Abstract

To evaluate the efficacy of cardamom with pioglitazone on dexamethasone-induced hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia in albino rats. There were four groups of 6 rats each. First group received dexamethasone alone in a dose of 8 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 6 days to induce metabolic changes and considered as dexamethasone control. Second group received cardamom suspension 1 g/kg/10 mL of 2% gum acacia orally 6 days before dexamethasone and 6 days during dexamethasone administration. Third group received pioglitazone 45 mg/kg orally 6 days before dexamethasone and 6 days during dexamethasone administration. Fourth group did not receive any medication and was considered as normal control. Fasting blood sugar, lipid profile, blood sugar 2 h after glucose load, liver weight, liver volume were recorded, and histopathological analysis was done. The effects of cardamom were compared with that of pioglitazone. Dexamethasone caused hepatomegaly, dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia. Both pioglitazone and cardamom significantly reduced hepatomegaly, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia (P < 0.01). Reduction of blood sugar levels after glucose load was significant with pioglitazone in comparison to cardamom (P < 0.01). Cardamom has comparable efficacy to pioglitazone in preventing dexamethasone-induced hepatomegaly, dyslipidemia, and fasting hyperglycemia.

Keywords: Anti-diabetic, cardamom, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Over the past three decades, the number of people with diabetes mellitus has more than doubled globally, making it one of the most important public health challenges to all nations. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and pre-diabetes are increasingly observed among children, adolescents, and younger adults. The causes of the epidemic of T2DM are embedded in a very complex group of genetic and epigenetic systems interacting within an equally complex societal framework that determines the behavior and environmental influences. Prevention of T2DM is a “whole-of-life” task and requires an integrated approach operating from the origin of the disease.[1] Insulin resistance in muscle, liver, and fat is a prominent feature of most patients with T2DM and obesity, resulting in a reduced response of these tissues to insulin.[2]

Currently, a number of synthetic hypolipidemic drugs are available and are effective, but they are associated with severe side effects. Therefore, alternative approaches are eagerly needed, and plant-based therapies attract much interest, as they are effective in reducing lipid levels and show minimal or no side effects. Oral administration of cardamom extract significantly reduced total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein, and very low density lipoprotein and triglycerides in Wistar rats.[3]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of cardamom powder suspension

Dry cardamom seeds were procured from the market. They were made into a fine powder with the help of a pulverizer. This fine powder was taken in a mortar. 2% gum acacia was added little by little and triturated continuously to obtain the suspension.

Experimental animal

Healthy adult rats of Wistar strain weighing around 240–270 g were used in the present study. The animals were housed in clean polypropylene cages and maintained in a well-ventilated temperature controlled animal house with constant 12 h light/dark schedule. The animals were fed with standard rat pellet diet and clean drinking water was made available ad libitum. All animal procedures have been approved and a prior permission from the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC) was obtained as per prescribed guidelines with ethical clearance number KSHEMA/IAEC/04/2012.

Induction of hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia

Hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia were induced according to the procedure described by Shalam et al.[4]

Experimental methods

A total of 24 rats were divided into four groups with 6 rats in each group. Body weight was checked for all groups on day 1, day 7, and on day 12.

First group received dexamethasone alone in a dose of 8 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 6 days to induce metabolic changes and considered as dexamethasone control.

Second group received cardamom powder suspension in 2% gum acacia 1 g/kg/10 ml, oral, 6 days before, and 6 days during dexamethasone administration.

Third group received pioglitazone 45 mg/kg orally, 6 days before dexamethasone, and 6 days during dexamethasone administration.

Fourth group did not receive any medication and was considered as normal control.

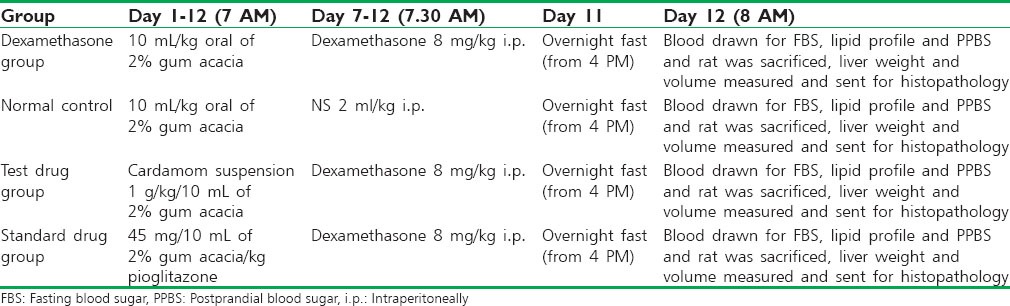

Rats were fasted overnight; blood was collected by retro-orbital sinus puncture for fasting blood sugar, lipid profile, and 2 h after a glucose load of 2 g/10 ml/kg IP (postprandial blood sugar). Rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Liver was dissected out, liver weight, liver volume were measured. Livers were stored in 10% formalin and sent for histopathological analysis. The details of the study method are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study protocol

Statistical analysis

Data management was done in excel after cleaning and coding. Then the data were transferred to SPSS package (SPSS Inc. Released 2008. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.) for analysis. The values presented as mean ± standard deviation. Independent t-test was used to compare between two groups. ANOVA with Scheffe's post-hoc test was done for multiple comparisons. A value of P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

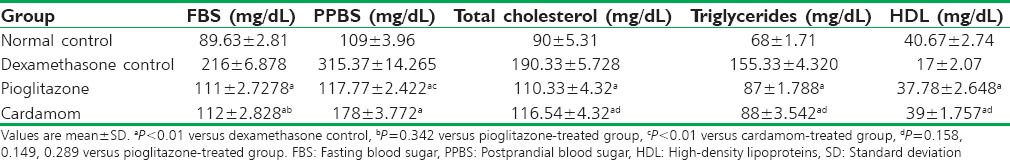

Effect of cardamom on blood sugar levels in rats

The blood sugar levels of four groups are presented in Table 2. An increase in blood sugar levels was seen in the dexamethasone group as compared to the normal group. A significant decrease in the fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels was observed in the cardamom and pioglitazone-treated groups as compared to dexamethasone control group (P < 0.01). The fasting blood glucose levels in the cardamom-treated group was comparable to pioglitazone group (P = 0.486). A corresponding significant decrease in postprandial blood glucose levels was observed (P < 0.01) in the pioglitazone group as compared with cardamom group.

Table 2.

Effect of cardamom on blood sugar levels and lipids in rats (n=6 per group)

Effect of cardamom on lipids

The lipid profiles of four groups are presented in Table 2. An increase in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and decrease in HDL was seen in the dexamethasone group as compared to the normal group. A significant decrease in the total cholesterol and triglyceride, and increase in HDL levels was observed in the cardamom and pioglitazone-treated groups as compared to dexamethasone control group (P < 0.01). The total cholesterol, triglyceride, and HDL levels in the cardamom-treated group was comparable to pioglitazone group (P = 0.098, 0.154, and 0.312).

Effect of cardamom on liver weight and liver volume

The liver weight and liver volume of four groups are presented in Table 3. An increase in the liver weight and liver volume was seen in the dexamethasone group as compared to the normal group. A significant decrease in the liver weight and liver volume was observed in the cardamom and pioglitazone-treated groups as compared to dexamethasone control group (P < 0.01). The liver weight and liver volume in the cardamom-treated group were comparable to pioglitazone group (P = 0.248, P = 0.095).

Table 3.

Effect of cardamom on liver weight, liver volume, and body weight in rats (n=6 per group)

Effect of cardamom on body weight

The body weights of four groups are presented in Table 3. There was a weight loss seen in the dexamethasone group as compared to on day 12. A significant increase in the body weight was observed in the cardamom- and pioglitazone-treated groups as compared to dexamethasone control group (P < 0.01). The body weight in the cardamom-treated group was comparable to pioglitazone group (P = 0.304).

Histopathological observations

As depicted in Figure 1, the Normal control group rats showed normal hepatocytes. The dexamethasone-treated group showed an increase in the size of hepatocytes, cytoplasm is vesicular to clear. Fat deposition was observed. The hepatocytes in rats treated with pioglitazone and cardamom were smaller in size and had reduced fat deposition compared to dexamethasone-treated group.

Figure 1.

Histopathological changes of rat liver tissue (H and E, ×40). (a) Hepatocytes in normal control group. (b) Hepatocytes in dexa-treated group showing fat deposition pushing the nucleus to the periphery. (c) Hepatocytes showing reduced fat deposition in pioglitazone-treated rats. (d) Hepatocytes showing reduced fat deposition in cardamom-treated rats

DISCUSSION

Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) in a dose of 3 g in 2 divided doses per day over 3 months reduced systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure, increased fibrinolytic activity, and enhanced antioxidant status in a study of newly diagnosed individuals with primary hypertension of stage 1.[5] In vitro studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of cardamom.[6] An in vitro study of aqueous extract of cardamom on human platelets showed a protective effect on platelet aggregation and lipid peroxidation.[7] Cardamom is used along with chickpea and barley as a traditional herbal medicine for the treatment of diabetes.[8] A US patent mentions the use of polyherbal preparations containing cardamom for use in diabetes.[9] These features made us to look for any beneficial effect on glucocorticoid-induced metabolic syndrome.

Glucocorticoids are used in a broad spectrum of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies, which include allergic and hematological disorders, and renal, intestinal, liver, eye, and skin diseases. Rheumatic diseases and bronchial asthma are the main indications of long-term therapy with these hormones. In addition, glucocorticoids are also used in the suppression of the host-versus-graft or graft-versus-host reactions following organ transplantation surgery.[10] Glucocorticoids, as endogenous hormones and prevalent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs, have been reported to induce Cushing's syndrome, which is characterized by central obesity and insulin resistance.[11] In addition, chronic treatment with synthetic glucocorticoids like dexamethasone has been associated with hyperinsulinemia in both animal and human research[12,13] elevation of 11β- hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (HSD1) and an increased generation of cortisol from cortisone in skeletal muscle[14] and adipose tissue[15] have also been identified in obese insulin-resistant humans, although plasma concentration of cortisol is not above the normal range. In transgenic mice, hepatic 11β-HSD1 overexpression shows a modest insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, but no obesity.[16] The effects of selective adipose overexpression are more pronounced, with these animals demonstrating symptoms typically seen with the metabolic syndrome.[17]

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is emerging as an important cause of liver disease in India. Epidemiological studies suggest the prevalence of NAFLD in around 9–32% of the general population in India with higher prevalence in those with overweight or obesity and those with diabetes or prediabetes. There is a high prevalence of insulin resistance and nearly half of Indian patients with NAFLD have evidence of full-blown metabolic syndrome. Oxidative stress is involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).[18]

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is considered as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome, which is defined by the presence of central obesity, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertension.[19] The release of fatty acids from dysfunctional and insulin-resistant adipocytes results in lipotoxicity, caused by the accumulation of triglyceride-derived toxic metabolites in ectopic tissues (liver, muscle, pancreatic beta cells) and subsequent activation of inflammatory pathways, cellular dysfunction, and lipoapoptosis. The cross talk between dysfunctional adipocytes and the liver involves multiple cell populations, including macrophages and other immune cells that in concert promote the development of lipotoxic liver disease, a term that more accurately describes the pathophysiology of NASH.

Metformin was first used in medical practice in the 1950s and has been considered the first-line treatment of type 2 diabetes after receiving approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1994. Metformin belongs to a class of insulin sensitizer drugs and acts through reducing hepatic glucose output, increasing insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in peripheral tissue and stimulating fatty acid oxidation in adipose tissue.[20] Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are a class of oral anti-diabetic drugs that induce a nuclear transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), by binding selective ligands.[21] PPAR-γ is predominantly expressed in adipose tissue and leads to decreased hepatic fat content and improves glycemic control with insulin sensitivity. TZDs also increase plasma adiponectin levels, activate AMP-activated protein kinase, and induce fatty acid stimulation.[22] Rosiglitazone which was used like pioglitazone as insulin sensitizing agent in type 2 diabetes has been banned in several countries due to its cardiovascular side effects.[23] Retrospective evaluations have increasingly linked pioglitazone to a higher risk of bladder cancer that appears to be time- and dose-dependent. Pioglitazone remains a medication appropriate for consideration in the management of T2DM; however, clinicians and patients should weigh its risks compared with alternatives, with a regular review of risks.[24]

Treatments that rescue the liver from lipotoxicity by restoring adipose tissue insulin sensitivity (e.g., significant weight loss, exercise, TZDs) or preventing activation of inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress (i.e., Vitamin E, TZDs) hold promise in the treatment of NAFLD, although their long-term safety and efficacy remain to be established.[25] Pioglitazone reverses NASH and improves liver histology by its effect of increasing adiponectin levels.[26] Oxidative stress is believed to play a key role in the pathogenesis of NASH and other liver diseases. Vitamin E is currently the most widely assessed antioxidant. Altered lipid metabolism is thought to be central to the pathogenesis of liver injury in NASH. Therefore, lipid-lowering drugs are attractive therapeutic tools in the treatment of NAFLD.[27]

Present study is done to compare the effects of cardamom with that of pioglitazone, on dexamethasone-induced hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis. Cardamom was as effective as pioglitazone in reducing dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis, and fasting hyperglycemia. The antioxidant and hypolipidemic effects of cardamom may be partially responsible for the beneficial effects. It is concluded that the administration of cardamom or the use of cardamom in diet might be useful in dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis, and fasting hyperglycemia due to glucocorticoids excess.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge sincere thanks to the Department of pharmacology (K.S. Hegde Medical Academy), Nitte University Central Research Laboratory and the staff of animal house for the facilities granted for the research work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus – Present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8:228–36. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paneni F, Costantino S, Cosentino F. Insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16:419. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sailesh KS, Divya, Mukkadan JK. A study on anti-hyper lipidemic effect of oral ad-ministration of cardamom in Wistar albino rats. Narayana Med J. 2013;2:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shalam M, Harish MS, Farhana SA. Prevention of dexamethasone-and fructose-induced insulin resistance in rats by SH-01D, a herbal preparation. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38:419–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma SK, Jain V, Katewa SS. Blood pressure lowering, fibrinolysis enhancing and antioxidant activities of cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2009;46:503–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majdalawieh AF, Carr RI. In vitro investigation of the potential immunomodulatory and anti-cancer activities of black pepper (Piper nigrum) and cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) J Med Food. 2010;13:371–81. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suneetha WJ, Krishnakantha TP. Cardamom extract as inhibitor of human platelet aggregation. Phytother Res. 2005;19:437–40. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad M, Qureshi R, Arshad M, Khan MA, Zafar M. Traditional herbal remedies used for the Treatment of diabetes from district Attock (Pakistan) Pak J Bot. 2009;41:2777–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pushpangadan P, Prakash D. Herbal Nutraceutical Formulation for Diabetics and Process for Preparing the same. US 20060147561 A1. [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 12]. Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/US20060147561 .

- 10.Selyatitskaya VG, Kuz’minova OI, Odintsov SV. Development of insulin resistance in experimental animals during long-term glucocorticoid treatment. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2002;133:339–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1016281501423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:23–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binnert C, Ruchat S, Nicod N, Tappy L. Dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance shows no gender difference in healthy humans. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:321–6. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruzzin J, Wagman AS, Jensen J. Glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscles: defects in insulin signalling and the effects of a selective glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2119–30. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whorwood CB, Donovan SJ, Flanagan D, Phillips DI, Byrne CD. Increased glucocorticoid receptor expression in human skeletal muscle cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2002;51:1066–75. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rask E, Olsson T, Söderberg S, Andrew R, Livingstone DE, Johnson O, et al. Tissue-specific dysregulation of cortisol metabolism in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1418–21. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson JM, Morton NM, Fievet C, Kenyon CJ, Holmes MC, Staels B, et al. Metabolic syndrome without obesity: Hepatic overexpression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7088–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305524101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuzaki H, Paterson J, Shinyama H, Morton NM, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR, et al. A transgenic model of visceral obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Science. 2001;294:2166–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1066285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duseja A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in India – A lot done, yet more required! Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:217–25. doi: 10.1007/s12664-010-0069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh RM, Mohan V. Changing definitions of metabolic syndrome. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:7–12. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.91175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stumvoll M, Nurjhan N, Perriello G, Dailey G, Gerich JE. Metabolic effects of metformin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:550–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yki-Järvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1106–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed MH, Byrne CD. Current treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:188–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chinnam P, Mohsin M, Shafee LM. Evaluation of acute toxicity of pioglitazone in mice. Toxicol Int. 2012;19:250–4. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.103660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee EJ, Marcy TR. The impact of pioglitazone on bladder cancer and cardiovascular events. Consult Pharm. 2014;29:555–8. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2014.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cusi K. Role of obesity and lipotoxicity in the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:711–25e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gastaldelli A, Harrison S, Belfort-Aguiar R, Hardies J, Balas B, Schenker S, et al. Pioglitazone in the treatment of NASH: The role of adiponectin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:769–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musso G, Anty R, Petta S. Antioxidant therapy and drugs interfering with lipid metabolism: Could they be effective in NAFLD patients? Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:5297–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]