulrich Costabel, Email: ulrich.costabel@ruhrlandklinik.uk-essen.de.

Jenna Hildebrandt, Email: jenna.hildebrandt@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Dirk Theegarten, Email: Dirk.Theegarten@uk-essen.de.

Michael Albert, Email: michael.albert@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Antonia Thiel, Email: antonia.thiel@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Andrea Schams, Email: andrea.schams@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Joanna Lange, Email: joanna_lange@wp.pl.

Katazyrna Krenke, Email: katarzynakrenke@gmail.com.

Traudl Wesselak, Email: traudl.wesselak@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Carola Schön, Email: Carola.Schoen@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Matthias Kappler, Email: matthias.kappler@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Helmut Blum, Email: blum@lmb.uni-muenchen.de.

Stefan Krebs, Email: krebs-st@lmb.uni-muenchen.de.

Andreas Jung, Email: andreas.jung@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Carolin Kröner, Email: carolin.kroener@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Christoph Klein, Email: christoph.klein@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Ilaria Campo, Email: i.campo@smatteo.pv.it.

Maurizio Luisetti, Email: i.campo@smatteo.pv.it.

Francesco Bonella, Email: Francesco.Bonella@ruhrlandklinik.uk-essen.de.

References

- 1.Seymour JF, Presneill JJ. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: progress in the first 44 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(2):215–235. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo I, Kadija Z, Mariani F, Paracchini E, Rodi G, Mojoli F, Braschi A, Luisetti M. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Multidisciplinary Respir Med. 2012;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishii H, Seymour JF, Tazawa R, Inoue Y, Uchida N, Nishida A, Kogure Y, Saraya T, Tomii K, Takada T, et al. Secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis complicating myelodysplastic syndrome results in worsening of prognosis: a retrospective cohort study in Japan. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carden MA, Barman A, Massey G. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in association with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia: a case report. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:624740. doi: 10.1155/2012/624740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari M, Rougemont AL, Le Deist F, Ozsahin H, Duval M, Champagne MA, Fournet JC. Secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis after unrelated cord blood hematopoietic cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16(5):E146–E149. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinner MA, Sanchez LA, Hsu AP, Shaw PA, Zerbe CS, Calvo KR, Arthur DC, Gu W, Gould CM, Brewer CC, et al. GATA2 deficiency: a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity. Blood. 2014;123(6):809–821. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresnick EH, Katsumura KR, Lee HY, Johnson KD, Perkins AS. Master regulatory GATA transcription factors: mechanistic principles and emerging links to hematologic malignancies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(13):5819–5831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang X, Lasbury ME, Davidson DD, Bartlett MS, Smith JW, Lee CH. Down-regulation of GATA-2 transcription during Pneumocystis carinii infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68(8):4720–4724. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.8.4720-4724.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lasbury ME, Tang X, Durant PJ, Lee CH. Effect of transcription factor GATA-2 on phagocytic activity of alveolar macrophages from Pneumocystis carinii-infected hosts. Infect Immun. 2003;71(9):4943–4952. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4943-4952.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu AP, Sampaio EP, Khan J, Calvo KR, Lemieux JE, Patel SY, Frucht DM, Vinh DC, Auth RD, Freeman AF, et al. Mutations in GATA2 are associated with the autosomal dominant and sporadic monocytopenia and mycobacterial infection (MonoMAC) syndrome. Blood. 2011;118(10):2653–2655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-356352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaulagain CP, Pilichowska M, Brinckerhoff L, Tabba M, Erban JK. Secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in hematologic malignancies. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2014;7(4):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildebrandt J, Yalcin E, Bresser HG, Cinel G, Gappa M, Haghighi A, Kiper N, Khalilzadeh S, Reiter K, Sayer J, et al. Characterization of CSF2RA mutation related juvenile pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griese M, Ripper J, Sibbersen A, Lohse P, Brasch F, Schams A, Pamir A, Schaub B, Muensterer OJ, et al. Long-term follow-up and treatment of congenital alveolar proteinosis. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camargo JF, Lobo SA, Hsu AP, Zerbe CS, Wormser GP, Holland SM. MonoMAC syndrome in a patient with a GATA2 mutation: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(5):697–699. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey B, Trapnell BC. The molecular basis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Immunol. 2010;135(2):223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiter K, Schoen C, Griese M, Nicolai T. Whole-lung lavage in infants and children with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20(12):1118–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazenwadel J, Secker GA, Liu YJ, Rosenfeld JA, Wildin RS, Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Hsu AP, Dyack S, Fernandez CV, Chong CE, et al. Loss-of-function germline GATA2 mutations in patients with MDS/AML or MonoMAC syndrome and primary lymphedema reveal a key role for GATA2 in the lymphatic vasculature. Blood. 2012;119(5):1283–1291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu AP, Johnson KD, Falcone EL, Sanalkumar R, Sanchez L, Hickstein DD, Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Lemieux JE, Zerbe CS, Bresnick EH, et al. GATA2 haploinsufficiency caused by mutations in a conserved intronic element leads to MonoMAC syndrome. Blood. 2013;121(19):3830–3837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonella F, Bauer PC, Griese M, Wessendorf TE, Guzman J, Costabel U. Wash-out kinetics and efficacy of a modified lavage technique for alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(6):1468–1474. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00017612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonella F, Bauer PC, Griese M, Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: new insights from a single-center cohort of 70 patients. Respir Med. 2011;105(12):1908–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latzin P, Tredano M, Wust Y, de Blic J, Nicolai T, Bewig B, Stanzel F, Kohler D, Bahuau M, Griese M. Anti-GM-CSF antibodies in paediatric pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Thorax. 2005;60(1):39–44. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.021329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue Y, Nakata K, Arai T, Tazawa R, Hamano E, Nukiwa T, Kudo K, Keicho N, Hizawa N, Yamaguchi E, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Japan. Respirology. 2006;11(Suppl):S55–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchida K, Nakata K, Suzuki T, Luisetti M, Watanabe M, Koch DE, Stevens CA, Beck DC, Denson LA, Carey BC, et al. Granulocyte/macrophage-colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies and myeloid cell immune functions in healthy subjects. Blood. 2009;113(11):2547–2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]