ABSTRACT

HIV-1 Nef downregulates the viral entry receptor CD4 as well as the coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 from the surface of HIV-infected cells, and this leads to promotion of viral replication through superinfection resistance and other mechanisms. Nef sequence motifs that modulate these functions have been identified via in vitro mutagenesis with laboratory HIV-1 strains. However, it remains unclear whether the same motifs contribute to Nef activity in patient-derived sequences and whether these motifs may differ in Nef sequences isolated at different infection stages and/or from patients with different disease phenotypes. Here, nef clones from 45 elite controllers (EC), 46 chronic progressors (CP), and 43 acute progressors (AP) were examined for their CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 downregulation functions. Nef clones from EC exhibited statistically significantly impaired CD4 and CCR5 downregulation ability and modestly impaired CXCR4 downregulation activity compared to those from CP and AP. Nef's ability to downregulate CD4 and CCR5 correlated positively in all cohorts, suggesting that they are functionally linked in vivo. Moreover, impairments in Nef's receptor downregulation functions increased the susceptibility of Nef-expressing cells to HIV-1 infection. Mutagenesis studies on three functionally impaired EC Nef clones revealed that multiple residues, including those at novel sites, were involved in the alteration of Nef functions and steady-state protein levels. Specifically, polymorphisms at highly conserved tryptophan residues (e.g., Trp-57 and Trp-183) and immune escape-associated sites were responsible for reduced Nef functions in these clones. Our results suggest that the functional modulation of primary Nef sequences is mediated by complex polymorphism networks.

IMPORTANCE HIV-1 Nef, a key factor for viral pathogenesis, downregulates functionally important molecules from the surface of infected cells, including the viral entry receptor CD4 and coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4. This activity enhances viral replication by protecting infected cells from cytotoxicity associated with superinfection and may also serve as an immune evasion strategy. However, how these activities are maintained under selective pressure in vivo remains elusive. We addressed this question by analyzing functions of primary Nef clones isolated from patients at various infection stages and with different disease phenotypes, including elite controllers, who spontaneously control HIV-1 viremia to undetectable levels. The results indicated that downregulation of HIV-1 entry receptors, particularly CCR5, is impaired in Nef clones from elite controllers. These functional impairments were driven by rare Nef polymorphisms and adaptations associated with cellular immune responses, underscoring the complex molecular pathways responsible for maintaining and attenuating viral protein function in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

A number of viruses, including HIV-1 (1), other retroviruses (2), measles virus (3), influenza virus (4), and hepatitis B virus (5), have evolved ways to prevent superinfection of cells in which viral replication has been initiated. In HIV-1, the ∼27-kDa accessory protein Nef plays an important role in the downregulation of the viral entry receptor CD4 (6) and coreceptors CCR5 (1) and CXCR4 (7) on the surfaces of infected cells. Downregulation of entry receptors and coreceptors may protect infected cells from superinfection-associated cytotoxicity due to overaccumulation of integrated viral genomes (8, 9), thus enhancing viral replication (1, 7). Receptor downregulation may also reduce signaling that could otherwise induce apoptosis, modulate intracellular viral transcription, and affect cellular chemotaxis (10, 11). In addition, recent reports have indicated that Nef-mediated CD4 downmodulation helps to protect infected cells from antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, thereby promoting viral persistence (12, 13). The importance of Nef-mediated viral entry receptor downmodulation in HIV-1 pathogenesis is further demonstrated by natural variation in the ability of Nef clones isolated from infected individuals over the disease course to downregulate CD4 (14–17). Similarly, the impairment of these Nef activities in long-term nonprogressors (NP) (18), acute controllers (AC) (19), and elite controllers (EC) (20), who spontaneously suppress plasma viral loads (pVL) to undetectable levels in the absence of antiviral therapy, also supports their importance. However, it remains elusive whether Nef-mediated downregulation of CCR5 and CXCR4 also exhibits functional variation among primary clones and whether these functions are attenuated in HIV-1 controllers.

Despite being one of HIV-1's most variable proteins, Nef nevertheless possesses several functionally important, highly conserved motifs. Motifs responsible for each of Nef's functions have been identified in mutagenesis studies of laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strains (1, 6, 7, 21–25). For instance, CD4 and HLA class I downregulation activities are genetically separable. Loss of CD4 downregulation function can be achieved via disruption of the highly conserved motifs LL163,164 and DD174,175 (6, 22, 24), whereas alanine substitutions at M20, within the acidic cluster E62EEE65 and in the polyproline motif P72xxP78, affect HLA class I downregulation (21, 23, 25). The latter two motifs are additionally important for downregulation of both CCR5 and CXCR4 (1, 7).

In contrast, the locations and sequences of functionally important Nef motifs in naturally occurring (patient-derived) sequences remain poorly characterized. This is due in part to the extremely high sequence conservation of known motifs important for downregulation of CD4, HLA class I, and other receptors (14, 15, 17, 20, 26–30). Given that natural Nef sequences exhibit substantial functional heterogeneity (16, 17, 20, 31), it is reasonable to hypothesize that various secondary polymorphisms in Nef modulate these differences. Indeed, a recent report implicating a set of previously undescribed polymorphisms in modulating Nef-mediated HLA class I downregulation supports this hypothesis (26).

In the present study, we examined the downregulation of the HIV-1 entry receptor CD4 and coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 by Nef proteins derived from patients of diverse infection stages and phenotypes, including 45 EC, 46 CP, and 43 AP. We demonstrate that Nef clones from EC are significantly impaired in CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activity and modestly impaired in CXCR4 downregulation compared to those from CP and AP. In addition, by using EC Nef sequences with severely impaired function, we have identified various polymorphisms, including novel ones, that modulate Nef activity in natural sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

A total of 45 EC (median pVL of 2 RNA copies/ml, with an interquartile range [IQR] of 0.2 to 14 RNA copies/ml; median CD4 count of 811 [IQR, 612 to 1,022] cells/mm3) (20, 32) and 46 CP (median pVL, 80,500 [IQR, 25,121 to 221,250] RNA copies/ml; median CD4 count, 292.5 [IQR, 72.5 to 440] cells/mm3) (17) were studied as described previously. A total of 43 AP were identified during acute/early HIV-1 infection as defined by the Acute Infection Early Disease Research Program (AIEDRP) criteria (33) from cohorts in Boston, New York, and Berlin, Germany, as described previously (19, 34, 35). For each AP, the earliest available plasma sample was studied; these were collected a median of 54 [IQR, 36 to 72] estimated days postinfection. The median pVL among AP was 380,000 (IQR, 33,300 to 750,100) RNA copies/ml. All EC, CP, and AP were untreated at the time of sample collection and infected with HIV-1 subtype B. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Cloning and plasmid construction.

Control and patient-derived nef genes were amplified from plasma HIV-1 RNA by nested reverse transcription-PCR as described earlier (36) and cloned into the pIRES2-EGFP vector (Clontech), which coexpresses Nef and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), the latter via an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). A median of 3 nef clones was sequenced per patient, and a single clone with an intact Nef reading frame closely resembling the original bulk sequence was selected for analysis (17, 19, 20).

Nef-GFP fusion constructs were also generated for control and patient-derived Nef sequences. To do this, DNA fragments encoding Nef from the HIV-1 reference strain SF2, fused to GFP, were cloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) as described previously (37). Chimeric domain constructs between Nefs from primary isolates and SF2 cells were generated by overlap extension PCR. Defined mutations of interest were introduced into Nef-GFP fusion constructs by site-directed mutagenesis. All control, patient, and site-directed mutant Nef clones were reconfirmed by DNA sequencing of the entire nef region.

Naturally occurring Nef sequences exhibit length polymorphisms. To facilitate a consistent codon numbering scheme (based on the NefHXB2 reference strain), all clonal Nef sequences were aligned pairwise to NefHXB2 by using an in-house algorithm based on the HyPhy platform (38), and insertions were stripped out.

Western blot analysis.

TZM-bl cells (39) were transfected for 48 h with plasmid DNAs carrying genes for GFP alone or Nef-GFP fusion proteins, after which the cells were lysed in a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS (20, 27). The lysates (10 μg of protein each) were then subjected to SDS-PAGE in triplicate and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were separately probed using anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (Medical & Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan), anti-Nef polyclonal antisera (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), and anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (MAb; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

Nef clones of interest were transferred into a pNL4.3ΔNef plasmid as described previously (20, 30) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Recombinant viruses harboring nef from HIV-1 strain SF2 (NL43-NefSF2) or lacking nef (NL43-ΔNef) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. HEK-293T cells were transfected with each proviral clone, and viruses were harvested from the supernatant 48 h later. Cell lysates (10 μg protein each) were prepared, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described above. The blots were separately probed using anti-HIV-1 Gag p24 polyclonal antibody (BioAcademia, Osaka, Japan) and the same anti-Nef polyclonal antisera and anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody described above. In both cases, band intensities were quantified by using ImageQuant LAS 600 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Receptor downregulation analysis.

TZM-bl cells (39) were transfected for 48 h with plasmid DNAs harboring genes for GFP alone, Nef-IRES-GFP, or Nef-GFP fusion proteins. The resultant cells were stained with allophycocyanin-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CCR5 MAb (BD Pharmingen), brilliant violet-conjugated anti-human CD4 MAb (Biolegend), allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human CXCR4 MAb (Biolegend), and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD).

Cells of the human T cell line CEM, as well as primary CD4+ T lymphocytes, were electroporated with plasmid DNAs encoding GFP alone or Nef-GFP fusion proteins as previously described (16). Primary CD4+ T lymphocytes were prepared from PBMC of two HIV-negative donors followed by activation with phytohemagglutinin for 5 days and then separation of the CD4+ subset by magnetic cell sorting (Milteyni Biotech). For the CCR5 downregulation assay, the plasmid encoding human ccr5 (kindly provided by Kei Sato, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) was electroporated together with the plasmid DNAs encoding GFP alone or Nef-GFP fusion proteins. The resultant cells were stained with either anti-human CCR5 MAb or anti-human CD4 MAb and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD).

In both cases, the live cells (negative for 7-aminoactinomycin D) were gated, and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD4, CCR5, or CXCR4 in GFP+ (Nef-expressing) and GFP− subsets was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II or FACSVerse; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Results were expressed as the means of triplicate experiments, normalized to control plasmid expressing NefSF2, such that values of >100% and <100% indicated increased or decreased activity, respectively.

Superinfection protection assay.

The CCR5-tropic molecular clone pJRFL (kindly provided by Yoshio Koyanagi, Kyoto University, Japan) was digested with DraIII and XhoI, and the fragment encompassing the envelope region was subcloned into similarly digested pNL43 (40), giving rise to pNL43-ENVJRFL. Also, a part of the envelope region of pNL43 (between two BglII sites) was removed by digestion with BglII followed by religation of the resultant fragment (41), giving rise to pNL43-ΔENV. HEK-293T cells were transfected with NL43 (harboring intact ENVNL43) or NL43-ENVJRFL or were cotransfected with NL43-ΔENV and DNA encoding vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSVg). Virus-containing culture supernatants were collected 48 h later as previously described (28). TZM cells, seeded at 8 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate, were first transfected for 24 h with plasmid DNAs carrying genes for GFP alone or Nef-GFP fusion proteins containing various mutations of interest, collected, and reseeded at 8 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate. At 24 h after transfection, the resultant cells were then exposed to HIV-1 ENVNL43, HIV-1 ENVJRFL, or VSVg-pseudotyped virus for 48 h. In addition, cultures treated with the following inhibitors were used as additional controls: 1 μg/ml anti-CD4 MAb (clone SK3; Biolegend), 100 nM AMD3100 (CXCR4 inhibitor; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), or 100 nM Maraviroc (MVC; CCR5 inhibitor; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program). The resultant cells were collected, stained with 7-AAD followed by intracellular staining with phycoerythrin-labeled anti-p24 Gag MAb (KC-57; Beckman Coulter, CA), and analyzed by flow cytometry. The live (negative for 7-AAD) GFP+ subsets were gated and analyzed for the frequency of p24 Gag-expressing cells.

Statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise indicated, nonparametric statistics were employed throughout: the Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for differences between two groups, while correlations were analyzed using Spearman's test. In univariate analyses, a two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The Mann-Whitney U test was also used to identify amino acid residues in naturally occurring Nef sequences that were associated with function. In this analysis, multiple comparisons were addressed using q values, the P value analogues of the false-discovery rate (FDR), which denotes the expected proportion of false positives among results deemed significant at a given P value threshold (42). For example, at a q level of ≤0.2, we expect 20% of identified associations to represent false positives. For this analysis, statistical significance was defined as a P level of <0.05 and a q level of <0.2.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers assigned to the clonal nef sequences are JX171199 to JX171243 (EC) (20), JX440926 to JX440971 (CP) (17), and LC018135 to LC018177 (AP).

RESULTS

Downregulation of viral receptors CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 by patient-derived Nef clones.

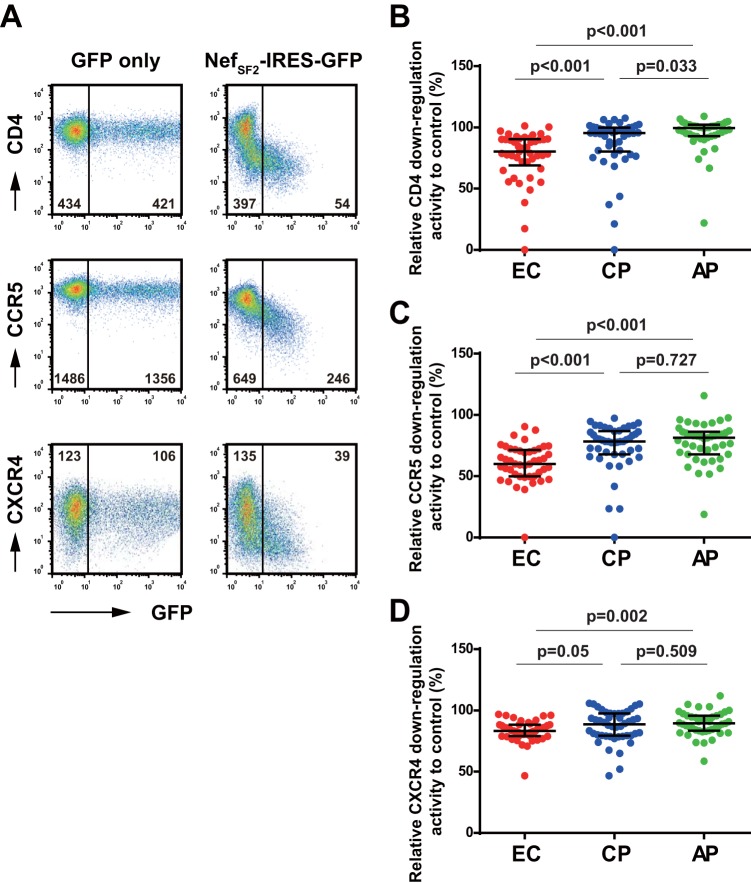

Transfection of TZM-bl cells with the NefSF2-IRES-GFP control strain resulted in a marked reduction in the cell surface expression of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 receptors (Fig. 1A presents a representative set of flow cytometry plots). Residual mean fluorescence intensities (calculated as the MFI of the GFP+ [Nef-expressing] subset divided by the GFP− subset) were 15.1% ± 2.8% (CD4), 42.7% ± 5.2% (CCR5), and 31.0 ± 6.5% (CXCR4) (means ± standard deviations [SD]), confirming previous observations (1, 6, 7, 28).

FIG 1.

Downregulation of viral receptors by Nef clones derived from EC, CP, and AP patients. (A) Plasmid DNAs harboring the laboratory-adapted NefSF2-IRES-GFP or GFP alone were transfected into TZM-bl cells, and the resultant cells were analyzed for cell surface expression of CD4 (top), CCR5 (middle), and CXCR4 (bottom). Representative flow cytometry plots measured on a FACSCanto II instrument are shown. The values given in the plots are the MFI of these viral receptors in the GFP− and GFP+ subsets. (B to D) Patient-derived Nef clones from 45 EC, 46 CP, and 43 AP were tested for their abilities to downregulate CD4 (B), CCR5 (C), and CXCR4 (D). Downregulation functions of patient-derived Nef sequences were normalized to that of control strain NefSF2 (whose function was set at 100%), such that normalized activities of >100% and <100% indicated increased and decreased activity relative to NefSF2, respectively. Each data point reflects the mean of triplicate determinations. Horizontal bars and whiskers indicate medians and interquartile ranges, respectively. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann-Whitney test.

We then analyzed 45 EC, 46 CP, and 43 AP Nef clones for their ability to downregulate these viral entry receptors. Receptor downregulation activities of the patient-derived Nef clones was normalized to activity of the control strain NefSF2, such that values of >100% or <100% indicated increased or decreased activity compared to NefSF2, respectively. EC Nef clones exhibited median CD4 downregulation activities of 80.2% (IQR, 68.9% to 90.3%) of that of NefSF2, values that were significantly lower than those of CP Nef clones (median, 95.3% [IQR, 80.2% to 99.8%]) and AP Nef clones (median, 99.4% [IQR, 92.9% to 102%]) (Fig. 1B). Importantly, the present data obtained for CD4 downregulation in TZM-bl cells by Nef clones from EC and CP were highly consistent with those previously derived from testing the same set of Nef clones in CEM T cells (17, 20) (Spearman's R = 0.9, P < 0.001).

Moreover, EC Nef clones exhibited median CCR5 downregulation activities of 60.0% (IQR, 49.8% to 71.3%) relative to control strain NefSF2, values that were significantly lower than those of CP Nef clones (median, 78.3% [IQR, 67.8% to 86.6%]) and AP Nef clones (median, 81.3% [IQR, 67.8% to 86.2%]) (Fig. 1C). In contrast, somewhat, EC Nef clones exhibited only modestly lower CXCR4 downregulation activity (median, 83.2% [IQR, 79.0% to 88.3%]) than CP Nef clones (median, 88.7% [IQR, 79.4% to 97.5%]) and AP Nef clones (median, 89.5% [IQR, 83.4% to 95.7%]), with only the latter comparison achieving statistical significance (Fig. 1D). CP and AP Nef clones differed only with respect to CD4 downregulation, with CP exhibiting modest yet significantly lower function than AP (Fig. 1B).

Relationship between ccr5 genotype and Nef's ability to downregulate CCR5.

Heterozygosity for the ccr5Δ32 mutation (ccr5+/−) is associated with durable control of HIV-1 infection (43, 44). We postulated that Nef-mediated CCR5 downregulation activity may be reduced in ccr5+/− subjects compared to ccr5+/+ subjects, as lower cell surface CCR5 expression in the former could reduce in vivo pressure on Nef to maintain robust CCR5 downregulation function. Seven out of 38 genotyped subjects were ccr5+/− in this EC cohort (32). However, no significant difference in Nef-mediated CCR5 downregulation between ccr5+/+ and ccr5+/− EC was observed (Mann-Whitney, P = 0.3).

Functional codependencies of Nef-mediated downregulation of viral receptors.

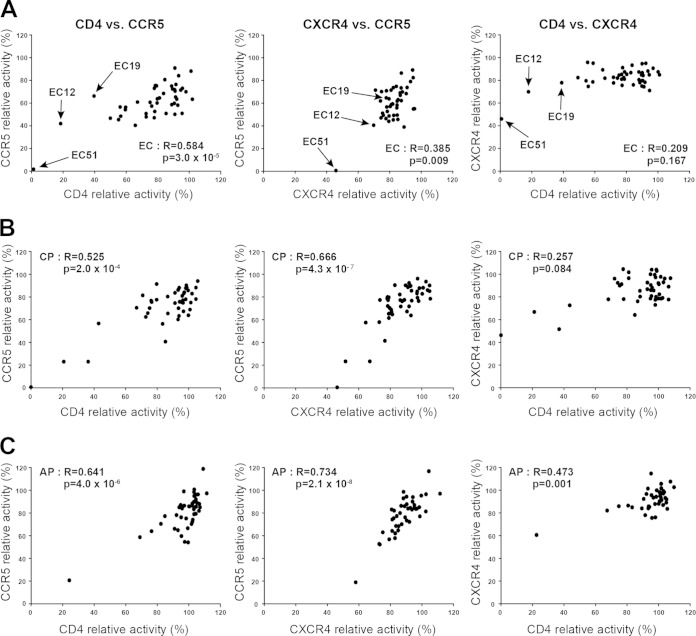

Mutational studies of laboratory-adapted Nef strains have identified the motifs LL163,164 and DD174,175 as being responsible for CD4 downregulation (6, 22, 24), whereas the acidic cluster E62EEE65 and the polyproline motif P72xxP78 are required for the downregulation of CCR5 and CXCR4 (1, 7). However, the extent to which secondary polymorphisms contribute to Nef-mediated viral receptor downregulation and the extent to which the various activities of patient-derived sequences are functionally independent remain incompletely known. Pairwise correlations of Nef-mediated viral receptor downregulation activities of EC Nef revealed significant positive relationships between CD4 and CCR5 downregulation capacities and between CXCR4 and CCR5 downregulation capacities (Fig. 2A). In addition, a weak positive relationship, though not statistically significant, was observed between CD4 and CXCR4 downregulation capacities (Fig. 2A). The same analyses were performed for Nef sequences from CP (Fig. 2B) and AP (Fig. 2C). Both CP and AP Nef sequences exhibited significant positive relationships between CD4 and CCR5 downregulation capacity and between CXCR4 and CCR5 downregulation capacity. In addition, Nef-mediated CD4 and CXCR4 downregulation capacities were significantly positively correlated in AP (Fig. 2C), and weakly positively correlated in CP (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Codependence of Nef-mediated HIV-1 receptor downregulation functions. Pairwise associations of relative downregulation activities of CD4 and CCR5, CCR5 and CXCR4, and CD4 and CXCR4 by Nef clones from EC (A), CP (B), and AP (C) cohorts are shown. Statistical analyses were performed using Spearman's correlation test. EC Nef clones EC12, EC19, and EC51 are indicated by arrows in panel A. Downregulation functions of patient-derived Nef sequences were normalized to NefSF2, and each data point reflects the mean of triplicate determinations.

Amino acids associated with Nef-mediated downregulation of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4.

To investigate the contribution of naturally occurring polymorphisms at Nef's variable sites on the function of patient-derived Nef sequences, we performed an exploratory sequence-function analysis restricted to amino acids observed at a minimum frequency of n = 5 in our data set. At the predefined P threshold of <0.05 and a q of <0.2, only one polymorphism (Arg-8) in EC Nef appeared to be associated with higher CCR5 downregulation function, although introduction of this mutation into NefSF2 resulted in no obvious functional difference (data not shown). No Nef codons were identified as significantly associated with CD4 or CXCR4 downregulation in EC. Among CP and AP, no Nef codons were identified as being significantly associated with any of the three Nef functions evaluated.

Distinct regions responsible for functional impairment in EC Nef clones.

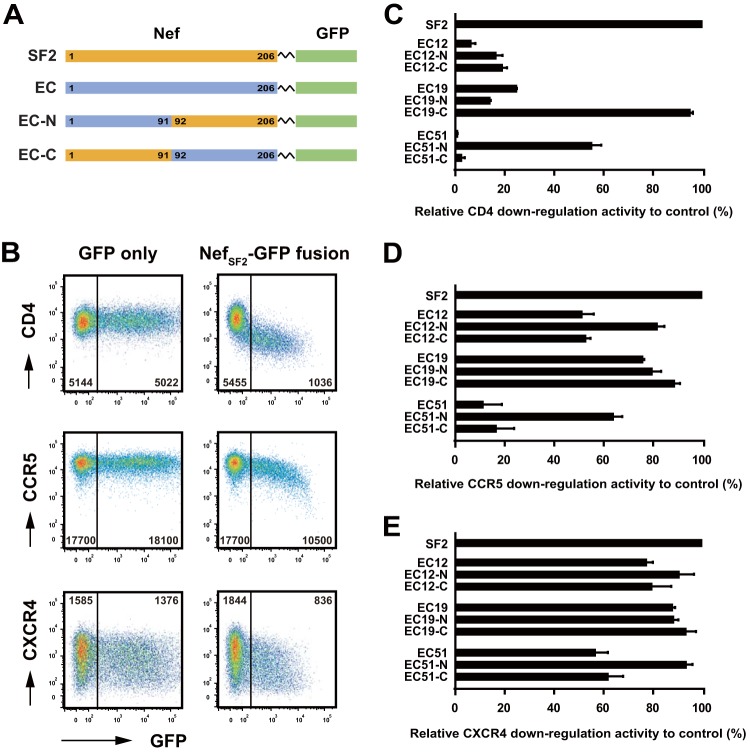

We next sought to identify naturally occurring polymorphisms responsible for impaired Nef-mediated viral receptor downregulation in individual Nef clones. We focused on three EC Nef clones, EC12, EC19, and EC51, that exhibited substantially diminished CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activities (Fig. 2A). These three patient-derived Nef clones encoded a large number of amino acid differences distributed throughout the Nef protein, so we first tried to broadly identify the Nef domain(s) responsible for reduced function. Chimeric constructs between EC clones and the SF2 control strain were constructed in the Nef-GFP fusion backbone (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the results obtained with the IRES system (Fig. 1A), the NefSF2-GFP fusion protein reduced cell surface CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 expression (Fig. 3B), exhibiting residual MFIs of receptor staining in the GFP+ (Nef-expressing) subset of 18.2% ± 1.5%, 54.7% ± 4.9%, and 49.7% ± 4.5%, respectively, relative to the GFP− subset.

FIG 3.

Mapping of Nef regions responsible for impaired downregulation functions. (A) Linear representations display the Nef-GFP fusion constructs used in this study. Nef codon numbering (1 to 206) was based on the HXB2 reference strain. Domains derived from NefSF2 (orange) and EC Nef clones (EC12, EC19, and EC51; blue) were combined at codons 91 to 92. (B) Plasmid DNAs carrying genes for NefSF2-GFP fusion protein or GFP alone were transfected into TZM-bl cells, and the resultant cells were analyzed for cell surface expression of CD4 (top), CCR5 (middle), and CXCR4 (bottom). Representative flow cytometry plots measured via a FACSVerse instrument are shown; the values given on the plots represent the MFIs of receptor staining in the GFP− and GFP+ subsets. Note that the absolute values of MFI here differed from those in Fig. 1A due to the sensitivity difference between flow cytometers. (C to E) The various Nef constructs were tested for their abilities to downregulate cell surface expression of CD4 (C), CCR5 (D), and CXCR4 (E). Downregulation function was normalized to NefSF2, which was arbitrarily set at 100%, and each data point reflects the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

For clone EC12, substituting the N- and C-terminal halves of EC12 with the corresponding part of NefSF2 (yielding chimeric constructs EC12-N and EC12-C, respectively) did not appreciably rescue CD4 downregulation function (Fig. 3C). This indicated that both the N- and C-terminal halves of Nef are responsible for the poor CD4 downregulation activity of this sequence. In contrast, CD4 downregulation activity in EC19 was rescued from 24.4 to 94.6% of the level of NefSF2 in chimera EC19-C (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the major determinants of poor CD4 downregulation function in this sequence map to its native N-terminal domain. Furthermore, in EC51, CD4 downregulation activity was rescued from 0.5 to 54.8% of the level of NefSF2 in chimera EC51-N (Fig. 3C), suggesting that important determinants of poor CD4 downregulation function in this sequence mapped to its native C-terminal domain. Taken together, results suggest that different Nef motifs are responsible for impaired CD4 downregulation activity in EC12, EC19 and EC51 Nef clones.

We also evaluated these chimeric constructs with respect to their CCR5 downregulation activity. In contrast, somewhat, to results for CD4 downregulation, EC12-N rescued CCR5 downregulation activity from 50.8 to 81.2% (Fig. 3D), indicating that different motifs modulate CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activities in this clone. EC19 was generally functional for CCR5 downregulation; nevertheless, exchanging the N terminus of this clone with the NefSF2 sequence (EC19-C) modestly improved CCR5 downregulation activity from 75.4 to 88.2% (Fig. 3D). Similar to results for CD4, CCR5 downregulation activity was rescued from 10.8 to 63.5% in EC51-N (Fig. 3D), suggesting that key determinants of poor CCR5 downregulation function in this sequence also map to its native C-terminal domain. Taken together, results suggest that different motifs were responsible for impaired downregulation of CCR5 in EC12, EC19, and EC51 Nef. Moreover, key determinants of CXCR4 downregulation function were similarly mapped for these clones (Fig. 3E). Whereas EC12 and EC19 were generally functional for CXCR4 downregulation, exchanging the C terminus of EC51 with the NefSF2 sequence (EC51-N) improved CXCR4 activity from 56.2 to 93.0%.

We also tested CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 downregulation activity of these constructs in the human CEM T cell line as well as primary CD4+ T cells. CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 downregulation activities in CEM cells for NefSF2 were all comparable with those obtained in TZM-bl cells (data not shown). In contrast, receptor downregulation activities of NefSF2 were relatively weak in primary CD4+ T cells: residual MFIs (of the GFP+ subset divided by the GFP− subset) were 32.0% ± 2.8% (CD4), 70.6% ± 2.7% (CCR5), and 80.3% ± 0.6% (CXCR4). Importantly however, the relative differences in CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 downregulation activities in all three EC Nef clones and their chimeric constructs measured in primary CD4+ T cells were consistent with those measured in TZM-bl cells and CEM cells (Pearson correlation, all R values > 0.9, P < 0.01), suggesting that the observed impairments in EC-derived Nef clones are independent of cell type.

Distinct regions responsible for steady-state protein expression levels in EC-Nef clones.

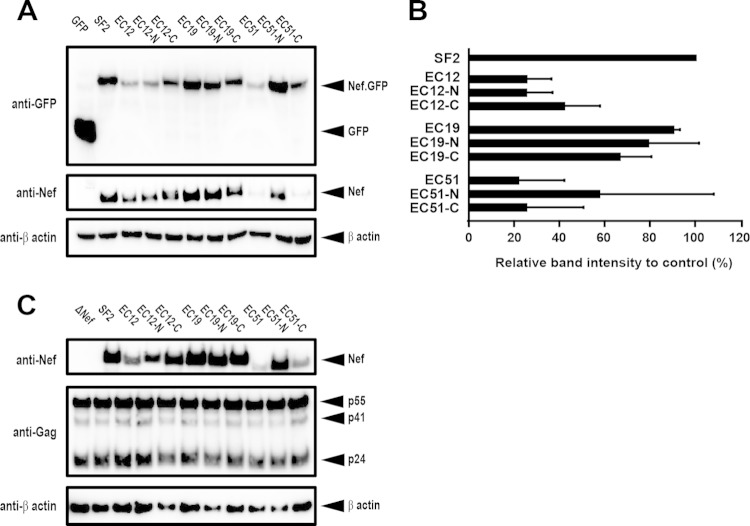

The steady-state expression level of Nef-GFP fusion proteins in TZM-bl cells was examined with an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 4A). EC12 Nef exhibited protein expression of 25.2% of the level of NefSF2, and EC12-C rescued it to 41.8%, whereas the protein expression level of EC12-N (25.1%) remained compromised (Fig. 4B). All EC19 and EC19 chimeras showed protein expression levels broadly comparable to NefSF2 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, EC51 Nef exhibited protein expression that was 21.6% of the NefSF2 level, and EC51-N rescued it to 57.3%, whereas the protein expression level of EC51-C (25.1%) remained compromised (Fig. 4B). We also analyzed the Nef-GFP protein expression level via staining with an anti-Nef antibody (Fig. 4A) and confirmed that both results were in good agreement.

FIG 4.

Western blot analysis of Nef chimeric constructs. (A) Western blot analysis of total cell lysates (10 μg of protein each) from TZM-bl cells transfected with DNA constructs encoding GFP alone or NefSF2-GFP, as well as EC-derived clones and GFP chimeras. The membranes with transferred proteins were stained with antibodies to GFP (top), Nef (middle), and β-actin (bottom). (B) Quantification of band intensities obtained from the anti-GFP staining. Steady-state expression was normalized to NefSF2, which was arbitrarily set at 100%, and each data point reflects the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. (C) Western blot analysis of total cell lysates (10 μg of protein each) from HEK-293T cells transfected with full-length proviral HIV-1 genomes expressing the various indicated Nef proteins. The membranes were stained with antibodies to Nef (top), Gag, and β-actin (bottom). Representative data (of two independent assays) are shown.

To characterize Nef expression in the context of a whole-virus construct, EC-derived Nef clones and their respective chimeras were cloned into NL43-based proviral plasmids, and the expression level of Nef and Gag proteins was analyzed in HEK-293T cells 48 h after transfection. Consistent with the Nef-GFP transfection experiments, a substantially reduced steady-state Nef expression level was observed for EC12 and EC12-N, as well as EC51 and EC51-C, though the expression levels of Gag protein and β-actin in the same samples was not much affected (Fig. 4C). In contrast, EC19 and their chimeric constructs showed expression levels of Nef and Gag comparable to the control, NL43-NefSF2 (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data indicate that different Nef motifs affected the steady-state protein expression levels among the EC Nef clones.

Fine-mapping sequence motifs responsible for impaired functions in individual EC-Nef clones.

Our initial chimeric experiments indicated that impairment of CD4, CCR5, and/or CXCR4 downregulation activities in different EC Nef clones was mediated by different Nef genetic regions. Specifically, CD4 downregulation and steady-state Nef protein levels in clone EC12 appeared to be modulated by components located throughout the Nef coding region (while CCR5 and CXCR4 downregulation in EC12 appeared to be modulated in part by motifs in its C-terminal domain). Due to the complexity of mapping such widespread sites, and the observation that CXCR4 downregulation activity of EC12 and its chimeras varied to a lesser extent than for other EC Nef clones (Fig. 3E), this clone was not followed further. In contrast, for clones EC19 and EC51, our initial chimeric experiments clearly implicated specific regions for follow-up. For EC19, determinants of both CD4 and CCR5 appeared to map to its native N terminus, whereas for EC51, key determinants of both function and steady-state protein levels appeared to map to its native C terminus. As such, these two clones were examined in fine-mapping experiments to identify specific Nef sequence determinants of CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activity in these clones.

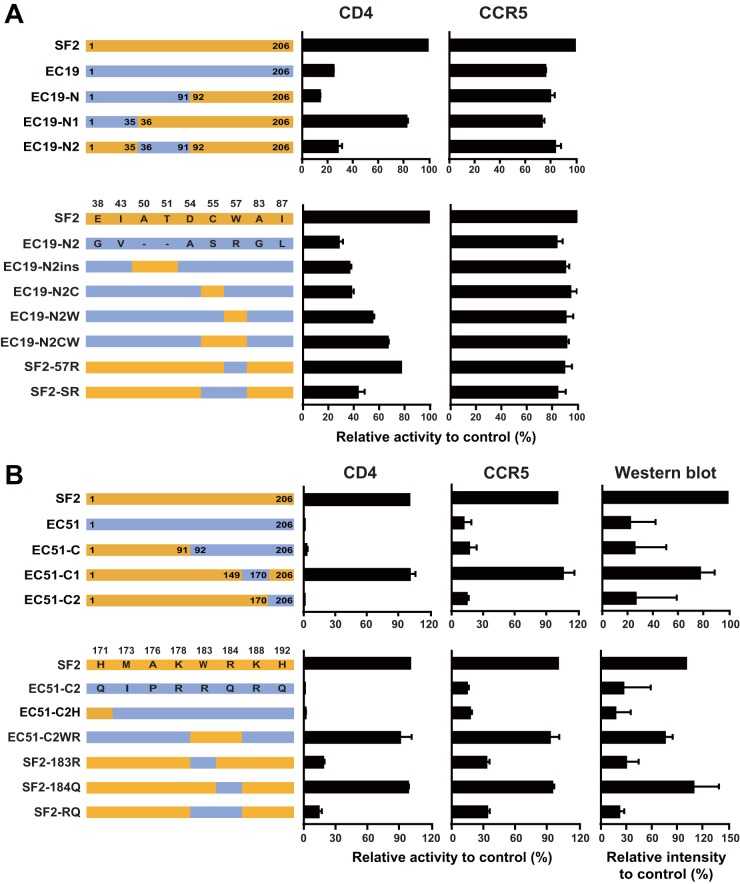

First, we further minimized the N-terminal part of EC19 on the NefSF2 backbone by constructing and functionally evaluating chimeras expressing EC19 Nef codons 1 to 35 (EC19-N1) and 36 to 91 (EC19-N2) in the NefSF2 backbone. In chimera EC19-N1, CD4 downregulation function was rescued to 82.0% of NefSF2 levels, while the function of EC19-N2 remained substantially compromised (27.7%). This result indicated that the major determinants of the CD4 downregulation defect of EC19 map to Nef positions 36 to 91, as function was largely rescued when this region was replaced by that of NefSF2 (Fig. 5A). In this region, EC19-Nef and NefSF2 differ at 9 residues: 38, 43, 50, 51, 54, 55, 57, 83, and 87 (Fig. 5A). It is notable that EC19 harbored exceedingly rare substitutions at some of these sites (e.g., 55C and 57R).

FIG 5.

Amino acid residues responsible for functional modulation of EC19 and EC51 Nef. (A) Various chimeric constructs between NefSF2 and EC19 Nef (top) and site-specific variants (bottom) were tested for their ability to downregulate cell surface expression of CD4 and CCR5. Amino acid residues that differed between NefSF2 and EC19 Nef in the 19-N2 region are shown. (B) Various chimeric constructs between NefSF2 and EC51 Nef (top) and site-specific variants (bottom) indicated in the figure were tested for their ability to downregulate cell surface expression of CD4 and CCR5. Amino acid residues that differed between NefSF2 and EC51 Nef in the 51-C2 region are shown. The activity was normalized to that of NefSF2, which was arbitrarily set at 100%, and each data point reflects the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

To further fine-map the residues responsible for the functional rescue, the following amino acid changes were introduced into EC19-N2: insertion of A and T residues at positions 50 and 51 (EC19-N2ins), introduction of an S-to-C substitution at codon 55 (EC19-N2C), and a substitution of the rare R with the highly conserved W at codon 57 (EC19-N2W) (Fig. 5A). These changes resulted in increases in CD4 downregulation activity from 27.7% (EC19-N2) to 36.1% (EC19-N2ins), 37.5% (EC19-N2C), and 54.2% (EC19-N2W) of that of NefSF2, respectively (Fig. 5A). Moreover, introductions of both the S-to-C and R-to-W substitutions at codons 55 and 57, respectively (EC19-N2CW) further increased CD4 downregulation activity to 66.4% of that of NefSF2, suggesting additive effects of these amino acid residues on modulation of CD4 downregulation activity. Conversely, changing Nef codon 57 from the highly conserved W to the rare R in NefSF2 (SF2-57R) decreased its CD4 downregulation activity to 76.9%, while changing both codons 55 and 57, respectively, by introducing C-to-S and W-to-R substitutions (SF2-SR) further decreased NefSF2's CD4 downregulation activity to 42.7% (Fig. 5A). In general, CCR5 downregulation activities of these mutant constructs were similarly affected by these changes, albeit to lesser extents (Fig. 5A).

Taken together, these results indicated that the presence of a rare residue at Nef codon 57 (57R), and to a lesser extent the presence of an uncommon residue at codon 55 (55S) and deletions at codons 50 and 51, contributed to the impaired CD4 downregulation activity of EC19's Nef sequence. Of interest, the 55S substitution has been identified as a noncanonical HLA-B*57-associated polymorphism in EC (20). Elite controller EC19 expressed HLA-B*57, suggesting that Nef-55S could have arisen via HLA-B*57-mediated immune escape in this individual.

We then moved on to EC51. For this clone, we further minimized its C-terminal part on the NefSF2 backbone by constructing and functionally evaluating chimeras expressing EC51 Nef codons 150 to 170 (EC51-C1) and EC51 Nef codons 171 to 206 (EC51-C2) on the NefSF2 backbone (Fig. 5B). In chimera EC51-C1, CD4 downregulation function was rescued to 100% of NefSF2 levels, while the function of EC51-C2 remained substantially compromised (0.4%) (Fig. 5B). This result indicated that the major determinants of the CD4 downregulation defect of EC51 map to Nef positions 171 to 206 (as function was 100% in all clones harboring the NefSF2 sequence in this region, but essentially 0% in all clones harboring EC51's sequence in this region). In this region, EC51-Nef and NefSF2 differ at 8 residues: 171, 173, 176, 178, 183, 184, 188, and 192 (Fig. 5B). Again, it is notable that EC51 harbored exceedingly rare substitutions at some of these sites (e.g., 171Q and 183R).

To further fine-map the residues responsible for the functional rescue, the following amino acid changes were introduced into EC51-C2: introduction of a Q-to-H substitution at 171 (EC51-C2H), and a double substitution from R to the highly conserved W at codon 183 and Q to R at codon 184 (EC51-C2WR). Whereas the function of EC51-C2H remained substantially compromised (1.1%), introduction of highly conserved 183W and 184R into EC51 (EC51-C2WR) resulted in its functional rescue to 90.5% of that of NefSF2 (Fig. 5B). Conversely, changing Nef codon 183 from the highly conserved W to R in NefSF2 (SF2-183R) decreased its CD4 downregulation activity to 17.7%, while changing Nef codon 184 from R to Q in NefSF2 (SF2-184Q) remained functional (98.1%) (Fig. 5B). Introducing both W183R and R184Q substitutions into NefSF2 decreased its CD4 downregulation activity to 13.5% (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results indicated that the presence of a rare residue at Nef codon 183 (183R) nearly fully explains the impaired CD4 downregulation function in EC51's Nef sequence.

CCR5 downregulation activities and steady-state protein expression levels of these mutant constructs were similarly affected by these changes (Fig. 5B). Moreover, in these constructs, significant positive associations were observed between CD4 downregulation function and protein expression level (Pearson R = 0.96, P = 0.0021) as well as CCR5 downregulation function and protein expression level (Pearson R = 0.94, P = 0.005). Taken together, these results indicate that the presence of a highly uncommon residue at Nef codon 183 (183R) not only contributed to the impaired CD4 downregulation function, but also impaired CCR5 downregulation activity in patient EC51's Nef sequence. Moreover, the Nef-183R-mediated functional impairment was also associated with the reduced steady-state protein expression level of this elite controller-derived Nef clone.

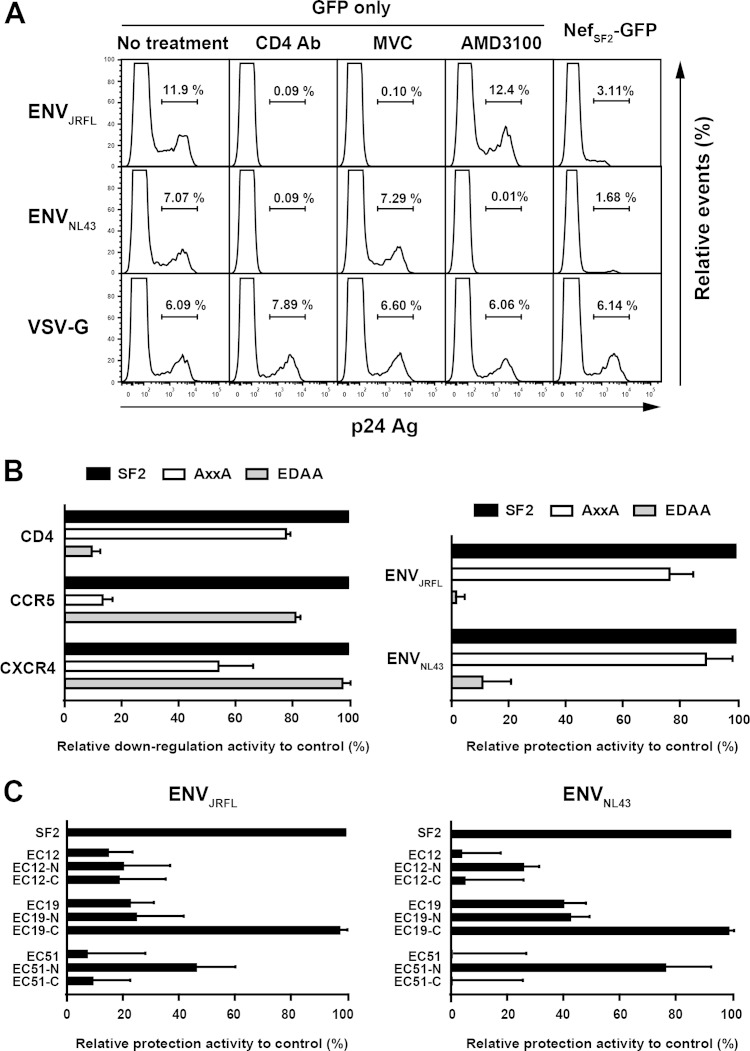

Effects of EC-Nef clones on susceptibility to HIV-1 superinfection.

We postulated that the differential ability to down-modulate viral entry receptors by patient-derived Nef clones would have consequences for the protection of HIV-infected cells from deleterious HIV-1 superinfection (1, 7, 28). Before testing this directly, we first undertook the following control experiments. We transfected GFP alone into TZM-bl cells and then exposed them to HIV-1 expressing various envelopes: ENVJRFL, a CCR5-using strain; NL43-ENVNL43, a CXCR4-using strain; and VSVg-pseudotyped HIV-1, which does not require CD4 or CCR5/CXCR4 coreceptors for entry. As expected, infection by HIV-ENVJRFL was nearly completely blocked by CD4 MAb or the CCR5 antagonist Maraviroc (MVC), while infection by HIV-ENVNL43 was nearly completely blocked by CD4 MAb or the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (Fig. 6A). Also as expected, infection by VSVg-pseudotyped virus was not blocked by any of these reagents (Fig. 6A). Next, TZM-bl cells were transfected with the NefSF2-GFP fusion protein and exposed to infection by these viruses. The NefSF2 expression in TZM-bl cells substantially protected the infection of HIV-ENVJRFL and HIV-ENVNL43 (Fig. 6A), with the frequency of infected cells (calculated as the frequency of the p24 Gag+ subset within GFP+ [Nef-expressing] cells) reduced to 22.0% ± 4.2% and 26.3% ± 2.8%, respectively, compared to TZM-bl cells expressing GFP only (no treatment). As expected however, NefSF2 expression in TZM-bl cells did not protect cells against infection by VSVg-pseudotyped HIV-1 (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Protection from HIV-1 superinfection. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots from the HIV-1 infection susceptibility assay. TZM cells transfected with GFP alone were subsequently exposed to HIV-ENVJRFL, HIV-ENVNL43, or VSVg-pseudotyped HIV-1 in the presence of anti-CD4 MAb, MVC, or AMD3100 (plus untreated control). Susceptibility of TZM cells transfected with NefSF2-GFP to various HIV-1 strains is also shown. The live (negative for 7-AAD) GFP+ subset was gated and then analyzed for intracellular expression of p24 Gag protein. The proportion of p24 Gag+ cells within the live GFP+ subset is indicated. (B) Receptor downregulation functions of NefSF2 and site-directed mutants AxxA and EDAA (left). Relative protection conferred by NefSF2, AxxA, and EDAA mutants from infection by HIV-ENVJRFL or HIV-ENVNL43 (right). (C) TZM-bl cells transfected with various EC-derived Nef clones and their chimeras were subsequently exposed to HIV-ENVJRFL (left) and ENVNL43 (right). Protection from HIV-1 infection was normalized to that with NefSF2, which was arbitrarily set at 100%, and each data point reflects the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

We then tested the following NefSF2 mutations known to specifically disrupt downregulation of CCR5/CXCR4 coreceptors and CD4, respectively: P72xxP78 to A72xxA78 (AxxA) and ED174,175 to AA174,175 (EDAA) (1, 7). As expected, the AxxA mutant exhibited substantial impairments in CCR5 and CXCR4 downregulation but no substantial change in CD4 downregulation function, whereas the EDAA mutations exhibited the opposite (Fig. 6B). We next examined the susceptibility of target cells expressing these Nef variants to infection by our panel of HIV-1 strains. The AxxA variant reduced the protection from infection by HIV-ENVJRFL and HIV-ENVNL43 only modestly (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the EDAA variant completely lost the protection from infection by both HIV-ENVJRFL and ENVNL43 (Fig. 6B). The results suggested that Nef-mediated CCR5 and CXCR4 downregulation modestly reduces the susceptibility of infected cells to HIV-1 infection, whereas Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation profoundly reduces their susceptibility to HIV-1 infection.

Next, we delivered the three EC-Nef clones (EC12, -19, and -51) and their chimeras into TZM-bl cells and tested these cultures for susceptibility to HIV-ENVJRFL infection. EC12 and its chimeras provided substantially decreased protection (<20%) against HIV-ENVJRFL infection compared to NefSF2 (Fig. 6C). EC19 and its chimera EC19-N also provided substantially decreased (<25%) protection against HIV-1 ENVJRFL infection. In contrast, EC19-C, which exhibited comparable CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activities to NefSF2 (Fig. 3C and D), also protected against HIV-ENVJRFL infection comparably to NefSF2 (Fig. 6C). As expected given their diminished CD4 and CCR5 downregulation functions (Fig. 3C and D), EC51 and EC51-C provided very poor protection against HIV-ENVJRFL infection (Fig. 6C). In contrast, EC51-N, which exhibited >50% of the CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activities of NefSF2 (Fig. 3C and D) provided 45.9% protection against HIV-ENVJRFL infection relative to NefSF2 (Fig. 6C). Overall, the extent of Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation function correlated positively with protection against HIV-ENVJRFL infection (Pearson R = 0.98, P = <0.001). However, preservation of Nef-mediated CCR5 downregulation function in some clones (e.g., EC12, EC12-N, EC12-C, EC19, and EC19-N, which exhibit >50% activity compared to NefSF2) (Fig. 3D) plays a part in retaining at least some protection against HIV-ENVJRFL infection.

We also evaluated the same set of Nef clones with respect to protection against HIV-ENVNL43 infection (Fig. 6C). Again, protection against HIV-ENVNL43 infection in Nef-expressing cells correlated positively with Nef's CD4 downregulation function (Pearson R = 0.93, P < 0.001). Furthermore, preservation of CXCR4 downregulation functions in patient-derived Nef clones (Fig. 3E) may play a role in retaining some protection against HIV-ENVNL43 infection (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the downregulation function of the viral entry receptor CD4 as well as the coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 differed markedly among Nef clones isolated from 45 EC compared to 46 CP and 43 AP. Specifically, the median CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activities of EC-derived Nef clones were significantly impaired compared to those of CP- and AP-derived Nef clones. Also, the median CXCR4 downregulation activity of EC-derived Nef clones was modestly impaired compared to that of CP- and AP-derived Nef clones, with the latter significantly so. In addition, these reductions in Nef's receptor downregulation functions increased the susceptibility of Nef-expressing cells to viral superinfection. By fine-mapping sequence determinants associated with decreased Nef-mediated CD4 and CCR5 downregulation activities in EC Nef clones, we revealed that combinations of amino acid variations unique to individual EC Nef clones (rather than particular Nef genetic determinants common to EC) were responsible, at least in part, for impairments in Nef function and steady-state protein expression levels in these patient sequences. Specifically, rare polymorphisms at highly conserved tryptophan residues (e.g., Trp-57 and Trp-183), deletions (e.g., AT50,51), and polymorphisms at HLA-associated sites (e.g., Cys-55) were responsible for reduced functions in the EC-derived Nef clones examined. These results indicated that unique sequence determinants, likely modulated by viral and host immune factors, contribute to the Nef functional attenuation observed in EC.

Certain cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape and HLA-associated polymorphisms in Nef have been shown to affect Nef functionality in chronic progressors (26, 27, 30), elite controllers (20), and patients at acute/early phases of infection who subsequently become controllers (19). Although previous studies investigated various Nef functions (including downregulation of CD4 and HLA class I, upregulation of CD74, enhancement of virion infectivity, and stimulation of viral replication), the effects of HLA-associated mutations on Nef's ability to downregulate chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 remain uncharacterized. As protective HLA class I alleles, most notably HLA-B*57, are overrepresented in EC (32, 44), it is possible that mutations associated with such alleles may impair Nef function in these individuals. Indeed, we previously identified noncanonical HLA-B*57-associated polymorphisms in the present EC cohort, including Nef substitutions 3G, 19R, E28D, C55X, V85L, I87L, Q105X, G178X, and M198X (20). To investigate the relationship between coreceptor downregulation and the presence of these HLA-B*57-associated polymorphisms among the 17 EC expressing this allele in our cohort, we assigned each of these Nef sequences a score reflecting the total number of HLA-B*57-associated polymorphisms contained therein. This number correlated negatively (albeit not significantly) with CCR5 (Spearman R = −0.45, P = 0.07) and CXCR4 (Spearman R = −0.39, P = 0.12) downregulation activities in these 17 HLA-B*57-expressing EC. These results suggest that Nef's ability to downregulate CCR5 and CXCR4 can be influenced at least to some extent by Nef polymorphisms selected under host cellular immune pressure.

Our study also illustrates that Nef motifs modulating function in natural Nef sequences may be different, and more complex, than those previously mapped in mutagenesis studies of reference strains. Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation has been reported to occur via two mechanisms: direct binding of Nef to the cytoplasmic tail of CD4 via Nef's WL57,58 motif (45), and Nef-mediated hijacking of the clathrin sorting pathway of CD4, mediated in part by Nef's LL163,164 motif (22, 46). In the former pathway, introduction of WL57,58-to-AA57,58 mutations into laboratory-adapted Nef strains substantially impaired CD4 downregulation activity (47). In contrast, in our study, introduction of the natural yet rare R57 polymorphism into NefSF2 conferred only a 20% reduction in CD4 downregulation activity; additional natural neighboring mutations (e.g., S55) were necessary to further impair Nef function. Moreover, among three EC Nef clones carrying R57 in our study (no CP or AP Nef clone carried this residue), only EC19 Nef exhibited <50% CD4 downregulation activity relative to NefSF2 (the other two exhibited >80% activity). These results suggest that, though individual polymorphisms can underlie functional impairments in some cases, in other cases their individual contributions are more subtle, and multiple naturally arising polymorphisms are required in combination to reduce Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation ability in EC. Measurement of direct binding of Nef to CD4 may help in understanding the differential downregulation function of Nef variants harboring mutations around W57. The LL163,164 motif of Nef was conserved in all Nef clones from all three cohorts; therefore, this motif is less likely to mediate functional heterogeneity of patient-derived Nef clones.

Mechanistic pathways of Nef-mediated downregulation of CCR5 and CXCR4 remain unclear. SIVmac239 Nef exhibits a more pronounced ability to downregulate CXCR4 than HIV-1 Nef (48). Moreover, this activity of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Nef is abolished by mutations that disrupt the clathrin adaptor protein 2 binding element located in the N-terminal region, which is unique to SIV Nef (48), suggesting the involvement of clathrin adaptor protein 2 in Nef-mediated CXCR4 downregulation. In HIV-1 Nef, introduction of alanine mutations in the acidic cluster E62EEE65 and the polyproline motif P72xxP78 disrupts both CCR5 and CXCR4 downregulation (1, 7). Nef's P72xxP78 motif overlaps those known to mediate HLA class I downregulation (21, 23, 25), which is mediated by clathrin adaptor protein 1 (49, 50). Furthermore, a recent report demonstrated that HIV-1 Nef downregulates C-C and C-X-C chemokine receptors, including CCR5 and CXCR4, via ubiquitin-dependent and -independent mechanisms (51). In our study, Nef-mediated viral entry receptor downregulation functions correlated positively in patient-derived sequences (Fig. 2), suggesting that these Nef functions are mechanistically linked to each other through common functional motifs or interactions with host proteins in vivo. Alternatively, various amino acid combinations within or outside known motifs may allow individual Nef clones to simultaneously adapt to each host's unique milieu in vivo. The observation that each EC-Nef clone harbored unique polymorphisms that contributed to its functional attenuation supports the latter hypothesis. Of note, we found no evidence of functional trade-offs or substitutions/domains that enhanced one function at the expense of another in any of the Nef clones examined here.

The HIV-1 Nef subtype B consensus sequence contains 7 tryptophan residues (at positions 5, 13, 57, 113, 124, 141, and 183); all of these are >95% conserved in the Los Alamos database. Conservation of Trp-183 is particularly high (1,466 out of 1,469 [99.8%] in the Los Alamos sequence database), suggesting its functional importance in vivo. Indeed, a recent report demonstrated that introduction of an unnatural W-to-A mutation at codon 183 alone impaired Nef's ability to enhance virion infectivity (52). However, the role of this residue in the function of natural Nef sequences, especially in terms of viral coreceptor downregulation, remains incompletely characterized. We demonstrated that introduction of the natural, albeit rare, W-to-R mutation at codon 183 in NefSF2 decreased its steady-state protein expression level by 70% and reduced downregulation activities of CD4 and CCR5 also by 70%. The downregulation of HLA class I was similarly disrupted by this mutation (data not shown). Therefore, the reduced Nef function is most likely attributable to this mutation's effect on steady-state protein expression levels, though further work is necessary to clarify the mechanism underlying this effect.

Viral genetic and functional studies of primary Nef clones face numerous challenges and limitations. Although Nef activities were assessed in HeLa-derived TZM-bl cells, CEM T cells, and primary CD4+ T cells with results in excellent agreement, Nef-mediated CD4, CCR5, and/or CXCR4 may nevertheless vary in other cell types and maturation stage of primary CD4+ T cells (51, 53–55). Also, although analysis of the intracellular localization of EC-derived Nef in various cell types may help to understand some of the observed functional impairments in EC-Nef, this aspect has not yet been tested. Furthermore, as the present and previous (18–20) studies reported relative impairments in EC Nef sequences for all Nef functions studied thus far, the relative contribution of various Nef functions to the EC phenotype still remains unclear. Similarly, the extents to which host and viral genetic factors contribute to functional impairments in EC-derived sequences remain unclear. Between CP and AP Nef clones, no essential differences were observed in CCR5 and CXCR4 downregulation functions, while modestly higher CD4 downregulation activity was seen in AP Nef clones (Fig. 1). Because this study examined cross-sectional cohorts, it remains unclear whether Nef-mediated CCR5 and CXCR4 downregulation activity is maintained throughout the course of infection. Rather, because Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation function correlates with viral replication in primary CD4+ T lymphocytes (18, 56), the modestly higher CD4 downregulation activity in AP Nef sequences observed in this study suggests that this activity is required during the early phase of infection.

In conclusion, our results suggest that Nef-mediated CD4, though not CCR5 or CXCR4, downregulation function differs across infection stages, with acute/early sequences exhibiting modestly higher function than those sampled at the chronic stage. More notably, Nef-mediated downregulation of primary (CD4) and secondary (CCR5 or CXCR4) viral entry receptors and resultant protection against HIV-1 superinfection were significantly impaired in Nef clones isolated from elite controllers. In the latter sequences, functional impairments were modulated by unique, host-specific combinations of rare polymorphisms (including some likely selected under in vivo cellular immune pressures), indicating that the functional modulation of primary Nef sequences is likely mediated by complex polymorphism networks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Philip Mwimanzi, Hirohito Ootsuka, Michiyo Tokunaga, and Hua Qian for their technical contributions to the initial stage of this study and Martin Markowitz for access to clinical specimens. We also acknowledge and thank the International HIV Controllers Study group, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Schwartz Foundation, and the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research.

This study was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan and by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (Research Program on HIV/AIDS) (to T.U.). M.M. is supported by the Otsuka Toshimi Scholarship Foundation. X.T.K. was supported by a Master's scholarship from the Canadian Association for HIV Research in partnership with Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada and ViiV Healthcare. M.A.B. holds a Canada Research Chair in Viral Pathogenesis and Immunity from the Canada Research Chairs Program. Z.L.B. is the recipient of a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Funders of this study played no role in determining the content of the manuscript or the decision to publish.

REFERENCES

- 1.Michel N, Allespach I, Venzke S, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. 2005. The Nef protein of human immunodeficiency virus establishes superinfection immunity by a dual strategy to downregulate cell-surface CCR5 and CD4. Curr Biol 15:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nethe M, Berkhout B, van der Kuyl A. 2005. Retroviral superinfection resistance. Retrovirology 2:52. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider-Schaulies J, Schnorr JJ, Brinckmann U, Dunster LM, Baczko K, Liebert UG, Schneider-Schaulies S, Ter Meulen V. 1995. Receptor usage and differential downregulation of CD46 by measles virus wild-type and vaccine strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:3943–3947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marschall M, Meier-Ewert H, Herrler G, Zimmer G, Maassab HF. 1997. The cell receptor level is reduced during persistent infection with influenza C virus. Arch Virol 142:1155–1164. doi: 10.1007/s007050050149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breiner KM, Urban S, Glass B, Schaller H. 2001. Envelope protein-mediated down-regulation of hepatitis B virus receptor in infected hepatocytes. J Virol 75:143–150. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.143-150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiken C, Konner J, Landau NR, Lenburg ME, Trono D. 1994. Nef induces CD4 endocytosis: requirement for a critical dileucine motif in the membrane-proximal CD4 cytoplasmic domain. Cell 76:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venzke S, Michel N, Allespach I, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. 2006. Expression of Nef downregulates CXCR4, the major coreceptor of human immunodeficiency virus, from the surfaces of target cells and thereby enhances resistance to superinfection. J Virol 80:11141–11152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01556-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauza CD, Galindo JE, Richman DD. 1990. Reinfection results in accumulation of unintegrated viral DNA in cytopathic and persistent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of CEM cells. J Exp Med 172:1035–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson HL, Zinkus DM. 1990. Accumulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA in T cells: results of multiple infection events. J Virol 64:4836–4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Yoder A. 2009. Chemokine coreceptor signaling in HIV-1 infection and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000520. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lama J. 2003. The physiological relevance of CD4 receptor down-modulation during HIV infection. Curr HIV Res 1:167–184. doi: 10.2174/1570162033485276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham T, Lukhele S, Hajjar F, Routy J-P, Cohen E. 2014. HIV Nef and Vpu protect HIV-infected CD4+ T cells from antibody-mediated cell lysis through down-modulation of CD4 and BST2. Retrovirology 11:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veillette M, Désormeaux A, Medjahed H, Gharsallah N-E, Coutu M, Baalwa J, Guan Y, Lewis G, Ferrari G, Hahn BH, Haynes BF, Robinson JE, Kaufmann DE, Bonsignori M, Sodroski J, Finzi A. 2014. Interaction with cellular CD4 exposes HIV-1 envelope epitopes targeted by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Virol 88:2633–2644. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03230-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson S, Shugars DC, Swanstrom R, Garcia JV. 1993. Nef from primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 suppresses surface CD4 expression in human and mouse T cells. J Virol 67:4923–4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchhoff F, Easterbrook P, Douglas N, Troop M, Greenough T, Weber J, Carl S, Sullivan J, Daniels R. 1999. Sequence variations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef are associated with different stages of disease. J Virol 73:5497–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann J, Byakwaga H, Kuang X, Le A, Brumme C, Mwimanzi P, Omarjee S, Martin E, Lee G, Baraki B, Danroth R, McCloskey R, Muzoora C, Bangsberg D, Hunt P, Goulder P, Walker B, Harrigan P, Martin J, Ndung'u T, Brockman M, Brumme Z. 2013. Ability of HIV-1 Nef to downregulate CD4 and HLA class I differs among viral subtypes. Retrovirology 10:100. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mwimanzi P, Markle TJ, Ogata Y, Martin E, Tokunaga M, Mahiti M, Kuang XT, Walker BD, Brockman MA, Brumme ZL, Ueno T. 2013. Dynamic range of Nef functions in chronic HIV-1 infection. Virology 439:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundquist CA, Tobiume M, Zhou J, Unutmaz D, Aiken C. 2002. Nef-mediated downregulation of CD4 enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in primary T lymphocytes. J Virol 76:4625–4633. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4625-4633.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuang XT, Li X, Anmole G, Mwimanzi P, Shahid A, Le AQ, Chong L, Qian H, Miura T, Markle T, Baraki B, Connick E, Daar ES, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Little S, Markowitz M, Pereyra F, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Ueno T, Brumme ZL, Brockman MA. 2014. Impaired Nef function is associated with early control of HIV-1 viremia. J Virol 88:10200–10213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01334-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mwimanzi P, Markle T, Martin E, Ogata Y, Kuang X, Tokunaga M, Mahiti M, Pereyra F, Miura T, Walker B, Brumme Z, Brockman M, Ueno T. 2013. Attenuation of multiple Nef functions in HIV-1 elite controllers. Retrovirology 10:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akari H, Arold S, Fukumori T, Okazaki T, Strebel K, Adachi A. 2000. Nef-induced major histocompatibility complex class I down-regulation is functionally dissociated from its virion incorporation, enhancement of viral infectivity, and CD4 down-regulation. J Virol 74:2907–2912. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.6.2907-2912.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg ME, Bronson S, Lock M, Neumann M, Pavlakis GN, Skowronski J. 1997. Co-localization of HIV-1 Nef with the AP-2 adaptor protein complex correlates with Nef-induced CD4 down-regulation. EMBO J 16:6964–6976. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piguet V, Wan L, Borel C, Mangasarian A, Demaurex N, Thomas G, Trono D. 2000. HIV-1 Nef protein binds to the cellular protein PACS-1 to downregulate class I major histocompatibility complexes. Nat Cell Biol 2:163–167. doi: 10.1038/35004038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren X, Park SY, Bonifacino JS, Hurley JH, Sundquist W. 2014. How HIV-1 Nef hijacks the AP-2 clathrin adaptor to downregulate CD4. eLife 3:e01754. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada T, Kaji N, Odawara T, Chiba J, Iwamoto A, Kitamura Y. 2003. Proline 78 is crucial for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef to down-regulate class I human leukocyte antigen. J Virol 77:1589–1594. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1589-1594.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis M, Lee P, Ng H, Yang O. 2012. Immune selection in vitro reveals human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef sequence motifs important for its immune evasion function in vivo. J Virol 86:7126–7135. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mwimanzi P, Hasan Z, Hassan R, Suzu S, Takiguchi M, Ueno T. 2011. Effects of naturally-arising HIV Nef mutations on cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition and Nef's functionality in primary macrophages. Retrovirology 8:50. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mwimanzi P, Hasan Z, Tokunaga M, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Ueno T. 2010. Naturally arising HIV-1 Nef variants conferring escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes influence viral entry co-receptor expression and susceptibility to superinfection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 403:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mwimanzi P, Markle TJ, Ueno T, Brockman MA. 2012. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I down-regulation by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 negative factor (HIV-1 Nef): what might we learn from natural sequence variants? Viruses (Basel) 4:1711–1730. doi: 10.3390/v4091711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ueno T, Motozono C, Dohki S, Mwimanzi P, Rauch S, Fackler O, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2008. CTL-mediated selective pressure influences dynamic evolution and pathogenic functions of HIV-1 Nef. J Immunol 180:1107–1116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahiti M, Brumme ZL, Jessen H, Brockman MA, Ueno T. 2015. Dynamic range of Nef-mediated evasion of HLA class II-restricted immune responses in early HIV-1 infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 463:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereyra F, Addo MM, Kaufmann DE, Liu Y, Miura T, Rathod A, Baker B, Trocha A, Rosenberg R, Mackey E, Ueda P, Lu Z, Cohen D, Wrin T, Petropoulos CJ, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD. 2008. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis 197:563–571. doi: 10.1086/526786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little SJ, Frost SD, Wong JK, Smith DM, Pond SL, Ignacio CC, Parkin NT, Petropoulos CJ, Richman DD. 2008. Persistence of transmitted drug resistance among subjects with primary human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol 82:5510–5518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02579-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Carlson J, Streeck H, John M, Eichbaum Q, Block BL, Baker B, Kadie C, Markowitz M, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Rosenberg E, Kaldor J, Yuki Y, Carrington M, Allen TM, Mallal S, Altfeld M, Heckerman D, Walker BD. 2008. Marked epitope- and allele-specific differences in rates of mutation in human immunodeficiency type 1 (HIV-1) Gag, Pol, and Nef cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes in acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Virol 82:9216–9227. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01041-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miura T, Brumme ZL, Brockman MA, Rosato P, Sela J, Brumme CJ, Pereyra F, Kaufmann DE, Trocha A, Block BL, Daar ES, Connick E, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Rosenberg E, Markowitz M, Schafer K, Vaida F, Iwamoto A, Little S, Walker BD. 2010. Impaired replication capacity of acute/early viruses in persons who become HIV controllers. J Virol 84:7581–7591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00286-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miura T, Brockman MA, Brumme CJ, Brumme ZL, Carlson JM, Pereyra F, Trocha A, Addo MM, Block BL, Rothchild AC, Baker BM, Flynn T, Schneidewind A, Li B, Wang YE, Heckerman D, Allen TM, Walker BD. 2008. Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite controllers: lack of gross genetic defects or common amino acid changes. J Virol 82:8422–8430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00535-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueno T, Idegami Y, Motozono C, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2007. Altering effects of antigenic variations in HIV-1 on antiviral effectiveness of HIV-specific CTLs. J Immunol 178:5513–5523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pond SLK, Frost SDW, Muse SV. 2005. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani RB, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Wu X, Shaw GM, Kappes JC. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1896–1905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yusa K, Song W, Bartelmann M, Harada S. 2002. Construction of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) library containing random combinations of amino acid substitutions in the HIV-1 protease due to resistance by protease inhibitors. J Virol 76:3031–3037. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.3031-3037.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeda Y, Terasawa H, Tanaka Y, Mitsuura C, Nakashima K, Yusa K, Harada S. 2015. Separate cellular localizations of human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) Env and glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) are required for HTLV-1 Env-mediated fusion and infection. J Virol 89:502–511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02686-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storey J, Tibshirani R. 2003. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley GA, Smith MW, Allikmets R, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder SP, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O'Brien SJ. 1996. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science 273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereyra F, Jia X, McLaren P, Telenti A, de Bakker P, Walker B, Ripke S, Brumme C, Pulit S, Carrington M. 2010. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 330:1551–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grzesiek S, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Bax A. 1996. The CD4 determinant for downregulation by HIV-1 Nef directly binds to Nef. Mapping of the Nef binding surface by NMR. Biochemistry 35:10256–10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaudhuri R, Lindwasser OW, Smith WJ, Hurley JH, Bonifacino JS. 2007. Downregulation of CD4 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is dependent on clathrin and involves direct interaction of Nef with the AP2 clathrin adaptor. J Virol 81:3877–3890. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02725-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mangasarian A, Piguet V, Wang J-K, Chen Y-L, Trono D. 1999. Nef-induced CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) down-regulation are governed by distinct determinants: N-terminal alpha helix and proline repeat of Nef selectively regulate MHC-I trafficking. J Virol 73:1964–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hrecka K, Swigut T, Schindler M, Kirchhoff F, Skowronski J. 2005. Nef proteins from diverse groups of primate lentiviruses downmodulate CXCR4 to inhibit migration to the chemokine stromal derived factor 1. J Virol 79:10650–10659. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10650-10659.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roeth JF, Collins KL. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef: adapting to intracellular trafficking pathways. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:548–563. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00042-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wonderlich ER, Williams M, Collins KL. 2008. The tyrosine binding pocket in the adaptor protein 1 (AP-1) mu1 subunit is necessary for Nef to recruit AP-1 to the major histocompatibility complex class I cytoplasmic tail. J Biol Chem 283:3011–3022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chandrasekaran P, Moore V, Buckley M, Spurrier J, Kehrl JH, Venkatesan S. 2014. HIV-1 Nef down-modulates C-C and C-X-C chemokine receptors via ubiquitin and ubiquitin-independent mechanism. PLoS One 9:e86998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jere A, Fujita M, Adachi A, Nomaguchi M. 2010. Role of HIV-1 Nef protein for virus replication in vitro. Microbes Infect 12:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laguette N, Brégnard C, Bouchet J, Benmerah A, Benichou S, Basmaciogullari S. 2009. Nef-induced CD4 endocytosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 host cells: role of p56lck kinase. J Virol 83:7117–7128. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01648-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelchen-Matthews A, Armes JE, Griffiths G, Marsh M. 1991. Differential endocytosis of CD4 in lymphocytic and nonlymphocytic cells. J Exp Med 173:575–587. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu H, Khalid M, Heigele A, Schmökel J, Usmani MS, van der Merwe J, Münch J, Silvestri G, Kirchhoff F. 2015. Lentiviral Nef proteins manipulate T cells in a subset-specific manner. J Virol 89:1986–2001. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03104-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glushakova S, Munch J, Carl S, Greenough TC, Sullivan JL, Margolis L, Kirchhoff F. 2001. CD4 down-modulation by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef correlates with the efficiency of viral replication and with CD4+ T-cell depletion in human lymphoid tissue ex vivo. J Virol 75:10113–10117. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10113-10117.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]