Abstract

Arnold-Chiari malformations are a group of congenital or acquired defects associated with the displacement of cerebellar tonsils into the spinal canal. First described by Chiari (1891), this has various grades of severity and involves various parts of neuraxis, for example, cerebellum and its outputs, neuro-otological system, lower cranial nerves, spinal sensory and motor pathways. The symptomatology of Arnold-Chiari malformations may mimic multiple sclerosis, primary headache syndromes, spinal tumours and benign intracranial hypertension. We highlighted a case of Chiari type I malformation, who presented with posterolateral ataxia associated with significant vitamin B12 deficiency. The patient was supplemented with vitamin B12 injections and showed remarkable improvement at follow-up after 3 months.

Background

Chiari malformations are a group of abnormalities of the hindbrain, affecting the structural relationships among cerebellum, brainstem, the upper cervical cord and the basal calvarium. The Chiari type I is the most common among four subtypes, and is characterised by descent of cerebellar tonsil below the foramen magnum. The syringomyelia is often associated with Arnold-Chiari malformation. The symptoms of syringomyelia are a constellation of features attributed to the hindbrain anomaly and those due to the destruction of the spinal cord. The myelopathic presentation consists of either a central cord syndrome, spastic or ataxic paraparesis.1 This entity is a great mimic in the sense that many times the symptom complexes thought to be due to the disease is in fact caused by associated diseases of the brain and spinal cord.2 This leads to an unnecessary decompressive surgery with persistence of symptoms postoperatively. We present a similar case of Chiari malformation type I, who presented with a spinal cord syndrome but on investigation was found to have severe B12 deficiency. The vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to a wide range of haematological, neurological and psychiatric manifestations.3 Our objective is to convey the message that one should never be hasty in operating such cases without peeping into the close mimics.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old man, vegetarian, presented with a 6-month history of intermittent urinary incontinence and a 2-month history of paraesthesia of lower limb and difficulty in walking. The symptoms were progressive, so that the patient gradually had slippage of footwear without awareness. The swaying used to get increased in darkness and with eye closure (during washing of the face). There was no history of dysphagia, ptosis, diplopia, nasal regurgitation, neck pain, Lhermitte's symptom, band-like sensation or flexor spasm. There was no history of diabetes, tuberculosis, hypertension, sexual promiscuity, abdominal surgery or chronic diarrhoea. The personal history did not reveal addiction to alcohol. The general examination was normal except for mild anaemia. The speech assessment revealed mild dysarthria with normal cranial nerves examination. The motor system evaluation showed normal bulk, tone, power and brisk deep tendon reflexes except for ankle reflex that was absent bilaterally. The abdominal reflex was absent and plantars demonstrated equivocal response. The sensory examination revealed impaired vibration and joint position sense below the anterior superior iliac spine. Romberg's test was positive and cerebellar signs were positive in lower limbs substantiated by an impaired knee heel test and a tandem walk. Meningeal signs were absent and skull and spine were normal.

Investigations

Routine haemogram showed Hb 11.3 g%, total leucocyte count 6700/mm3 with polymorphs 67%, platelet count 1.67 lakhs/mm3 and peripheral blood picture revealed macrocytosis. The biochemical parameters had following results: Na 141 mmol/l, K+ 4.2 mmol/l, calcium 1.10 mmol/l, serum urea 29 mg/dl, creatinine 0.5 mg/dl and random blood sugar 82 mg/dl. The thyroid function test demonstrated no abnormality. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was normal. The viral study in serum and CSF for dengue virus, Japanese encephalitis virus and HIV revealed normal findings. The antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor were non-reactive in sera.

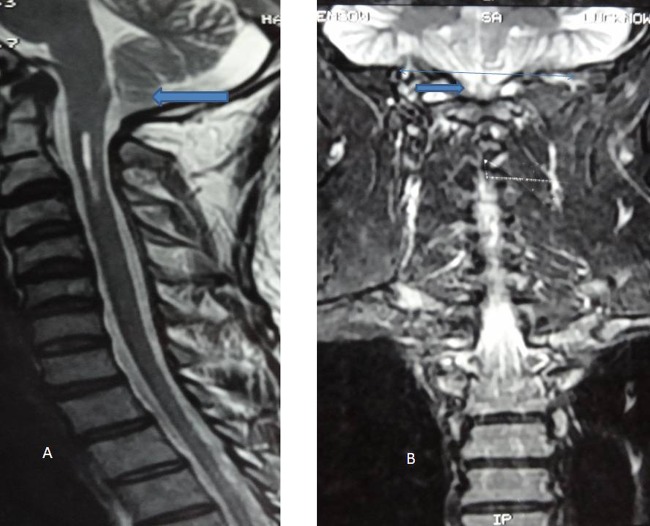

The nerve conduction study showed non-recordable sural nerves on both sides. The visual-evoked potentials demonstrated normal findings. MRI of cervical spine study revealed peg-shaped tonsil of cerebellum, herniating below the foramen magnum and syrinx in cervical cord extending from C1 to the upper border of C3 vertebra suggestive of Arnold-Chiari malformation type I (figures 1 and 2). The level of B12 was found to be very low 97.59 pg/ml (normal range 211 to 894 pg/ml). The serum homocysteine level was elevated to 25.2 µmol/l (normal range: 2.2 to 13.2 µmol/l). The serum folate study revealed normal results.

Figure 1.

(A) MRI T2-weighted saggital image demonstrated tonsillar herniation. (B) MRI T2-weighted image on coronal section revealed tonsillar herniation below the foramen magnum.

Figure 2.

MRI, T2-weighted image of same patient showed the presence of syrinx.

Table 1.

Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency

| Diagnosis | Clinical manifestations |

|---|---|

|

|

Differential diagnosis

Multiple sclerosis, spinal cord neoplasm, visual disorders, infectious myelopathy, neuro-otological disorders and intracranial hypertension.

Treatment

The patient was supplemented with intramuscular vitamin B12 injections according to the protocol. The patient was injected intramuscularly 1000 μg of vitamin B12 initially on daily basis for a week and then weekly for a month and receiving once-monthly injections.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient showed significant improvement at follow-up assessment at 3 months. After 6 months, he recovered to his normal physical and mental capacity.

Discussion

The prevalence rate of Arnold-Chiari type I malformation ranges from 0.1% to 0.5% according to epidemiological studies, with female preponderance. The radiological definition of Chiari type I is descent of cerebellar tonsils 3 to 5 mm below the foramen magnum. The usual age of onset ranged from the second to the fourth decade. In one-third to half of the cases,4 Arnold-Chiari type I malformation is associated with syringomyelia and the latter is usually in cervical and cervicothoracic region as in our case. Various theories regarding the pathophysiology of this malformation have been proposed, of which the most accepted one is the ball valve theory where systolic descent of tonsils into the spinal subarachnoid space creates a one-way valve causing block of CSF and increasing its pressure in the upper cervical cord. The pulsatile pressure is transmitted to the central canal through the virchow robbins spaces causing a syrinx.5

Symptoms result either due to compression of the medulla, spinal cord and cerebellum or due to blockage of CSF. The former includes lower cranial nerve palsies, spastic or ataxic paraparesis, bladder dysfunction, gait abnormality and tremor and latter results in chronic headache because of hydrocephalous.4

Unlike the rarity of this anomaly, the incidence of vitamin B12 deficiency may be up to 50% of the elderly population, more so in Indians and particularly in vegetarians.6 The neurological manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency comprises peripheral neuropathy, craniopathy, myelopathy, dementia, psychiatric disorders and increased propensity for ischaemic strokes (table 1).7

Decompressive suboccipital craniectomy is the preferred treatment modality for Chiari malformation.8 As Chiari I mimics many other diseases such as multiple sclerosis, spinal cord tumours, primary headache syndromes because of the involvement of multiple levels of neuraxis; these differential diagnoses should be excluded and treated to prevent failure of surgery. In our case we similarly went for treatment of coexistent vitamin B12 deficiency before planning for any invasive procedure.

Learning points.

Arnold-Chiari malformation is increasingly recognised with the advent of advanced neuroimaging techniques.

Arnold-Chiari malformation can be asymptomatic or can produce symptoms depending on the type of malformation and associated anomalies including syringomyelia and hydrocephalus.

The various clinical conditions including multiple sclerosis, spinal cord tumour, visual disorders, vertigo, intracranial hypertension and dissociative disorders can be attributed to Arnold-Chiari malformation.

The vitamin B12 deficiency, myelopathic syndromes should be included in mimics of Arnold-Chiari malformation.

The vitamin B12 deficiency neurological syndromes are completely treatable disorders provided the supplementation of vitamin B12 instituted in the early phase of illness.

The unnecessary surgical intervention can lead to frustration and disappointment among patients, if associated conditions are not explored.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Geroldi C, Frisoni GB, Bianchetti A, et al. Arnold-Chiari malformation with syringomyelia in an elderly woman. Age Ageing 1999;28:399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bejjani GK. What do tonsillar herniation and idiopathic intracranial hypertension have in common? Successful management of recurrent Chiari malformation with CSF diversion. Transactions of the 12th World Congress of Neurosurgery; Sydney, Australia: WFNS, 2001:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milhorat TH, Chou MW, Trinidad EM, et al. Chiari I malformation redefined: clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery 1999;44:1005–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menezes AH. Chiari I malformations and hydromyelia: complications. Pediatr Neurosurg 1991;17:146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennypacker LC, Allen RH, Kelly JP, et al. High prevalence of cobalamin deficiency in elderly outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:1197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misra UK, Kalita J, Das A. Vitamin B12 deficiency neurological syndromes: a clinical, MRI and electrodiagnostic study. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 2003;43:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takigami I, Miyamoto K, Kodama H, et al. Foramen magnum decompression for the treatment of Arnold Chiari malformation type I with associated syringomyelia in an elderly patient. Spinal Cord 2005;43:249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]