Abstract

Solitary unilateral lung cyst is an unusual finding in preterm infants. It may be difficult to distinguish acquired from congenital lung cysts clinically. The definitive diagnosis is histological; however, CT scan of the chest is a useful diagnostic tool. We present an extremely preterm infant with solitary lung cyst and background chronic lung disease. The initial chest x-rays showed solitary right lung cyst. At 6 weeks he required an escalation of ventilator support coupled with x-ray evidence of increased size of the cyst. CT scan confirmed large solitary cyst of the right lower lobe with evidence of compression and mediastinal shift, suspicious of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. The cyst was surgically removed in view of clinical deterioration. However, histology showed persistent pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PPIE). This case illustrates that in the context of prematurity PPIE can present as a solitary lung cyst and may require surgery.

Background

Solitary lung cyst is an unusual finding in infants and especially so in preterm infants.1–3 Nowadays, most congenital cystic lesions are diagnosed antenatally with routine anomaly ultrasound scans performed around 20 weeks of gestation. However, cysts diagnosed after birth could either be acquired or congenital and clinical distinction between the two may be difficult. The differential diagnosis includes congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM), congenital lung sequestration, acquired lesions such as persistent pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PPIE), etc.

The definitive diagnosis is therefore histological; however, surgical resection of these lung cysts is controversial and many advocate a conservative medical approach. On the other hand, CT scan of the chest could be a useful diagnostic tool in the postnatal period.1

Localised PPIE has rarely been reported in preterm infants. We report a case of an unstable patient with PPIE successfully treated by lobectomy as a form of conservative surgical approach.

Case presentation

Birth details

We present an extremely preterm infant who was born spontaneously at 23+4 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 680 g. He was the recipient of twin of a twin–twin transfusion syndrome which was treated with laser therapy, his other twin was stillborn. He was exposed to antenatal steroids and received exogenous surfactant after delivery. He was stabilised at birth.

Early neonatal course

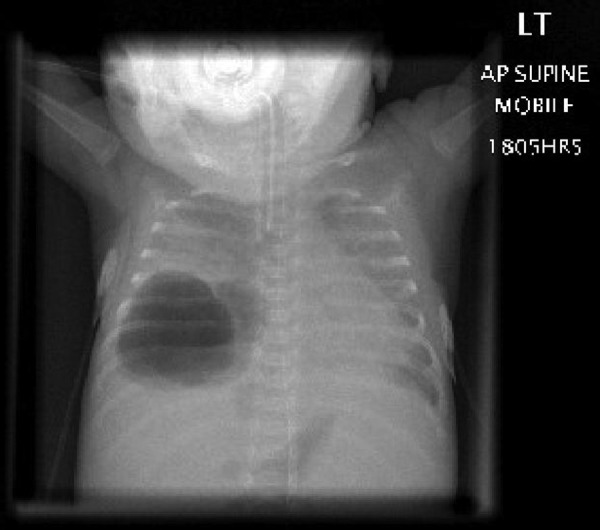

This infant had a stormy early neonatal course and remained on mechanical ventilation for the initial 2 months of life. During that period he had episodes of large pulmonary haemorrhage, sepsis and necrotising enterocolitis. He also underwent surgical ligation of a 5 mm-sized patent ductus arteriosus at the age of 2 weeks. Initial chest radiographs during the first few days of life showed features of hyaline membrane disease but also a large lung cyst in the lower right lung (figure 1). His lung disease was regarded as severe as he remained on mechanical ventilation and at 5 weeks of age was on high peak inspiratory pressure of 30 cm H2O and positive end expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O and 60% supplemental oxygen.

Figure 1.

x-Ray chest showing large lung cyst in the right lower lung.

At 6 weeks of age he had an acute respiratory deterioration which was attributed to the enlargement of lung cyst with lung compression.

Investigations and treatment of lung cyst

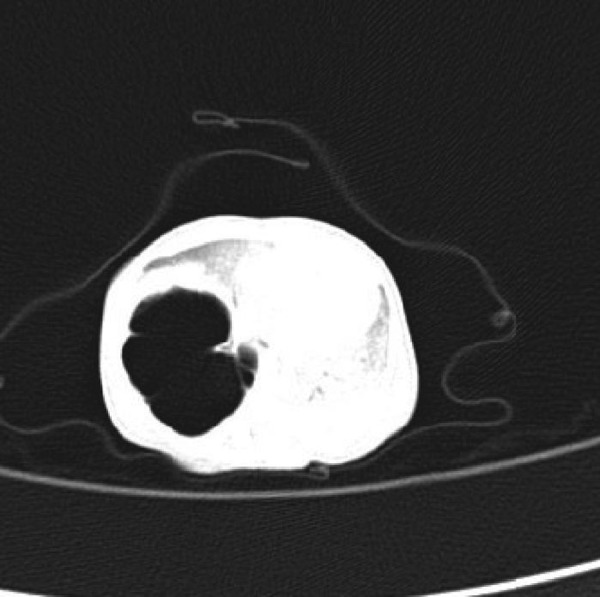

CT scan of the chest showed a 34×33 mm cyst in the right lower lobe with thick septations and a clear rim. There was also evidence of compression and mediastinal shift (figure 2).

Figure 2.

CT chest showing 34×33 mm cyst in the right lower lobe with thick septations and a clear rim. There was also evidence of compression and mediastinal shift.

The cyst was surgically removed in view of clinical deterioration and difficulty in ventilation due to increase in the size of the cyst. However, histology showed PPIE.

Subsequent respiratory course

There was appreciable improvement in the respiratory status with reducing ventilator requirements seen in the immediate postlobectomy period. However, he remained dependent on non-invasive respiratory support as a consequence of severe broncho-pulmonary dysplasia (BPD). He received postnatal steroid therapy for BPD and was considered to have steroid-responsive BPD and was discharged home on small dose of steroids. In addition, it was difficult to wean him off positive pressure support and his oxygen requirements remained substantial. At the age of 2 weeks post-term he was investigated for clinical heart failure and echocardiography showed features of pulmonary hypertension. This was treated with a course of sildenafil and later with addition of Bosentan (an endothelin-1 receptor antagonist) with the aim of improving haemodynamics and help weaning respiratory support. Simultaneously, sildenafil and steroids were gradually weaned down. Also he gradually came off respiratory support and was discharged home 2 months post-term and at postnatal age of 9 months. Pulmonary hypertension persisted and he needed long-term treatment after discharge.

Outcome and follow-up

He is currently 3.5 years old and is doing well. He is not on any respiratory support and has no respiratory problems. He has Harrison sulcus. He is feeding well and has percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) but can take solids orally as well. He is thriving well and is on 25th centile for weight and 9th centile for height.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that PPIE can complicate underlying bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants.

PPIE is a rare condition that occurs in both preterm and term infants. It is characterised by abnormal accumulation of air in the pulmonary interstitium, due to disruption of the basement membrane.

The lesion usually presents in preterm newborns as a complication of respiratory distress syndrome and/or assisted ventilation, though less frequently in aspiration. Occasionally, PPIE may occur spontaneously in infants with no underlying pulmonary disease.

It is associated with positive pressure ventilation, high peak pressures and malpositioned endotracheal tubes.4 PPIE can complicate surgery in neonates associated with severe pulmonary hypoplasia and requiring ventilation such as after correction of congenital diaphragmatic hernia and postlobectomy in a larger congenital cystic lung lesion. It is commonly associated with a pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum.

Incidence of PPIE has decreased with the increasing use of surfactant and newer ventilatory strategies.

Clinical signs include respiratory acidosis and hypoxaemia in a severely ill infant. Localised PPIE may resolve spontaneously or may persist for several weeks.

The mortality from diffuse PPIE is high, but the studies reporting this predate routine use of antenatal steroids and surfactant.

Infants with PPIE and weighing less than 1000 g are at significant risk of mortality and associated morbidity of PPIE. The incidence of CLD following PPIE has increased.

Persistence of PIE may be diffuse or localised. Localised PPIE usually presents as multiple cysts 0.3–3 cm in one or more lobes of the lung.2

It is important for radiologists to consider localised PPIE in the differential diagnosis of cystic lung lesions in preterm infants, even in the absence of mechanical ventilation.

The characteristic CT scan appearance of PPIE which include extra-alveolar air accumulation, central lines and dots surrounded by radiolucency1 may be used to differentiate it from other congenital cystic lesions that may present similarly. In cases where there is uncertainty; CT imaging may be useful in making the correct diagnosis.5

The management of infants suffering from diffuse PPIE involves multidisciplinary input (neonatologist, respiratory physician, thoracic surgeon, radiologist, pathologist, etc). It varies according to severity and stability of the patient, being either conservative treatment or aggressive surgical treatment by pneumonectomy.

Although conservative management is accepted as the initial form of management in most cases, a review of the published literature found that a significant proportion of localised PPIE cases eventually underwent surgical resection.3

Learning points.

This case illustrates that in the context of prematurity, PPIE can present as a solitary lung cyst and it may require surgical removal.

The characteristic CT scan appearance of PPIE may be useful in differentiating it from other congenital cystic lesions.

Multidisciplinary team work is essential in managing infant with PPIE.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Donnelly LF, Lucaya J, Ozelame V, et al. CT findings and temporal course of persistent pulmonary interstitial emphysema in neonates: multiinstitutional study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003:180: 1129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MC, Drut RM, Drut R. Solitary unilocular cyst of the lung with features of persistent interstitial pulmonary emphysema: report of four cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol 1999;2:531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jassal MS, Benson JE, Mogayzel PJ. Spontaneous resolution of diffuse persistent pulmonary interstitial emphysema. Source Pediatr Pulmonol 2008;43:615–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart SM, McNair M, Gamsu HR, et al. Pulmonary interstitial emphysema in very low birth weight infants. Arch Dis child 1983;58:612–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berk DR, Varich LJ. Localized persistent pulmonary interstitial emphysema in a preterm infant in the absence of mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Radiol 2005;35:1243–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]