Abstract

O6-methylguanine-methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status has prognostic and, in the subpopulation of elderly patients, predictive value in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Therefore, knowledge of the MGMT promoter methylation status is important for clinical decision-making. So far, MGMT testing has been limited by the lack of a robust test with sufficiently high analytical performance. Recently, one of several available pyrosequencing protocols has been shown to be an accurate and robust method for MGMT testing in an intra- and interlaboratory ring trial. However, some uncertainties remain with regard to methodological issues, cut-off definitions, and optimal use in the clinical setting. In this article, we highlight and discuss several of these open questions. The main unresolved issues are the definition of the most relevant CpG sites to analyze for clinical purposes and the determination of a cut-off value for dichotomization of quantitative MGMT pyrosequencing results into “MGMT methylated” and “MGMT unmethylated” patient subgroups as a basis for further treatment decisions.

Keywords: glioblastoma, management, prognosis, MGMT promoter methylation, pyrosequencing

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common primary brain tumor with inherently poor prognosis [1]. The current standard of treatment for glioblastoma patients aged 18 – 65 years is maximal safe resection of the tumor with subsequent radiotherapy and concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide-based alkylating chemotherapy (TMZ) [2]. Evidence from two randomized clinical trials supports stratification of therapy according to the methylation status of the O6-methylguanine-methyltransferase MGMT gene promoter in the population of elderly glioblastoma patients (> 65 years in the NOA-08 study and > 60 years in the Nordic Glioma study) [3, 4]. In these clinical trials, patients with an unmethylated MGMT promoter benefit more from radiotherapy alone, while patients with a methylated MGMT promoter benefit more from temozolomide chemotherapy alone. However, it must be noted that the interpretation of the true predictive value of the MGMT promoter methylation status has been limited in both trials, as the analytical performance of the assay was not investigated and MGMT test results were available in only a fraction of cases (56% in the NOA-08 study and 59% in the Nordic Glioma Study, respectively). In non-elderly glioblastoma patients, MGMT promoter methylation status does not fulfil the criteria of a predictive factor and does not directly guide therapeutic decisions, but it is a strong prognostic factor, which impacts clinical management [5]. For these reasons, MGMT testing is increasingly requested in the clinical setting and is recommended for routine clinical decision-making in elderly patients by current guidelines [6]. However, it remains unclear, which test method is most suitable for clinical MGMT testing, as several assays lack the necessary analytical performance (reproducibility and repeatability).

Several recent studies show that MGMT pyrosequencing is a robust technique that offers valid, reliable and quick evaluation of the MGMT promoter methylation status from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded glioblastoma specimens and is therefore a rational candidate method for clinical purposes [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. However, some uncertainties remain with regard to methodological issues, cut-off definitions, and optimal use of MGMT pyrosequencing in the clinical setting. This article aims at highlighting and discussing several of these open questions.

Methods

Methods of literature review

The search for papers within the PubMed database was performed using the terms: “MGMT pyrosequencing” (76 results), “MGMT methylation glioma” (613 results), “MGMT methylation glioblastoma” (482 results), last performed on June 10, 2015. In this review we included only studies in which tissue samples of human glioblastoma were analyzed by MGMT pyrosequencing.

Open questions and unresolved issues

Which CpG sites should be analyzed?

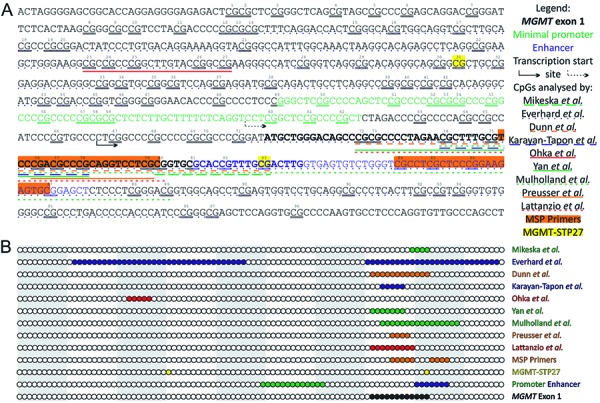

The MGMT promoter contains 98 individual CpG sites surrounding the transcription start site and comprises 2 differentially methylated regions (CpGs 25 – 50 and 73 – 90) (Figure 1) [34]. Due to the heterogeneous methylation of different CpG sites and the fact that most of the available methods for MGMT testing allow for the analysis of several sites, their proper selection seems crucial. Functional analyses showed that CpG 84 – 87 and 89 have the greatest impact on MGMT protein expression and co-localize with the minimal enhancer region (+143 to +201; containing binding sites for several transcription factors, including STAT3) [34, 35]. On the other hand, the analysis of CpGs 12 – 46 and 71 – 97 in glioblastoma patients showed that the methylation status of sites 27, 32, 73, 75, 79, 80 as well as means of 32 – 33 and 73 – 81 correlate best with the MGMT protein expression levels [9].

Figure 1. A: The annotated chromosome 10 sequence (positions: 129,466,653 – 129,467,461, gene build 19) with the MGMT CpG island (positions: 129,466,685 – 129,467,446) and short flanking sequences as well as a graphical legend. CpG sites within the island are marked with consecutive numbers and double underline. MGMT exon 1 is marked with bold. Minimal promoter and enhancer sequences (according to Harris et al. [35, 48]) are marked with green and blue, respectively. Transcription start sites are marked with solid arrow (according to gene build 19) and with dashed arrow (according to Harris et al. [48]). CpG sites analyzed in each publication are marked with a solid/dashed line underlining the sequence (the first author of the first paper analyzing given region is listed). MSP primers for the methylated sequence (according to Esteller et al. [49]) are marked with orange background. Two CpG sites included in the MGMT-STP27 model (based on HM-27K and HM-450K BeadChip arrays, according to Bady et al. [36]) are marked with yellow background. B: A simplified graphical representation of the MGMT CpG island with a circle representing each CpG site; alternating grey-white background marks decades of CpG sites. The sites belonging to each set are colored as above and explained in the legend on the right-hand side.

The methylation of the most commonly studied region, encompassing CpGs 74 – 78, was shown to significantly affect the prognosis for the patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma [10, 12, 18, 19, 20, 22]. This region was described as relatively homogeneously methylated by Felsberg et al. [13], while as highly heterogeneous in some cases by Quillien et al. [20]. Nonetheless, the variation in the prognostic significance of different sites was relatively low [10, 12, 18, 20].

The mean methylation of the region containing CpGs 74 – 89 has shown significant correlation with survival of glioblastoma patients in three studies [21, 26, 27]. The observed methylation profile was often heterogeneous and, based on the optimal (outcome-wise) cut-off values, the closest correlation with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) was observed for CpGs 84, 89 as well as means 84 – 88, 74 – 78, and 76 – 80 according to the study by Quillien et al. [26], and for CpGs 85 and 87 according to the study by Collins et al. [27].

Additionally, the regions containing CpGs 23 – 27 [14, 15], 72 – 78 [17, 33], 72 – 80 [29], 72 – 83 [8, 28], 76 – 79 [25, 31], and 80 – 83 [7] were also analyzed, but the biological or clinical relevance of individual sites were not assessed. The prognostic significance was tested for CpGs 23 – 27 [14], 72 – 78 [33], 72 – 80 [29], and 72 – 83 [8, 28], and was proven for CpGs 72 – 80 [29], and 72 – 83 [8, 28]. The methylation of CpGs 23 – 27 and 80 – 83 was congruent with protein activity [15] and bisulfite sequencing [7], respectively.

Finally, selecting more than one site for identification of the methylation status raises the issue whether all have the same biological or clinical relevance or not. The first scenario simply uses the mean of methylation levels for each site (as in most studies [8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 32, 32, 33]), the second one relies on a weighted approach (e.g., based on logistic regression as proposed for pyrosequencing by Mikeska et al. [7] or as MGMT-STP27, consisting of CpG 31 and 84, model for HM-450K and HM-27K BeadChip by Bady et al. [36]).

In summary, there is a high heterogeneity among the studies in terms of the region analyzed, however, almost all of them focused on the region comprising exon 1 and enhancer (Figure 1). So far, best evidence exists for CpGs 74 – 78, as it is the best studied region, however, promising results have also been obtained with the analysis of larger regions (CpGs 72 – 83 and 74 – 89) and the distal part of the CGI (CpGs 84 – 89). Nonetheless, none of these analyses has been an adequately powered, prospective study. Thus, it remains unclear at the moment which region of the MGMT gene promoter is optimal for clinical decision-making. This question can only be resolved by further studies that aim at elaborating which CpG sites show the most relevant influence on patient outcome parameters.

Current use of MGMT status in clinical decision-making

MGMT pyrosequencing yields a quantitative result, i.e., the percentage of methylated alleles for each of the investigated CpG sites. Some studies indicate that the continuous assay read-out carries prognostically relevant information, as higher methylation levels positively correlated with favourable patient survival times (Table 1). On note, application of a cut-off threshold to distinguish two patient groups (“MGMT methylated” and “MGMT unmethylated” patients) may lead to loss of clinically relevant information. As a consequence, in patients in whom treatment stratification is not dependent on MGMT promoter methylation status, i.e., the non-elderly patient population, continuous information on the percentage of methylated CpG sites in the MGMT promoter could be of interest for accurate prognostication of patient survival times. However, in patients in whom the MGMT status indeed is used to make treatment decisions, a distinct cut-off value is needed. At the moment this situation is given in the elderly population in whom the decision to recommend either radiotherapy (MGMT unmethylated or inconclusive test result) or chemotherapy (MGMT methylated) depends on the MGMT promoter methylation status.

Table 1. Summary of all publications in which the MGMT promoter methylation was analyzed by pyrosequencing in human glioblastoma tissue. The data include: the number of glioblastoma samples analyzed by pyrosequencing and the fixation method, study type (whether prospective or retrospective and whether a clinical trial with homogeneous therapy or not), analyzed region (as the consecutive CpG numbers within the MGMT CpG island), applied threshold (all values listed if samples were divided into more than 2 groups; if different threshold values were used for the various sites, the range is shown in parentheses).

| Samples | Material | Study type | CpGs | Threshold | Prognostic | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Frozen | Retrospective | 80 – 83 | 10% | N/A | [7] |

| 109 | Frozen, FFPE | Retrospective | 72 – 83 | 9%, 29% | Yes | [8] |

| 54 | Frozen | Retrospective | 12 – 46; 71 – 97 | 9%, 29% | N/A | [9] |

| 81 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 8% | Yes | [10] |

| 17 | FFPE | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | N/A | No | [11] |

| 51 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 10%, 27% | Yes | [12] |

| 48 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 8% | N/A | [13] |

| 54 | Frozen | Retrospective | 23 – 27 | 14% | No | [14] |

| 41 | Frozen | Retrospective | 23 – 27 | N/A | N/A | [15] |

| 15 | FFPE | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 9%, 29% | N/A | [16] |

| 77 | Frozen | Retrospective | 72 – 77 | 10% | N/A | [17] |

| 41 | FFPE | Prospective clinical trial | 74 – 78 | 10% (11 – 45%) | Yes | [18] |

| 86 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 2.68% | Yes | [19] |

| 100 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 8% | Yes | [20] |

| 182 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 89 | 10% | Yes | [21] |

| 166 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 8%, 25% | Yes | [22] |

| 78 | FFPE | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 8% | Yes | [23] |

| 64 | Frozen, FFPE | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 5.72%, 20%, 35% | No | [24] |

| 9 | Frozen, FFPE, RCLPE | Retrospective | 76 – 79 | 8% | N/A | [25] |

| 89 + 50 | Frozen | Retrospective | 74 – 89 | (4 – 32%) | Yes | [26] |

| 225 | FFPE | Prospective | 74 – 89 | 10% | Yes | [27] |

| 128 | Frozen | Retrospective | 72 – 83 | 10% | Yes | [28] |

| 46 | Frozen, FFPE | Retrospective | 72 – 80 | 9% | Yes | [29] |

| 43 | FFPE | Retrospective | 74 – 89 | 10% | N/A | [30] |

| 99 | FFPE | Retrospective | 76 – 79 | 8% | N/A | [31] |

| 303 | FFPE | Retrospective | 74 – 78 | 9% | Yes | [32] |

| 105 | Frozen | Retrospective | 72 – 77 | 10% | No | [33] |

It is important to note, however, that data on the optimal predictive cut-off value to distinguish elderly glioblastoma patients likely to benefit from radiotherapy or chemotherapy are not available, so far. Such data would need to be generated from analyses of tissue specimens collected within adequately powered and randomized prospective clinical trials. In such trials, an interaction between therapy and MGMT promoter methylation status as assessed by pyrosequencing could be determined for overall survival. Of note, in the NOA-08 and the Nordic Glioma study, statistically significant interactions between therapy and MGMT status were not reported for patient overall survival [3, 4]. However, both studies used methylation-specific PCR for quantification of MGMT promoter methylation and the used cut-off is not transferable to pyrosequencing. The available studies applying MGMT pyrosequencing to glioblastoma patients were mostly retrospective in nature and included heterogeneously treated patients and were, thus, not adequately designed to determine MGMT methylation threshold levels for predictive purposes [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. These studies used varying cut-off levels and some found a correlation of MGMT status with patient survival times with “MGMT methylated” patients generally having more favorable outcomes than “MGMT unmethylated” patients (Table 1). Although these studies suggest a prognostic role of MGMT promoter methylation status, they do not allow recommendations on a specific predictive cut-off value to distinguish “MGMT methylated” from “MGMT unmethylated” patients.

In addition to MGMT, there are other (bio-)markers where optimal predictive cut-points would have to be determined – (biological) age, Karnofsky index/WHO performance status, and radiation dosage [3, 4]. Thereby mutual dependences between these cut-points could exist; e.g., for patients between 60 and 70 years another MGMT cut-point could be optimal to decide between radiotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy than for patients > 70 years. Instead of hyping currently available cut-points and thereby pretending detailed knowledge, which actually does not exist yet, the definition of grey areas seems worth considering. They constitute biomarker intervals within which the decision for either of the two therapy options is appropriate; clear and well-founded therapy recommendations only exist for the extremes.

Studying MGMT is not over yet

The published pyrosequencing protocols used for testing of MGMT promoter methylation status in glioblastoma are variable and differ especially with regard to the number and position of the tested CpG sites. A ring trial has shown high intra- and interlaboratory reproducibility for a commercially available MGMT pyrosequencing kit, whereas the analytical performance of other MGMT pyrosequencing protocols in glioblastoma is unclear [25].

MGMT promoter methylation status as determined by pyrosequencing seems to correlate with the survival prognosis of glioblastoma patients. However, so far available studies are limited by their retrospective nature, heterogeneity in patient populations, heterogeneity in pyrosequencing protocols (tested CpG sites), and the low patient numbers. Overall, MGMT promoter methylation status as determined by pyrosequencing seems to be a prognostic biomarker in glioblastoma patients, although the current level of scientific evidence is low.

The predictive value of MGMT promoter methylation status as determined by pyrosequencing has not been addressed so far in systematic studies. The use of MGMT promoter methylation status as determined by pyrosequencing as predictive biomarker, e.g., for treatment decisions in elderly glioblastoma patients, is based on only weak and indirect scientific evidence, based on extrapolation of data elaborated with other methods of MGMT testing.

For predictive biomarker studies the same evidence standards have to be applied as for adopting new therapies. Hence, these studies will usually be prospectively designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Note that for logistic or ethical reasons, in particular in rare diseases, the retrospective use of data from already performed RCTs would also be possible. Various specific prospective study designs for predictive biomarker studies have been suggested [37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]; some with specific emphasis on determining predictive cut-points for continuously measured biomarkers [44, 45, 46].

Efficacy is the proof that a new treatment has sufficient therapeutic effect and is, among other things, necessary for marketing authorization decisions of regulatory bodies. Effectiveness is the treatment benefit in daily clinical routine when – among other things – no overly restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria are in effect; it is assessed by comparative effectiveness research studies [47]. The scientific evaluation of predictive biomarkers like MGMT should focus on (1) efficacy, (2) effectiveness, and (3) the clarification of any major gaps between them; thereby (2) and (3) constitute key tasks of medical research in academic institutions.

Summary and conclusions

MGMT pyrosequencing in glioblastoma has been shown to yield reproducible results within and between different laboratories

MGMT pyrosequencing yields the percentage of methylated alleles for each of the investigated CpG sites as quantitative result

The relative clinical relevance of the methylation status of individual CpG sites in the MGMT gene promoter is unclear and therefore open questions remain with regard to technical MGMT pyrosequencing assay setup, e.g., the selection of optimal PCR primers

The available data from retrospective studies support a prognostic value of MGMT pyrosequencing results with higher percentages of methylated CpG sites in the MGMT gene promoter correlating with favorable survival times.

A predictive cut-off value of MGMT pyrosequencing results for distinguishing MGMT methylated from MGMT unmethylated patients as a basis for treatment decisions has not yet been determined in adequately designed studies

Further studies should aim to identify and validate an optimal MGMT pyrosequencing assay not only with high analytical performance, but also with proven clinical performance. Of particular relevance is the identification and validation of reasonable cut-off levels for the use as predictive biomarker, e.g., for treatment decisions in elderly glioblastoma patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

M.B. is supported by the Healthy Ageing Research Centre project (REGPOT-2012-2013-1, 7FP). Special thanks to Prof. Thomas Ströbel, Institute of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, for helpful comments.

References

- 1. Louis D Ohgaki H Wiestler O Cavenee W World Health Organization classification of tumours of the central nervous system. IARC, Lyon: 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stupp R Mason WP van den Bent MJ Weller M Fisher B Taphoorn MJB Belanger K Brandes AA Marosi C Bogdahn U Curschmann J Janzer RC Ludwin SK Gorlia T Allgeier A Lacombe D Cairncross JG Eisenhauer E Mirimanoff RO; Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wick W Platten M Meisner C Felsberg J Tabatabai G Simon M Nikkhah G Papsdorf K Steinbach JP Sabel M Combs SE Vesper J Braun C Meixensberger J Ketter R Mayer-Steinacker R Reifenberger G Weller M Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13: 707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Malmstrӧm A Grønberg BH Marosi C Stupp R Frappaz D Schultz H Abacioglu U Tavelin B Lhermitte B Hegi ME Rosell J Henriksson R Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13: 916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berghoff AS Preusser M Clinical neuropathology practice guide 06-2012: MGMT testing in elderly glioblastoma patients – yes, but how? Clin Neuropathol. 2012; 31: 405–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weller M van den Bent M Hopkins K Tonn JC Stupp R Falini A Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal E Frappaz D Henriksson R Balana C Chinot O Ram Z Reifenberger G Soffietti R Wick W EANO guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of anaplastic gliomas and glioblastoma. Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15: e395–e403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mikeska T Bock C El-Maarri O Hübner A Ehrentraut D Schramm J Felsberg J Kahl P Büttner R Pietsch T Waha A Optimization of quantitative MGMT promoter methylation analysis using pyrosequencing and combined bisulfite restriction analysis. J Mol Diagn. 2007; 9: 368–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dunn J Baborie A Alam F Joyce K Moxham M Sibson R Crooks D Husband D Shenoy A Brodbelt A Wong H Liloglou T Haylock B Walker C Extent of MGMT promoter methylation correlates with outcome in glioblastomas given temozolomide and radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2009; 101: 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Everhard S Tost J El Abdalaoui H Crinière E Busato F Marie Y Gut IG Sanson M Mokhtari K Laigle-Donadey F Hoang-Xuan K Delattre JY Thillet J Identification of regions correlating MGMT promoter methylation and gene expression in glioblastomas. Neuro-oncol. 2009; 11: 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karayan-Tapon L Quillien V Guilhot J Wager M Fromont G Saikali S Etcheverry A Hamlat A Loussouarn D Campion L Campone M Vallette FM Gratas-Rabbia-Ré C Prognostic value of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase status in glioblastoma patients, assessed by five different methods. J Neurooncol. 2010; 97: 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stockhammer F Misch M Koch A Czabanka M Plotkin M Blechschmidt C Tuettenberg J Vajkoczy P Continuous low-dose temozolomide and celecoxib in recurrent glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2010; 100: 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uno M Oba-Shinjo SM Camargo AA Moura RP Aguiar PH Cabrera HN Begnami M Rosemberg S Teixeira MJ Marie SKN Correlation of MGMT promoter methylation status with gene and protein expression levels in glioblastoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011; 66: 1747–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Felsberg J Thon N Eigenbrod S Hentschel B Sabel MC Westphal M Schackert G Kreth FW Pietsch T Löffler M Weller M Reifenberger G Tonn JC Promoter methylation and expression of MGMT and the DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 in paired primary and recurrent glioblastomas. Int J Cancer. 2011; 129: 659–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohka F Natsume A Motomura K Kishida Y Kondo Y Abe T Nakasu Y Namba H Wakai K Fukui T Momota H Iwami K Kinjo S Ito M Fujii M Wakabayashi T The global DNA methylation surrogate LINE-1 methylation is correlated with MGMT promoter methylation and is a better prognostic factor for glioma. PLoS ONE. 2011; 6: e23332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kishida Y Natsume A Toda H Toi Y Motomura K Koyama H Matsuda K Nakayama O Sato M Suzuki M Kondo Y Wakabayashi T Correlation between quantified promoter methylation and enzymatic activity of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in glioblastomas. Tumour Biol. 2012; 33: 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tuononen K Tynninen O Sarhadi VK Tyybäkinoja A Lindlöf M Antikainen M Näpänkangas J Hirvonen A Mäenpää H Paetau A Knuutila S The hypermethylation of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene promoter in gliomas – correlation with array comparative genome hybridization results and IDH1 mutation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012; 51: 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yan W Zhang W You G Bao Z Wang Y Liu Y Kang C You Y Wang L Jiang T Correlation of IDH1 mutation with clinicopathologic factors and prognosis in primary glioblastoma: a report of 118 patients from China. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7: e30339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Christians A Hartmann C Benner A Meyer J von Deimling A Weller M Wick W Weiler M Prognostic value of three different methods of MGMT promoter methylation analysis in a prospective trial on newly diagnosed glioblastoma. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7: e33449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Håvik AB Brandal P Honne H Dahlback H-SS Scheie D Hektoen M Meling TR Helseth E Heim S Lothe RA Lind GE MGMT promoter methylation in gliomas-assessment by pyrosequencing and quantitative methylation-specific PCR. J Transl Med. 2012; 10: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quillien V Lavenu A Karayan-Tapon L Carpentier C Labussière M Lesimple T Chinot O Wager M Honnorat J Saikali S Fina F Sanson M Figarella-Branger D Comparative assessment of 5 methods (methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction, MethyLight, pyrosequencing, methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting, and immunohistochemistry) to analyze O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltranferase in a series of 100 glioblastoma patients. Cancer. 2012; 118: 4201–4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mulholland S Pearson DM Hamoudi RA Malley DS Smith CM Weaver JMJ Jones DTW Kocialkowski S Bäcklund LM Collins VP Ichimura K MGMT CpG island is invariably methylated in adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial tumors with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations. Int J Cancer. 2012; 131: 1104–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reifenberger G Hentschel B Felsberg J Schackert G Simon M Schnell O Westphal M Wick W Pietsch T Loeffler M Weller M Predictive impact of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma of the elderly. Int J Cancer. 2012; 131: 1342–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McDonald KL Rapkins RW Olivier J Zhao L Nozue K Lu D Tiwari S Kuroiwa-Trzmielina J Brewer J Wheeler HR Hitchins MP The T genotype of the MGMT C>T (rs16906252) enhancer single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is associated with promoter methylation and longer survival in glioblastoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2013; 49: 360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oberstadt MC Bien-Möller S Weitmann K Herzog S Hentschel K Rimmbach C Vogelgesang S Balz E Fink M Michael H Zeden JP Bruckmüller H Werk AN Cascorbi I Hoffmann W Rosskopf D Schroeder HW Kroemer HK Epigenetic modulation of the drug resistance genes MGMT, ABCB1 and ABCG2 in glioblastoma multiforme. BMC Cancer. 2013; 13: 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Preusser M Berghoff AS Manzl C Filipits M Weinhäusel A Pulverer W Dieckmann K Widhalm G Wöhrer A Knosp E Marosi C Hainfellner JA Clinical Neuropathology practice news 1-2014: pyrosequencing meets clinical and analytical performance criteria for routine testing of MGMT promoter methylation status in glioblastoma. Clin Neuropathol. 2014; 33: 6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quillien V Lavenu A Sanson M Legrain M Dubus P Karayan-Tapon L Mosser J Ichimura K Figarella-Branger D Outcome-based determination of optimal pyrosequencing assay for MGMT methylation detection in glioblastoma patients. J Neurooncol. 2014; 116: 487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Collins VP Ichimura K Di Y Pearson D Chan R Thompson LC Gabe R Brada M Stenning SP Prognostic and predictive markers in recurrent high grade glioma; results from the BR12 randomised trial. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014; 2: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shen D Liu T Lin Q Lu X Wang Q Lin F Mao W MGMT promoter methylation correlates with an overall survival benefit in Chinese high-grade glioblastoma patients treated with radiotherapy and alkylating agent-based chemotherapy: a single-institution study. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9: e107558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lattanzio L Borgognone M Mocellini C Giordano F Favata E Fasano G Vivenza D Monteverde M Tonissi F Ghiglia A Fillini C Bernucci C Merlano M Lo Nigro C MGMT promoter methylation and glioblastoma: a comparison of analytical methods and of tumor specimens. Int J Biol Markers. 2015; 30: e208–e216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xie H Tubbs R Yang B Detection of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma using pyrosequencing. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015; 8: 636–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu C-Y Ho H-L Lin S-C Chang-Chien Y-C Chen M-H Hsu SP-C Yen Y-S Guo W-Y Ho DM-T Prognosis of glioblastoma with faint MGMT methylation-specific PCR product. J Neurooncol. 2015; 122: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rapkins RW Wang F Nguyen HN Cloughesy TF Lai A Ha W Nowak AK Hitchins MP McDonald KL The MGMT promoter SNP rs16906252 is a risk factor for MGMT methylation in glioblastoma and is predictive of response to temozolomide. Neuro-oncol. 2015; epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cai J Zhang W Yang P Wang Y Li M Zhang C Wang Z Hu H Liu Y Li Q Wen J Sun B Wang X Jiang T Jiang C Identification of a 6-cytokine prognostic signature in patients with primary glioblastoma harboring M2 microglia/macrophage phenotype relevance. 2015; 10: e0126022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malley DS Hamoudi RA Kocialkowski S Pearson DM Collins VP Ichimura K A distinct region of the MGMT CpG island critical for transcriptional regulation is preferentially methylated in glioblastoma cells and xenografts. Acta Neuropathol. 2011; 121: 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harris LC Remack JS Brent TP Identification of a 59 bp enhancer located at the first exon/intron boundary of the human O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994; 22: 4614–4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bady P Sciuscio D Diserens A-C Bloch J van den Bent MJ Marosi C Dietrich P-Y Weller M Mariani L Heppner FL Mcdonald DR Lacombe D Stupp R Delorenzi M Hegi ME MGMT methylation analysis of glioblastoma on the Infinium methylation BeadChip identifies two distinct CpG regions associated with gene silencing and outcome, yielding a prediction model for comparisons across datasets, tumor grades, and CIMP-status. Acta Neuropathol. 2012; 124: 547–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mandrekar SJ Sargent DJ Predictive biomarker validation in practice: lessons from real trials. Clin Trials. 2010; 7: 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mandrekar SJ Sargent DJ Clinical trial designs for predictive biomarker validation: theoretical considerations and practical challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27: 4027–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mandrekar SJ Sargent DJ Clinical trial designs for predictive biomarker validation: one size does not fit all. J Biopharm Stat. 2009; 19: 530–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sargent DJ Conley BA Allegra C Collette L Clinical trial designs for predictive marker validation in cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23: 2020–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Galanis E Wu W Sarkaria J Chang SM Colman H Sargent D Reardon DA Incorporation of biomarker assessment in novel clinical trial designs: personalizing brain tumor treatments. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011; 13: 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Freidlin B Korn EL Biomarker enrichment strategies: matching trial design to biomarker credentials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014; 11: 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gosho M Nagashima K Sato Y Study designs and statistical analyses for biomarker research. Sensors (Basel). 2012; 12: 8966–8986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jiang W Freidlin B Simon R Biomarker-adaptive threshold design: a procedure for evaluating treatment with possible biomarker-defined subset effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99: 1036–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baker SG Kramer BS Sargent DJ Bonetti M Biomarkers, subgroup evaluation, and clinical trial design. Discov Med. 2012; 13: 187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. He P Identifying cut points for biomarker defined subset effects in clinical trials with survival endpoints. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014; 38: 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sargent D What constitutes reasonable evidence of efficacy and effectiveness to guide oncology treatment decisions? Oncologist. 2010; 15: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harris LC Potter PM Tano K Shiota S Mitra S Brent TP Characterization of the promoter region of the human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991; 19: 6163–6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Esteller M Hamilton SR Burger PC Baylin SB Herman JG Inactivation of the DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation is a common event in primary human neoplasia. Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]