Abstract

Nowadays, healthcare systems are challenged by a major worldwide drug resistance crisis caused by the massive and rapid dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and associated emergence of multidrug resistant pathogenic bacteria, in both clinical and environmental settings. Conjugation is the main driving force of gene transfer among microorganisms. This mechanism of horizontal gene transfer mediates the translocation of large DNA fragments between two bacterial cells in direct contact. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) of the SXT/R391 family (SRIs) and IncA/C conjugative plasmids (ACPs) are responsible for the dissemination of a broad spectrum of antibiotic resistance genes among diverse species of Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae. The biology, diversity, prevalence and distribution of these two families of conjugative elements have been the subject of extensive studies for the past 15 years. Recently, the transcriptional regulators that govern their dissemination through the expression of ICE- or plasmid-encoded transfer genes have been described. Unrelated repressors control the activation of conjugation by preventing the expression of two related master activator complexes in both types of elements, i.e., SetCD in SXT/R391 ICEs and AcaCD in IncA/C plasmids. Finally, in addition to activating ICE- or plasmid-borne genes, these master activators have been shown to specifically activate phylogenetically unrelated mobilizable genomic islands (MGIs) that also disseminate antibiotic resistance genes and other adaptive traits among a plethora of pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella enterica.

Keywords: SXT/R391, IncA/C, SGI1, regulation, integrative and conjugative elements, conjugative plasmids, genomic islands, pVCR94

Mobile Genetic Elements in the Modern World of Multiresistance

The discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming over 80 years ago marked the end of the pre-antibiotic era and revolutionized the prevention and treatment of many bacterial infections responsible for high morbidity and mortality. However, Sir Fleming himself warned the scientific community about antibiotic resistance and foresaw that inadequate usage of antibiotics could lead to “educated microbes.” Since then, the use and misuse of antibiotics have led to the rapid and widespread emergence and selection of microorganisms resistant to a wide range of antimicrobial compounds. Today, multidrug resistance (MDR) has become one of the most alarming healthcare issue on a global scale, so much so that in 2014 the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted a bleak short-term future: “A post-antibiotic era—in which common infections and minor injuries can kill—far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st Century” (World Health Organization, 2014).

Point mutations and/or gene amplification can allow bacteria to withstand hostile environments, such as the exposure to antimicrobial compounds (Gorgani et al., 2009; Davies and Davies, 2010; Toprak et al., 2012). Most often, MDR results from the acquisition by horizontal gene transfer of mobile genetic elements carrying multiple antibiotic resistance genes (Burrus et al., 2006; Mulvey et al., 2006; Welch et al., 2007; Escudero et al., 2014). Conjugation, which mediates DNA transfer between two bacterial cells in direct contact, is the most effective mechanism of horizontal gene transfer in terms of host range and quantity of genes translocated to a recipient cell per transfer event (Llosa et al., 2002; de la Cruz et al., 2010). Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) and conjugative plasmids of various incompatibility groups were shown to have a major impact on the global emergence of multidrug resistant pathogenic bacteria, in both clinical and environmental settings (Burrus et al., 2006; Fricke et al., 2009; Smillie et al., 2010; Wozniak and Waldor, 2010; Guglielmini et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2011; Carattoli, 2013). Although both types of elements transfer from cell to cell by conjugation, their mechanism of persistence in the bacterial host cell genome is different. On the one hand, ICEs maintain themselves by integration into the chromosome of their host and excise prior to transfer as circular molecules (Burrus et al., 2002; Burrus and Waldor, 2004; Wozniak and Waldor, 2010). On the other hand, conjugative plasmids are maintained by replication as episomes, i.e., DNA molecules that are distinct from the chromosome.

This review focuses on the regulatory networks that govern the conjugative transfer of ICEs belonging to the SXT/R391 family (SRIs) and conjugative plasmids of the A/C incompatibility group (ACPs). Both classes of elements bear highly similar and nearly syntenic core sets of conserved genes and code for comparable transfer activator complexes (Wozniak et al., 2009; Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). Recent investigations of the regulatory circuitries that activate SRIs and ACPs transfer have also contributed to the discovery of three classes of genomic islands (GIs) specifically mobilized by either SRIs or ACPs (Doublet et al., 2005; Daccord et al., 2010, 2012; Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

Diversity and Prevalence of SRIs and ACPs

SRIs and ACPs are major contributors to worldwide dissemination of adaptative traits such as antibiotic resistance among several species of Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae of clinical origin or isolated from the aquatic environment.

The SXT/R391 family is one of the largest, diverse and well-studied set of ICEs among Gram-negative bacteria. Extensive experimental and bioinformatic studies have led to a deeper understanding of their prevalence, diversity, and evolution (Boltner et al., 2002; Wozniak et al., 2009; Garriss and Burrus, 2013; Carraro and Burrus, 2014; Spagnoletti et al., 2014). SRIs are large conjugative elements (79 to 110 kb) found integrated into the 5′ end of prfC in the chromosome of several species of Vibrio, Photobacterium, Providencia, Proteus, Alteromonas, Marinomonas, and Shewanella, and are easily transferred to E. coli in the laboratory (Coetzee et al., 1972; Waldor et al., 1996; Hochhut and Waldor, 1999; Beaber et al., 2002a; Pembroke and Piterina, 2006; Osorio et al., 2008; Harada et al., 2010; Rodriguez-Blanco et al., 2012; Badhai et al., 2013; Lopez-Perez et al., 2013; Spagnoletti et al., 2014). Notably, SRIs played a key role in the dissemination of MDR in the seventh-pandemic lineage of V. cholerae, the etiological agent of the diarrhoeal disease cholera (Spagnoletti et al., 2014). V. cholerae is endemic in Asia, Africa, and Central America and epidemics of cholera are usually blooming in locations where the sanitation infrastructures and access to clean water are compromised. Indeed, cholera is considered by the WHO as an indicator of sanitation mismanagement and humanitarian crisis (e.g., refugee camps). Currently, most clinical isolates of V. cholerae carry an SRI and are multidrug resistant worldwide. Most SRIs found in epidemic strains of V. cholerae contain the genes floR, strBA, sul2, and dfrA1 or dfr18, respectively conferring resistance to florfenicol/chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (Waldor et al., 1996; Hochhut et al., 2001; Wozniak et al., 2009). Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim have synergistic antibacterial activities and are often used in combination for the treatment of cholera (Kaper et al., 1995). Other SRIs from the aquatic environment and from diverse pathogens confer resistance to kanamycin (aph) or tetracycline (tetAR) (Coetzee et al., 1972; Osorio et al., 2008; Wozniak et al., 2009; Bi et al., 2012). In the countries where the sanitation infrastructures are appropriate, the domestic cases of cholera and other vibriosis caused by hosts of SRIs are widely associated with the consumption of raw or undercooked seafood (Morris, 2003; Song et al., 2013; Hara-Kudo and Kumagai, 2014; Robert-Pillot et al., 2014). For instance, a few cases of cholera acquired in the US are declared each year. These sporadic cholera cases are generally attributed to consumption of seafood gathered from the US Gulf coast (Loharikar et al., 2015). Antibiotic resistance genes carried by SRIs are also troublesome for aquaculture as resistance genes can hinder the treatment of diseased fish and enter the food chain (Osorio et al., 2008; Rodriguez-Blanco et al., 2012; Nonaka et al., 2014). Indeed, consumption of raw fish and shellfish contaminated by live bacteria bearing SRIs could facilitate the dissemination of MDR among Gammaproteobacteria of the human host microbiome.

ACPs are large (>110 kb) circular plasmids grouped as a family based on the high percentage of sequence conservation of their repA gene, which codes for their replication intiator protein (Llanes et al., 1994, 1996; Carattoli et al., 2005; Fricke et al., 2009). Multidrug resistant ACPs are found worldwide in pathogens associated with human infections such as Citrobacter freundii, V. cholerae, Salmonella enterica, Proteus mirabilis, E. coli, Yersinia pestis and ruckeri, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Providencia stuartii (Bauernfeind et al., 1996; Galimand et al., 1997; Giles et al., 2004; Welch et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2008; Fricke et al., 2009; Call et al., 2010; Fernandez-Alarcon et al., 2011; Lindsey et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2011; Carattoli, 2013; Carraro et al., 2014b; Rahman et al., 2014). ACPs carrying MDR are also increasingly encountered in enteropathogenic bacteria recovered from food-producing animals and food products, mainly S. enterica and E. coli (Glenn et al., 2011; Lindsey et al., 2011; Randall et al., 2011; Folster et al., 2012; Del Castillo et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2014). Disturbingly, recent studies identified multiple extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs)-encoding ACPs conferring resistance to a wide range of β-lactam antimicrobials (Fernandez-Alarcon et al., 2011; Folster et al., 2011, 2012; Walsh et al., 2011; Harmer and Hall, 2015). Carbapenems were the last effective β-lactams for the treatment of infectious bacteria carrying ESBLs. Unfortunately, several recently isolated ACPs propagate the infamous New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase blaNDM-1 gene and its variants, which code for zinc metallo-β-lactamases that hydrolyze all penicillins, cephalosporins and carbapenems (Walsh et al., 2005, 2011; Yong et al., 2009; Nordmann et al., 2011; Tijet et al., 2015).

ACPs and SRIs are a threat to antibiotic therapies due to the large variety of antibiotic resistance genes that they bear on dynamic genetic structures such as integrons and transposons, further promoting the exchange and capture of resistance genes from other mobile genetic elements (Hochhut et al., 2001; Mazel, 2006; Welch et al., 2007; Fricke et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2009; Lindsey et al., 2011; Carraro et al., 2014b). Acquisition and exchange of antibiotic resistance genes are strongly enhanced by the broad host range of these elements, which can easily spread across several genera and species of Gammaproteobacteria. This phenomenon is likely further exacerbated by their mechanism of transfer as single-stranded DNA molecules have been shown to stimulate the SOS response in recipient cells, thereby promoting the intra- and inter-integrons movement of resistance cassettes (Guerin et al., 2009; Baharoglu et al., 2010, 2012; Cambray et al., 2011; Escudero et al., 2014).

Modular Organization of SRIs and ACPs

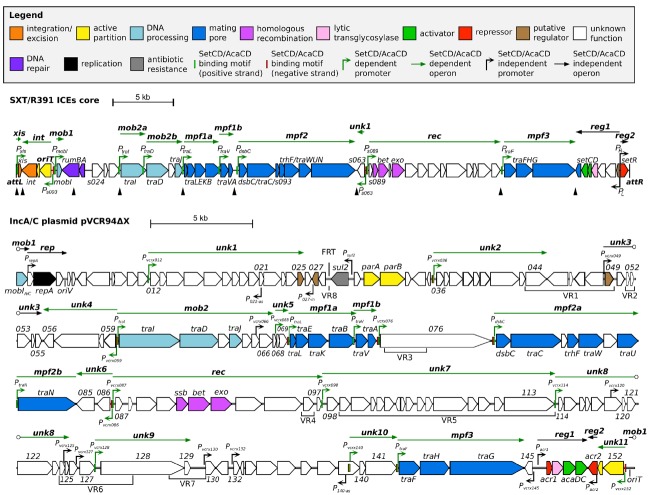

All SRIs share 47 kb of DNA corresponding to a highly conserved core set of 52 genes with over 95% identity at the nucleotide level (Wozniak et al., 2009). About half of these genes have been shown to be essential to ensure the basic maintenance, transfer and regulatory functions of SRIs. These essential genes are clustered in four main modules (Figure 1), i.e., the int module which codes for the integrase and excisionase and ensures intracellular mobility, the mob and mpf modules which code for a type IV secretion system (T4SS) and is responsible of the intercellular mobility (DNA processing and mating pore formation), and the reg module coding for the regulatory network governing the expression of the other modules. Each module can contain one to several transcriptional unit(s) (Figure 1; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). The reg module of SRIs is the most highly conserved locus amongst members of this family of ICEs (Wozniak et al., 2009).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the genetic organization and transcriptional units of the conserved core of SXT/R391 ICEs (integrated in prfC) and pVCR94ΔX (circular map linearized at the start position of gene mobI) adapted from Poulin-Laprade et al. (2015) and Carraro et al. (2014a, 2015a). Genes are represented by arrows and color coded according to their function as indicated in the legend. For clarity, ORF names vcrxXXX were shortened as XXX for pVCR94ΔX. SetCD- and AcaCD-binding motifs located on positive and negative DNA strands are represented by light green and red narrow boxes, respectively. Operons are indicated by arrows positioned above represented genes. SetCD- and AcaCD-regulated promoters and operons are colored in green. Open circles mark operons interruptions generated by the map format. mob1-2, DNA processing; rep, replication; unk1-11, unknown; mpf1-3, mating pore formation; rec, recombination; reg1-2, regulation. P021–as and P140–as: vcrx021 and vcrx140 antisens promoters, respectively. P027–in: vcrx027 internal promoter. Black triangles show the position of variable cargo DNA in SRIs, while variable DNA regions inserted in the conserved core of ACPs are indicated below genes (VR1 to VR8). The origin of replication (oriV) and the origin of transfer (oriT) are indicated. The position of the FRT site resulting from the deletion of the antibiotic resistance gene cluster in pVCR94 is also shown.

ACPs are characterized by ∼110 kb of conserved core genes with over 98% nucleotide sequence identity (Fricke et al., 2009; Fernandez-Alarcon et al., 2011; Del Castillo et al., 2013; Carraro et al., 2014b; Harmer and Hall, 2014, 2015). Although ACP conserved core is larger than the one shared by SRIs, their organization is highly similar and syntenic (Welch et al., 2007; Wozniak et al., 2009). In particular, the tra genes of the mob and mpf modules of ACPs and SRIs are reminiscent of the IncFI F and IncHI1 R27 plasmids suggesting a common ancestry (Lawley et al., 2003). One of the most striking differences between SRIs and ACPs reflects their respective biology. The int module, which ensures chromosomal integration and excision of SRIs, is replaced by the rep module driving the replication of the episomal ACPs. The conserved core of ACPs also contains several genes of unknown functions beyond those also found in SRIs.

Distinctive features of the individual members of SRI and ACP families are provided by insertions of variable cargo DNA in hotposts dispersed in their respective conserved core. These insertions vary in size (from ∼60 to 20,000 bp) and encode adaptative traits that may provide a selective advantage to the bacterial host in specific conditions, such as resistance to antibiotics, heavy metals or phage infection, or synthesis of the second messenger c-di-GMP (Welch et al., 2007; Fricke et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2009; Bordeleau et al., 2010; Carraro et al., 2014a).

Control of the Conjugative Functions of SRIs and ACPs

Control of SRI and ACP conjugative transfer is a key attribute for their propagation and stability. Excessive repression would impair their dissemination, while overactivation would be a burden for the bacterial host causing reduced fitness, and ultimately their instability in the cell population (Lundquist and Levin, 1986; Scott et al., 1988; Beaber et al., 2002b; Ramsay et al., 2006; Bellanger et al., 2009; Haft et al., 2009). Moreover, SRIs and ACPs not only drive their self-transfer, but also the transfer of phylogenetically unrelated mobilizable genomic islands (MGIs). Additionally, SRIs in association with MGIs can mobilize up to 1.5 Mb of chromosomal DNA each in Hfr-like conjugal events initiated prior to their excision (Hochhut et al., 2000; Daccord et al., 2010). Hence, these elements can potentially mobilize more than 60% of V. cholerae chromosome I in a single conjugal event.

Transcriptional repressors encoded by SRIs and ACPs repress the expression of master activator genes, maintaining these elements in a quiescent state in most cells of the bacterial population. Both SRIs and ACPs thrive in a large array of Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae, which implies that their regulatory networks are likely autonomous and orthogonal, i.e., they allow the activation/repression of the element while avoiding crosstalks with regulatory networks of the host cell.

The Regulation Module of SRIs and ACPs

SRIs and ACPs bear distinct regulatory modules that govern their self-transmissibility (Figure 2). These regulatory modules code for unrelated repressors: SetR for SRIs and Acr1 and Acr2 for ACPs (Beaber et al., 2004; Carraro et al., 2014a). In contrast, the regulatory module of SRIs and ACPs code for related transcriptional activator complexes, respectively SetCD and AcaCD, that drive the expression of the conjugative genes and other functions (Beaber et al., 2002b; Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). SetCD and AcaCD are distant relatives of FlhCD, the master activator of flagellum biosynthesis in many Gram-negative bacteria (Chevance and Hughes, 2008; Fitzgerald et al., 2014). Recent studies established the AcaCD and SetCD regulons and refined the models of transcriptional organization of the functional core of both types of elements (Figure 1; Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the regulatory modules of SXT/R391 ICEs (SRI) and IncA/C plasmids (ACP). The genes are color-coded as indicated in Figure 1 legend. Numbers between the elements represent the percentage of identity between orthologous proteins. The regulation exerted by SetR, Acr1, and Acr2 is indicated (minus sign for repression, plus sign for activation). For clarity, ORF names s0XX were shortened as XX for SRI and vcrxXXX as XXX for ACP.

Repression of SRIs Dissemination

The SetR Repressor

The dominant regulatory state of SRIs is the quiescent state in which the element is integrated into the chromosome and the genes associated with recombination and transfer are silent (Beaber et al., 2004; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). In this dormant state, very few genes are transcribed, including genes independently regulated belonging to cargo DNA (e.g., antibiotic resistance genes) and setR. The setR gene is located at the rightmost end of the integrated ICE (Figure 1). SetR is an acronym for SXT excision and transfer repressor. setR mRNA transcript is leaderless, expressed from the PR promoter, and codes for a 215-amino acid residue protein with a DNA binding helix-turn-helix motif (HTH_3, PF01381) in its N-terminal moiety and a C-terminal LexA-like autoproteolysis motif (Peptidase_S24, PF00717). SetR shares homology with λ CI-like repressors encoded by lambdoid bacteriophages (Beaber et al., 2002b). The pivotal role of SetR in SRIs regulation is reflected by the inability to generate a setR mutant of SXT without simultaneous setR trans-complementation or a preexisting setCD inactivation (Beaber et al., 2002b, 2004).

SetR Regulation of the PL and PR Early Promoters

SetR maintains the quiescent integrated state of SRIs by binding to four operator sites (OL, O1, O2, and O3) distributed in the intergenic region between s086 and setR (Figure 2; Beaber and Waldor, 2004). Footprint assays revealed that the relative affinity of SetR for its operators is O1 > O2≈O3 > OL (Beaber and Waldor, 2004). SetR operator sites bear partial dyad symmetry and are separated by AT-rich spacers. An additional site located 800 bp downstream of the PL promoter was suggested but never assessed (Beaber and Waldor, 2004). It has been proposed that binding of SetR to the four operators between s086 and setR leads to SetR’s autoregulation of the PR promoter (Beaber et al., 2004). Binding of SetR to O1 is thought to lead to activation of the PR promoter. When the cellular pool of SetR exceeds a threshold, SetR is thought to repress its own expression by further binding to the low affinity O3 operator, concealing the -10 element of the PR promoter (Beaber and Waldor, 2004). Beaber and Waldor (2004) observed the repressive effect of SetR on PR by monitoring the β-galactosidase activity of a PR-lacZ transcriptional fusion in strains containing or lacking SXT, or its ΔsetCD or ΔsetCD ΔsetR mutants. Quantification of the β-galactosidase activity in these strains showed that the presence of SXT lowered the activity of PR by 30% (SXT– versus SXT+) (Beaber and Waldor, 2004). Deletion of setCD did not significantly alter PR activity compared to the SXT+ background, whereas in cells containing SXT ΔsetCD ΔsetR, PR activity was comparable to cells lacking SXT, thereby confirming that SetR represses PR (Beaber and Waldor, 2004). SetR binding to O1 and OL obstructs the PL promoter which drives setCD expression and subsequent activation of conjugative functions.

The mRNA transcript starting at PL codes for seven proteins including a predicted λ Cro-like repressor, the two subunits of the activator complex SetCD, and the entry exclusion determinant Eex (Figure 2; Beaber et al., 2002b; Beaber and Waldor, 2004; Marrero and Waldor, 2005; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

Alleviation of SetR Repression

In donor cells, the inductive cue triggering SRI propagation is linked to the SOS response (Waldor et al., 1996; Beaber et al., 2004). Using the energy of ATP, RecA polymerizes onto single-stranded DNA, generating RecA-ssDNA filaments (RecA*) that are competent for homologous recombination and are also allosteric effectors unleashing the latent proteolytic activity of LexA and λ CI-like repressors (Little, 1984; Chen et al., 2008). Thus, RecA is the central factor linking DNA damages (sometimes caused by antibiotics) to the cellular SOS stress response (DNA mutagenesis and repair), and to the induction of conjugative transfer of SRIs that are major vectors of MDR (Beaber et al., 2004; Baharoglu et al., 2010). Inspired by the extensive work done on the λ CI repressor, the link between RecA* and SetR was drawn with the mutant setRG49E in which the Ala-Gly cleavage site activated by RecA is disrupted (Gimble and Sauer, 1985; Beaber et al., 2004). As expected, the setRG49E mutant of SXT is unresponsive to mitomycin C, a DNA damaging agent known to trigger the bacterial SOS response.

Upon DNA damage, SetR becomes a substrate for RecA*-mediated self-cleavage, thereby alleviating SetR’s repression on PL and allowing setCD expression. The -10 and -35 promoter elements of PL are more similar to the recognition motif of σ70-bound RNA polymerase (RNAP) than those of PR, likely leading to a quicker isomerization into an open complex competent for transcription initiation. Alleviation of SetR repression would then be sufficient for recognition of PL by RNAP, without the need of a transcriptional activator. This model is reminiscent of the regulation of λ PR and PRM early promoters (Strainic et al., 2000; Ptashne, 2004).

SetR acts as a sentinel “sensing” DNA damages and triggering the “escape” of SRIs to recipient cells. For an optimal responsiveness and avoidance of cellular resources misallocation, SetR expression is tightly regulated and maintained at low levels (Beaber and Waldor, 2004). The setR transcript is a leaderless mRNA; the absence of a Shine-Dalgarno sequence is a post-transcriptional mechanism that likely contributes to a low intracellular level of SetR protein (Van Etten and Janssen, 1998; Beaber and Waldor, 2004). Spontaneous induction of the SOS response in a subpopulation of cells is thought to account for the low basal transfer of SRIs, which varies between individual SRIs for reasons that remain unknown (Beaber and Waldor, 2004; McCool et al., 2004; McGrath et al., 2005; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

Repression of ACPs

While no SetR homolog has been found in ACPs, their regulatory module codes for two repressors named Acr1 and Acr2 (IncA/C repressor 1 and 2; Carraro et al., 2014a). acr1 codes for a 90-amino acid Ner-like protein that is mainly composed of a helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain (HTH_35, PF13693). Acr1 directly represses its own expression from the constitutive promoter Pacr1 (Figure 2). This promoter drives the expression of acr1 and also the expression of acaC and acaD, which code for the activator complex AcaCD. Acr2 is a 139-amino acid H-NS-like repressor (Histone_HNS, PF00816) that also directly represses Pacr1 (Carraro et al., 2014a,b). H-NS proteins are known to globally repress expression of horizontally acquired DNA by binding AT-rich sequences (Dorman, 2004, 2014; Navarre et al., 2006). Besides Pacr1, Acr2 might also repress other plasmid- or host-borne promoters, potentially having a wider impact on the biology of ACPs and their interaction with host cells.

The frequency of transfer of ACPs varies widely from non detectable to very high (1 in 10 cells for pVCR94; Welch et al., 2007; Fricke et al., 2009; Carraro et al., 2014b). Inducing factors triggering the conjugative transfer of ACPs have yet to be identified (Carraro et al., 2014a,b). Consistent with the absence of SOS-dependent repressors such as λ CI or ImmR, conjugative transfer of ACPs is independent of recA and the SOS response (Auchtung et al., 2005; Carraro et al., 2014b).

The Heteromeric Complexes SetCD and AcaCD

It was previously established that individual deletion of either setC or setD abolished the excision and transfer of the prototypical SRI SXT (Beaber et al., 2002b). These deletions were complemented in trans with plasmids expressing the individual genes, thereby confirming the central role of SetC and SetD in the biology of SRIs. Transcriptional lacZ fusions with promoters driving the expression of int, traL and traG demonstrated that SetCD is a transcriptional activator of the site-specific recombination and conjugative transfer genes (Beaber et al., 2002b; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

A similar characterization was recently carried out for acaC and acaD, which code for the master activator of ACP conjugative transfer (Carraro et al., 2014a). For both sets of transcriptional activators, genetic assays strongly suggest that the products of the setD-setC and acaD-acaC genes assemble into higher order protein complexes designated SetCD and AcaCD, respectively. While no direct experimental evidence support the oligomerization of SetCD, AcaD was shown to copurify with 6xHis-tagged AcaC subunit, supporting the formation of heteromeric complexes as observed for the flagellar gene activator complex FlhCD (Wang et al., 2006; Carraro et al., 2014a).

Conflicting evidence suggest a possible autoregulation of SetCD expression. On the one hand, overexpression of SetCD was reported to result in a 40-fold activation of expression of a chromosomal setD::lacZ fusion in SXT (Beaber et al., 2002b). On the other hand, expression from PL, which drives setCD expression, remained unaffected by deletion of setCD regardless of the presence of mitomycin C (Beaber et al., 2004). An exhaustive list of the promoters targeted by SetCD was recently established for three representative members of the SRI family (SXT, R391 and ICEVflInd1) using chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with exonuclease digestion (ChIP-exo) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). No SetCD binding site was found upstream of PL or elsewhere in the regulatory module.

A similar experimental approach also allowed to establish the list of the promoters targeted by AcaCD in pVCR94ΔX, a prototypical ACP lacking most of its resistance genes (Carraro et al., 2014a,b). The DNA motifs recognized by SetCD and AcaCD were deduced from the multiple targets that were experimentally determined. Operator sites for SetCD and AcaCD fixation greatly differ from each other, and from the DNA motif recognized by E. coli FlhCD (Figure 3A; Carraro et al., 2014a; Fitzgerald et al., 2014; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). Despite their functional homology, SetCD, AcaCD, and FlhCD exhibit a high degree of divergence, which is reflected in their respective DNA target preference and specificity (Liu and Matsumura, 1994; Carraro et al., 2014a; Fitzgerald et al., 2014; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

FIGURE 3.

Activation by heteromeric complexes SetCD and AcaCD. (A) Experimentally determined recognition motifs of SetCD and AcaCD (Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). (B) Representation of SetCD targets in SRIs and in MGIs they mobilize. The arrows indicate transcriptional repression by SetR (minus sign) and transcriptional activation by SetCD (plus signs). (C) Representation of AcaCD targets in ACPs and in MGIs from MGIVmi1 and SGI1 families. The arrows indicate transcriptional repression by Acr1 and Acr2 (minus sign) and transcriptional activation by AcaCD (plus signs). In both B and C panels, the modules of DNA processing (mob) and mating pair formation (mpf) are indicated and color-coded as described in Figure 1 legend.

SetCD and AcaCD are Pleiotropic Transcriptional Activators

In many mobile genetic elements, genes involved in a given biological function are often arranged in an operon structure within a single module expressed from a single promoter (Celli and Trieu-Cuot, 1998; Toussaint and Merlin, 2002; Auchtung et al., 2005; Carraro et al., 2011). The genes coding for the conjugative machinery of the E. coli IncF1 F plasmid or the Enterococcus faecalis ICE Tn916 are good examples of such an organization (Celli and Trieu-Cuot, 1998; Lawley et al., 2003). In contrast, the conjugation modules of SRIs and ACPs are fragmented in multiple and distinct operons (Figures 1 and 3B,C). This fragmentation of functional modules is most often attributed to insertions of variable cargo DNA, insertion sequences (IS) and transposons (Fricke et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2009; Fernandez-Alarcon et al., 2011; Meinersmann et al., 2013). These insertions occur in sites most likely selected because of their minimal impact on genes essential for transfer and subsequent maintenance of SRIs and ACPs in bacterial populations. Discontinuity of the functional modules complexifies the genetic regulation in terms of timing and gene dosage for coordinated expression of their functions allowing the dissemination of SRIs and ACPs. The efficient activation of the machinery for DNA processing and mating pore assembly relies on the flexibility and accuracy of DNA binding by the activator complexes SetCD and AcaCD. For instance, SetCD can be tolerant to insertion of cargo DNA in the promoter driving expression of traI in SXT, an essential component of conjugal transfer (Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

Mechanism of Activation by SetCD and AcaCD

ChIP-exo experiments have revealed 11 SetCD-dependent promoters in SRIs and 19 AcaCD-dependant promoters in ACPs (Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). SetCD- and AcaCD-dependent promoters have poorly conserved -10 and non-conserved -35 boxes, compared to the canonical σ70 promoter elements (Hawley and McClure, 1983; Kumar et al., 1993). In each promoter, the DNA motif recognized by the activator complex partially overlaps the -35 element, which is usually bound by the σ70 subunit of RNAP (Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). This suggests that, as observed for FlhCD, SetCD and AcaCD compensate for the lack of a recognizable -35 elements by binding in the -35 region, facilitating the recruitment of σ70-bound RNAP to the promoters. As such, FlhCD, SetCD and AcaCD act as typical class II transcriptional activators (Browning and Busby, 2004). FlhCD was shown to interact with the C-terminal domain of RNAP (Liu et al., 1995). Biochemical characterizations are needed to establish whether AcaCD and SetCD directly interact with RNAP.

Activation of Integration, Excision, and Stability Functions

As SRIs maintain by integration in the host cell chromosome, the major contributor to their maintenance in a bacterial lineage is the integration/excision module (Hochhut and Waldor, 1999; Burrus and Waldor, 2003). This module contains the int gene coding for the integrase, a site-specific tyrosine recombinase, the xis gene coding for a recombination directionality factor, as well as their cognate attachment sites, i.e., attP on the circular form, or attL and attR at both ends of the chromosomally integrated SRI. Expression of both int and xis is SetCD-dependent, yet driven from two separate promoters (Burrus and Waldor, 2003; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). Stability of SRIs is also provided by toxin-antitoxin systems (TA) and a type II active partition system named srpRMC (SXT/R391 partition; Dziewit et al., 2007; Wozniak and Waldor, 2009; Carraro et al., 2015b). The srpRM genes code for the proteins driving the active partition of the excised element in daughter cells, while srpC is a centromere-like sequence bound by SrpR (Baxter and Funnell, 2014; Carraro et al., 2015b). Regulation of integration, excision and active partition of SRIs are interconnected as srpRM and int are cotranscribed from the same SetCD-dependent promoter (Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

As plasmids, ACPs maintain in bacterial lineages by autonomous replication, which is mediated by the repA/oriV locus in an AcaCD-independent fashion (Llanes et al., 1996; Carraro et al., 2014a). Orthologs of the SRI’s srpRM genes are also found in ACPs (vcrx151/vcrx152 in pVCR94). Reminiscent of SRIs, expression of these srpRM orthologs is AcaCD-dependent (Carraro et al., 2014a). Interestingly, ACPs also carry genes coding for a type I ParABC-like partitioning system (Walker-type ATPase; vcrx031/vcrx032 in pVCR94), whose regulation is likely independent of AcaCD (Baxter and Funnell, 2014; Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015b).

Activation of the Conjugative Machinery

SRIs and ACPs code for very similar conjugative machineries, as reflected by the syntenic organization of their transfer genes and the closely related proteins they encode (Fricke et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2009). The mobilization modules (mob) code for key factors involved in DNA molecule preparation (DNA processing functions) that will be translocated to the recipient cell through the type IV secretion system encoded by the tra modules. The relaxase TraI, with the help of the auxiliary protein MobI, is thought to recognize the origin of transfer (oriT) located immediately upstream of mobI in both SRIs and ACPs (Figures 1 and 3B,C; Ceccarelli et al., 2008; Carraro et al., 2014b). By analogy with other better characterized conjugative systems such as F, the resulting nucleoprotein complex, aka relaxosome, is thought to nick one DNA strand within oriT (Llosa et al., 2002). This DNA strand is delivered to the mating pore linking the donor and recipient cells. Based on the mechanism of single-stranded conjugative transfer of the F plasmid, it is assumed that SRIs and ACPs replicate using the rolling-circle mechanism during translocation of the transferred DNA strand. Several studies on ICEs from both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria showed that ICEs are capable of intracellular rolling-circle plasmid-like replication (Kiewitz et al., 2000; Pembroke and Murphy, 2000; Dimopoulou et al., 2002; Grohmann, 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Carraro et al., 2011, 2015b; Sitkiewicz et al., 2011). This replication only occurs in a subpopulation of cells as it is conditional on element activation. Mechanistically, it does not strikingly differ from rolling-circle replication used for the stable maintenance of plasmids, uses oriT as an origin of replication and the relaxase TraI as a replication initiator protein. In fact, the replication module is part of the mobilization module (Grohmann, 2010; Lee et al., 2010; Carraro and Burrus, 2014). Although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated, SRIs have been shown to replicate in an oriT, TraI and SetCD-dependent manner (Pembroke and Murphy, 2000; Carraro et al., 2015b).

Genome-wide footprinting of SetCD and AcaCD DNA binding coupled with transcriptomic analyses revealed that the syntenic mob modules of SRIs and ACPs are divided into different transcriptional units (Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). In SRIs, SetCD binds upstream of mobI (mob1), traI (mob2a), and traDJ (mob2b). Interestingly, the canonic promoter driving the expression of traI is disrupted by an insertion into hotspot 5 (Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). The -10 element of PtraI is part of the conserved core and retained, while the -35 element is variable and provided by inserted cargo DNA. Alteration of PtraI is associated with a poorer affinity for SetCD as determined by ChIP-exo, which could contribute to the lower transfer and replication of SXT compared with R391 (Carraro et al., 2015b; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). In ACPs, AcaCD activates the expression of traIDJ (mob2) from a unique promoter (Figure 1; Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a). No ACPs available to date in the Genbank database harbor a PtraI promoter altered by insertion of cargo DNA (Carraro et al., 2014a). Surprisingly, no AcaCD binding-site was detected upstream of mobIA/C (formerly known as vcrx001, Carraro et al., 2014a,b). As for MobI of SRIs, MobIA/C is essential for conjugative transfer of ACPs (Carraro et al., 2014b). The impact of such subtle differences on the regulation of conjugative transfer of SRIs and ACPs need to be experimentally addressed. Altered regulation of the mob functions can have drastic effects on the dynamics of these elements since initiation of transfer (oriT recognition and nicking by the relaxosome) was shown to be the rate limiting step of SRIs dissemination (Carraro et al., 2015b).

Other essential components for conjugative transfer of SRIs and ACPs are the pilus, which stabilizes the initial contact between cells, and the type IV secretion system (mating pore) through which DNA is translocated to recipient cells. This conjugative machinery is encoded by three mating pair formation modules (mpf) which are, as the mob modules, syntenic between SRIs, ACPs and the F plasmid (Figure 1; Lawley et al., 2003; Fricke et al., 2009; Wozniak et al., 2009). In both SRIs and ACPs, the mpf1a module contains the traLEKB genes, while traAV are found in mpf1b (Figure 1; Armshaw and Pembroke, 2013; Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). The mpf2 modules are organized differently in SRIs (mpf2: dsbC-traC-s093-trhF-traWUN) and ACPs (mpf2a: dsbC-traC-vcrx079-trhF-traW-vcrx082-traU and mpf2b: traN in pVCR94ΔX), the latters expressing traN from its own AcaCD-dependent promoter (Figures 3B,C). Finally, the mpf3 module (traFHG) has the same operon structure in both types of elements.

SetCD targets were exclusively found in the conserved backbone of SRIs (Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). In contrast, AcaCD binding sites were also detected upstream of operons containing genes of unknown functions, as well as in regions that are not conserved (Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a). The relevance of these AcaCD-regulated genes for the biology of ACPs remains to be determined.

Activation of RecA-independent Homologous Recombination Functions

In addition to conjugative transfer functions, SRIs and ACPs code for diverse mutagenic and recombination functions. Both types of elements include the well-conserved bet and exo genes, which code for a λ Red-like RecA-independent homologous recombination system (Garriss et al., 2009). This system contributes to the formation of hybrid ICEs by recombineering elements inserted in tandem in the chromosome, generating new patterns of antibiotic resistance genes. In both SRIs and in ACPs, the expression of bet and exo is under the control of the SetCD- and AcaCD-dependent Ps089 and Pvcrx087 promoters, respectively (Garriss et al., 2013; Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). In both cases, the promoter driving their expression exhibits the highest ChIP-exo enrichment peaks. Although bet and exo are highly transcribed, their expression is hindered by a strong translational attenuator located upstream of bet in SXT (Garriss et al., 2013). This translational attenuator is also present in ACPs, but its functionality remains to be investigated.

SetCD and AcaCD Trigger the Expression of Genomic Island-bound Genes

Several autonomous conjugative elements were shown to mobilize non-autonomous GIs using various mechanisms (Bellanger et al., 2014). For instance, the conjugative transposon Tn916 trans-mobilizes the 1.7 kb-GI mTnSAG1 from Streptococcus agalactiae by recognition of a cryptic oriT located within the lnu(C) gene, which confers resistance to lincomycin (Achard and Leclercq, 2007). ICEs from Streptococcus thermophilus were shown to cis-mobilize elements called CIMEs (cis-mobilizable elements) by a mechanism designated as accretion-mobilization (Pavlovic et al., 2004; Bellanger et al., 2011). SRIs and ACPs can also trans-mobilize diverse GIs using distinct strategies for their dissemination. Interestingly, these strategies are all coupled to the regulatory network of their cognate helper element (Daccord et al., 2010, 2012, 2013; Douard et al., 2010; Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015).

SRIs-dependent Mobilization of Genomic Islands

Characterization of the oriT sequence of SRIs allowed identification of chromosomal oriT-like sequences that were more than 63% identical (Ceccarelli et al., 2008; Daccord et al., 2010). Further investigations revealed that these cryptic oriT sequences belong to MGIs integrated at the 3′ end of yicC in the chromosome of Vibrio, Alteromonas, Pseudoalteromonas, and Methylophaga species (Daccord et al., 2010, 2013). The size of these MGIs ranges from 18 to 33 kb with a conserved core sequence of ∼5.5 kb encompassing four genes (intMGI, cds4, cds8, rdfM) and their cognate regulatory sequences. intMGI and rdfM code for the integrase and recombination directionality factor that allow MGIs to excise from and integrate into the host cell chromosome. Function of cds4 and cds8 remains unknown. The conserved backbone of MGIs is disrupted by DNA fragments that vary in size and gene content. Most of these genes code for adaptive functions such as type I and type III restriction-modification system that may confer resistance to bacteriophage infection (Daccord et al., 2013).

The initial step of an MGI mobilization by SRIs is its excision from the chromosome. Excision requires the transcriptional activation of intMGI and rdfM by the SRIs-encoded master activator SetCD (Figure 3B), and the subsequent recombination between the attLMGI and attRMGI attachment sites flanking the MGI (Daccord et al., 2012; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). The resulting circular extrachromosomal MGI carries oriTMGI, which acts as a cis-acting sequence that mimics the oriT of SRIs and hijacks the relaxosome encoded by SRIs. Ultimately, the MGI is translocated to the recipient cell throught the mating apparatus encoded by SRIs. Once in the recipient cell, the MGI becomes completely independent of the helper SRI and its transcriptional activator SetCD to establish itself in the new host. The MGI constitutively expresses intMGI at a low level, thereby allowing its own integration into the 3′ end of yicC (Daccord et al., 2012). MGIVflInd1, initially isolated from Vibrio vulnificus, was used as a prototype to study MGIs and was reported to be mobilized at high frequency between E. coli strains by both ICEVflInd1 and SXT (10-3 transconjugants per donor cell). This frequency rose to 10–1 transconjugants per donor cell upon overexpression of setCD or induction with mitomycin C treatment (Daccord et al., 2010, 2012). MGIVflInd1 is also able to cis-mobilize over 1 Mb of chromosomal DNA located 5′ of yicC in an Hfr-like manner (Daccord et al., 2010). Chromosomal DNA mobilization by MGIVflInd1 involves initiation of transfer at oriTMGI by the relaxosome of a SRI prior to excision of the MGI from the chromosome.

ACP-dependent Mobilization of Genomic Islands

Discovery of the sequences targeted by AcaCD in ACPs was the cornerstone for the identification of potential chromosomal targets in genomes of several Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae (Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a). Notably, multiple AcaCD binding sites were detected in the Salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI1), which confers MDR to pathogenic S. enterica and was reported to be mobilized in trans by ACPs by an unknown mechanism (Doublet et al., 2005; Douard et al., 2010; Carraro et al., 2014a). AcaCD sites were also detected in other GIs that are or could be mobilized by ACPs (Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a).

SGI1-like Elements

SGI1 is a 43-kb chromosomal mobile element carrying a class 1 integron that confers resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides and tetracycline (ACSSuT phenotype; Mulvey et al., 2006). SGI1 and related MDR-conferring GIs have been found integrated at the 3′ end of thdF (trmE) in a large variety of multidrug resistant S. enterica serovars and in P. mirabilis (Boyd et al., 2008; Wiesner et al., 2009; Hall, 2010; Girlich et al., 2015). All SGI1-like elements share a highly conserved ∼27 kb core region, which mostly contain genes of unknown function (Mulvey et al., 2006; Boyd et al., 2008). The conserved genes int and xis mediate SGI1’s excision from and integration into the chromosome (Doublet et al., 2005). Three conserved tra genes code for putative mating pore components sharing 40, 60, and 78% identity with ACP’s TraN, TraG and TraH, respectively. In most SGI1-like elements, the core region is disrupted between the resolvase-encoding gene res and s044 by complex integrons conferring MDR (Boyd et al., 2008). Interestingly, a similar variable region is inserted in s023 in the SGI1-variant SGI2 (formerly SGI1-J; Levings et al., 2008).

Currently, the genetic determinants and the nature of the interactions allowing the specific mobilization of SGI1 by ACPs remain largely unknown. Recent work revealed that the transcriptional activator AcaCD encoded by ACPs triggers the excision of SGI1 (Carraro et al., 2014a). Indeed, AcaCD-binding motifs were identified in the promoter region of the recombination directionality factor-encoding gene xis as well as upstream of putative regulatory and conjugation proteins (Figure 3C). SGI1 was reported to be highly stable, even after 350 generations without selective pressure (Kiss et al., 2012). Nevertheless, these assays were carried out in cells lacking an ACP. This is a major bias since SGI1 cannot excise in the absence of AcaCD (Carraro et al., 2014a). Interspecies mobilization of SGI1 between S. enterica and E. coli was reported to be highly variable (10–5 to 10–2 transconjugants per donor cell after overnight matings), depending on the Salmonella strain, the SGI1 variant and the IncA/C helper plasmid (Doublet et al., 2005; Kiss et al., 2012). In contrast, the frequency of transfer of SGI1 mobilized by pVCR94ΔX between E. coli strains was so high that virtually all recipient cells harbored SGI1 after mating (Carraro et al., 2014a).

MGIVmi1-like Elements

ACPs also trans-mobilize MGIVmi1, a 16.5 kb element that belongs to a family of MGIs unrelated to SGI1 and to the MGIs mobilized by SRIs (Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a). AcaCD binding sites were detected upstream of 490 and xis (formally 420), which code respectively for a 195-amino acids MobI-like protein and a 94-amino acid residue putative recombination directionality factor (Figure 3C). Similar characteristics are found in several GIs inserted in Vibrio mimicus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Shewanella putrefaciens genomes (Carraro et al., 2015a). Although these GIs are highly variable in size and content, their conserved key features strongly suggest that they are mobilizable by ACPs. Excision of MGIVmi1 was found to be AcaCD-dependent and its transfer requires the conjugative machinery encoded by ACPs. Here again, the exact mechanism remains unknown and further investigation is needed. However, based on the homology with the structure of the mob1 mobilization module of SRIs and ACPs, we hypothesized that the oriT locus of these GIs lies within the large intergenic region located upstream of the AcaCD-dependent gene coding for a MobI homolog (Carraro et al., 2015a).

Diversity of FlhCD-like Transcriptional Activators Amongst Conjugative Elements

A search for additional FlhCD-like regulators amongst other mobile genetic elements was carried out. Because homologies between SetCD and AcaCD, and the master flagellar activator FlhCD, are very weak, the Pfam HMM profiles for FlhC (PF05280) and FlhD (PF05247) domains are unsuitable to find functional orthologs of SetC/AcaC-like and SetD/AcaD-like activators in bacterial genomes. To solve this problem, we generated new HMM profiles based on alignments of the primary sequence of SetC/AcaC and SetD/AcaD protein orthologs. Screening of the Genbank non-redundant protein sequence database using these new profiles revealed a large number of homologous proteins encoded by diverse types of mobile genetic elements in Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae. Phylogenetic reconstructions using a representative subset of SetC/AcaC and SetD/AcaD orthologs revealed identical clustering in three distinct families distantly related to FlhC and FlhD: (i) SetC and SetD encoded by SRIs, (ii) AcaC and AcaD encoded by ACPs, (iii) putative proteins encoded by SGI1-like elements, S006 and S007, here renamed SgaC and SgaD (SGI1 activator subunits C and D), (iv) putative proteins encoded by pAQU1-like conjugative plasmids, 208 and 209 that we named AqaD and AqaC (pAQU1 activator subunits C and D), (v) putative proteins encoded by pAsa4, G057 and G056, here renamed AsaC and AsaD (pAsa4 activator subunits C and D; Figure 4). Interestingly, the genes coding for these putative transcriptional regulators are found in a similar genetic context in all cases (Figure 5). They are found in close proximity to a gene coding for a TraG homolog, a component of the conjugative apparatus, a gene coding for putative lysozyme-like protein. and genes coding for homologs of the SrpRM partition system and MobI protein. Further investigation are needed to confirm the functionality of these putative activator complexes regarding the activation of their cognate mobile GIs, and their potential impact on other genetic elements.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic trees based on alignments of amino acid sequences of SetC/AcaC (A) and SetD/AcaD (B) orthologs. The flagellar transcriptional activator proteins FlhC and FlhD of E. coli (Ec) and Serratia marcescens (Sm) were used as outgroups in phylogenetic analyses. Bootstrap values are indicated when over 80%. The individual scale bars represent genetic distances.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of the genetic context of genes coding for SetCD/AcaCD orthologs in diverse mobile genetic elements. Schematic representation of demonstrated or putative regulatory regions of SXT from V. cholerae O139 (AY055428.1), pVCR94 from V. cholerae O1 El Tor (NC_023291), pAQU1 from P. damselae subsp. damselae (NC_016983.1), pAsa4 from Aeromonas salmonicida (CP000645.1) and Salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI1) from S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 (AF261825.2). Arrows of similar color represent genes predicted to have similar functions and are color-coded as in Figure 1 legend. Circles indicate the position of origins of transfer (pale blue, oriT), of the origin of replication (black, oriV) of pVCR94 based on identity with pRA1, and the position of the attP site for chromosomal integration of SXT by site-specific recombination (orange).

Concluding Remarks and Perspectives

In the current context of rapid emergence and spread of MDR, it has become essential to get a better understanding of the dynamics and the mechanisms of transfer and regulation of mobile GIs that promote such resistance. A plethora of studies have been aimed at characterizing the determinants of transfer of various model conjugative genetic elements such as ICEBs1, Tn916, CTnDOT, R388, pESBL, pSL20, R27 (Celli and Trieu-Cuot, 1998; Marra and Scott, 1999; Auchtung et al., 2005; Gibert et al., 2013; Waters and Salyers, 2013; Fernandez-Lopez et al., 2014; Yamaichi et al., 2015). Extensive research on SRIs and recent work on ACPs have refined our grasp of the biology and regulation of these major players of MDR propagation. Classical genetics and modern molecular methods have facilitated the complete characterization of the regulons of SetCD and AcaCD, which greatly improved our understanding of SRIs, ACPs, and the elements they mobilize.

Mobilization of GIs requires the SetCD- or AcaCD-dependent activation of their excision, and involves three distinct mechanisms of oriT recognition and DNA processing. First, the MGI-SRI model is based on the recognition of a MGI-borne sequence mimicking the oriT of the self-transmissible SRI. This oriT counterfeit is likely recognized as a genuine oriT by the relaxosome of SRIs, thereby leading to MGI transfer through the SRI-encoded mating pore. Second, the MGIVmi1-ACP model likely relies on oriT recognition of MGI by its cognate MobI-like protein (MobIMGI), whose expression depends on AcaCD. The subsequent DNA processing at oriT of the MGI likely results from the interaction of MobIMGI with the MobIA/C-less relaxosome encoded by ACPs. Finally, the SGI1-ACP model remains the most elusive mechanism of mobilization as no oriTIncA/C sequence or MobI-like encoding gene has been identified so far in the sequence of SGI1-like elements. Further experiments are ongoing to precisely determine the mechanisms leading to the mobiliation of such GIs, and potentially of newly identified GIs.

Exploitation of experimentally determined SetCD and AcaCD recognition motifs to use them as specific tags for in silico analyses of bacterial genomes is a powerful approach to identify new mobile GIs mobilized by either SRIs or ACPs (Carraro et al., 2014a, 2015a). Moreover, additional FlhCD-like regulators were identified, which given their degree of divergence with AcaCD and SetCD, likely recognized unrelated DNA motifs. We anticipate that characterization of these motifs will facilitate the discovery of additional families of MGIs in sequenced bacterial genomes.

Mobile genetic elements and their bacterial host are inherently connected. Horizontally acquired DNA is often silenced by bacterial host factors such as H-NS-like proteins, most likely to limit the impact of exogenous DNA on endogenous regulatory networks and metabolic pathways (Dorman, 2004, 2014; Navarre et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2014). In the case of SRIs, IHF was shown to be mandatory for V. cholerae to act as a donor of SXT, but dispensable in E. coli donors (McLeod et al., 2006). The host factor Fis does not influence SXT transfer to or from V. cholerae. Further studies will be required to evaluate the influence of host factors on the dynamics of ACPs. Reciprocally, SRIs and ACPs, could interfere with the regulation of the host cell cellular processes. Besides the targets identified in MGIs, no clear interactions of SetCD and AcaCD with chromosomal loci in E. coli were detected (Carraro et al., 2014a; Poulin-Laprade et al., 2015). Nevertheless, considering the limitations of experimental settings and the broad host range of SRIs and ACPs, interactions with host metabolic pathways or other bacterial responses cannot be excluded. SetCD and AcaCD could also target plasmids of other incompatibility groups or other mobile GIs. Finally, other conjugative elements that code for FlhCD-like regulators could have a significant impact on their host biology.

Further investigations on the regulation of self-transmissible and mobilizable genetic elements will ultimately unravel the interconnections and the mechanism by which MDR and other adaptive traits spread among bacterial populations. In the war against the rampant emergence of untreatable pathogenic bacteria, fundamental knowledge regarding the key determinants at play for the dissemination of MDR will be an undeniable asset. To prevent a possible and imminent post-antibiotic era, mankind could find its salvation in the development of a new generation of molecules targeting key regulators aimed at confining or halting the exchange of MDR-conferring mobile genetic elements in patients, or even cure them from bacterial populations.

Authors’ Note

After acceptance of this review, our results demonstrating the involvement of AcaCD in the excision of SGI1 (Carraro et al., 2014a) were confirmed by Kiss et al. (2015). This paper also explores the role of SgaCD (Figures 4 and 5 of this review) and strongly suggests that similarly to its IncA/C-encoded counterpart AcaCD, SgaCD of SGI1 activates the promoter of xis and the subsequent excision of this genomic island.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to A. Lavigueur for critical reading of the manuscript. We are thankful to D. Matteau for its contribution to Figure 1. This work was supported by a Discovery Grant and Discovery Acceleration Supplement from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (326810 and 412288 to VB). VB holds a Canada Research Chair in molecular bacterial genetics. DPL was supported by a scholarship from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec–Nature et Technologies (FRQNT).

References

- Achard A., Leclercq R. (2007). Characterization of a small mobilizable transposon, MTnSag1, in Streptococcus agalactiae. J. Bacteriol. 189, 4328–4331. 10.1128/JB.00213-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armshaw P., Pembroke J. T. (2013). Control of expression of the ICE R391 encoded UV-inducible cell-sensitising function. BMC Microbiol. 13:195. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchtung J. M., Lee C. A., Monson R. E., Lehman A. P., Grossman A. D. (2005). Regulation of a Bacillus subtilis mobile genetic element by intercellular signaling and the global DNA damage response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12554–12559. 10.1073/pnas.0505835102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badhai J., Kumari P., Krishnan P., Ramamurthy T., Das S. K. (2013). Presence of SXT integrating conjugative element in marine bacteria isolated from the mucus of the coral Fungia echinata from Andaman Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 338, 118–123. 10.1111/1574-6968.12033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu Z., Bikard D., Mazel D. (2010). Conjugative DNA transfer induces the bacterial SOS response and promotes antibiotic resistance development through integron activation. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001165. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu Z., Krin E., Mazel D. (2012). Connecting environment and genome plasticity in the characterization of transformation-induced SOS regulation and carbon catabolite control of the Vibrio cholerae integron integrase. J. Bacteriol. 194, 1659–1667. 10.1128/JB.05982-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind A., Stemplinger I., Jungwirth R., Giamarellou H. (1996). Characterization of the plasmidic beta-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter J. C., Funnell B. E. (2014). Plasmid partition mechanisms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, 1–20. 10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0023-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaber J. W., Burrus V., Hochhut B., Waldor M. K. (2002a). Comparison of SXT and R391, two conjugative integrating elements: definition of a genetic backbone for the mobilization of resistance determinants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 2065–2070. 10.1007/s000180200006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaber J. W., Hochhut B., Waldor M. K. (2002b). Genomic and functional analyses of SXT, an integrating antibiotic resistance gene transfer element derived from Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 184, 4259–4269. 10.1128/JB.184.15.4259-4269.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaber J. W., Hochhut B., Waldor M. K. (2004). SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature 427, 72–74. 10.1038/nature02241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaber J. W., Waldor M. K. (2004). Identification of operators and promoters that control SXT conjugative transfer. J. Bacteriol. 186, 5945–5949. 10.1128/JB.186.17.5945-5949.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger X., Morel C., Gonot F., Puymege A., Decaris B., Guedon G. (2011). Site-specific accretion of an integrative conjugative element together with a related genomic island leads to cis mobilization and gene capture. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 912–925. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger X., Payot S., Leblond-Bourget N., Guedon G. (2014). Conjugative and mobilizable genomic islands in bacteria: evolution and diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 720–760. 10.1111/1574-6976.12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger X., Roberts A. P., Morel C., Choulet F., Pavlovic G., Mullany P., et al. (2009). Conjugative transfer of the integrative conjugative elements ICESt1 and ICESt3 from Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2764–2775. 10.1128/JB.01412-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D., Xu Z., Harrison E. M., Tai C., Wei Y., He X., et al. (2012). ICEberg: a web-based resource for integrative and conjugative elements found in Bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D621–D626. 10.1093/nar/gkr846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltner D., Macmahon C., Pembroke J. T., Strike P., Osborn A. M. (2002). R391: a conjugative integrating mosaic comprised of phage, plasmid, and transposon elements. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5158–5169. 10.1128/JB.184.18.5158-5169.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeleau E., Brouillette E., Robichaud N., Burrus V. (2010). Beyond antibiotic resistance: integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 family that encode novel diguanylate cyclases participate to c-di-GMP signalling in Vibrio cholerae. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 510–523. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D. A., Shi X., Hu Q. H., Ng L. K., Doublet B., Cloeckaert A., et al. (2008). Salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI1), variant SGI1-I, and new variant SGI1-O in Proteus mirabilis clinical and food isolates from China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 340–344. 10.1128/AAC.00902-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning D. F., Busby S. J. (2004). The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 57–65. 10.1038/nrmicro787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrus V., Marrero J., Waldor M. K. (2006). The current ICE age: biology and evolution of SXT-related integrating conjugative elements. Plasmid 55, 173–183. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrus V., Pavlovic G., Decaris B., Guedon G. (2002). Conjugative transposons: the tip of the iceberg. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 601–610. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrus V., Waldor M. K. (2003). Control of SXT integration and excision. J. Bacteriol. 185, 5045–5054. 10.1128/JB.185.17.5045-5054.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrus V., Waldor M. K. (2004). Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements. Res. Microbiol. 155, 376–386. 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call D. R., Singer R. S., Meng D., Broschat S. L., Orfe L. H., Anderson J. M., et al. (2010). blaCMY-2-positive IncA/C plasmids from Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica are a distinct component of a larger lineage of plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 590–596. 10.1128/AAC.00055-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambray G., Sanchez-Alberola N., Campoy S., Guerin E., Da Re S., Gonzalez-Zorn B., et al. (2011). Prevalence of SOS-mediated control of integron integrase expression as an adaptive trait of chromosomal and mobile integrons. Mob. DNA 2, 6. 10.1186/1759-8753-2-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A. (2013). Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 298–304. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Bertini A., Villa L., Falbo V., Hopkins K. L., Threlfall E. J. (2005). Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 63, 219–228. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Burrus V. (2014). Biology of Three ICE Families: SXT/R391, ICEBs1, and ICESt1/ICESt3. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, 1–20. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0008-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Libante V., Morel C., Decaris B., Charron-Bourgoin F., Leblond P., et al. (2011). Differential regulation of two closely related integrative and conjugative elements from Streptococcus thermophilus. BMC Microbiol. 11:238. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Matteau D., Burrus V., Rodrigue S. (2015a). Unraveling the regulatory network of IncA/C plasmid mobilization: when genomic islands hijack conjugative elements. Mob. Genet. Elements 5, 1–5. 10.1080/2159256x.2015.1045116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Poulin D., Burrus V. (2015b). Replication and active partition of integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) of the SXT/R391 family: the line between ICEs and conjugative plasmids is getting thinner. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005298. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Matteau D., Luo P., Rodrigue S., Burrus V. (2014a). The master activator of IncA/C conjugative plasmids stimulates genomic islands and multidrug resistance dissemination. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004714. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Sauve M., Matteau D., Lauzon G., Rodrigue S., Burrus V. (2014b). Development of pVCR94ΔX from Vibrio cholerae, a prototype for studying multidrug resistant IncA/C conjugative plasmids. Front. Microbiol. 5:44. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli D., Daccord A., Rene M., Burrus V. (2008). Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and a new gene required for mobilization of the SXT/R391 family of integrating conjugative elements. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5328–5338. 10.1128/JB.00150-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J., Trieu-Cuot P. (1998). Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol. Microbiol. 28, 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Yang H., Pavletich N. P. (2008). Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature 453, 489–484. 10.1038/nature06971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevance F. F., Hughes K. T. (2008). Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 455–465. 10.1038/nrmicro1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee J. N., Datta N., Hedges R. W. (1972). R factors from Proteus rettgeri. J. Gen. Microbiol. 72, 543–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daccord A., Ceccarelli D., Burrus V. (2010). Integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 family trigger the excision and drive the mobilization of a new class of Vibrio genomic islands. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 576–588. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daccord A., Ceccarelli D., Rodrigue S., Burrus V. (2013). Comparative analysis of mobilizable genomic islands. J. Bacteriol. 195, 606–614. 10.1128/JB.01985-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daccord A., Mursell M., Poulin-Laprade D., Burrus V. (2012). Dynamics of the SetCD-regulated integration and excision of genomic islands mobilized by integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 family. J. Bacteriol. 194, 5794–5802. 10.1128/JB.01093-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J., Davies D. (2010). Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 417–433. 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz F., Frost L. S., Meyer R. J., Zechner E. L. (2010). Conjugative DNA metabolism in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 18–40. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo C. S., Hikima J., Jang H. B., Nho S. W., Jung T. S., Wongtavatchai J., et al. (2013). Comparative sequence analysis of a multidrug-resistant plasmid from Aeromonas hydrophila. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 120–129. 10.1128/AAC.01239-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulou I. D., Russell J. E., Mohd-Zain Z., Herbert R., Crook D. W. (2002). Site-specific recombination with the chromosomal tRNA(Leu) gene by the large conjugative Haemophilus resistance plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1602–1603. 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1602-1603.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., Yang Y., Lu Q., Wang Y., Chen Y., Deng L., et al. (2008). The prevalence of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from five children’s hospitals in China. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27, 915–921. 10.1007/s10096-008-0532-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J. (2004). H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 391–400. 10.1038/nrmicro883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J. (2014). H-NS-like nucleoid-associated proteins, mobile genetic elements and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. Plasmid 75, 1–11. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douard G., Praud K., Cloeckaert A., Doublet B. (2010). The Salmonella genomic island 1 is specifically mobilized in trans by the IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid family. PLoS ONE 5:e15302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublet B., Boyd D., Mulvey M. R., Cloeckaert A. (2005). The Salmonella genomic island 1 is an integrative mobilizable element. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1911–1924. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziewit L., Jazurek M., Drewniak L., Baj J., Bartosik D. (2007). The SXT conjugative element and linear prophage N15 encode toxin-antitoxin-stabilizing systems homologous to the tad-ata module of the Paracoccus aminophilus plasmid pAMI2. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1983–1997. 10.1128/JB.01610-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero J., Loot C., Nivina A., Mazel D. (2014). The integron: adaptation on demand. Microbiol. Spectr. 3, 1–22. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0019-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Alarcon C., Singer R. S., Johnson T. J. (2011). Comparative genomics of multidrug resistance-encoding IncA/C plasmids from commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli from multiple animal sources. PLoS ONE 6:e23415. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez R., Del Campo I., Revilla C., Cuevas A., De La Cruz F. (2014). Negative feedback and transcriptional overshooting in a regulatory network for horizontal gene transfer. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004171. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald D. M., Bonocora R. P., Wade J. T. (2014). Comprehensive mapping of the Escherichia coli flagellar regulatory network. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004649. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folster J. P., Pecic G., Mccullough A., Rickert R., Whichard J. M. (2011). Characterization of bla(CMY)-encoding plasmids among Salmonella isolated in the United States in 2007. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8, 1289–1294. 10.1089/fpd.2011.0944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folster J. P., Pecic G., Singh A., Duval B., Rickert R., Ayers S., et al. (2012). Characterization of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolated from food animals, retail meat, and humans in the United States 2009. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9, 638–645. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke W. F., Welch T. J., Mcdermott P. F., Mammel M. K., Leclerc J. E., White D. G., et al. (2009). Comparative genomics of the IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid family. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4750–4757. 10.1128/JB.00189-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimand M., Guiyoule A., Gerbaud G., Rasoamanana B., Chanteau S., Carniel E., et al. (1997). Multidrug resistance in Yersinia pestis mediated by a transferable plasmid. N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 677–680. 10.1056/NEJM199709043371004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriss G., Burrus V. (2013). “Integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 Family,” in Bacterial Integrative Mobile Genetic Elements, eds Roberts A. P., Mullany P. (Austin, TX: Landes Biosciences; ), 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Garriss G., Poulin-Laprade D., Burrus V. (2013). DNA-damaging agents induce the RecA-independent homologous recombination functions of integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 family. J. Bacteriol. 195, 1991–2003. 10.1128/JB.02090-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriss G., Waldor M. K., Burrus V. (2009). Mobile antibiotic resistance encoding elements promote their own diversity. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000775. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibert M., Juarez A., Madrid C., Balsalobre C. (2013). New insights in the role of HtdA in the regulation of R27 conjugation. Plasmid 70, 61–68. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles W. P., Benson A. K., Olson M. E., Hutkins R. W., Whichard J. M., Winokur P. L., et al. (2004). DNA sequence analysis of regions surrounding blaCMY-2 from multiple Salmonella plasmid backbones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 2845–2852. 10.1128/AAC.48.8.2845-2852.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble F. S., Sauer R. T. (1985). Mutations in bacteriophage lambda repressor that prevent RecA-mediated cleavage. J. Bacteriol. 162, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girlich D., Dortet L., Poirel L., Nordmann P. (2015). Integration of the blaNDM–1 carbapenemase gene into Proteus genomic island 1 (PGI1-PmPEL) in a Proteus mirabilis clinical isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 98–102. 10.1093/jac/dku371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn L. M., Lindsey R. L., Frank J. F., Meinersmann R. J., Englen M. D., Fedorka-Cray P. J., et al. (2011). Analysis of antimicrobial resistance genes detected in multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolated from food animals. Microb. Drug Resist. 17, 407–418. 10.1089/mdr.2010.0189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgani N., Ahlbrand S., Patterson A., Pourmand N. (2009). Detection of point mutations associated with antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34, 414–418. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann E. (2010). Autonomous plasmid-like replication of Bacillus ICEBs1: a general feature of integrative conjugative elements? Mol. Microbiol. 75, 261–263. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin E., Cambray G., Sanchez-Alberola N., Campoy S., Erill I., Da Re S., et al. (2009). The SOS response controls integron recombination. Science 324, 1034. 10.1126/science.1172914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmini J., Quintais L., Garcillan-Barcia M. P., De La Cruz F., Rocha E. P. (2011). The repertoire of ICE in prokaryotes underscores the unity, diversity, and ubiquity of conjugation. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002222. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. F., Zhang W. H., Ren S. Q., Yang L., Lu D. H., Zeng Z. L., et al. (2014). IncA/C plasmid-mediated spread of CMY-2 in multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from food animals in China. PLoS ONE 9:e96738. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft R. J., Mittler J. E., Traxler B. (2009). Competition favours reduced cost of plasmids to host bacteria. ISME J. 3, 761–769. 10.1038/ismej.2009.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. M. (2010). Salmonella genomic islands and antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica. Future Microbiol. 5, 1525–1538. 10.2217/fmb.10.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada S., Ishii Y., Saga T., Tateda K., Yamaguchi K. (2010). Chromosomally encoded blaCMY-2 located on a novel SXT/R391-related integrating conjugative element in a Proteus mirabilis clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3545–3550. 10.1128/AAC.00111-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Kudo Y., Kumagai S. (2014). Impact of seafood regulations for Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection and verification by analyses of seafood contamination and infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 142, 2237–2247. 10.1017/S0950268814001897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C. J., Hall R. M. (2014). pRMH760, a precursor of A/C(2) plasmids carrying blaCMY and blaNDM genes. Microb. Drug Resist. 20, 416–423. 10.1089/mdr.2014.0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C. J., Hall R. M. (2015). The A to Z of A/C plasmids. Plasmid [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley D. K., McClure W. R. (1983). Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 2237–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhut B., Lotfi Y., Mazel D., Faruque S. M., Woodgate R., Waldor M. K. (2001). Molecular analysis of antibiotic resistance gene clusters in Vibrio cholerae O139 and O1 SXT constins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2991–3000. 10.1128/AAC.45.11.2991-3000.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]