Abstract

Background:

Under nutrition is a health problem in developing countries and the main aim of this study was determine of the nutritional status and some sociodemographic factors among rural under-5-year children in the North of Iran in 2013.

Methods:

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study, which carried out on 2530 children (637 = Fars-native, 1002 = Turkman and 891 = Sistani) from 21 villages in the North of Iran. Villages were chosen by random sampling among 118, and all of under-five children were chosen by simple sampling. For all of cases, a questionnaire with contain questions on the socialdemographic condition was completed and anthropometric indexes were measured by a learned team. Anthropometric data were compared with those in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference population. SPSS 18.0 software was used for statistical data analysis and P value under 0.05 included significations.

Results:

Generally, under nutrition (Z-score ≤ −2) was observed in 6.6%, 18.5% and 3.3% based on underweight, stunting and wasting, respectively and there were in boys more than girls and in Sistani more than other ethnic groups. Based on underweight and stunting, under nutrition was seen in Sistani more than other ethnic groups. Among three ethnic groups, stunting was significant both in boys (P = 0.013) and in girls (P = 0.004), but wasting was significant only in girls (P = 0.001). The estimated odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval of under nutrition was obtained from logistic regression. Compared with good economic group, the OR was 1.831 in poor economic groups (P = 0.001). The risk of under nutrition in Sistanish ethnic group was 1.754 times more than Fars-native group (P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

Under nutrition is a health problem among under-5-year children in rural area in the North of Iran and stunting was seen in an alarming rate among them. Among ethnic groups, Sistanish children more than others were under nourished. Poor economic status is a risk factor for under nutrition in this area.

Keywords: Children, Iran, nutrition, sociodemographic

INTRODUCTION

In spite of increasing obesity in the last decade, under nutrition in children is the largest contributor to global burden of disease and causing heavy health expenditures in developing countries especially in Asia[1] and is related to about half of all child deaths in world.[2] Malnutrition has been decreased[3] in Asia, but it was remained in preschool children from 16.0% in China to 64.0% in Bangladesh.[4] Under nutrition as a health problem among under 2 years children was seen in Birjand-Iran[5] and nutritional disorders among Iranian children especially in rural area has been reported in CASPIAN-III study.[6] Stunting, underweight, and wasting were common in 9.23%, 9.66% and 8.19% of under-six children in Fars province (South of Iran).[7]

Secular growth differences among ethnic groups have been seen in USA.[8] The role of genetic factors on the secular growth was shown in Sri Lanka Australian children.[9] Using free fat mass (FFM) instead of body mass index (BMI) in filed studies[10] and design a regional growth chart has been recommended by researchers.[11] The influence of perinatal factors on further growth for prevention of growth disorders has been approved in a longitudinal study in Iran.[12]

Anthropometry is an easy tool for assessing nutritional status in individuals and communities and offers the advantages of objective evidence with relatively low technology. The childhood malnutrition is complex and these etiology involved biological, cultural and socioeconomic influences.[13]

Of 1.7 million populations in the Golestan province (North of Iran), 43.9% and 56.1% are living in urban and rural area, respectively. The main job of rural population is agriculture and different ethnic groups such as Fars-native, Turkman and Sistani are living in this region.[14]

Besides obesity,[15,16] under nutrition and growth failure are the health problems in Iranian children.[17,18,19] This study was conducted to compare the nutritional status of under five children among three ethnic groups (Fars-native, Turkman and Sistanish) and attempted to analyze sociodemographic related factors same as economic status, location area, parent's educational level and gender influence on nutrition status in those children. Data on children with under nutrition and the possible role of social inequity help to establish a proper preventive program.

METHODS

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study, which carried out on 2530 (637 = Fars-native, 1002 = Turkman and 891 = Sistani) from 21 villages in the North of Iran in 2013. Villages were chosen by random sampling among 118, and all of under-five children were chosen by simple sampling. To avoid the data collection errors, a 21-health staff team has been learned before starting the study. The calculated sample sizes of 2401 respondents at least were needed for a 95% confidence and a maximum marginal error 0.02. For all of cases, a questionnaire with contain questions on the socialdemographic condition of families of children same as location area, ethnicity, family economic status, and parent's educational level was completed by interview. The validity of questionnaire has been obtained from scientific sources and reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient and found to be 0.83.

Anthropometric measurements of the children were performed in light dress and without shoes in the morning. Body-weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a balanced-beam scale, and height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm with standing up and head, back, and buttock on the vertical land of the height-gauge. The height of children, who are not able to stand, were measured in a lying posture.

In this study, children's anthropometric data were compared with those in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference population, which has been approved by WHO.[20] The parameters used for body index were the following: Weight/age (WAZ) as the present nutrition indicator or underweight, height/age (HAZ) as the past nutrition indicator or stunting, weight/height (WHZ) as the present and past nutrition indicator or wasting.[21]

Z-score was used for nutritional classification with following category: Normal: ≤ −1 Z-score, slight malnutrition = between − 1 Z-score and − 2 Z-score, moderate malnutrition = between − 2 Z-score and − 3 Z-score and severe malnutrition = <−3 Z-score. Under nutrition was defined as a underweight, stunting and wasting <−2 Z-score.[20,22]

The ethnic groups were divided into three groups: (1) Fars-native: The natural inhabitant of this province, which they are recognized with same name in the society. (2) Turkman: The inter marriage of this ethnic group with other ethnic groups were rare therefore this ethnic group can be recognized as pure race. (3) Sistani and Bluch ethnic group: This ethnic group were immigrated from Sistan and Bluchestan province from the east of Iran far earlier.

Economic status was categorized based on possession of 16 consumer items considered necessary for modern-day life such as telephone, running water, gas pipeline, home ownership, color television, LED or LCD television, PC computer, modern refrigerator, private car, cooler, mobile, dishwasher, washing machine, bathroom, DVD player and microwave oven or toaster oven. According to this list, the economic status of sample population study as followed: Poor ≥ 6, moderate = 7–10 and high-income = 11–16.

According to regular education in Iran, educational level categorized in three groups: (1) Uneducated, (2) 1–12 years schooling and (3) college.

SPSS 18.0 (Chicago II, USA) software was used for statistical data analysis. Chi-square test was used for qualities groups and P value under 0.05 included significations. The mothers who did not like to participate in our study has been excluded.

This study approved by Ethical Research Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (G-P-35-1112). Verbal informed consent was received from all cases.

RESULTS

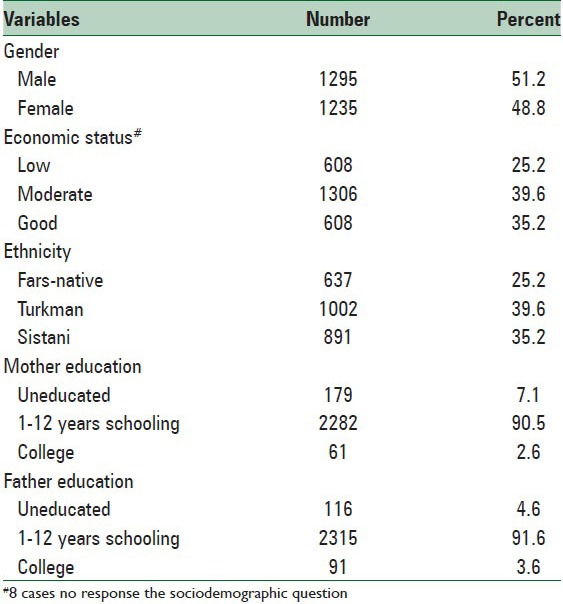

Distribution of the baseline characteristics of the study population presented in Table 1. Generally, 51.2% are boys and the proportion of ethnicity was 25.2%, 39.6% and 35.2% in Fars-native, Turkman and Sistani, respectively. Distribution of subjects in three economic levels was 24.1% in low, 51.8% in moderate and 24.1% in good level. Illiteracy was seen 7.1% and 4.6% in mother and father, respectively. Eight individuals did not respond to socioeconomic questions.

Table 1.

Distribution of the baseline characteristics of the study population (n=2530)

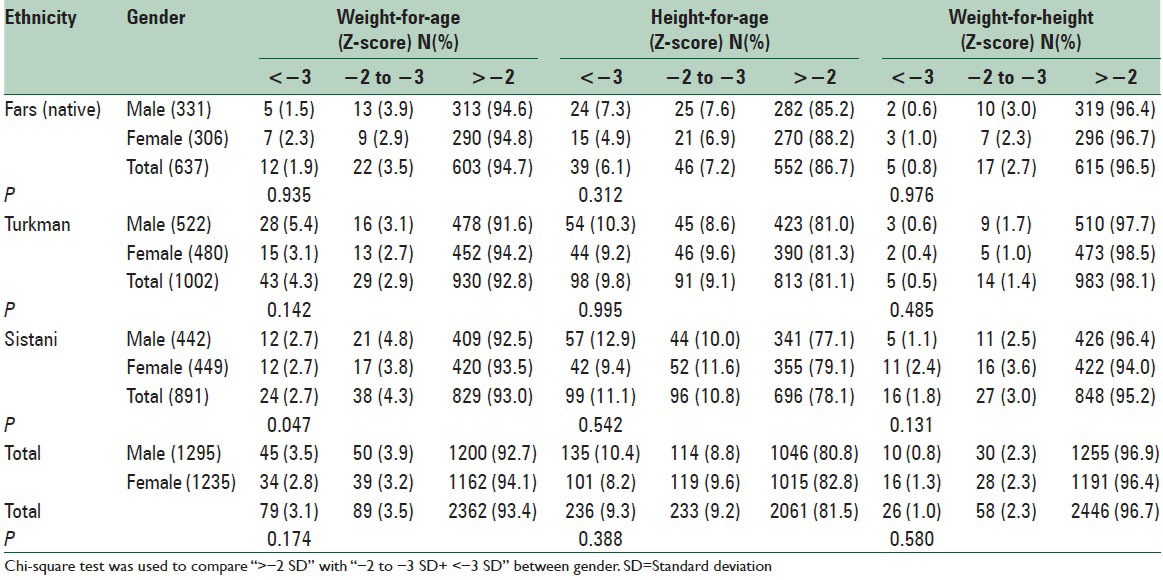

The comparison of under nutrition among under-5-year children in three ethnic groups is presented in Table 2. As a whole, under nutrition (<−2 Z-score) was observed in 6.6%, 18.5% and 3.3% based on underweight, stunting and wasting, respectively. The prevalence of under nutrition was more common in boys than in girls. Based on underweight and stunting, under nutrition was seen in Sistani more than other ethnic groups. In ethnic groups; the malnutrition was not significant in genders. Among three ethnic groups, stunting was significant in boys (P = 0.013) and in girls (P = 0.004), but wasting was significant only in girls (P = 0.001). Statistical significant differences was seen based on stunting in boys between Fars-native and Sistani (P = 0.005) and in girls between Fars-native and Turkman (P = 0.009) and in Fars-native and Sistani (P = 0.001). Statistical differences were not significant between other comparing groups.

Table 2.

The comparison of under nutrition among under-5-year children in three ethnic groups in the North of Iran

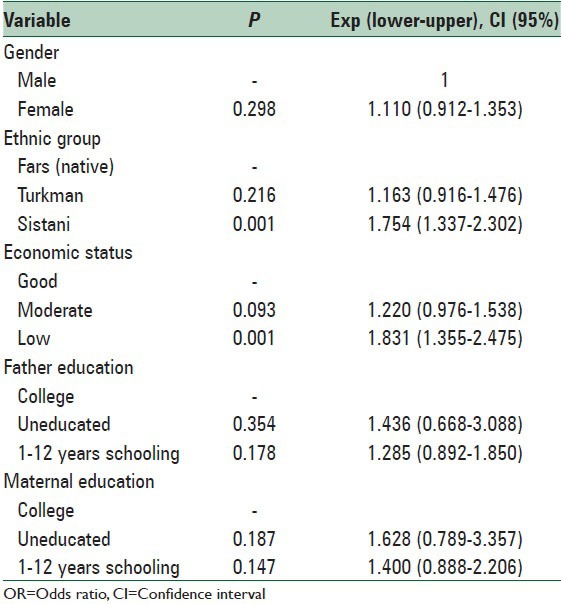

The estimated odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval of malnutrition was obtained from logistic regression as shown in Table 3. Compared with good economic group, the OR was 1.831 in poor economic groups (P = 0.001). The risk of malnutrition in Sistanish ethnic group was 1.754 times more than Fars-native group (P = 0.001). The OR was not significant in Turkaman group compared with Fars-native group, in gender and in educational levels.

Table 3.

OR for under nutrition among under-5-year children in the North of Iran

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of malnutrition based on underweight, stunting and wasting was estimated 6.6%, 18.5% and 3.3% among children, respectively, in rural area in the North of Iran. The prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting was estimated 4.3%, 8.7% and 7.5% in West Azerbaijan province in West of Iran[23] and 7.5%, 12.5% and 4.4% in Khorasan province Northeast of Iran,[24] respectively. In a rural area in the North of Iran, under nutrition was seen in 3.20%, 4.93% and 5.13% based on underweight, stunting and wasting, respectively.[25]

According to UNICEF report, 11%, 15% and 5% of Iranian under-5-year children were in underweight, stunting and wasting, respectively.[3] In a comparison study,[26] the prevalence of under nutrition in 2–18 years old children among Chinese, Indonesian and Vietnam has been shown 0.6%, 10% and 13% in boys and 10%, 13% and 19% in girls, respectively. Compared with above studies, stunting noticeably is high in the North of Iran. Zinc deficiency is a health problem in Iran and it can be a susceptible factor for failure to thrive in the Northern children.[27,28]

We found statistically significant differences between prevalence of under nutrition among three ethnic groups living in the North of Iran with a higher rate in Sistanish ethnic group. Nutrition differences among ethnic groups were reported both in Iran[29] and in other countries.[30,31] BMI distribution was different among ethnic populations in US.[32] The association between child weight loss and parent's education, family income and other sociodemographic factors was observed in white, black, Spanish and Asian residence in USA.[33] Non-Hispanic children more than Hispanic children suffer from stunting.[34] Rush[10] recommended using FFM index instead of BMI in field studies. Fredrik et al.[11] found out that separate growth chart is necessary for Moroccan and Turkish children are living in Netherland. The higher prevalence of malnutrition in Sistani ethnic group may be related to biological, cultural and socioeconomic influences. It is necessary to assess in future studies. On the other hand, low economic status was found to be as potential risk factor for under nutrition in this study. The poor nutrition has been shown in Sistanish group compared with other ethnic groups in the North of Iran.[25,34,35]

Consistence with following studies, we have shown the poor economic status as a risk factor for malnutrition. Cultural status, income level, food behavior and less health care were known as the risk factor for malnutrition.[31] Block[36] believed that low income families are less aware of their food needing. In Iran,[37] sociodemographic factors influence on nutritional education with an improving of health criteria. Thereby, for control of malnutrition in under-5-year children, the sociodemographic related factors as an underling causes should be considered.

We did not assess the food intake, economic status based on income and sample size was not estimated by ethnic proportion. In addition, the statistical power will be increased if we used the design effect. These are limiting factors for our study.

CONCLUSIONS

Under nutrition has been reminded as a health problem among under-5-year children in rural area in the North of Iran and stunting was seen in an alarming rate among them. Under nutrition has been common in Sistanish children more than other ethnic groups’ children. Poor economic status is a risk factor for under nutrition in this area.

Public health programs that aim to reduce malnutrition should primary focus on the low economic especially in Sistani ethnic group. To establish a comprehensive study for determining the substantial malnutrition factors based on ethnic characteristics is necessary in future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jafar TH, Qadri Z, Islam M, Hatcher J, Bhutta ZA, Chaturvedi N. Rise in childhood obesity with persistently high rates of undernutrition among urban school-aged Indo-Asian children. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:373–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.125641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361:2226–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Child Malnutrition. UNICEF. [Last cited on 2011 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/specialsession/about/sgreport-pdf/02_ChildMalnutrition_D7341Insert_English.pdf .

- 4.Khor GL. Update on the prevalence of malnutrition among children in Asia. Nepal Med Coll J. 2003;5:113–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namakin K, Sharifzadeh GR, Zardast M, Khoshmohabbat Z, Saboori M. Comparison of the WHO Child Growth Standards with the NCHS for Estimation of Malnutrition in Birjand-Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:653–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahmanian M, Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Shafiee G, Aminaee T, et al. Dual burden of body weight among Iranian children and adolescents in 2003 and 2010: The CASPIAN-III study. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:96–103. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.40735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavosi E, Hassanzadeh Rostami Z, Kavosi Z, Nasihatkon A, Moghadami M, Heidari M. Prevalence and determinants of under-nutrition among children under six: A cross-sectional survey in Fars province, Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:71–6. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Ogden CL, Dietz WH. Racial and ethnic differences in secular trends for childhood BMI, weight, and height. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:301–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wickramasinghe VP, Cleghorn GJ, Edmiston KA, Davies PS. Impact of ethnicity upon body composition assessment in Sri Lankan Australian children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:101–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rush EC, Puniani K, Valencia ME, Davies PS, Plank LD. Estimation of body fatness from body mass index and bioelectrical impedance: Comparison of New Zealand European, Maori and Pacific Island children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1394–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredriks AM, van Buuren S, Jeurissen SE, Dekker FW, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Wit JM. Height, weight, body mass index and pubertal development references for children of Moroccan origin in The Netherlands. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:817–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseini SM, Maracy MR, Sarrafzade S, Kelishadi R. Child Weight Growth Trajectory and its Determinants in a Sample of Iranian Children from Birth until 2 Years of Age. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:348–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz ML. Family health effects: Complements or substitutes. Health Econ. 2001;10:699–714. doi: 10.1002/hec.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistical Center of Iran. Population and Housing Census. [Last cited on 2011 May 23]. Available from: http://www.sci.org.ir .

- 15.Mirmohammadi SJ, Hafezi R, Mehrparvar AH, Rezaeian B, Akbari H. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Iranian school children in different ethnicities. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21:514–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelishadi R, Haghdoost AA, Sadeghirad B, Khajehkazemi R. Trend in the prevalence of obesity and overweight among Iranian children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2014;30:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delvarianzadeh M, Sadeghian F. Malnutrition prevalence among rural school students, Payesh. J Iran Inst Health Sci Res. 2006;5:263–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basiri Moghadam M, Ghahramany M, Chamanzary H, Badiee L. Survey of prevalence of malnutrition in children who studies at grade one in Gonabad primary school in 2005-2006. Ofogh E Danesh. 2007;13:40–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darvishi S, Saleh Hazhir M, Reshadmanesh N, Shahsavari S. Evaluation of malnutrition prevalence and its related factors in primary school students in Kurdistan Province. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2009;14:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharifzadeh G, Mehrjoofard H, Raghebi S. Prevalence of Malnutrition in under 6-year Olds in South Khorasan, Iran. Iran J Pediatr. 2010;20:435–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidibé T, Sangho H, Traoré MS, Konaté FI, Keita HD, Diakité B, et al. Management of malnutrition in rural Mali. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:142–3. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fml061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrokh-Eslamlou HR. Geographical distribution of nutrition deficiency among children under five years old in the west Azerbaijan province, Iran. Urmia Med J. 2013;24:201–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payandeh A, Saki A, Safarian M, Tabesh H, Siadat Z. Prevalence of malnutrition among preschool children in northeast of Iran, a result of a population based study. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:208–12. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veghari G. The Relationship of ethnicity, socio-economic factors and malnutrition in Primary School Children in North of Iran: A cross-sectional study. J Res Health Sci. 2012;13:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuan NT, Nicklas TA. Age, sex and ethnic differences in the prevalence of underweight and overweight, defined by using the CDC and IOTF cut points in Asian children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1305–12. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehghani SM, Katibeh P, Haghighat M, Moravej H, Asadi S. Prevalence of zinc deficiency in 3-18 years old children in Shiraz-Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13:4–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandstead HH. Zinc deficiency. A public health problem? Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:853–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160080029016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veghari G, Golalipour MJ. The Comparison of nutritional status between Turkman and non-Tutkman ethnic groups in North of Iran. J Appl Sci. 2007;7:2635–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larrea C, Kawachi I. Does economic inequality affect child malnutrition? The case of Ecuador. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:165–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renzaho AM, Gibbons C, Swinburn B, Jolley D, Burns C. Obesity and undernutrition in sub-Saharan African immigrant and refugee children in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15:482–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Moreno LA, Caballero B, Cole TJ. Limitations of the current world health organization growth references for children and adolescents. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:S175–88. doi: 10.1177/15648265060274S502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM. The relationship of ethnicity, socioeconomic factors, and overweight in US adolescents. Obes Res. 2003;11:121–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veghari G, Mansourian AR, Marjani A. The comparison study of the anemia among three different races of women of Fars (native), Torkman and sistanee in the villages around Gorgan Iran (South–east of Caspian Sea) J Med Sci. 2007;7:315–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veghari G, Asadi J. Impact of ethnicity upon body composition assessment in Iranian Northern Children. J Clin Diagn Res. 2009;3:1779–83. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Block JP, Scribner RA, DeSalvo KB. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income: A geographic analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salehi M, Kimiagar SM, Shahbazi M, Mehrabi Y, Kolahi AA. Assessing the impact of nutrition education on growth indices of Iranian nomadic children: An application of a modified beliefs, attitudes, subjective-norms and enabling-factors model. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:779–87. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]