ABSTRACT

Plasma microRNAs (miRNAs) change in abundance in response to disease and have been associated with liver fibrosis severity in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. However, the early dynamics of miRNA release during acute HCV infection are poorly understood. In addition, circulating miRNA signatures have been difficult to reproduce among separate populations. We studied plasma miRNA abundance during acute HCV infection to identify an miRNA signature of early infection. We measured 754 plasma miRNAs by quantitative PCR array in a discovery cohort of 22 individuals before and during acute HCV infection and after spontaneous resolution (n = 11) or persistence (n = 11) to identify a plasma miRNA signature. The discovery cohort derived from the Baltimore Before and After Acute Study of Hepatitis. During acute HCV infection, increases in miR-122 (P < 0.01) and miR-885-5p (Pcorrected < 0.05) and a decrease in miR-494 (Pcorrected < 0.05) were observed at the earliest time points after virus detection. Changes in miR-122 and miR-885-5p were sustained in persistent (P < 0.001) but not resolved HCV infection. The circulating miRNA signature of acute HCV infection was confirmed in a separate validation cohort that was derived from the San Francisco-based You Find Out (UFO) Study (n = 28). As further confirmation, cellular changes of signature miRNAs were examined in a tissue culture model of HCV in hepatoma cells: HCV infection induced extracellular release of miR-122 and miR-885-5p despite unperturbed intracellular levels. In contrast, miR-494 accumulated intracellularly (P < 0.05). Collectively, these data are inconsistent with necrolytic release of hepatocyte miRNAs into the plasma during acute HCV infection of humans.

IMPORTANCE MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNA molecules that emerging research shows can transmit regulatory signals between cells in health and disease. HCV infects 2% of humans worldwide, and chronic HCV infection is a major cause of severe liver disease. We profiled plasma miRNAs in injection drug users before, during, and (in the people with resolution) after HCV infection. We discovered miRNA signatures of acute and persistent viremia and confirmed these findings two ways: (i) in a separate cohort of people with newly acquired HCV infection and (ii) in an HCV cell culture system. Our results demonstrate that acute HCV infection induces early changes in the abundance of specific plasma miRNAs that may affect the host response to HCV infection.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a single-stranded positive-sense hepatotropic RNA virus that infects over 170 million people worldwide. Acute HCV infection progresses to chronic infection in ∼75% of cases (1–3). Little is understood about early host-pathogen interactions due to a lack of representative animal models and the difficulty in studying acute HCV, which is largely asymptomatic.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are 18- to 25-nucleotide noncoding RNA molecules with widespread gene network regulatory capacity. miRNAs are readily detectable in cell-free components of blood, and circulating extracellular miRNAs have been associated with the severity and progression of numerous human diseases, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (4, 5), liver injury (6), colorectal cancer (7), and cardiac injury (8). Little is understood about the early dynamics and release of circulating miRNAs under specific disease conditions. Importantly, circulating miRNA signatures have been challenging to confirm in separate cohorts, raising questions as to whether consistent changes in circulating miRNAs occur (9, 10).

miRNAs have profound intracellular effects and have been described to play a role in viral pathogenesis (11, 12). Indeed, HCV replication requires the hepatocyte-specific miRNA miR-122 for efficient replication (13), and an miR-122 antagonist was shown to have potent antiviral effects in a human trial (14). Whereas conventional wisdom predicts that extracellular miRNAs found circulating in the plasma are the result of cell lysis, extracellular miRNAs have been shown to be selectively secreted by donor cells and can regulate genes in target cells in animal and tissue culture models (15–25). We hypothesized that acute HCV infection leads to regulated changes in the abundance of circulating microRNAs. We used multiple approaches to validate the circulating miRNA signature.

(Portions of these data were presented as an oral abstract at the Annual Liver Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [October 2013 in Washington, DC]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

The principal measurements in this study were performed using samples from a discovery cohort. Major findings were confirmed in a separate validation cohort. The discovery cohort was composed of 22 participants in the Baltimore Before and After Acute Study of Hepatitis (BBAASH) cohort, an ongoing study of injection drug users (IDU) who are at high risk for acquiring HCV infection (2). Eligible participants have a history of injection drug use and are negative for anti-HCV antibodies and HCV RNA at the time of enrollment. All enrollees are assessed for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HIV status at enrollment, vaccinated for HBV if there is no evidence of previous vaccination, and monitored regularly for seroconversion at regular intervals as previously described. Written consent is obtained from each participant. Once enrolled, participants receive counseling to reduce drug use and its complications. Phlebotomy is performed monthly, as previously described (2). Participant infection status is monitored by quantitative PCR (qPCR) for HCV RNA, and those with acute HCV infection are referred for evaluation for treatment. The validation cohort was composed of 28 participants in the San Francisco-based You Find Out (UFO) Study, a prospective study of young IDUs at high risk for acquiring HCV infection in whom incident acute HCV infection is identified and monitored monthly (26). Written consent was obtained from each participant. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine approved the BBAASH study, and the IRB of the University of California at San Francisco approved the UFO study.

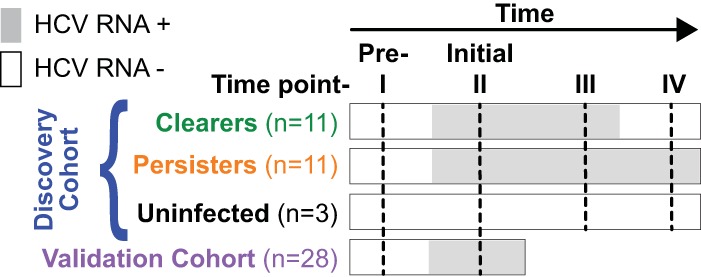

Sample selection.

Plasma samples were selected from participants for whom acute HCV infection and its outcome were fully documented. Four samples were examined over structured time intervals for each participant in the discovery cohort (Fig. 1): time I is previremia, defined by negative HCV RNA and anti-HCV antibody; time II is initial viremia, defined by the first positive HCV RNA test; time III is late acute infection, defined by the last available viremic plasma sample from persons who cleared infection (clearers) and a time-from-initial-viremia-matched sample from persons with persistent infection (persisters); and time IV is postviremia, defined by HCV RNA-negative values on ≥2 consecutive visits more than 4 weeks apart in clearers and a time-from-initial-viremia-matched sample in persisters. An additional 3 participants from the BBAASH study were included as negative controls. The negative-control participants were injection drug users in whom HCV infection was never detected, and plasma samples were examined that corresponded to the same structured time intervals as that used for the discovery cohort to control for the natural variation in abundance of miRNAs over time. For confirmation of the principal findings, two samples were selected from each of the 28 individuals in the validation cohort: time I, previremia, is defined by negative HCV RNA and anti-HCV antibody, and time II, initial viremia, defined by the first HCV RNA-positive sample within 8 months of incident HCV infection.

FIG 1.

Study design. miRNAs were quantified in plasma samples from injection drug users in the discovery cohort who acquired acute HCV infection and either cleared infection (clearers; n = 11) or developed persistent infection (persisters; n = 11). miRNAs also were quantified in plasma samples from 3 participants in the discovery cohort who did not develop infection and who had available samples at time intervals that closely matched the intervals in the acutely infected participants. A separate validation cohort (n = 28) was studied to confirm the findings in the discovery cohort.

HCV RNA quantification.

HCV RNA levels in plasma samples were previously quantified using a commercial reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) assay (TaqMan HCV analyte-specific reagent; Roche Molecular Diagnostics, USA), which has a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 50 IU/ml. Samples with detectable HCV RNA that were below the LLOQ were assigned a value of 25 IU/ml, and detection was confirmed using a nested PCR for the Core-E1 region of HCV as previously published (27).

miRNA isolation and quantification.

RNA was isolated from 100 μl of plasma according to the miRvana total RNA isolation protocol for plasma samples (Life Technologies). Prior to isolation, 5 ng of glycogen was added as a carrier polymer as previously described (28), and 0.5 pg of Arabidopsis thaliana miRNA ath-miR-159a (UUUGGAUUGAAGGGAGCUCUA; Integrated DNA Technologies) was added as an extraction control.

After extraction, RT-qPCR-based TaqMan OpenArray chips were used to quantify 754 miRNAs using a human microRNA panel (Pool A v2.1 and Pool B v3.0) on the QuantStudio 12K Flex machine (Life Technologies) at the Genetic Resources Core Facility, Johns Hopkins Institute of Genetic Medicine, Baltimore, MD. CT values from the QuantStudio machine that did not exceed 35 (the array-wide validated limit of quantitation) were exported using ExpressionSuite (Life Technologies) software. Quantile normalization for arrayed data was performed as has been previously described using the limma package, version 3.24.3, in R (www.r-project.org), version 3.1.2 (29–31).

The qPCR array was separately validated by performing individual RT-qPCR assays in duplicate for ath-miR-159a, miR-122, and miR-885-5p using the microRNA TaqMan assay. Fold change values between longitudinal samples were computed using the 2ΔΔCT method (where CT is threshold cycle) against ath-miR-159a and by using the 2ΔCT method in the quantile-normalized approach, with agreement between the two methods for all miRNAs for which results are presented. Quantile-normalized data are presented.

In vitro HCV infection.

A serum-free preparation of the J6/JFH-1 infectious clone of HCV (HCVcc) was produced by isolating serum-free supernatants from cells that were transfected with HCV RNA. Briefly, the pUC19-J6/JFH1 plasmid was linearized using XbaI (New England BioLabs), and RNA was synthesized in vitro using the T7-polymerase based RiboMAX kit (Promega). Phenol-chloroform-purified RNA was transfected into Huh 7.5.1 cells using DMRIE-C reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum until 24 h posttransfection. Serum-containing medium was removed at 24 h, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice, and medium was replaced with Ultraculture serum-free media (BioWhittaker). Serum-free supernatants from infected cells were collected 5 days posttransfection, centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min, and passed through a 0.22-μm filter to remove cellular debris. HCV RNA was quantified using the protocol described above. Mock virus preparations were produced using the same protocol, except no HCV RNA was added to the DMRIE-C transfection.

Serum-free cultured Huh 7.5.1 cells were infected with the serum-free HCVcc preparation at a multiplicity of infection of 5 IU/cell. Supernatants were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min and passed through a 0.22-μm filter to remove cellular debris. Supernatant and cellular miRNAs were isolated using the miRvana PARIS and miRNA isolation systems, respectively (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

In vitro HCV infection with miRNA inhibition and overexpression.

Seed cultures of Huh 7.5.1 cells were transfected with microRNA miRvana mimics and inhibitors (Life Technologies) at a final concentration of 40 nM using Oligofectamine (Life Technologies). Two days after transfection, cells were infected with HCVcc at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 IU/cell. HCV RNA was quantitated 48 h after infection in supernatants and after cell lysis. Immunohistochemistry for HCV also was performed 48 h after infection. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min and then stained for HCV using the 9E10 anti-NS5A antibody (32) at a 1:500 dilution in PBS with 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with PBS and stained using secondary antibody fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies) at a 1:1,000 dilution in PBS with 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed twice in PBS and then imaged with a Zeiss inverted microscope with an Olympus camera.

Focus-counting analysis.

Cells were transfected, fixed, and stained as described above, except that infection was performed using an MOI of 4 IU/cell to facilitate focus counting. Images were acquired and foci were counted using an AID iSpot Reader Spectrum, operating AID ELISpot Reader, version 7.0, at the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center Immunology Core, Baltimore, MD.

Statistical analysis.

To avoid false discovery due to incomplete coverage, only microRNAs that were detected at a frequency of greater than 70% across all samples were selected for analysis (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). Two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed when appropriate. Pearson's correlation was used to detect associations between continuous variables. Multiple-comparison correction was performed according to the Benjamini-Hochberg method (33). Ten microRNAs (including miR-122, miR-885-5p, and let-7b) were prespecified before analysis for their relevance to HCV biology; correction for multiple comparisons was not employed for these microRNAs. Statistical analysis was performed using R, version 3.1.2.

Array data accession number.

Array data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession number GSE61187).

RESULTS

Study and array characteristics.

The median (interquartile range [IQR]) number of days of infection at initial viremia in the discovery cohort was 26 (17 to 46), the median (range) age was 25 years old (19 to 31), 20 (91%) were white, and 15 (68%) were female (Table 1). The median (IQR) HCV RNA level upon initial viremia was 6.3 log10 IU/ml (5.3 to 6.7) and the median (IQR) ALT was 41 U/liter (26 to 241). HCV genotype 1a was present in 16/22 (73%) participants, followed by genotype 1b in 2/22 (9%), genotype 2 in 1/22 (4.5%), and genotype 3 in 3/22 (13.6%). Although the discovery and validation cohorts both represent the natural history of acute HCV (34–37), the main differences between them were race and IFNL3 genotype: 18 (64%) of the validation cohort was white and only 10 (36%) were IFNL3 (rs12979860) genotype C/C. In addition, the median (IQR) imputed number of days infected in the discovery cohort was 26 (17 to 46) days, and it was 46 (39 to 96) days for the validation cohort (Table 1). None of the subjects included in either cohort had evidence of infection with HIV or HBV over the course of the sampling interval.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Value(s) forc: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery cohort (n = 22) | Validation cohort (n = 28) | Uninfected controls (n = 3) | |

| Age (yr),a median (min-max) | 25 (19–31) | 23 (16–28) | 29 (29–31) |

| White, n (%) | 20 (91) | 18 (64) | 2 (67) |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (68) | 10 (36) | 2 (67) |

| HCV genotype,a n (%) | |||

| 1a | 16 (73) | 11 (39) | — |

| 1b | 2 (9) | 2 (7) | — |

| 2 | 1 (5) | 5 (18) | — |

| 3a | 3 (14) | 10 (36) | — |

| IFNL3 (rs12979860) genotype, n (%) | |||

| C/C | 11 (50) | 10 (36) | NP |

| C/T | 9 (41) | 15 (54) | NP |

| T/T | 2 (9) | 3 (11) | NP |

| ALT (U/liter),a median (IQR) | 41 (26–241) | 38 (19–83.25) | NP |

| HCV RNA (log10 IU/ml),a median (IQR) | 6.3 (5.3–6.7) | 5.8 (4.97–7.22) | Undetectable |

| Days infected,a,b median (IQR) | 26 (17–46) | 46 (39–96) | — |

At initial viremia.

Imputed infection date is the midpoint between the last known aviremic and first known viremic dates.

NP, the measurement was not performed; —, not applicable; undetectable, all samples were below the lower limit of detection over the sampling interval.

A median (range) of 303 miRNAs (180 to 386) was detected per sample: 108 miRNAs were detectable in >98% of samples, and 468 miRNAs were detectable in ≤50% of samples. The analysis was limited to the 243 interpretable miRNAs that were detectable in greater than 70% of all samples. No significant differences were found in the number of miRNAs detected per sample, the unnormalized array median CT values, or the extraction efficiency of samples across the sampled time points (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

A circulating miRNA signature of acute HCV infection.

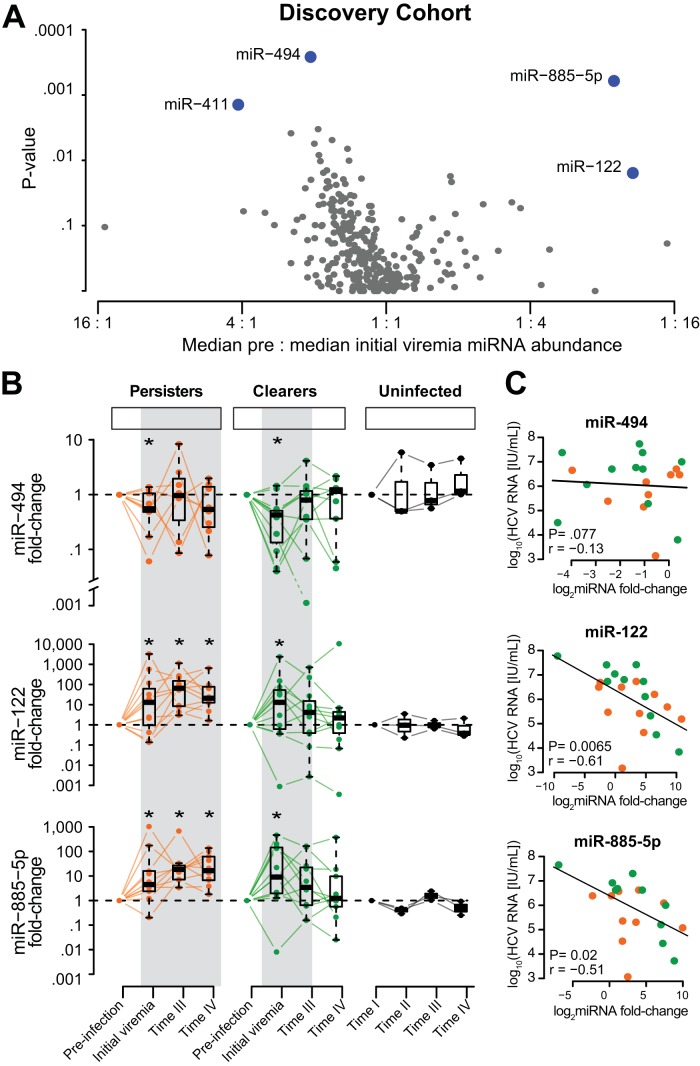

With the onset of viremia, the abundance of four plasma miRNAs significantly changed (Fig. 2A); the changes in abundance were not associated by their constitutive expression in liver. Extracellular circulating miR-494, the second most abundant miRNA in the liver, and miRNA-411 decreased to a median (IQR) of 0.48-fold (0.19 to 0.78) and 0.24-fold (0.15 to 0.61), respectively (Pcorrected < 0.05 for each), compared to preinfection levels; both miRNAs decreased in 15/22 (68%) participants. In contrast, circulating levels of miR-122, the most abundant miRNA in the liver, rose a median (IQR) value of 5.3-fold (1.5 to 39.2; P < 0.01) over preinfection levels, and increased levels were noted in 16/22 (73%) participants. miR-885-5p rose a median (IQR) value of 9.0-fold (2.4 to 130.2; P < 0.001), and increased levels were noted in 19/22 (86%) participants. We confirmed that amplification scores for miR-494, miR-411, miR-122, and miR-885-5p were above 1.2, the accepted threshold. In addition, the changes in abundance of miR-122 and miR-885-5p were individually confirmed using separate RT-qPCR assays and correlated tightly with the results from the qPCR array (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Acute HCV infection results in an increase in circulating miR-122 and miR-885-5p and a decrease in circulating miR-494. (A) A volcano plot depicts the median change in abundance of each miRNA across 22 participants between previremia and initial viremia on the x axis (miRNAs that are increased at initial viremia compared to the level at previremia are to the right of the graph). The y axis shows the uncorrected P value of the change in miRNA abundance. miRNAs in blue were significantly different between previremia and initial viremia in the discovery cohort after correction for multiple comparisons; however, no correction was applied for miR-122, which was prespecified in the study design for its relevance to HCV biology. (B) The change in circulating miRNA abundance versus preinfection in matched time intervals is displayed for BBAASH participants who were HCV negative (black) and who acquired acute HCV infection (green and orange lines). The selected time points were determined by participants who acquired HCV: before infection (preinfection), during acute infection in the earliest (initial viremia) and latest (time III) available samples, and either after infection in clearers (green; n = 11) or during the transition to chronic infection in persisters (orange; n = 11) (time IV). Shown are changes in miRNA abundance from the baseline in all 22 individuals in the discovery cohort for miR-411, miR-494, miR-122, and miR-885-5p. (C) The x axis shows the change in abundance of miR-494, miR-122, and miR-885-5p between preinfection and initial viremia. The y axis shows the contemporary plasma log10 HCV RNA levels (international units per milliliter) at initial viremia. Individual points are further delineated for clearers (green; n = 11) and persisters (orange; n = 11).

The extracellular miRNA signature was confirmed in a validation cohort of 28 participants in the San Francisco-based UFO study (Table 1). Changes in circulating miR-494, miR-122, and miR-885 with HCV infection were consistently observed in the validation cohort: miR-494 levels decreased a median (IQR) of 0.43-fold (0.19 to 1.7) (P < 0.05), miR-122 levels rose a median (IQR) of 2.3-fold (0.9 to 4.7) (P < 0.05), and miR-885-5p rose a median (IQR) of 1.5-fold (0.9 to 3.25) (P < 0.05). Changes in miR-411 were not consistently observed, so this miRNA was not studied further (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

To determine whether the extracellular miRNA signature of acute HCV infection persisted during HCV viremia, miRNA abundance was quantified until the resolution of infection (clearers) or until early chronic infection (persisters) (Fig. 2B). Four samples were taken from each person: (i) preinfection (negative HCV RNA and antibody tests); (ii) initial viremia (first positive HCV RNA test); (iii) time III (the last viremic visit in clearers and a time-from-initial-viremia-matched sample from persisters); and (iv) time IV (HCV RNA consistently negative on ≥2 consecutive visits more than 4 weeks apart in clearers and a time-from-initial-viremia-matched sample in persisters). miR-494 levels decreased transiently at initial viremia but were not significantly different from preinfection levels at later time points (Fig. 2B). In contrast, miR-122 and miR-885 levels were persistently elevated for the duration of viremia, returning to preinfection levels at time IV in clearers but remaining elevated in persisters (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). To verify that the extracellular miRNA signature was not the result of fluctuations over time that are unrelated to acute HCV infection, levels of miRNAs that constituted the signature also were examined in 3 IDUs in the BBAASH cohort who did not contract HCV over the course of their participation in the study. Plasma samples from uninfected IDUs were matched for intervals that were comparable with those observed in the discovery cohort (Fig. 1 and 2B). No consistent changes in abundance were noted over time for miR-494, miR-122, and miR-885-5p among the 3 uninfected IDUs, further underscoring the findings in acute HCV infection.

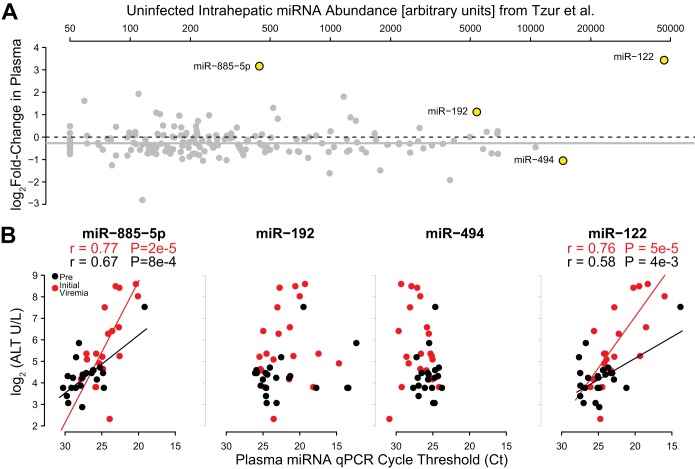

We further investigated whether there were predictors of the circulating miRNA signature, first by testing whether its components were related to contemporary HCV RNA levels. While we observed no relationship between HCV RNA levels and the change in abundance of miR-494, we found inverse associations with miR-122 (r = −0.56, P = 0.0065) and miR-885-5p (r = −0.5, P = 0.02) (Fig. 2C). These associations were observed only during the initial viremia time point. We next used two approaches to consider the role of hepatocyte damage in producing the extracellular miRNA signature. First, we adapted data from Tzur et al. describing the abundance of 185 miRNAs in human livers that also were profiled in our study (38). We found no relationship between intrahepatic abundance of miRNAs and their change in extracellular abundance upon acute HCV infection (r = −0.04, P = 0.46) (Fig. 3A). Similarly, we applied data from 148 miRNAs examined by Randall et al. to our study and did not detect a relationship between liver abundance and change in plasma abundance after accounting for miR-122 (r = −0.09, P = 0.28) (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) (39).

FIG 3.

Circulating microRNA signature of acute HCV infection does not reflect intrahepatic miRNA abundance. (A) The change in circulating miRNA abundance from pre- to initial viremia for each of 185 miRNAs (y axis) was compared to the intrahepatic abundance of the same miRNAs (x axis) based on previously published data (38). When miR-122, the most abundant intrahepatic miRNA, was included, there was a statistically significant but weak correlation between intrahepatic abundance and the change in circulating abundance of all studied miRNAs (r = 0.19; P = 0.001). The relationship was lost when miR-122 was excluded from the analysis (r = −0.04; P = 0.46). (B) The relative circulating abundances of miR-885-5p, miR-192, miR-494, and miR-122 were compared to contemporaneous ALT levels at previremia (black) and initial viremia (red) and are presented in order of their intrahepatic abundance. Regression lines and their corresponding Pearson's correlation coefficient are included for statistically significant associations.

The second approach we used to study the role of hepatocyte damage in the extracellular miRNA signature was to examine associations with aminotransferases: while miR-122 and miR-885 were associated with contemporaneous ALT levels, miR-494 had no association with ALT despite its reported intrahepatic abundance (Fig. 3A and B; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Conversely, miR-192, which has been reported as being increased and related to ALT levels in necrolytic drug-induced liver injury (40, 41), was not significantly elevated or associated with ALT levels in our study (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results suggest that changes in extracellular miRNA abundance are not solely the result of cell lysis.

miRNA signature of acute HCV infection in vitro.

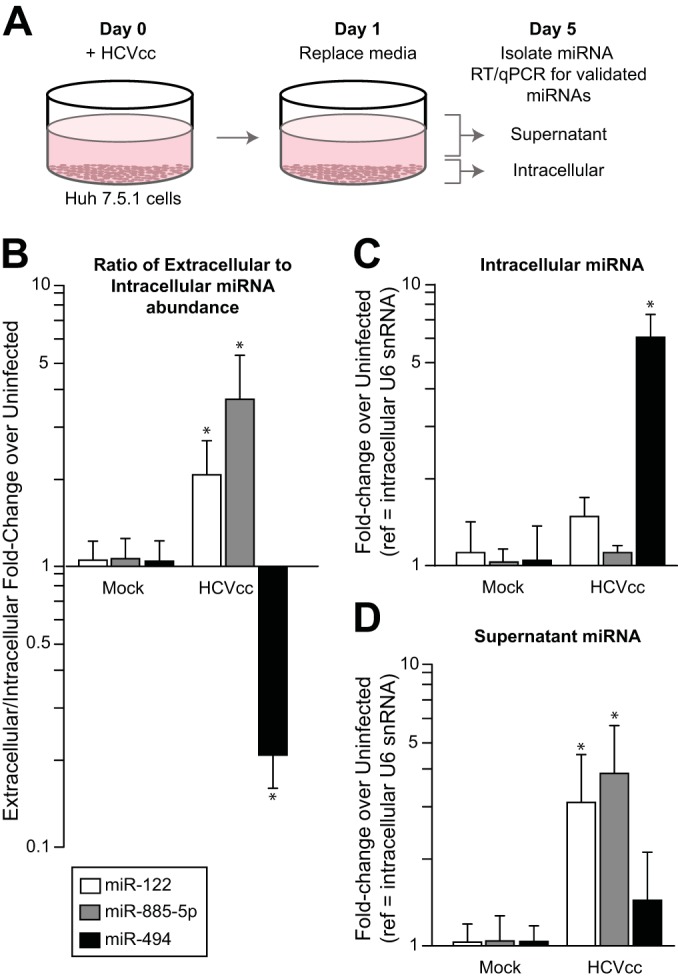

To support that hepatocytes, and not other cells, contribute to the miRNA signature of acute HCV infection, we infected Huh 7.5.1 hepatoma cells with HCVcc and quantified the expression of miRNAs in cells and supernatants, comparing these amounts to those of uninfected cells that were cultured for the same number of days (Fig. 4A). Quantities of extracellular miRNAs were normalized to intracellular amounts of the same miRNAs to control for cell death present in test and control wells. The extracellular signature that was found in circulating human plasma was confirmed in vitro: miR-122 and miR-885 abundance increased outside cells relative to inside, while that of miR-494 decreased (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, intracellular miR-122 and miR-885-5p abundance did not vary with infection (Fig. 4C), while extracellular levels significantly increased (P < 0.05 for both) (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the relative decrease in extracellular miR-494 abundance largely resulted from intracellular accumulation (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these results suggest that the release or retention of the miRNAs that constitute the signature of acute HCV infection are selective and specific.

FIG 4.

Infection in vitro recapitulates the observed signature of circulating miRNAs in acute HCV infection in vivo. (A) Huh 7.5.1 hepatoma cells were infected with the J6/JFH-1 infectious clone of HCV (HCVcc) and compared to uninfected cells (mock). All cell cultures and virus were prepared using serum-free medium to avoid confounding measurement of highly conserved miRNAs in fetal bovine serum. After 24 h, cells were washed and the media replaced. Five days following infection, the ratio of the fold change of miRNAs in supernatants to fold change within cells (B) shows the relative enrichment or depletion of miRNAs in supernatants relative to cells. Cellular (C) and supernatant (D) abundance of miRNAs were normalized to intracellular snRNA U6 abundance. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from four replicate infections, and asterisks indicate significant (P < 0.05) changes from results for mock-infected controls.

Extracellular miRNAs and plasma HCV RNA abundance.

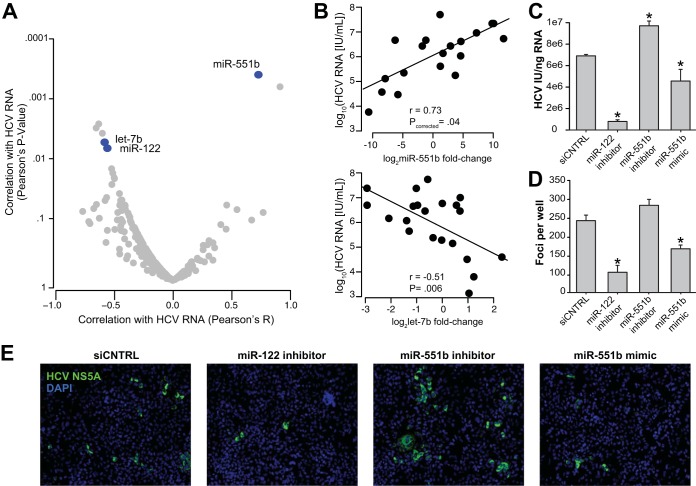

High HCV RNA levels during early acute infection have been found to be associated with spontaneous clearance (42). To understand potential determinants of HCV viremia in acute HCV infection, we examined changes in abundance of circulating miRNAs that were closely associated with HCV RNA levels at initial viremia (Fig. 5A), adjusting for multiple comparisons. The change in abundance of extracellular miR-551b was the most strongly associated with contemporaneous plasma HCV RNA levels (r = 0.73, Pcorrected = 0.04) (Fig. 5B), although the median (IQR) amplification score for miR-551b was 0.968 (0.899 to 1.024). As we found earlier, HCV RNA levels were inversely associated with plasma levels of miR-122 (Fig. 2C). In addition, we found an inverse association between HCV RNA levels and let-7b (r = −0.59, P = 0.005), an miRNA that is induced by type 1 and 3 interferons and has antiviral properties in vitro (43, 44).

FIG 5.

Circulating miR-122, let-7b, and miR-551b are associated with plasma HCV RNA abundance in acute infection. (A) Pearson's correlation P values are plotted for fold changes for each miRNA over preinfection and HCV RNA abundance at acute viremia. Blue points indicate miRNAs with significant relationships with HCV RNA either after correction for multiple comparisons (miR-551b) or at P < 0.05 for miRNAs with known impacts on HCV replication (miR-122 and let-7b). (B) Scatterplots indicate the association between plasma HCV RNA levels and the relative abundance of let-7b (upper) and miR-551b (lower). The regression line and corresponding Pearson's correlation coefficient is included. (C) Intracellular HCV RNA normalized to cellular RNA input from HCVcc-infected Huh 7.5.1 cells transfected with the indicated miRNA inhibitors or mimics. Error bars indicate standard deviations between four repeat transfections, and asterisks indicate significant changes in HCV RNA compared to the negative-control siRNA (siCNTRL). (D) Foci of infection, immunostained for HCV NS5A, were quantified from HCVcc-infected Huh 7.5.1 cells under the labeled conditions. (E) Representative images from source wells used for panel D showing NS5A in green and nuclei (DAPI) in blue.

To establish if miR-551b directly impacts HCV replication in hepatocytes, we transfected Huh 7.5.1 hepatoma cells with an miR-551b inhibitor and mature miR-551b mimic separately. miR-551b inhibition resulted in a significant increase in HCV RNA (P < 0.05), while the miR-551b mimic led to a decline in HCV RNA abundance (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5C). In comparison, miR-122 inhibition led to more potent suppression of HCV RNA levels. Transfection efficiency in these experiments was 81.5% ± 1.3% and was measured using FITC-conjugated scrambled oligonucleotide.

We confirmed the HCV RNA findings by quantifying HCV protein expression. Cells were transfected with an miR-551b mimic, inhibitor, and a scrambled siRNA; infected with HCV; and finally immunostained for the HCV NS5A protein. Cells that were treated with the miR-551b mimic showed a decrease in the number of infected cells compared to the scrambled siRNA control, while miR-551b antagonism led to an increase in the number of infected cells (Fig. 5D and E). Focus counting revealed a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in the number of foci in cells transfected with the miR-551b mimic; however, the increase in the number of foci observed in cells transfected with the miR-551b inhibitor did not reach significance (P = 0.1) (Fig. 5D).

DISCUSSION

By comparing plasma miRNA levels in a well-characterized cohort before, during, and after acute HCV infection, we identified a consistent and specific extracellular miRNA signature of acute infection that was confirmed in a separate cohort and in vitro. Contrary to conventional wisdom, circulating miRNA abundance during acute infection did not simply represent cellular necrosis but a nonrandom process of retention and release that correlates with the onset and control of virus infection.

miR-122 is the most abundant miRNA in the liver; its increase in plasma levels during chronic infection has been presumed to be analogous to elevated serum aminotransferase levels that are a consequence of cellular necrosis. However, miR-494, the second most abundant miRNA in the liver profiled, decreased in the plasma of acutely infected persons and was found to increase intracellularly upon infection. We also confirmed that there was no association of acute HCV infection with plasma abundance of miR-192, a liver-abundant microRNA that has been found to be increased in circulation during drug-induced liver injury (40, 41) and steatohepatitis (45). Taken together, these findings are inconsistent with necrolytic release of miRNAs and implicate selectivity in the release of cellular miRNAs that determines their plasma abundance.

Our miRNA isolation technique does not distinguish between free, exosome-associated, or virion-associated miRNAs. The observed increase in abundance of extracellular miR-122 upon HCV infection is consistent with the recent observations that miR-122 is packaged along with HCV RNA in exosomes (46). Moreover, the inverse relationship between circulating miR-122 and plasma HCV RNA levels suggests that miR-122 is not packaged directly into virions. Future research should focus on how miRNAs are differentially released and compartmentalized.

Circulating miRNA profiles have been associated with HCV infection in previous studies, although many of these studies were performed in persons with long-term chronic infection in whom liver fibrosis also may have contributed to miRNA abundance (47, 48). For example, changes in circulating miR-122 abundance have been reported in persons with chronic HCV infection and also in drug-induced liver injury (40) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (47). In addition, serum miR-122 levels in persons with chronic HCV infection who were treated with interferon and attained a sustained virologic response were higher than those in persons who had a null response (49, 50), and these results were explained largely by the genetic susceptibility marker near the IFNL3 gene. In contrast, we did not find an association between the change in miR-122 levels upon acute infection and the outcome of infection or IFNL3 genotype (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), although our sample size was not powered for this question. Given that there is an established positive association between HCV clearance and peak HCV RNA abundance (42) and that we found a negative relationship between circulating miR-122 and HCV RNA, it is logical to speculate that the association between circulating miR-122, IFNL3, and HCV clearance is consistent with what was observed during interferon treatment responses. However, we acknowledge that conclusive proof would require the study of a larger cohort. We also note that we did not find changes in the abundance of miR-20a and miR-92a, in contrast to a previous report of miRNAs during acute HCV infection (12), although their study populations were composed of participants with symptomatic jaundice, which occurs during no more than 20% of acute HCV infections.

Circulating miR-885-5p has been less extensively characterized than miR-122. Gui et al. reported that serum miR-885-5p levels are increased in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis, and chronic hepatitis B (51). Our finding that miR-885-5p was elevated in acute infection is consistent with these previous findings and suggests that elevation in plasma miR-885-5p is part of a conserved response to liver stress.

To date, only two other publications exist regarding the role of miR-551b in any biological process (52, 53). Fu et al. described a downregulation of miR-551b in hepatoma cells expressing a mutant of the hepatitis B virus HBx protein that induces higher levels of cellular proliferation, and Xu et al. described a role for miR-551b in acquired apoptosis and chemotherapy resistance in human lung cancer cell lines. Interestingly, we found that this miRNA reduced HCV replication even after adjusting for cellular abundance (Fig. 5). Further investigation into the mechanism of miR-551b is necessary and may reveal a novel antiviral response mediated by miR-551b with activity against viruses other than HCV.

Interestingly, both miR-122 (54–57) and miR-885-5p (58–60) have been identified as potent tumor suppressors with functional significance in cancer progression. In contrast, miR-494, which decreased in plasma abundance but increased within hepatocytes during acute HCV infection, has been reported to have oncogenic potential in hepatocytes (61) and antiproliferative effects in breast cancer cells (62). As mentioned above, miR551b appears to have proliferative and antiapoptotic properties in certain settings. Recent attention has focused on extracellular miRNAs as having the potential to regulate recipient cell gene expression (16–24); therefore, it is possible that the changes in extracellular miRNAs during acute HCV infection compose part of an innate response to viral infection that modulates cellular proliferation and viral replication. Our finding that HCV RNA levels were inversely associated with changes in extracellular let-7b, a known antiviral agent that is induced by interferon, supports the hypothesis that the circulating miRNA signature is part of an antiviral response.

There were several limitations to this study. The large number of miRNAs considered increases the risk of type 1 error, i.e., false discovery. Accordingly, we took a conservative approach by correcting for multiple comparisons. More importantly, we confirmed our findings using multiple approaches: (i) by identifying the same signature in a completely distinct group of individuals in the UFO cohort; (ii) by finding that miRNA levels of the signature were invariant in uninfected IDUs over matching time intervals; and (iii) by confirming the signature in vitro. We note that differences at baseline between the discovery and validation cohorts should have made it less likely that we would find the same circulating miRNA signature by chance, further supporting the validity of our findings.

On the other hand, it is possible that some small associations of miRNAs with acute HCV infection were missed by a study of this size. However, unlike larger cross-sectional studies in which disease associations often are confounded by person-to-person variability, we studied longitudinal samples in the same person before, during, and after acute HCV infection to establish consistent patterns of circulating miRNA abundance. Relative to cross-sectional studies, this approach markedly improved our power by controlling for person-to-person variance.

Another limitation is that we did not sample liver directly. However, it would be unethical to use liver tissue in humans obtained for that purpose, since liver biopsy specimens are not routinely indicated during acute HCV infection and are very rarely performed before HCV infection. Therefore, we examined miRNA changes in hepatoma cells infected with HCV in vitro and used previously published data on miRNA expression in healthy liver.

There are remaining questions about the role of circulating miRNAs in acute HCV infection. Our results suggest that extracellular miRNA release is sequence specific and correlates with the onset and outcome of HCV infection. Given the contribution of the implicated miRNAs in HCV replication and the prediction of clinical outcomes during chronic infection, these findings also suggest that the pathophysiology of chronic HCV infection can be established acutely as part of an innate response to viral infection. Future research is required to understand the mechanism of miRNA sorting and the role of plasma miRNAs in HCV infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants of the BBAASH and UFO studies for contributing these invaluable samples, William Osburn for expertise with regard to BBAASH sampling, and Roxann Ashworth for assistance with the qPCR array platform.

We also thank the National Institutes of Health for their financial support through grants R01 DA 016078, U19 AI 088791, R37 DA 013806, 5R01 DA 031056, and 2R01 DA 016017.

R.E.-D. provided study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis. L.N.W. performed acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. K.W.W. performed analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.R.B. provided analysis and interpretation of data. K.P. obtained funding and material support and provided study supervision. S.C.R. provided study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; and performed study supervision. A.L.C. provided study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; and performed study supervision. D.L.T. provided study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis; obtained funding; and performed study supervision. A.B. provided study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis and also obtained funding.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00955-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, Anania FA, Schaeffer M, Galai N, Nolt K, Nelson KE, Strathdee SA, Johnson L, Laeyendecker O, Boitnott J, Wilson LE, Vlahov D. 2000. The natural history of hepatitis c virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA 284:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox AL, Netski DM, Mosbruger T, Sherman SG, Strathdee S, Ompad D, Vlahov D, Chien D, Shyamala V, Ray SC, Thomas DL. 2005. Prospective evaluation of community-acquired acute-phase hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 40:951–958. doi: 10.1086/428578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maheshwari A, Ray S, Thuluvath PJ. 2008. Acute hepatitis C. Lancet 372:321–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kong YW, Ferland-McCollough D, Jackson TJ, Bushell M. 2012. microRNAs in cancer management. Lancet Oncol 13:e249–e258. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köberle V, Kronenberger B, Pleli T, Trojan J, Imelmann E, Peveling-Oberhag J, Welker M-W, Elhendawy M, Zeuzem S, Piiper A, Waidmann O. 2013. Serum microRNA-1 and microRNA-122 are prognostic markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 49:3442–3449. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bala S, Petrasek J, Mundkur S, Catalano D, Levin I, Ward J, Alao H, Kodys K, Szabo G. 2012. Circulating microRNAs in exosomes indicate hepatocyte injury and inflammation in alcoholic, drug-induced, and inflammatory liver diseases. Hepatology 56:1946–1957. doi: 10.1002/hep.25873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menéndez P, Padilla D, Villarejo P, Palomino T, Nieto P, Menéndez JM, Rodríguez-Montes JA. 2013. Prognostic implications of serum microRNA-21 in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 108:369–373. doi: 10.1002/jso.23415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Tan N, Yang J, Liu X, Cao X, He P, Dong X, Qin S, Zhang C. 2010. A translational study of circulating cell-free microRNA-1 in acute myocardial infarction. Clin Sci 119:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witwer KW. 2015. Circulating microRNA biomarker studies: pitfalls and potential solutions. Clin Chem 61:56–63. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.221341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leidner RS, Li L, Thompson CL. 2013. Dampening enthusiasm for circulating microRNA in breast cancer. PLoS One 8:e57841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellare P, Ganem D. 2009. Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 6:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrivastava S, Petrone J, Steele R, Lauer GM, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB. 2013. Up-regulation of circulating miR-20a is correlated with hepatitis C virus-mediated liver disease progression. Hepatology 58:863–871. doi: 10.1002/hep.26296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. 2005. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science 309:1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen HLA, Reesink HW, Lawitz EJ, Zeuzem S, Rodriguez-Torres M, Patel K, van der Meer AJ, Patick AK, Chen A, Zhou Y, Persson R, King BD, Kauppinen S, Levin AA, Hodges MR. 2013. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N Engl J Med 368:1685–1694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Liu K, Liu Y, Xu Y, Zhang F, Yang H, Liu J, Pan T, Chen J, Wu M, Zhou X, Yuan Z. 2013. Exosomes mediate the cell-to-cell transmission of IFN-α-induced antiviral activity. Nat Immunol 14:793–803. doi: 10.1038/ni.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Maiso P, Azab AK, Tai Y-T, Reagan M, Azab F, Flores LM, Campigotto F, Weller E, Anderson KC, Scadden DT, Ghobrial IM. 2013. BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J Clin Investig 123:1542–1555. doi: 10.1172/JCI66517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tadokoro H, Umezu T, Ohyashiki K, Hirano T, Ohyashiki JH. 2013. Exosomes derived from hypoxic leukemia cells enhance tube formation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 288:34343–34351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morello M, Minciacchi VR, de Candia P, Yang J, Posadas E, Kim H, Griffiths D, Bhowmick N, Chung LW, Gandellini P, Freeman MR, Demichelis F, Di Vizio D. 2013. Large oncosomes mediate intercellular transfer of functional microRNA. Cell Cycle 12:3526–3536. doi: 10.4161/cc.26539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet J-F, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. 2013. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:12048–12053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304718110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Balkom BWM, de Jong OG, Smits M, Brummelman J, den Ouden K, de Bree PM, van Eijndhoven MAJ, Pegtel DM, Stoorvogel W, Würdinger T, Verhaar MC. 2013. Endothelial cells require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood 121:3997–4006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-478925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xin H, Li Y, Buller B, Katakowski M, Zhang Y, Wang X, Shang X, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. 2012. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to neural cells contributes to neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells 30:1556–1564. doi: 10.1002/stem.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan MLG, Karlsson JM, Baty CJ, Gibson GA, Erdos G, Wang Z, Milosevic J, Tkacheva OA, Divito SJ, Jordan R, Lyons-Weiler J, Watkins SC, Morelli AE. 2012. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 119:756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. 2007. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittelbrunn M, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, González S, Sánchez-Cabo F, González MÁ Bernad A, Sánchez-Madrid F. 2011. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Commun 2:282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okoye IS, Coomes SM, Pelly VS, Czieso S, Papayannopoulos V, Tolmachova T, Seabra MC, Wilson MS. 2014. MicroRNA-containing T-regulatory-cell-derived exosomes suppress pathogenic T helper 1 cells. Immunity 41:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, Shiboski S, Lum P, Delwart E, Tobler L, Andrews W, Avanesyan L, Cooper S, Busch MP. 2009. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis 200:1216–1226. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray SC, Arthur RR, Carella A, Bukh J, Thomas DL. 2000. Genetic epidemiology of hepatitis C virus throughout Egypt. J Infect Dis 182:698–707. doi: 10.1086/315786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAlexander MA, Phillips MJ, Witwer KW. 2013. Comparison of methods for miRNA extraction from plasma and quantitative recovery of RNA from cerebrospinal fluid. Front Genet 4:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witwer KW, Sarbanes SL, Liu J, Clements JE. 2011. A plasma microRNA signature of acute lentiviral infection: biomarkers of central nervous system disease. AIDS 25:2057–2067. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b95bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. 2015. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wölk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. 1990. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med 9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hajarizadeh B, Grady B, Page K, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Cox AL, Rice TM, Sacks-Davis R, Bruneau J, Morris M, Amin J, Schinkel J, Applegate T, Maher L, Hellard M, Lloyd AR, Prins M, Dore GJ, Grebely J, InC3 Study Group. 2015. Patterns of hepatitis C virus RNA levels during acute infection: the InC3 study. PLoS One 10:e0122232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hajarizadeh B, Grady B, Page K, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Cox AL, Rice TM, Sacks-Davis R, Bruneau J, Morris M, Amin J, Schinkel J, Applegate T, Maher L, Hellard M, Lloyd AR, Prins M, Geskus RB, Dore GJ, Grebely J, InC3 Study Group. 2015. Factors associated with hepatitis C virus RNA levels in early chronic infection: the InC(3) study. J Viral Hepat 22:708–717. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hajarizadeh B, Grady B, Page K, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Cox AL, Rice TM, Sacks-Davis R, Bruneau J, Morris M, Amin J, Schinkel J, Applegate T, Maher L, Hellard M, Lloyd AR, Prins M, Geskus RB, Dore GJ, Grebely J, InC(3) Study Group. 2014. Interferon lambda 3 genotype predicts hepatitis C virus RNA levels in early acute infection among people who inject drugs: the InC(3) study. J Clin Virol 61:430–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacks-Davis R, Grebely J, Dore GJ, Osburn W, Cox AL, Rice TM, Spelman T, Bruneau J, Prins M, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Shoukry NH, Schinkel J, Allen TM, Morris M, Hajarizadeh B, Maher L, Lloyd AR, Page K, Hellard M, InC3 Study Group. 15 April 2015. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and spontaneous clearance of reinfection–the InC3 Study. J Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzur G, Israel A, Levy A, Benjamin H, Meiri E, Shufaro Y, Meir K, Khvalevsky E, Spector Y, Rojansky N, Bentwich Z, Reubinoff BE, Galun E. 2009. Comprehensive gene and microRNA expression profiling reveals a role for microRNAs in human liver development. PLoS One 4:e7511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randall G, Panis M, Cooper JD, Tellinghuisen TL, Sukhodolets KE, Pfeffer S, Landthaler M, Landgraf P, Kan S, Lindenbach BD, Chien M, Weir DB, Russo JJ, Ju J, Brownstein MJ, Sheridan R, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T, Rice CM. 2007. Cellular cofactors affecting hepatitis C virus infection and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:12884–12889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704894104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starkey Lewis PJ, Dear J, Platt V, Simpson KJ, Craig DGN, Antoine DJ, French NS, Dhaun N, Webb DJ, Costello EM, Neoptolemos JP, Moggs J, Goldring CE, Park BK. 2011. Circulating microRNAs as potential markers of human drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 54:1767–1776. doi: 10.1002/hep.24538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward J, Kanchagar C, Veksler-Lublinsky I, Lee RC, McGill MR, Jaeschke H, Curry SC, Ambros VR. 2014. Circulating microRNA profiles in human patients with acetaminophen hepatotoxicity or ischemic hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:12169–12174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412608111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu L, Fisher BE, Thomas DL, Cox AL, Ray SC. 2012. Spontaneous clearance of primary acute hepatitis C virus infection correlated with high initial viral RNA level and rapid HVR1 evolution. Hepatology 55:1684–1691. doi: 10.1002/hep.25575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witwer KW, Sisk JM, Gama L, Clements JE. 2010. MicroRNA regulation of IFN-beta protein expression: rapid and sensitive modulation of the innate immune response. J Immunol 184:2369–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng J-C, Yeh Y-J, Tseng C-P, Hsu S-D, Chang Y-L, Sakamoto N, Huang H-D. 2012. Let-7b is a novel regulator of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Mol Life Sci 69:2621–2633. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tryndyak V, de Conti A, Kobets T, Kutanzi K, Koturbash I, Han T, Fuscoe JC, Latendresse JR, Melnyk S, Shymonyak S, Collins L, Ross SA, Rusyn I, Beland FA, Pogribny IP. 2012. Interstrain differences in the severity of liver injury induced by a choline- and folate-deficient diet in mice are associated with dysregulation of genes involved in lipid metabolism. FASEB J 26:4592–4602. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-209569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bukong TN, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, Bala S, Szabo G. 2014. Exosomes from hepatitis C infected patients transmit HCV infection and contain replication competent viral RNA in complex with Ago2-miR122-HSP90. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004424. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cermelli S, Ruggieri A, Marrero JA, Ioannou GN, Beretta L. 2011. Circulating microRNAs in patients with chronic hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One 6:e23937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trebicka J, Anadol E, Elfimova N, Strack I, Roggendorf M, Viazov S, Wedemeyer I, Drebber U, Rockstroh J, Sauerbruch T, Dienes H-P, Odenthal M. 2013. Hepatic and serum levels of miR-122 after chronic HCV-induced fibrosis. J Hepatol 58:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su T-H, Liu C-H, Liu C-J, Chen C-L, Ting T-T, Tseng T-C, Chen P-J, Kao J-H, Chen D-S. 2013. Serum microRNA-122 level correlates with virologic responses to pegylated interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:7844–7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Estrabaud E, Lapalus M, Broët P, Appourchaux K, De Muynck S, Lada O, Martinot-Peignoux M, Bièche I, Valla D, Bedossa P, Marcellin P, Vidaud M, Asselah T. 2014. Reduction of microRNA 122 expression in IFNL3 CT/TT carriers and during progression of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Virol 88:6394–6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gui J, Tian Y, Wen X, Zhang W, Zhang P, Gao J, Run W, Tian L, Jia X, Gao Y. 2011. Serum microRNA characterization identifies miR-885-5p as a potential marker for detecting liver pathologies. Clin Sci 120:183–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu X, Tan D, Hou Z, Hu Z, Liu G, Ouyang Y, Liu F. 2012. Effect of microRNA on proliferation caused by mutant HBx in human hepatocytes. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 20:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu X, Wells A, Padilla MT, Kato K, Kim KC, Lin Y. 2014. A signaling pathway consisting of miR-551b, catalase and MUC1 contributes to acquired apoptosis resistance and chemoresistance. Carcinogenesis 35:2457–2466. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang B, Hsu S, Wang X, Kutay H, Bid HK, Yu J, Ganju RK, Jacob ST, Yuneva M, Ghoshal K. 2014. Reciprocal regulation of microRNA-122 and c-Myc in hepatocellular cancer: role of E2F1 and transcription factor dimerization partner 2. Hepatology 59:555–566. doi: 10.1002/hep.26712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bai S, Nasser MW, Wang B, Hsu S-H, Datta J, Kutay H, Yadav A, Nuovo G, Kumar P, Ghoshal K. 2009. MicroRNA-122 inhibits tumorigenic properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and sensitizes these cells to sorafenib. J Biol Chem 284:32015–32027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu S-H, Ghoshal K. 2013. MicroRNAs in liver health and disease. Curr Pathobiol Rep 1:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai W-C, Hsu S-D, Hsu C-S, Lai T-C, Chen S-J, Shen R, Huang Y, Chen H-C, Lee C-H, Tsai T-F, Hsu M-T, Wu J-C, Huang H-D, Shiao M-S, Hsiao M, Tsou A-P. 2012. MicroRNA-122 plays a critical role in liver homeostasis and hepatocarcinogenesis. J Clin Investig 122:2884–2897. doi: 10.1172/JCI63455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Afanasyeva EA, Mestdagh P, Kumps C, Vandesompele J, Ehemann V, Theissen J, Fischer M, Zapatka M, Brors B, Savelyeva L, Sagulenko V, Speleman F, Schwab M, Westermann F. 2011. MicroRNA miR-885-5p targets CDK2 and MCM5, activates p53 and inhibits proliferation and survival. Cell Death Differ 18:974–984. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan W, Zhang W, Sun L, Liu Y, You G, Wang Y, Kang C, You Y, Jiang T. 2011. Identification of MMP-9 specific microRNA expression profile as potential targets of anti-invasion therapy in glioblastoma multiforme. Brain Res 1411:108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan X, Liu Z, Liu H, Yu H, Wang L-E, Sturgis EM, Li G, Wei Q. 2013. A functional variant at the miR-885-5p binding site of CASP3 confers risk of both index and second primary malignancies in patients with head and neck cancer. FASEB J 27:1404–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim L, Balakrishnan A, Huskey N, Jones KD, Jodari M, Ng R, Song G, Riordan J, Anderton B, Cheung S-T, Willenbring H, Dupuy A, Chen X, Brown D, Chang AN, Goga A. 2014. MicroRNA-494 within an oncogenic microRNA megacluster regulates G1/S transition in liver tumorigenesis through suppression of mutated in colorectal cancer. Hepatology 59:202–215. doi: 10.1002/hep.26662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song L, Liu D, Wang B, He J, Zhang S, Dai Z, Ma X, Wang X. 2015. miR-494 suppresses the progression of breast cancer in vitro by targeting CXCR4 through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Oncol Rep 34:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.