Abstract

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma is a rare type of cervical cancer that derives from mesonephric remnants in the uterine cervix. To the best of our knowledge, this is the 34th case of mesonephric adenocarcinoma in adult women documented in the literature. We present an asymptomatic 64-year-old postmenopausal woman presenting with a suspicious-looking cervix as an incidental finding and diagnosed with a stage IB mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix. This case was managed with radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingoophorectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. The rarity of such cases imposes challenges on the management in terms of diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic options.

Background

Mesonephric carcinomas are a distinct subtype of epithelial tumours of the uterine cervix which derive from the remnants of the paired mesonephric (Wolff's) ducts.1

Mesonephric remnants can be present in 22% of uterine cervices in adults.2

The incidence of such neoplasms is difficult to determine due to rarity, previous misclassification of clear cell carcinomas and yolk sac tumours as mesonephric carcinomas and potential underreporting due to misclassification of mesonephric carcinoma as mullerian tumours or mesonephric hyperplasia.3

The evidence regarding the clinical course, prognosis and optimal treatment is limited.

Case presentation

An asymptomatic 64-year-old patient was referred to colposcopy services, by her general practitioner with the indication of a suspicious-looking cervix during routine cervical smear. Her previous obstetric history included that of four vaginal births and the gynaecological that of menopause since the age of 50. Her medical history included hypothyroidism on thyroxin, asthma, osteoporosis and smoking. She also had a history of breast cancer treated with mastectomy and chemoradiation 8 years before.

Colposcopy gave the impression of invasive disease and directed cervical punch biopsies revealed closely packed dilated mucin-filled glands with an attenuated epithelial lining which was focally positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7). CK20, gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP), thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF1) and thyroglobulin were negative. These features were considered as consistent with a cervical mucinous lesion. No malignant features were evident but further evaluation was recommended. The cervical smear was normal.

The case was referred to the gynaecology multidisciplinary team and the suggestion was that of examination under anaesthesia, cystoscopy and cervical cone biopsy. The examination under anaesthesia and cystoscopy revealed an unusually indurated cervix.

The knife cone biopsy measures 22 × 13 and 18 mm in depth, and microscopically showed a diffusely infiltrating tumour composed of groups of dilated glands with minimal atypia. The tumour incompletely was excised and was present at one side of the cervical canal and measuring 20 × 9 × 7 mm. No lympho-vascular invasion was identified and the squamous epithelium and endocervical glands were normal.

Immunochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin (pan cytokeratine) AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), E cadherin and vimentin. CD10 was focally positive and with only occasional cells positive for calretinine. The tumour was negative for monoclonal carcino embryonic antigen (mCEA), CK20, TTF1, thyroglobulin and GCDFP (figures 1–3).

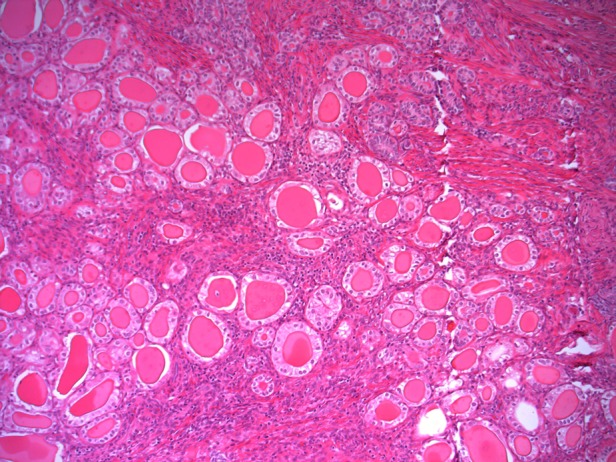

Figure 1.

Histology showed closely packed glands, lined by cuboidal epithelium with minimal to mild cytological atypia. Some glands are dilated and are filled with eosinophilic secretions. Mesonephric duct hyperplasia was seen elsewhere in the specimen (H&E).

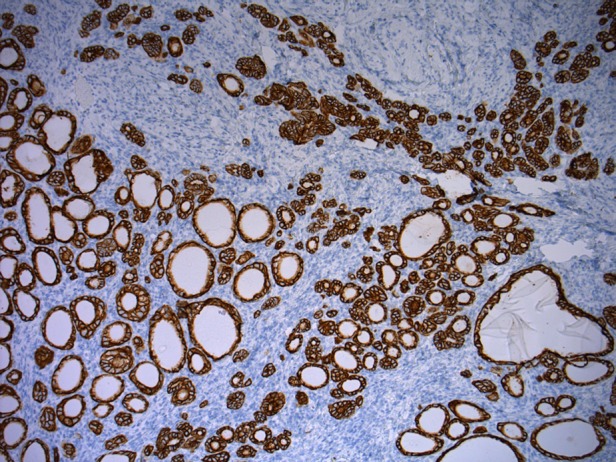

Figure 2.

Strong positivity for Pan-cytokeratin AE1/3 staining.

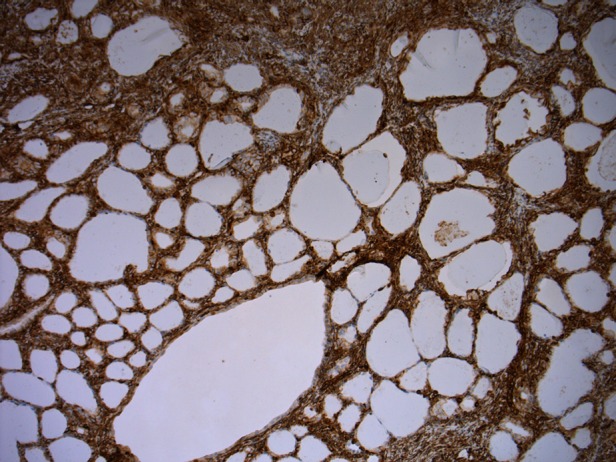

Figure 3.

Strong positivity for vimentin staining.

The features were considered to be suggestive of a well-differentiated mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix.

MRI was normal and the staging was that of T 1N0M0.

Radical hysterectomy specimen confirmed an International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) IB1 (with a maximum horizontal/depth tumour dimensions of 15/5 mm), well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with negative nodes (n = 19) and clear margins, with no lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI).

Staging with MRI scan took place before a radical hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingoophorectomy along with pelvis lymphadenectomy confirmed an IB1 well-differentiated mesonephric adenocarcinoma with negative pelvic nodes.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included the more common well-differentiated villoglandular adenocarcinoma of cervix, adenoma malignum, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear cell carcinoma and mesonephric hyperplasia.4

Treatment

This case was managed with radical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingoophorectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy.

Outcome and follow-up

Recovery from surgery was uneventful and the patient has remained disease-free for 6 months.

Discussion

The presenting symptom is most commonly abnormal uterine bleeding. Many cases are diagnosed as an incidental finding on cervical cone or hysterectomy specimen. Examination revealed a cervical mass in many of these cases.

Age range at presentation is between 24 and 73 years with a mean of 50.7.

Unlike the case of the more common squamous epithelial carcinoma, it is rarely presenting with the abnormal cervical smear result, has more advanced age at presentation and its incidence does not appear to decline with age.

The diagnosis has been supported by endometrial curettings, directed/cone cervical biopsies and hysterectomy specimens.

A common finding on endometrial biopsies is endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

The microscopic appearance can be characterised by the predominant pattern. More common patterns are the tubular, which needs to be distinguished from diffuse mesonephric hyperplasia, and the ductal pattern, which needs to be distinguished from endometrioid adenocarcinomas of cervix and its minimal deviation variant. Malignant spindle cell biphasic pattern (malignant mixed mesonephric tumour, MMMT) should be differentiated from primary MMMT of cervix. Focal retiform and sex-cord-like patterns are more common in adnexal tumours deriving from remnants of upper Wolffian duct.5

These neoplasms tend to be adjacent to areas of mesonephric glandular hyperplasia.6

Mesonephric remnant hyperplasia, even with deep infiltrating and diffuse hyperplastic appearance, is not related to poor prognosis and needs to be distinguished from malignant lesions.7 Discriminating features of adenocarcinoma are nuclear atypia, increased mitotic activity (>10/HPFs) (high power field), lymphovascular space invasion and necrotic luminal debris. Ki immunostain may also prove useful in differentiating.3

Immunochemical features of mesonephric adenocarcinoma include positivity for CK7, CAM5.2, EMA and reactivity for CD10, calretinine and vimentin. Carcino embryonic antigen (CEA), CK20, ER and PR are usually negative.7 As expected, immunoreactivity for p16 is negative, thus not linking these tumours with high-risk human papillomavirus infection.8 Immunoreactivity for PAX2 seems to be absent in mesonephric adenocarcinoma and cervical adenocarcinoma along with its minimal deviation variant, but is diffusely positive in mesonephric hyperplasia.9

Owing to the small number of cases with adequate follow-up, prognosis cannot be accurately predicted. The vast majority of patients with cervical adenocarcinoma of mesonephric origin diagnosed at a stage IB and had a mean disease-free interval of 48.6 months. Recurrence rate was 23% (6 of 26 patients), with a mean interval of 40 (7–74) months and stage of disease was IB in three of them, above IB in two of them and unknown in one of these six patients. Two patients (7.6%) died of disease at 28 and 38 months.

Out of the eight patients with MMMTs, five were diagnosed at stage IB and three above IB. Five of these eight patients (62.5%) had a recurrence with a mean disease-free interval of 46 months, whereas 2 of 8 (25%) died of the disease at 7 and 74 months.

Out of 34 patients, 15 had lymphadenectomy and positive lymph nodes were found on 3 of them (2 of 7 patients with MMT and 1 of 27 patients with adenocarcinoma).

It appears that the MMMTs are more aggressive since they were diagnosed at a more advanced stage and had worse outcomes.

All the patients except one were treated with hysterectomy as the primary treatment.

Advanced stage disease of adenocarcinoma seemed to respond to radiotherapy, but for the MMMTs the combination of chemotherapy with radiotherapy appears to be preferable.

A summary of the cases reported in the literature so far is presented in Table 1.3 5–7 10–13

Table 1.

| Cases reported author/year | Age | Presenting symptom | Immunochemistry |

Primary treatment | Adjuvant treatment | Stage | Recurrence treatment and outcome in months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||||

| Adenocarcinomas | ||||||||

| 1. This case/2012 | 64 | None | AE1/AE3 EMA E cadherin, vimentin, CK7, CD10 focally, calretinine occasional cells | CEA, CK20, TTF1, GCDFP | RAH/BSO pelvic N | None | IB No LVSI | None at 6 |

| 2. Fukunanga/2007 | 46 | Irregular vaginal bleeding/suspicious Cx | CAM5.2 CK7, EMA, p53 chromogranine focal, calretinine occasional cells | CEA, CD10 synaptophysin vimentin oestrogen progesterone | TAH/BSO, pelvis N omentectomy | None | IB | None at 4 |

| 3. Stephanie Yap/2006 | 54 | PMB | CK7, CAM5.2 EMA | Chromograin synaptophysin CD10, CEA vimentin, inhibin calretinine, oestrogen | RAH/BSO aortic/pelvic N | RT external beam 5040 cGy + intracav. 1275 cGY | IB, LVSI | None at 37 |

| 4. Angeles/20044 | 47 | HMB pelvic mass | AE1/AE3 CK7, CK19, EMA, Ca125 oestrogen progesterone CD10 focal | TAH/BSO | RT caesium implants | IB | None at 12 | |

| 5. Bagué et al/2004 case 1 | 41 | AUB | α-Inhibin | TAH, BSO, pelvic N app | RT | IB1 | None at 137 | |

| 6. Bagué et al/200410 case 3 | 24 | N/A | α-Inhibin | N/A | N/A | IIA | N/A | |

| 7. Bagué et al/200410 case 4 | 45 | PCB | Vimentin focal CD10 focal | α-Inhibin | TAH, USO | None | IB1 | None at 37 |

| 8. Silver et al/20013 case 1 | 62 | PMB | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO | None | IB | None at 18 |

| 9. Silver et al/20013 case 2 | 47 | Uterine prolapse | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO | None | IB | None at 25 |

| 10. Silver et al/20013 case 3 | 40 | CIN in smear | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO | None | IB | None at 38 |

| 11. Silver et al/20013 case 4 | 54 | PMB | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO | None | IB | None at 73 |

| 12. Silver et al/20013 case 5 | 67 | PMB | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO | None | IB | None at 100 |

| 13. Silver et al/20013 case 6 | 72 | AGUS on smear | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO, pelvic N | RT | IB, vaginal cuff | Rectovaginal at 20, ChemoT, none at 30 |

| 14. Silver et al/20013 case 8 | 62 | PMB, endometrial Ca on curete | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO, pelvic N | None | IB | N/A |

| 15. Silver et al/20013 case 9 | 56 | Rt ovarian cystadenoma | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | TAH, BSO, | None | N/A | None at 89 |

| 16. Silver et al/20013 case 10 | 35 | AUB pelvic pain | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR, mCEA | Pelvic RT | IIB | Pelvis at 26, ChemoT, DOD at 38 | |

| 17. Clement et al/19955 case 1 | 46 | HMB/fibroid | EMA, vimentin | TAH, BSO, pelvic N | N/A | IB, (+)pelvic N | None at 24 | |

| 18. Clement et al/19955 case 2 | 34 | HMB | EMA, vimentin | TAH, BSO | N/A | IB, (+)pelvic N | Abdomen at 12, Chemo, none at 24 | |

| 19. Clement et al/19955 case 3 | 71 | AdenoCA on smear, pelvic mass | EMA, vimentin | TAH, BSO, pelvic N | RT | IB + endometrioid adenoCA | Abdomen at 4.5, chemo, DOD at 8.5 (concurrent IIC clear cell ovarian carcinoma) | |

| 20. Clement et al/19955 case 4 | 67 | PMB/Cx mass | EMA, vimentin | TAH, BSO, pelvic N | N/A | IB | N/A | |

| 21. Stewart et al/199311 | 37 | HMB/suspicious Cx | CK1, vimentin chromogranin serotonine | CEA | RAH, BSO, pelvic N | None | IB1 | None at 120 |

| 22. Ferry and Scully/19902 | 55 | Pelvic relaxation | N/A | N/A | Hyst, BSO | RT | N/A | None at 60 |

| 23. Lang et al 1990 case 2 | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | TAH | N/A | IB | N/A |

| 24. Valente and Susin 198712 | 58 | PMB | N/A | N/A | RAH, BSO, pelvic N | None | IB1 | Pelvis, RT, DOD at 28 |

| 25. Buntine/197913 | 48 | Fibroids | N/A | N/A | TAH, BSO | None | N/A | Vaginal at 84, RT, DOD at 108 |

| 26. Mc Gee/1962 | 36 | PCB | N/A | N/A | TAH | None | IB | Pelvis at 72, None, 84 |

| Malignant mixed mesonephric tumours | ||||||||

| 27. Bagué et al/200410 case 6 | 54 | AUB | Vimentine | α-Inhibin | TAH, BSO, PelvicN omentum | None | IIA MMMT | Bowel, DOD AT 7 |

| 28. Bagué et al/200410 case 8 | 62 | N/A | Vimentine | α-Inhibin | TAH, BSO | ChemoRT | IVB | Bone, AWD at 40 |

| 29. Bagué et al/200410 case 9 | 54 | N/A | Vimentine calretinine focal | α-Inhibin | TAH, BSO, Pelvic N omentum | None | IB1 | None at 13 |

| 30. Silver et al/20013 case 7 | 39 | Menorrhagia, Cx fibroid | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR mCEA | TAH, BSO | RT | IB MMMT | Mediastinum at 67, chemo, DOD 74 |

| 31. Silver et al/20013 case 11 | 43 | AUB | AE1/3, CK1, EMA, CK7difuse | CK20, ER/PR mCEA | TAH, BSO, Pelvic N omentum, subphrenic mass | Chemo | IVB MMMT | Bladder/pelvis at 8, RT DOD at 9 |

| 32. Clement et al/19955 case 5 | 37 | PCB | EMA, vimentin SMA, CK1 focal | TAH, BSO, Pelvic N | Chemo | IB MMMT | Abdo at 108, surgery and chemo, omental/hepatic/bone 132, chemo, AWD at 156 | |

| 33. Clement et al/19955 case 6 | 73 | PMB | EMA, vimentin SMA, CK1 focal | TAH, BSO | RT | IB, MMMT | None at 36 | |

| 34. Clement et al/19955 | 39 | AUB | EMA, vimentin | TAH, BSO | N/A | IB | N/A | |

AE1, pan cytokeratine; AGUS, abnormal glandular cells of undetermined significance; AUB, abnormal uterine bleeding; AWD, alive with disease; BSO, bilateral salpingoophorectomy; CAM, low molecular weight cytokeratine; CD10; CEA, carcino embryonic antigen; ChemoT, chemotherapy; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; CK20, cytokeratin 20; Cx, uterine cervix; DOD, died of disease; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; ER/PR, estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor; FP; GCDFP, gross cystic disease fluid protein; HMB, heavy menstrual bleeding; IB No; IIA, stage IIA; LVSI, lymphovascular space invasion; mCEA, monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen; MMMT, malignant mesonephric mixed; N, lymph nodes; N/A, not available; PCB, post coital bleeding; PMB, post menopausal bleeding; RAH, radical abdominal hysterectomy; RT, radiotherapy; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; TTF1, thyroid transcription factor-1.

Learning point.

Though the incidence of such tumour is rare, one should consider the above diagnosis in cervical tumours presenting the characteristics mentioned above.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Holland-Frei. Histologic classification of epithelial tumors. In: Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichsellbaum RR, et al. eds. Cancer medicine. 6th edn. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferry JA, Scully RE. Mesonephric remnants, hyperplasia, and neoplasia in the uterine cervix. A study of 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14: 1100–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver SA, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Mezzetti TP, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix: a study of 11 cases with immunohistochemical findings. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angeles RM, August CZ, Weisenberg E. Pathologic quiz case: an incidentally detected mass of the uterine cervix. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:1179–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clement PB, Young RH, Keh P, Ostör AG, et al. Malignant mesonephric neoplasms of the uterine cervix. A report of eight cases, including four with a malignant spindle cell component. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1158–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukunaga M, Takahashi H, Yasuda M. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Pathol Res Pract 2008;204:671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yap OW, Hendrickson MR, Teng NN, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2006;103:1155–8.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton O, Jamison J, Wilson R, et al. P16 Immunoreactivity in unusual types of cervical adenocarcinoma does not reflect human papilloma virus infection. Histopathology 2010;57:342–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabban JT, McAlhany S, Lerwill MF, et al. PAX2 distinguishes benign mesonephric and mullerian glandular lesions of the cervix from endocervical adenocarcinoma, including minimal deviation adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Patol 2010;34:137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagué S, Rodríguez IM, Prat J. Malignant mesonephric tumors of the female genital tract: a clinicopathologic study of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:601–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart CJ, Taggart CR, Brett F, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix with focal endocrine cell differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valente PT, Susin M. Cervical adenocarcinoma arising in florid mesonephric hyperplasia: report of a case with immunocytochemical studies. Gynecol Oncol 1987;27:58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buntine DW. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix of probable Wolffian origin. Pathology 1979;11:713–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]