Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Can a modified specific gravity technique be used to distinguish viable from nonviable embryos?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Preliminary data suggests a modified specific gravity technique can be used to determine embryo viability and potential for future development.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Single embryo transfer (SET) is fast becoming the standard of practice. However, there is currently no reliable method to ensure development of the embryo transferred.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

A preliminary, animal-based in vitro study of specific gravity as a predictor of embryo development using a mouse model.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

After a brief study to demonstrate embryo recovery, experiments were conducted to assess the ability of the specific gravity system (SGS) to distinguish between viable and nonviable embryos. In the first study, 1-cell mouse embryos were exposed to the SGS with or without previous exposure to an extreme heat source (60°C); measurements were repeated daily for 5 days. In the second experiment, larger pools of 1-cell embryos were either placed directly in culture or passed through the SGS and then placed in culture and monitored for 4 days.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

In the first experiment, viable embryos demonstrated a predictable pattern of descent time over the first 48 h of development (similar to previous experience with the SGS), while embryos that were heat killed demonstrated significantly altered drop patterns (P < 0.001); first descending faster. In the second experiment, average descent times were different for embryos that stalled early versus those that developed to blastocyst (P < 0.001). Interestingly, more embryos dropped through the SGS developed to blastocyst than the culture control (P < 0.01).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

As this is a preliminary report of the SGS technology determining viability, a larger embryo population will be needed. Further, the current in vitro study will need to be followed by fecundity studies prior to application to a human population.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

If proven, the SGS would provide a noninvasive means of assessing embryos prior to transfer after assisted reproductive technologies procedures, thereby improving fecundity and allowing more reliable SET.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support of the U.S. Jersey Association, the Laura W. Bush Institute for Women's Health and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant through the Undergraduate Science Education Program to Texas Tech University. None of the authors have any conflict of interest regarding this work.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

none.

Keywords: embryo development, embryo selection, embryo viability, specific gravity, buoyance, noninvasive, zygote, blastocyst

Introduction

Even with the dramatic improvement in pregnancy rates from assisted reproductive technologies (ART) over the last 35 years, two issues remain problematic for patients and healthcare professionals using ART: (i) multiple gestations and (ii) the fecundity of individual embryos (Chandra et al., 2005; Center for Disease Control, 2013). To solve the first of these issues, ART now appears poised for yet another paradigm shift, the routine use of single embryo transfer (SET). However, in order to become the standard of care, a solution must be found to the second issue, individual embryo viability. Traditionally, embryo quality has been based solely on embryo morphology or embryo morphology coupled with expected growth rates (Gerris et al., 1999; Racowsky et al., 2010; Alfarawati et al., 2011a ,b; Machtinger and Racowsky, 2013). Yet, there remains significant disagreement among labs as to what constitutes a ‘normal embryo’ (American Association of Bioanalysts, 2013). Further, while the addition of PGD has improved the selection process, it is an invasive technique, which requires significant equipment and expertise, has an identified risk for embryo damage, and while it can diagnose genetic defects, it does not ensure the embryo will implant (Staessen et al., 2004; Brezina, 2013). Given the cost of the procedures, risks associated with medications and surgical procedures, and the emotional toll negative pregnancy results have on couples, any improvement in embryo selection, which is noninvasive, less subjective and leads to higher pregnancy rates, while limiting the risk of multiple gestations, would represent a significant improvement in women's reproductive health.

Recently this lab developed a technique which can estimate the weight of an embryo based on specific gravity. Preliminary data using the specific gravity system (SGS) suggested that cryopreserved cattle blastocysts from animals with known differences in body composition have significantly different estimated weights (Weathers, 2008). These differences appeared to be due to lipid content within the embryos. Further testing with fresh mouse embryos at various stages of preimplantation development (zygote to blastocyst), appeared to confirm this observation, both across a series of mouse strains with genetically different weights and within a single strain with animals of different weights (Weathers et al., 2013). However, in both of these studies, there were embryos with estimated weights significantly higher or lower than the mean established.

The overall goal of the present study was to determine if these observed differences in estimated weight within a cohort could be used to select high-quality embryos for ART procedures. In these initial studies, a series of experiments were conducted to determine if differences seen in estimated zygote weights could be used to (i) distinguish viable from nonviable embryos, (ii) predict future development and (iii) demonstrate that the technique did not negatively impact growth rates compared with a control population.

Materials and Methods

Development of the SGS and the measurement of embryo weight

In all experiments, descent time was measured and cultures were conducted in Ham's F-10 media (Irvine Scientific; Santa Ana, CA) plus 10% (v/v) Synthetic Serum Substitute (Irvine Scientific) as previously described (Weathers, 2008; Weathers et al., 2013). Initial studies used 0.5 ml straws (CryoBioSystem; Paris, France) completely filled with descent time medium and oriented vertically with the open end at the top. Embryos were placed at the meniscus at the top of the tube and allowed to descend in response to gravity while being observed through a dissection microscope (Nikon Instruments, Inc.; Melville, NY). The speed of descent was determined by the object's density and viscous drag, but when comparing objects of very similar shape and size, the speed of descent is directly related to weight. Therefore, embryo weight can be determined by comparing their descent time over a 1.0 cm distance to a standard curve derived from the descent time of beads with known weights of a similar size and shape to embryos (MO-SCI Specialty Products, L.L.C.; Rolla, MO).

However, while the above instrumentation worked in a research setting, between 10 and 20% of the embryos were lost during the weighing process, necessitating a design change to ensure embryo recovery in a clinical setting. The new system (Fig. 1) allowed the embryo to complete its descent into the central well of an organ culture dish (Falcon; Becton Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ). A small hole was made in the center of the lid of the dish so that a 0.5 ml cryo-straw with the cotton plug removed (chamber) could be inserted through the lid until it reached ∼2–3 mm above the bottom of the organ culture dish. The chamber was sealed in place with silicone adhesive and a pressure seal was added between the lid and base by stretching a thick rubber band that had been thinly coated with petroleum jelly around the bottom of the dish to form an air-tight seal. The device was then filled from the top with descent time medium first forming a pool in the center well of the organ culture dish and then continuing to fill until media reached the top of the straw forming a convex meniscus at the top of the straw. To estimate their weight, cumulus-free embryos were placed on the center of the meniscus with a stripper pipette (Orgio; Charlottesville, VA) under observation. Once the embryo reached the starting-line (2–5 mm from top of straw), its descent over a 1.0 cm distance was timed (seconds) and weights were calculated using the established mathematical formula for the standard curve described earlier (Weathers, 2008; Weathers et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

(A) The specific gravity system as designed for use (note lid has been removed from diagram for ease of visualization). The embryo is placed at the top of the open end of the weighing chamber and allowed to sink through the media. The embryo's rate of descent is measured as it passes through a 1 cm section labeled ‘timing zone.’ Once the timing is complete the embryo continues to descend into the middle section of a standard organ culture dish. (B) The lid can then be removed for easy embryo recovery and return to culture.

Verification of embryo recovery

Thirty-five 1-cell embryos were collected from four, 6–8 week-old wild-type CB6F1 mice (Charles Rivers; Burlington, MA) stimulated using standard protocols. In brief, mice were allowed to acclimatize after arrival before they were hyper-stimulated with 5 mIU FSH and 24 h later 5 mIU of hCG was administered to stimulate ovulation and the mice were mated to males of the same strain. Twenty-four hours after being mated, females were removed and weighed so that correlation between embryo weight and maternal weight could be investigated and embryos were retrieved. The harvested embryos were passed through the chamber to test recovery. After decent time was measured, the lid was carefully removed keeping the chamber aligned with the central well until all medium was drained. The volume of media in the chamber was too low to overflow the lower central well. Most embryos were automatically flushed into the lower central well. The few embryos that adhered to the wall of the descent chamber could be rinsed into the central well so that 100% of embryos ‘dropped’ through the system were recovered (see ‘Results’ section). They were transferred from the organ culture dish to a 24 well culture dish, with 0.5 ml of fresh media, for culture to determine if they would continue development for a minimum of two division cycles as determined microscopically.

Ability of the chamber to distinguish between live and dead 1-cell embryos

The destruction of the semi-permeable properties of the membranes surrounding a living cell would cause leakage of cellular components and in theory, a significant shift in cellular weight as water shifts into and out of the cells. Thus, the SGS should be able to discriminate between living and dead embryos based on changes in embryo's specific gravity after death. To test this hypothesis, 79 embryos were collected from a series of five hyper-stimulated mice. One embryo was discarded due to an abnormal shaped zona. The remaining embryos from each mouse were split equally between two treatments. The first group of embryos (controls; n = 39) were passed through the SGS chamber, their descent times were recorded, and they were then placed into standard culture (36.9°C, 5.8% CO2, balance room air), using fresh media similar to that used in SGS, for a period of 48 h. The second group (n = 39) were passed through the SGS to confirm consistency in descent times with the first group, but were then killed by placing their culture dish on a 60°C hot plate for 30 min. Once heat killed, these embryos were placed under the same culture conditions as the controls. All embryo descent rates were re-measured using the SGS after 24 and 48 h in culture, and controls were subsequently measured every 24 h until 120 h. The latter portion of the experiment was performed to determine if descent times changed as water and cellular contents diffused in and out of the embryo, as both cell numbers and embryo morphology changed over the 120 h time period.

To confirm the heat treatment disrupted membrane function in a pattern consistent with normal embryo death, a the heat method described earlier was compared with two other killing treatments; exposure to 3% formaldehyde—which would kill the cells but lock proteins in place by fixation and exposure to a pH of 6.8, the most likely of the three treatments to be encountered in routine culture. One hundred and eleven embryos were recovered from five mice and split between three treatments. All the embryos were dropped through the SGS to establish a baseline descent time. Embryos were then immersed in either 3% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, or in medium, which had been adjusted to an initial pH of 6.8 using hydrochloric acid, or exposed to a temperature of 60°C (as described earlier) all for a period of 30 min. The embryos were then returned to normal culture conditions for 48 h. After 24 and 48 h, the embryos were passed back through the SGS for descent rate estimations. A small percentage of the pH treated embryos experienced a single cell division at 24 h (5.4%), but no additional embryos had divided at 48 h. After all data were collected, descent times at 24 and 48 h were compared with those at the 0 h time point to establish if there were any changes in embryo specific gravity (and therefore descent time and weight) over the course of treatment.

Descent rate of 1-cell embryos versus future growth pattern

Twenty-seven mice were stimulated as above to create 1-cell embryos. Because maternal body composition can influence embryo weight (Weathers et al., 2013), no more than 20 embryos (10 for each experimental arm of the study) were used from any single mouse. Half the embryos (n = 207) were placed directly into culture, as described earlier, and assessed for development daily using cellular numbers and standard morphological evaluation. The remaining half (n = 207) were first dropped though the device and then placed into a 24-well culture plate as previously described. All embryos were cultured in individual wells to allow tracking of development and comparison to the initial descent time through the SGS. All embryos were then assessed for cellular development daily for a 4-day culture period. At the end of the culture period, embryos were ranked on a scale from 1 to 4 for final development (1 = remain 1 cell or died, 2 = multicellular, 3 = morula and 4 = blastocyst) to allow a comparison between initial descent time and final growth potential.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS ver. 12; Chicago, IL). The basic analysis was a two-way analysis of variance of treatment by time using a P-value of 0.05 for significance. In cases of significance by the original analysis, the differences within time or treatment were re-analyzed with either Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's mean separation as appropriate.

Results

Descent rate of heat-killed embryos

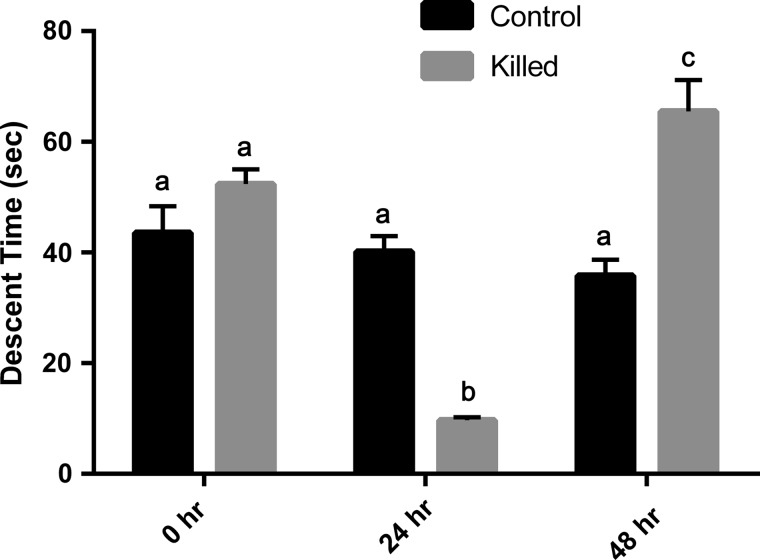

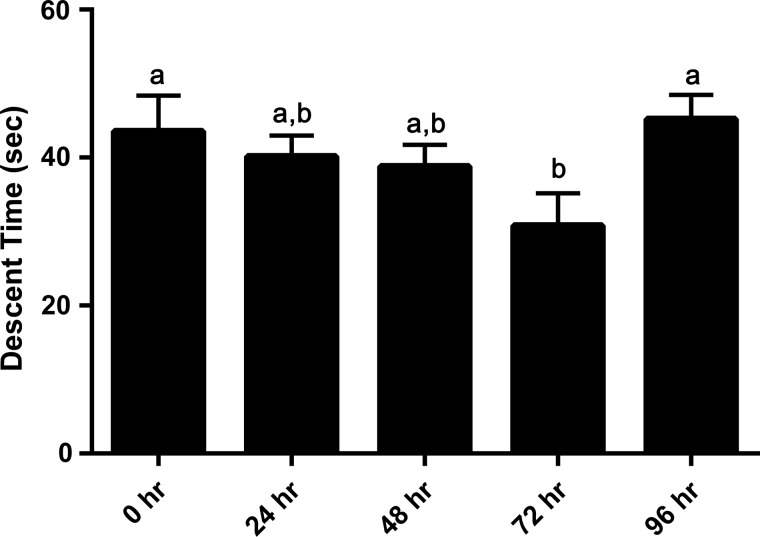

Heat-killed and control embryos demonstrated similar descent times (and therefore weights) at the 0 time point (Fig. 2). As expected, control embryos demonstrated increasing weights (decreasing descent time—measuring ∼4–12% daily) as they progressed from the 1-cell stage to the morula stage, and then a decrease (increased descent time) between 72 and 96 h as they developed a blastocoel cavity (Fig. 3; P < 0.02). Multiple exposures to the SGS over the 5-day period did not appear to adversely affect the embryo's growth potential. In contrast, the killed embryos demonstrated very different shifts in descent time over the 48 h period (Fig. 2; P < 0.001). They exhibited a large, highly statistically significant, decrease in descent time after 24 h to a value ∼25% of the control, and then a very large highly statistically significant increase after 48 h to a value ∼180% of the control.

Figure 2.

A comparison of mean descent time (SEM) of control (nonheat exposed) and heat-killed embryos through a modified specific gravity chamber at 24 h intervals over a 2-day period. While the control embryos demonstrated patterns similar to those reported in previous studies, heat-killed embryos exhibited drastically different patterns of descent, possibly due to changes in membrane integrity. Bars with different letters indicate a difference between measurement times (P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Mean descent time (SEM) of control (nonheat exposed) embryos over a 5-day period. Note changes in descent time appear to be affected by increases in embryo cell number as embryos continue to grow over time (time 0 h—1-cell stage, 96 h—blastocyst). Bars with different letters indicate a difference between measurement times (P < 0.02).

Comparison of killing methods

While there were significant differences in the way embryos responded 48 h after treatment, all killed embryo groups demonstrated faster descent rates during the initial 24 h, presumably due to an increase in inner-cellular water, increasing embryo density and weight (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A comparison of relative gain/loss of weight (measured as increases or decreases in descent time through a modified specific gravity system; mean ± SEM) by dead embryos killed using one of three methods: (i) heat (60°C), (ii) 3% formaldehyde fixation or (iii) a HCl-induced media pH drop to 6.8. Bars with different letters a–c represent differences with time, letters x–z represent differences within treatment (P < 0.001).

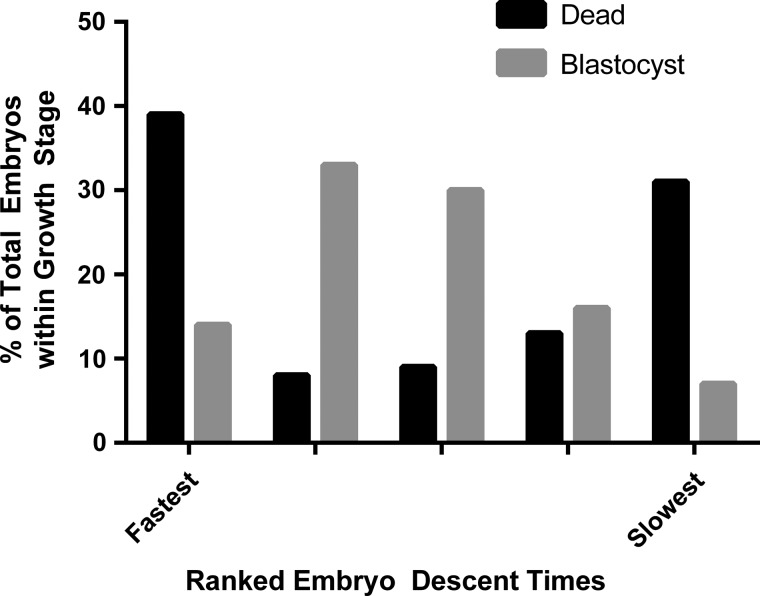

Descent rate of 1-cell embryos and their future growth pattern

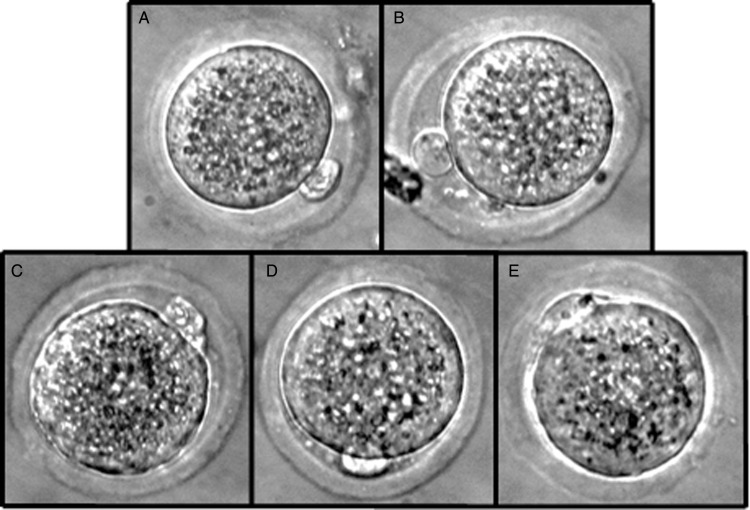

The descent times of the cohort of embryos from a single animal were normally distributed but the descent times for all 207 embryos formed a skewed curve (Fig. 5). This appeared to be due to the previously reported influence of the maternal donor (Weathers et al., 2013) as mean descent time for individual animal embryo cohort correlated with maternal weight at the time of embryo harvest (r2 = 0.721). Therefore, to allow a comparison between animals, all embryos from a single animal were ranked into quintiles from slowest (lightest weight) to fastest (heaviest weight) based on rates of descent through the SGS chamber. Sixty-five percent of the embryos developed to morula or blastocyst over the 4-day culture period, with 12% developing to a multi-cell stage (4–16 cells) and 13% remaining as one cell or dying. While there were embryos of all descent rate ranks represented in each stage of development, the majority of the embryos with the longest and shortest descent times were found to have died in culture. Further, comparing this group to the embryos, which developed to blastocyst suggested that while the embryos which developed to blastocyst demonstrated a similar skewed normal distribution to the population as a whole, the embryos that died in culture generated a U-shaped curve (Fig. 6; P < 0.001). These findings suggest that while the embryos were similar in appearance as zygotes (Fig. 7), there appear to be differences in their chemical constituents at this early stage, which will lead some to develop and others to stall or die.

Figure 5.

A comparison of the descent times of 207 1-cell embryos from 27 donor animals ‘dropped’ through a modified specific gravity chamber. While descent times ranged from 10 to 140 s, >70% of the embryos were clustered ±20 s of the population mean. The skewing toward faster descent times is possibly due to the influence of maternal body composition as reported in previous experiments.

Figure 6.

A relative weight comparison using a modified specific gravity chamber (faster descent time = heavier weight) of all embryos from 27 animals which either stalled or died at the 1-cell stage compared with those that reached the blastocyst stage after 4 days in culture. Embryos which developed to blastocyst tended to have descent times around the population median while those that stalled tended to have descent times at the extremes (P < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Micrograms of representative zygote stage embryos from a single embryo cohort used in comparing embryo estimated weight determined by a modified specific gravity system to the future growth and development potential of the embryos: (A) control—never exposed to chamber, (B) heat-killed embryos to induce loss of membrane function, (C) embryos with relative slow decent (light estimate weight), (D) embryos with a middle (most common) decent time (average weight) and (E) embryos with a fast descent time (heavy estimated weights).

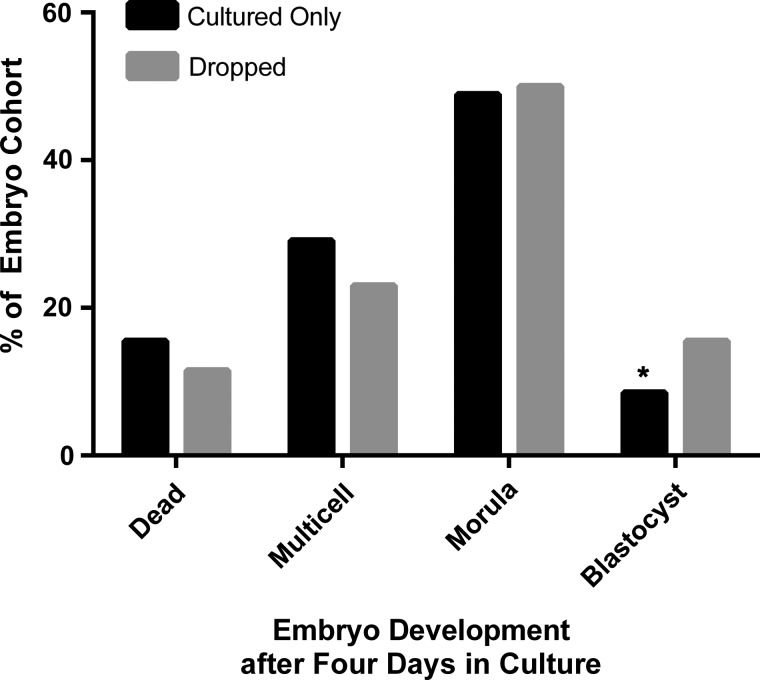

Finally, growth rates of embryos passed through the SGS were compared with growth rates of the embryos placed directly into culture. Both groups demonstrated >50% development to the morula and blastocyst stages after 4 days of culture. However, embryos passed through the SGS demonstrated greater development to blastocyst during the culture period (Fig. 8; P < 0.01).

Figure 8.

A comparison of the growth patterns of mouse embryos over a 4-day period for embryos which had been first passed through a specific gravity system (SGS) to estimate their zygotic weight (n = 207) versus those placed directly into culture (n = 207). Data suggest a higher rate of blastocyst development in embryos exposed to the specific gravity system (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Assisted reproductive technologies have made significant improvements over the last 30 years. Improvements in management protocols, culture technique and culture media have helped increase pregnancy rates while simultaneously decreasing the number of embryos transferred (Centers for Disease Control, 2013). The ultimate goal of all ART programs should be to move toward SETs, while maintaining high pregnancy rates. However, this requires the ability to select those embryos with the greatest potential for implantation and development. Traditionally, embryos have been selected solely on their morphologic appearance and normal rate of development. However, data from a recent Proficiency Testing Survey from the American Association of Bioanalysts suggest that there remains significant disagreement among labs as to what constitutes a ‘normal embryo.’ Fully one-quarter of the labs participating in the survey disagreed on the quality of embryos used in the evaluation (American Association of Bioanalysts, 2013).

The use of preimplantation genetic diagnosis/preimplantation genetic screening (PGD/PGS) has proved a significant step forward in in the selection process (McArthur et al., 2005; Grace et al., 2006; Alfarawati et al., 2011a,b; Scott et al., 2013). However, the procedure is invasive, not without risks, and can sometimes lead to erroneous results (Staessen et al., 2004; Brezina, 2013). It is also time consuming and requires a significant investment in equipment. Further, by the very nature of the test, it only tests the genetic fitness of the embryo, revealing little about the embryo's other physiological processes. Numerous groups have been searching for a noninvasive means of improving embryo selection, which would provide a complete picture of the embryo's ability to implant and develop (Gardner and Leese, 1987; Lane and Gardner, 1996; Jones et al., 2001; Houghton et al., 2002; Brison et al., 2004; Sakkas and Gardner, 2005; Conaghan et al., 2013; Gardner and Wale, 2013; Machtinger and Racowsky, 2013). However, to date, little progress has been made in finding an alternative to traditional morphology alone or morphology coupled with PGD/PGS.

While genetic composition is crucial to normal embryo development, it must be recognized that embryo development requires a number of factors, including an energy reserve and necessary chemical processes to survive from fertilization to implantation. The present research presents a novel, noninvasive technique potentially able to assess these factors, which can be applied at the earliest stage of development. The technique is based on the concepts that the shape and size of an oocyte and/or early embryo at the same stage of development is consistent and that all other parameters would be equal in an in vitro culture system. Therefore, any differences seen in embryo descent rate (density) should be the result of differences in internal embryo chemistry, which would be expected to influence embryo viability.

It was found that highly buoyant (long descent time) embryos fail to develop at a significantly higher rate compared with the rest of the cohort. Earlier work from this laboratory (Weathers, 2008) suggests that these differences are mainly due to a large incorporation of lipids into the embryo cytoplasm. Previous studies (Muñoz and Bongiorni-Malavé, 1979; Abe et al., 2002; Barcelo-Fimbres and Seidel, 2007; Chavez et al., 2012; Das and Holzer, 2012; Scott et al., 2013) have suggested that changes in the embryonic cytoplasm, as well as chromosomal anomalies account for most of the issues with embryonic growth. However, data from the viability studies with the SGS suggest that it might also be detecting differences in membrane integrity and the ability of individual cells to maintain osmoregulation as killed embryos demonstrate wide shifts in descent times over 48 h when compared with viable controls.

At this point, it is unclear if the SGS can detect chromosomal aneuploidy. However, it is clear that the system, which is easy to use, presents little to no risk to further development and, with the redesign, allows 100% recovery of embryos, and can detect the differences in growth potential at the earliest stages of development. While blastocyst development rates in the current study were lower than expected, possibly due to media selection, subsequent on-going studies with current human culture media (unpublished) have shown similar treatment effects with significantly higher rates of blastocyst development (>60% in all treatments); appearing to validate the earlier observations. When completed, these studies will have a significantly larger embryo cohort and expanded biochemical analysis. An unexpected finding from the study, which may merit future study, was the increased number of embryos that developed to blastocyst after being in the SGS versus the number that developed in the culture-only control. It is possible this observation, may be a fluke which will correct itself with additional numbers or may be a true finding due to a mild induced stress, or other factor resulting from exposure to the SGS; possibly even due to a brief exposure to a dynamic media environment during the embryo's descent. Further, while the number of blastocysts in this group was increased, it remains to be seen if they are competent to implant.

Advancement in all aspects of ART has improved the technique to the point where both researchers and law makers are calling for SET to become the norm (Janvier et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2013; Ercan et al., 2014). Because PGD/PGS, which is limited to detecting chromosomal abnormalities, and simple morphology, for which the usefulness in SET continues to be debated (Brezina, 2013; Machtinger and Racowsky, 2013; Scott et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013; Van den Abbeel et al., 2013), cannot ensure continued development of embryos post-transfer, there remains a need for improved selection criteria before mandating SET. The SGS, by itself, or in combination with other techniques, might represent a step forward in determining individual embryo fecundity and embryo selection for SET.

Authors’ roles

All three authors were significant contributors to the work and manuscript preparation on this project. S.D.P. developed the original concept and initial design of the SGS chamber. C.E.W. and L.L.P. refined the design prior to embryo testing. C.E.W. performed the majority of testing with embryos. While S.D.P. developed the original manuscript, all three were involved in editing for final content.

Funding

The authors would like to thank US Jersey, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Texas Tech University and the Laura W. Bush Institute for Women's Health for their financial support of this project. Funding met the guidelines the World Association of Medical Editors.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Abe H, Yamashita S, Satoh T, Hoshi H. Accumulation of cytoplasmic lipid droplets in bovine embryos and cryotolerance of embryos developed in different culture systems using serum-free or serum-containing media. Mol Reprod Dev 2002;61:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarawati S, Fragouli E, Colls P, Wells D. First births after preimplantation genetic diagnosis of structural chromosome abnormalities using comparative genomic hybridization and microarray analysis. Hum Reprod 2011a;26:1560–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarawati S, Fragouli E, Colls P, Stevens J, Gutiérrez-Mateo C, Schoolcraft WB, Katz-Jaffe MG, Wells D. The relationship between blastocyst morphology, chromosomal abnormality, and embryo gender. Fertil Steril 2011b;95:520–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Bioanalysts – Embryo Grading Proficiency Testing. http://www.aab-pts.org/pdf/stats/EmbAnds12013/AEF%20Embryo%20Grading%20Qualitative%201Q2013.pdf.

- Barcelo-Fimbres M, Seidel GE Jr. Effects of either glucose or fructose and metabolic regulators on bovine embryo development and lipid accumulation in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev 2007;74:1406–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezina PR. Preimplantation genetic testing in the 21st century: uncharted territory. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health 2013;7:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brison DR, Houghton FD, Falconer D, Roberts SA, Hawkhead J, Humpherson PG, Lieberman BA, Leese HJ. Identification of viable embryos in IVF by non-invasive measurement of amino acid turnover. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2319–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control – Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) http://www.cdc.gov/art/, 2013.

- Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Health Stat 23 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez SL, Loewke KE, Han J, Moussavi F, Colls P, Munne S, Behr B, Reijo Pera RA. Dynamic blastomere behaviour reflects human embryo ploidy by the four-cell stage. Nat Commun 2012;3:1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaghan J, Chen AA, Willman SP, Ivani K, Chenette PE, Boostanfar R, Baker VL, Adamson GD, Abusief ME, Gvakharia M et al. Improving embryo selection using a computer-automated time-lapse image analysis test plus day 3 morphology: results from a prospective multicenter trial. Fertil Steril 2013;100:412–9.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Holzer HE. Recurrent implantation failure: gamete and embryo factors. Fertil Steril 2012;97:1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan CM, Kerimoglu OS, Sakinci M, Korkmaz C, Duru NK, Ergun A. Pregnancy outcomes in a university hospital after legal requirement for single-embryo transfer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;175:163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Leese HJ. Assessment of embryo viability prior to transfer by the noninvasive measurement of glucose uptake. J Exp Zool 1987;242:103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Wale PL. Analysis of metabolism to select viable human embryos for transfer. Fertil Steril 2013;99:1062–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerris J, De Neubourg D, Mangelschots Van Royen E, Van de Meerssche M, Valkenburg M. Prevention of twin pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection based on strict embryo criteria: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Hum Reprod 1999;14:2581–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace J, El-Toukhy T, Scriven P, Ogilvie C, Pickering S, Lashwood A, Flinter F, Khalaf Y, Braude P. Three hundred and thirty cycles of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for serious genetic disease: clinical considerations affecting outcome. BJOG 2006;113:1393–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton FD, Hawkhead JA, Humpherson PG, Hogg JE, Balen AH, Rutherford AJ, Leese HJ. Non-invasive amino acid turnover predicts human embryo developmental capacity. Hum Reprod 2002;17:999–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier A, Spelke B, Barrington K. The epidemic of multiple gestations and neonatal intensive care unit use: the cost of irresponsibility. J Pediatr 2011;159:409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GM, Trounson A, Vella PJ, Thouas GA, Lolatgis N, Wood C. Glucose metabolism of human morula and blastocyst-stage embryos and its relationship to viability after transfer. RBM Online 2001;3:124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M, Gardner DK. Selection of viable mouse blastocysts prior to transfer using a metabolic criterion. Hum Reprod 1996;11:1975–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machtinger R, Racowsky C. Morphological systems of human embryo assessment and clinical evidence. Reprod Biomed Online 2013;3:210–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur SJ, Leigh D, Marshall JT, de Boer KA, Jansen RP. Pregnancies and live births after trophectoderm biopsy and preimplantation genetic testing of human blastocysts. Fertil Steril 2005;84:1628–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz G, Bongiorni-Malavé I. Influence of dietary protein restriction on ovulation, fertilization rates and pre-implantation embryonic development in mice. J Exp Zool 1979;210:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racowsky C, Vernon M, Mayer J, Ball GD, Behr B, Pomeroy KO, Ball GD, Behr B, Pomeroy KO, Wininger D et al. Standardization of grading embryo morphology. J Assist Reprod Genet 2010;27:437–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas D, Gardner DK. Noninvasive methods to assess embryo quality. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2005;17:283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RT Jr, Upham KM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Scott KL, Taylor D, Tao X, Treff NR. Blastocyst biopsy with comprehensive chromosome screening and fresh embryo transfer significantly increases in vitro fertilization implantation and delivery rates: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril 2013;100:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staessen C, Platteau P, Van Assche E, Miciels A, Tournaye H, Camus M, Devroey P, Liebaers I, van Steirteghem A. Comparison of blastocyst transfer with and without preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidy screening in couples with advanced maternal age: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2849–2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SM, Onwubalili N, Brown K, Jindal SK, McGovern PG. Blastocyst expansion score and trophectoderm morphology strongly predict successful clinical pregnancy and live birth following elective single embryo blastocyst transfer (eSET): a national study. J Assist Reprod Genet 2013;12:1577–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Abbeel E, Balaban B, Ziebe S, Lundin K, Cuesta MJ, Klein BM, Helmgaard L, Arce JC. Association between blastocyst morphology and outcome of single-blastocyst transfer. Reprod Biomed Online 2013;4:353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers J. Early Indications of Breed Differences for Cryopreservation of Embryos in Cattle. Master's Thesis, 2008 repositories.tdl.org/ttu-ir/bitstream/handle/2346/18883/Weathers_Julie_Thesis.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers N, Zimmerer N, Penrose L, Graves-Evenson K, Prien S. The relationship between maternal body fat and pre-implantation embryonic weight: Implications for survival and long-term development in an assisted reproductive environment. Open J Obst Gynecol 2013;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]