Abstract

Primary carcinoma of the parotid duct (Stensen’s duct carcinoma) is a rare entity, first described in 1927 and with approximately thirty-one cases reported in the English literature. Criteria for diagnosis are primarily demonstration of an origin from the Stensen’s duct lining and exclusion of parotid gland, accessory parotid, oral mucosal and adjacent minor salivary gland origin. The carcinoma is usually of a specific type, and most have been described as squamous, mucoepidermoid, or undifferentiated adenocarcinomas. We report an unusual case of Stensen’s duct carcinoma showing a primarily basaloid phenotype with focal squamous differentiation and a partial papillary architecture raising the possibility of malignant transformation in a ductal papilloma. Wide local excision was performed with postoperative radiotherapy and the patient is free of complications one and a half years postoperatively. Due to the small number of cases reported, the overall prognosis is not well defined, but seems to depend on the tumour size. Regional metastasis confers a 14 % mortality rate but there appears to be no relationship between histological type and prognosis.

Keywords: Salivary neoplasms, Intraductal papilloma, Stensen’s duct carcinoma

Introduction

Primary carcinoma arising in the excretory duct of the parotid gland (Stensen’s duct carcinoma-StDC) is a rare and poorly understood entity affecting mostly elderly patients and presenting as a mass lying superficially below the buccal mucosa or the deeper gland. The histological features described are diverse, with cases showing features of squamous, mucoepidermoid carcinoma or non-specific adenocarcinoma NOS. We report a case of a papillary squamous type, raising the possibility that it may have arisen through malignant transformation of a ductal papilloma of the parotid duct.

Case Report

A 76 year old female patient presented complaining of a painless swelling of the left parotid region. There were no obstructive symptoms. On extraoral examination, an erythematous area was noted in the right parotid duct region at the anterior of masseter muscle. Intraorally a solid mass was palpable at the orifice of the left parotid duct. The clinical suspicion was of a primary neoplasm of submucosal or subcutaneous tissues or an obstructive cause. Ultrasound revealed the dilated duct proximal to the mass, interpreted as a cystic component of a neoplasm, but an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration was inconclusive. MRI imaging favoured a primary salivary neoplasm in the duct that showed no extension to involve the parotid gland itself and dilatation of the proximal duct with secretion trapped behind the tumour (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. T1 weighted, left, showing a fusiform curved mass running along the line of the duct around the anterior border of masseter. T2 weighted, centre, showing a slightly heterogeneous tumour mass (T) in the distal duct extending from the parotid papilla to the anterior border of masseter muscle, with bright signal from secretion trapped behind the tumour in the very dilated proximal duct (S). T2 weighted image from the contralateral side, reversed, to show normal duct for comparison. P parotid gland, D duct, V blood vessel. The tumour showed patchy enhancement with gadolinium contrast (not shown)

A wide local excision was performed to remove a fusiform mass extending from the mucosal surface to the anterior border of masseter muscle. Longitudinal section of the mass revealed a solid and papillary mass filling the lumen of the parotid duct, which passed from one end of the specimen to the other. The periphery of the mass was well defined and smooth in outline, being the wall of the duct. Within this lay an unencapsulated epithelial neoplasm with a partly papillary outline and an organised epithelial surface layer, almost completely separate from the lining of the duct, which was largely intact (Fig. 2).

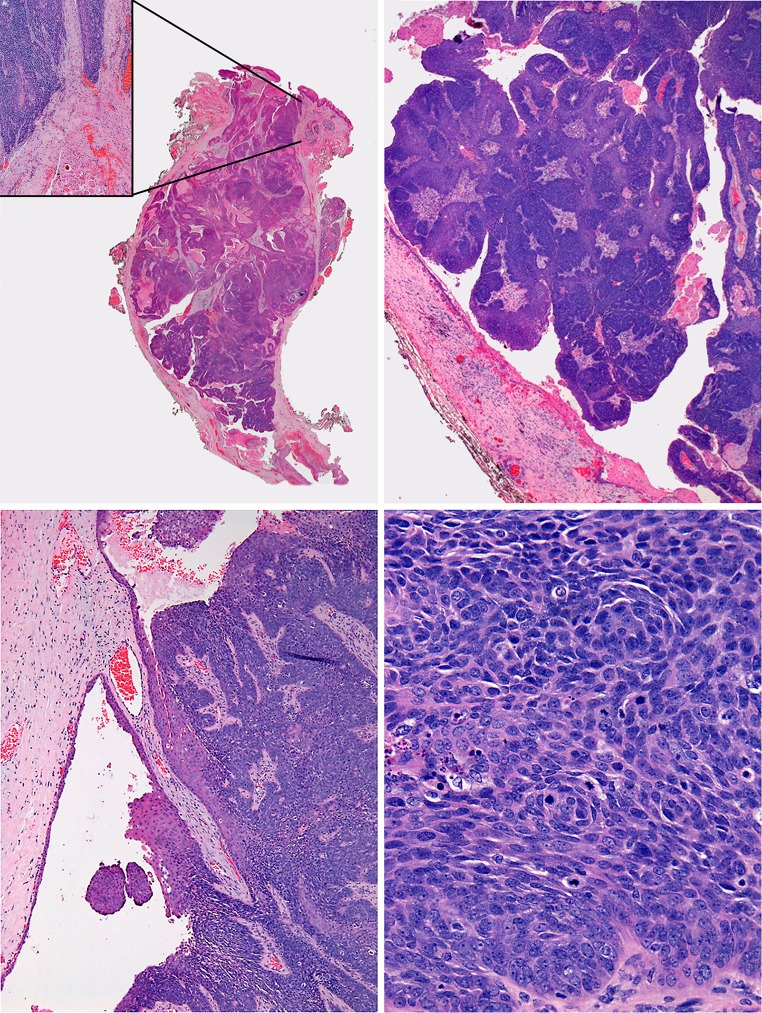

Fig. 2.

Top left, a low power view of the whole tumor showing a fusiform mass in the dilated duct, inset area of early invasion beyond duct impinging on muscle and vessels. Top right, prominent papillary architecture. Bottom left, tumor in continuity with surrounding duct lining epithelium. Bottom right, basaloid cells with frequent mitoses and apoptoses

Close to the parotid papilla there was extension through the wall with early infiltration of less than a millimetre into surrounding fibrous tissue in the superficial submucosa. Elsewhere the tumor was either retained within an intact duct or retained by the fibrous wall and did not infiltrate surrounding fat or muscle at any other site. At high power, the parotid duct lining epithelium was of normal thickness and without atypia and was seen to be continuous with the neoplasm. The main tumor mass was a carcinoma formed mostly by sheets of basaloid cells with a very few foci of prickle cell differentiation and minimal keratinization. Over half of the basaloid carcinoma had a strikingly papillary architecture peripherally. In more solid areas there were sheets and interconnected broad trabeculae of basaloid cells that showed focal comedo necrosis with abundant mitotic figures, apoptotic debris and obvious cytological atypia (Fig. 2).

No mucin was identified on ABPAS staining. The carcinoma cells were almost all strongly immunopositive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 and CK19 with focal positivity for CK7. Vimentin was negative. The few foci of lower prickle differentiation were at the periphery of the islands adjacent to the stroma, a feature of human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma, but p16 immunostaining and DNA in situ hybridisation for high risk HPV (Ventana Inform) were negative.

The diagnosis of Stensen’s duct carcinoma was made based on the intraductal location and histological and imaging exclusion of origin in minor salivary glands, buccal mucosa and parotid gland and clinical exclusion of metastasis.

The carcinoma did not fit well the histological criteria for any specific type of salivary neoplasm, but is close to a papillary squamous carcinoma of non-keratinising type. The only definite line of differentiation detected was squamous, indicated by focal clusters of prickle cells and CK5/6 expression, consistent with a papillary squamous carcinoma but also with the basaloid morphology and focal comedo necrosis raising the possibility of basaloid squamous carcinoma. However, basal cell adenocarcinoma of salivary origin is not such a high grade neoplasm. The striking papillary structure raises the possibility of malignant transformation in an inverted ductal papilloma and this architecture is not seen in the alternative differential diagnoses, but no definite precursor was identified.

The carcinoma was completely excised, but with a close margin of less than 1 mm. Postoperative external beam radiotherapy was performed in view of close margin and the patient received 6Mv photons to a dose of 50 Gy in 20 fractions. The patient is free of recurrence and other complications 18 months following excision.

Discussion

Primary neoplasms of the parotid duct are rare. Stensen’s duct carcinoma (StDC), carcinoma arising from parotid duct, and primary parotid duct carcinoma are all synonyms but the entity must not be confused with salivary duct carcinoma, a distinct high grade salivary neoplasm resembling mammary ductal carcinoma.

StDC is defined as a carcinoma that takes origin from the Stensen’s duct lining epithelium. Twenty-five potential cases have been claimed in the literature as Stensen’s duct carcinomas between the first published case in 1927 and 1999 (reviewed and compiled by Steiner [1] ). Including the present case, a further 6 cases have been documented since. However, some previously reported cases have been sarcomas or accessory parotid tumours and, when these are excluded, only 24 cases fit strict diagnostic criteria (Table 1). The ages of these patients ranged from 24–76 years with a mean age of 51 years and the male: female ratio was 2:1. This matches the mean age and sex recorded by Steiner in the review of 1999 [1].

Table 1.

Stensen’s duct carcinoma cases

| Ref. | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Goforth 1927 [1] | 60 | F | SCC | S + RT | Cervical metastasis, died after 1 year |

| 2 | Figi 1944 [1] | 62 | M | adenoCA | S + RT | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 3 | Lyall 1954 [1] | 40 | M | SCC | RT only | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 4 | Beyer 1956 [1] | 58 | F | adenoCA | S | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 5 | Pracchio 1958 [1] | 51 | F | SCC | RT only | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 6 | Maisel 1959 [1] | 53 | M | SCC | S | Recurred at 3 months |

| 7 | Gaisford 1965 [1] | 55 | F | MEC | S + ND | Rapid recurrence and death |

| 8 | Gaisford 1965 [1] | 25 | F | MEC | S + RT | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 9 | Gaisford 1965 [1] | n/a | M | MEC | S | Insufficient details provided |

| 10 | Clairmont 1979 [1, 12] | 53 | F | MEC | S (total) | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 11 | Clairmont 1979 [1, 12] | 48 | F | ACC | S (total) | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 12 | Owens 1982 [11] | 62 | M | SCC | S (superf) + RT | No recurrence or metastasis 18 months |

| 13 | Frechette 1984 [6] | 24 | M | Undif CA | S (superf) + RT | Not known |

| 14 | Carpenter 1986 [2] | 49 | M | ACC | S (superf) + RT | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 15 | Lari 1990 [1] | 58 | M | AdenoCA | Unknown | Unknown |

| 16 | Haar 1991 [1] | 57 | M | MEC | S | Recurred |

| 17 | Haar 1991 [1] | 57 | M | MEC | S (total) + RT | No recurrence or metastasis |

| 18 | Steiner 1999 [1] | 70 | M | SCC | S (WLE) | Insufficient details provided |

| 19 | Munoz-Guerra 2005 [7] | 38 | M | Undif CA | S (total) + ND | Local recurrence and death in 2 months |

| 20 | Giger 2005 [13] | 61 | M | MEC | S (superf) | No recurrence or metastasis after 3 years |

| 21 | Tominaga 2006 [5] | 67 | M | SCC | S | Recurred, died within 1 year |

| 22 | Kim 2009 [14] | 47 | M | SCC | S (total) + RT | No recurrence or metastasis at 31 months |

| 23 | Wakoh 2008 [3] | 62 | M | SCC | S | Insufficient details provided |

| 24 | Present case | 76 | F | See text | S | No recurrence or metastasis at 18 months |

Cases 1–18 are described in more detail in Steiner 1999 [1]

S surgery, RT radiotherapy, ND neck dissection, WLE wide local excision, CA carcinoma, SCC Squamous carcinoma, adenoCA adenocarcinoma NOS, MEC mucoepidermoid carcinoma, ACC adenoid cystic carcinoma, superf superficial parotidectomy, undif undifferentiated

Stensen’s duct has intra-parotid and extra-parotid segments and carcinomas can arise anywhere from the duct opening to the superficial lobe of the parotid gland [1] though just proximal to the orifice is the commonest site. When the site of origin is close to gland or accessory gland, a true intraductal origin may be difficult to ascertain [2]. Obstructive symptoms, as seen in this case on imaging (Fig. 1) may be helpful as they typically result from a StDC but not from accessory gland tumours [2]. Localisation by MRI and contrast enhanced CT imaging is also useful in this regard [3, 4].

It has long been hypothesized that excretory and intercalated ducts have stem cell or reserve cell populations that give rise to all normal and neoplastic salivary gland cells, though the experimental evidence for this is limited [5]. Excretory duct basal reserve cells are presumed to be the cell of origin of StDCs [6, 7], most of which appear to have squamous differentiation, though divergent differentiation can produce a range of patterns of carcinoma. Of the 24 currently accepted cases, 10 were squamous, 7 mucoepidermoid carcinomas, 3 unspecified types of adenocarcinoma, 2 adenoid cystic carcinomas and 2 undifferentiated carcinomas. Dysplasia of the duct lining epithelium would indicate definite ductal origin but has been present in only a few cases [1].

The present case had mixed squamous papillary and basaloid squamous histological features, its papillary architecture raising the possibility of malignant transformation of a ductal papilloma. Salivary duct papillomas can be of three types, inverted ductal papilloma, sialadenoma papilliferum, and intraductal papilloma. No features of inverted ductal papilloma or sialadenoma papilliferum were present. These two types arise almost always at the orifice of minor gland ducts, whereas intraductal papillomas arise in all ducts and can be more deeply placed [8]. While it is possible that this neoplasm either arose in an intraductal papilloma or is its malignant counterpart, this cannot be proven as no benign precursor was identified. However, the appearances are distinct from previously reported Stensen’s duct squamous carcinomas.

Malignant transformation of intraductal papilloma has been reported on only in two occasions in the English language literature. The resulting carcinomas were reported as intraductal papillary adenocarcinomas [9, 10] and arose in the intraparotid portion of Stensen’s duct and had a pure papillary architecture. Papillary features have not otherwise been described previously in Stensen’s duct carcinomas, so the present case is a closer fit to the features of accepted examples of intraductal papilloma with malignant transformation than other Stensen’s duct carcinomas.

Reported treatment for StDC has been primary surgery, the extent influenced by size [6] and histopathologic diagnosis [1]. Some have favoured complete duct excision including part of the superficial parotid gland [11] without prophylactic neck dissection [6]. The value of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is not defined but it may be considered to manage margin involvement [6].

Of the 24 acceptable cases to date only 22 have published follow up data (Table 1). Four patients died within 1 year, three due to local recurrence and one following cervical metastasis. Two developed local recurrences but further follow up details were not available. The patients who died had either squamous [2], mucoepidermoid or undifferentiated carcinoma. Two were treated by primary surgery, with neck dissections (one squamous and one mucoepidermoid) and one by radiotherapy alone (for squamous carcinoma). Numbers are too small to correlate survival with either treatment modality or histological type. It is clear that a relatively good prognosis can be expected in the absence of lymph node metastasis and cure would appear to be more likely when the carcinoma remains confined within the duct.

References

- 1.Steiner M, Gould AR, Miller RL, et al. Malignant tumors of Stensen’s duct. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:73–77. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter R, Watkins RM, Thomas JM. Primary carcinoma of Stensen’s duct. Br J Surg. 1986;73:926–927. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800731129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakoh M, Imoto K, Otonari-Yamamoto M, et al. Image interpretation for squamous cell carcinoma of Stensen duct. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e27–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tominaga Y, Uchino A, IShimaru J, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from Stensen’s duct. Radiat Med. 2006;24:639–642. doi: 10.1007/s11604-006-0078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dardick I, Burford-Mason AP. Current status of histogenetic and morphogenetic concepts of salivary gland tumorigenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:639–677. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frechette CN, Demetris AJ, Barnes EL, et al. Primary carcinoma of Stensen’s duct: recognition and management with literature review. J Surg Oncol. 1984;27:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930270102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munoz-Guerra M, Nieto S, Capote AL, et al. Undifferentiated carcinoma arising from the Stensen’s duct: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:415–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brannon RB, Sciubba JJ, Giulani M, et al. Ductal papillomas of salivary gland origin: a report of 19 cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:68–77. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.115978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiotani A, Kawaura M, Tanaka Y, et al. Papillary adenocarcinoma possibly arising from an intraductal papilloma of the parotid gland. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1994;56:112–115. doi: 10.1159/000276621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagao T, Sugano I, Matsuzaki O, et al. Intraductal papillary tumors of the major salivary glands. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:291–295. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0291-IPTOTM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owens OT, Fligiel AG, Ward PH. Primary carcinoma of Stensen’s duct. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1982;90:671–673. doi: 10.1177/019459988209000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clairmont AA, Hanna DC, Anderson VS. Carcinoma of Stensen’s duct. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;2:158–164. doi: 10.1097/00000637-197902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giger R, Mhawech P, Marchal F, et al. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of Stensen’s duct: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2005;27:829–833. doi: 10.1002/hed.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TB, Klein HZ, Glastonbury CM, et al. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of Stensen’s duct in a patient with HIV: the role of magnetic resonance imaging and fine-needle aspiration. Head Neck. 2009;31:278–282. doi: 10.1002/hed.20889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]