Abstract

Aetiology of stroke in young is often different to that of an older person. In nearly half of these cases no cause is established. Every effort should be explored to establish a cause as treatment varies accordingly and the prognosis with rehabilitation is favourable when compared with older people. We present a case of pontine infarct in a 43-year-old man due to vascular ectasia associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Following the stroke, the patient went through intensive rehabilitation where he had a good functional outcome.

Background

The cause of stroke in a young adult, between age group of 15 and45, is different from an older person. Nearly half the young strokes may not have a clear-cut established cause despite adequate investigations.

Their progress with rehabilitation is very good when compared with older people with strokes. Cerebral vascular anomalies like vascular ectasia (truncated vertebral artery) are an important cause of stroke.

The prevalence of cerebral arteriopathies in neurofibromas is 6%. They include vascular anomalies such as aneurysm, stenosis, arteriovenous malformations and vascular ectasia.

Full assessment for future stroke risk with vascular imaging may be necessary and is an important investigative tool in a young person with stroke.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old right-handed banker presented with loss of balance and dizziness. He initially experienced mild in-coordination affecting his right hand, which had rapidly resolved within a couple of hours. After 6 h he started experiencing vertigo and double vision when looking to the right. He was not on any medications, did not smoke and only took occasional alcohol. Interestingly, he had an established diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1 during his childhood. There was no family history of neurofibromatosis and stroke.

On examination he was found to have mild dysmetria involving his right arm. There was a right VI nerve palsy but other cranial nerves were normal. His gait was ataxic with normal and equal power in both lower limbs. All sensory modalities were preserved and his reflexes were intact and symmetrical. A clinical diagnosis of posterior circulation stroke syndrome was made probably involving the right pontomedullary area. On general examination he had visible cafe-au-lait spots and there were palpable neurofibroma in the lumbar region. There were two surgical scars where neurofibromas had been excised in his neck and over his right tibia.

Investigations

Initial investigations showed full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function test, coagulation screen, fasting glucose were within the normal reference range. The fasting lipids showed a value of 5.31 mmol/l for cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein level of 1.03 mmol/l, low-density lipoprotein level of 3.7 mmol/l and triglyceride level of 1.24 mmol/l. ECG showed sinus rhythm and chest x-ray showed no abnormality. CT of brain did not show any abnormality. He subsequently went on to have an MRI/MR angiography scan, which showed right pontine infarct (figures 1 and 2) and ectatic right vertebral artery (figure 3) which was truncated and larger than left vertebral artery at the level of foreman magnum1 and was occluded distally just before the insertion to basilar artery. There were no further vascular anomalies noted in other vascular territory. Echocardiogram with bubble contrast study showed normal ventricular function, chamber size and cardiac valves. There was also no evidence of patent foramen ovale. Vasculitic and thrombophilia screen were normal.

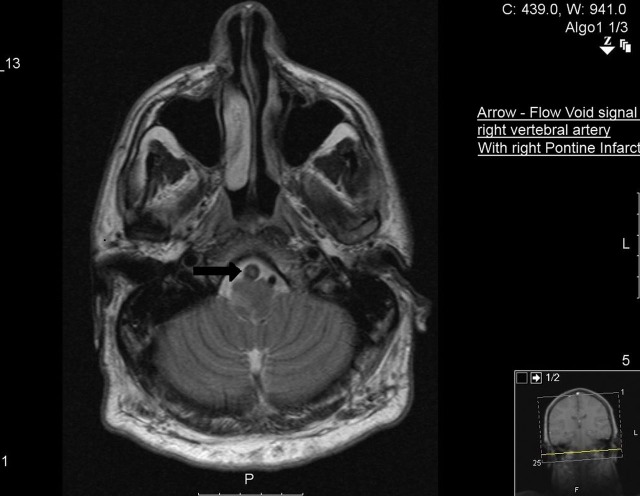

Figure 1.

MRI showing right vertebral artery with signal from intraluminal thrombus.

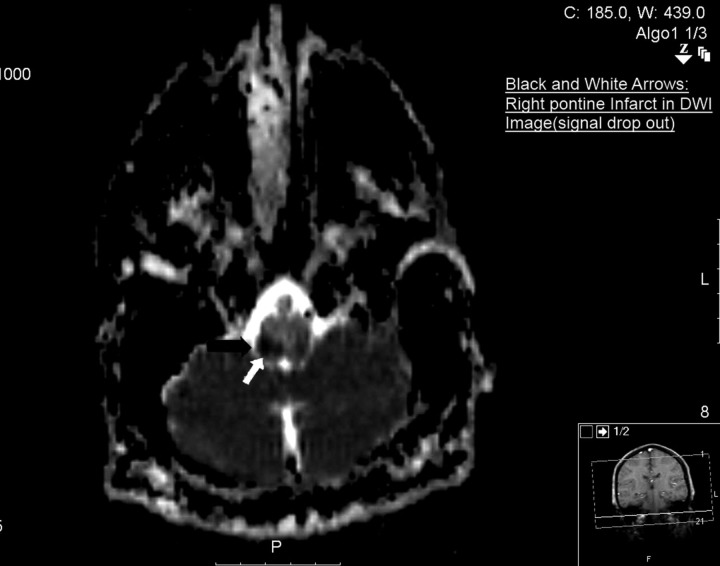

Figure 2.

MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging showing signal dropout in right pontine area suggesting acute infarct.

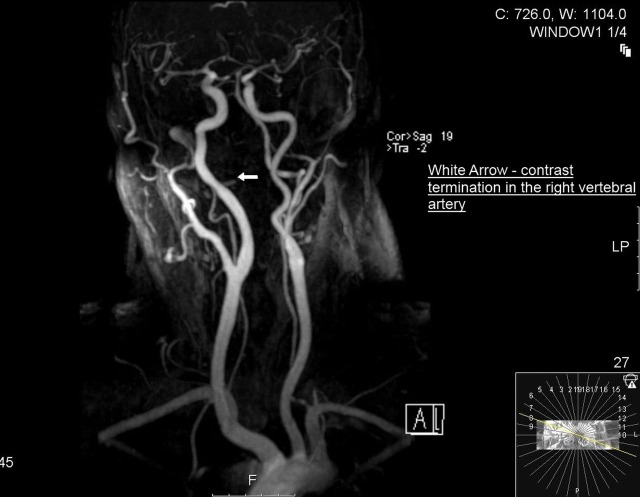

Figure 3.

MR angiography showing abrupt termination of distal right vertebral artery.

Treatment

He was treated with aspirin 300 mg initially for 14 days and dose reduced to aspirin 75 mg once a day with addition of dipyridamol moderate release preparation 200 mg twice a day for antiplatelet action. He was also started on simvastatin 40 mg once daily.

Outcome and follow-up

Further progress during rehabilitation was very good. His diplopia was corrected with a prism and his ataxic gait improved so that he was able to mobilise with minimal supervision after 2 weeks of rehabilitation. Our rehabilitation goal/target is for him to be functionally independent at home and work environment.

Discussion

The cause of stroke in a young adult, between age group of 15 and 45, is different from an older person, nearly half the young strokes may not have a clear-cut established cause despite adequate investigations.2 3 Potential for rehabilitation is generally very good in young when compared with older people with strokes.4 Cerebral vascular anomalies like vascular ectasia (truncated vertebral artery) are an important cause of stroke.1 5 The prevalence of cerebral arteriopathies in neurofibromas is 6%.6 7 They include vascular anomalies such as aneurysm, stenosis, arteriovenous malformations and vascular ectasia.1 3 6 These vascular anomalies are distributed in both anterior and posterior cerebral arterial territories.5 6 A hospital-based case series of follow-up of type 1 neurofibromatosis showed stroke as a neurological complication.8 There are also case reports of stroke in children9 and young adults10 11 as neurological sequel secondary vascular anomaly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.1 5 6 9–11 The exact mechanism for vascular anomalies is not known. It is believed that defective neurofibromin protein which is due to phenotypic expression of neurofibromatosis type 1 gene is responsible anomalous vascular smooth muscle formation. This results in aneurysmal, stenotic and vascular ecstatic changes in blood vessels.5 There appears to be no randomised controlled studies on the effective management of stroke secondary to vascular ectasia. Although a rare diagnosis and with an uncommon association, it is worthwhile doing a dermatological examination in younger patient with stroke to help establish a cause or association with neurofibromatosis.

Learning points.

The cause of stroke in a young person (age group 15–45) is not established well in nearly half the cases despite adequate investigations.

When a cause is found adequate investigations to establish the current risk and future risk for stroke should be well define and forms part of the treatment strategy.

Prognosis for rehabilitation in young person with stroke is favourable when compared with older people.

Neurofibromatosis should be considered in young individual with stroke as their phenotype expression is varied and can be easily missed during examination.

Up to 6% of cases with neurofibromatosis can have associated vascular anomalies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Martin PJ, Enevoldson TP, Humphrey PR. Causes of ischaemic stroke in the young. Postgrad Med J 1997;73:8–16. PMCID: PMC2431200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci 2000;27:120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oderich GS, Sullivan TM, Bower TC, et al. Vascular abnormalities in patients with neurofibromatosis syndrome type I: Clinical spectrum, management, and results. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosser TL, Vezina G, Packer RJ. Cerebrovascular abnormalities in a population of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 2005;64:553–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rea D, Brandsema JF, Armstrong D, et al. Cerebral Arteriopathy in Children With Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Pediatrics 2009;124:e476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Liu Y. Research update and recent developments in the management of scoliosis in neurofibromatosis type 1. Orthopedics 2010;33:335– 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohjasvaara T, Erkinjuntti T, Vataja R, et al. Comparison of Stroke Features and Disability in Daily Life in Patients With Ischemic Stroke Aged 55 to 70 and 71 to 85 years. Stroke 1997;28:729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Créange A. Neurological complications of neurofibromatosis type 1 in adulthood. Brain 1999;122:473–81. 10.1093/brain/122.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piovesan EJ, Scola RH, Werneck LC, et al. Neurofibromatosis, stroke and basilar impression. Case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1999;57:484–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang SC, Lee MJ, Jeng JS, et al. Novel mutation of neurofibromatosis type 1 in a patient with cerebral vasculopathy and fatal ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 2006;243:53–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rea D, Brandsema JF, Armstrong D, et al. Cerebral arteriopathy in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatrics 2009;124:e476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]