Abstract

Gallstone ileus is a rare but significant cause of intestinal obstruction particularly among the elderly population. Symptoms are often vague and therefore a high suspicious index is required for successful diagnosis. In this report, we present the case of an 87-year-old gentleman with a background history of cholelithiasis and ileostomy for ulcerative colitis who was admitted with a 24-h history of his stoma not functioning. He had an abdominal x-ray and CT which were consistent with small bowel obstruction with no identifiable cause. He underwent an examination of his stoma under general anaesthesia which revealed a 2.5 cm gallstone wedged several centimetres near the entry point of the stoma. The purpose of this report is to highlight the importance of considering gallstones as a potential cause of a non-functioning stoma in any patient with a significant history of cholelithiasis.

Background

Gallstone ileus (GI) is a rare complication of cholelithiasis occurring in approximately 0.5% of patients. It is thought to be the cause of mechanical intestinal obstruction in 1–4% of patients.1 In the elderly population, GI accounts for 25% of non-strangulated small bowel obstruction.2 Therefore early diagnosis is required to avoid significant mortality and morbidity.

Case presentation

We report the case of an 87-year-old gentleman who presented to our accident and emergency department with a 24-h history of abdominal pain, abdominal distension and his stoma not functioning. This gentleman had a history of a subtotal colectomy with ileostomy approximately 39 years previously for ulcerative colitis.

He had recently been admitted to our department 4 weeks prior with cholangitis and subsequently underwent an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancretography (ERCP) after a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography confirmed multiple stones within the common bile duct (figure 1). The initial ERCP demonstrated an impacted stone at the papilla of the gallbladder and a further 2 cm angular gallstone within the mid-duct. A biliary sphincteromy was performed, a double pig-tailed bilary stent inserted to the hilum and a 7-cm 5F pancreatic stent inserted to reduce incidence of pancreatits. Two weeks after the initial ERCP a further ERCP was conducted to remove the pancreatic stent. Again, multiple stones were noted within the common bile duct, some of which were removed by balloon and basket and a further large stone fragmented by lithotripsy. The pigtailed stent was left in situ. Owing to the complexity of the previous ERCPs and the numerous gallstones identified, it was decided that a final ERCP would be needed but this would be conducted as an outpatient.

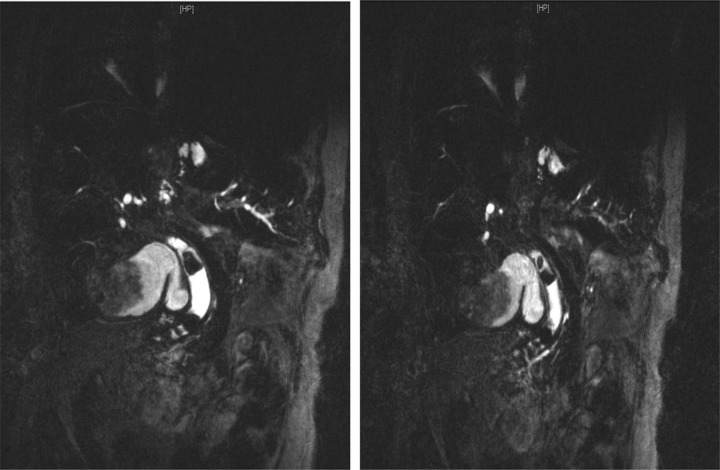

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography 4 weeks prior to admission demonstrating marked biliary dilatation and gallstones within the main bile duct.

On admission our gentleman had no fever, with stable observations. The abdomen was soft but distended with sluggish bowel sounds. Abdominal examination demonstrated no obvious hernias. Stoma examination revealed slight erythema around the site. A plain abdominal x-ray was done on admission which demonstrated dilated small bowel loops (figure 2). He had a CT scan of the abdomen, which was consistent with small bowel obstruction (figure 3). As the cause of obstruction was not identifiable on CT and a more thorough examination of the stoma was limited due to pain, it was decided that further examination of the stoma would be performed under general anaesthesia. This found a gallstone of approximately 2.5 cm lodged several centimetres near the entry point of the ileostomy. This was removed and over the following 24 h and the stoma gradually begun to function. The patient was discharged after 7 days in hospital with a pre-assessment appointment for cholecystectomy.

Figure 2.

Abdominal x-ray demonstrating dilated small bowel loops.

Figure 3.

CT abdomen consistent with small bowel obstruction.

Investigations

White count cell 16.4×109, platelets 243×109 C-reactive protein 68 mg/l, aspartate aminotransferase 16 IU/l, alkaline phosphatise 246 IU/l and bilirubin 24 IU/l.

Abdominal x-ray: dilated small bowel loops.

CT abdomen: intrahepatic dilatation, common bile duct diameter of 18 mm, small bowel dilatation which were air and fluid filled and consistent with small bowel obstruction.

Treatment

Examination under anaesthesia revealing a 2.5 cm gallstone several centimetres near the entry point of the ileostomy.

Outcome and follow-up

Three months after discharge the patient had recovered well. He had undergone his final ERCP which revealed a slight stricture at the distal duct, approximately 3 cm from the papilla. He was currently waiting for a pre-assessment appointment for his cholecystectomy.

Discussion

Mechanical causes of bowel obstruction can range from adhesion to hernias to inflammatory bowel disease. Gallstones, however, are a rare but potentially serious cause of small bowel obstruction particularly among the elderly population.1

The obstructing stone originates within the gallbladder and may then erode into the gastrointestinal tract creating a fistula. The commonest site for a fistula is the duodenum, but these may occur anywhere within the gastrointestinal tract.1 The site of impaction is most commonly within the terminal ileum, ileocaecal valve and jejunum as these have narrower lumens and less GI peristalsis.

Symptoms of GI are usually non-specific and subtle thus making diagnosis extremely difficult.2 Symptoms may be intermittent due to passage of the stone or relate to the site of obstruction. Patients may present with weight loss or features of bowel obstruction. Rigler’s triad consists of mechanical obstruction pneumobilia and an ectopic gallstone within the bowel lumen is present in approximately 35% of patients.3 4 CT abdomen remains the main imaging tool in diagnosis and management of GI.4

The treatment goal of GI is early relief of intestinal obstruction. The rarity of the clinical condition means that there is no uniform surgical approach to management. Enterolithotomy alone without follow-up biliary surgery is increasingly becoming more popular particularly among the elderly population. Other surgical techniques include a one-stage procedure encompassing enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and fistula repair. This approach is however associated with a higher death rate and as such reserved for patients with lower surgical risks.3

Learning points.

Gallstone ileus (GI) should be considered in all elderly patients with a significant history of cholelithiasis presenting with features of bowel obstruction.

A meticulous examination of a non-functioning stoma may be crucial in excluding GI as a potential cause of symptoms.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg 1994;60:441–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayantunde A, Agrawal A. Gallstone Ileus: diagnosis and management. World J Surg 2007;31:1294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou J-W, Hsu C-H, Liao K-F, et al. Gallstone ileus: report of two cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:1295–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu C-Y, Lin C-C, Shyu R-Y, et al. Value of CT in the diagnosis and management of gallstone ileus. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:2142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]