Abstract

Study Objectives:

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown to improve both sleep and depressive symptoms, but predictors of depression outcome following CBT-I have not been well examined. This study investigated how chronotype (i.e., morningness-eveningness trait) and changes in sleep efficiency (SE) were related to changes in depressive symptoms among recipients of CBT-I.

Methods:

Included were 419 adult insomnia outpatients from a sleep disorders clinic (43.20% males, age mean ± standard deviation = 48.14 ± 14.02). All participants completed the Composite Scale of Morningness and attended at least 4 sessions of a 6-session group CBT-I. SE was extracted from sleep diary; depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) prior to (Baseline), and at the end (End) of intervention.

Results:

Multilevel structural equation modeling revealed that from Baseline to End, SE increased and BDI decreased significantly. Controlling for age, sex, BDI, and SE at Baseline, stronger evening chronotype and less improvement in SE significantly and uniquely predicted less reduction in BDI from Baseline to End. Chronotype did not predict improvement in SE.

Conclusions:

In an insomnia outpatient sample, SE and depressive symptoms improved significantly after a CBT-I group intervention. All chronotypes benefited from sleep improvement, but those with greater eveningness and/or less sleep improvement experienced less reduction in depressive symptom severity. This suggests that evening preference and insomnia symptoms may have distinct relationships with mood, raising the possibility that the effect of CBT-I on depressive symptoms could be enhanced by assessing and addressing circadian factors.

Citation:

Bei B, Ong JC, Rajaratnam SM, Manber R. Chronotype and improved sleep efficiency independently predict depressive symptom reduction after group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11(9):1021–1027.

Keywords: CBT-I, depression, chronotype, morningnesseveningness, circadian, insomnia, mood

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is an efficacious non-pharmacological treatment for insomnia,1 with comparable short-term efficacy and better long-term maintenance of gains compared to sleep medication.2 Its effectiveness on outcomes beyond sleep has also been demonstrated. For example, CBT-I has been shown to reduce depressive symptom severity and to have other benefits, such as better perceived energy levels, productivity, and self-esteem.3,4 Several studies identified predictors of improvements in insomnia following CBT-I.5,6 However, to the best of our knowledge, factors associated with the effects of CBT-I on depressive symptom severity have not been examined. Given high prevalence of depressive symptoms among insomnia patients, identifying factors associated with depressive symptom reduction after CBT-I could have significant clinical implications, as it could provide clinically relevant information on how to enhance the benefits of CBT-I.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Prevalence of depressive symptoms is high among individuals with insomnia, and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown to improve both sleep and depressive symptoms. Factors associated with depressive symptom reduction after CBT-I have not been well examined and could provide clinically relevant information on how to enhance the benefits of CBT-I.

Study Impact: In a large outpatient insomnia sample, stronger evening preference and less improvement in sleep efficiency independently predicted less reduction in depressive symptom severity following CBT-I. Empirically, this suggested evening preference and insomnia symptoms have distinct relationships with mood; clinically, this raises the possibility that the effect of CBT-I on depressive symptoms could be enhanced by assessing and addressing circadian factors.

The importance of sleep and circadian factors to the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms is well recognized.7 Poor sleep and symptoms of insomnia have been associated with greater depressive symptom severity,8 slower and lower rates of remission from depression,9 and higher risk for depression relapse.10 Chronotype, or morningness-eveningness, refers to an individual's diurnal preference for rest and activity, and is closely associated with the circadian system involved in the regulation of sleep timing. The circadian system and associated chronotype are not only intimately related to sleep duration and quality,11 but have also increasingly been linked to mood and depressive symptomatology. Evening chronotype is associated with higher depressive symptoms in community samples12 and among adults seeking treatments for insomnia,13 as well as with higher prevalence of clinical depression.14 Recently, a study of 253 individuals with major depressive disorder found that greater insomnia severity and eveningness were independently associated with higher risk of non-remission from depression at five-year naturalistic follow-up.15 Taken together, these studies suggest that poor sleep and eveningness, strongly linked to the circadian timing system, might have distinctive involvements in the development and maintenance of depressed mood.

In a large sample of outpatients seeking treatment for insomnia, this study aims to investigate factors associated with depressive symptom reduction after CBT-I, with focuses on the roles of morningness-eveningness and improvement in sleep quality (operationalized as sleep efficiency; primary findings in this study were replicated when self-report sleep quality was examined in place of sleep efficiency). It was hypothesized that stronger evening preference and less improvement in sleep efficiency will be associated with lower reduction in depressive symptoms after CBT-I, after controlling for baseline depressive symptom severity, sleep efficiency, age, and sex.

METHODS

Data were collected as part of routine care from 595 insomnia outpatients who attended group CBT-I between March 1999 and May 2004 at the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) at Stanford University Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent or were exempt by a waiver obtained from the IRB.

Participants

The sample consisted of 419 insomnia patients (43.2% males) with an average age of 48.14 (SD 14.02) years. All patients were referred to group CBT-I after being assessed by a sleep specialist as having significant symptoms of insomnia such that CBT-I was indicated. Patients with coexisting sleep disorders, psychiatric disorders, and medical conditions were not excluded, resulting in a heterogeneous outpatient sample. To be included in this study patients had to (a) be ≥ 18 years old, (b) have received sleep restriction and stimulus control, which are the core CBT-I components (operationalized as not having dropped out before the fourth session,16 when these components were introduced), and (c) have completed the Composite Scale of Morningness.17

Intervention

Treatment consisted of six 90-min group CBT-I sessions with the following treatment components: sleep education (Session 1), relaxation and other stress management techniques (Session 2), stimulus control and sleep restriction (Session 3, and adjusted in subsequent sessions), cognitive therapy and mindfulness principles (integrated into all sessions), and relapse prevention (Session 6). The first 4 treatment sessions were conducted weekly and the last 2 biweekly. Treatment was delivered by licensed psychologists as part of routine clinical care. A week before Session 1, patients attended an initial assessment and orientation to CBT-I and to group therapy. This discussion was led by the same psychologist who provided the treatment, and included information about the efficacy of CBT-I, the general agenda for each therapy session, the limits of confidentiality, etiquette of group therapy, and individual introductions.

Measures

Sleep Diary

Sleep diaries are routinely used to assess sleep in the course of CBT-I, and are standard in insomnia research. In this study, patients were asked to complete sleep diary every morning throughout the entire group program. The diary items covered the following aspects of sleep the night before: lights out (LO), rise time (RT), total sleep time (TST), sleep onset latency (SOL), and time awake after sleep onset (WASO), Subjective Quality (overall sleep quality rated on 1–10, with higher score indicating better perceived sleep). Sleep efficiency (SE) was calculated as the percentage of TST relative to time in bed (TIB, the time between LO and RT). Sleep efficiency provides an index of overall sleep quality for a given night that is meaningful for patients with difficulties with sleep initiation and/or sleep maintenance.

Patients were asked to return the diaries at each session. The sleep diary obtained prior to Session 1 was considered “Baseline” diary. The last sleep diary form returned by a patient was considered as “End” diary, even if it was reported prior to the final group session (see Table 1).

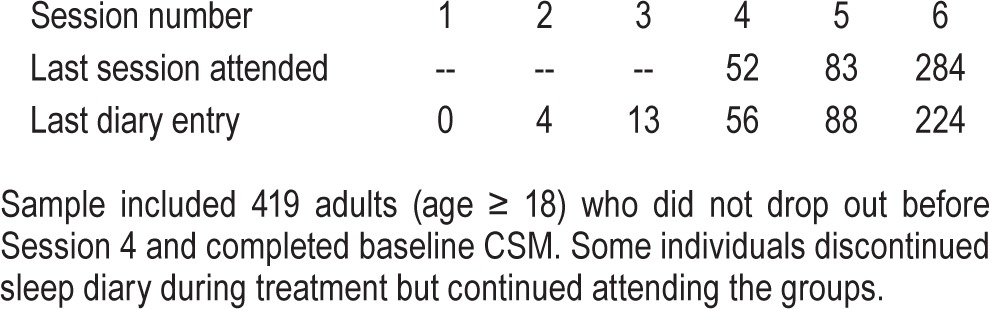

Table 1.

Frequency table for last session attended and End diary obtained.

Chronotype

Chronotype was assessed with the Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM)17 at baseline. It has 13 items asking about preferences for various activities and ease of rising in the morning, and has excellent psychometric properties. The CSM had excellent internal consistency reliability in this study (Cronbach α = 0.91). Higher total scores on CSM indicate more morning preference. Total scores of ≤ 22 are indicative of evening type, 23–43 intermediate type, and ≥ 44 morning type.17 If one or two items were missing, mean replacement was applied; if > 2 items were missing, the entire scale was considered invalid and treated as missing.

Beck Depression Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was administered at Baseline and at the last group session (End). Patients who did not attend the last session did not complete the End BDI. The BDI is a 21-item, well validated self- report scale for assessing symptoms of depression.18 Higher total scores of BDI indicate higher depressive symptoms. Total scores ≤ 9 indicate minimal, 10–18 mild, 19–29 moderate, and ≥ 30 severe depression. If one or two items was missing, mean replacement was applied; if > 2 items were missing, it was considered invalid and treated as missing. In this study, item 16 on sleep was not included in the total scores of BDI to avoid overlap between measurements of insomnia and depressive symptoms. In this study, the BDI demonstrated good internal consistency reliability at both Baseline (Cronbach α = 0.89) and End (Cronbach α = 0.86) assessments.

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary intent-to-treat analyses were conducted to examine whether previous findings that sleep (SE in this study) and depressive symptom severity (BDI scores in this study) improved significantly following CBT-I were replicated in this sample. Specifically, the following analyses were conducted: (a) The change in SE from Baseline to End assessments was examined testing a multilevel model, in which seven daily observations were nested within each individual. The model included a random intercept and random slope based on all available daily data. Session numbers were integrated linearly in the model, and operationalized by dividing session numbers by 6 (i.e., 0 for Baseline days, and 2/6, 3/6, 4/6, 5/6, or 6/6 for End days). This takes into account that End sleep diary was obtained at different sessions during the program, and allows for the linear session slope to be estimated as overall change in SE from Baseline to Session 6. (b) The change between Baseline and End BDI was examined using a latent difference score (LDS)19 model based on Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The LDS of BDI in this step represent change in BDI from Baseline to Session 6.

Primary intent-to-treat analyses examined how chronotype (CSM) and changes in SE are related to changes in depressive symptom severity (BDI) controlling for age, sex, as well as SE and BDI at baseline. A multilevel SEM20 model with the following components were tested: (a) The change in BDI (i.e., LDS of BDI) was predicted by Baseline (i.e., the random intercept) and the change (i.e., the linear session slope) of SE, Baseline BDI, CSM, age, and sex; (b) the change in SE was predicted by Baseline SE, CSM, age, and sex; (c) Baseline SE and BDI were both predicted by CSM, age, and sex; (d) CSM was predicted by age and sex.

Analyses were conducted using R 3.1 and Mplus 7.11 via MplusAutomation 0.6–2. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood, which allows data from all individuals to be included and outperforms list-wise deletion.21 Distributions of all continuous variables were considered normal, except for the BDI, which had a positively skewed distribution. Root square transformation was therefore applied on the total scores of BDI. Two-tailed tests were used with α set at 0.05 for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Missing Data

Frequencies for session attendance and session numbers when the End sleep diaries were obtained are shown in Table 1. Baseline and End sleep diaries were available from 343 (81.9%) and 385 (91.9%) of the sample, respectively. Compared to those who provided End sleep diary, those who only provided Baseline sleep diary scored significantly higher on Baseline BDI (F1, 411 = 17.50, p < 0.001) and had higher Baseline SE (F1, 318 = 4.07, p = 0.04); those who did and did not provide End sleep diary did not differ significantly on CSM or sex. Baseline BDI was available from 413 patients (98.6% of the sample). Among the 284 patients who attended the final session when End BDI was administered, 237 (83.5%) returned valid response. One-way analyses of variance and χ2 test showed no significant differences in Baseline BDI, SE, CSM, or sex between those who returned End BDI versus those who did not.

Preliminary Analyses: Changes in Sleep and Depressive Symptoms

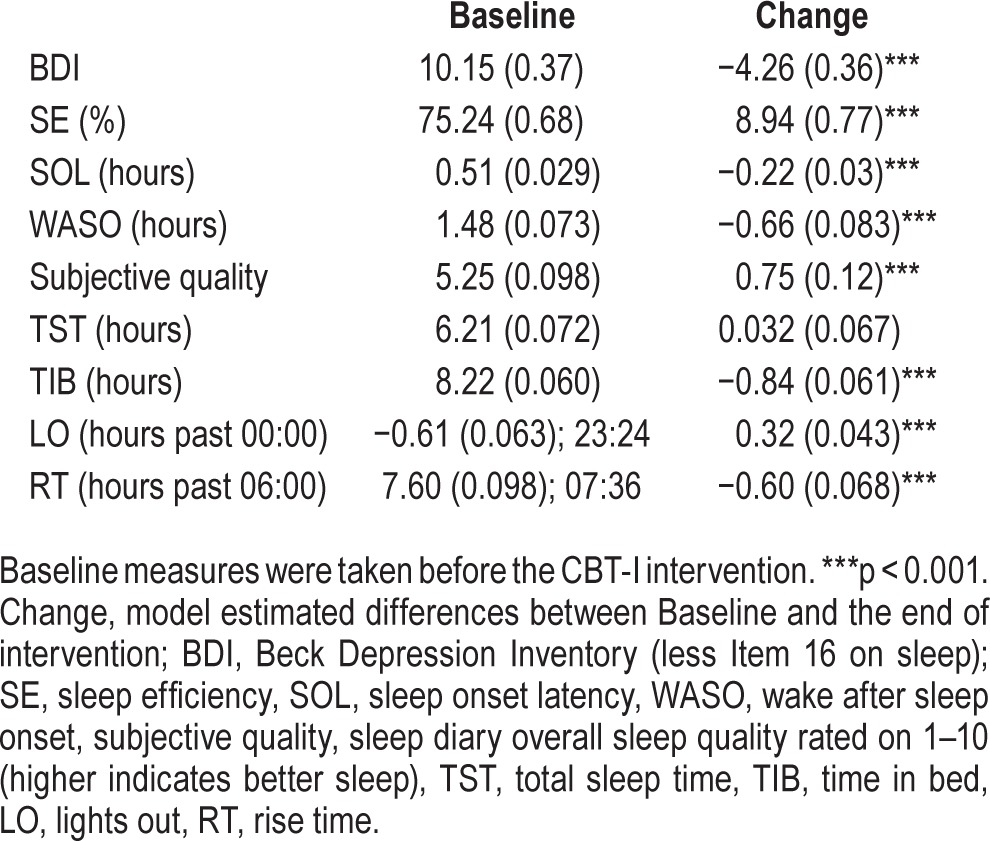

Descriptive statistics of Baseline and End SE and total BDI scores less the item on sleep are presented in Table 2. The multilevel model testing the change in SE in the intent-to-treat sample indicated that there was a statistically significant increase in SE (p < 0.001), with an average increase of 8.9% (Std Err = 1.09). This suggests that overall SE improved significantly from Baseline to the end of the group program. The variability of change in SE over time, defined by the slope of SE, was also significant, σ2 (Std Err) = 132.08 (14.16), p < 0.001, suggesting significant individual differences in the changes in SE. To help interpret the change in SE, changes in sleep parameters that are related to SE were also evaluated using the same statistical method as previously described for SE, and results were as follows: (a) SOL and WASO decreased significantly by an average of 13.2 and 39.6 min, respectively, consistent with the significantly improved overall subjective sleep quality; (b) TIB deceased significantly by an average of 50.4 min, while TST did not change significantly; (c) LO delayed while RT advanced significantly by an average of 19.2 and 36 min, respectively. Model estimated baseline and changes in these variables are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model estimated mean (standard error) for baseline and changes in depressive symptoms and sleep diary variables.

The distribution of BDI scores at Baseline were as follows: 42.4% mild, 16.6% moderate, and 4.4% severe depressive symptoms; these decreased to 28.3%, 5.5%, and 0.8% respectively at End. The LDS used to test changes in BDI suggested that there were significant changes in BDI scores less the sleep item (square root transformed) and its variance (p < 0.001). This suggests that the total scores of BDI (less the sleep item) decreased significantly by an average of 4.26 points from Baseline to the end of treatment, and individual differences in this change were also significant.

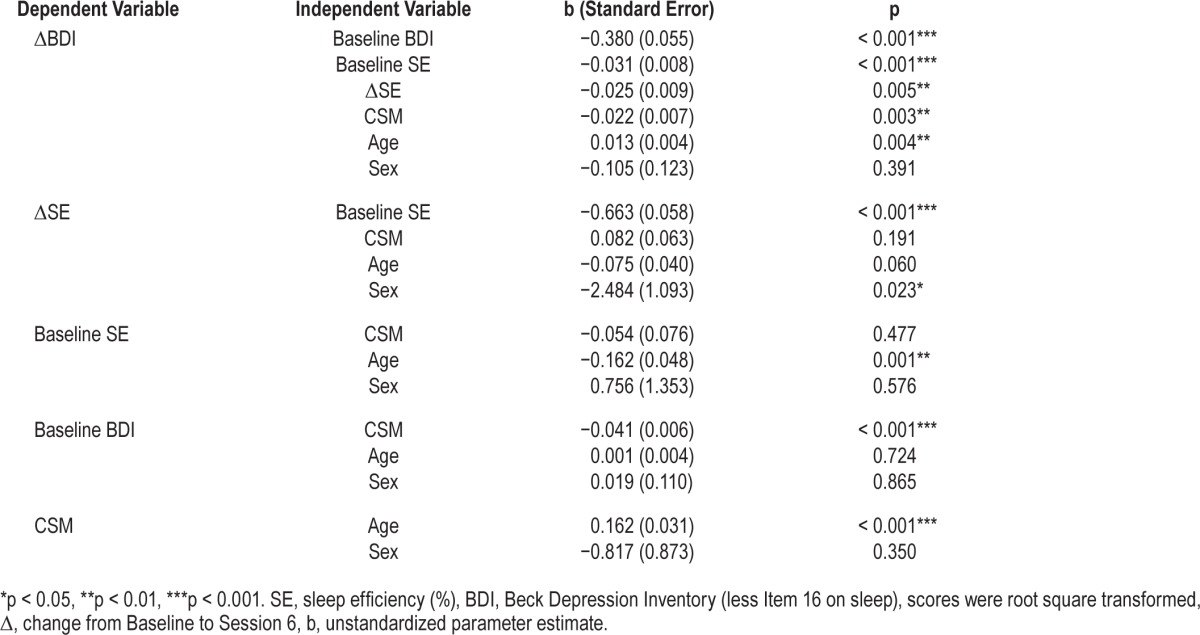

Primary Analyses: Sleep Efficiency, Chronotype, and Depressive Symptom

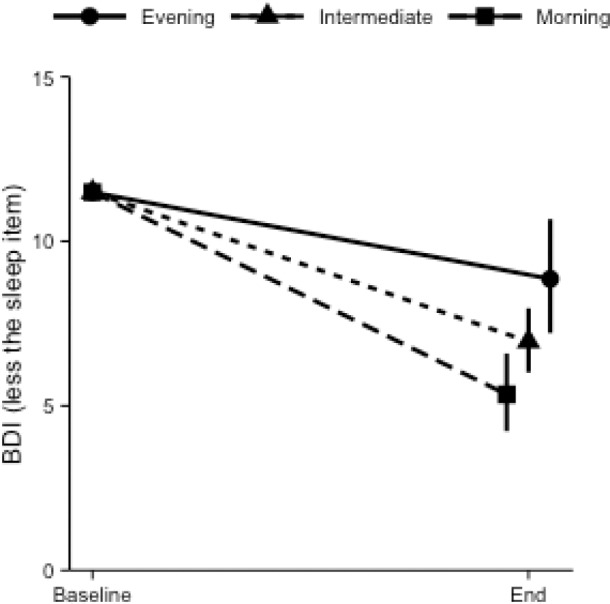

Mean CSM score was 35.70 (SD 9.13), with 8.6% evening type, 67.8% intermediate type, and 23.6% morning type. Controlling for age and sex, the model evaluating the contributions of CSM and SE on BDI showed that greater evening preference (p < 0.01), less improvements in SE (p < 0.01), as well as lower Baseline BDI (p < 0.001) and SE (p < 0.001) each significantly and uniquely predicted less reduction in BDI from Baseline to Session 6. These results are summarized in Table 3. Among those who scored moderate to severe depressive symptoms at Baseline (BDI scores 19–52 in this study), every 5% increase in SE (i.e., increased sleep quality) and every 5-point increase on CSM (i.e., less eveningness), was associated with an average of 1.38- and 1.43-point decrease in BDI (less the sleep item) scores, respectively. Figure 1 highlights age- and sex-adjusted effect of CSM on changes in BDI (less the sleep item) for Evening, Intermediate, and Morning types when baseline BDI and SE were held at their respective means. Therefore, the primary hypotheses of this study were confirmed.

Table 3.

Results of simultaneous regressions on the relationships among sleep efficiency, depressive symptoms, and CSM.

Figure 1. Age and sex adjusted changes in BDI score (less the sleep item) from Baseline to End with 95% confidence intervals for individuals who fell within the Evening, Intermediate, and Morning type based on the CSM.

Baseline BDI and SE were held at respective sample means.

The model tested also indicates that controlling for age and sex: (a) lower Baseline SE was associated with significantly greater increase in SE (p < 0.001), but evening preference did not predict change in SE (p > 0.05); (b) at Baseline, greater evening preference was associated with significantly higher BDI (p < 0.001). Older age was associated with stronger morning preference (p < 0.001), lower Baseline SE (p < 0.01), and less improvement in SE (p = 0.06). Age was not significantly associated with Baseline BDI, but older age significantly predicted less improvement in BDI (p < 0.01). Being female was associated with less improvement in SE (p < 0.05); however, the associations between sex and other variables were not significant.

DISCUSSION

In a large outpatient insomnia sample, both sleep and mood improved significantly after group CBT-I intervention. A novel aspect of the current study is its focus on predictors of the mood-improving effect of CBT-I: after controlling for baseline SE, BDI, age and sex, stronger evening preference (lower MCS scores) and less improvement in SE independently predicted less reduction in depressive symptom severity following CBT-I. To the extent that the morningness-eveningness trait can be regarded as a reflection of the circadian phase, findings from this study suggest that sleep and circadian factors might play distinctive roles in the maintenance of depressive symptoms in insomnia patients. Other predictors of less reduction in depressive symptom severity included lower baseline depressive symptoms, lower baseline SE, and older age. This suggests that those with higher depressive symptoms might particularly benefit from the mood-improving effects of CBT-I, while those with poorer sleep and older age might benefits less.

In this study, stronger evening preference was not only associated with higher depressive symptom severity at baseline, but also with lower reduction in depressive symptom severity after group CBT-I. This is consistent with previous findings that documented associations between eveningness and depressive symptomology,12,14 as well as eveningness and lower likelihood of remission from depression over time.15 Several possible mechanisms may underlie the association between stronger evening preference and more persistent depressive symptoms after CBT-I. First, evening preference has been associated with a number of known risk factors for depression, for example, neuroticism,22 substance use,23 and dysfunctional cognition such as dysfunctional beliefs about sleep.13 Neuroticism and substance use are not addressed in CBT-I. Although CBT-I therapeutically targets sleep-related cognitions, it does not directly address non-sleep related cognitions that constitute cognitive vulnerability for depression and sleep-related mood problems,24 such as negatively biased thoughts and beliefs about the world, self, and the future.25 Second, larger inter-individual differences in circadian phase and phase angle of entrainment have been reported in individuals with late sleep-wake timing compared to those with relatively earlier sleep-wake timing.26 This finding suggests that a greater proportion of circadian phase misalignment would be evident in individuals with late sleep/wake timing, and by implication, those with evening preference. Circadian misalignment is associated with mood disturbances.27 Although chronotype is often assessed in CBT-I, circadian phase is not systematically assessed in clinical settings, including in the present study. The real-life implementation of CBT-I in the current study did consider chronotype when selecting a time in bed window for sleep restriction therapy, but it did not include treatment component for circadian realignment. Third, evening preference has been associated with significantly greater sleep/wake variability28 and greater discrepancies between socially preferred and biologically determined sleep/wake schedules (i.e., social jet lag).29 Although CBT-I aims to, and based on follow-up analyses (variability analysis was conducted using a purpose-built Bayesian framework.30), resulted in significantly reduced BT and RT intra-individual variability in this sample (both p < 0.01), more variable RT (but not BT) remained to be associated with more evening preference (p = 0.052). Variable sleep/ wake patterns could contribute to restriction of sleep duration and/or displacement of sleep timing, both of which have been associated with mood problems.31,32 Finally, there is evidence for the role of the circadian system in the genetic susceptibility to major depression.33 Circadian timing mechanisms may therefore, in some cases, underlie both evening preference and depression symptomology.

As expected, following CBT-I, sleep efficiency improved significantly by an average of approximately 9%, which is comparable magnitude to that estimated in a review of randomized controlled CBT-I trials.1 Post hoc analyses in this study showed that although SOL and WASO decreased significantly, changes in TST were minimal. This pattern of change in sleep parameters is common in CBT-I, possibly because sleep restriction therapy involves an initial abrupt decrease, and subsequent slow and gradual increase of TIB. Change in TST usually follows a similar pattern, decreasing initially and increasing slowly later. In addition to improving sleep, by spending less time in bed, more time is available for engaging in wake activities. In fact, to promote and facilitate adherence to the recommended restriction of time spent in bed, clinicians delivering CBT-I often recommend and discuss engagement in wake activities (e.g., taking a walk outside, scheduling an appointment with a friend).34 Increase in wake activities is a form of behavioral activation, which has been found to be an efficacious treatment for adults with major depression.35

In addition to predictors of depressive symptom reduction, this study also examined predictors of increase in SE. Chrono-type did not emerge as a predictor of either baseline or changes in SE. This suggests that all chronotypes could benefit from the sleep-improving effect of CBT-I, even though patients with evening tendency were less likely to benefit from the positive impact of CBT-I on depressive symptoms. In contrast, lower baseline SE was associated with significantly greater improvement in SE. This suggests that those with poorer sleep quality might be more likely to experience improvement in sleep with CBT-I. It is, however, also possible that regression to the mean might have contributed to this association. That said, the fact that in this study, older age was associated with significantly lower SE at baseline yet less improvement in SE suggests that regression to the mean does not fully explain the association between lower SE at baseline and greater improvement in SE. It is also to be noted that there are mixed findings in the literature regarding the relationship between age and responses to CBT-I. While this and other studies found less increase in SE among older patients after CBT-I,36 some others found that older adults (≥ 60) had greater reduction in wake time compared to younger (≤ 44) adults at 1-year follow-up.37

Limitations and Strengths

Findings of this study need to be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, due to the lack of a control condition in this clinical setting, factors other than the CBT-I intervention might have also contributed to changes in sleep efficiency and depressive symptoms. In addition, information regarding concurrent treatments for depression such as antidepressant medications and psychotherapy was not systematically collected, and therefore it is not possible to rule out the possibility that those with greater morning preference (also greater reduction in depressive symptoms severity) were more likely to be receiving concomitant treatments for depression. Second, analysis excluded those who dropped out from treatment very early, before receiving recommendations to follow stimulus control or sleep restriction therapy, two core components of CBT-I. Therefore findings might not generalize to those who dropped out early. Also, the current sample consisted of patients seeking treatment for insomnia in a sleep clinic, and might not be generalizable to patients with a major depressive disorder seeking treatment for depression. In addition, information regarding the presence and treatment of comorbid sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea) is not available in the current dataset, and therefore cannot be controlled for. Finally, this study assessed morningness-eveningness rather than circadian phase. Although morningness-eveningness is strongly associated with circadian phase, the trait is also influenced by the homeostatic sleep system38; therefore direct associations between circadian phase and changes in depressive symptoms are premature based on these data.

This is the first study that examined the distinctive roles of sleep improvements and morningness-eveningness on changes of depressive symptoms following CBT-I. A strength of this study is the nature of the population sampled, which consisted of patients seeking treatment for insomnia in a sleep clinic, and results are likely to have good generalizability. An additional strength is the use of all available daily data through appropriate statistical methods that accounted for missing data that commonly occur in a longitudinal design.

Clinical Implications and Conclusions

The prevalence of depressive symptoms among patients seeking treatment for insomnia is high (63% in the current sample). This study suggested that despite the mood-improving benefits of CBT-I, depressive symptoms might remain elevated, especially those with greater evening chronotype, less improvement in SE, poorer sleep at baseline, and older age. It is important to recognize that appropriate management of insomnia comorbid with depression should involve the combination of CBT-I with depression treatment. Antidepressant medication and behavioral activation therapy,39 for example, can be easily integrated into CBT-I. Our findings suggest that individuals with stronger evening preference might benefit from additionally included circadian interventions. For example, timed light therapy40 and melatonergic antidepressants41 have been shown to be efficacious in reducing depressive symptoms, and can be combined relatively easily with CBT-I. Assessment of chronotype prior to CBT-I, and in the future, easier and more accurate assessment of circadian phase, may identify who needs this additional component and thus enhance clinical care. Finally, CBT-I was effective in improving sleep quality regardless of chronotype. For individuals whose sleep remains disturbed, pharmacotherapy for insomnia and/or individual (one-on-one) CBT-I should be trialed to address persistent insomnia symptoms.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This work was supported by the Helen Bearpark Scholarship from the Austral-asian Sleep Association, and Research Higher Degree Career Development from the University of Melbourne. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. There is no off-label or investigational use in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Christine Celio, Jennifer Huang, Mary Huang, Sachiko Ito, Robin Okada, and Anna Packard for providing assistance with data management. International travels related to this work were funded by the Helen Bearpark Scholarship awarded by the Australasian Sleep Association, and Research Higher Degree Career Development Award by the University of Melbourne. The authors also thank Joshua F. Wiley for statistical advice.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- CBT-I

cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- CSM

Composite Scale of Morningness

- IRB

Internal Review Board

- LDS

latent difference score

- LO

light out

- RT

rise-time

- SE

sleep efficiency

- SE

sleep efficiency

- SEM

structural equation modeling

- SOL

sleep onset latency

- TIB

time in bed

- TST

total sleep time

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

REFERENCES

- 1.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998-2004) Sleep. 2006;29:1398–414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2851–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manber R, Bernert RA, Suh S, Nowakowski S, Siebern AT, Ong JC. CBT for insomnia in patients with high and low depressive symptom severity: adherence and clinical outcomes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:645–52. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:489–95. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie SR, Wilson KG, Curran D. Clinical significance and predictors of treatment response to cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia secondary to chronic pain. J Behav Med. 2002;25:135–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1014832720903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantino MJ, Manber R, Ong J, Kuo TF, Huang JS, Arnow BA. Patient expectations and therapeutic alliance as predictors of outcome in group cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5:210–28. doi: 10.1080/15402000701263932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey AG. Sleep and circadian functioning: critical mechanisms in the mood disorders? Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:297–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. 2013;36:1059–68. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dew MA, Reynolds CF, Houck PR, et al. Temporal profiles of the course of depression during treatment. Predictors of pathways toward recovery in the elderly. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1016–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, Tu X, Kupfer DJ. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord. 1997;42:209–12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czeisler CA, Weitzman E, Moore-Ede MC, Zimmerman JC, Knauer RS. Human sleep: its duration and organization depend on its circadian phase. Science. 1980;210:1264–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7434029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hidalgo MP, Caumo W, Posser M, Coccaro SB, Camozzato AL, Chaves MLF. Relationship between depressive mood and chronotype in healthy subjects. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:283–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong JC, Huang JS, Kuo TF, Manber R. Characteristics of insomniacs with self-reported morning and evening chronotypes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:289–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaspar-Barba E, Calati R, Cruz-Fuentes CS, et al. Depressive symptomatology is influenced by chronotypes. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan JW, Lam SP, Li SX, et al. Eveningness and insomnia: independent risk factors of nonremission in major depressive disorder. Sleep. 2014;37:911–7. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong JC, Kuo TF, Manber R. Who is at risk for dropout from group cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia? J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith CS, Reilly C, Midkiff K. Evaluation of three circadian rhythm questionnaires with suggestions for an improved measure of morningness. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74:728–38. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.74.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McArdle JJ. Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta PD, Neale MC. People are variables too: multilevel structural equations modeling. Psychol Methods. 2005;10:259–84. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enders KC, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling. 2001;8:430–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonetti L, Fabbri M, Natale V. Relationship between circadian typology and big five personality domains. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:337–47. doi: 10.1080/07420520902750995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prat G, Adan A. Influence of circadian typology on drug consumption, hazardous alcohol use, and hangover symptoms. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28:248–57. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.553018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bei B, Wiley JF, Allen NB, Trinder J. A cognitive vulnerability model on sleep and mood in adolescents under naturalistically restricted and extended sleep opportunities. Sleep. 2015;38:453–61. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scher CD, Scher CD, Ingram RE, Ingram RE, Segal ZV. Cognitive reactivity and vulnerability: empirical evaluation of construct activation and cognitive diatheses in unipolar depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sletten TL, Vincenzi S, Redman JR, Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SMW. Timing of sleep and its relationship with the endogenous melatonin rhythm. Front Neurol. 2010;1:137. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2010.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emens J, Lewy A, Kinzie JM, Arntz D, Rough J. Circadian misalignment in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168:259–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suh S, Nowakowski S, Bernert RA, et al. Clinical significance of night-to-night sleep variability in insomnia. Sleep Med. 2012;13:469–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23:497–509. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiley JF, Bei B, Trinder J, Manber R. Variability as a predictor: a Bayesian variability model for small samples and few repeated measures. arXiv preprint. 2014;arXiv 1411.2961. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum KT, Desai A, Field J, Miller LE, Rausch J, Beebe DW. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:180–90. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levandovski R, Dantas G, Fernandes LC, et al. Depression scores associate with chronotype and social jetlag in a rural population. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28:771–8. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.602445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soria V, Martínez-Amorós È, Escaramís G, et al. Differential association of circadian genes with mood disorders: CRY1 and NPAS2 are associated with unipolar major depression and CLOCK and VIP with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1279–89. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:658–70. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gagné A, Morin CM. Predicting treatment response in older adults with insomnia. J Clin Gerontol. 2001;7:131–43. [Google Scholar]

- 37.A Espie C, Inglis SJ, Tessier S, Harvey L. The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic insomnia: implementation and evaluation of a sleep clinic in general medical practice. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mongrain V, Carrier J, Dumont M. Circadian and homeostatic sleep regulation in morningness-eveningness. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:162–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Even C, Schröder CM, Friedman S, Rouillon F. Efficacy of light therapy in nonseasonal depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hickie IB, Rogers NL. Novel melatonin-based therapies: potential advances in the treatment of major depression. Lancet. 2011;378:621–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]