ABSTRACT

In Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) acts as an inhibitor of lytic replication. Here, we demonstrate that KSHV downregulated PARP-1 upon reactivation. The viral processivity factor of KSHV (PF-8) interacted with PARP-1 and was sufficient to degrade PARP-1 in a proteasome-dependent manner; this effect was conserved in murine gammaherpesvirus 68. PF-8 knockdown in KSHV-infected cells resulted in reduced lytic replication upon reactivation with increased levels of PARP-1, compared to those in control cells. PF-8 overexpression reduced the levels of the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated (PARylated) replication and transcription activator (RTA) and further enhanced RTA-mediated transactivation. These results suggest a novel viral mechanism for overcoming the inhibitory effect of a host factor, PARP-1, thereby promoting the lytic replication of gammaherpesvirus.

IMPORTANCE Gammaherpesviruses are important human pathogens, as they are associated with various kinds of tumors and establish latency mainly in host B lymphocytes. Replication and transcription activator (RTA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is a central molecular switch for lytic replication, and its expression is tightly regulated by many host and viral factors. In this study, we investigated a viral strategy to overcome the inhibitory effect of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) on RTA's activity. PARP-1, an abundant multifunctional nuclear protein, was downregulated during KSHV reactivation. The viral processivity factor of KSHV (PF-8) directly interacted with PARP-1 and was sufficient and necessary to degrade PARP-1 protein in a proteasome-dependent manner. PF-8 reduced the levels of PARylated RTA and further promoted RTA-mediated transactivation. As this was also conserved in another gammaherpesvirus, murine gammaherpesvirus 68, our results suggest a conserved viral modulation of a host inhibitory factor to facilitate its lytic replication.

INTRODUCTION

Gammaherpesviruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68), are associated with various malignancies and lymphoproliferative disorders (1, 2). Several cellular factors are known to regulate the lytic replication of gammaherpesvirus, ultimately contributing to viral pathogenesis (3, 4). Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) is an abundant nuclear protein that catalyzes the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of target proteins acting in DNA repair, cell cycle control, apoptosis, and gene expression (5–7). In KSHV and MHV-68 infections, PARP-1 interacts with the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ate replication and transcription activator (RTA), the molecular switch of lytic replication, thereby repressing lytic viral replication (8–11). PARP-1 is also known to be a component of the viral replication complex, increasing viral genome replication (9, 12). Previously, we showed that open reading frame 49 (ORF49) of MHV-68 interacts with PARP-1, disrupting interactions between RTA and PARP-1 and further promoting lytic replication by enhancing RTA-mediated transactivation (11). Here we report another viral strategy that modulates the activity of PARP-1 to facilitate the lytic replication of gammaherpesvirus. The PARP-1 protein was downregulated upon reactivation of KSHV, and a viral processivity factor (PF-8) encoded by ORF59 alone was sufficient and necessary to induce PARP-1 degradation. PF-8 interacted with PARP-1 and degraded it in an ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent way. KSHV PF-8 is known to play an essential role in virus genome replication by translocating viral DNA polymerase into the nucleus and assisting it with its DNA processivity activity (13–15). Meanwhile, PF-8 requires RTA for its expression and binding to oriLyt to form the replication complex (16–18). Our finding that PARP-1 degradation by PF-8 further enhanced RTA-mediated transactivation suggests an intricate feed-forward loop of the lytic replication of the virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

BC-3 and BCBL-1 cells (KSHV-positive cells) as well as S11 cells (MHV-68-positive cells) were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlas Biologicals, Fort Collins, CO, USA) supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), while HEK293T and BHK-21 cells were grown in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS (HyClone) at 37°C and 5% CO2. To induce the lytic replication of KSHV, BC-3 or BCBL-1 cells were treated with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) (20 ng/ml) for the times indicated in the figures. MHV-68 virus was originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (VR1465). The viruses were grown in BHK-21 cells and titrated by plaque assays, using Vero cells overlaid with 1% methylcellulose (Sigma) in growth medium. Five days postinfection (dpi), the cells were fixed and stained with 0.2% crystal violet in 20% ethanol. Plaques were counted to determine the titers.

Plasmids.

The PF-8 construct was prepared from BC-3 genomic DNA. The PF-8 construct was cloned into a pENTR vector of the Gateway system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by using the following primers: PF-8-F (forward, 5′-CCGGAATTCATGCCTGTGGATTTTCACTATGGGG-3′) and PF-8-R (reverse, 5′-GGGGCGGCCGCTCAAATCAGGGGGTTAAATG-3′. The entry clones were further transferred to a FLAG-tagged (pTAG-attRC1) or 6×MYC-tagged (pCS3-MT-6-MYC) destination vector containing additional sequences to generate FLAG-tagged or MYC-tagged PF-8 by using the Gateway technology (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The KSHV ORF49 construct was generated in the pCMV2-FLAG vector by conventional PCR cloning with the ORF49 primers K49-F (5′-CCGGAATTCTACAATGACATCGAGAAGGCC-3′) and K49-R (5′-CGCGGATCCGACAAGGTAAAGATCGACCT-3′). Clones were verified by conventional sequencing. A PARP-1 expression construct (pCMV5-PARP-1) was a kind gift from W. Lee Kraus at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX, USA).

Transfection and transduction.

Polyethylenimine (1 mg/ml; Sigma) was used for the transfection of HEK293T cells, as previously described (19). To obtain PF-8-expressing lentiviruses, a FLAG-tagged PF-8-containing lentiviral vector and packaging vector (kind gifts from Seungmin Hwang, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA) were cotransfected into HEK293T cells. For transduction, the supernatants were then incubated with BC-3 cells, and the medium was replenished every 24 h for 3 days.

Construction of PF-80-knocked-down BC-3 cells.

A pLKO.1 TRC cloning vector (catalog number 10878) and scrambled small-hairpin RNA (shRNA) construct (catalog number 1864) were purchased from Addgene (20). To construct a PF-8 knockdown plasmid, a forward-strand primer (5′-CCGGTTTGGCACTCCAACGAAATATCTCGAGATATTTCGTTGGAGTGCCAAATTTTTG-3′) and a reverse-strand primer (5′-AATTCAAAAATTTGGCACTCCAACGAAATATCTCGAGATATTTCGTTGGAGTGCCAAA-3′) were annealed and transferred into the pLKO.1 TRC cloning vector using AgeI and EcoRI sites according to the TRC cloning protocol. The cloned shRNA expression cassette was verified by sequencing. BC-3 cells were transduced with shPF-8 or shRNA lentivirus as described above. The transduced cells were selected using 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma).

Luciferase reporter assays.

The luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to measure the promoter activity (pGL3-PAN-luc and pGL3-kRp-luc) (21, 22). HEK293T cells were transfected with a reporter construct, a KSHV RTA expression plasmid, an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression plasmid, and a PF-8 expression plasmid. Twenty-four hours posttransfection (hpt), cells were harvested and analyzed for the luciferase reporter assays according to the manufacturer's instructions. To test the effects of pharmacological drugs on the promoter activity, HEK293T cells were transfected as described above for 24 h, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated with fresh medium containing 1 μM MG132 (Sigma), 20 μM hydroxyurea (HU; Sigma), or 1 μM nicotinamide (NA; Sigma). Twenty-four hours posttreatment, the cells were harvested and analyzed by a luciferase reporter assay. Each transfection was performed in triplicate, with EGFP used as an internal control.

RT-qPCR.

Total RNA from the cells was extracted using the Tri reagent (MRC, Cincinnati, OH, USA), and cDNAs were synthesized using a RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with random hexamers. Transcripts were quantified with a Rotor-Gene quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) detection system (Qiagen) by using primers for PF-8 (forward, 5′-CTCCCTCGGCAGACACAGAT-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCGTGGTGCACACCGACGCCC-3′) and RTA (forward, 5′-GTGGCAATGAGGATGACTTGTTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TAGTGGTGGTCGGAGATTCGTA-3′) (23) and normalized to those for actin (forward, 5′-GTATCCTGACCCTGAAGTACC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGAAGGTCTCAAACATGATCT-3′). SYBR green PCR was run at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s, and a melting curve analysis was performed.

Western blot analysis.

For Western blot analysis, cells were harvested in a buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, and 0.025% bromophenol blue. The whole-cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, and probed with primary antibodies against FLAG-M2 (1:2,000), MYC (1:2,000), hemagglutinin (HA; 1:500), KSHV RTA (1:500), MHV-68 ORF45 (1:500), MHV-68 M9 (1:500), PARP-1 (1:1,000), PAR (1:1,000), and α-tubulin (1:2,000). Goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxide secondary antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) with Western blotting detection reagents (ELPIS, Republic of Korea) and analyzed using LAS-4000, a chemiluminescent image analyzer (Fujifilm). The band intensities were calculated by using the ImageJ program (35).

IP assay.

HEK293T cells were seeded and transfected with the plasmids indicated above for 48 h. BC-3 cells or HEK293T cells expressing PF-8 were resuspended in the immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, and 1% Triton X-100) containing 1/100 volume of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (19), and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting.

Immunofluorescence assay.

HEK293T cells were seeded onto a cover glass in a 24-well plate. Transfected cells were fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.15% picric acid in PBS. The blocking step was performed with 10% normal goat serum, with 1× PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Anti-FLAG and anti-PARP-1 (1:500) antibodies were incubated for 16 h at 4°C. Mouse-Cy3 and rabbit-Rho (1:2,000) were incubated for 45 min at room temperature. 4′,6-Diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain (1:1,000) was used for nuclear staining. The fluorescence images were obtained at a magnification of ×1,000 by using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 5 Exciter; Zeiss).

RESULTS

KSHV reactivation induces PARP-1 downregulation.

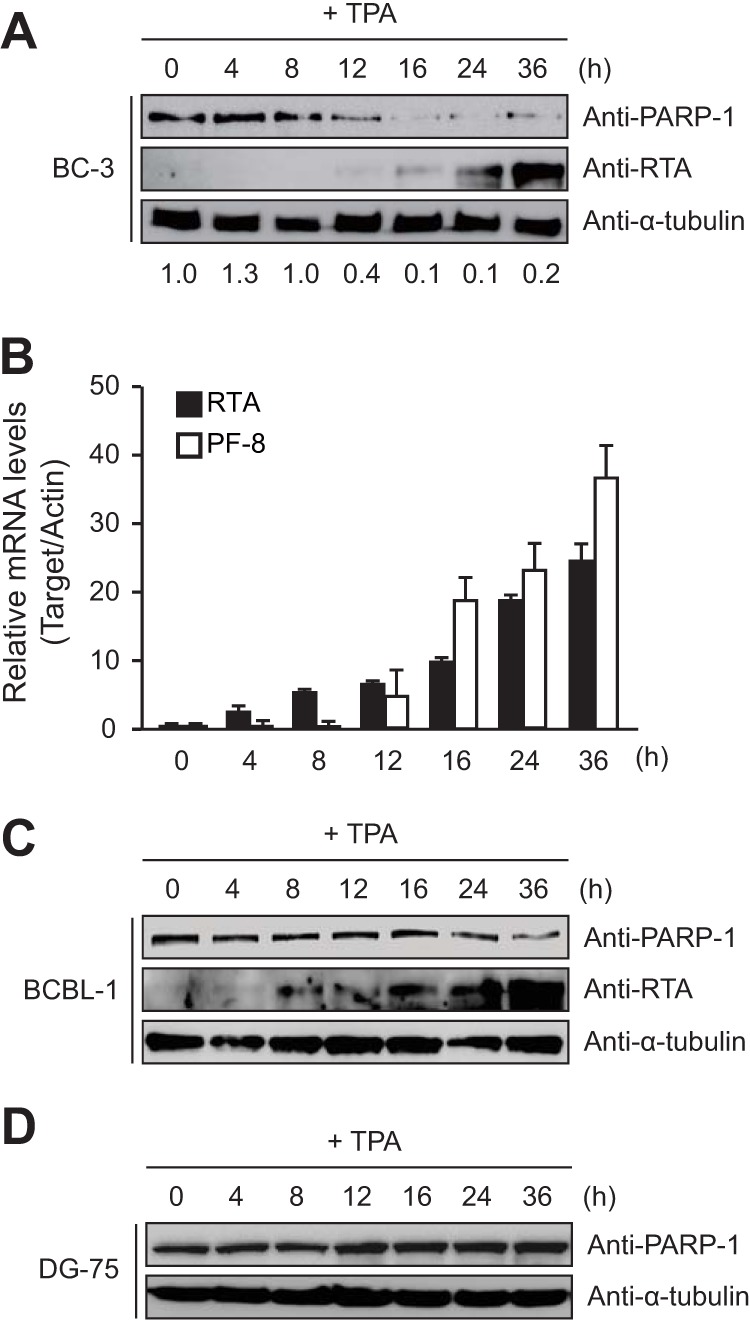

First, we examined the regulation of PARP-1 expression during lytic virus replication. When BC-3 and BCBL-1 cells latently infected with KSHV were treated with TPA, PARP-1 levels decreased over time, while expression of lytic genes, such as RTA and viral processivity factor 8 (PF-8), increased (Fig. 1A to C). Interestingly, PARP-1 began to disappear around the same time as PF-8 started to be expressed (Fig. 1B). There was no alteration of PARP-1 levels in virus-negative DG-75 cells treated with TPA (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that KSHV downregulates PARP-1 upon reactivation.

FIG 1.

The lytic replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) decreases poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) expression. KSHV-positive BC-3 (A, B) and BCBL-1 (C) cells and KSHV-negative DG-75 cells (D) were treated with 20 ng/ml of TPA and harvested at the indicated time points. The cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against PARP-1, RTA, and α-tubulin (A, C, and D) as well as by RT-qPCR for RTA and PF-8 transcripts (B). Ratios of the levels of expression of PARP-1 to α-tubulin are indicated.

PF-8 was sufficient to induce PARP-1 downregulation.

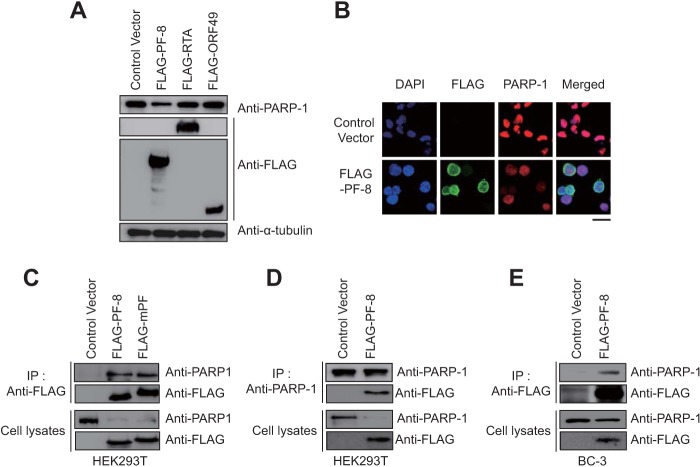

In addition to RTA and ORF49, ORF59 was shown to interact with PARP-1 in a genome-wide yeast two-hybrid screen of MHV-68 (8, 11, 24), although this interaction has not been validated in mammalian cells. KSHV ORF59 encodes PF-8, which is essential for virus genome replication (13–15, 25) as an early late protein (26, 27). To test whether these PARP-1-interacting proteins may induce PARP-1 downregulation, we transiently overexpressed KSHV RTA (22), ORF49, and PF-8 in HEK293T cells (19). The results showed that endogenous PARP-1 was downregulated in cells transfected with PF-8 but not in cells transfected with RTA or ORF49 (Fig. 2A). Immunofluorescence assays further confirmed the downregulation of PARP-1 in PF-8-expressing HEK293T cells (Fig. 2B). Initially, PF-8 was tested as a candidate in our study since its homologue in MHV-68 (mPF) was suggested to interact with PARP-1 (24). Immunoprecipitation (IP) analysis confirmed that KSHV PF-8 as well as MHV-68 mPF interacted with endogenous PARP-1 in transiently transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 2C). Reciprocal IP assays using anti-PARP-1 yielded consistent results (Fig. 2D). The association of PF-8 with endogenous PARP-1 was further confirmed in BC-3 cells stably expressing PF-8 using a lentivirus transduction system (Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

KSHV viral processivity factor 8 (PF-8) downregulates PARP-1 via direct interaction. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with a construct for KSHV RTA, ORF49, or PF-8. Transfected cells were harvested at 24 h posttransfection (hpt) and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PARP-1, anti-FLAG-M2, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs, fixed at 24 hpt, and immunostained with anti-FLAG-M2 and anti-PARP-1 antibodies. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The samples were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM 5 Exciter; Zeiss). Scale bar, 20 μm. (C and D) PF-8- and MHV-68 viral processivity factor (mPF)-expressing constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells and incubated for 48 h. Cells were harvested and analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation assay using anti-FLAG-M2 (C) or anti-PARP-1 (D) antibodies. (E) BC-3 cells were transduced with a lentivirus expressing FLAG-PF-8. After transduction, cells were harvested and analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation assay using anti-FLAG-M2 antibody.

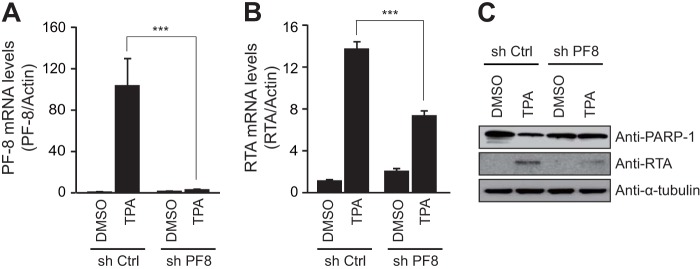

PF-8 was necessary to decrease the PARP-1 levels, facilitating the lytic replication of KSHV.

To confirm whether PF-8 is necessary to induce PARP-1 degradation, PF-8 knockdown BC-3 cells were generated by transducing cells with a lentivirus that expressed short-hairpin RNA interference RNAs (shRNAs) for PF-8 (shPF8) or scrambled sequences (short-hairpin control [shCtrl]). Upon KSHV reactivation, PF-8 knockdown was confirmed in shPF8 cells at the transcript levels (Fig. 3A). The levels of the RTA transcript and protein were lower in shPF-8 cells than those in shCtrl cells (Fig. 3B and C). Furthermore, PF-8 knockdown in BC-3 cells failed to cause PARP-1 downregulation (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that PF-8 is necessary to induce PARP-1 degradation, thereby facilitating the lytic replication of the virus.

FIG 3.

PF-8 knockdown reduced PARP-1 degradation as well as KSHV replication in BC-3 cells. PF-8 knockdown and control BC-3 cells were generated by a lentivirus expressing PF-8 and control shRNA, respectively. Expression levels of PF-8 (A) and RTA (B) transcripts were confirmed by RT-qPCR following TPA treatment for 24 h. (C) The cell lysates of shCtrl and shPF-8 cells were harvested and subjected to Western blotting using antibodies against PARP-1, RTA, and α-tubulin. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test (*** denotes a P value of <0.005). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

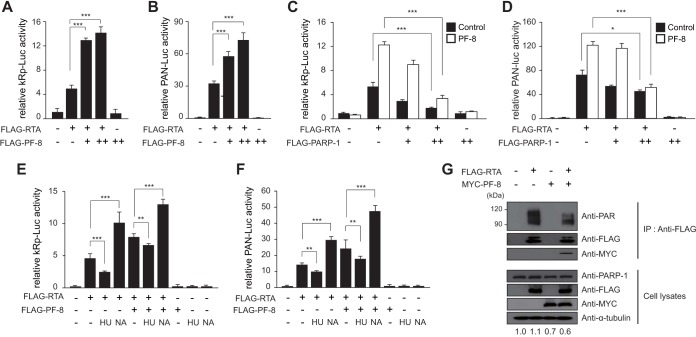

PF-8 enhances RTA-mediated transactivation via PARP-1 degradation.

Since PARP-1 represses RTA-mediated transactivation by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ating (PARylating) RTA (8), PARP-1 downregulation by PF-8 may enhance the RTA transactivation activity. In reporter assays using RTA (kRp-luc) and polyadenylated nuclear (PAN) RNA (pPAN RRE-luc) promoters (21, 22), PF-8 promoted RTA-mediated transactivation in a dose-dependent manner, while PF-8 alone did not induce any transactivation (Fig. 4A and B). To test whether this is due to PARP-1 degradation induced by PF-8, we cotransfected a PARP-1 expression plasmid and found that PARP-1 overexpression alleviated the PF-8 effect on RTA-mediated transactivation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C and D). Furthermore, pharmacological modulation of the PARP-1 activity using a PARP-1 activator (hydroxyurea [HU]) and a PARP-1 inhibitor (nicotinamide [NA]) led to a decrease and an increase of PF-8 effects on RTA, respectively (Fig. 4E and F). Lastly, to investigate the effect of PARP-1 degradation by PF-8 on RTA protein, we examined the levels of PARylated RTA proteins using anti-PAR antibody in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with RTA and PF-8 (Fig. 4G). When PF-8 was expressed, the level of PARylated RTA was lower than in the control, as the PARP-1 protein was degraded by PF-8. Direct interaction of PF-8 with RTA was also observed. Taken together, these results indicate that PF-8 increases the RTA transactivation activity by inhibiting the PARylation of RTA via promoting PARP-1 degradation.

FIG 4.

PF-8 increases RTA transactivation activity via targeting PARP-1. (A and B) HEK293T cells were transfected with the reporter construct pGL3-kRp-luc (A) or pGL3-PAN RRE-luc (B) (300 ng) and PF-8 (0, 50, and 125 ng) in the presence or absence of RTA-expressing plasmid (25 ng). (C and D) HEK293T cells were transfected with the reporter construct pGL3-kRp-luc (C) or pGL3-PAN RRE-luc (D) (300 ng), RTA-expressing plasmid (25 ng), and PARP-1-expressing plasmid (0, 50, and 150 ng) in the presence (open bars) or absence (filled bar) of PF-8 (125 ng). (E and F) HEK293T cells were transfected with the reporter construct pGL3-kRp-luc (E) or pGL3-PAN RRE-luc (F) (300 ng), PF-8 (125 ng), and RTA-expressing plasmid (25 ng). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were treated with 20 μM hydroxyurea (HU; a PARP-1 activator) or 1 μM nicotinamide (NA; a PARP-1 inhibitor) in fresh medium for another 24 h. The cells were harvested for luciferase reporter assays. Each transfection was performed in triplicate, with EGFP-expressing plasmid included as an internal control. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test (* denotes a P value of <0.05, ** denotes a P value of <0.01, and *** denotes a P value of <0.005). (G) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with PF-8- and RTA-expressing constructs and incubated for 48 h. Cells were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation assays using anti-FLAG-M2 antibody, followed by immunoblotting using anti-PAR, anti-PARP-1, anti-FLAG-M2, anti-MYC, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies.

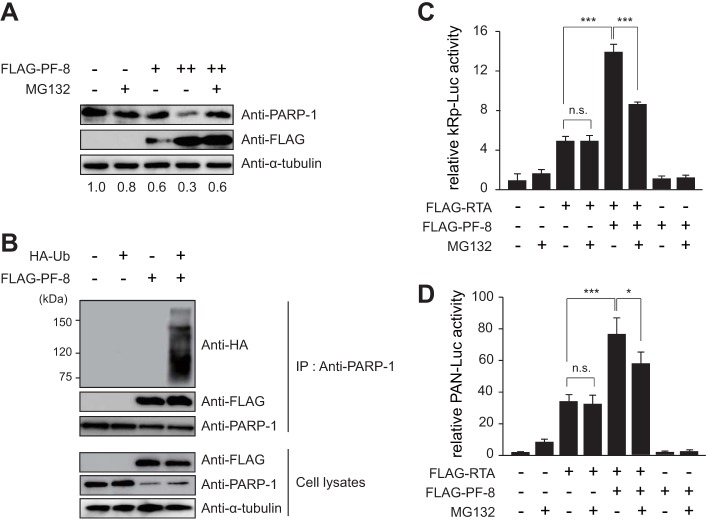

PF-8 degrades PARP-1 in a proteasome-dependent way.

Several studies have reported the association of proteasome activity with PARP-1 degradation (28–30). To investigate whether PF-8 induces the degradation of PARP-1 in a proteasome-dependent manner, HEK293T cells transfected with increasing amounts of PF-8 for 18 h were treated with the 26S proteasome subunit inhibitor MG132 (1 μM) (31) (Fig. 5A). PF-8 transfection decreased PARP-1 levels in a dose-dependent manner, but MG132 treatment inhibited this effect. Furthermore, when HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin and PF-8 and subjected to IP using a PARP-1 antibody, PF-8 increased the polyubiquitination of endogenous PARP-1 (Fig. 5B). MG132 treatment diminished RTA-mediated transactivation by PF-8, showing that this is also proteasome dependent (Fig. 5C and D). These results suggest that PF-8 induces PARP-1 degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which may contribute to the upregulation of RTA activity.

FIG 5.

PF-8 downregulates PARP-1 and enhances RTA-mediated transactivation in a proteasome-dependent manner. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with PF-8. Eighteen hours posttransfection, media were changed and cells were treated with 1 μM MG132 for 6 h. After treatment, protein expression in the cells was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PARP-1, anti-FLAG-M2, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. The ratios of the levels of expression of PARP-1 to α-tubulin are indicated. (B) PF-8- and HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub)-expressing constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells, and the cells were incubated for 48 h. They were then harvested and analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation assay using anti-PARP-1 antibody. (C and D) HEK293T cells were transfected with the reporter construct pGL3-kRp (C) or pGL3-PAN RRE (D) and PF-8 in the presence or absence of an RTA-expressing plasmid. Each transfection was performed in triplicate, with an EGFP-expressing plasmid included as an internal control. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were treated with 1 μM MG132 in fresh medium for a further 24 h. Cells were then harvested and analyzed by luciferase reporter assay. (*, P value < 0.05; ***, P value < 0.005; n.s., not statistically significant by Student's t test).

MHV-68 viral processivity factor (mPF) induced PARP-1 degradation during lytic replication.

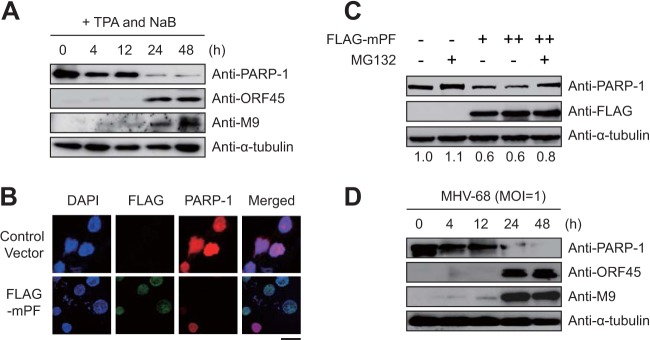

Consistently with the finding for KSHV, PARP-1 was downregulated upon reactivation in S11 cells harboring latent MHV-68 (Fig. 6A). To examine whether PARP-1 degradation by a viral processivity factor was conserved among gammaherpesviruses, Western blot and immunofluorescence assays were performed with HEK293T cells transiently transfected with MHV-68 mPF (24) (Fig. 6B and C). The results indicated that mPF was sufficient to degrade PARP-1 in a dose-dependent manner; induction of PARP-1 degradation was proteasome dependent, as PARP-1 levels were recovered by MG132 treatment (Fig. 6C). Moreover, de novo infection of MHV-68 downregulated PARP-1 in BHK-21 cells (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these results suggest that lytic replication of gammaherpesvirus induces PARP-1 downregulation via a physical interaction between PARP-1 and viral processivity factors in a proteasome-dependent manner.

FIG 6.

mPF-induced PARP-1 degradation during lytic replication. (A) S11 cells (latently MHV-68-infected B cells) were treated with 20 ng/ml TPA and 3 mM sodium butyrate (NaB). Cell lysates were harvested at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PARP-1, anti-ORF45, anti-M9, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with mPF. At 24 hpt, cells were fixed, immunostained, and examined under a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with mPF. At 18 hpt, medium was changed and cells were treated with 1 μM MG132 for 6 h. After treatment, protein expression in the cells was analyzed by Western blotting as described in the text. The ratio of the levels of expression of PARP-1 to α-tubulin are indicated. (D) BHK-21 cells were infected with MHV-68 at a multiplicity of infection of 1. After virus infection, the cell lysates were harvested at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PARP-1, anti-ORF45, anti-M9, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies.

DISCUSSION

PARP-1 has diverse functions, including DNA repair, cell cycle control, apoptosis, and gene expression (5–7, 32). In addition, PARP-1 has been shown to inhibit the lytic replication of KSHV and MHV-68 (8–10, 12, 33). In contrast, previous studies also report another role of PARP-1 in KSHV replication. Ohsaki et al. showed PARP-1 binding to terminal repeats of the KSHV genome and modulation of KSHV replication in latency (9), while Wang et al. showed a positive role for PARP-1 in KSHV genome replication (12). Although these functions of PARP-1 in KSHV infection are seemingly inconsistent with our and previous findings (8–10, 12, 33), the overall effects of PARP-1 on virus infection may still be inhibitory, especially in virion production, such as with viral protein expression, capsid assembly, and virion maturation, as Wang et al. showed that lowering the PARP-1 activity increased virion production (12). We found that KSHV and MHV-68 actively downregulated PARP-1 during lytic replication (Fig. 1 and 6), suggesting that these viruses have evolved strategies to overcome PARP-1 inhibition. We previously reported that MHV-68 ORF49 disrupts the interaction of RTA and PARP-1, thereby derepressing RTA activity. Here, we show another viral strategy, namely, that the viral processivity factors KSHV and MHV-68 ORF59 can also alleviate PARP-1-mediated inhibition by regulating PARP-1's stability.

KSHV ORF59 encodes viral processivity factor 8 (PF-8), which assists viral DNA polymerase with DNA processivity activity and plays an essential role in virus genome replication (13–15). PF-8 expression and function are RTA dependent in forming the replication complex (13–15, 25–27), while PF-8's activity and expression are regulated by a viral kinase (ORF36) and ORF57, respectively (16–18). In addition, PF-8 interacts with Ku70 and Ku86, impairing nonhomologous end joining during lytic replication (34). In this study, our results suggest a novel function of PF-8 in that PF-8 directly interacts with endogenous PARP-1, induces the degradation of PARP-1 in an ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent manner, and further activates RTA-mediated transactivation, leading to increased viral replication. This effect of PF-8 was dependent on PARP-1, as shown from PARP-1 overexpression as well as the pharmacological modulation of PARP-1's activity (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the effects of HU treatment were marginal on PF-8 enhancement of the RTA activity compared with those of NA treatment, suggesting that further activation of already-degraded PARP-1 protein was not as effective as its inhibition. Despite the fact that PF-8 is a downstream gene of RTA, PF-8 knockdown BC-3 cells exhibited decreased RTA expression together with increased PARP-1 levels upon reactivation (Fig. 3) and PF-8 reduced PARylation of RTA, suggesting that PF-8 may contribute to sustained RTA activity during lytic replication.

Although our results show that PF-8 induces the proteasome-dependent degradation of PARP-1, detailed molecular mechanisms for this process are not yet known. Given that PF-8 increased the polyubiquitination of PARP-1 (Fig. 5), a cellular protein with Ub-E3 ligase activity may be recruited and promote PARP-1 degradation, although we cannot exclude the possibility of viral processivity factors with unexpected ubiquitin ligase activities. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that viral processivity factors induce PARP-1 downregulation in a proteasome-dependent manner during virus replication. This study highlights a novel mechanism by which viral processivity factors facilitate the lytic replication of gammaherpesvirus and suggests an intricate molecular feed-forward loop of virus replication between RTA and viral processivity factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2012R1A1A2004532 to M.J.S.).

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

[This article was published on 19 August 2015 with an alternate spelling of the first author's name in the byline. The byline was updated in the current version, posted on 27 April 2018.]

REFERENCES

- 1.Young LS, Rickinson AB. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer 4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damania B. 2004. Oncogenic γ-herpesviruses: comparison of viral proteins involved in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:656–668. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye F, Lei X, Gao S-J. 2011. Mechanisms of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency and reactivation. Adv Virol 2011:193860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H-R, Brulois K, Wong L, Jung JU. 2012. Modulation of immune system by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: lessons from viral evasion strategies. Front Microbiol 3:44. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko HL, Ren EC. 2012. Functional aspects of PARP1 in DNA repair and transcription. Biomolecules 2:524–548. doi: 10.3390/biom2040524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo X, Kraus WL. 2012. On PAR with PARP: cellular stress signaling through poly (ADP-ribose) and PARP-1. Genes Dev 26:417–432. doi: 10.1101/gad.183509.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson BA, Kraus WL. 2012. New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly (ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13:411–424. doi: 10.1038/nrm3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwack Y, Nakamura H, Lee SH, Souvlis J, Yustein JT, Gygi S, Kung H-J, Jung JU. 2003. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 and Ste20-like kinase hKFC act as transcriptional repressors for gamma-2 herpesvirus lytic replication. Mol Cell Biol 23:8282–8294. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8282-8294.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohsaki E, Ueda K, Sakakibara S, Do E, Yada K, Yamanishi K. 2004. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 binds to Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) terminal repeat sequence and modulates KSHV replication in latency. J Virol 78:9936–9946. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9936-9946.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko Y-C, Tsai W-H, Wang P-W, Wu I-L, Lin S-Y, Chen Y-L, Chen J-Y, Lin S-F. 2012. Suppressive regulation of KSHV RTA with O-GlcNAcylation. J Biomed Sci 19:12. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noh C-W, Cho H-J, Kang H-R, Jin HY, Lee S, Deng H, Wu T-T, Arumugaswami V, Sun R, Song MJ. 2012. The virion-associated open reading frame 49 of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 promotes viral replication both in vitro and in vivo as a derepressor of RTA. J Virol 86:1109–1118. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05785-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Li H, Tang Q, Maul GG, Yuan Y. 2008. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ori-Lyt-dependent DNA replication: involvement of host cellular factors. J Virol 82:2867–2882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01319-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan SR, Bloomer C, Chandran B. 1998. Identification and characterization of human herpesvirus-8 lytic cycle-associated ORF 59 protein and the encoding cDNA by monoclonal antibody. Virology 240:118–126. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin K, Dai CY, Ricciardi RP. 1998. Cloning and functional analysis of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus DNA polymerase and its processivity factor. J Virol 72:6228–6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan SR, Chandran B. 2000. Characterization of human herpesvirus 8 ORF59 protein (PF-8) and mapping of the processivity and viral DNA polymerase-interacting domains. J Virol 74:10920–10929. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.23.10920-10929.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossetto CC, Susilarini NK, Pari GS. 2011. Interaction of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF59 with oriLyt is dependent on binding with K-Rta. J Virol 85:3833–3841. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDowell ME, Purushothaman P, Rossetto CC, Pari GS, Verma SC. 2013. Phosphorylation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus processivity factor ORF59 by a viral kinase modulates its ability to associate with RTA and oriLyt. J Virol 87:8038–8052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03460-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majerciak V, Uranishi H, Kruhlak M, Pilkington GR, Massimelli MJ, Bear J, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK, Zheng ZM. 2011. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF57 interacts with cellular RNA export cofactors RBM15 and OTT3 to promote expression of viral ORF59. J Virol 85:1528–1540. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01709-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang H-R, Cheong W-C, Park J-E, Ryu S, Cho H-J, Youn H, Ahn J-H, Song MJ. 2014. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 encoding open reading frame 11 targets TANK binding kinase 1 to negatively regulate the host type I interferon response. J Virol 88:6832–6846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03460-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffat J, Grueneberg DA, Yang X, Kim SY, Kloepfer AM, Hinkle G, Piqani B, Eisenhaure TM, Luo B, Grenier JK, Carpenter AE, Foo SY, Stewart SA, Stockwell BR, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM, Root DE. 2006. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell 124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Chen S, Feng J, Deng H, Sun R. 2010. Myc is required for the maintenance of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. J Virol 84:8945–8948. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00244-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song MJ, Li X, Brown HJ, Sun R. 2002. Characterization of interactions between RTA and the promoter of polyadenylated nuclear RNA in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8. J Virol 76:5000–5013. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.5000-5013.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Zhou F, Ye F, Gao SJ. 2008. Genetic disruption of KSHV major latent nuclear antigen LANA enhances viral lytic transcriptional program. Virology 379:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Salwinski L, Zhang C, Chu D, Sampankanpanich C, Reyes NA, Vangeloff A, Xing F, Li X, Wu T-T. 2011. An integrated approach to elucidate the intra-viral and viral-cellular protein interaction networks of a gamma-herpesvirus. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002297. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AuCoin DP, Colletti KS, Cei SA, Papousková I, Tarrant M, Pari GS. 2004. Amplification of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 lytic origin of DNA replication is dependent upon a cis-acting AT-rich region and an ORF50 response element and the trans-acting factors ORF50 (K-Rta) and K8 (K-bZIP). Virology 318:542–555. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Guzman D, Rickabaugh T, Wu T-T, Brown H, Cole S, Song MJ, Tong L, Sun R. 2003. Transcription program of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 77:10488–10503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10488-10503.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virgin H, Latreille P, Wamsley P, Hallsworth K, Weck KE, Dal Canto AJ, Speck SH. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 71:5894–5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsushima S, Okita N, Oku M, Nagai W, Kobayashi M, Higami Y. 2011. An Mdm2 antagonist, Nutlin-3a, induces p53-dependent and proteasome-mediated poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase1 degradation in mouse fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 407:557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai W, Okita N, Matsumoto H, Okado H, Oku M, Higami Y. 2012. Reversible induction of PARP1 degradation by p53-inducible cis-imidazoline compounds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 421:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T, Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Smulson ME, Chock PB, Yang DC. 2008. Polyubiquitylation of PARP-1 through ubiquitin K48 is modulated by activated DNA, NAD+, and dipeptides. J Cell Biochem 104:318–328. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuliano M, D'Anneo A, De Blasio A, Vento R, Tesoriere G. 2003. Apoptosis meets proteasome, an invaluable therapeutic target of anticancer drugs. Ital J Biochem 52:112–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakondi E, Catalgol B, Bak I, Jung T, Bozaykut P, Bayramicli M, Ozer NK, Grune T. 2011. Age-related loss of stress-induced nuclear proteasome activation is due to low PARP-1 activity. Free Radic Biol Med 50:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Si H, Verma SC, Robertson ES. 2006. Proteomic analysis of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus terminal repeat element binding proteins. J Virol 80:9017–9030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00297-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao Y, Chen J, Liao Q, Wu Y, Peng C, Chen X. 2013. Lytic infection of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus induces DNA double-strand breaks and impairs non-homologous end joining. J Gen Virol 94:1870–1875. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.053033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasband WS. 2014. ImageJ. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/. [Google Scholar]