Abstract

Understanding the relationship between acid detergent lignin (ADL) and lodging resistance index (LRI) is essential for breeding new varieties of brown midrib (bmr) sudangrass (Sorghum sudanense (Piper) Stapf.). In this study, bmr-12 near isogenic lines and their wild-types obtained by back cross breeding were used to compare relevant forage yield and quality traits, and to analyze expression of the caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene using quantitative real time-PCR. The research showed that the mean ADL content of bmr-12 mutants (20.94 g kg−1) was significantly (P < 0.05) lower than measured in N-12 lines (43.45 g kg−1), whereas the LRI of bmr-12 mutants (0.29) was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than in N-12 lines (0.22). There was no significant correlation between the two indexes in bmr-12 materials (r = −0.44, P > 0.05). Sequence comparison of the COMT gene revealed two point mutations present in bmr-12 but not in the wild-type, the second mutation changed amino acid 129 of the protein from Gln (CAG) to a stop codon (UAG). The relative expression level of COMT gene was significantly reduced, which likely led to the decreased ADL content observed in the bmr-12 mutant.

Keywords: acid detergent lignin, brown midrib, dry matter, lodging resistance index, sudangrass

Introduction

Forage sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) is the most predominant forage crop in arid and semi-arid areas, largely because of its higher water use efficiency and stronger heat and drought tolerance (Cotton et al. 2012). It is also an important annual gramineae C4 crop that is widely used in the dairy industry, for fish farming, and for environmental conservation (Ledgerwood et al. 2009, Oliver et al. 2004, Xin et al. 2009). In recent years, extensive breeding and chemical approaches have led to great improvements in nutritive quality of forage sorghum (Marsalis et al. 2010), even some varieties now exhibit equal or higher milk production than silage maize (Zea mays L.) (Aydin et al. 1999, Bean and McCollum 2006). However, they typically have lower dry matter digestibility than forage corn, which have not been satisfactorily resolved at the harvest stage for silage or hay.

Lignin is one of the most abundant biopolymers in nature, with lignin secondary cell wall deposits being a major component of all vascular plants (Battle et al. 2000). Lignified secondary walls are beneficial to plants, providing mechanical and chemical support for water and nutrient transportation, and defending themselves effectively against biotic and abiotic stresses (Boerjan et al. 2003). Unfortunately, the complex linkages found in lignin decrease digestibility and dry matter intake by ruminants, thus affecting animal productivity (Allen 2000). Therefore, if the forage sorghum quality can be maintained at an acceptable level through lignin content reduction, then growers and dairies may be more willing to use the crop at a larger scale.

Recently, there has been a focus on improving the forage quality using the brown midrib (bmr) sorghum as it has significantly reduced indigestible lignin content and increased forage digestibility in comparison to other sorghum varieties, at levels close to forage maize (Aydin et al. 1999, Saballos et al. 2008). However, it is reported that bmr genes have negative impacts on agronomic performance, and are associated with reduced yield and increased lodging. Oliver et al. (2005) reported that, over a three-year study, the average yield of bmr near isogenic lines was 12% less than non-brown midrib hybrids. Zuber et al. (1977) reported a higher incidence of stalk breakage at maturity in bmr plants. Meanwhile, there was a 17–26% decrease in crushing strength in three bmr hybrids compared with normal lines (Miller et al. 1983). Subsequent research indicated the negative agricultural fitness associated with bmr mutations could be ameliorated through plant breeding (Sattler et al. 2010). Bean et al. (2013) observed no significant differences in lodging between bmr and conventional forage sorghum, this was possibly dependent on the bmr gene interactions and the genetic background.

Most bmr sorghum studies have focused on feeding effect, nutritive value, allelic association, and molecular biology (Aydin et al. 1999, Saballos et al. 2008, Sattler et al. 2012), and only a few reports have revealed the relationships between lignin content and the lodging resistance index (LRI); even limited research has been performed using bmr sudangrass (Sorghum sudanense (Piper) Stapf). Although lignin biosynthesis genes associated with bmr-6 and bmr-12 sorghum have been isolated and analyzed (Bout and Vermerris 2003, Tsuruta et al. 2010), there are no related reports for bmr sudangrass.

In this study, bmr-12 near isogenic lines, and their wild-types, obtained by back-cross breeding of different sudangrass genetic backgrounds, were used as research materials to compare correlative traits of forage yield and quality, and analyze the expression level of the caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene in the lines investigated using quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The aim of this experiment is to reveal the relationship between lignin content and LRI in bmr-12 sudangrass. This study will facilitate the selection and usage of new bmr sudangrass varieties with low lignin content and high lodging resistance, thus providing large economic benefits for use as forage crop.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and treatments

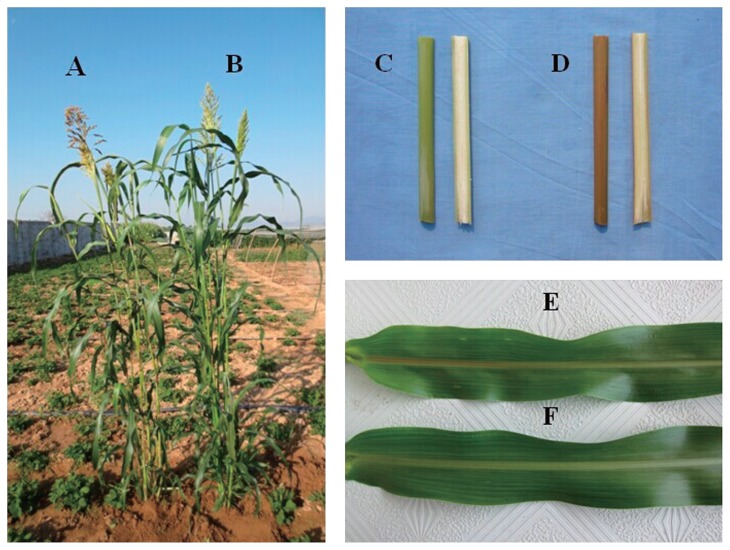

A pair of bmr-12 near isogenic lines (bmr-12 vs N-12) from F3 sudangrass populations was used in this study. The near-isogenic lines share similar characteristics for main stem growth period, plant height, leaf number, and stem diameter, but have differences in leaf midrib color (Fig. 1). They were purposefully screened and bagged from self-pollinated F1 and F2 descendants of a hybrid between S2006 (female parent, a green-midrib strain), and B4145 (male parent, a brown midrib-12 line). Their parents were derived from forage sorghum hybrids from China and the United States, and which obtained by six individual selections and three bulk selections, followed by two years of adaptability evaluation, from 2004 to 2011, respectively.

Fig. 1.

The bmr-12 (A) and N-12 plant materials (B) after 122 days of growth in southeast Hebei province. There were obvious differences in coloration of the stem and midribs of N-12 (C and F) and bmr-12 materials (D and E).

F3 seeds were dibbled to a depth of 3–5 cm in a plot of 30 m2 (6 m × 5 m) with row spacing of 50 cm × 20 cm, on May 29, 2013. The experiment was performed at the Dryland Farming and Water-saving Station of Hebei Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences (37°44′N and 115°42′E, elevation 20 m). The growing conditions at the experiment area are semi-arid, with a mean annual precipitation of 510 mm (70% in July and August), annual evaporation of 1785 mm, annual temperature of 12.6°C, a 206 day frost-free period, and the soil was silty loam. Within the top 20 cm of soil, organic matter was 12.2 g kg−1, alkali-hydrolyzable N was 67.2 mg kg−1, available P was 17.3 mg kg−1, and available K was 138 mg kg−1.

To measure differences between bmr-12 and N-12 plants in the F3 lines, 15 respective main stem samples with good growing away from the plot margins were measured to analyze yield traits at the filling stage (86 days after sowing). Meantime, samples for forage quality evaluation were collected and examined at the Silage Laboratory, Department of Grassland Science, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China. Samples obtained for investigation of gene expression were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until required for RNA isolation at the molecular laboratory of forage genetic resources, Institute of Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science, Beijing, China.

Trait analysis

Indicators of yield traits, including plant height (PH, length from base to tip of the spike), leaf number (LN, leaf number on the main stem after heading), stem diameter (SD, diameter of the main stem), fresh matter (FM, fresh matter of the main stem), dry matter per plant (DM, dry matter of the main stem after drying at 60°C), stem gravity (SG, height of the main stem gravity), snapping resistance (SR, at the 4th internode of the main stem), and LRI (Zhang et al. 2009) were measured at the Dryland Farming and Water-saving Station, Hebei Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, Hengshui, China. LRI was obtained using the following calculation: LRI = SR/(FW × SG). Photosynthetic indexes, including net photosynthetic rate (PN) and transpiration rate (TR), were measured using a CI-340 handheld photosynthesis system, and sugar content (SC) measured using a handheld Brix refractometer.

The crude protein content (CP) was determined using the Kjeldahl method (AOAC 1980). Amounts of neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), acid detergent lignin (ADL) and crude ash (CA) were determined using an ANKOM 2000 fiber analyzer according to Van Soest et al. (1991). The total digestible nutrients (TDN) content (Beck et al. 2013) was calculated using the equation TDN (%) = 105.2 – 0.6679 × NDF (%). The relative feed value (RFV) was obtained as follows:

Isolation of full-length COMT gene

Total RNA was isolated from the main stem using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Gene specific primers: P1 (5′-CACGAGAACACTTGCCAAGC-3′) and P2 (5′-CACCATGTATGGATCGGACAT-3′) were designed based on the COMT gene sequence of Sorghum bicolor (HQ668169), and used to amplify the COMT gene in S. sudanense. Touch down PCR reaction conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 10 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 65°C (ramping at −1°C per cycle) for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min; 20 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min; followed by an additional polymerization step at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified PCR fragment was cloned into a pMD18-T (Takara, Japan) vector following manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced.

Sequence and structural analysis

Sequence homology analysis was performed using BLAST tools (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Multiple alignments of deduced amino acid sequences were performed using DNAMAN Version 6.0. A search for open reading frames (ORF) and translation of nucleotide sequences was performed using the Open Reading Frame Finder at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method of MAGE5.0 software.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of COMT gene

Total RNA was isolated from the main stems using Trizol reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher, USA), and stored at −80°C. Primers P3 (5′-TAACGAGGACGGCGTCTCCA-3′) and P4 (5′-CGAGACGGACTCGTCGAAGC-3′) were designed to determine COMT gene expression levels in wild-type and mutant plants. The ACTIN gene was used as an internal control to normalize RNA quantity. The ACTIN primers used were P5 (5′-GGCAACATCGTCCTCTCTGG-3′) and P6 (5′-TCGGCTTGCATTTCTTGGGC-3′). Three biological replicates were performed for the quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data differences for each index between bmr-12 and N-12 materials were analyzed using a student’s t-test, and possible correlations between ADL content and LRI evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation. All statistical analysis was performed using version 18 of the SPSS software package (SPSS, Chicago, USA). SD were provided in all tables and figures as appropriate.

Results

Differences of phenotype and yield indexes between bmr-12 and N-12 plants

Although there were no obvious phenotypic differences between the two materials for leaf number after heading, spike type, spike shape, and tiller number of the main stem (Fig. 1), bmr-12 plants (Fig. 1D, 1E) exhibited a more intense reddish-brown coloration than N-12 materials at the midribs and stem (Fig. 1C, 1F), this useful trait was used as a phenotypic marker during the breeding and selection process. The bmr-12 plants produced a lower amount of fresh and dry matter, and had higher net photosynthetic rate (PN) than N-12 plants, but no significant (P > 0.05) differences were found in correlated yield indexes between the two materials, including PH, LN, SD, FM, DM, SR, PN, and TR (Table 1). However, the stem gravity (SG) of bmr-12 plants was significantly (P < 0.05) lower than that of N-12 counterparts, whereas the LRI of bmr-12 plants (0.29) was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than in N-12 plants (0.22).

Table 1.

Comparison of yield related traits in bmr-12 and N-12 plants

| Plant materials | PH‡ (cm) | LN | SD (mm) | FM (g) | DM (g) | SG (cm) | SR (g) | LRI§ | PN (μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) | TR (mmol m−2 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-12 | 236 ± 19 a† | 11 ± 1 a | 14.10 ± 2.11 a | 359 ± 51 a | 79.32 ± 11.42 a | 101 ± 6 a | 8143 ± 3055 a | 0.22 ± 0.05 b | 27.59 ± 3.05 a | 5.72 ± 0.61 a |

| bmr-12 | 233 ± 16 a | 11 ± 1 a | 14.08 ± 1.53 a | 330 ± 42 a | 76.61 ± 10.27 a | 95 ± 7 b | 9010 ± 2280 a | 0.29 ± 0.07 a | 28.27 ± 3.27 a | 5.27 ± 0.61 a |

PH, plant height; LN, leaf number; SD, stem diameter; FM, fresh matter per plant; DM, dry matter per plant; SG, stem gravity; SR, snapping resistance; LRI, lodging resistance index; PN, net photosynthetic rate; TR, transpiration rate.

The same letter indicates no significant differences between the two materials at P < 0.05.

Values are means ± SD (n = 15).

Comparison of nutritive value between bmr-12 and N-12 plants

There were no significant (P > 0.05) effects on SC, NDF, ADF, CP, TDN, CA, and RFV content between bmr-12 and N-12 plants harvested at the filling stage (Table 2). However, the mean ADL content in bmr-12 lines (20.94 g kg−1) was less than in N-12 lines (43.45 g kg−1, P < 0.05), thus the ADL content of bmr-12 plants was reduced by 51.8%. Meanwhile, Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed no significantly (P > 0.05) correlation between ADL content and LRI in bmr-12 and N-12 material, r = −0.44 and r = −0.21, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of quality related traits in bmr-12 and N-12 plants

| Plant materials | SC‡ (%) | CP (%) | NDF (g kg−1) | ADF (g kg−1) | TDN (%) | ADL§ (g kg−1) | CA (g kg−1) | RFV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-12 | 6.80 ± 1.57 a† | 9.94 ± 0.73 a | 501.63 ± 41.49 a | 306.68 ± 24.06 a | 71.61 ± 2.78 a | 43.45 ± 16.37 a | 14.21 ± 1.51 a | 121.43 ± 13.19 a |

| bmr-12 | 7.15 ± 1.35 a | 8.97 ± 1.14 a | 525.78 ± 15.74 a | 309.00 ± 9.75 a | 61.99 ± 1.05 a | 20.94 ± 1.30 b | 12.50 ± 1.23 a | 114.81 ± 4.73 a |

SC, sugar content; CP, crude protein; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; TDN, total digestible nutrients; ADL, acid detergent lignin; CA, crude ash; RFV, relative feed value.

The same letter indicates no significant differences between the two materials at P < 0.05.

Values are means ± SD (n = 15).

Structure and expression of COMT in the bmr-12 mutant

The use of RACE and RT-PCR technology enabled a 1424 bp full-length cDNA, containing a 1089 bp ORF encoding a protein of 362 amino acids, to be obtained. The molecular mass of the putative protein was ~39.6 kDa, and the pI ~5.6. It was named SsCOMT and deposited in GenBank (accession No. KJ101565).

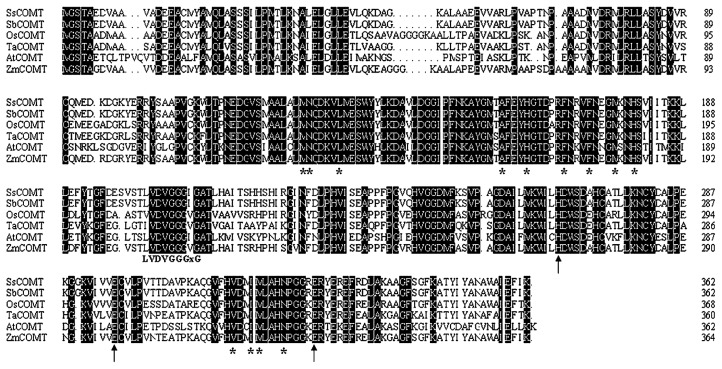

Sequence comparison with functionally characterized COMT proteins from various plants revealed high degrees of similarity, both at the nucleotide and amino acid level. The S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) binding domain LVDVGGGxG, a signature of O-methyltransferases, was conserved in SsCOMT. Catalytic residues and active site substrate binding residues were also conserved in SsCOMT (Fig. 2). The conserved binding domains and residues were all located at expected positions in SsCOMT.

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequences of SsCOMT, SbCOMT, OsCOMT, TaCOMT, AtCOMT, and ZmCOMT were initially aligned by DNAMAN6.0 using default parameters, and followed by manual alignment. Sequences used: SsCOMT (KJ101565), SbCOMT (AEM63601), OsCOMT (ABF72191), TaCOMT (AAP23942), AtCOMT (AAB96879), and ZmCOMT (AAQ24337). Dark shading represents 100% conservation. The S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) binding domain (LVDVGGGxG) was conserved in COMTs. Catalytic residues are marked by arrows, and active site substrate bind/positioning residues marked by asterisks. Numbers indicate the position from the start codon.

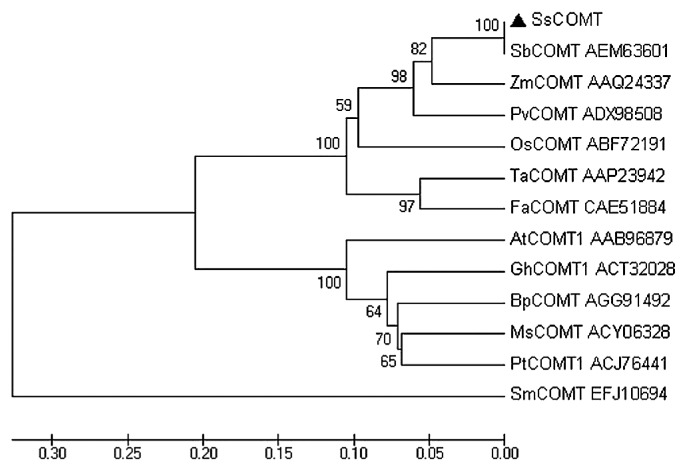

Based on the amino acid sequence, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by using neighbor-joining method. The result indicated that SsCOMT was homologous with monocotyledonous species. SsCOMT showed 100% amino acid sequence identity to SbCOMT, 89.89% to ZmCOMT, 80.5% to OsCOMT, 79.06% to TaCOMT, and 60.6% to AtCOMT (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree constructed using SsCOMT sequences and other COMT proteins. Thirteen-residue sequences were aligned and a phylogenetic tree constructed using the neighbor-joining method. Species used: S. sudanense (SsCOMT), S. bicolor (SbCOMT), Zea mays (ZmCOMT), Panicum virgatum (PvCOMT), Oryza sativa Japonica Group (OsCOMT), Triticum aestivum (TaCOMT), Festuca arundinacea (FaCOMT), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtCOMT1), Gossypium hirsutum (GhCOMT1), Betula platyphylla (BpCOMT), Medicago sativa (MsCOMT), Populus trichocarpa (PtCOMT1), and Selaginella moellendorffii (SmCOMT). GenBank accession numbers are indicated. The reliability of the tree was measured by bootstrap analysis.

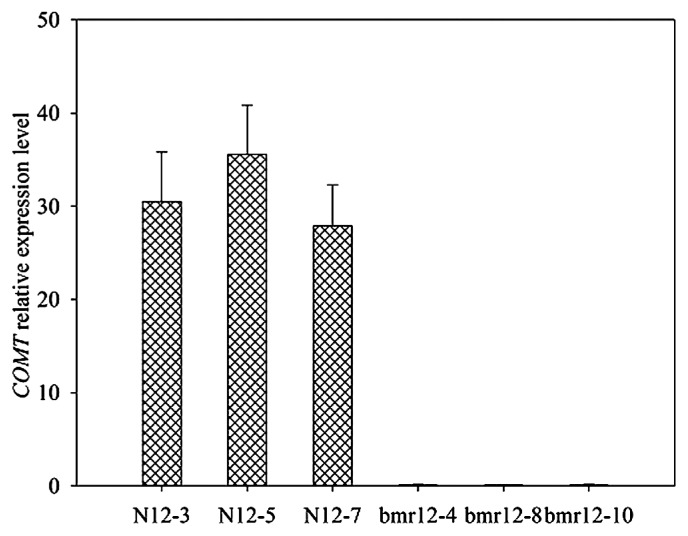

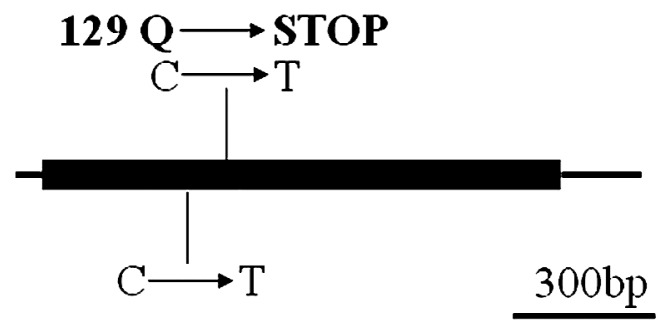

Alignment of the COMT sequences from bmr-12 and N-12 lines revealed single base-pair changes resulting in stop codons. The SsCOMT cDNA sequence analysis revealed two C to T transition mutations in the mutant but not present in the wild-type (Fig. 4). The first mutation did not change amino acid sequence, while the second changed the 129th amino acid of the protein from Gln (CAG) to a stop codon (UAG). Thus, the mutant was presumed a null allele. Meanwhile, the relative expression levels of the COMT gene between the two materials were analyzed by qRT-PCR and observed to be significantly reduced in bmr-12 compared with the N-12 lines (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram of wild-type and mutant COMT genes. CDS (coding sequences) are indicated as solid boxes and URT (Untranslated Regions) as lines.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of the COMT gene in bmr-12 and N-12 plants from F3 populations. Relative values of COMT gene expression in the 4th internode of the main stem, including bmr-12 and N-12 lines, are shown as a percentage of COMT expression activity. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Discussion

There was no significant (P > 0.05) variance in DM between the bmr-12 isogenic lines and N-12 plants, even though bmr-12 isogenic lines yielded 3.42% less DM than N-12 plants when harvested at the filling stage. This observed difference in dry matter is in contrast to most other observations in the literature. Beck et al. (2013) reported that when harvested at the booting stage of maturity, there was no difference in dry matter yield between bmr and non-bmr varieties (P > 0.05), and when harvested at the dough grain stage, the bmr variety produced 7500 kg more dry matter than the non-bmr variety (P < 0.01). Nevertheless, Oliver et al. (2005) reported there was no significant (P > 0.05) difference in different genetic backgrounds at the harvested hard dough stage. According to the above, it can be concluded that differences in dry matter yield of bmr and non-bmr materials may be due to differences in the harvesting stage. Therefore, it will be necessary to investigate regulational changes associated with dry matter accumulation at different growth periods in future studies.

The mean ADL content of bmr-12 lines (20.94 g kg−1) was significantly (P < 0.05) less than observed in N-12 lines (43.45 g kg−1), with a 51.8% reduction of ADL content. Similar findings were reported in previous studies, with the ADL content of bmr-12 lines being significantly less than in wild-type counterparts (Oliver et al. 2005, Saballos et al. 2008, Sattler et al. 2010). The lodging resistance index (0.29) associated with bmr-12 lines was higher than in the N-12 lines (0.22, P < 0.05), therefore the lodging resistance associated with bmr-12 plants could be significantly improved. Lodging is typically associated with inclusion of bmr genes (Miller et al. 1983, Zuber et al. 1977). However, Sattler et al. (2010) reported that increases in lodging attributable to brown midrib were not detected, and Bean et al. (2013) also reported no correlation between lodging and lignin content. Similarly, we observed no significant correlation between ADL content and LRI (r = −0.44, P > 0.05) in the bmr-12 near isogenic materials used in this work. The research indicated that other genetic characteristics are likely to play a significant role in the lodging resistance of bmr-12 plants, and lodging resistance associated with bmr-12 plants can be significantly improved by heterosis.

This study confirmed that bmr-12 plants had no significant effect on contents of CP, NDF, ADF, TDN, and RFV when harvested at the filling stage, and the results revealed that there was obvious gene × line interactions for the two materials in the same genetic backgrounds. Oliver et al. (2005) reported bmr genes had no effect on NDF content, and no differences in ADF content were observed in Kansas Collier or Rox Orange. Vogler et al. (2009) reported the bmr-12 mutant had higher NDF and ADF compared with its wild-type isoline in all tissues except for the panicle. Therefore, it is concluded that line and gene interactions made important contributions to the observed variations in fiber composition among bmr-12 sudangrass lines.

Lignin is a heterogeneous polymeric macromolecule that is a major component of the cell wall in vascular plants, it provides mechanical support for plant tissues and protects plants from pathogen invasion (Boerjan et al. 2003, Hammond-Kosack and Jones 1996). The COMT enzyme is a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, and has been targeted for manipulation of lignin content and composition through genetic engineering to improve forage digestibility, pulping efficiency, and use in in biofuel production (Louie et al. 2010). In forage sorghum, complex lignin linkages decrease digestibility and dry matter intake by ruminants, thus affecting animal productivity (Allen 2000). The COMT gene has been isolated and analyzed in bmr-12 sorghum, the bmr-12 mutant has a C to T transition at position 486 relative to the transcription start site, and expression of COMT mRNA is strongly reduced in bmr-12 mutants (Bout and Vermerris 2003). In this study, we isolated the cDNA sequence of the COMT gene and detected a point mutation, which resulted in a premature translation termination codon in the bmr-12 plant. The cDNA sequence analysis of SsCOMT indicated two C to T transition mutations were present in the mutant lines, but not in the wild-types. The first mutation did not change amino acid composition, however, the second mutation changed amino acid 129 from Gln (CAG) to a stop codon (UAG), and the relative expression level of the COMT gene was reduced significantly in bmr-12 mutants, and likely led to the reported lowering of ADL content in bmr-12 lines compared with the wild-types.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the earmarked fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System of China (CAR-35), and the Youth Foundation of Hebei Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences (A2012040101).

Literature Cited

- Allen, M.S. (2000) Effects of diet on short-term regulation of feed intake by lactating dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 83: 1598–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC (1980) Official Methods of Analysis, 13th ed Association of offical analytical chemists, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, G., Grant, R.J. and Rear, J.O. (1999) Brown midrib sorghum in diets for lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 82: 2127–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle, M., Bender, M.L., Tans, P.P., White, J.W.C., Ellis, J.T., Conway, T. and Francey, R.J. (2000) Global carbon sinks and their variability inferred from atmospheric O2 and delta 13C. Science 5462: 2467– 2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean, B. and McCollum, T. (2006) Summary of six years of forage sorghum variety trials. Texas Cooperative Extension and Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, College Station, TX, USA. Pub. SCS-2006-04. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, B.W., Baumhardt, R.L., McCollum, F.T. and McCuistion, K.C. (2013) Comparison of sorghum classes for grain and forage yield and forage nutritive value. Field Crops Res. 142: 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, P., Poe, K., Stewart, B., Capps, P. and Gray, H. (2013) Effect of brown midrib gene and maturity at harvest on forage yield and nutritive quality of sudangrass. Grassl. Sci. 59: 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan, W., Ralph, J. and Baucher, M. (2003) Lignin biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54: 519–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bout, S. and Vermerris, W. (2003) A candidate-gene approach to clone the sorghum Brown midrib gene encoding caffeic acid O-methyltransferase. Mol. Genet. Genomics 269: 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, J., Burow, G., Acosta-Martinez, V. and Moore-Kucera, J. (2012) Biomass and cellulosic ethanol production of forage sorghum under limited water conditions. Bioenerg. Res. 6: 711–718. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack, K.E. and Jones, J.D. (1996) Resistance gene dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell 8: 1773–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood, D.N., DePeters, E.J., Robinson, P.H., Taylor, S.J. and Heguy, J.M. (2009) Assessment of a brown midrib (BMR) mutant gene on the nutritive value of sudangrass using in vitro and in vivo techniques. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 150: 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, G.V., Bowman, M.E., Tu, Y., Mouradov, A., Spangenberg, G. and Noel, J.P. (2010) Structure-function analyses of a caffeic acid O-methyltransferase from perennial ryegrass reveal the molecular basis for substrate preference. Plant Cell 22: 4114–4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsalis, M.A., Angadi, S.V. and Contreras-Govea, F.E. (2010) Dry matter yield and nutritive value of corn, forage sorghum, and BMR forage sorghum at different plant populations and nitrogen rates. Field Crops Res. 116: 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.E., Geadelmann, J.L. and Marten, G.C. (1983) Effect of the brown midrib-allele on maize silage quality and yield. Crop Sci. 23: 493–496. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, A.L., Grant, R.J., Pedersen, J.F. and O’Rear, J. (2004) Comparison of brown midrib-6 and -18 forage sorghum with conventional sorghum and corn silage in diets of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87: 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, A.L., Pedersen, J.F., Grant, R.J. and Klopfenstein, T.J. (2005) Comparative effects of the sorghum bmr-6 and bmr-12 genes: I. Forage sorghum yield and quality. Crop Sci. 45: 2234–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Saballos, A., Vermerris, W., Rivera, L. and Ejeta, G. (2008) Allelic association, chemical characterization and saccharification properties of brown midrib mutants of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). Bioenerg. Res. 1: 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, S.E., Funnell-Harris, D.L. and Pedersen, J.F. (2010) Brown midrib mutations and their importance to the utilization of maize, sorghum, and pearl millet lignocellulosic tissues. Plant Sci. 178: 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, S.E., Palmer, N.A. and Saballos, A. (2012) Identification and characterization of four missense mutations in brown midrib 12 (bmr12), the caffeic O-methyltranferase (COMT) of sorghum. Bioenerg. Res. 5: 855–865. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta, S., Ebina, M., Kobayashi, M., Akashi, R. and Kawamura, O. (2010) Structure and expression profile of the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene and its association with lignification in the sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) bmr-6 mutant. Breed. Sci. 60: 314–323. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J., Robertson, J.B. and Lewis, B.A. (1991) Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74: 3583–3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, R.K., Tesso, T.T., Johnson, K.D. and Ejeta, G. (2009) The effect of allelic variation on forage quality of brown midrib sorghum mutants with reduced caffeic acid O-methyl transferase activity. Afr. J. Biochem. Res. 3: 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Z., Wang, M.L., Burow, G. and Burke, J. (2009) An induced sorghum mutant population suitable for bioenergy research. Bioenerg. Res. 2: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J., Li, H.J., Li, W.J., Xu, Z.J., Chen, W.F., Zhang, W.Z. and Wang, J.Y. (2009) The lodging resistance of erect panicle japonica rice in northern china. Sci. Agric. Sin. 42: 2305–2313. [Google Scholar]

- Zuber, M.S., Colbert, T.R. and Bauman, L.F. (1977) Effect of brown-midrib-3-mutant in maize (Zea mays L.) on stalk strength. Zeitschrift für Pflanzenzüchtung 79: 310–314. [Google Scholar]