Description

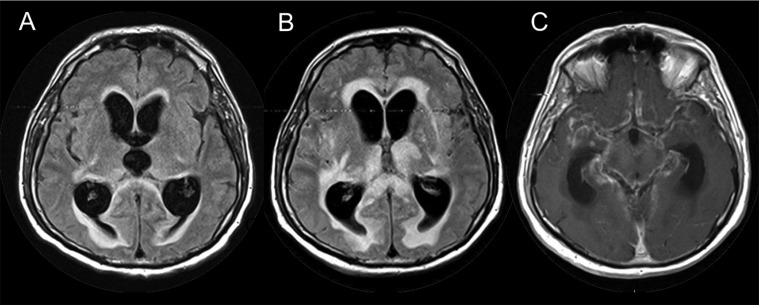

An immunocompetent (HIV-negative) 69-year-old Caucasian man with a history of paramedian pontine acute ischaemic stroke requiring intravenous thrombolysis 1 year earlier (ataxia as sequelae only) was admitted with a 7-day history of fever. The patient was in a confused state at admission, with known ataxia but without other neurological signs. His mental status worsened 4 days after admission with occurrence of a coma and neck stiffness. Mild hydrocephalus was observed on a first MRI (figure 1A), and ventriculoperitoneal shunt was not performed. Central nervous system tuberculosis was finally diagnosed (cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collected 5 days after admission contained 138 white cells/mm3 with acid-fast bacilli on direct examination; the glucose CSF/blood ratio, CSF lactate and protein were 0.9/10 mmol/l, 13.7 mmol/l and 4.64 g/l, respectively). Despite administration of antituberculous chemotherapy (intravenous rifampin–isoniazid–ethambutol and oral pyrazinamid, introduced 7 days after admission) and intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kg/day), the mental status progressively worsened. At day 18, hydrocephalus persisted on MRI with the appearance of (i) contrast-enhanced meningeal thickening; (ii) irregular aspect of middle cerebral arteries; and (iii) large zones of cerebral infarction (reaching basal nuclei, cerebral trunc, pedoncules and temporal lobes) suggestive of vasculitis (figure 1B,C). Traditional cultures confirmed susceptible tuberculosis at day 15. The patient died at day 20.

Figure 1.

(A) First cerebral MRI performed at admission in the intensive care unit; T2 FLAIR sequence shows hydrocephalus with tetraventricular expansion and transependymal resorption. (B) Second MRI performed 11 days after the first MRI while the clinical state did not improve. T2 FLAIR sequence shows the persistence of hydrocephalus and new cerebral infarction lesions with regard to both the thalamus and the caudate nucleus, suggesting of vasculitis; T1 sequence with the injection of gadolinium. (C) Meningeal thickening and enhancement consistent with intense inflammatory lesions.

Hydrocephalus, meningeal thickening and cerebral infarction are known to be possible complications during subacute or chronic tuberculous meningitis.1–3 Hydrocephalus is known to increase intracranial pressure that leads to a reduction of the cerebral perfusion. Basal arachnoiditis, which is often associated, leads to vasculitis, small vessels occlusion and cerebral infarction.1 Here, cerebral infarctions occurred rapidly during the course of the disease. Pre-existing arterial lesions could have facilitated the occurrence of rapid cerebral infarction and might partially explain the fulminant fatal evolution. Indeed, as tuberculous meningitis is mainly associated with leptomeningeal exsudates located in the interpedoncular fossa, vasculitis might precipitate thrombus formation if basal vessels already harbour pre-existing artherosclerosis lesion.1 This case illustrates the poor outcome associated with stroke in tuberculous meningitis,1–3 stressing the need for optimal acute care management and new therapeutic approaches.

Learning points.

Vasculitis might occur early in the clinical course of tuberculous meningitis.

Hydrocephalus, vasculitis and cerebral infarction might facilitate fulminant fatal evolution, despite prompt introduction of antituberculous therapy and corticosteroids.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Misra UK, Kalita J, Maurya PK. Stroke in tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Sci 2011;303:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalita J, Misra UK, Nair PP. Predictors of stroke and its significance in the outcome of tuberculous meningitis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;18: 251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anuradha HK, Garg RK, Agarwal A, et al. Predictors of stroke in patients of tuberculous meningitis and its effect on the outcome. QJM 2010;103:671–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]