Abstract

Non-operative management is the management of choice for haemodynamically stable patients with blunt splenic injury. However, coexistent liver cirrhosis poses significant challenges as it leads to portal hypertension and coagulopathy. A 52-year-old man sustained blunt abdominal trauma causing low-grade splenic injury. However, he was found to have liver cirrhosis causing haemodynamic instability requiring emergency laparotomy. His portal hypertension led to severe bleeding only controlled by aortic pressure and subsequent splenectomy. Mortality from emergency surgery in cirrhotic patients is extremely high. Despite aggressive resuscitation, they may soon become haemodynamically unstable. Therefore, traumatic splenectomy may be inevitable in such patients with portal hypertension and splenomegaly secondary to liver cirrhosis even in low-grade injury.

Background

Non-operative management (NOM) has become the management of choice for adult haemodynamically stable patients with blunt splenic injury, an overall success rate ranging from 61% to 83% has been reported.1–3 Attempting to manage unstable patients with blunt splenic injury non-operatively may result in preventable deaths.4

Coexistent liver cirrhosis in such haemodynamically unstable patients is complicated by the presence of coagulopathy and portal hypertension.5 Consequently, escalation of intraoperative bleeding in such critical patients is inevitable. We present a rare case of traumatic splenectomy in a cirrhotic patient due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol liver disease.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old male was brought in by ambulance to accident and emergency having been assaulted. He was clearly intoxicated and had bilateral chest wall pain, particularly, in the left lower ribs on deep inspiration. Detailed history was very difficult to obtain even in the presence of two interpreters due to alcohol abuse. On arrival, his Glasgow Coma Scale was 14/15, pulse 67 beats/min, blood pressure 92/49 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18/min, O2 saturation 96% on room air, temperature 36.0°C and blood glucose of 5.9 mmol/l.

Investigations

Further examination and plain x-ray films revealed a swelling and abrasion over his left maxilla, laceration of left elbow and lips, broken teeth, tenderness in the left upper quadrant region, fractures of the left 4th to 9th and right 5th to 8th and left pleural effusion. Laboratory blood results showed urea and electrolytes within normal ranges, haemoglobin 13.5 g/dl, white cell count 7.1×10−9/l, packed cell volume 0.39 l/l, platelets of 77.000 per microlitre, international normalised ratio (INR) 1.5, prothrombin time 16.5 s, aspirate transaminase 128 u/l, alkaline phosphatase 129 u/l, albumin 35 g/l and elevated bilirubin 28 umol/l with Child-Pugh’s class B.

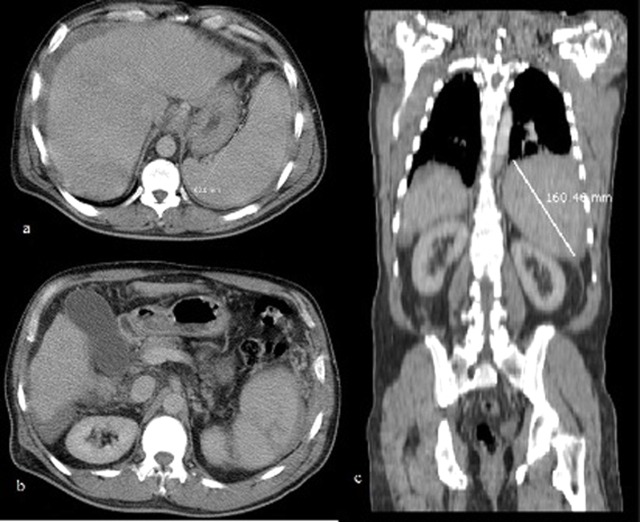

Chest and abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast (figure 1) showed an enlarged spleen with evidence of free intraperitoneal blood, cirrhotic liver and left-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 1.

CT scan: (a) cross sectional view showing splenomegaly and cirrhotic liver, (b) intraperitoneal free fluids and spleen laceration, (c) coronal view.

Treatment

Resuscitation involved intravenous infusion of 500 mls succinylated gelatin (volplex), 2 litres of Hartmann’s solution 4.1 ml/min, 2 units of blood 4.1 ml/min, 1 unit fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K 10 mg intravenously and frusemide 10 mg. Hourly urine output with resuscitation reached 120–150 ml/h. Despite resuscitation, the patient remained haemodynamically unstable with blood pressure of 75/50 mm Hg with constant dropping of Hb 10.6 g/dl, packed cell volume 0.31 l/l, reducing platelets (65.000) and ensuing coagulopathy (INR 1.6, prothrombin time 17.3).

The patient proceeded to emergency laparotomy at which over 2 litres of intraperitoneal blood, ongoing bleeding from a splenic laceration (figure 2), advanced liver cirrhosis and a small bowel mesenteric haematoma were found. Copious amount of bleeding with near impossible views occurred due portal hypertension. This led to profound hypotension that was only controlled with application of aortic pressure initially with the fist and later with the aortic spoon until satisfactory control achieved of vascular pedicles and of multiple minor bleeding sites. Intraoperatively, Hb dropped to 5.3 g/dl, platelets 61 000, INR 2.8 and prothrombine time 28.2 s. The patient required 21 units of blood, 11 units of fresh frozen plasma and 2 cryoprecipitate and 1 unit of platelets. The spleen was removed and its bed packed with gauze roll in view of the deranged clotting, low platelets and the profound bleed which was brought out through a separate stab wound in left upper quadrant.

Figure 2.

Specimen: spleen measuring 165×135×55 mm.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient returned to theatre in 48 h for second look by laparoscopy. No active bleeding was seen, a drain was inserted. Subsequent hepatitis screen revealed hepatitis C positive. Interestingly, his postoperative liver function tests showed slight but persistent improvement trend. The patient was discharged from hospital 2 weeks later to be followed up in the gastroenterology clinic as an outpatient.

Discussion

NOM of blunt splenic injuries has gained popularity since 1960s when it was advocated by paediatric surgeons mainly to avoid the fatal complication of postsplenectomy sepsis.6 By the 1980s NOM of splenic injury had been shown to be safe and effective.7–9

Liver cirrhosis is among the top ten causes of death in the Western world, largely as a result of alcohol abuse. Up to 15% of chronic alcoholics develop liver cirrhosis.10 Hepatitis C infection is also a significant contributor to liver disease, particularly in the third world countries. 15–25% of HCV infections are estimated to progress to severe liver disease, leading to liver cirrhosis in 20% of persistently infected individuals.11 12

Mortality from emergency surgery in cirrhotic patients is as high as 86%.13 Coagulopathy and portal hypertension lead to chronically congestive splenomegaly, deficiency of coagulation factors with potential for serious postoperative complications and high mortality.14–16 Although, it has been reported that haemostasis may be achieved in blunt splenic injury.17 In our case, the presence of portal hypertension and thrombocytopenia made haemostasis very difficult to achieve.

Fang et al18 the only identifiable study which looked at traumatic splenectmy with coexistent liver cirrhosis, looked at the NOM of patients with splenic trauma over 5 years period in a centralised trauma centre in Taiwan. They identified 12 patients with coexistent liver cirrhosis and blunt splenic injury and Child-Pugh’s class A and B. The amount of blood transfusion within 72 h after admission for these 12 patients ranged from 4 to 26 units. Patients with coexistent liver cirrhosis and blunt splenic injury had a significantly higher NOM failure rate compared with non-cirrhotic patients of the same cohort (92% vs 19%). They found that despite aggressive transfusion, all patients soon became haemodynamically unstable and required emergent laparotomy18 which they advocate along with aggressive transfusion of fresh frozen plasma in patients with severely deranged clotting regardless of haemodynamic status.18

Intraoperative transfusion requirements may be diminished by judicious use of aortic compression in the presence of difficult views and bleeding. Gauze roll packing and second look laparoscopy for pack removal are useful techniques for managing haemodynamic status in presence of portal hypertension with deranged clotting. Perhaps, laparostomy at first operation and second look laparoscopy is an alternative.

Our patient’s deranged liver function tests secondary to his hepatitis C showed slight but persistent improvement postoperatively which perhaps related to his splenectomy. Similar effect was noted by Murata et al19 who, in a case series of 12 patients, found that splenectomy improved liver functions in patients with liver cirrhosis. They suggest that splenectomy could be used as a supportive therapy for patients waiting for liver transplantation. However, the long-term effects of splenectomy on liver functions remain largely unknown with scarcely available data in the literature to prospectively evaluate these effects.

Learning points.

-

▶

Patients with blunt splenic injury are managed non-operatively when haemodynamically stable.

-

▶

Meticulous perioperative preparation is required for cirrhotic patients with possible high intraoperative transfusion requirements.

-

▶

Traumatic splenectomy may be inevitable in patients with portal hypertension and splenomegaly secondary to liver cirrhosis even in low grade injury.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Sartorelli KH, Frumiento C, Rogers FB, et al. Nonoperative management of hepatic, splenic, and renal injuries in adults with multiple injuries. J Trauma 2000;49:56–61; discussion 61–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dent D, Alsabrook G, Erickson BA, et al. Blunt splenic injuries: high nonoperative management rate can be achieved with selective embolization. J Trauma 2004;56:1063–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson JD. Changes in the management of injuries to the liver and spleen. J Am Coll Surg 2005;200:648–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvan DA, Peitzman AB. Failure of nonoperative management of abdominal solid organ injuries. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006;12:590–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugawara Y, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, et al. Splenectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and hypersplenism. J Am Coll Surg 2000;190:446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutledge R. The increasing frequency of nonoperative management of patients with liver and spleen injuries. Adv Surgery 1997;30:385–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Radin R, et al. Nonoperative treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs: a prospective study. Arch Surg 2003;138:844–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. J Trauma 2005;58:492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein DM, Scalea TM. Nonoperative management of spleen and liver injuries. J Intensive Care Med 2006;21:296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddrey WC. Alcohol-induced liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2000;4:115–31, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001;345:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alter HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis 2000;20:17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aranha GV, Greenlee HB. Intra-abdominal surgery in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Arch Surg 1986;121:275–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maull KI, Turnage B. Trauma in the cirrhotic patient. South Med J 2001;94:205–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahlstrom K, Ney AL, Jacobson S, et al. Trauma in cirrhotics: survival and hospital sequelae in patients requiring abdominal exploration. Am Surg 2000;66:1071–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansour A, Watson W, Shayani V, et al. Abdominal operations in patients with cirrhosis: still a major surgical challenge. Surgery 1997;122:730–5; discussion 735–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pachter HL, Guth AA, Hofstetter SR, et al. Changing patterns in the management of splenic trauma: the impact of nonoperative management. Ann Surg 1998;227:708–17; discussion 717–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang JF, Chen RJ, Lin BC, et al. Liver cirrhosis: an unfavorable factor for nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury. J Trauma 2003;54:1131–6; discussion 1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murata K, Ito K, Yoneda K, et al. Splenectomy improves liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology 2008;55:1407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]