Abstract

Hyperkalemia is a medical condition that requires immediate recognition and treatment to prevent the development of life-threatening arrhythmias. Pseudohyperkalemia is most commonly due to specimen haemolysis and is often recognised by laboratory scientists who subsequently report test results with cautionary warnings. The authors present a case of pseudohyperkalemia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia that was the result of white blood cell lysis during phlebotomy. False elevations of potassium from this condition may not be reported with a warning from the laboratory. This places the patient at risk of unnecessary and potentially dangerous treatments. This phenomenon has not been published in the emergency medicine literature to date.

Background

The appropriate identification and treatment of patients with hyperkalemia is necessary to prevent the development of potentially fatal arrhythmias including ventricular fibrillation.1 Potassium levels are frequently measured on patients that present to the emergency department (ED). Often this test is ordered with the specific concern of hyperkalemia, but frequently it is obtained as part of an electrolyte panel drawn for a variety of reasons. Pseudohyperkalemia is a common error in laboratory measurement that can complicate patient care.2

Pseudohyperkalemia is defined as an elevation in measured serum or plasma potassium caused by the cellular release of potassium during phlebotomy or specimen processing.3 Most commonly red blood cell lysis (haemolysis) during phlebotomy is the cause of this error. Emergency physicians are often able to use a variety of clues to identify pseudohyperkalemia. In most laboratories, a chemical analyser measures the sample absorbance against a haemolytic index to deduce the degree of haemolysis, which is then reported with the potassium result. An ECG, while imperfect, may show abnormalities that indicate hyperkalemia.4 A creatinine level can also help as a normal creatinine can be predictive of pseudohyperkalemia.5 Finally, patients with hyperkalemia may exhibit symptoms such as palpitations, paresthesia and neuromuscular weakness.1

We report a case of pseudohyperkalemia that was the result of lysis of white blood cells during phlebotomy. This is a rare but established entity in laboratory medicine.6–8 The clinician unfamiliar with this condition may be confused by elevated potassium levels without accompanying reports of hemolysis. This may result in unnecessary treatments leading to potentially dangerous outcomes such as iatrogenic hypokalemia.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old male with a history of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin presented to the ED with right-sided facial swelling and pain. The patient had recently undergone excision of a malignant lesion on his face, near his right eye. He subsequently developed erythema at the surgical site. The patient completed a course of cytoxan and vincristine chemotherapy for his CLL 1 week prior to presentation.

His initial vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed cellulitis on his right face and orbital region. CT of the orbits revealed no evidence of orbital abscess. The patient was started on intravenous vancomycin for preseptal cellulitis.

Investigations

His first set of laboratory values drawn at 13:20 showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 499.5 (4.5–11 K/μl) with 100% lymphocytes, haemoglobin 11.0 (13.2–17.3 g/dl), platelet count 55 (150–400 K/μl), sodium 134 (136–145 mmol/l), potassium 7.6 (3.5–5.1 mmol/l), chloride 101 (98–107 mmol/l), carbon dioxide 27 (21–31 mmol/l), blood urea nitrogen 38 (mg/dl), creatinine 0.8 (0.9–1.3 mg/dl), glucose 104 (74–106 mg/dl), phosphate 3.4 (2.7–4.5 mg/dl), magnesium 2.3 (1.6–2.6 mg/dl), non-ionised calcium 8.8 (8.6–10.0 mg/dl). No haemolysis was indicated in the accompanying report. An ECG was obtained and interpreted as normal. Treatment for hyperkalemia was initiated which included 10 units insulin, 25 g dextrose, 50 meq sodium bicarbonate and 45 g kayexalate.

A repeat potassium lab drawn at 16:39 remained elevated at 7.8 mmol/l. He continued to be asymptomatic and was given a second dose of kayexalate. A subsequent potassium level drawn at 18:31 was 7.6 mmol/l.

Additional lab work was sent to rule out tumour lysis syndrome: uric acid 6.2 (4.4–7.6 mg/dl), creatine kinase 14 (37–174 U/l), lactate dehydrogenase 334 (100–190 U/l), albumin 3.6 (3.4–4.8 g/dl), total bilirubin 1.7 (<1.5 mg/dl), alkaline phosphatase 88 (38–126 U/l), alanine aminotranferease 10 (10–40 U/l), aspartate aminotransferase 26 (5–34 U/l) and total protein 5.4 (6.4–8.3 g/l).

Another potassium level was drawn at 20:15 and returned 10.4 mmol/l. A repeat ECG was again normal. Two grams of calcium gluconate was administered. The admitting oncologist recommended a potassium redraw with a 21 gauge butterfly syringe into a heparinised tube walked to the lab on ice. This final value yielded 3.4 mmol/l.

Differential diagnosis

Hyperkalemia, pseudohyperkalemia and tumour lysis syndrome.

Outcome and follow-up

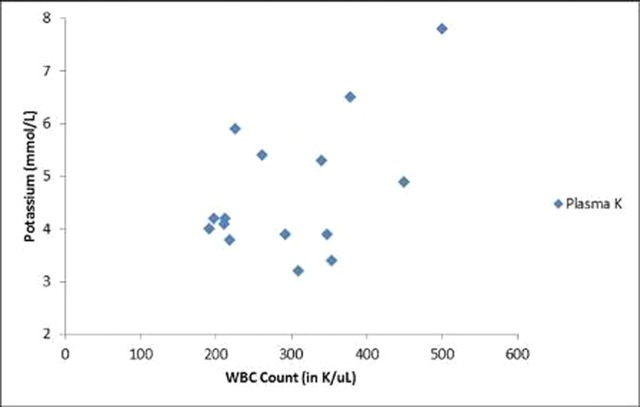

The patient was transported to a telemetry unit where he had an uneventful course during which time his WBC count gradually decreased from 500 to 200 K/μl. His sporadic episodes of pseudohyperkalemia also became less frequent (figure 1).

Figure 1.

As the patient’s white blood cell trended downward from 500 K/μl to below 200 K/μl, sporadic episodes of pseudohyperkalemia became less frequent.

Discussion

Pseudohyperkalemia is a common laboratory error encountered by emergency physicians in clinical practice. Fortunately, it is most often related to specimen haemolysis and laboratories routinely provide warnings of this when they report potassium levels.6 ECG findings and clinical context can also help identify pseudohyperkalemia and avoid inappropriate treatments.1 4 5

This case report illustrates the difficulties of identifying pseudohyperkalemia when the laboratory does not report hemolysis. Leukocytosis and thrombocytosis are established causes of pseudohyperkalemia but are relatively rare and therefore less familiar to the average physician in clinical practice. Case reports of this condition have not appeared in the emergency medicine literature to date.7–10

Patients with leukaemias and lymphomas develop pseudohyperkalemia related to WBC fragility. The same mechanical forces that lead to erythrocyte breakdown can also cause WBC lysis, which in turn leads to false potassium elevations in the collected sample.7 It is important to remember to consider tumour lysis syndrome in this patient population as well. In this condition, cell lysis is invivo and unrelated to the method of phlebotomy. Consequently, elevated potassium levels are accurate and may require emergent treatment. In our case, additional laboratory data including a normal uric acid, calcium and phosphate level rendered tumour lysis syndrome unlikely.11

Phlebotomy techniques that increase the risk of pseudohyperkalemia include the use of vacuum tubes, Luer lock syringes, small gauge needles, tourniquets and heparin. Issues related to specimen transport (pneumatic system), handling (delay), or processing (centrifugation) can also contribute to pseudohyperkalemia.3 12–15

Our case also illustrates that often ordering a specimen redraw is not sufficient when pseudohyperkalemia is suspected. Close communication with nursing should take place to ensure a redraw is done with a different technique (eg, obtain whole blood gas or use gentle aspiration via a butterfly needle into non-vaccum tube).9 15

We hope this case report provides further information to emergency physicians faced with an elevated potassium level and the challenge of determining if it is an accurate report or a case of pseudohyperkalemia. EDs that have a large population of patients with haematologic cancers may want to consider discussing this issue with their laboratory leadership. Some experts have suggested that a warning should accompany elevated potassium levels in the setting of extreme leukocytosis.10 13

Learning points.

-

▶

Hyperkalemia is a serious medical condition that must be evaluated and treated promptly as it can lead to fatal arrhythmias.

-

▶

Laboratory errors due to red cell lysis (haemolysis) are frequently reported by critical lab scientists.

-

▶

Leukaemia and lymphoma patients are susceptible to pseudohyperkalemia which can be caused by leucocyte fragility.

-

▶

The subsequent white cell lysis has been attributed to various processing techniques such as phlebotomy (needle size, heparin coated sample tubes, tourniquet use) and specimen transport (pneumatic system) methods.

-

▶

Inappropriate treatment of pseudohyperkalemia can lead to adverse effects such as hypokalemia.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Gibbs MA, Tayal VS. Electrolyte Disturbances. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Seventh Edition New York, NY: Mosby; 2009:1620–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carraro P, Servidio G, Plebani M. Hemolyzed specimens: a reason for rejection or a clinical challenge? Clin Chem 2000;46:306–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellerman PS, Thornbery JM. Pseudohyperkalemia due to pneumatic tube transport in a leukemic patient. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:746–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wrenn KD, Slovis CM, Slovis BS. The ability of physicians to predict hyperkalemia from the ECG. Ann Emerg Med 1991;20:1229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caraballo NT, Buccelletti F. Hyperkalemia from hemolyzed specimens: must they be repeated? Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:S110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischbach FT. A Manual of Laboratory & Diagnostic Tests. Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimeski G, Bird R. Hyperleukocytosis: pseudohyperkalaemia and other biochemical abnormalities in hyperleukocytosis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2009;47:880–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sevastos N, Theodossiades G, Archimandritis AJ. Pseudohyperkalemia in serum: a new insight into an old phenomenon. Clin Med Res 2008;6:30–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruddy KJ, Wu D, Brown JR. Pseudohyperkalemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2781–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colussi G, Cipriani D. Pseudohyperkalemia in extreme leukocytosis. Am J Nephrol 1995;15:450–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard SC, Jones DP, Pui CH. The tumor lysis syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1844–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lippi G, Blanckaert N, Bonini P, et al. Haemolysis: an overview of the leading cause of unsuitable specimens in clinical laboratories. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:764–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HK, Brough TJ, Curtis MB, et al. Pseudohyperkalemia–is serum or whole blood a better specimen type than plasma? Clin Chim Acta 2008;396:95–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellevue R, Dosik H, Spergel G, et al. Pseudohyperkalemia and extreme leukocytosis. J Lab Clin Med 1975;85:660–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng QH, Krahn J. Reverse pseudohyperkalemia in heparin plasma samples from a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Biochem 2011;44:728–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]