Abstract

We measured cell-associated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 DNA (CAD) and RNA (CAR) and plasma HIV-1 RNA in blood samples from 20 children in the Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral (CHER) cohort after 7–8 years of suppressive combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Children who initiated cART early (<2 months; n = 12) had lower HIV-1 CAD (median, 48 vs 216; P < .01) and CAR (median, 5 vs 436; P < .01) per million peripheral blood mononuclear cells than children who started later (≥2 months; n = 8). Plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were not significantly lower in early-treated children (0.5 vs 1.2 copies/mL; P = .16). Early treatment at <2 months of age reduces the number of HIV-infected cells and HIV CAR.

Keywords: early infant antiretroviral therapy, HIV-1 cell-associated DNA, HIV-1 cell associated RNA, HIV-1 single copy assay, measures of HIV-1 persistence, transcriptionally active proviruses

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) initiated during chronic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection suppresses viremia but does not eliminate long-lived cells that were infected before cART was started. Recent evidence suggests that the persistence of HIV-1–infected cells may be related, in part, to HIV-1 integrations into growth regulatory genes that enhance the proliferation and survival of infected cells, resulting in expanded clones [1]. HIV-1 could possibly persist through ongoing replication, although the absence of viral evolution in most patients suggests that this plays a limited role [2]. Viral rebound in the “Mississippi baby” after 2 years of undetectable viral replication [3] suggests that viral eradication through early cART is not likely. Although HIV cell-associated DNA (CAD) decay plateaus after 4 years in adults, a recent report of 4 youth, who initiated cART in early infancy, provided evidence of continued CAD decay [4]. Such studies are limited by small sample sizes, subtype B virus, and quantification of HIV-1 DNA only and not other measures of HIV-1 persistence, such as cell-associated HIV-1 RNA (CAR) and persistent plasma viremia.

The Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral (CHER) study established that early time-limited cART (either for 40 or 96 weeks) initiated around a median of 7 weeks of life improved the primary outcome (a composite of virologic and immunologic outcomes and survival) compared to initiation, around a median of 21 weeks, of continuous cART, based on clinical or immunological grounds [5]. Nevertheless, some children initially randomized to early time-limited cART did not interrupt cART. Either the children had already met clinical or immunological criteria for continuous cART or were in a parallel group (Part B) with a baseline CD4 lymphocyte count <25% that remained on continuous cART. Consequently, children who initiated continuous cART over an age range were available for study. The objective of the current study was to assess several measures of HIV-1 persistence (CAD, CAR, and plasma HIV-1 RNA) after 7–8 years of continuous cART comparing children who initiated ART early (<2 months) versus later (≥2 months).

METHODS

Patients

Twenty children were recruited from the post-CHER cohort, during October to November 2013, based on being on continuous cART and not having viral loads >400 copies in the most recent 3 years. Twelve children started cART at <2 months of age and 8 children ≥2 months of age.

Children were 7–8 years of age at the time of the investigation: 15 to 20 mL of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid blood was drawn as a minimal risk procedure. Stored peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) and plasma samples collected during CHER, either prior to cART initiation or early after initiation (when pre-ART specimens were not available), were collected to confirm that the patient's viral quasi-species were efficiently amplified with the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) primers and probes used. Parents or legal guardians provided consent for participation in the study. The study was approved by the Human Research Committee of the University of Stellenbosch (N13/04/046). Testing of samples was performed at the University of Pittsburgh under IRB exemption PRO13070189.

Laboratory Methods

Plasma HIV-1 RNA monitoring was initially done with the Roche Amplicor HIV Monitor assay version 1.0 (lower limit of detection [LOD] of 400 copies/mL), then with the Roche Amplicor HIV Monitor assay ultrasensitive protocol (LOD of 50 copies/mL). After completion of the CHER study in August 2011, the Abbott Diagnostics RealTime HIV-1 assay was used (LOD of 150 copies/mL for 200 microliter input or 40 copies/mL for 1 mL input).

PBMCs were separated according to the HANC Cross-Network PBMC processing SOP (https://www.hanc.info/labs/labresources/procedures/Pages/pbmcSop.aspx) and stored in aliquots of 2.5 million cells in liquid nitrogen.

qPCR Assays

PBMCs aliquots and plasma were extracted and were quantified with ultrasensitive real-time PCR assays on a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics) using previously described assays for CAD [6], CAR [7], and single-copy RNA in plasma [8]. CAD and CAR results were normalized for cell number by quantification of the CCR5 gene. For the CAR assay, all extracts were DNAse treated; and to exclude residual HIV DNA, all samples were tested in parallel in qPCR reactions lacking reverse transcriptase. IPO8 mRNA was quantified to control for CAR extraction and reverse transcription.

Statistics

Statistics and data analyses were done using R3.1.0 [9]. For categorical comparisons, Fisher exact test was used, and for comparison of continuous variables between groups, Mann–Whitney U test was used.

RESULTS

Patients

Age range was 7.0–8.3 (median, 7.3; interquartile range [IQR], 7.1–7.9) years old at the time of the investigation. Patients were categorized according to the age of therapy initiation: early (<2 months) or late (≥2 months of age); 12 children initiated therapy early (median, 53; range, 44–57 days after birth) and 8 children later (median, 170; range, 61–450 days after birth). Table 1 shows comparisons of age, treatment, and laboratory parameters at the cART initiation (baseline or early therapy) and last follow-up time-points (7–8 years on therapy). There were no significant differences at baseline between the early- and later-treated children (Table 1). Patients received zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC), and lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) (n = 17); abacavir (ABC), 3TC, and LPV/r (n = 2); and AZT, 3TC, and efavirenz (n = 1), respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Children Studied

| Variable | Therapy Start Category (median, IQR) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Time-Point: | Early <2 mo (n = 12) | Late ≥2 mo (n = 8) | |

| Days of life when cART initiated | 51.8 (50–54) | 170 (73.5–278.8) | <.001 |

| CD4 nadir (%) | 20.8 (14.6–24.9) | 17.3 (13.0–21.5) | .59 |

| Baseline log10 plasma HIV-1 RNA | 5.8 (5.6–5.9) | 5.9 (5.9–5.9) | .25 |

| Late/7–8 y time-point: | |||

| Age (months) | 87.5 (86.0–90.8) | 92.2 (87.6–97.6) | .35 |

| Estimated time to suppression | 143.5 (86.6–266.0) | 406.8 (84–608.4) | .76 |

| Time treated (months) | 86.0 (84.0–88.8) | 86.0 (82.0–91.8) | .64 |

| Time suppressed (months) | 74.5 (67.3–83.3) | 69.0 (63.0–74.8) | .37 |

| CD4 (%) | 37.6 (34.3–38.4) | 36.26 (31.3–39.4) | .85 |

Patients were categorized according to being initiated early (<2 months) or late (≥2 months). Statistical comparisons: P values were by Mann–Whitney U tests. Time suppressed is defined as the continuous period with viral load <400 copies/mL, because different HIV RNA testing platforms with lower limits of detection (40–400 copies/mL) were used over the observation period.

Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range.

HIV-1 Cell-Associated DNA (CAD), HIV-1 Cell-Associated RNA (CAR), and HIV-1 Plasma RNA

Therapy Initiation Time-Point

At the therapy initiation time-point (baseline or early after therapy initiation, median, 1 month; range, 0–6 months after therapy initiation) median (IQR) HIV-1 CAD was: 1571 (177.9–3,931.5) per million PBMCs in early-treated children and 6155 (3,990.2–8,649.0) per million PBMCs in later-treated children (P = .04); median HIV-1 plasma RNA (IQR) was: 5364 (251.2–3,305,613.7) copies/mL in early and 1 537 052 (99,861.7–3,605,184.3) copies/mL in later-treated children (P = .17).

Current (7–8-Year-Old) Time-Point

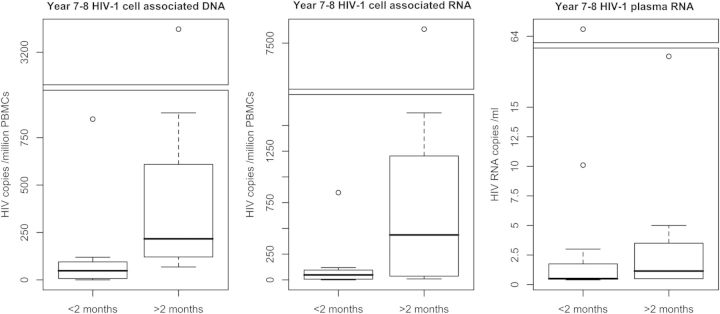

HIV-1 CAD was significantly lower (P < .01) in children who initiated early cART compared to late median (IQR): 48 (10–94.0) compared to 216 (135–473) copies/million PBMCs (Figure 1). Of 12 children who started early, 1 had undetectable CAD (in a total of 2.5 million cells assayed), versus none of 8 who started late; and another 2 children who initiated cART early had HIV-1 DNA levels less than 2 copies/million PBMCs compared to none of the 8 children initiated later on cART.

Figure 1.

Boxplots of HIV-1 cell-associated DNA and RNA and plasma RNA in patients at 7–8 years of age who were respectively initiated on therapy before or after 2 months of age. Patients who started cART before 2 months had significantly lower cell-associated HIV-1 DNA and RNA (P < .01, Mann–Whitney U test). To show data spread and fit in outliers, gapped boxplots (discontinuous y axes) were used. Gap ranges contained no patient results. The first figure has a gap between 1000 and 3000 HIV-1 DNA copies/million PBMCs, the second between 1800 and 7000 HIV-1 RNA copies/million PBMCs, and the third between 20 and 63 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL. Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

HIV-1 CAR was also significantly lower (P < .01) in children who started early versus late: median (IQR): 5 (4–37) versus 436 (48–994) copies/million PBMCs (Figure 1). Seven of 12 (58%) patients starting therapy before 2 months had undetectable CAR (lower limit of detection is dependent on cell input and was <5 or less, for all but 1 patient, in which it was <9 copies/million PBMCs) compared to only 1/8 (12.5%) starting after 2 months (P = .07).

Median (IQR) HIV-1 plasma RNA was 0.5 (0.5–1.1) in patients who started cART before 2 months of age versus 1.2 (0.5–2.8) copies/mL in patients who started after 2 months (P = .16) (Figure 1); 9 of 12 patients (75%) starting cART before 2 months had undetectable HIV-1 plasma RNA versus 3 of 8 (37.5%) who started later (P = .17).

Because viral load monitoring was not routinely and frequently performed, the time to suppression was interpolated from between the last detectable and the first suppressed viral load (<400 copies/mL). There was no significant difference in time to virologic suppression for patients starting before or after 2 months of age: median (IQR) 143.5 (86.6–266.0) (range, 83.5–848.0) days versus: median (IQR): 406.8 (84–608.4) (P =.76) (range, 81.0–773.0) days.

Individual patient results are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

This is the first investigation showing that early cART in infancy (<2 months of age) administered continuously for 7–8 years reduces both the number of HIV-infected cells and the HIV-1 transcriptional activity of infected cells in blood (P < .01; Mann–Whitney U) compared with children treated ≥2 months of age. One early-treated infant had undetectable HIV-1 CAD in 2.5 million PBMCs. Seven out of 12 early treated infants versus 1 out of 8 late-treated infants had undetectable HIV-1 CAR.

Our findings corroborate previous reports showing that early treatment of infants is associated with lower CAD and also extends the observation to CAR [4, 10]. In a Canadian report of 4 children who initiated therapy within 72 hours of birth, CAD became undetectable despite detectable CAR. It was not indicated in this report whether the assay for CAR included a reverse transcription negative control to exclude HIV-1 DNA contamination as the source of detectable CAR [11], whereas in our study, extracted nucleic acid was DNAse treated and residual HIV-1 DNA excluded by no–reverse transcriptase controls.

Eradication of HIV with cART alone may not be possible given that the Mississippi child rebounded 27 months after cART was interrupted [3]. This case suggests that even when therapy is initiated within 30 hours of birth, in human infants, it may not prevent reservoir establishment. Further evidence comes from experimental rectal infection of adult rhesus monkeys that all had viral rebound, although delayed, despite cART being initiated within 72 hours of infection [12]. However, even if eradication through early therapy is not feasible, there are 2 remaining benefits: (1) it improves prognosis and thereby prevent early deaths; and (2) it may be an important component when combined with adjunctive immunotherapy in achieving prolonged cART-free remission of HIV. Post-therapy control after cART alone has not yet been reported in children as it has in adults [13]. Nevertheless, the CHER study suggests that there is at least some immunologic benefit of early cART, as children who received early therapy followed by cART interruption paradoxically spent less total time on cART (initiated based on immunologic or clinical criteria) than patients from the deferred cART arm [5]. The time window to achieve benefit with early therapy in infants is not known. Our investigation suggests that therapy in the first 2 months of life could increase the chance of achieving very low levels of persisting CAD and CAR.

Our study has limitations. Patients were diagnosed between 28 to 71 days after birth. Only 1 patient was breastfed. It was therefore not possible to asses the effect of the timing of infection and route of transmission on measures of HIV persistence. The sensitivity of the assays are determined by the number of cells or volume of plasma assayed, and because the number and size of specimens were limited (collected as a minimal risk procedure), the inability to detect HIV-1 DNA or CAR does not indicate its absence: in the 1 patient with undetectable HIV-1 DNA, 2.5 million cells were assayed, but in the 8 patients with undetectable RNA, a median of only 301 275 cells (range, 112 950–623 250) were assayed. The CAD and CAR, moreover, do not discriminate intact sequences from sequences that are defective due to insertions or deletions or A-to-G hypermutations [14]. Because of limited sample, we could not determine whether transcriptional activity resulted in protein expression or maintenance of antibody or cellular immune responses. We were unable to fully assess the correlation of baseline CAD or CAR with on-treatment DNA/RNA because we lacked pre-cART samples on all patients. Pre-cART samples were available for 9 patients only; the first available stored specimens after cART initiation was at 1 month (n = 6), 3 months (n = 4), or 6 months (n = 1) for the remainder. The sample size of 20 patients provided limited power to detect differences in plasma HIV-1 RNA; however, the results suggest lower plasma HIV RNA in the early treated group.

The mechanism of benefit of early therapy is poorly understood and requires further investigation but is probably a combination of immune function preservation and reduction in the number of HIV-infected long-lived cells. Our investigation agrees with others that therapy reduces the quantity of HIV-1–infected cells [4, 11] and in addition shows a reduction in transcriptional activity of HIV-1–infected cells compared to later cART, an effect that was evident many years after cART initiation. If early therapy preserves an initial homotypic viral population prior to diversification and immune escape, it may provide a better opportunity for novel immunotherapeutic approaches. These include T-cell therapies or broadly neutralizing antibodies, which could achieve long-term viral control after cART discontinuation [15]. Early cART initiation in children therefore does not only hold immediate prognostic benefit but could potentially enhance response to future curative strategies.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Thank you to Jim Lemon, School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, author of the R plotrix package with assistance with the “gap.boxplot” function. We thank Avy Violari (Perinatal HIV Research Unit), Diana M. Gibb, and Abdel G. Babiker (University College of London) and Patrick Jean-Phillipe (Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine Inc) from the CHER steering committee, and Wendy Snowdon, GlaxoSmithKline, UK, for supporting the CHER study and for reviewing the manuscript. We thank Kennedy Otwombe (Perinatal HIV Research Unit) for assistance with CHER data retrieval, and Wendy Stevens, Contract Laboratory Services and University of the Witwatersrand, for specimen storage during the CHER study.

Financial support. This work was supported by The University of Pittsburgh Center for Global Health and Oppenheimer Memorial Trust. The CHER trial, including M. F. C., was supported through the Comprehensive International Program for Research in AIDS (CIPRA-SA: U19 AI53217R21). B. L. was supported through R01 HD071664, and grants from the SA MRC and Stellenbosch University Harry Crossley Foundation. The post-CHER cohort was funded by R01 HD071664.

Potential conflicts of interest. G. v. Z. reports grants from Oppenheimer Memorial Trust (for Sabbatical Support), grants from University of Pittsburgh Center for Global Health (for Sabbatical Support) and National Research Foundation (South Africa), during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Abbvie (honoraria for lecture material), outside the submitted work. B. L. reports grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grants from South Africa Medical Research Council, grants from Harry Crossley foundation, during the conduct of the study. M. F. C. reports grants from NIH during the conduct of the study. J. W. M. reports grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences, and share options from RFS Phamaceuticals, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, et al. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science 2014; 345:179–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearney MF, Spindler J, Shao W, et al. Lack of detectable HIV-1 molecular evolution during suppressive antiretroviral therapy. PLOS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stover K, Bock R, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “Mississippi Baby” now has detectable HIV, researchers find. NIH News; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luzuriaga K, Tabak B, Garber M, et al. Reduced HIV reservoirs after early treatment HIV-1 proviral reservoirs decay continously under sustained virologic control in early-treated HIV-1–infected children. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotton MF, Violari A, Otwombe K, et al. Early time-limited antiretroviral therapy versus deferred therapy in South African infants infected with HIV: results from the children with HIV early antiretroviral (CHER) randomised trial. Lancet 2013; 382:1555–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cillo AR, Krishnan A, Mitsuyasu RT, et al. Plasma viremia and cellular HIV-1 DNA persist despite autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for HIV-related lymphoma. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63:438–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cillo AR, Sobolewski MD, Bosch RJ, et al. Quantification of HIV-1 latency reversal in resting CD4+ T cells from patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:7078–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cillo AR, Vagratian D, Bedison M, et al. Improved single copy assays for quantification of persistent HIV-1 viremia in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:3944–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2014.

- 10.Ananworanich J, Puthanakit T, Suntarattiwong P, et al. Reduced markers of HIV persistence and restricted HIV-specific immune responses after early antiretroviral therapy in children. AIDS 2014; 28:1015–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bitnun A, Samson L, Chun T-W, et al. Early initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected newborn infants can achieve sustained virologic suppression with low frequency of CD4+ T-cells carrying HIV in peripheral blood. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1012–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitney JB, Hill AL, Sanisetty S, et al. Rapid seeding of the viral reservoir prior to SIV viraemia in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2014; 512:74–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sáez-Cirión A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLOS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho Y-C, Shan L, Hosmane NN, et al. Replication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure. Cell 2013; 155:540–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barouch DH, Whitney JB, Moldt B, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature 2013; 503:224–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.