Abstract

Background: Alemtuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody approved in several countries for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). This report summarizes the experience with infusion-associated reactions (IARs) in two phase 3 trials of alemtuzumab in RRMS and examines skilled nursing interventions in IAR prevention and management.

Methods: In the Comparison of Alemtuzumab and Rebif® Efficacy in Multiple Sclerosis (CARE-MS) studies, patients with RRMS (treatment naive [CARE-MS I] or with inadequate response [defined as at least one relapse] to previous therapy [CARE-MS II]) received intravenous infusions of alemtuzumab 12 mg/day on 5 consecutive days at baseline and on 3 consecutive days 12 months later. Patients were monitored for IARs during and after each infusion. An IAR was defined as any adverse event occurring during any infusion or within 24 hours after infusion.

Results: The IARs affected 90.1% of patients receiving alemtuzumab. The most common IARs were headache, rash, pyrexia, nausea, and flushing; most were mild to moderate in severity. Management of IARs consisted of infusion interruption or rate reduction, pharmacologic therapies, and continual patient education and support. Medication administration before and during alemtuzumab infusion reduced IAR severity. Forty-five of 972 alemtuzumab-treated patients (4.6%) required interruption of the first treatment course (ie, infusions did not occur on consecutive days); of these, 24 (53.3%) were still able to complete the first and second full treatment courses.

Conclusions: Nurses played an invaluable role in the detection and management of IARs in the CARE-MS studies. Best practices for management of IARs associated with alemtuzumab include patient and caregiver education, medication to lessen IAR severity, infusion monitoring, and discharge planning.

Alemtuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted to the cell surface protein CD52, is approved in several countries for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). CD52 is present at high levels on T and B lymphocytes and to a lesser extent on other immune cells. By binding to lymphocytes, alemtuzumab causes lysis and rapid depletion of these cells from circulation.1 Differential depletion and repopulation results in changes in the numbers, proportions, and properties of lymphocyte subsets, potentially leading to a rebalancing of the immune system2–4 that could contribute to the durable effects of alemtuzumab.5

A highly effective therapy, alemtuzumab has overall superior efficacy to that of subcutaneous (SC) interferon beta-1a, an established, efficacious treatment for RRMS.6,7 Alemtuzumab also has a well-described safety profile. As with most infused biologic therapies, infusion-associated reactions (IARs) are a frequently reported adverse event (AE) in alemtuzumab treatment.6,7

An understanding of how to detect and manage infusion-related AEs that may accompany the administration of alemtuzumab permits 1) diminution of the severity and number of these reactions, 2) improvement in patient care and comfort, and 3) delivery of the full intended dose.

Herein, we summarize the experience with IARs in the two phase 3 trials of alemtuzumab in RRMS and emphasize the important role of skilled nursing interventions in the prevention and management of IARs.6,7

Methods

Descriptions of the Comparison of Alemtuzumab and Rebif® Efficacy in Multiple Sclerosis (CARE-MS) I (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00530348) and II (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00548405) study protocols have been published elsewhere.6,7 Briefly, the CARE-MS program consisted of two randomized, rater-blinded, active-controlled, head-to-head, phase 3 trials comparing the safety and efficacy of alemtuzumab versus SC interferon beta-1a (Rebif, EMD Serono, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) in patients with RRMS who were treatment naive (CARE-MS I)6 or who had an inadequate response (defined as at least one relapse) to previous therapy (CARE-MS II).7 In both trials, patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive alemtuzumab 12 mg/day via intravenous (IV) infusions on 5 consecutive days at baseline and on 3 consecutive days 12 months later or SC interferon beta-1a 44 μg 3 times weekly during the 2-year treatment period. In CARE-MS II, randomization into a third treatment arm (alemtuzumab 24 mg) was discontinued early to increase enrollment in the 12-mg arm (and not for efficacy or safety reasons), and it was deemed exploratory for statistical purposes; however, safety findings, including IARs, from this arm are reported herein for completeness. Co-primary endpoints for both studies were annualized relapse rate and time to 6-month sustained accumulation of disability over 2 years.

Alemtuzumab was administered via IV infusions in a supervised medical setting. Patients being given alemtuzumab received daily infusions on 5 consecutive days at baseline (course 1: 12 mg daily [60 mg total] or 24 mg daily [120 mg total]) and on 3 consecutive days 12 months later (course 2: 12 mg daily [36 mg total] or 24 mg daily [72 mg total]). Each alemtuzumab infusion is given over approximately 4 hours. It is recommended that patients be observed for adverse reactions during and for 2 hours after each infusion. If not well tolerated, the infusion period could be extended at the physician's discretion, but the total infusion period on any day was not to exceed 8 hours.

At the physician's discretion, alemtuzumab dosing could be delayed due to an AE, such as an on-study relapse or infection, or could be interrupted for IAR management. If dosing was interrupted, the physician could make up the missed doses within 1 month (30 days) of that course's initiation. All alemtuzumab-treated patients received 1 g/day of IV methylprednisolone immediately before alemtuzumab administration on the first 3 days of treatment at baseline and 12 months later. Concomitant treatment with an antipyretic, antihistamine, or histamine H2 receptor blocker was permitted at the physician's discretion.

The CARE-MS studies conservatively defined an IAR as any AE beginning during or within 24 hours after an alemtuzumab infusion, regardless of relationship to treatment. As a consequence of this inclusive definition, not all IARs represent adverse reactions to alemtuzumab infusion, and administration-related events associated with SC interferon beta-1a injections were excluded.

Results

Patients

A description of CARE-MS I and II patients has been published previously6,7 and is summarized briefly here. In CARE-MS I, 581 patients were randomized and 91% completed the study on assigned treatment (362 taking alemtuzumab 12 mg and 164 taking SC interferon beta-1a 44 μg). Baseline characteristics of this study population were typical of patients with early, active, treatment-naive RRMS. In CARE-MS II, 840 patients were randomized and 85% completed the study on assigned treatment (399 taking alemtuzumab 12 mg, 158 taking alemtuzumab 24 mg, and 158 taking SC interferon beta-1a 44 μg). At baseline, compared with patients enrolled in CARE-MS I, CARE-MS II patients had slightly longer disease duration, higher baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale scores, and higher burden of disease. All CARE-MS II patients had previous exposure to interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, or both; less than 5% had previous monoclonal antibody therapy. Alemtuzumab showed efficacy superior to SC interferon beta-1a in CARE-MS I and II.6,7

Preparing for Infusion

Patient and caregiver education began before initiation of treatment with alemtuzumab and continued until after completion of all the infusions. Initial discussions were led by the treating physician, and key points were continually reinforced by nurses. Nurses discussed with patients the known risks associated with alemtuzumab therapy, as well as potential benefits of alemtuzumab with respect to MS activity and symptoms. Potential AEs were explained in detail, including those with onset in the short term (particularly IARs and infections) and the long term (autoimmune AEs, such as thyroid dysfunction, immune thrombocytopenia, and glomerular nephropathies, including anti–glomerular basement membrane disease).

Proactive education about IARs included information based on the results of a previous phase 2 study of alemtuzumab in patients with RRMS (CAMMS223 [NCT00050778])8 that most will be mild to moderate in severity and manageable with conventional oral medications. The recognition and management of potential allergic reactions, apart from expected IARs, were discussed with patients in detail. The importance of adequate hydration was stressed. Patients were informed of what to expect on infusion days via a written document that detailed the duration of infusions, medications that would be administered, and types of monitoring that would be performed (routine vital signs and skin examination). This allowed patients to plan personal and family activities, proper hydration and meals, and transportation accordingly. Patients with asthma were reminded to bring their inhaler on infusion days. Review of current medications was undertaken to ensure the prevention of overmedication, use of adequate birth control, evaluation of potential concomitant illness, and performance of appropriate laboratory pretesting.

Monitoring During Infusion, Overall Incidence of IARs, and Management

Patients were monitored throughout the 4-hour alemtuzumab infusion and for 1 to 2 hours after infusion. Monitoring comprised a combination of clinician vigilance and patient self-reporting based on the education they received before and during infusions. Symptoms of IARs and vital signs were assessed for nature and severity and were documented at least hourly throughout the infusion, with more frequent assessments if clinically indicated.

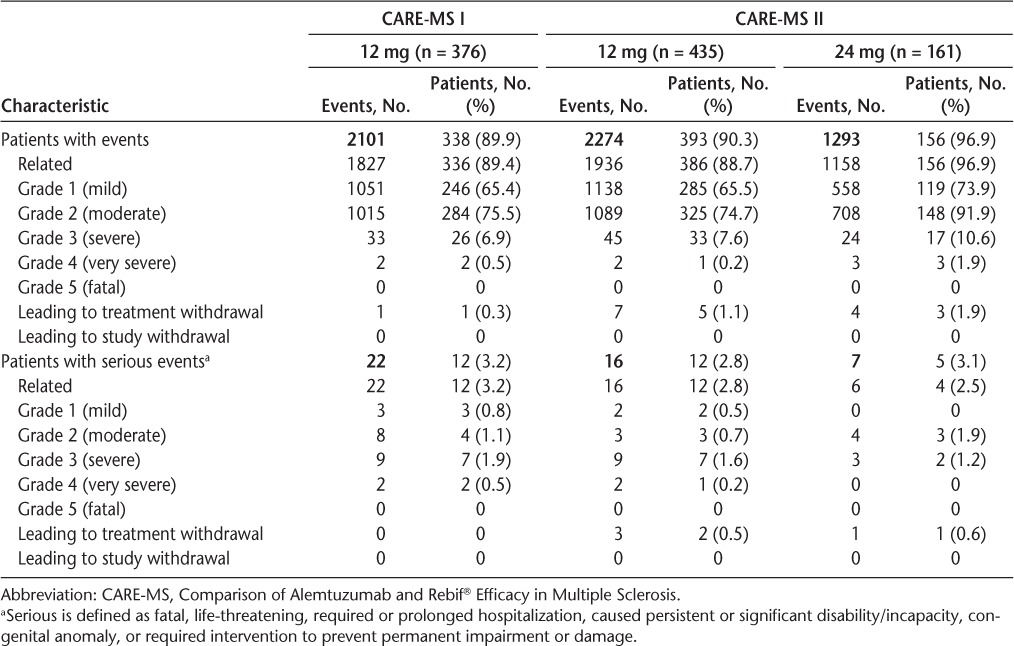

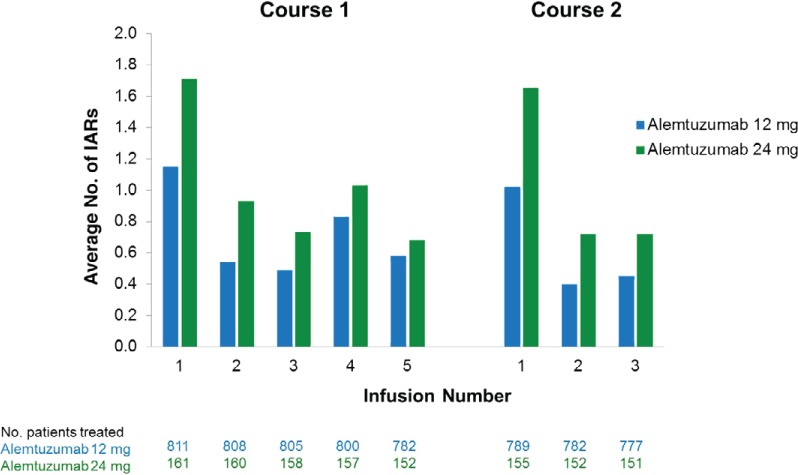

Alemtuzumab IARs were the most frequently reported category of AEs in alemtuzumab-treated patients, affecting 90.1% of those receiving alemtuzumab 12 mg in CARE-MS I and II and 96.9% of patients receiving 24 mg in CARE-MS II (Table 1). The IARs were more frequent during course 1 than during course 2 of treatment; IARs occurred in 84.7% (n = 687; 12 mg) and 96.3% (n = 155; 24 mg) of patients during course 1 compared with 68.6% (n = 541; 12 mg) and 81.9% (n = 127; 24 mg) of patients during course 2. In each treatment course, the greatest numbers of IARs occurred with the first infusion and decreased with each infusion thereafter (Figure 1). The exception was infusion 4 of course 1, which was the first infusion without corticosteroid premedication.

Table 1.

Overview of alemtuzumab infusion-associated reactions in CARE-MS patients

Figure 1.

Declining numbers of infusion-associated reactions (IARs) with each course and infusion of alemtuzumab in the Comparison of Alemtuzumab and Rebif® Efficacy in Multiple Sclerosis I and II (pooled data from both studies)

For the management of IARs, a combination of infusion interruption or rate reduction, pharmacologic therapies, and continual patient education and support were used until the IAR resolved. In addition to the 1 g of IV methylprednisolone that was routinely administered approximately 1 hour before alemtuzumab infusion on days 1, 2, and 3 at baseline and 12 months later, several other medications were administered or recommended to patients depending on individual needs or physician preference and practice. Medication to prevent IARs could be provided the day before, the morning of, during, or 1 hour after alemtuzumab infusions and after discharge from the infusion area. If a patient experienced a specific IAR and was successfully treated with a certain medication, that medication was often provided in a preventive manner on all subsequent infusion days. Such premedications could be taken at home before infusions or immediately before infusion administration.

Prevention and management of corticosteroid-induced AEs was an essential part of patient management. A low-sodium diet was emphasized to prevent corticosteroid-induced hypertension, avoidance of high-sugar foods was highlighted to prevent corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia, and prophylactic use of insomnia medications was offered.

Specific IAR Types and Their Management

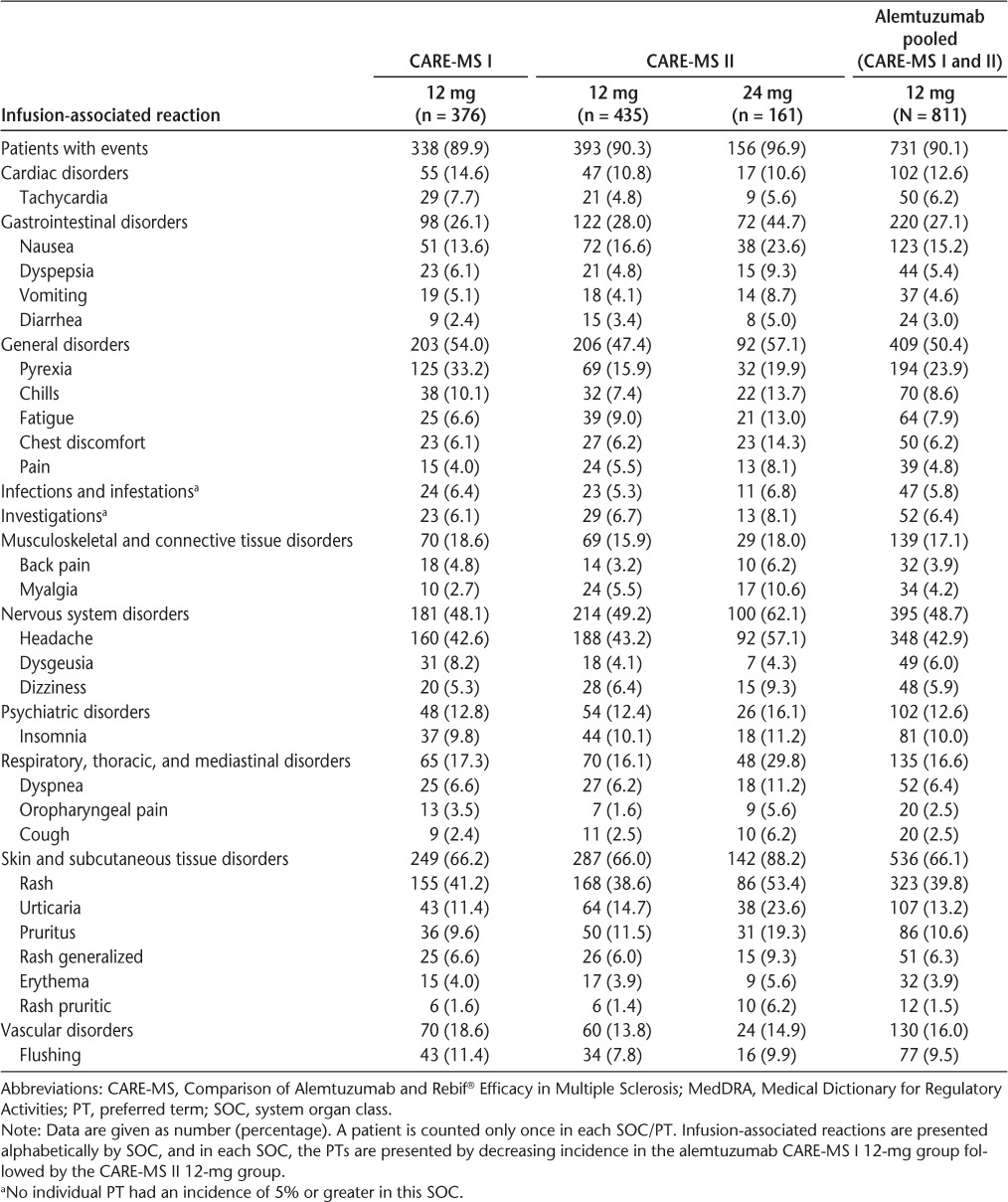

The IARs occurring in 5% or more of CARE-MS patients are presented in Table 2. There were no notable differences between the alemtuzumab 12- and 24-mg groups regarding the types of IARs, although incidences were generally higher in the 24-mg group.

Table 2.

Infusion-associated reactions occurring in 5% or more of CARE-MS patients by MedDRA SOC and PT

General disorders, including fatigue, aches/pains, and changes in body temperature, affected approximately half of the patients in each study. In this category, pyrexia was most common, followed by chills and fatigue. Nervous system disorders also affected approximately half of the patients in each study; this was primarily driven by headache, which was reported in 42.6% of CARE-MS I patients and 43.2% of CARE-MS II patients receiving alemtuzumab 12 mg. Antipyretic drugs, such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen, were provided to treat or prevent pyrexia, headache, and body aches.

Skin and SC tissue disorders composed some of the most commonly reported IARs, including rash, urticaria, and pruritus. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, cetirizine, fexofenadine, hydroxyzine, and loratadine, were provided to counteract rash, hives, and pruritus and were effective in doing so. H2 receptor antagonists, including ranitidine, cimetidine, and famotidine, were administered to maximize antihistaminic effect and to prevent or manage gastric AEs caused by some of the other medications.

A variety of gastrointestinal disorders occurred in each study, particularly nausea, which was reported in 13.6% of CARE-MS I patients and 16.6% of CARE-MS II patients receiving alemtuzumab 12 mg. Antiemetic agents, including ondansetron and prochlorperazine, helped to treat nausea.

Cardiac disorders also occurred in more than 10% of alemtuzumab-treated patients, with tachycardia being the most frequent (7.7% of CARE-MS I patients and 4.8% of CARE-MS II patients receiving alemtuzumab 12 mg). Other, less common events observed in this category included bradycardia and palpitations, which occurred in 3.1% and 2.9% of all alemtuzumab-treated CARE-MS patients, respectively. In addition, flushing, categorized under vascular disorders, affected approximately 10% of alemtuzumab-treated patients in each study.

The single documented case of a CARE-MS patient developing an anaphylactic IAR (a serious, grade 4 event occurring during the third alemtuzumab treatment course [first infusion of the CARE-MS II extension study in a patient who had received alemtuzumab in the core study]) was characterized by redness; swelling of the eyes, lips, hands, and face; itching and swelling in the mouth and throat; and coughing. Knowledge of the common signs and symptoms of allergic versus nonallergic (cytokine release) reactions was helpful in this assessment. The patient was treated with epinephrine, diphenhydramine, and oxygen via nasal cannula and recovered without sequelae.

Severity of IARs and Serious IARs

Most IARs were mild to moderate in severity. Severity of IARs was slightly greater in CARE-MS II patients who received alemtuzumab 24 mg (Table 1).

Severe IARs were managed primarily by slowing the infusion rate or by temporarily stopping the infusion, restarting it at a slower rate, and increasing to the optimum rate as tolerated. In 45 patients, the first treatment course was suspended/interrupted (alemtuzumab 12 mg, 33 patients; alemtuzumab 24 mg, 12 patients). Of these, 24 patients (53.3%) went on to eventually complete their first and second treatment courses (CARE-MS I alemtuzumab 12 mg, 10 patients; CARE-MS II alemtuzumab 12 mg, 8 patients; CARE-MS II alemtuzumab 24 mg, 6 patients); 3 patients (alemtuzumab 12 mg, n = 2; alemtuzumab 24 mg, n = 1) who experienced serious IARs during course 2 of treatment were not able to receive the complete second course. Overall, 97.5% of patients completed treatment courses 1 and 2. A physician was available at all times to assess and manage serious IARs. Three percent of patients (24 of 811) receiving alemtuzumab 12 mg experienced serious IARs (Supplementary Table 1). Serious IARs occurred more often during the first course of treatment (alemtuzumab 12 mg, 1.97%; alemtuzumab 24 mg, 2.48%) than during course 2 (alemtuzumab 12 mg, 1.27%; alemtuzumab 24 mg, 1.29%).

Postinfusion Management

After each infusion, patients and their caregivers received specific discharge plans, which included detailed information about the range of symptoms that might occur after infusion, what medications to take, and what symptoms required immediate emergency attention. Patients were provided with a written list of all medications taken on the day of the infusion, an explanation of why they were taken, the times of administration, and when the next dose could be taken. Patients were asked to record any symptoms they experienced after they were discharged and to contact the treating physician and nurse in case of an emergency.

For reducing the risk of herpetic infections, patients were sent home with a prescription for a 4-week supply of acyclovir or a therapeutic equivalent. Oral her pes (1.0%) and oral candidiasis (0.6%) were among the most common infections in alemtuzumab-treated patients. The rationale for use of and AEs associated with acyclovir were reviewed with the patients.

Other prescriptions that were optionally given to patients at discharge were for a 2-week supply of antihistamine and for antipyretics (or recommendations for over-the-counter alternatives). Antiemetics, narcotics, and sleep aids were optionally provided depending on individual patient needs.

Discussion

In the CARE-MS I and II studies, IARs composed a large proportion of all reported AEs. Most IARs were mild to moderate in severity. The number of IARs generally decreased with each annual course and with each subsequent infusion within a course. Many patients who discontinued infusions owing to IARs were able to resume and complete treatment courses.

Frequently, IARs are reported with infused therapies, with the two main types being allergic (hypersensitivity) and nonallergic (cytokine release) reactions.9 Allergic reactions are mediated by preformed immunoglobulin E (IgE) that triggers histamine release, and they have been seen with other infused monoclonal antibody therapies used to treat MS, including natalizumab10 and rituximab.11 Nonallergic reactions are commonly associated with a cytokine release syndrome involving interleukins, interferons, tumor necrosis factor, and other soluble factors released by immune effector cells or by target cells as they are destroyed.12 Several histamine-containing leukocyte cell types express CD52 and may be triggered by alemtuzumab treatment. Histamine release might occur, therefore, in both allergic and nonallergic alemtuzumab IARs.

Clues to whether a reaction is allergic or nonallergic may be found in the type, severity, and systemic nature of symptoms; timing of onset in relation to the infused dose; history of exposure to the agent (because a reaction can be allergic only after previous exposure); response to interruption of infusion; and, when available, response to rechallenge with the drug. Allergic reactions are often associated with cutaneous symptoms, including urticaria, angioedema, and flushing, and may also include respiratory symptoms and hypotension,12 but these also can occur in nonallergic reactions. The severity of allergic reactions is unpredictable; anaphylaxis can be life-threatening but was rare with alemtuzumab, with just one reported case during clinical studies.

Allergic reactions mediated by preformed IgE tend to occur immediately on infusion, although occasionally onset may be delayed.12,13 Onset of nonallergic reactions is variable but typically occurs within the first 2 hours of the infusion. Slowing or temporarily suspending the infusion often stabilizes or resolves the symptoms of nonallergic reactions, but allergic reactions likely require more active intervention.12 Nearly all alemtuzumab-related IARs seemed to be of nonallergic type. Few were severe or serious, onset was typically several hours after the start of infusion, and symptoms often responded to reducing the infusion rate. The fact that IARs most frequently occurred in patients with no previous exposure (ie, course 1) suggests these reactions were nonallergic because patients did not have detectable anti-alemtuzumab antibodies before exposure.6,7 The incidence and severity of IARs and serious IARs tended to decrease with the number of infusions, which also argues against sensitization by development of a specific IgE response. Contrary to what would be expected for an allergic hypersensitivity reaction, severe or serious IARs that occurred during the first alemtuzumab treatment course typically did not recur on rechallenge during the next treatment course.

The phenomenon of recurrence of previous MS relapse symptoms, typically lasting a few hours, was previously reported in association with alemtuzumab infusion.14 Routine corticosteroid premedication, previously shown to be effective in mitigating this effect14 and instituted in the alemtuzumab clinical development program largely for this purpose, kept the incidence of focal neurologic symptoms as IARs low. Given the frequency of IARs likely to be histamine mediated, the preventive or symptomatic use of antihistamine medications was also common.6,7

Because nurses have a unique perspective on patient learning and an ability to tailor education to individual patient needs, nurses played a particularly important role as educators during these trials. As with all clinical trials, the precise degree to which the safety findings from the CARE-MS studies will be applicable to the general MS population is not known. These studies enrolled selected treatment populations, and the dedicated resources that were used to collect information on IARs and to conduct various aspects of patient education and treatment may not always be available in infusion centers outside of clinical trials. In jurisdictions where alemtuzumab has been approved for the treatment of MS, it will be important for further research to follow the experiences of nurses in converting the specific educational, medication, and monitoring guidance developed from the CARE-MS studies into successful prevention and management of alemtuzumab-related IARs in real-world settings. To this end, a single-group, open-label, phase 4 trial (EMERALD [Evaluation of the Management of Infusion Reactions in Alemtuzumab-Treated Patients; NCT02205489]) is planned to assess the incidence, seriousness, severity, and nature of IARs in adult patients with RRMS for 30 days after each of two annual alemtuzumab treatment courses, which the patients will receive according to their local approved label. This study will provide an opportunity to evaluate comprehensive guidance that has been developed to assist in IAR management.15

Conclusion

Infusion-associated reactions were observed in a large proportion of all reported AEs for patients with RRMS being treated with alemtuzumab in the CARE-MS trials. Most IARs were mild to moderate in severity and were successfully managed with conventional oral therapies and without discontinuation of alemtuzumab therapy. The IARs can be reduced with several proactive measures, including patient education, oral hydration, premedication, and diligent monitoring. Skilled nursing interventions and support may improve the overall tolerability profile of alemtuzumab in the treatment of patients with RRMS.

PracticePoints.

Nursing interventions in the management of infusion-associated reactions (IARs) associated with alemtuzumab include continuous patient education, proper monitoring during infusion, thoughtful discharge planning, and reinforcing realistic expectations.

Appropriate use of prophylactic medications—particularly corticosteroids, antihistamines, and antipyretics—before, during, and after alemtuzumab infusion reduces the severity of IARs. The importance of adequate hydration needs to be emphasized.

Severe IARs can generally be managed primarily by slowing the infusion rate or by temporarily stopping the infusion, allowing time for recovery of symptoms, and restarting at a slower rate.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Jenna Hollenstein, a medical writer employed by Genzyme, a Sanofi company, and by Richard Hogan, PhD, of Evidence Scientific Solutions. Funding for Dr. Hogan's editorial support was provided by Genzyme, a Sanofi company.

Footnotes

From the Multiple Sclerosis Center and Neuroimaging Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA (CC); Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research, Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA (MN); Consultants in Neurology, Northbrook, IL, USA (CM); MS Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock, TX, USA (LM); and Genzyme, a Sanofi company, Cambridge, MA, USA (PO, DHM, MR).

Note: Supplementary material for this article is available on IJMSC Online at ijmsc.org.

Financial Disclosures: Ms. Caon has received honoraria from Genzyme as a consultant for advisory boards and a member of the speakers' bureau and serves as a consultant for the MS Atrium. Ms. Namey has received honoraria as a consultant for Genzyme and a member of the speakers' bureau for Genzyme. Ms. Meyer has received honoraria from Genzyme for consulting and participation in advisory board panels. Dr. Mayer has been a consultant for continuing medical education and non–continuing medical education services as a member of speakers' bureaus and advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies in the past 5 years; relationships with companies as a consultant include Acorda, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Genzyme, Novartis, Questcor, and Teva Neuroscience. Drs. Oyuela and Rizzo were employed at Genzyme during the development of the manuscript. Dr. Margolin is employed by Genzyme.

Funding/Support: CARE-MS I and II were sponsored by Genzyme, a Sanofi company, and by Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Hu Y, Turner MJ, Shields J et al. Investigation of the mechanism of action of alemtuzumab in a human CD52 transgenic mouse model. Immunology. 2009;128:260–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill-Cawthorne GA, Button T, Tuohy O et al. Long term lymphocyte reconstitution after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:298–304. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox AL, Thompson SA, Jones JL et al. Lymphocyte homeostasis following therapeutic lymphocyte depletion in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3332–3342. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson SA, Jones JL, Cox AL, Compston DA, Coles AJ. B-cell reconstitution and BAFF after alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coles AJ, Fox E, Vladic A et al. Alemtuzumab more effective than interferon beta-1a at 5-year follow-up of CAMMS223 clinical trial. Neurology. 2012;78:1069–1078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8ee7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen JA, Coles AJ, Arnold DL et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta-1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1819–1828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coles AJ, Twyman CL, Arnold DL et al. Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1829–1839. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61768-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coles AJ, Compston DAS, Selmaj KW et al. Alemtuzumab vs. interferon beta-1a in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1786–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namey M, Halper J, O'Leary S, Beavin J, Bishop C. Best practices in multiple sclerosis: infusion reactions versus hypersensitivity associated with biologic therapies. J Infus Nurs. 2010;33:98–111. doi: 10.1097/NAN.0b013e3181cfd36d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polman CH, O'Connor PW, Havrdova E et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:899–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown BA, Torabi M. Incidence of infusion-associated reactions with rituximab for treating multiple sclerosis: a retrospective analysis of patients treated at a US centre. Drug Saf. 2011;34:117–123. doi: 10.2165/11585960-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel WH. Infusion reactions: diagnosis, assessment, and management. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:E10–E21. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.E10-E21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung CH. Managing premedications and the risk for reactions to infusional monoclonal antibody therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:725–732. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coles AJ, Wing MG, Molyneux P et al. Monoclonal antibody treatment exposes three mechanisms underlying the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:296–304. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<296::aid-ana4>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ClinicalTrials.gov. Management of the infusion-associated reactions in RRMS patients treated with LEMTRADA (EMERALD) http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02205489.