Abstract

Rice tungro disease (RTD) is one of the destructive and prevalent diseases in the tropical region. RTD is caused by Rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV) and Rice tungro bacilliform virus. Cultivation of japonica rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp japonica) in tropical Asia has often been restricted because most japonica cultivars are sensitive to short photoperiod, which is characteristic of tropical conditions. Japonica1, a rice variety bred for tropical conditions, is photoperiod-insensitive, has a high yield potential, but is susceptible to RTD and has poor grain quality. To transfer RTD resistance into Japonica1, we made two backcrosses (BC) and 8 three-way crosses (3-WC) among Japonica1 and RTSV-resistant cultivars. Among 8,876 BC1F2 and 3-WCF2 plants, 342 were selected for photoperiod-insensitivity and good grain quality. Photoperiod-insensitive progenies were evaluated for RTSV resistance by a bioassay and marker-assisted selection (MAS), and 22 BC1F7 and 3-WCF7 lines were selected based on the results of an observational yield trial. The results demonstrated that conventional selection for photoperiod-insensitivity and MAS for RTSV resistance can greatly facilitate the development of japonica rice that is suitable for cultivation in tropical Asia.

Keywords: Rice tungro spherical virus, rice tungro disease, marker-assisted selection, photoperiod-insensitivity, japonica rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp japonica)

Introduction

Rice tungro disease (RTD) is one of the most destructive diseases of rice in tropical Asia (Hibino et al. 1991). Rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants affected by RTD show stunted growth, yellow to orange leaf discoloration, and few reproductive tillers (Thomas et al. 1980). RTD is caused by Rice tungro bacilliform virus (RTBV) and Rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV). Both RTSV and RTBV are transmitted by green leafhoppers (GLH) in a semi-persistent manner (Hibino et al. 1991). RTSV is independently transmitted by GLH, whereas RTBV can be transmitted by GLH only in the presence of RTSV (Hibino et al. 1990).

An evaluation of more than 40,000 rice germplasm accessions for RTSV and RTBV showed that dozens of traditional cultivars are resistant to RTSV, whereas only two cultivars are resistant to RTBV (Hibino et al. 1990, Shahjahan et al. 1990, Zenna et al. 2006). A genetic analysis of RTD-resistant rice cultivar Utri Merah showed that RTSV and RTBV resistance are independently inherited, and the interaction between both resistance traits is necessary to suppress RTD effectively (Encabo et al. 2009). RTSV resistance is a recessive trait controlled by the translation initiation factor 4 gamma (eIF4G) gene located between 22.05 and 22.25 Mb in chromosome 7 (Lee et al. 2010). The molecular marker, RM336 was successfully used for mapping the RTSV resistance gene (Lee et al. 2010). Sequence analysis of the eIF4G gene in cultivars resistant to RTSV identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in five combinatorial patterns that are associated with RTSV resistance (Lee et al. 2010).

The need for japonica rice (O. sativa L. ssp japonica) in Asia is increasing due to the increasing japonica rice consumers and trading (Magno and Yanagida 2000). Typical temperate japonica rice cultivars require a long-day photoperiod and are not adaptable to the short-day length conditions of the tropical regions. Photoperiod-sensitive japonica rice cultivars usually yield less than 1.2 ton/ha whereas photoperiod-insensitive japonica cultivars can yield up to 5.5 ton/ha in tropical regions (Philippine Rice Research Institute 2014). The rice variety Japonica1, which has been bred for tropical regions, has a high yield but is highly susceptible to RTD and has poor grain quality. Breeding of rice varieties for resistance to tungro viruses had relied exclusively on phenotypic selection. Here we report the application of marker-assisted selection (MAS) to transfer RTSV-resistance into photoperiod-insensitive japonica rice breeding lines to assure their stable yield in tropical environment. Numerous rice molecular markers linked to specific traits have been developed (Jena and Mackill 2008), but only a limited number of these molecular markers are actually being used for conventional rice breeding. This is the first case of molecular MAS for tungro virus disease resistance in the course of developing a japonica variety that is adaptable to tropical conditions.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Photoperiod-insensitive japonica varieties (Jinmi, Maligaya Special 11 (MS11) and Japonica1), photoperiod-sensitive varieties (Dongjin and Hwaseong) and an intermediately photoperiod-sensitive japonica variety (Sangju) were used in 10 cross combinations of backcrosses and three-way crosses (3-WC) (Table 1). Japonica1 has a high yield but has a poor grain quality and is susceptible to RTSV. Dongjin (Lee et al. 2010), Hwaseong, Sangju, Jinmi, and MS11 are resistant to RTSV. MS11 and Jinmi were included in the 3-WC as a source of good grain quality and photoperiod insensitivity. Jinmi, Dongjin, Hwaseong, Sangju, MS11, and Japonica1 have short and bold grains with an average of 1.8 length to width ratio and an average of 17–19% amylose content. Grains of these 6 varieties are clear and translucent with no significant chalkiness.

Table 1.

Selection for photoperiod-insensitivity and good grain quality at BC1F2 and 3-WCF2

| Cross combinations | No. of plants examined | No. of selected photoperiod-insensitive plants | No. of selected plants with good grain quality | Selection intensity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR97705 (Hwaseong/MS11)/Japonica1 | 225 | 17 | 9 | 4.0 |

| IR97707 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/MS11 | 101 | 12 | 7 | 6.9 |

| IR97708 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 1,025 | 124 | 64 | 6.2 |

| IR97709 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 1,000 | 119 | 71 | 7.1 |

| IR97711 (Dongjin/MS11)/Japonica1 | 750 | 37 | 25 | 3.3 |

| IR97715 (Dongjin/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 1,775 | 97 | 53 | 3.0 |

| IR97717 (Sangju/MS11)/Japonica1 | 1,000 | 19 | 18 | 1.8 |

| IR97719 (Sangju/Japonica1)/MS11 | 1,300 | 56 | 26 | 2.0 |

| IR97720 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 700 | 21 | 14 | 2.0 |

| IR97721 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 1,000 | 91 | 55 | 5.5 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 8,876 | 593 | 342 | 3.9 |

MAS for RTSV resistance

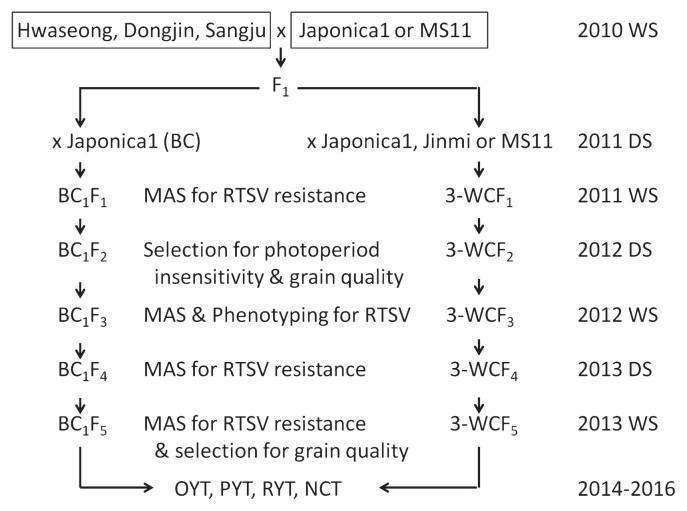

MAS for RTSV resistance was carried out for F1, F3, F4, and F5 generations (Fig. 1). The F2 generations were excluded from MAS for RTSV resistance because of the selection of the F2 generations for photoperiod insensitivity. Genomic DNA samples were prepared from the young leaves of plants using the modified TPS method (Miura et al. 2009). The tips of rice leaves (5 cm) were excised and ground in TPS buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 M KCl, 10 mM EDTA) using a GenoGrinder (OPS Diagnostics). After centrifugation, the supernatant was recovered and an equal volume of isopropyl alcohol was added. The isopropyl alcohol-insoluble material was recovered by centrifugation, and the pellet was rinsed with 75% ethanol. The pellet was then dried and dissolved in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, RNase A [10 mg/ml]). The DNA samples were then used for genotyping using the simple sequence repeat marker, rice microsatellite 336 (RM336, McCouch et al. 2002, forward primer: CTTACAGAGAAACGGCATCG, reverse: GCTGGTTTGTTTCAGGTTCG, 21.87 Mb of chromosome 7, according to IRGSP 1.0 of the rice annotation project database at http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/) that is tightly linked to the RTSV resistance gene (Lee et al. 2010). The PCR profile was as follows: pre-denaturation for 5 min at 95°C, 35 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 95°C—annealing for 30 sec at 55°C—extension for 30 sec at 72°C, and final extension for 7 min at 72°C. The PCR products were resolved on TAE (Tris-Acetate-EDTA) agarose gel (3%) for 1 h at 250 volts.

Fig. 1.

Breeding scheme for the development of Rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV)-resistant photoperiod-insensitive rice via selection for RTSV resistance and grain quality. RTSV-resistant varieties, Dongjin, Hwaseong, and Sangju were crossed with Japonica1 to produce F1. MS11 and Jinmi were used as the donor for photoperiod insensitivity. DS) dry season, WS) wet season, OYT) observatory yield trial, PYT) preliminary yield trial, RYT) replication yield trial.

Background selection for photoperiod insensitivity and grain quality

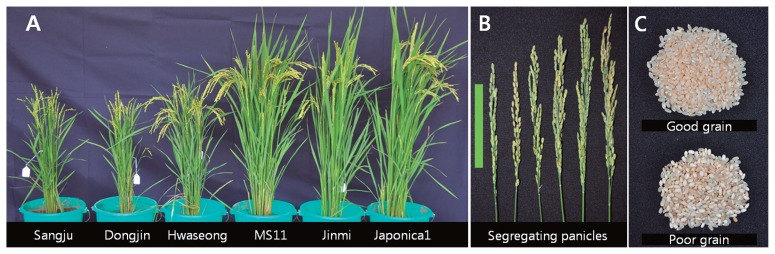

The photoperiod-sensitive japonica rice varieties typically exhibit early flowering and poor vegetative growth when grown under tropical conditions (12–14 hour day length; 25–33°C average day temperature). In the tropical condition of Philippines, the average height of highly photoperiod-sensitive japonica varieties is about 55 cm; they flower earlier than 45 days after seeding (Fig. 2A); and their panicles are shorter than 15 cm (Fig. 2B). Stricter criteria were applied for background selection of the BC1F2 and 3-WCF2 generations for photoperiod insensitivity. Plants that were taller than 75 cm; had panicles longer than 22 cm; and that flowered at or after 60 days after seeding were considered photoperiod-insensitive. The selection criteria for good grain quality include grain chalkiness, opacity, color, boldness and appearance (Webb et al. 1985). The grains were dehulled and examined by visual test. Plants with grains that are not chalky, clear translucent, bold (length/width ratio less than 1.9), and short (shorter than 5.5 mm in length) were selected (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic selection criteria for photoperiod insensitivity and grain quality. (a) Difference in height among photoperiod-sensitive varieties (Sangju, Dongjin and Hwaseong) and photoperiod-insensitive varieties (MS11, Jinmi and Japonica1). (b) Typical segregation of panicle length and grain number in BC1F2 plants. Panicles from BC1F2 plants of IR97705. Scale bar equals 10 cm. (c) Typical segregation in grain chalkiness and opacity in BC1F2 plants. Grains from BC1F2 plants of IR97705.

Evaluation for reaction to RTSV

RTSV strain A (Cabauatan et al. 1995) was used as the source of inoculum. The GLH-mediated inoculation of plants with RTSV was carried out using the modified water tray method as described by Azzam et al. (1999). BC1F2 and 3-WCF2 plants from the respective cross combinations that had been selected for good grain quality and photoperiod insensitivity were advanced to BC1F3 and 3-WCF3. Twenty BC1F3 and 3-WCF3 plants per line were grown in seed boxes. At 10 days after germination, the seedlings were placed inside a water tray and covered with a screen cage. RTSV-viruliferous GLH that had been allowed to feed on RTSV-infected plants for 4 days were released into the cage at an average of seven GLH per seedling for 3 hours to effect RTSV transmission. After inoculation, the trays were filled with water until the test seedlings were submerged to remove the GLH. One month after inoculation, leaves were collected from each plant and RTSV infection in the seedlings was examined by a double-antibody sandwich-enzyme- linked immunosorbent assay (Bajet et al. 1985). The presence of RTSV in the leaf extracts was determined by measuring the absorbance of the leaf extracts at 405 nm (Cabunagan et al. 1993). Plants whose 10-fold-diluted leaf extracts exhibited an absorbance value greater than 0.1 were considered to be infected with RTSV. F3 lines with an infection rate of <20% were classified as resistant, those with 21 to 79% infection as segregating, and those with >80% infection as susceptible (Lee et al. 2010).

Results

Hybridization between photoperiod-insensitive and RTSV-resistant varieties

F1 plants were obtained by crossing the photoperiod-insensitive varieties Japonica1 or MS11 with three RTSV-resistant varieties Hwaseong, Sangju, or Dongjin (Fig. 1). The F1 plants from two crosses (Hwaseong/Japonica1 and Sangju/Japonica1) were backcrossed to Japonica1, and the F1 plants from the other six crosses (Hwaseong/Japonica1, Hwaseong/MS11, Dongjin/Japonica1, Dongjin/MS11, Sangju/Japonica1, and Sangju/MS11) were used for 3-WC with Japonica1, Jinmi, or MS11 to produce 10 different cross combinations (Fig. 1, Table 1). Among the 236 BC1F1 and 3-WCF1 plants, 110 were identified to have a homozygous RTSV resistance allele, 22 have a homozygous susceptible allele, and 104 have heterozygous RTSV resistance/susceptible alleles by MAS using RM336. All the 110 BC1F1 and 3-WCF1 plants with homozygous resistance alleles were advanced to the next generation. Also, 25 of the 104 heterozygous BC1F1 and 3-WCF1 plants that are over 70 cm tall, with panicles that are 20 cm long and that had wide, deep green and erect leaves were advanced to the next generation.

Selection of BC1F2 and 3-WCF2 for photoperiod insensitivity and grain quality

The F2 progenies derived from the 10 cross combinations segregated for plant height, panicle length, vegetative growth period, and flowering date. Among the 8,876 BC1F2 and 3-WCF2 plants generated from the 10 cross combinations, 593 plants were selected as photoperiod-insensitive (Table 1). F2 plants that were shorter than 75 cm in height were considered as photoperiod-sensitive and were discarded (Fig. 2A). The average panicle length of plants selected as photoperiod-insensitive was 22 cm. F2 plant panicles that were shorter than 22 cm, and flowered earlier than 60 days after seeding were considered photoperiod-sensitive and were discarded in the field (Fig. 2B). A total of 593 photoperiod-insensitive F2 plants were harvested and dehulled for grain quality test. Grains that were chalky, opaque, or irregularly-shaped were discarded (Fig. 2C). A total of 342 BC1F2 and 3-WCF2 plants were selected for photoperiod insensitivity and good grain quality and were advanced to BC1F3 and 3-WCF3 (Table 1). Only 3.9% of the F2 plants were selected and advanced to the next generation indicating that photoperiod sensitivity resulting in short plant height, early flowering and short panicle length, as well as poor grain quality, is highly heritable in tropical regions.

Evaluation of BC1F3 and 3-WCF3 by RTSV bioassay

Among the 342 BC1F3 and 3-WCF3 lines, 324 were examined for their reaction to RTSV (18 lines of IR97717 were excluded from phenotyping for RTSV infection). Among the 324 lines examined, 209 were classified as resistant to RTSV, 44 as segregating for RTSV resistance, and 71 as susceptible to RTSV. From the 209 resistant lines and 44 segregating lines, a total of 154 plants were selected. Three panicles were harvested from each of the 154 plants, and a total of 462 plants were advanced to the next generations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phenotypic selection for RTSV resistance at BC1F3 and 3-WCF3

| Cross combinations | No. of lines examined | No. of resistant lines | No. of segregating lines | No. of susceptible lines | No. of lines selecteda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR97705 (Hwaseong/MS11)/Japonica1 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| IR97707 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/MS11 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| IR97708 Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 64 | 22 | 23 | 19 | 39 |

| IR97709 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 71 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| IR97711 (Dongjin/MS11)/Japonica1 | 25 | 16 | 9 | 0 | 13 |

| IR97715 (Dongjin/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 53 | 33 | 1 | 19 | 26 |

| IR97717 (Sangju/MS11)/Japonica1b | 18 | – | – | – | 7 |

| IR97719 (Sangju/Japonica1)/MS11 | 26 | 7 | 2 | 17 | 9 |

| IR97720 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 5 |

| IR97721 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 55 | 50 | 2 | 3 | 18 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 342 | 209 | 44 | 71 | 154 |

Three panicles were harvested from each line selected.

Penotyping for RTSV infection was not conducted for IR97717, and the selection was made on the basis of field performance.

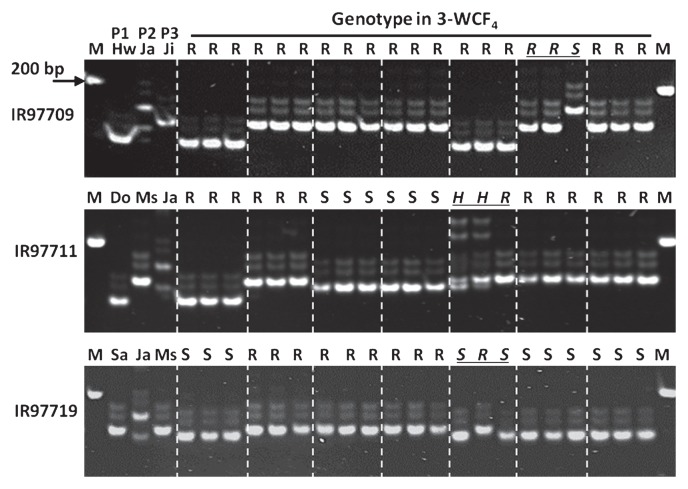

MAS of BC1F4 and 3-WCF4 for RTSV resistance

A total of 462 BC1F4 and 3-WCF4 lines were planted in the field. Among the 462 lines, 78 lines were selected for MAS based on field performance. Three plants from each of the 78 lines were subjected to genotyping for RTSV resistance using RM336 (Fig. 3, Table 3). Among the 78 lines, all plants of 50 lines were found to have homozygous RTSV resistance alleles, whereas 11 lines segregated into resistant, susceptible, or heterozygous genotypes (underlined italic genotypes in Fig. 3, Table 3). It appeared that the locus linked to RM336 is heterozygous in Japonica1, and that only either of the two alleles in Japnoica1 was passed on to some progenies (genotypes indicated as ‘S’ in Fig. 3). In case of IR97709, no segregating or susceptible lines were found among the previous 71 lines of 3-WCF3 examined for phenotypes for RTSV infection (Table 2); however, the genotype data showed segregation in the 3-WCF4 generation of IR97709 (underlined italic genotypes in Fig. 3), suggesting that the contradictory results may be due to missed inoculation of RTSV via GLH on some 3-WCF3 plants of IR97709 that might have occurred during the phenotyping of the 3-WCF3 lines. Three panicles were harvested from each of the 60 BC1F4 and 3-WCF4 lines that have homozygous or heterozygous RTSV resistance alleles (Table 3), and a total of 180 lines were advanced to the next generation (Table 4). Another MAS for RTSV resistance for 180 BC1F5 and 3-WCF5 lines identified 62 lines to be homozygous for RTSV resistance alleles. The grains of 62 lines were dehulled and evaluated by visual examination. Forty-two lines were selected for good grain quality (Table 4). Three panicles were taken from each of the 42 lines and consequently a total of 126 lines were advanced to the next generation for observatory yield trial (OYT). Based on yield performance and agronomic traits in the OYT, we finally selected 22 lines (Table 5). The 22 lines selected showed a yield higher compared to MS11 and Japonica1 (Table 5).

Fig. 3.

Representative genotypes of 3-WCF4 plants using the SSR marker RM336 which is tightly linked to RTSV resistance. Japonica1 is susceptible whereas Hwaseong, Dongjin, Sangju, MS11, and Jinmi are resistant to RTSV. Three plants per line were examined for genotypes with RM336. Genotypes from different lines were separated by dashed lines. Underlined italic genotypes indicate segregation of genotypes in a line. M) marker, Hw) Hwaseong, Ja) Japonica1, Ji) Jinmi, Do) Dongjin, Ms) MS11, Sa) Sangju, R) resistant, S) susceptible, H) heterozygous.

Table 3.

Marker-assisted selection for RTSV resistance at BC1F4 and 3-WCF4 using RM336

| Cross combination | No. of lines planteda | No. of lines selected for genotyping | Genotypes | No. of lines selected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Resistant | Heterozygous | Susceptible | ||||

| IR97705 (Hwaseong/MS11)/Japonica 1 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| IR97707 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/MS11 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| IR97708 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 117 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 8 |

| IR97709 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 81 | 14 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| IR97711 (Dongjin/MS11)/Japonica1 | 39 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| IR97715 (Dongjin/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 78 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| IR97717 (Sangju/MS11)/Japonica1 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| IR97719 (Sangju/Japonica1)/MS11 | 27 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| IR97720 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 15 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| IR97721 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 54 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 462 | 78 | 50 | 11 | 17 | 60 |

Three panicles were harvested from each of the previous 154 BC1F3 and 3-WCF3 lines; therefore 462 BC1F4 and 3-WCF4 lines were planted. Of the 462 lines, 78 were selected for MAS for RTSV.

Table 4.

Marker-assisted selection for RTSV resistance at BC1F5 and 3-WCF5 using RM336

| Cross combination | No. of lines planteda | Genotypes | No. of lines selected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Resistant | Heterozygous | Susceptible | |||

| IR97705 (Hwaseong/MS11)/Japonica1 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| IR97707 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/MS11 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| IR97708 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 24 | 3 | 0 | 21 | 1 |

| IR97709 (Hwaseong/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 42 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| IR97711 (Dongjin/MS11)/Japonica1 | 15 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| IR97715 (Dongjin/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 18 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| IR97717 (Sangju/MS11)/Japonica1 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0b |

| IR97719 (Sangju/Japonica1)/MS11 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| IR97720 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Japonica1 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| IR97721 (Sangju/Japonica1)/Jinmi | 36 | 28 | 3 | 5 | 15 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 180 | 146 | 7 | 27 | 42 |

Three panicles were harvested from each of the previous 60 BC1F4 and 3-WCF4 lines; therefore 180 BC1F5 and 3-WCF5 lines were planted.

No IR97717 lines were selected due to bacterial blight infection.

Table 5.

Yield and agronomic characteristics of the 22 advanced breeding lines selected by observatory yield trial

| Designation | Heading date (Days after seeding)a | Culm length (cm)b | Panicle length (cm)b | Tiller numberb | Reproductive panicle numberb | Total plant mass (kg)a | Total grain weight (kg)a | Yield (kg)a | Yield (ton/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR 97705-8-1-1-1-2 | 83 | 75 | 19 | 12 | 10 | 3.61 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 4.73 |

| IR 97705-8-1-2-2-1 | 75 | 77 | 20 | 15 | 13 | 3.84 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 4.55 |

| IR 97708-15-1-3-3-1 | 77 | 71 | 18 | 12 | 11 | 3.53 | 1.01 | 0.79 | 4.89 |

| IR 97708-15-1-3-3-2 | 80 | 72 | 24 | 13 | 12 | 3.40 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 4.80 |

| IR 97708-23-1-1-1-3 | 75 | 64 | 20 | 11 | 10 | 3.53 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 4.79 |

| IR 97708-23-1-1-2-2 | 74 | 66 | 23 | 15 | 14 | 3.55 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 4.66 |

| IR 97709-30-1-3-3-1 | 77 | 69 | 19 | 16 | 16 | 4.11 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 5.07 |

| IR 97709-30-1-3-3-2 | 75 | 74 | 24 | 13 | 13 | 3.56 | 1.10 | 0.83 | 5.25 |

| IR 97709-30-1-3-3-3 | 77 | 71 | 22 | 11 | 11 | 3.26 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 4.73 |

| IR 97711-25-1-1-3-3 | 75 | 62 | 19 | 12 | 11 | 3.26 | 0.96 | 0.73 | 4.52 |

| IR 97711-25-1-3-1-2 | 70 | 60 | 21 | 11 | 9 | 3.25 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 4.50 |

| IR 97719-22-1-3-3-3 | 74 | 77 | 24 | 16 | 16 | 3.62 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 4.51 |

| IR 97721-29-1-3-3-2 | 72 | 72 | 21 | 16 | 16 | 4.19 | 1.19 | 0.74 | 4.59 |

| IR 97721-29-1-3-3-3 | 75 | 76 | 22 | 15 | 14 | 4.36 | 1.01 | 0.77 | 4.77 |

| IR 97721-38-3-2-1-1 | 74 | 77 | 24 | 17 | 17 | 4.40 | 1.01 | 0.75 | 4.63 |

| IR 97721-38-3-2-1-2 | 74 | 72 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 3.98 | 1.04 | 0.76 | 4.73 |

| IR 97721-38-3-2-1-3 | 65 | 66 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 3.98 | 1.01 | 0.75 | 4.67 |

| IR 97721-43-2-1-3-1 | 70 | 67 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 4.03 | 1.27 | 0.78 | 4.82 |

| IR 97721-43-2-1-3-2 | 70 | 65 | 20 | 16 | 14 | 4.16 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 4.74 |

| IR 97721-43-2-2-3-1 | 72 | 61 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 4.29 | 1.13 | 0.75 | 4.67 |

| IR 97721-43-2-2-3-3 | 77 | 70 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 4.73 | 1.36 | 0.93 | 5.78 |

| IR 97721-45-2-1-3-3 | 83 | 73 | 21 | 19 | 18 | 4.07 | 1.29 | 0.84 | 5.17 |

| Japonica1 | 79 | 71 | 20 | 12 | 11 | 3.28 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 3.50 |

| MS11 | 76 | 68 | 19 | 15 | 14 | 3.18 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 3.55 |

Average value among 30 plants.

Average value among 3 plants.

Discussiuon

RTSV and RTBV resistance traits in rice are independently inherited (Encabo et al. 2009). Both RTBV resistance and RTSV resistance may be necessary for the effective management of RTD in fields. However, MAS for RTSV resistance alone might have a significant impact on the management of RTD because RTBV cannot be transmitted by GLH without the helper virus RTSV. Moreover, RTSV enhances the damages caused by RTBV (Hibino et al. 1990). The DNA marker RM336 is tightly linked to the RTSV resistance gene (Lee et al. 2010). Therefore, transfer of RTSV resistance by MAS into varieties to be cultivated in RTD-prone areas is a practical approach toward RTD resistance breeding. Several virus species have been recognized to cause serious damages to rice production (Hibino 1996). Locations of resistance genes for rice viruses such as RTSV (Lee et al. 2010), Rice yellow mottle virus (Albar et al. 2003, Thiémélé et al. 2010), and Rice strip virus (RSV) (Hayano-Saito et al. 2000) have already been determined. MAS for resistance to RSV has been successfully implemented to breed RSV-resistant rice varieties (Chen et al. 2010).

Photoperiod sensitivity is a trait closely associated with flowering time. Rice is a facultative, short-day plant that requires certain periods of dark to flower (Ichitani et al. 1998, Yano et al. 2000). Photoperiod-sensitive japonica rice varieties in temperate regions are usually planted during periods of long day-length to ensure that plants achieve their full vegetative growth. Once subjected to short day-length (more than 14 hours of darkness), the plants start flowering (Vergara and Chang 1985). Cultivation of photoperiod-sensitive japonica rice varieties under the consistently short-day condition in tropical regions usually results in short vegetative growth, early flowering, short plant height, and short panicles that eventually lead to very low yield. Japonica rice cultivars such as Dongjin, Sangju and Hwaseong are photoperiod-sensitive and yield an average of 1.2 ton/ha at 40% grain filling ratio in tropical regions. The average number of filled grains/reproductive tiller of these varieties is about 25 grains (data not shown). On the other hand, photoperiod-insensitive cultivar Japonica1 yields an average of 5.5 ton/ha at 80% grain filling ratio, and at 150 grains/tiller. Therefore, selection of japonica cultivars for photoperiod insensitivity is important to improve the vegetative growth of the plants and to increase crop yield.

Photoperiod insensitivity is a complex and quantitative trait (Yano et al. 2000), thus multiple molecular markers might be required for MAS for the trait. Heading date 1 (Hd1) confers long vegetative growth (Yano et al. 2000) whereas Hd3a is closely associated with photoperiodic flowering time in rice (Zhang et al. 2012). The expression of Hd3a promotes flowering under short-day length conditions, and suppresses it under long-day length conditions (Tamaki et al. 2007). At least seven other genes (Hd1, Hd2, Hd4, Hd5, Hd6, Hd7, and Hd9) are also reported to be associated with vegetative growth and flowering time (Lin et al. 1998, 2002, Yamamoto et al. 1998, 2000, Yano and Sasaki 1997), suggesting that photoperiod sensitivity is a trait too complicated for MAS application. Despite of the genetic complexity associated with photoperiod insensitivity, the phenotypes resulting from photoperiod insensitivity distinctively segregated among the japonica rice populations examined in this study (Fig. 2A, 2B). Therefore, the evaluation for measurable phenotypes such as flowering date, plant height, and panicle length appears to be a more practical option than the use of genetic markers for selection for photoperiod insensitivity. The results of this study demonstrated that MAS for RTSV resistance can be adopted to facilitate breeding of RTSV-resistant, photoperiod-insensitive rice varieties for the stable production of rice in RTD-prone areas.

Literature Cited

- Albar, L., Ndjiondjop, M.-N., Esshak, Z., Berger, A., Pinel, A., Jones, M., Fargette, D. and Ghesquière, A. (2003) Fine genetic mapping of a gene required for Rice yellow mottle virus cell-to-cell movement. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107: 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam, O., Cabunagan, R.C. and Chancellor, T.C.B. (1999) Methods for the evaluation of resistance to rice tungro disease. IRRI Discussion Paper 38: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bajet, N.B., Daquioag, R.D. and Hibino, H. (1985) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to diagnose rice tungro. J. Plant Prot. Trop. 2: 1124–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Cabauatan, P.Q., Cabunagan, R.C. and Koganezawa, H. (1995) Biological variants of rice tungro viruses in the Philippines. Phytopathology 85: 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cabunagan, R.C., Flores, Z.M., Coloquio, E.C. and Koganezawa, H. (1993) Virus detection in varieties resistant/tolerant to tungro. Int. Rice Res. Notes 18: 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Zhang, S.Y., Zhu, W.Y., Zeng, S.Y., Yang, Y.C., Yuan, S.J. and Yang, L.Q. (2010) Improving resistance of japonica varieties Shengdao13 and Shengdao14 to rice stripe virus disease by molecular marker-assisted. Sci. Agric. Sinica 43: 3271–3279. [Google Scholar]

- Encabo, J.R., Cabauatan, P.Q., Cabunagan, R.C., Satoh, K., Lee, J.-H., Kwak, D.-Y., De Leon, T.B., Macalalad, R.J.A., Kondoh, H., Kikuchi, S.et al. (2009) Suppression of two tungro viruses in rice by separable traits originating from cultivar Utri Merah. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22: 1268–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano-Saito, Y., Saito, K., Nakamura, S., Kawasaki, S. and Iwasaki, M. (2000) Fine physical mapping of the rice stripe resistance gene locus, Stvb-i. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hibino, H., Daquioag, R.D., Mesina, E.M. and Aguiero, V.M. (1990) Resistances in rice to tungro-associated viruses. Plant Dis. 74: 923–926. [Google Scholar]

- Hibino, H., Ishikawa, K., Omura, T., Cabauatan, P.Q. and Koganezawa, H. (1991) Characterization of rice tungro bacilliform and rice tungro spherical viruses. Phytopathology 81: 1130–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Hibino, H.. (1996) Biology and epidemiology of rice viruses Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34: 249–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichitani, K., Okumoto, Y. and Tanisaka, T. (1998) Genetic analyses of low photoperiod sensitivity of rice cultivars from the northernmost regions of Japan. Plant Breed. 117: 543–547. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, K.K. and Mackill, D.J. (2008) Molecular markers and their use in marker-assisted selection in rice. Crop Sci. 48: 1266–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-H., Muhsin, M., Atienza, G.A., Kwak, D.-Y., Kim, S.-M., De Leon, T.B., Angeles, E.R., Coloquio, E., Kondoh, H., Satoh, K.et al. (2010) Single nucleotide polymorphisms in a gene for translation initiation factor (eIF4G) of rice (Oryza sativa) associated with resistance to Rice tungro spherical virus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23: 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H., Ashikari, M., Yamanouchi, U., Sasaki, T. and Yano, M. (2002) Identification and characterization of a quantitative trait locus, Hd9, controlling heading date in rice. Breed. Sci. 52: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.Y., Sasaki, T. and Yano, M. (1998) Mapping quantitative trait loci controlling seed dormancy and heading date in rice, Oryza sativa L., using backcross inbred lines. Theor. Appl. Genet. 96: 997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- McCouch, S.R., Teytelman, L., Xu, Y., Lobos, K.B., Clare, K., Walton, M., Fu, B., Maghirang, R., Li, Z., Xing, Y.et al. (2002) Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.). DNA Res. 9: 1999–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K., Agetsuma, M., Kitano, H., Yoshimura, A., Matsuoka, M., Jacobsen, S.E. and Ashikari, M. (2009) A metastable DWARF1 epigenetic mutant affecting plant stature in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 11218–11223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magno, R.C. and Yanagida, J.F. (2000) Effect of trade liberalization in the short-grain japonica rice market: A spatial-temporal equilibrium analysis. J. Philipp. Dev. 27: 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Philippine Rice Research Institute (2014) 60th Annual Meeting of the National Rice Cooperative Testing Project: 2013 Wet season trials, June 2–3 Philippine Rice Research Institute, Department of Agriculture, Philippines, pp. 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Shahjahan, M., Jalani, B.S., Zakri, A.H., Imbe, T. and Othman, O. (1990) Inheritance of tolerance to rice tungro bacilliform virus (RTBV) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 80: 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki, S., Matsuo, S., Wong, H.L., Yokoi, S. and Shimamoto, K. (2007) Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316: 1033–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiémélé, D., Boisnard, A., Ndjiondjop, M.-N., Chéron, S., Séré, Y., Aké, S., Ghesquière, A. and Albar, L. (2010) Identification of a second major resistance gene to Rice yellow mottle virus, RYMV2, in the African cultivated rice species, O. glaberrima. Theor. Appl. Genet. 121: 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J., Officer, P. and John, V.T. (1980) Suppression of symptoms of rice tungro virus disease by carbendazim. Plant Dis. 64: 402–403. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, B.S. and Chang, T.T. (1985) The flowering response of the rice plant to photoperiod, In 4th Ed, International Rice Research Institute, Manila, Philippines, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, B.D., Bollich, C.N., Carnahan, H.L., Kuenzel, K.A. and McKenzie, K.S. (1985) Utilization characteristics and qualities of United States rice. In: Rice grain quality and marketing, June 1–5, International Rice Research Institute, Manila, Philippines, pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Kuboki, Y., Lin, S.Y., Sasaki, T. and Yano, M. (1998) Fine mapping of quantitative trait loci Hd-1, Hd-2 and Hd-3, controlling heading date of rice, as single Mendelian factors. Theor. Appl. Genet. 97: 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Lin, H., Sasaki, T. and Yano, M. (2000) Identification of heading date quantitative trait locus Hd6 and characterization of its epistatic interactions with Hd2 in rice using advanced backcross progeny. Genetics 154: 885–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano, M. and Sasaki, T. (1997) Genetic and molecular dissection of quantitative traits in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 35: 145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano, M., Katayose, Y., Ashikari, M., Yamanouchi, U., Monna, L., Fuse, T., Baba, T., Yamamoto, K., Umehara, Y., Nagamura, Y.et al. (2000) Hd1, a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice, is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell 12: 2473–2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenna, N.S., Sta Cruz, F.C., Javier, E.L., Duka, I.A., Barrion, A.A. and Azzam, O. (2006) Genetic analysis of tolerance to rice tungro bacilliform virus in rice (Oryza sativa L.) through agroinoculation. J. Phytopathol. 154: 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.-H., Wang, K., Guo, L., Zhu, Y.-J., Fan, Y.-Y., Cheng, S.-H. and Zhuang, J.-Y. (2012) Pleiotropism of the photoperiod-insensitive allele of Hd1 on heading date, plant height and yield traits in rice. PLoS ONE 7: e52538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]