Abstract

Effectiveness of school-based interventions to prevent or control overweight and obesity among school children was reviewed for a 11-year period (January 2001 to December 2011). All English systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reviews of reviews, policy briefs and reports targeting children and adolescents which included interventional studies with a control group and aimed to prevent or control overweight and/or obesity in a school setting were searched. Four systematic reviews and four meta-analyses met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Results of the review indicated that implementation of multi-component interventions did not necessarily improve the anthropometric outcomes. Although intervention duration is a crucial determinant of effectiveness, studies to assess the length of time required are lacking. Due to existing differences between girls and boys in responding to the elements of the programs in tailoring of school-based interventions, the differences should be taken into consideration. While nontargeted interventions may have an impact on a large population, intervention specifically aiming at children will be more effective for at-risk ones. Intervention programs for children were required to report any unwanted psychological or physical adverse effects originating from the intervention. Body mass index was the most popular indicator used for evaluating the childhood obesity prevention or treatment trials; nonetheless, relying on it as the only indicator for adiposity outcomes could be misleading. Few studies mentioned the psychological theories of behavior change they applied. Recommendations for further studies on school-based interventions to prevent or control overweight/obesity are made at the end of this review.

Keywords: Child, intervention studies, obesity, review, school

INTRODUCTION

Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents have become increasing health problems worldwide.[1,2,3,4] Obesity in childhood is an independent risk factor for adult obesity and has been linked to physical, social and psychological consequences including increased risk for noncommunicable disease, social stigmatization resulting in sadness and loneliness, engagement in high-risk behaviors and undesirable stereotyping.[5,6,7]

While action to combat obesity is urgently required, such action must be based on the best available evidence to guarantee optimal outcomes.[8] The existing body of evidence includes studies which have targeted their interventions in various settings such as clinic, home, community centers and schools. Schools have been among the most suitable venues of interventions[9] because they are unique in some aspects. They create a crucial social environment for children:

Intrinsically expose them to dietary and physical activity (PA) factors

Students spend a significant part of their lives in schools

School-based interventions have the possibility to reach almost all the children in a short time; and

Affect socio-cultural, and policy characteristics of the surrounding environment to promote nutritional and PA states[1,2,10]

This article is a systematic review of reviews. This study provides an overview of interventions aimed at treating or preventing overweight and/or obesity during childhood and adolescence. We sought to define what interventions are effective, who may benefit more, and in which circumstances.

METHODS

Literature search

The relevant studies published between January 2001 and December 2011 were searched. We used the following databases to find any systematic review, meta-analysis, policy brief or report regarding the objective of our review:

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

PubMed, Cochrane library, Web of knowledge/All databases, ProQuest, Embase, Health Systems Evidence (McMaster University) - health-evidence.ca - Health Information Research Unit, HIRU - Hedges, REA Methods (Rapid Evidence Assessment).

Policy briefs and reports

Capacity Workforce, COHRED, EVIPNet Africa, Global and Social Policy Program, Global Health Council, Health Action International, Health Systems Evidence, McMaster University, Management Sciences for Health, Supporting Policy relevant Reviews and Trials Summaries, World Bank: Health Results Innovation Trust Fund, World Health Organization: Department of Health Systems Financing, World Health Organization: The World Health Report 2006 - “Working together for Health.”

The strategy of search for PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Knowledge, ProQuest and Embase is available in [Appendixes 1 and 2]. For other databases, we used MeSH term “obesity” or “overweight,” “child” and “prevention” singly and/or in combination.

Eligibility criteria

Phase 1

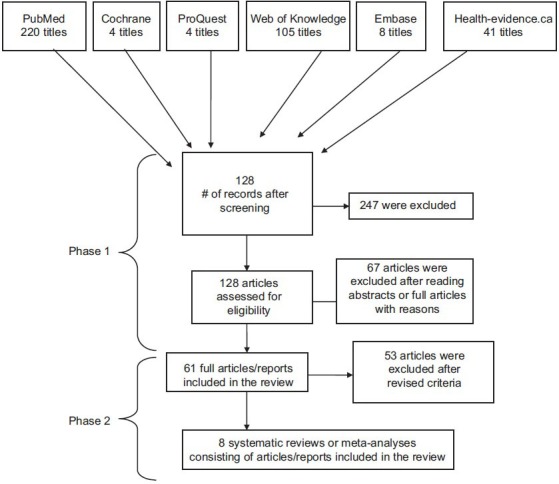

All English, full articles on systematic reviews, meta-analyses, review of reviews, policy briefs and reports targeting children and adolescents, published between 2001 and 2011, with interventional studies for preventing or treatment of overweight or obesity were included in the study. For most reviews separation of combined results based on age was impossible, so that all of the childhood age groups were reviewed. Correlation and observational studies (if not combined with intervention studies), studies whose primary aim was not to intervene on overweight or obesity (i.e., interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular disease, Type II diabetes, etc.) were excluded. In this phase, 61 reviews including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reports and review of reviews were selected, extracted and appraised [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Diagram of study selection

Phase 2

To make the results more precise, comparable and applicable, we added the following exclusion criteria: all reviews of reviews, review articles which their main objective was evaluation of interventions in settings other than schools (e.g., clinic, family, community, etc.) and those which included interventional studies without a control group (e.g. pre- and post-design) were excluded [Figure 1].

Selection process

To identify the relevant studies, all titles and abstracts generated from the searches were reviewed by a reviewer (Phase 1). To determine if they met eligibility criteria, an evaluation of the full texts was then conducted by two reviewers separately. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. For the second phase, two reviewers re-evaluated 61 full articles against new selection criteria (mentioned in eligibility criteria, Phase 2) separately. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. Finally four systematic reviews and four meta-analyses were included in the study [Figure 1].

Critical appraisal and data extraction

Two of the reviewers, independently, evaluated validity of all the 61 references by Critical Appraisal Skills Programs[11] focusing on methodology. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until reaching consensus. The results were derived based on the frequency of original findings [Figure 1].

RESULTS

Eight reviews (four systematic reviews and four meta-analyses) examined a total of 106 papers [Appendix 3]. In the first phase of papers selection, three reports defined as “report,” were screened, which were filtered in the second phase of selection. No policy brief was found.

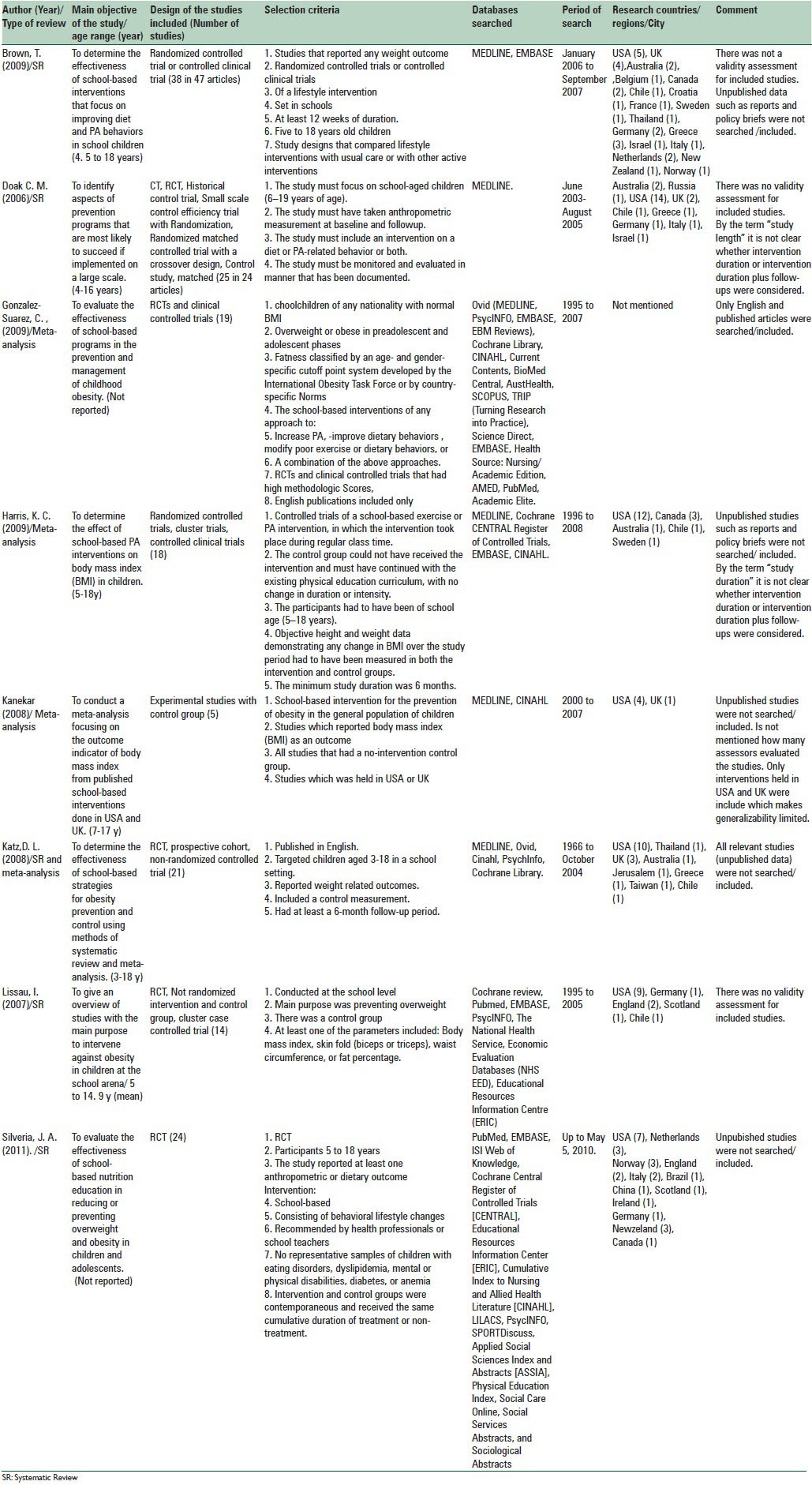

Details of the studies included in the review are displayed in Table 1. One meta-analysis did not report the age range of its included studies.[3,5] Some only considered a single strategy[5,12] such as PA or nutrition education for evaluation of the studies while others considered combined strategies.[3,13,14,15,16,17] Most of the reviews (62.5%) had quality assessment or a scoring system. The search span for included reviews and meta-analyses ranged from 1966 to 2010, which indicates we examined a period of 44 years, whereas a systematic review defined no limitation for date of beginning of the search.[5] Most primary studies were performed in the USA then in European countries.

Table 1.

Details of the studies included in the review

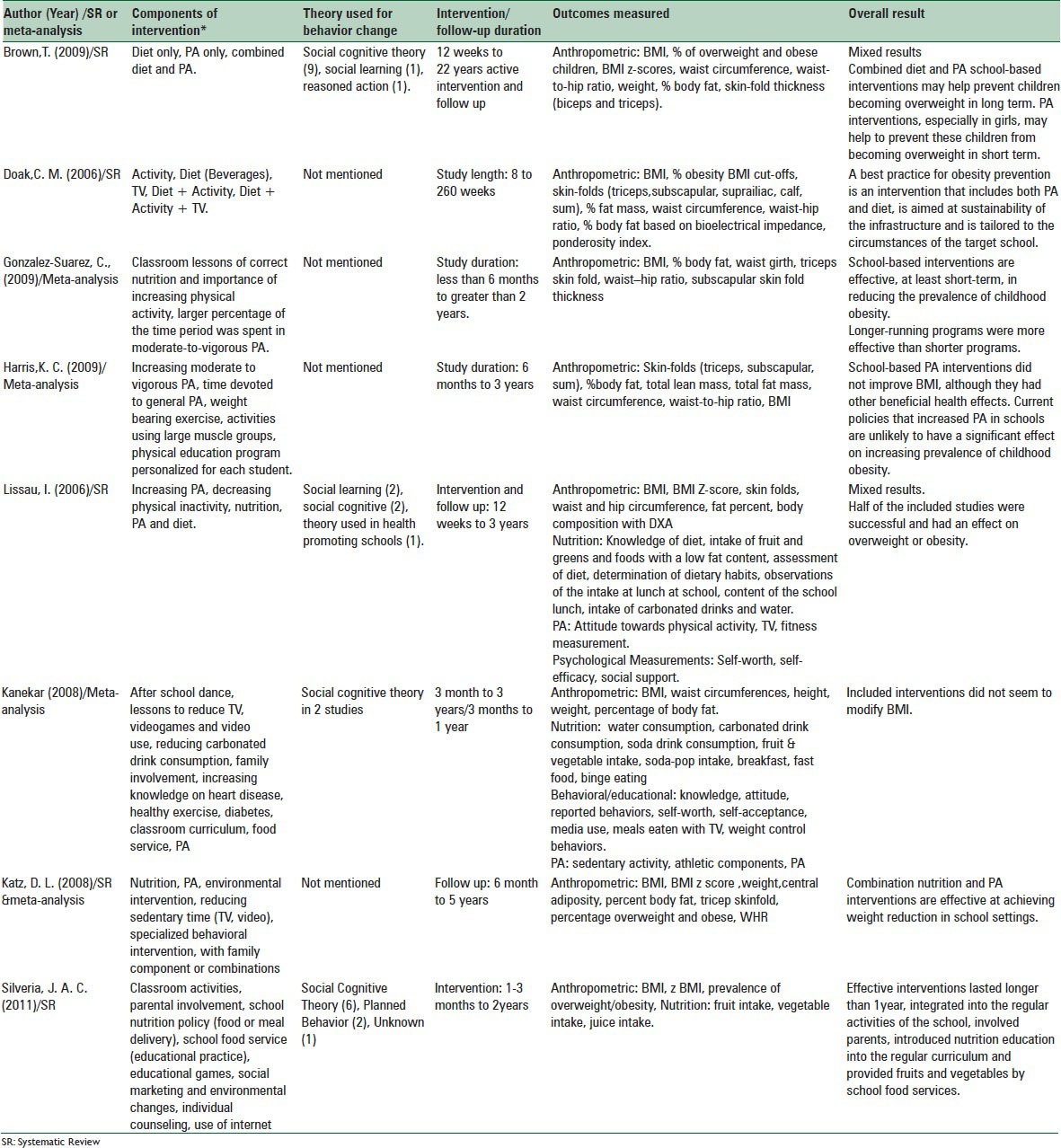

Components of the included interventions, theory used for behavior change, duration of intervention/follow-up, outcomes measured and overall results are displayed in Table 2. Half of the reviews mentioned the theory of behavior change applied in the studies, among them Social Cognitive Theory was used most (68%). Most of the reviews and meta-analyses judged the effectiveness of studies based on anthropometric outcomes[3,12,13,14,15,16,17] while one review considered anthropometric, as well as food consumption outcomes.[5]

Table 2.

Details of the interventions included in the reviewed articles

Determinants of the effectiveness in the reviewed interventions

Components of the studies

According to Table 2, one meta-analysis[16] did not test the impact of interventions’ components; however, most studies that were entered in it were multi-component and the overall result of the analysis in modification of body mass index (BMI) was not promising. Another meta-analysis[12] had analyzed only PA interventions in which no change in the body composition measures was seen. In a review which had categorized the studies based on effectiveness,[15] 17 out of 25 studies were effective, 10 of them were multicomponent, comprising diet and PA improvement, two focused on diet, two focused on PA, two focused on diet, PA and TV viewing and one only focused on TV viewing. Another review[14] reported that nine out of 20 combined interventions, one out of three dietary interventions and 10 out of 15 PA interventions were effective. In a meta-analysis,[17] combination of interventions caused a significant reduction in body weight; however, the single nutrition intervention and TV viewing reduction were equally effective, and PA intervention did not cause body weight reduction. In a meta-analysis[3] it was demonstrated that interventions which applied increased PA and classroom curriculum activities had a significant OR of reducing the prevalence of overweight and obesity. A review[13] explored that two out of four PA-focused and two out of six studies which focused on PA and diet had a significant effect on overweight. Also, two studies which focused on physical inactivity were effective, and the only study that focused on nutrition was not effective. In another review,[5] the author concluded that 10 out of 12 studies which adopted at least two among the three most common components (classroom activities, parental involvement, and school nutrition policy) were effective for overweight and obesity reduction.

Duration of the studies

Two meta-analyses[16,17] and a review[13] did not test the impact of study/intervention duration. In a meta-analysis,[12] it was not mentioned that either the impact of the intervention duration or the study duration had been analyzed. However, duration of studies did not result in BMI change, and there was no statistically significant difference between studies lasting up to 1-year and those lasting longer. A meta-analysis[3] reported that interventions which lasting more than 1-year had a higher OR of reducing the prevalence of obesity. A review[5] pointed out interventions with a duration of more than 1-year demonstrated effectiveness. In another review,[15] the mean numbers of weeks in the effective interventions were less than noneffective interventions (61 vs. 133 weeks), whereas a review[14] implied that the length of interventions was not an important variable determining effectiveness.

Participants’ characteristics

Gender

A review[14] found inconsistent effects for girls and boys. In four studies of children aged 10–14 years which applied combined diet and nutrition interventions, two interventions improved BMI significantly in boys but not girls and two other combined interventions was effective for girls, not boys. In another review,[15] among a total of 17 effective interventions, three were exclusively effective for girls, and two were effective only for boys. In a meta-analysis[17] in subgroup analysis by gender, the PA showed better statistically significant weight reduction in girls. A meta-analysis[12] assessed different response to PA intervention for boys and girls. It was demonstrated that the primary studies involving only boys or only girls did not reduce BMI significantly, and it was concluded that sex had not influenced the results of the meta-analysis. Other meta-analyses or reviews did not test the effect of gender on impacts of interventions.

Risk of disease

Two reviews reported results of projects focusing on “high-risk” children. In one review,[13] two included studies targeted high-risk children. Only one of the studies defined inactive girls with a BMI above the 75th percentile as “high-risk,” while another study mentioned no definition for “high-risk.” Results of intervention on inactive girls were not promising; however, another study caused a reduction in prevalence of overweight in the intervention group. In another review,[15] both programs targeted “high-risk” children were effective.

Ethnicity

Only one review[15] reported a study based on ethnicity. The study was not effective in any ethnic group. However, a statistically significant increase was seen in BMI and skin-fold measures in African American children compared with controls. This result was not observed in the white or hispanic children.

Age range

In one review, it was shown that 65% of noneffective interventions included children 8–10 years old.[15]

Other aspects of the reviewed interventions

Primary outcomes in the interventions

In two meta-analyses[12,16] and two reviews,[5,14] BMI was reported as the only indicator of the effectiveness for the interventions. Three meta-analyses and reviews considered BMI in addition to other indicators of adiposity including prevalence of overweight and/or obesity, waist circumference, body weight, skin-fold, and body fat. In one meta-analysis, body weight was reported as the only primary outcome.[17] In three meta-analyses,[3,12,16] the interventions did not decrease BMI compared with control groups, significantly; however, in one of the[3] intervention programs had reduced significantly overweight and obesity prevalence. In a review,[5] despite overall positive effects of included studies on anthropometry and food intake, eight of nine interventions which assessed BMI were not successful to reduce it. In one review,[14] which had mixed results for effectiveness, 14 out of 38 studies demonstrated significant positive effect for BMI: In 4 studies BMI increased in the control group while it did not change in the intervention group; in another 4 studies BMI decreased significantly as compared to the control value; finally, in 6 studies BMI increased, although the increase was lower than the control group. In another review,[15] 17 out of 25 of interventions were effective based on the reduction of either BMI or skin folds and only four were effective by both variables. In a review, half (seven) of the studies had a significant effect on anthropometric measures, among them three had a significant effect on BMI. In one study lower BMI was seen in the intervention group, in one study higher PA was correlated with lower BMI and in another study lower increase of BMI was seen in the intervention group as compared with the control group.[13]

Application of theoretical frameworks in the interventions

Four reviews and meta-analyses did not mention and test the theory of behavior change used in the single studies.[3,12,15,17] One meta-analysis[16] and two reviews[5,14] mentioned names of theories used in primary studies but did not assess their effectiveness. In one review,[13] five studies had applied psychological theories in which two studies applying social cognitive theory had a significant effect on overweight.

Adverse effects of interventions

Only one review[15] reported unhealthy outcomes of included interventions. In the review, 3 primary studies commented on the intervention effect on underweight in the studied group. One study did not show change in underweight and no reduction in overweight or obesity. Another study showed a significant increase in underweight prevalence together with a significant reduction in overweight and obesity prevalence, and the other reported the impact of the intervention on underweight, normal weight and overweight separately. In the review, three interventions caused no weight reduction but showed a statistically significant increase in weight for height. In the review, stigmatization as a result of a study was reported among obese children and also obese teachers, as deliverers of interventions.

Sustainability of studies

Two reviews evaluated probable barriers for sustainability of school-based interventions.[14,15] In one of reviews,[15] the authors expressed some studies that had discussed sustainability in different aspects. In an intervention designed to maximize the effect without adding resources or staff, although the intervention was not successful by anthropometric measures, diet of children was improved significantly. In another intervention, the author referred to cost as a barrier for change in school food service. A 12-week intervention was effective in girls had given an accounting of the cost which implied a low-cost approach. However, another lower cost intervention which prepared well-designed printed materials was not effective compared to a similar intervention which applied audiovisuals and meetings with parents and teachers and was effective. Another important point which is reflected in a study of this review, which in turn may make difficulties for participation and consequently sustainability of obesity interventions, is stigmatization of obese children. In a study, it was mentioned that programs beside obese children may stigmatize obese teachers as role model and deliverers of the education-based interventions. Another obstacle for sustainability, which was addressed in two studies, was limitation of time in school curriculum and concerns of parents and staff about children's class performance. In Brown and Summerbell review,[14] it was discussed that in most of studies deliverers of interventions were existing staff trained by researchers and multipronged interventions had a tendency to engage more school personnel and to be added to the curriculum. However, despite being more likely to be sustainable such interventions were not necessarily successful.

Taken together, although parents responded to changes in diet and PA positively, these changes did not lead to behavior change or BMI change. In a study provision of free breakfasts in schools, made the children satisfied during the intervention, but it was not continued when the breakfast was stopped. In a PA, intervention girls expressed that because of the noise and the low importance of being physically active as compared with doing homework or chores their parents discouraged PA at home. One feasibility study concluded that it would be too expensive and unsustainable to deliver the intervention by nonschool personnel.

DISCUSSION

Although it is suggested that multipronged interventions may be more promising in childhood obesity prevention or treatment,[5,14,18,19] some single-component studies which are concentrated on strategies involving dietary or PA component or reducing sedentary behaviors, have been also shown to have a positive impact on adiposity outcomes.[20,21,22,23] Some authors discussed that PA interventions may be more successful for girls and younger children.[14] Nonetheless, the overall results are mixed and by the existing data we cannot elucidate a consistent pattern in favor or against any intervention components. Interventions which target both nutrition and PA will bring health benefits even though currently there is no evidence of their superiority, at least in adiposity modification, over other kinds of intervention.

As regards “study duration,” overall results indicate that the duration of the intervention is an important determinant of effectiveness. Nonetheless, it is not clear how long it takes to have a successful program. The length of periods reported for an effective intervention ranged between 3 and 24[2] and 6 months.[18] More studies are required in this area.

Results regarding gender and effectiveness of programs are mixed and do not lead us toward a practical solution. A systematic review indicated that interventions on a social learning basis may be more suitable for girls while environmental programs which provide the possibility of PA may be more appropriate for boys.[24] Nonetheless, other systematic reviews concluded programs targeting females appear to be more effective irrespective of their components.[25,26] It is not clear which elements in various interventions may cause participants to respond differently. To understand the underlying mechanisms generating the difference we need to look at the issue from different points of view. It is documented that boys and girls are different in development of motor skills, body composition, and feeling free to participate in activities outside the home; while girls’ role models are less physically active, there are more barriers and less perceived advantages of PA for girls, and on the subject of diet interventions, girls are more concerned about their body weight and image compared to boys.[14,26] In tailoring future interventions, the points should be considered properly.

In some trials, high-risk children were targeted. Although the nontargeted or primary prevention studies are more effective and have an impact on a large number of participants,[2,27] this type of interventions may not be effective enough among those who are most in need.[27] In a systematic review, it is documented that when participants are at a higher risk of overweight or obesity the interventions are more successful.[28] Another systematic review[29] which sought to find effectiveness of prevention or early treatment of overweight and obese children urged for future theory-based reproducible interventions with at-risk young children.

Age- and sex-specific BMI is the most frequently used and reported outcome for childhood overweight and obesity. It is the most popular outcome because of its feasibility and validity[1,16] and is widely used in different studies.[14] Nonetheless, it is worth noting that relying on BMI as the only outcome of adiposity may be insufficient and inappropriate and consequently, misleading.[13,15] It is relatively an insensitive variable to change[30] and cannot fully reflect changes in body composition.[31] Especially in interventions in which PA is included using of BMI as an indicator of obesity, may be misleading because of an increase in lean body mass. It is argued that body composition is more informative and better than its proxies, such as BMI or weight.[22,31] So, to evaluate the effectiveness of different interventions we recommend applying other proxy measures of body composition, such as skin folds, %body fat and waist girth.

Despite the fact that the majority of the reviews included in this review either did not test or even mention the psychological theory used, application of them may be very useful. The psychological theories for understanding the underlying mechanisms which change behavior are needed, and they can help us to explain the reasons why some school-based interventions work.[2]

There are few studies assessing the probable adverse effect of childhood prevention or treatment interventions. Beside physical adverse effects, such as underweight or overweight, psychological effects need to be evaluated. It is noted that the interventions mentioned must first, “do no harm.”[32]

Long-term follow-up is necessary to evaluate the sustainability. In this review, some barriers to sustainability are explained. They include high costs, stigmatization of both obese children and teachers as deliverers of interventions, limitation of time and concerns of parents and school staff about class performance, and provision of free meals as potential barriers of durability.

CONCLUSIONS

It can be concluded that multi-component interventions seem to have superiority over single component interventions in adiposity reduction. Though adding components to an intervention may not have an immediate effect on adiposity outcomes, it yields many health benefits other than adiposity reduction. Whereas duration of interventions is a determinant of effectiveness, for a definitive judgment more studies are needed. There are differences between girls and boys in terms of physiological, psychological and cultural dimensions. Before tailoring the interventions, the differences should be taken into consideration. Even though, primary prevention is more effective for a large population, this type of interventions may not reach appropriately those who are most in need.

Body mass index is a feasible indicator of obesity and currently is widely used in different studies worldwide; however, it should not be applied as the only criterion for reduction of adiposity. Other measures like skin fold thickness and body composition are reliable outcomes which can be used to define adiposity status among children.

Despite the worth of psychological theories for understanding the underlying mechanisms of behavior change the majority of the studies here, either did not test or mention the psychological theory they used. Evaluation of unwanted effects of an intervention such as underweight, eating disorders, stigmatization and low self-esteem is essential. Sustainability is a key element for evaluation of study effectiveness. Before beginning of an intervention, it is vital to assess and overcome probable barriers.

Recommendations for further school-based studies

-

1

It is recommended to implement multi-component interventions to prevent or treat childhood obesity

-

2

The gender differences should be taken into consideration before tailoring the interventions

-

3

Application of psychological theories which help us to understand mechanisms of behavior change and the reasons for achievement of some interventions is suggested

-

4

Body mass index should not be applied as the sole criterion for adiposity reduction studies/program

-

5

It is crucial to evaluate not only wanted but also unwanted effects of an intervention

-

6

Before initiation of a program, assessment and overcoming potential barriers to implementation are essential. Obviously, support for policy makers and planners is extremely important.

APPENDIX 1

Pub med

(((meta-analysis [pt] OR meta-analysis [tw] OR metanalysis [tw]) OR ((review [pt] OR guideline [pt] OR consensus [ti] OR guideline* [ti] OR literature [ti] OR overview [ti] OR review [ti]) AND ((Cochrane [tw] OR Medline [tw] OR CINAHL [tw] OR (National [tw] AND Library [tw])) OR (handsearch* [tw] OR search* [tw] OR searching [tw]) AND (hand [tw] OR manual [tw] OR electronic [tw] OR bibliographi* [tw] OR database* OR (Cochrane [tw] OR Medline [tw] OR CINAHL [tw] OR (National [tw] AND Library [tw]))))) OR ((synthesis [ti] OR overview [ti] OR review [ti] OR survey [ti]) AND (systematic [ti] OR critical [ti] OR methodologic [ti] OR quantitative [ti] OR qualitative [ti] OR literature [ti] OR evidence [ti] OR evidence-based [ti]))) BUTNOT (case* [ti] OR report [ti] OR editorial [pt] OR comment [pt] OR letter [pt])) AND (obes* OR overweight) AND (child*) AND (prevention) 220 titles, 89 selected by title.

APPENDIX 2

Strategy of search for Cochrane library, Web of knowledge, ProQuest and Embase

Cochrane library

All of The Cochrane Library

Child* OR adolesc* in Title, Abstract or keyword

Obes* OR overweight in Title, Abstract or keyword

Prevent* in Title, Abstract or keyword

Intervent* in Title, Abstract or keyword

4 titles, 1 selected by title

Web of knowledge/All databases/2001-2011

Child* OR adolesc* in Title

Obes* OR overweight in Title

Prevent* in Title

Intervent* in Title

105 title, Refine to systematic review OR meta-analysis, 22 selected by title ProQuest

Child* OR adolesc* in Citation and Abstract Obes* OR overweight in Citation and Abstract Prevent* in Citation and Abstract Intervent* in Citation and Abstract Multiple database:1363

4 titles, Refined by date, review, full text, 2 selected by title Embase

Child* obesity in title Limited by Reviews 10 titles, 0 selecte

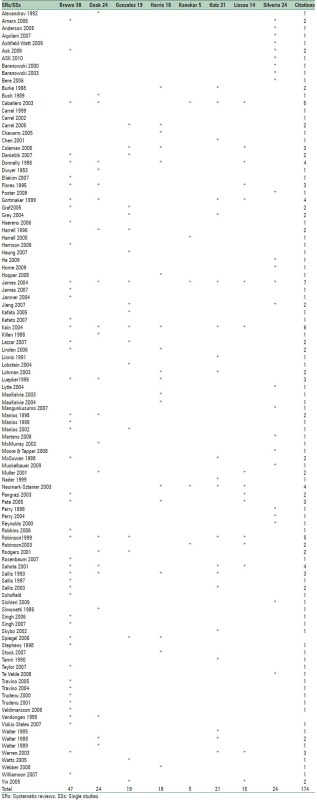

APPENDIX 3: CITATION ANALYSIS OF THE STUDIES INCLUDED

Footnotes

Source of Support: This project is funded by Knowledge Utilization Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khambalia AZ, Dickinson S, Hardy LL, Gill T, Baur LA. A synthesis of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based behavioural interventions for controlling and preventing obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13:214–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safron M, Cislak A, Gaspar T, Luszczynska A. Effects of school-based interventions targeting obesity-related behaviors and body weight change: A systematic umbrella review. Behav Med. 2011;37:15–25. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2010.543194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Suarez C, Worley A, Grimmer-Somers K, Dones V. School-based interventions on childhood obesity: A meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:418–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Cauwenberghe E, Spittaels H, Oppert JM, Rostami C, Brug J, et al. School-based interventions promoting both physical activity and healthy eating in Europe: A systematic review within the HOPE project. Obes Rev. 2011;12:205–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silveira JA, Taddei JA, Guerra PH, Nobre MR. Effectiveness of school-based nutrition education interventions to prevent and reduce excessive weight gain in children and adolescents: A systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2011;87:382–92. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters E, Armstrong R, Swinburn B, Moore L, Dobbins M, Anderson L, et al. An exploratory cluster randomised controlled trial of knowledge translation strategies to support evidence-informed decision-making in local governments (The KT4 LG study) BMC Public Health. 2011;11:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O’Malley C, Stolk RP, et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD001872. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001872.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth ML. Addressing childhood obesity: The evidence for Action. Canadian Association of Paediatric Health Centres; 2004. [Last cited on 2015 Apr 13]. Available from: Available from:http://www.healthevidence.org/view-article.aspx?a=20969 .

- 9.Thomas H. Obesity prevention programs for children and youth: Why are their results so modest? Health Educ Res. 2006;21:783–95. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Cauwenberghe E, Maes L, Spittaels H, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Oppert JM, et al. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: Systematic review of published and 'grey' literature. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:781–97. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critical Appraisal Skills Programmes (CASP) [Last cited on 2015 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_64047_en.pdf .

- 12.Harris KC, Kuramoto LK, Schulzer M, Retallack JE. Effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index in children: A meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2009;180:719–26. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lissau I. Prevention of overweight in the school arena. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2007;96:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown T, Summerbell C. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: An update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes Rev. 2009;10:110–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doak CM, Visscher TL, Renders CM, Seidell JC. The prevention of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A review of interventions and programmes. Obes Rev. 2006;7:111–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanekar A, Sharma M. Meta-analysis of school-based childhood obesity interventions in the U.K. and U.S. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2008;29:241–56. doi: 10.2190/IQ.29.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz DL, O’Connell M, Njike VY, Yeh MC, Nawaz H. Strategies for the prevention and control of obesity in the school setting: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1780–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bautista-Castaño I, Doreste J, Serra-Majem L. Effectiveness of interventions in the prevention of childhood obesity. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:617–22. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000036890.72029.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Y, Griffiths S, Chan EY. Community-based interventions to reduce overweight and obesity in China: A systematic review of the Chinese and English literature. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:436–48. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell K, Waters E, O’Meara S, Kelly S, Summerbell C. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2:CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins CE, Warren JM, Neve M, McCoy P, Stokes B. Systematic review of interventions in the management of overweight and obese children which include a dietary component. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2007;5:2–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2007.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reilly JJ, McDowell ZC. Physical activity interventions in the prevention and treatment of paediatric obesity: Systematic review and critical appraisal. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:611–9. doi: 10.1079/PNS2003265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kropski JA, Keckley PH, Jensen GL. School-based obesity prevention programs: An evidence-based review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1009–18. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: The skinny on interventions that work. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:667–91. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yildirim M, van Stralen MM, Chinapaw MJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W, Twisk JW, et al. For whom and under what circumstances do school-based energy balance behavior interventions work? Systematic review on moderators. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e46–57. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.566440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Dewar D, Collins CE, Plotnikoff RC, Okely AD, et al. The Nutrition and Enjoyable Activity for Teen Girls (NEAT girls) randomized controlled trial for adolescent girls from disadvantaged secondary schools: Rationale, study protocol, and baseline results. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Branscum P, Sharma M. A systematic analysis of childhood obesity prevention interventions targeting Hispanic children: Lessons learned from the previous decade. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e151–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Small L, Anderson D, Melnyk BM. Prevention and early treatment of overweight and obesity in young children: A critical review and appraisal of the evidence. (5-61).Pediatr Nurs. 2007;33:149–52. 27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamath CC, Vickers KS, Ehrlich A, McGovern L, Johnson J, Singhal V, et al. Clinical review: behavioral interventions to prevent childhood obesity: A systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4606–15. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luckner H, Moss JR, Gericke CA. Effectiveness of interventions to promote healthy weight in general populations of children and adults: A meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:491–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caeter FA, Bulik CM. Childhood obesity prevention programs: How do they affect eating pathology and other psychological measures? Psychosom Med. 2008;70:363–71. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318164f911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]