Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

The purpose of this study was to describe prevalence of technology use among adults ages 65 and older, particularly for those with disability and activity-limiting symptoms and impairments.

Design and Methods:

Data from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study, a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries (N = 7,609), were analyzed. Analysis consisted of technology use (use of e-mail/text messages and the internet) by sociodemographic and health characteristics and prevalence ratios for technology usage by disability status.

Results:

Forty percent of older adults used e-mail or text messaging and 42.7% used the internet. Higher prevalence of technology use was associated with younger age, male sex, white race, higher education level, and being married (all p values <.001). After adjustment for sociodemographic and health characteristics, technology use decreased significantly with greater limitations in physical capacity and greater disability. Vision impairment and memory limitations were also associated with lower likelihood of technology use.

Implications:

Technology usage in U.S. older adults varied significantly by sociodemographic and health status. Prevalence of technology use differed by the type of disability and activity-limiting impairments. The internet, e-mail, and text messaging might be viable mediums for health promotion and communication, particularly for younger cohorts of older adults and those with certain types of impairment and less severe disability.

Key words: Internet, Impairment, E-mail, Text messaging, Health status

Advancements in communication technologies through the internet and mobile phones are recognized for their potential high impact and broad reach in health education, health monitoring, and support of health behaviors worldwide (World Health Organization, 2011). A notable aspect of mobile phones, in particular, is that older adults and marginalized segments of the population have better access and uptake of mobile technology compared with previous technologies (Gerber, Olazabal, Brown, & Pablos-Mendez, 2010). Recent data estimate that 79% of all Americans have computer access and 85% have a cell phone (Fox & Duggan, 2012; Internet World Statistics, 2012). The Pew Internet Project, which tracks internet use in the United States, reports steadily increasing numbers of older adults using the internet, with more than 50% reportedly going online in 2012 (Zickuhr & Madden, 2012). As reported by the U.S. Department of Commerce (2011), using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey School Enrollment and Internet Use Supplement of 2010, 41.6% of adults 65 years and older reported using the internet and 61.0% reported some type of computer use. A key benefit of technology is the opportunity to reach and engage older adults, including those at risk of isolation or reduced access to health care.

In 2010, 37% of older persons in the United States reported some type of physical or cognitive disability (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Given the predicted growth of the older adult population, from the current 13%–19% in 2030, the number of older adults living with disability will also increase (Christensen, Doblhammer, Rau, & Vaupel, 2009). Disability in older adults has been associated with increased risk for adverse health outcomes such as functional decline, recurrent hospitalizations, social isolation, and higher health care needs and costs (Giuliani et al., 2008; Guralnik, Fried, Simonsick, Kasper, & Lafferty, 1995; Nosek, Hughes, Swedlund, Taylor, & Swank, 2003). Preliminary evidence shows potential for improvements in health outcomes and social isolation for older adults through internet (ehealth) and mobile phone (mhealth) interventions (Cotten, Anderson, & McCullough, 2013; Lim et al., 2011; Nimrod, 2009; Scherr et al., 2009). However, wider application and dissemination of such interventions are dependent on older adults’ access to and use of these technologies.

Early studies on technology use in older adults showed lower rates of computer and internet use compared with other age groups. In a study of adults in the United Kingdom ages 60 and older, Selwyn, Gorard, Furlong, and Madden (2003) found computer use to vary substantially by demographic characteristics, with greater use associated with male sex, younger age, being married, and higher education level. Subsequent studies in the United States, Israel, and Australia show similar findings of computer use among older adults (Carpenter & Buday, 2007; Boulton-Lewis, Buys, Lovie-Kitchin, Barnett, & David, 2007; Heart & Kalderon, 2011). A consistent finding across multiple studies of computer or internet use in older adults is the role of perceived relevance to daily life. Both cross-sectional and intervention studies report the adoption and use of technology among older adults depends on perceived need, interest, and relevance (Carpenter & Buday, 2007; Selwyn et al., 2003; Sourbati, 2009). Other studies have tied lower rates of technology use to design and interface issues (Czaja & Lee, 2007), lack of training and support (Heart & Kalderon, 2011), and cost in relation to income (Wright & Hill, 2009). Through a web survey, Beach and colleagues (2009) explored acceptability of sharing personal information (e.g., toileting, taking medications, home mobility, cognition, driving behavior, and vital signs) through technological means among older adults and among adults with disabilities. The finding of significant variance by age and disability status for what was deemed acceptable indicates a need to balance potential for improved health with privacy considerations for use of technology in health and personal care.

To date, few studies have assessed internet use in more detail such as differentiating between communication, social networking, or information seeking. According to data from the Pew Research Center, among the 53% of adults ages 65 and older who go online, 86% use e-mail, 27% look online for information about health or medical issues, and 34% use social networking sites (Zickuhr & Madden, 2012). Using nationally representative data from the 2009U.S. National Health Interview Survey, Choi (2011) found 32.2% of adults ages 65–74 used the internet for health-related activities in the past 12 months compared with 14.5% of those between ages 75 and 84. Furthermore, few studies on technology use in older adults have examined whether use patterns vary by health and functional status. In one study looking at computer access and internet use among older adults, Wright and Hill (2009), using data from the 2003 Current Population survey, found significantly lower usage rates among older adults with disabilities, based on vision, hearing, physical mobility, hand/finger dexterity, and homebound status, compared with those without (17% vs. 37%). More recent data on technology usage data among older adults with disabilities have not been described.

Multiple theoretical frameworks have been proposed for technology adoption. Originally developed in the context of technology adoption in the workplace, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) by Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, and Davis (2003) incorporated eight previous models used to understand technology acceptance and has recently been applied in the context of older adult adoption of technology (Mallenius, Rossi, & Tuunainen, 2007; Nägle & Schmidt, 2012; Or et al., 2011). The UTAUT model consists of four determinants of behavioral intention leading to use behavior: performance expectancy (defined by perceived usefulness and relative advantage over previous technology), effort expectancy (encompassing perceived ease of use, complexity, and ease of use), social influence (social norms), and facilitating conditions with four moderators (gender, age, experience, voluntariness of use). Though multiple models exist to explain technology adoption, the constructs from the UTAUT provide a tested theoretical framework for technology adoption by older adults.

A better understanding of technology usage among older adults may help direct future interventions aimed at improving the health and quality of life of this rapidly growing segment of the population. As major public health agencies, such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control, proceed with the development of health promotion and education programs based on new technologies, there is a clear need to characterize variation in technology use in the older adult population. Accordingly, the aims of the current study were to (a) examine technology use patterns among older adults by demographic and health characteristics; (b) determine internet usage patterns for personal tasks and health-related tasks; and (c) determine technology usage patterns in older adults with and without disabilities. We hypothesized that the majority of older adults use these technologies. Given the relevance of technology to common activities (e.g., communication, banking) and evidence for improvements in social isolation and health outcomes, we expected that the perceived usefulness and relative advantage over previous technologies, as encompassed by the UTAUT determinant of performance expectancy, would result in more older adults using technology. We also hypothesized that the older age groups and those with disability or impairment would have lower usage than younger age groups and those without impairment. Based on the UTAUT, we anticipate effort expectancy, as characterized by complexity and ease of use, to be congruent with previous reports of interface issues and lack of training and support resulting in decreased technology adoption.

Design and Methods

Study Population

The data analyzed were from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). The NHATS is sponsored by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG032947) and was conducted by the Johns Hopkins University. A nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries was recruited to examine late-life disability trends and advance understanding of late-life functional changes in U.S. adults ages 65 and older (Kasper & Freedman, 2012). The Medicare enrollment database served as the sampling frame. Using an age-stratified, three-stage sample design, 8,245 participants were enrolled in the study with participants selected from 5-year age groups between the ages of 65 and 90 and from persons ages 90 and older. The response rate was 71%. Proxy respondents were used in instances where participants could not respond (e.g., in cases of dementia, cognitive impairment, severe illness, speech impediment). All participants, or their proxy respondents, provided written informed consent. Analytic weights were assigned to all participants to adjust for nonresponse and oversampling of the oldest-old and black non-Hispanic persons.

Participants or their proxies, living in the community or residential care facilities except nursing homes were interviewed by trained research staff in their homes. Interviews were standardized with primarily closed-ended questions. Facility audits but not in-person interviews were conducted for the 468 (5.7%) nursing home residents who were not expected to return to their previous residence. These participants were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, 168 (2.0%) nonnursing home residential care participants did not complete the in-person interview and were also excluded from analysis. The analytical weights for the remaining respondents were adjusted to account for those without interviews. The final sample size consisted of 7,609 community-dwelling older adults.

Measures

Demographic variables collected during the interview included age, sex, race and ethnicity, education level, and marital status. Age was collapsed to categorical levels in 5-year increments, and race/ethnicity information was condensed to four categories (white-non-Hispanic, black-non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and Other).

Health-related variables collected during the interview included self-rated health status (“Would you say that in general your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”) and medical diagnoses by a physician. To capture level of multimorbidity, a total count was calculated from the number of diagnoses reported (scale: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5). Additional items inquired if vision, hearing, pain, breathing difficulties, or altered balance and co-ordination limited participation in usual activities during the last month. A measure of cognitive status was constructed from two variables: (a) reported memory problems interfering with daily activities two or more days per week or (b) a reported diagnosis of dementia. Participants with proxy respondents but no diagnosis of dementia were not included, as memory was not measured in a comparable way to the other participants.

An index of physical capacity was constructed from six variables (ability to walk three blocks independently, ability to climb 10 stairs independently, and ability to carry 10 pounds independently, ability to bend over, ability to reach overhead, and ability to grasp or handle small objects). The original index by Freedman and colleagues (2011) assessed six pairs of less and more challenging tasks to capture a wide range of functional ability. For the current study, the six less challenging tasks were collapsed to indicate a range in ability on a 4-point scale (0 = able to do all six tasks; 1 = unable to do 1–2 tasks; 2 = unable to do 3–4 tasks; 3 = unable to do 5–6 tasks).

Disability status was assessed based on difficulty and/or assistance needed to complete basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and for mobility outside the home. In the interview, participants were asked how much difficulty they had with self-care ADL tasks (eating, bathing, dressing, getting out of bed, and toileting) and whether they received help to complete each ADL. These responses were combined to indicate if a participant (a) had difficulty with any of the five ADLs (yes/no), and (b) required help to complete any of the five ADLs. The responses from these two derived variables were then combined as a single, hierarchical measure of ability to complete ADLs spanning from “No difficulty completing or help needed for any ADLs” (0) to “Difficulty completing but no help needed for any ADLs” (1) to “Help needed for any ADLs” (2). The same procedure was used to construct an index for mobility outside the home based on participant responses to the sequential questions: “No difficulty or help needed with mobility outside the home” (0), “Difficulty completing but no help needed with mobility outside the home” (1), and “Help needed for mobility outside the home” (2).

Participants were asked up to 13 questions related to use of technology for communications. Participants were asked in the last month whether they had sent messages by e-mail or text, gone on the internet or online for any reason, gone on the internet or online to shop for groceries or personal items, to pay bills or do banking, or to order or refill prescriptions (response options: yes/no). They were also asked whether in the last year they used the internet or went online to contact medical providers, handle Medicare or other health insurance matters, or to get information about health conditions (response options, yes/no). Responses to reasons for use of the internet were combined to create two unique, dichotomous variables: (a) internet usage for personal tasks such as banking or shopping for groceries or personal items, and (b) internet usage for health-related tasks such as communication with insurance or a health care provider, prescriptions, or health-related information seeking. Participants were also asked about frequency of sending messages by e-mail or text (response options: most days, some days, rarely), if they had access to computers both inside and outside the home, and about cell phone ownership (yes/no).

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata (Version 12.1 Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Analytic sample weights were used to adjust for nonresponse and oversampling of subgroups. Taylor series linearization was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI). Prevalence of e-mail or text messaging for communication, use of the internet in general, and use of the internet for personal tasks and health-related tasks were estimated for the population as a whole and by demographic characteristics and disability status. Differences in technology use by demographic and health-related characteristics were evaluated using the adjusted Wald statistic. Poisson regression was used to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% CI for technology usage by disability status. Sociodemographic characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status were included in the models as covariates as well as self-rated health and multimorbidity.

Results

Based on the analysis of nationally representative data from the NHATS, in 2011, 63.2% of older adults in the United States had access to a computer and 75.9% reported owning a cell phone. Of those with a cell phone, 11.3% did not have a landline in the home. Overall, 47% reported using e-mail, text messaging, or the internet in the last month. The prevalence of using e-mail or text messaging for communication in the last month was 40.2% and 42.7% reported accessing the internet for reasons other than e-mail. As shown in Table 1, both internet use and e-mail/text messaging were associated with younger age, male sex, white race, higher education level, and being married (all p values < .001). Higher self-rated health status was significantly associated with higher technology usage, (p < .001) with 63% of those rating their health as “Excellent” using e-mail or text messaging compared with 16% of those rating themselves as having “poor” health status. Similarly, a higher level of multimorbidity was associated with less use of the internet and e-mail or text messaging in the last month. After adjusting for age, the technology use patterns shown in Table 1 held for all variables except that the difference between men and women in e-mail and text messaging was no longer statistically significant.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics and Prevalence of Technology Use in the Past Month

| Total population, % (CI) | E-mail/text, % (CI) | Use internet % (CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (n = 7,609) | 40.2 (38.3–42.1) | 42.7 (40.8–44.7) | |

| Age | |||

| 65–69 | 27.9 (26.9–29.0) | 58.7 (55.2–62.0) | 63.3 (60.0–66.5) |

| 70–74 | 25.0 (24.1–25.8) | 47.5 (44.3–50.8) | 50.3 (46.5–54.1) |

| 75–79 | 19.1 (8.2–19.9) | 32.3 (30.1–34.7) | 35.5 (32.9–38.1) |

| 80–84 | 14.7 (14.0–15.4) | 26.0 (23.2–29.1) | 26.4 (23.5–29.6) |

| 85–89 | 9.1 (8.5–9.8) | 16.7 (14.2–19.5) | 15.7 (13.2–18.6) |

| ≥90 | 4.3 (3.8–4.7) | 10.3 (7.9–13.2)* | 9.4 (7.3–12.1)* |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 43.4 (42.0–44.8) | 42.8 (40.0–45.5) | 47.0 (44.6–49.4) |

| Female | 56.6 (55.2–58.0) | 38.2 (36.0–40.5)** | 39.4 (37.1–41.8)* |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 80.5 (78.8–82.2) | 44.7 (42.5–46.9) | 47.4 (45.0–49.7) |

| Black | 8.1 (7.3–9.0) | 19.9 (16.8–23.3) | 22.3 (19.4–25.6) |

| Hispanic | 6.7 (5.8–7.9) | 18.8 (13.4–23.6) | 20.0 (14.9–26.3) |

| Other | 4.6 (3.7–5.8) | 29.9 (23.6–37.0)* | 30.9 (23.8–39.0)* |

| Education level | |||

| <9 years | 10.4 (9.2–11.7) | 4.9 (3.1–7.7) | 5.5 (3.88.0) |

| 9–11 years | 11.4 (10.4–12.4) | 13.0 (10.3–16.3) | 14.6 (11.5–18.4) |

| High school graduate | 27.6 (26.3–28.9) | 27.3 (24.9–29.9) | 30.5 (27.4–33.7) |

| Some college/vocational | 26.2 (25.0–27.5) | 51.8 (48.5–55.1) | 55.3 (52.2–58.3) |

| College graduate | 13.0 (11.8–14.4) | 66.7 (63.6–69.8) | 68.1 (65.3–70.8) |

| Advanced degree | 11.3 (10.0–12.8) | 75.0 (71.4–78.2)* | 77.8 (74.8–80.4)* |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living together | 57.0 (55.5–58.4) | 48.5 (46.0–50.9) | 51.9 (49.5–54.3) |

| Separated/divorced | 12.2 (11.4–13.2) | 40.2 (36.3–44.2) | 41.4 (36.8–46.2) |

| Widowed | 27.1 (25.8–28.3) | 24.8 (22.6–27.2) | 25.8 (23.1–28.7) |

| Never married | 3.7 (3.2- 4.4) | 25.7 (19.6–32.9)† | 30.4 (24.2–37.4)† |

| Multimorbidity | |||

| 0 | 9.6 (8.9–10.3) | 49.2 (45.3–53.1) | 51.5 (46.6–56.4) |

| 1 | 19.4 (18.4–20.4) | 49.9 (46.7–53.1) | 51.5 (48.1–54.9) |

| 2 | 24.8 (23.7–26.0) | 42.2 (39.2–45.4) | 44.7 (41.6–47.8) |

| 3 | 21.6 (20.6–22.7) | 38.4 (35.0–41.9) | 41.4 (38.5–44.4) |

| 4 | 13.0 (12.1–14.0) | 31.0 (27.1–35.2) | 33.4 (30.1–36.9) |

| 5 or more | 11.5 (10.7–12.4) | 25.8 (22.8–28.9)* | 29.3 (26.1–32.8)* |

| Self-rated health status | |||

| Excellent | 14.8 (13.7–15.9) | 61.4 (58.0–64.8) | 63.4 (60.3–66.5) |

| Very good | 29.5 (28.3–30.8) | 52.5 (49.8–55.2) | 54.6 (51.6–57.5) |

| Good | 30.7 (29.4–32.0) | 34.8 (32.8–36.9) | 37.7 (35.4–40.1) |

| Fair | 18.4 (17.3–19.5) | 21.0 (18.2–24.1) | 24.6 (21.9–27.5) |

| Poor | 6.7 (6.0–7.5) | 16.4 (13.1–20.4)* | 17.7 (14.5–21.6)* |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

* p < .001. ** p < .01.

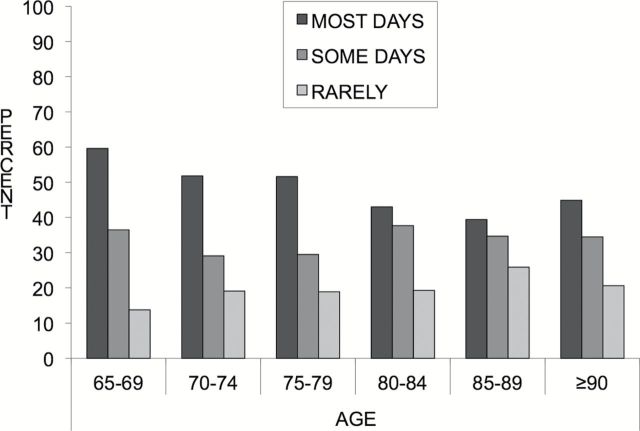

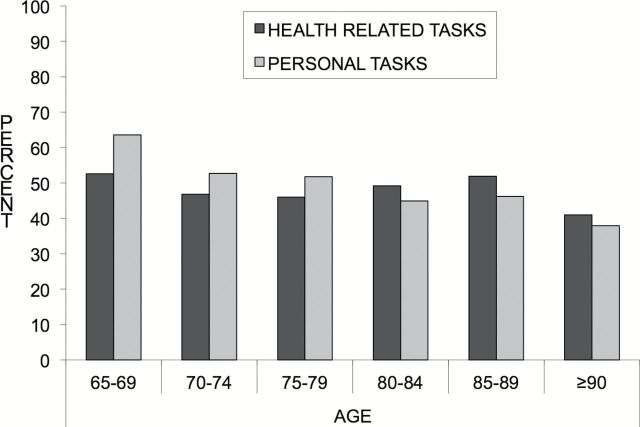

Frequency of e-mail or text messaging and frequency of using the internet for health-related and personal tasks generally decreased with advancing age. Among those who used e-mail or text messaging for communication, 59.6% of those ages 65–69 used these technologies on most days compared with less than 45% of those 85 years and older (Figure 1). Among those who access the internet, the prevalence of internet use for personal tasks such as shopping or banking was 56%, whereas 49.4% reported using the internet for health-related tasks. As shown in Figure 2, younger cohorts use the internet for personal tasks more than older cohorts, but older cohorts use the internet for health-related tasks more than personal tasks.

Figure 1.

Frequency of e-mail or text messaging in the past month among those who e-mail or text.

Figure 2.

Use of internet for health-related and personal tasks among internet users in the past month.

Results from the multivariate analysis of technology usage by level of physical capacity and disability status are presented in Table 2. All models were adjusted for sociodemographic factors, self-rated health status, and multimorbidity. Generally, those with more impairment were less likely to use e-mail/text messaging or use the internet for personal tasks across the three different measures (physical capacity, ADLs, mobility). However, there was no difference in internet use for health-related information by level of ADL dependence; whereas those needing help with outdoor mobility or with less physical capacity were less likely to use the internet for health-related information. Those with lower scores on the physical capacity index had lower usage of the internet for personal (PR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.30–0.65) and health-related tasks (PR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.30–0.56) after adjusting for sociodemographic and health factors.

Table 2.

Prevalence Ratio for E-mail and Text Messaging and Categorical Internet Use in the Past Month by Disability Status

| E-mail/text PR (95% CI) | Internet use for health-related tasks PR (95% CI) | Internet use for personal tasks PR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported physical capacity | |||

| 0 (Able to do all 6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 (Unable to do 1–2) | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | 0.95 (0.82–1.11) | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) |

| 2 (Unable to do 3–4) | 0.70 (0.59–0.83) | 0.79 (0.63–0.99) | 0.68 (0.54–0.85) |

| 3 (Unable to do 5–6) | 0.49 (0.36–0.66) | 0.47 (0.30–0.56) | 0.44 (0.30–0.65) |

| ADLsa | |||

| No difficulty/help | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Difficulty | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 0.99 (0.86–1.03) | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) |

| Help needed | 0.67 (0.59–0.76) | 0.82 (0.66–1.03) | 0.77 (0.64–0.94) |

| Mobility outside the home | |||

| No difficulty/help | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Difficulty | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | 1.17 (0.95–1.44) | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) |

| Help needed | 0.58 (0.50–0.68) | 0.77 (0.60–0.98) | 0.69 (0.56–0.86) |

Notes: All models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, multimorbidity, and self-rated health status. CI = confidence interval; PR = prevalence ratio.

aADLs includes eating, bathing, toileting, dressing, and getting out of bed.

Comparisons of technology use by different health impairments and symptoms are presented in Table 3. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, multimorbidity, and self-rated health status. Technology use did not vary by the presence of hearing impairment or balance or co-ordination impairments. Technology use was 20%–34% higher in those with breathing difficulties (e.g., use of e-mail/text; PR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.08–1.33) and pain that limits function (e.g., use of internet for health-related tasks; PR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.21–1.48). Impairments in vision and memory were associated with decreased usage of e-mail and text messaging and the internet.

Table 3.

Prevalence Ratio for E-mail and Text Messaging and Categorical Internet Use in the Past Month by Activity-Limiting Impairments and Symptoms

| Impairment or symptom | E-mail/text PR (95% CI) | Internet use for health-related tasks PR (95% CI) | Internet use for personal tasks PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vision | 0.69 (0.58–0.82) | 0.44 (0.32–0.59) | 0.58 (0.44–0.77) |

| Hearing | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | 0.96 (0.81–1.15) | 1.00 (0.82–1.21) |

| Breathing | 1.20 (1.08–1.33) | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) | 1.24 (1.03–1.51) |

| Pain | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 1.34 (1.21–1.48) | 1.22 (1.11–1.34) |

| Balance/co-ordination | 0.87 (0.78–0.99) | 0.98 (0.81–1.17) | 0.93 (0.79–1.08) |

| Memory interferes ≥ 2×/week (n = 7,194) | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) |

Notes: All models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, multimorbidity, and self-rated health status. CI = confidence interval; PR = prevalence ratio.

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative study of older adults in 2011, the use of technology for communication and access to the internet among older adults was highly stratified by age, sex, education level, race/ethnicity, and marital status as well as by physical capacity and disability status. Use of the internet was highest in the younger age groups, with more than 50% of those ages 65–74 using the internet compared with less than 10% of those ages 90 and older. Additionally, more than 50% of those with some vocational training or college reported use of e-mail or text messaging compared with 13% or less in those without a complete high school education. After adjusting for age, a similar proportion of men and women used e-mail and text messaging; however, a higher proportion of men reported using the internet compared with women.

Technology use, and the reasons for use, varied by physical capacity and disability status. After controlling for sociodemographic and health factors, those with relatively better physical capacity and less severe disability appeared to use the internet and e-mail/text messaging for communication at similar rates to those without disability or impaired physical capacity. However, those with more severe disability such as requiring help to perform ADLs or mobility outside the home used technology at significantly lower rates. Similarly, e-mail and internet use decreased with increased physical capacity impairment. Technology use also varied by activity-limiting symptoms and impairments. In particular, older adults with vision and memory impairment were less likely to use technology compared with those without these impairments. Recent studies of technology use among the visually impaired have identified multilevel barriers including policies that do not explicitly support accessible design, webpage design and limitations for interpretation by assistive devices, and lack of financial resources to acquire appropriate assistive technology (Hollier, 2007; Murphy, Kuber, McAllister, Strain, & Yu, 2008). Within the framework of the UTAUT model, the constructs of effort expectancy and facilitating conditions, or lack thereof, may best explain lower technology use among those with more severe physical impairment and with vision and memory impairment. Barnard, Bradley, Hodgson, and Lloyd (2013) found facilitating conditions to be critical for new technology learning by older adults. Additional research is needed to understand if the provision of additional support and training and/or alternative interface designs would increase technology use in these populations of older adults.

Other impairments or symptoms, such as pain or difficulties with breathing, were associated with increased likelihood of technology use. The higher prevalence of technology use among older adults with activity-limiting pain and breathing limitations may be indicative of how technology can enhance communication and personal or health-related tasks in those with functional limitations. Further research is needed to better understand the differential use of technology by type of impairment. One potential area for exploration includes assessment of whether the barriers associated with accomplishing tasks off-line (e.g., leaving the house, navigating multiple environments for social, personal, or health care reasons) are greater in comparison to the barriers associated with accomplishing the same tasks using technology. In other words, does performance expectancy as posited by the UTAUT (i.e., perceived usefulness and relative advantage) mitigate the choice to use technology at higher rates in this group of older adults. Given the higher rate of internet use for health-related tasks among those with activity-limiting pain, it is worth examining if these older adults have a need of more frequent interaction with health care providers and services (e.g., prescription refills, medical specialist appointments, physiological monitoring) that can be facilitated through technology or in contrast, if older adults with activity-limiting pain are searching for health-related information online not currently provided by the traditional health care system.

Overall, the prevalence of e-mail and internet use in the NHATS is somewhat lower than recent estimates from the Pew Research Center (47% vs. 53%, respectively) (Zickuhr & Madden, 2012). This discrepancy may be in part due to sampling differences, that is, oversampling of the oldest-old and black older adults in the NHATS, sample size differences, and variation in question wording. For example, in the NHATS, participants were asked about technology use in the last month, whereas the questions used in the Pew survey do not specify a particular time period. Findings from the NHATS are more similar to those reported by the Economics and Statistics Administration based on analysis of the 2010U.S. Census Current Population Survey (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2011) with 42.7% vs. 41.6%, respectively, for internet use and 63.2% vs. 61.0% for having access to a computer.

It appears the percentage of older adults currently accessing the internet, 42.7% based on the NHATS, is higher compared with 10 years ago when an estimated 37% of older adults accessed the internet, based on the 2003 Current Population survey (Wright & Hill, 2009). However, it is still not utilized by the majority of older adults. Further examination is warranted, of how barriers to technology adoption relate to the constructs of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions of the UTAUT. In a study of home care patient’s acceptance of web-based self-management technology, performance expectancy (perceived usefulness) was indirectly influenced by social influence and perceived ease of use and accounted for 54% of the variability in behavioral intention (Or, 2011). In evaluating older adults’ acceptance of wireless sensor networks to assist health care in older adults, Steele, Lo, Secombe, and Wong (2009) also found evidence for the importance of social influence and perceived usefulness in acceptance of a new technology but cost was the most predominant determinant. Conversely, a slightly higher percentage of older adults reported owning a cell phone in the NHATS sample compared with the Pew findings (69% vs. 73%), which is consistent with trends in rising cell phone ownership rates (CTIA, 2012). In a qualitative study of mobile device adoption in older adults, using the UTAUT model, Mallenius, Rossi, and Tuunainen (2007) found strong interest for mobile devices stemming from social influence of family members, but a lack of facilitators such as easy to use keyboards or readable instruction manuals. Longitudinal studies are needed to identify if social influence will be sufficient to engage more older adults in mobile phone adoption or if issues around cost, lack of facilitators, and effort expectancy will limit mobile phone use.

Based on the current stratification of technology use among older adults, those who have traditionally been marginalized from access to health care and health information continue to be disadvantaged in electronic and mobile campaigns. Older adults who do not use technology may miss opportunities to receive important communications (e.g., public health messages in emergencies), social connection (Thackeray, Neiger, Smith, & Van Wagenen, 2012), and even social security benefits as the government moves exclusively to electronic banking (U.S. Social Security Administration, 2013). For these reasons, it is still important to employ a range of communication options to engage older adults in health promotion and education from print, mail, and in-person communication to online and mobile platforms. Of note, in a qualitative study of use of and satisfaction with sources of health information among older adults, Taha, Sharit, and Czaja (2009) found little difference in satisfaction with health care information between internet and noninternet users. This suggests that future adoption of technology may remain stratified if the potential benefits of internet use are not readily apparent to current nonusers. At the same time, additional consideration is needed for how technology use can be spread to more older adults to help reduce disparities. For example, recent studies show reduced social isolation (Cotten, Anderson, & McCullough, 2013), improvements in glycemic control in diabetic older adults (Lim et al., 2011), and reduced hospitalizations for older adults with heart failure after randomization to ehealth and mhealth interventions (Scherr et al., 2009). Given the finding of higher self-rated health status being associated with technology use from the NHATS, future technology-based interventions targeting chronic illness and frailty will also need to take accessibility and training into consideration.

Acceptance and adoption of technology has implications beyond an alternative means of communication for older adults. Assistive technology for older adults and those with disabilities also includes behavior monitoring technology, smart home applications, and telehealth interventions. Within the context of long-term care, technological applications include ambient assisted living, and electronic interface solutions between health and social care professionals, and between formal and informal caregivers (Billings, Carretero, Kagialaris, Mastroyiannakis, & Meriläinen-Porras, 2013). In a review by Blaschke, Freddolino, and Mullen (2009), preliminary but positive evidence was found around benefits for assistive technology in caregivers of older adults with respect to support, information, and reduced burden. However, Demiris and Hensel (2008) reviewed studies of smart home applications and found little evaluation of changes in health outcomes as a result of such interventions. Evaluation of telehealth interventions is mixed with positive impacts shown for glycemic control and health services usage (Polisena et al., 2009), lower mortality, and emergency admission rates (Steventon et al., 2012), but no change in quality of life or psychological outcomes for patients with particular chronic diseases (Cartwright et al., 2013). In light of these previous findings and the results from the NHATS study, there are important policy and practice implications to consider for older adults. What is currently unknown is whether rates of technology use in older adults with more severe physical impairment, reduced vision and memory impairment have decreased as a consequence of change in severity of disability or if they never adopted cell phone and computer technology at all. This raises several questions: (a) Does technology need to adapt more readily to changes in users abilities? (b) Is there a time when the relevance of technology does not exceed the cost in terms of effort or perceived benefit in the aging process? and (c) Would older adults with past computer/cell phone experience be more receptive to behavioral monitoring or telehealth interventions compared with those who have limited or no experience with newer technologies. The plan to reassess and interview participants in the NHATS longitudinally should provide more insight in this area in the coming years. In the meantime, it will be necessary for health practitioners and policy makers to weigh the benefits of communication through computers and cell phones with the cost of lower reach to a significant portion of the older adult population (i.e., the oldest-old and those with disability).

The current study had several strengths and limitations. The use of multiple measures for impairment and disability is a strength of the NHATS data collection instrument and provides more nuanced detail to describe older adult technology users. The selection of a representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older, including use of proxy respondents in cases where participants could not respond, allows for generalizability of the results. The study was limited by the design of the questions related to technology use. There is some evidence to show differentiation between use of mobile technology versus traditional computers, with increasing numbers of people having access to the internet and e-mail through mobile phones. The 2011 NHATS survey did not differentiate between modes of access to the internet. Further, the survey questions did not ask participants to differentiate by the type of cell phone owned. More in-depth questions and research are needed to better describe the specific types of technology used by older adults and specific reasons for their use.

Despite increasing ownership rates of cell phones and computers among older adults, a large segment of this population does not currently use e-mail or text messaging or access the internet. Although mhealth and ehealth programs hold promise for closing the health care access and information gap, the results from the current study show there is limited technology use among those who may be able to benefit the most from such programs. Continued tracking of technology use among older adults is needed to assess how newer technologies are incorporated and to better understand financial and health outcomes from lack of technology use among the majority of older adults.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Institute on Aging (T32 AG027677). The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG32947) and was conducted by the Johns Hopkins University.

References

- Barnard Y., Bradley M. D., Hodgson F., Lloyd A. D. (2013). Learning to use new technologies by older adults: Perceived difficulties, experimentation behaviour and usability. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 1715–1724. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.006 [Google Scholar]

- Beach S.R., Schulz R., Downs J., Matthews J., Barron B., Seelman K. (2009). Disability, age, and informational privacy attitudes in quality of life technology applications: Results from a national web survey. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing (TACCESS), 2, 1–21. 10.1145/1525840.1525846 [Google Scholar]

- Billings J., Carretero S., Kagialaris G., Mastroyiannakis T., Meriläinen-Porras S. (2013). The role of information technology in LTC for older people. In Leichsenring K., Billings J., Nies H. (Eds.), Long-Term Care in Europe – Improving Policy and Practice (pp. 252–277). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke C. M., Freddolino P. P., Mullen E. E. (2009). Ageing and technology: A review of the research literature. British Journal of Social Work, 39, 641–656. 10.1093/bjsw/bcp025 [Google Scholar]

- Boulton-Lewis G. M., Buys L., Lovie-Kitchin J., Barnett K., David L. N. (2007). Ageing, learning, and computer technology in Australia. Educational Gerontology, 33, 253–270. 10.1080/03601270601161249 [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B. D., Buday S. (2007). Computer use among older adults in a naturally occurring retirement community. Computers in Human Behavior, 2, 3012–3024. 10.1016/j.chb.2006.08.015 [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright M., Hirani S. P., Rixon L., Beynon M., Doll H., Bower P., et al. Newman S. P. Whole Systems Demonstrator Evaluation Team. (2013). Effect of telehealth on quality of life and psychological outcomes over 12 months (Whole Systems Demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study): Nested study of patient reported outcomes in a pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 346, f653. 10.1136/bmj.f653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N. (2011). Relationship between health service use and health information technology use among older adults: Analysis of the U.S. National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13, e33. 10.2196/jmir.1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K., Doblhammer G., Rau R., Vaupel J. W. (2009). Ageing populations: The challenges ahead. Lancet, 374, 1196–1208. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten S. R., Anderson W. A., McCullough B. M. (2013). Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15, e39. 10.2196/jmir.2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CTIA—The Wireless Association. (2012). Retrieved December 14, 2012, from http://www.ctia.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S. J., Lee C. C. (2007). The impact of aging on access to technology. Universal Access in the Information Society, 5, 341–349. 10.1007/s10209-006-0060-x [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G., Hensel B. K. (2008). Technologies for an aging society: A systematic review of “smart home” applications. Yearbook of medical informatics, 47(Suppl. 1), 33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S., Duggan M. (2012). Mobile Health 2012. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 12, 2012, from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Mobile-Health/Main-Findings/Mobile-Health.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman V. A., Kasper J. D., Cornman J. C., Agree E. M., Bandeen-Roche K., et al. Wolf D. A. (2011). Validation of new measures of disability and functioning in the Naional Health and Aging Trends Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 66, 1013–1021. 10.1093/gerona/glr087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber T., Olazabal V., Brown K., Pablos-Mendez A. (2010). An agenda for action on global e-health. Health Affairs, 29, 233–236. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani C. A., Gruber-Baldini A. L., Park N. S., Schrodt L. A., Rokoske F., Sloane P. D., Zimmerman S. (2008). Physical performance characteristics of assisted living residents and risk for adverse health outcomes. The Gerontologist, 48, 203–212. 10.1093/geront/48.2.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J. M., Fried L. P., Simonsick E. M., Kasper J. D., Lafferty M. E. (1995). The Women’s Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women With Disability. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging. NIH publication 95–4009, appendix E. [Google Scholar]

- Heart T., Kalderon E. (2011). Older adults: Are they ready to adopt health-related ICT? International Journal of Medical Informatics, 82, e209–e231. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollier S. E. (2007). The disability divide: A study into the impact of computing and internet-related technologies on people who are blind or vision impaired. (pp.230–240) GLADNET Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Internet World Statistics (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2012, from http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

- Kasper J. D., Freedman V. A. (2012). National Health and Aging Trends Study Round 1 User Guide. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Lim S., Kang S. M., Shin H., Lee H. J., Yoon J. W., Yu S. H., et al. Jang H. C. (2011). Improved glycemic control without hypoglycemia in elderly diabetic patients using the ubiquitous healthcare service, a new medical information system. Diabetes Care, 34, 308–313. 10.2337/dc10-1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallenius S., Rossi M., Tuunainen V. K. (2007). Factors affecting the adoption and use of mobile devices and services by elderly people–results from a pilot study. 6th Annual Global Mobility Roundtable.

- Murphy E., Kuber R., McAllister G., Strain P., Yu W. (2008). An empirical investigation into the difficulties experienced by visually impaired Internet users. Universal Access in the Information Society, 7, 79–91. 10.1007/s10209-007-0098-4 [Google Scholar]

- Nägle S., Schmidt L. (2012). Computer acceptance of older adults. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation, 41(Suppl. 1), 3541–3548. 10.3233/WOR-2012-0633-3541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimrod G. (2009). Senior’s online communities: A quantitative content analysis. The Gerontologist, 50, 382–392. 10.1093/geront/gnp141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek M. A., Hughes R. B., Swedlund N., Taylor H. B., Swank P. (2003). Self-esteem and women with disabilities. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 1737–1747. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00169-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or C. K., Karsh B. T., Severtson D. J., Burke L. J., Brown R. L., Brennan P. F. (2011). Factors affecting home care patients’ acceptance of a web-based interactive self-management technology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 18, 51–59. 10.1136/jamia.2010.007336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polisena J., Tran K., Cimon K., Hutton B., McGill S., Palmer K. (2009). Home telehealth for diabetes management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 11, 913–930. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr D., Kastner P., Kollmann A., Hallas A., Auer J., Krappinger H., et al. Fruhwald F. M. MOBITEL Investigators. (2009). Effect of home-based telemonitoring using mobile phone technology on the outcome of heart failure patients after an episode of acute decompensation: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research, 11, e34. 10.2196/jmir.1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn N., Gorard S., Furlong J., Madden L. (2003). Older adults’ use of information and communication technology in everyday life. Ageing and Society, 23, 561–582. 10.1017/S0144686X03001302 [Google Scholar]

- Sourbati M. (2009). ‘It could be useful, but not for me at the moment’: Older people, internet access and e-public service provision. New Media & Society, 11, 1083–1100. 10.1177/1461444809340786 [Google Scholar]

- Steele R., Lo A., Secombe C., Wong Y. K. (2009). Elderly persons’ perception and acceptance of using wireless sensor networks to assist healthcare. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 78, 788–801. /10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steventon A., Bardsley M., Billings J., Dixon J., Doll H., Hirani S., et al. Newman S. Whole System Demonstrator Evaluation Team. (2012). Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: Findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 344, e3874. 10.1136/bmj.e3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha J., Sharit J., Czaja S. (2009). Use of and satisfaction with sources of health information among older internet users and nonusers. The Gerontologist, 49, 663–673. 10.1093/geront/gnp058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thackeray R., Neiger B. L., Smith A. K., Van Wagenen S. B. (2012). Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC public health, 12, 242. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (2011). Retrieved September 18, 2013, from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/exploring_the_digital_nation_computer_and_internet_use_at_home_11092011.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). Retrieved December 10, 2012, from http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2011/16.aspx.

- U.S. Social Security Administration. (2013) . Retrieved April 2, 2013, from http://www.ssa.gov/deposit/

- Venkatesh V., Morris M. G., Davis G. B., Davis F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS quarterly, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2011). mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies. Retrieved March 27, 2013, from http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wright D. W., Hill T. J. (2009). Prescription for trouble: Medicare Part D and patterns of computer and internet access among the elderly. Journal of Aging & SocialPolicy, 21, 172–186. 10.1080/08959420902732514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickuhr K., Madden M. (2012). Older adults and internet use. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved March 22, 2013, from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Older-adults-and-internet-use.aspx [Google Scholar]