Abstract

Background

Genetic variation accounts for approximately 30% of blood pressure (BP) variability but most of that variability hasn't been attributed to specific variants. Interactions between genes and BP-associated factors may explain some ‘missing heritability.’ Cigarette smoking increases BP after short-term exposure and decreases BP with longer exposure. Gene-smoking interactions have discovered novel BP loci, but the contribution of smoking status and intensity to gene discovery is unknown.

Methods

We analyzed gene-smoking intensity interactions for association with systolic BP (SBP) in three subgroups from the Framingham Heart Study: current smokers only (N = 1,057), current and former smokers (‘ever smokers’, N = 3,374), and all subjects (N = 6,710). We used three smoking intensity variables defined at cutoffs of 10, 15, and 20 cigarettes per day (CPD). We evaluated the 1 degree-of-freedom (df) interaction and 2df joint test using generalized estimating equations.

Results

Analysis of current smokers using a CPD cutoff of 10 produced two loci associated with SBP. The rs9399633 minor allele was associated with increased SBP (5 mmHg) in heavy smokers (CPD>10) but decreased SBP (7 mmHg) in light smokers (CPD≤10). The rs11717948 minor allele was associated with decreased SBP (8 mmHg) in light smokers but decreased SBP (2 mmHg) in heavy smokers. Across all nine analyses, 19 additional loci reached p < 1×10−6.

Discussion

Analysis of current smokers may have the highest power to detect gene-smoking interactions, despite the reduced sample size. Associations of loci near SASH1 and KLHL6/KLHL24 with SBP may be modulated by tobacco smoking.

Keywords: Cardiovascular genetics, gene interactions, smoking, blood pressure

INTRODUCTION

High blood pressure (BP) is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and was the single biggest health burden globally in 2010 (Lim, SS et al. 2012). Although the heritability of BP is estimated to be approximately 30%, the specific genes and variants responsible have proven elusive. Genome-wide association studies have identified dozens of variants associated with BP, but they collectively explain less than 3% of BP variability (Ehret, GB 2010). Among the factors hypothesized to contribute to this ‘missing heritability’ are interactions between genes and other clinical factors (Manolio, TA et al. 2009) known to influence BP, including age (Shi, G et al. 2009), sex (Ramirez-Lorca, R et al. 2007), BMI (Ramirez-Lorca, R et al. 2007), alcohol consumption (Simino, J et al. 2013), and diet (Zhang, RR et al. 2013).

Cigarette smoking is an environmental exposure that is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease as well as a variety of other diseases including cancer and lung disease. Smoking has long been known to influence BP directly (Benowitz, NL et al. 1984) and is recently receiving attention for its role in modifying the influence of genetic variants on BP (Sung, YJ et al. 2014). The effects of smoking on BP are complex; epidemiologic studies have shown acute increases in BP but decreased BP with longer tobacco exposure (Green, MS et al. 1986).

Given the influence of tobacco smoking on BP, gene-smoking interactions may enable the detection of novel BP-associated variants. However, the complexity of the relationship between smoking and BP raises questions regarding the methods for investigating gene-smoking interactions that are most likely to contribute to novel gene discovery. In this study, we examined gene-smoking interactions by models that categorized subjects by two different exposure metrics: smoking status, with subjects self-identifying as current smokers, former smokers, or never smokers; and smoking intensity, characterized as the reported number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD). To investigate the influence these variables have on gene discovery, we performed a genome-wide analysis of gene-smoking interactions in three population subgroups (current smokers only, current and former smokers, and all subjects) defining dichotomous smoking intensity variables based on three different CPD cutoffs (> 10, > 15, and > 20 CPD).

METHODS

Subjects

The analysis used data from the Framingham SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000342.v12.p9). The Framingham Heart Study is a longitudinal study comprising three Caucasian cohorts: the Original cohort, recruited in 1948; the Offspring cohort, recruited in 1971 comprised of the offspring of the Original cohort and their spouses and children; and the Third Generation cohort, recruited in 2002 and consisting of the biological and adopted offspring of the Offspring cohort. The current study analyzed data from the lone clinic visit of the Third Generation cohort as well as the Original cohort visit and Offspring cohort visit most closely matching the date of that visit.

All subjects analyzed had non-missing genotype and imputed genotype data and complete data for SBP, cigarettes per day (CPD), age, sex, and anti-hypertension medication use. Three sets of subjects were analyzed. The All Subjects sample (N = 6,710) consisted of all subjects with complete data regardless of smoking status. The Ever Smokers sample (N = 3,374) consisted of subjects who were current or former smokers but excluded those who had never smoked. Finally, the Current Smokers sample (N = 1,057) consisted only of current smokers. Descriptive statistics for these samples are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics of analysis cohorts.

| All Subjects | Ever Smokers | Current Smokers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 6,710 | 3,374 | 1,057 |

| CPD10, % (n) | 32.7 (2,192) | 65.0 (2,192) | 65.1 (688) |

| CPD15, % (n) | 27.8 (1,868) | 55.4 (1,868) | 51.4 (543) |

| CPD20, % (n) | 10.6 (710) | 21.0 (710) | 15.6 (165) |

| Never Smokers, % (n) | 49.7 (3,336) | NA | NA |

| Age, years | 49.1 ± 13.5 | 51.6 ± 12.9 | 46.0 ± 12.2 |

| Male, % | 46.5 (3,123) | 47.0 (1,586) | 47.9 (506) |

| Taking Anti-hypertensive meds, % | 19.1 (1,283) | 22.4 (757) | 13.8 (146) |

| SBP, mm Hg | 123 ± 19 | 125 ± 20 | 121 ± 18 |

Data presented as % (n) or means ± standard deviation

Phenotypes and Genotypes

The analysis phenotype was the average of three systolic blood pressure (SBP) readings, (one taken by a nurse/technician and two taken by a physician). In subjects taking anti-hypertensive medication, the SBP value was adjusted by adding 15 mmHg.

Three dichotomous smoking covariates were derived from the continuous CPD data using different CPD cutoffs: CPD10, CPD15, and CPD20. Subjects have a dichotomous covariate value of 1 if their CPD value is greater than the cutoff. For example, CPD10 has a value of 1 when CPD > 10. For both the All Subjects and Ever Smokers samples, dichotomous CPD covariates were derived in former smokers using the reported average CPD value during the time they were smoking.

Genotyping was performed on the GeneChip Human Mapping 500K Array Set (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) which assays 487,998 SNPs. A total of 2.5 million SNPs were imputed based on HapMap data using MACH (Li, Y et al. 2010). For all analyses, SNPs were excluded for Mendelian errors, Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium (p ≤ 10−6), or poor imputation quality (r2 < 0.3). In addition, only SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 5% (calculated separately for each sample) were analyzed. The resulting SNP set included 2,144,020 SNPs in the All Subjects sample, 2,143,542 SNPs in the Ever Smokers sample, and 2,142,057 SNPs in the Current Smokers sample.

Analysis

The analyses were performed in a generalized estimating equations (GEE) framework using the R package geepack (available through CRAN). This approach uses robust standard errors which help reduce the inflation (and type I error) that can burden analysis of interactions (Voorman, A et al. 2011). The model we analyzed (using CPD10 in this example) is:

with each SNP coded using an additive model (0,1,2) and subjects clustered in families. Two tests were performed based on this model: a 1 degree-of-freedom (df) test of the SNP*CPD interactions (β5) and the 2 df joint test of the SNP main effect and SNP*CPD interaction (β 4, β5), and a genome-wide significance threshold of α=5×10−8 was used.

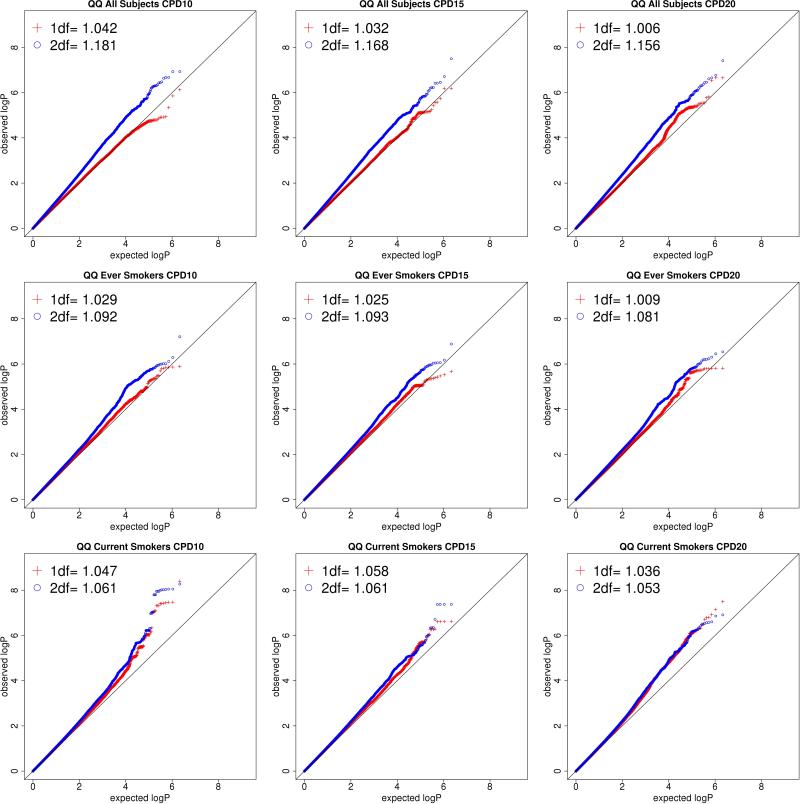

RESULTS

A total of nine analyses were performed, one for each combination of sample (All Subjects, Ever Smokers, and Current Smokers) and CPD cutoff (CPD10, CPD15, CPD20). One of the goals of this investigation was to determine which combination of the sample and CPD cutoff are promising for discovery in large consortia. For each analysis, the genomic inflation factor (λ, the ratio of the observed median χ2 value to the expected median χ2 value) for the 1df and 2df tests is shown in Table II (main effect λ values are shown in Supplementary Table I). Nine QQ plots showing both the 1df and the 2df tests are shown in Figure 1. The observed λ values are largely in line with the expectation for highly polygenic traits (Yang, J et al. 2011), although the 2df test shows evidence of moderate inflation, particularly in the All Subjects sample. This inflation is driven by the main effects (Supplementary Table I), while the corresponding 1df tests are well controlled (Table II).

Table II.

Genomic Inflation λ of the SNP*CPD interaction, 1df and 2df.

| Sample | 1df λ | 2df λ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPD10 | CPD15 | CPD20 | CPD10 | CPD15 | CPD20 | |

| All Subjects | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| Ever Smokers | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.08 |

| Current Smokers | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.05 |

Table II shows the genomic inflation λ value for the 1df test for each combination of sample and CPD cutoff.

Figure 1. QQ plots by sample and CPD cutoff.

Figure 1 shows the QQ plots for each of the 9 analyses with the indicated combination of sample composition and CPD covariate. The 1df test is shown in red and 2df test is shown in blue. The genomic control lambda values for both tests are inset. The majority of analyses are well controlled, showing modest inflation. The primary signal of interest (−log(P) > 7) is located in the analysis of the Current Smokers group using CPD10 and comes from both 1df and 2df tests.

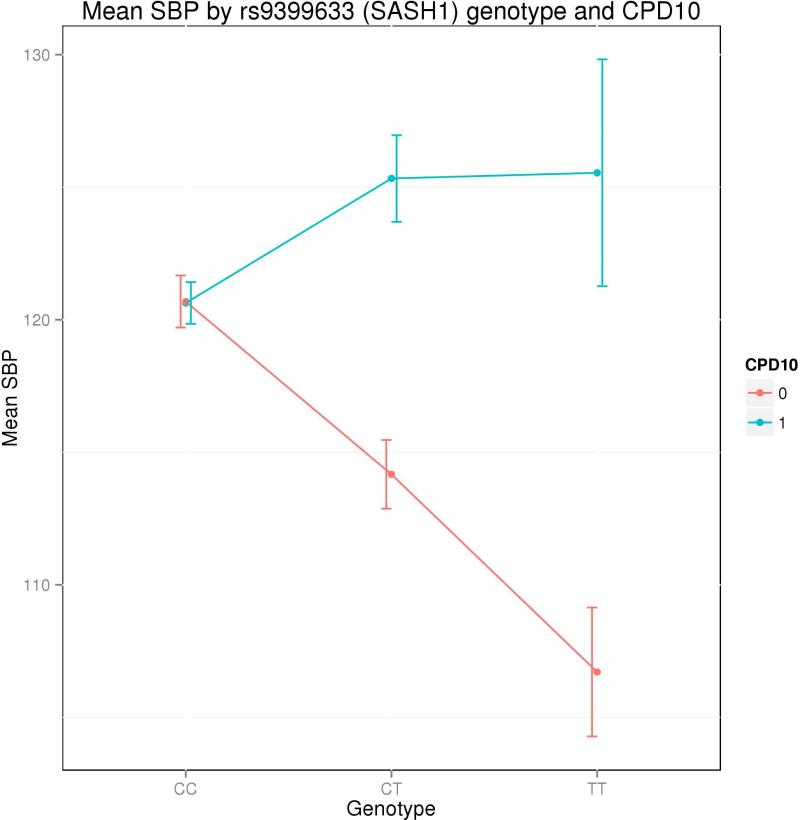

Across all nine analyses, two loci contained SNPs that reached genome-wide significance using p-values adjusted for genomic inflation (α = 5×10−8; Table III). Both loci were detected in the Current Smokers CPD10 analysis. For this analysis, both the 1df and 2df tests gave rise to a strong association signal (inflation-adjusted 1df: p = 1.0×10−8; 2df: p = 1.8×10−8) on chromosome 6 with multiple SNPs reaching genome-wide significance in a locus located 150 – 200 kb upstream of the nearest gene, SASH1. Among subjects who smoked ≤ 10 cigarettes per day, each C allele at the most significant SNP in this locus (rs9399633, MAF = 14.6%, Table III) was associated with an average SBP decrease of about 5 mmHg, while in subjects who smoked > 10 cigarettes per day, each C allele was associated with an average SBP increase of 5 mmHg (Figure 2).

Table III.

Significant Associations

| Sample | CPD cutoff | SNP | Major/minor allele | CHR | BP | MAF | BETA SNP | BETA INT | P SNPGC | P INTGC | P 2dfGC | Gene | Distance (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 10 | rs9399633 | C/T | 6 | 148062948 | 0.146 | 5.07 | −9.6 | 1.42E-06 | 1.00E-08 | 1.83E-08 | SASH1 | 149 |

| Current | 10 | rs1534774 | C/G | 6 | 148034416 | 0.121 | 5.53 | −9.8 | 4.06E-07 | 7.64E-08 | 2.94E-08 | SASH1 | 178 |

| Current | 10 | rs9390526 | T/C | 6 | 148030680 | 0.121 | −5.5 | 9.78 | 4.07E-07 | 7.72E-08 | 2.96E-08 | SASH1 | 181 |

| Current | 10 | rs1534775 | A/G | 6 | 148035906 | 0.121 | 5.53 | −9.8 | 4.10E-07 | 8.07E-08 | 3.06E-08 | SASH1 | 176 |

| Current | 10 | rs1358689 | T/C | 6 | 148012824 | 0.121 | −5.5 | 9.74 | 4.07E-07 | 8.54E-08 | 3.16E-08 | SASH1 | 199 |

| Current | 10 | rs9386204 | A/G | 6 | 148013180 | 0.121 | 5.54 | −9.7 | 4.06E-07 | 8.65E-08 | 3.19E-08 | SASH1 | 199 |

| Current | 10 | rs1404488 | G/A | 6 | 148038927 | 0.121 | −5.5 | 9.73 | 4.17E-07 | 8.90E-08 | 3.30E-08 | SASH1 | 173 |

| Current | 10 | rs1881827 | A/G | 6 | 148020538 | 0.121 | 5.53 | −9.7 | 4.06E-07 | 1.07E-07 | 3.66E-08 | SASH1 | 192 |

| Current | 10 | rs9377097 | A/G | 6 | 148019979 | 0.121 | 5.53 | −9.7 | 4.06E-07 | 1.07E-07 | 3.66E-08 | SASH1 | 192 |

| Current | 10 | rs1881826 | G/A | 6 | 148020622 | 0.121 | −5.5 | 9.66 | 4.07E-07 | 1.07E-07 | 3.66E-08 | SASH1 | 191 |

| Current | 10 | rs11717948 | G/A | 3 | 183591640 | 0.0547 | −9 | 7.04 | 1.47E-08 | 8.34E-03 | 5.03E-08* | KLHL6 KLHL24 |

36 |

| Current | 10 | rs9872196 | C/A | 3 | 183592150 | 0.0546 | −9.3 | 7.42 | 1.37E-08 | 7.08E-03 | 5.07E-08* | KLHL6 KLHL24 |

36 |

| Current | 10 | rs11706582 | T/C | 3 | 183591975 | 0.0552 | −9.2 | 7.24 | 1.46E-08 | 8.34E-03 | 5.09E-08* | KLHL6 KLHL24 |

36 |

Figure 2. Mean SBP by SASH1 genotype and CPD10 status in Current Smokers.

Figure 2 shows the average SBP for groups of subjects defined by their genotype at rs9399633 and their CPD10 status. Subjects with CPD ≤ 10 are shown in blue, and subjects with CPD > 10 are shown in red. Error bars indicate standard error for each mean SBP value.

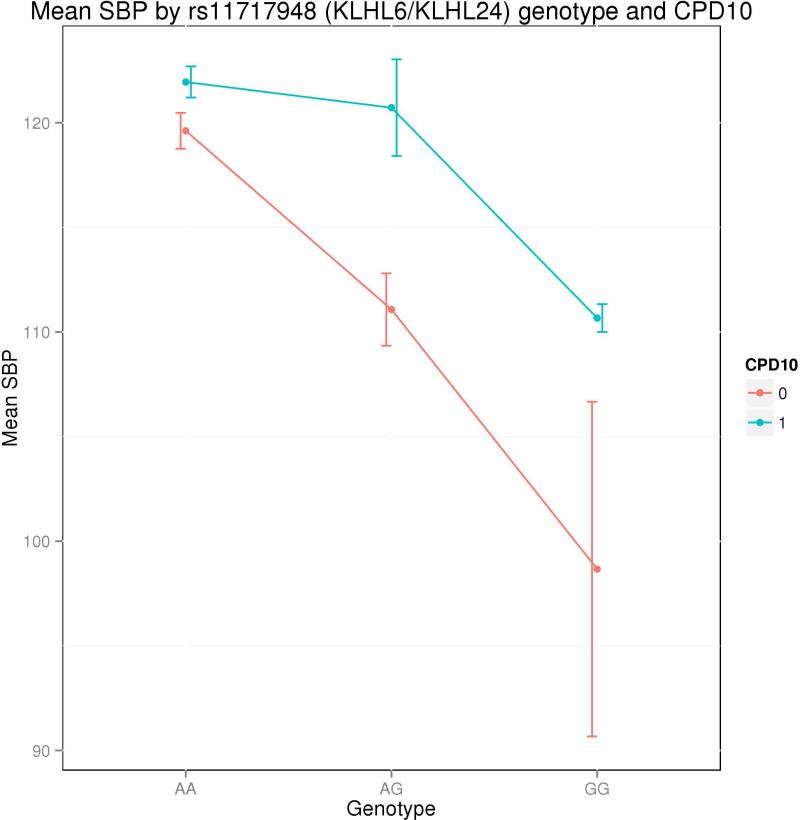

A second genome-wide significant locus was detected with the 2df test (inflation-adjusted p = 5.0×10−8) on chromosome 3, with KLHL6 and KLHL24 located about 40 kb on either side of the associated SNPs. Among subjects who smoked ≤ 10 cigarettes per day, each G allele at the most significant SNP in the locus (rs11717948 , MAF = 5.4%, Table III) was associated with an average SBP decrease of about 9 mmHg, while among subjects who smoked > 10 cigarettes per day, G alleles were associated with an average SBP decrease of only about 2 mmHg (Figure 3). These genome-wide significant association results are shown in Table III.

Figure 3. Mean SBP by KLHL6/KLHL24 genotype and CPD10 status.

Figure 2 shows the average SBP for groups of subjects defined by their genotype at rs11717948 and their CPD10 status. Subjects with CPD ≤ 10 are shown in blue, and subjects with CPD > 10 are shown in red. Error bars indicate standard error for each mean SBP value.

A total of 19 other loci across all analyses gave rise to suggestive associations (inflation-adjusted p < 10−6), with the majority (13) also identified from the analysis of the Current Smokers sample: one suggestive locus was detected using a CPD cutoff of 10, one locus was detected using a cutoff of 15, and 11 suggestive loci were detected using a cutoff of 20 (Table IV). Of the six suggestively associated loci detected in other samples, four were detected in the All Subjects sample (two from CPD15 and two from CPD20 analyses) and two were detected in the Ever Smokers sample (one from both CPD10 and CPD15 and one from CPD20 analyses, Table IV).

Table IV.

Suggestive Associations

| Sample | CPD cutoff | SNP | Non-coded/coded allele | CHR | BP | MAF | Beta Main | Beta 1df Intxn | P SNP Main (Genomic Control) | P 1df Intxn (Genomic Control) | P 2df Intxn (Genomic Control) | Gene | Distance(kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 15 | rs6916459 | A/C | 6 | 54734919 | 0.104 | −1.07 | 5.75 | 7.91E-02 | 9.58E-07 | 2.38E-05 | FAM83B | 112 |

| All | 15 | rs12662500 | G/C | 6 | 54730930 | 0.104 | 1.07 | −5.74 | 7.92E-02 | 9.64E-07 | 2.39E-05 | FAM83B | 116 |

| All | 15 | rs12469933 | T/G | 2 | 139266368 | 0.102 | −4.46 | 4.28 | 2.58E-07 | 4.59E-03 | 3.82E-07 | NXPH2/LRP1B | 486 |

| All | 20 | rs4761750 | G/C | 12 | 93928698 | 0.0742 | −2.11 | 12.7 | 2.42E-02 | 2.41E-07 | 6.60E-06 | CRADD | 33 |

| All | 20 | rs12372697 | A/G | 12 | 93935745 | 0.0742 | 2.1 | −12.7 | 2.43E-02 | 2.41E-07 | 6.61E-06 | CRADD | 40 |

| All | 20 | rs11107292 | A/G | 12 | 93946957 | 0.0742 | 2.1 | −12.8 | 2.48E-02 | 3.22E-07 | 8.14E-06 | CRADD | 51 |

| All | 20 | rs1229982 | T/G | 4 | 99322775 | 0.189 | 1.59 | 3.38 | 4.06E-04 | 6.79E-03 | 4.00E-07 | ADH1B | intron |

| Ever | 10 | rs2355654 | C/T | 14 | 49988369 | 0.36 | −3.95 | 1.54 | 9.59E-06 | 1.73E-01 | 2.56E-07 | C14orf182 | intron |

| Ever | 15 | rs2355654 | C/T | 14 | 49988369 | 0.36 | −3.73 | 1.42 | 6.68E-06 | 2.06E-01 | 5.16E-07 | C14orf182 | intron |

| Ever | 20 | rs12699566 | T/C | 7 | 13934836 | 0.269 | 0.421 | 6.75 | 5.60E-01 | 5.56E-06 | 9.31E-07 | ETV1 | intron |

| Current | 10 | rs6934331 | T/A | 6 | 148044773 | 0.132 | 4.96 | −9.12 | 5.50E-06 | 1.77E-07 | 2.60E-07 | SASH1 | 167 |

| Current | 10 | rs2328843 | C/T | 6 | 148047081 | 0.132 | −4.96 | 9.1 | 5.54E-06 | 1.85E-07 | 2.69E-07 | SASH1 | 165 |

| Current | 10 | rs9322120 | G/A | 6 | 148047385 | 0.132 | 4.96 | −9.1 | 5.54E-06 | 1.87E-07 | 2.71E-07 | SASH1 | 165 |

| Current | 10 | rs1973858 | T/C | 6 | 148049408 | 0.132 | 4.95 | −9.08 | 5.63E-06 | 2.03E-07 | 2.88E-07 | SASH1 | 163 |

| Current | 10 | rs7746768 | C/G | 6 | 148056613 | 0.132 | −4.95 | 9.06 | 5.71E-06 | 2.23E-07 | 3.09E-07 | SASH1 | 156 |

| Current | 10 | rs351326 | A/C | 6 | 93402467 | 0.0806 | −4.31 | 12.8 | 5.95E-03 | 9.16E-07 | 6.78E-06 | EPHA7 | intron |

| Current | 15 | rs6454802 | T/C | 6 | 90104480 | 0.392 | 1.83 | −7.71 | 9.57E-02 | 5.58E-07 | 1.25E-07 | BACH2 | intron |

| Current | 15 | rs12202119 | T/A | 6 | 90105471 | 0.392 | 1.82 | −7.68 | 9.65E-02 | 5.64E-07 | 1.25E-07 | BACH2 | intron |

| Current | 15 | rs11753332 | A/G | 6 | 90109434 | 0.392 | −1.8 | 7.64 | 9.81E-02 | 5.71E-07 | 1.25E-07 | BACH2 | intron |

| Current | 15 | rs12194007 | T/G | 6 | 90113440 | 0.392 | 1.79 | −7.6 | 9.93E-02 | 5.79E-07 | 1.26E-07 | BACH2 | intron |

| Current | 15 | rs12196749 | A/G | 6 | 90110096 | 0.442 | −1.64 | 7.32 | 1.35E-01 | 2.10E-06 | 5.25E-07 | BACH2 | intron |

| Current | 20 | rs9471517 | C/T | 6 | 12341521 | 0.163 | 3.62 | −13.3 | 2.33E-04 | 1.04E-06 | 8.32E-07 | ARG1/MED23 | 12342 |

| Current | 20 | rs9493000 | C/T | 6 | 131487451 | 0.0603 | −0.115 | −13.5 | 9.40E-01 | 3.83E-06 | 3.45E-07 | ARG1/MED23 | 131487 |

| Current | 20 | rs7740929 | G/A | 6 | 131487482 | 0.0514 | 0.524 | 11.4 | 7.40E-01 | 3.01E-05 | 6.69E-07 | ARG1/MED23 | 131487 |

| Current | 20 | rs9492992 | T/G | 6 | 131481287 | 0.0514 | 0.543 | 11.4 | 7.30E-01 | 3.22E-05 | 7.34E-07 | ARG1/MED23 | 131481 |

| Current | 20 | rs12481734 | C/G | 21 | 23699432 | 0.0967 | 1.48 | −20.4 | 5.39E-01 | 2.02E-06 | 7.11E-07 | D21S2088E | 23699 |

| Current | 20 | rs17154431 | A/G | 5 | 126342485 | 0.0668 | 4.83 | −15.9 | 9.17E-03 | 7.05E-07 | 4.78E-06 | GRAMD3 | 126342 |

| Current | 20 | rs901508 | T/C | 5 | 2006893 | 0.0943 | −3.64 | 16.1 | 2.95E-02 | 7.84E-08 | 3.84E-07 | IRX4 | 2007 |

| Current | 20 | rs4594252 | C/A | 16 | 55286934 | 0.102 | −1.11 | 15 | 3.02E-01 | 1.66E-07 | 7.71E-07 | IRX6 | 55287 |

| Current | 20 | rs7973791 | C/A | 12 | 91050948 | 0.0568 | −5.53 | 17.3 | 2.84E-03 | 3.64E-07 | 2.56E-06 | KERA | 3′ UTR |

| Current | 20 | rs7959834 | C/T | 12 | 91050279 | 0.0568 | 5.53 | −17.3 | 2.84E-03 | 3.71E-07 | 2.61E-06 | KERA | 91050 |

| Current | 20 | rs12228056 | T/C | 12 | 91036196 | 0.0568 | −5.53 | 17.2 | 2.85E-03 | 4.42E-07 | 3.07E-06 | KERA | 91036 |

| Current | 20 | rs3798221 | T/G | 6 | 160577116 | 0.188 | −2.32 | 11.5 | 2.37E-02 | 6.92E-07 | 4.93E-06 | LPA | intron |

| Current | 20 | rs12033204 | A/C | 1 | 212274784 | 0.0555 | −2.06 | 19.1 | 3.35E-01 | 1.01E-06 | 8.87E-07 | PPP2R5A | 212275 |

| Current | 20 | rs16991403 | T/C | 20 | 1092170 | 0.0596 | 1.67 | 14.6 | 3.74E-01 | 6.47E-05 | 1.00E-06 | PSMF1 | 1092 |

| Current | 20 | rs9899604 | C/T | 17 | 71414692 | 0.0549 | 4.45 | −17.3 | 7.31E-03 | 2.71E-07 | 2.00E-06 | SOX9 | 71415 |

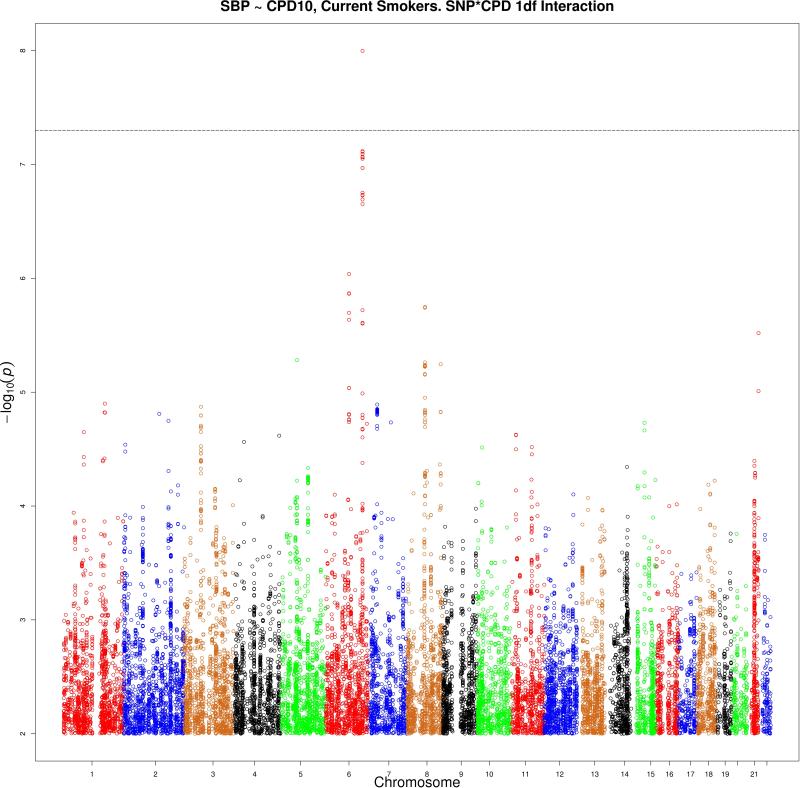

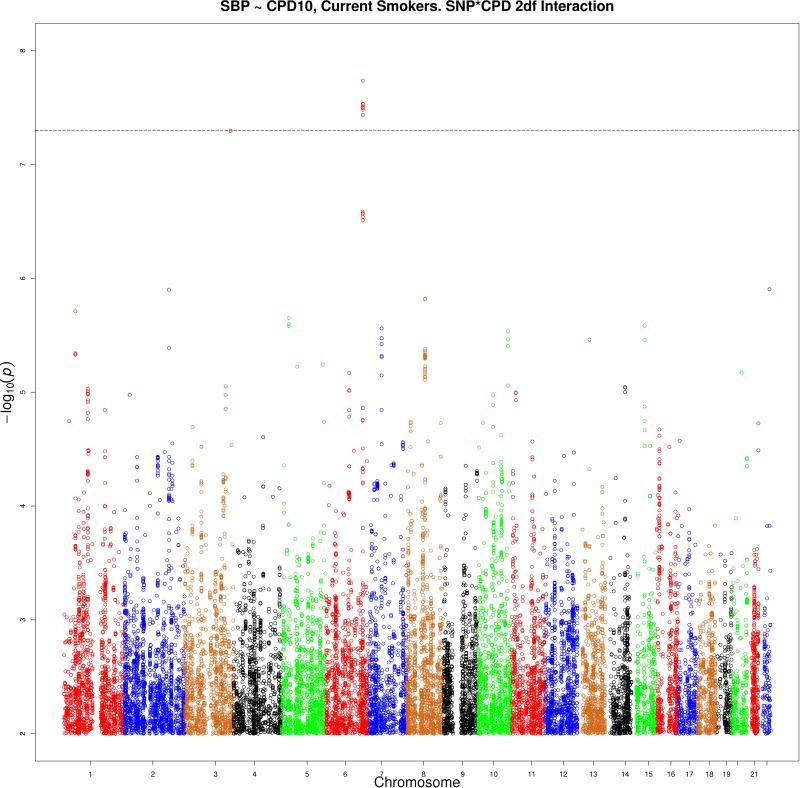

Manhattan plots (using inflation-adjusted p-values) for the analysis of the Current Smokers sample with CPD10 are shown in Figure 4 (1df test) and Figure 5 (2df test). Manhattan plots for the remaining eight analyses are in the supplementary materials.

Figure 4. Manhattan plot for Current Smokers sample, CPD10, 1df test.

Figure 4 shows the manhattan plot for the analysis of the Current Smokers sample using the CPD10 interacting covariate. The –log(P) value adjusted for genomic inflation for the 1df test is shown. A significant locus is located on chromosome 6 (−log(P) = 8.0) 149 kb from SASH1. A suggestively associated locus is also located on chromosome 6 (−log(P) = 6.0) in an intron of EPHA7.

Figure 5. Manhattan plot for Current Smokers sample, CPD10, 2df test.

Figure 4 shows the manhattan plot for the analysis of the Current Smokers sample using the CPD10 interacting covariate. The –log(P) value adjusted for genomic inflation for the 2df test is shown. A significantly associated locus is located on chromosome 6 (−log(P) = 7.7) 149 kb from SASH1. A second significantly associated locus is located on chromosome 7 (−log(P) = 7.3) about 36 kb from the genes KLHL6 and KLHL24.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed the interaction effects of smoking intensity (i.e, cigarettes per day [CPD]) and genetic variants on SBP in three different smoking exposure cohorts (current smokers; current and former smokers; and current, former, and never smokers) using three different CPD interacting covariates (defined at CPD cutoffs of 10, 15, and 20). These nine analyses yielded two loci with genome-wide significance and 19 suggestive (inflation-adjusted p < 10−6) associations. Both of the significant loci were based on the analysis of the Current Smokers sample and a CPD cutoff of 10. This finding has important implications for the design of future studies analyzing the effects of smoking-SNP interactions on blood pressure. The other two samples, All Subjects and Ever Smokers, are approximately 6.3 and 3.2 times larger than the Current Smokers sample, respectively (Table I). The observation that they produced no genome-wide significant findings compared to the two significant findings from the Current Smokers sample (as well as far fewer suggestive associations) in spite of these much larger sample sizes suggests that the genetic modulation of smoking effects on blood pressure diminishes after a subject stops smoking. As a consequence, analyses of current smokers may be prioritized for discovery of gene-smoking interactions on BP, even if that means a substantial reduction in sample size relative to a sample containing subjects who have never smoked or who have quit smoking.

These data are less conclusive with respect to the CPD cutoff that optimizes gene discovery. While the most significant results were obtained using a cutoff of 10 cigarettes per day, the majority of the results with genomic-controlled p < 10−6 were obtained using a cutoff of 20. The majority of these suggestive associations were detected in the Current Smokers sample, however, which contained only 165 subjects who smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day. Although the minor allele frequency cutoff of 5% helped ensure that at least 16 copies of the minor allele were present in the heavier smoking group, this value still allows for substantial instability in the regression estimates. As the majority of these suggestive associations were found for SNPs having MAF between 5% and 10%, these results should be treated with caution.

Based on these data, we conclude that current smokers revealed the strongest signals for gene-smoking interaction on BP, including two genome-wide significant associations. The strongest result was for rs9399633 (inflation-adjusted 1df p = 1.00 × 10−8, 2df p = 1.83 × 10−8, Table III), located about 150 kb upstream of SASH1 (SAM and SH3 domain containing 1). SASH1 is best known as a tumor suppressor gene for several types of cancer including colon (Nitsche, U et al. 2012), breast (Zeller, C et al. 2003), and melanoma (Lin, S et al. 2012). It is also located in a susceptibility locus for lung cancer (Bailey-Wilson, JE et al. 2004), and SASH1 over-expression reduces the viability, proliferation, and migration of lung cancer cells whereas targeted silencing of SASH1 by RNA interference has opposing effects (Chen, EG et al. 2012). At least three studies investigated the influence of tobacco exposure on gene expression in circulating blood cells found that SASH1 expression was significantly correlated with tobacco exposure (although the direction of the change varied across studies) (Beineke, P et al. 2012; Charles, PC et al. 2008; Verdugo, RA et al. 2013). This smoking-induced change in expression suggests a possible mechanism explaining the interaction between smoking and rs9399633. The effect of SASH1 on blood pressure may be mediated through its expression in endothelial cells of microvascular beds, where it contributes to activation of the NF-κB complex and proinflammatory cytokines (Dauphinee, SM et al. 2013). Motivated by the co-morbidity of inflammatory processes and hypertension in metabolic syndrome, a recent analysis of SNP-SNP interactions among inflammation genes for association with BP suggested a BP-regulatory role for interactions among members and regulators of the NF-κB complex (Basson, JJ et al. 2014). Furthermore, a suggestive association between SASH1 and diabetic nephropathy, a risk factor for hypertension, has been identified in a genome-wide association study of African Americans (Mcdonough, CW et al. 2011). Thus, several lines of evidence support the biologic plausibility that SASH1 plays a role in the modulating effect of tobacco on blood pressure.

The other genome-wide significant association with SBP was located on chromosome 3, with the strongest result (rs11717948, inflation-adjusted 2df p = 5.03 × 10−8, Table III) located approximately 36 kb downstream of KLHL6 and 44 kb upstream of KLHL24. Although relatively little is known about these genes, they belong to the Kelch-like gene family which contains several evolutionarily conserved domains and several of whose members are associated with Mendelian diseases (Dhanoa, BS et al. 2013); notably, rare mutations in KLHL3 alter renal ion transport and cause familial hyperkalemic hypertension (Louis-Dit-Picard, H et al. 2012). Expression of KLHL6 in CD133(+) cells has also been associated with coronary artery disease (Liu, Det al. 2011), and KLHL24 has been shown to regulate kainite receptors (Laezza, F et al. 2007), which are known to play a role in nicotine dependence (Kenny, PJ et al. 2003; Ma, JZ et al. 2010; Vink, JM et al. 2009). The 2df result at this locus is driven by the SNP main effect (inflation-adjusted main effect p = 1.47 × 10−8, 1df p = 8.34 × 10−3, Table III).

These results indicate that gene-smoking interactions can reveal novel BP loci and that a sample consisting exclusively of current smokers likely provides the greatest power to detect such interactions even when the sample size is considerably smaller than an alternative sample containing former smokers and those who have never smoked. In addition, these analyses implicate SASH1 as modulating the effect of smoking on BP.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It only analyzed data from one ethnic group, Caucasians, thus limiting generalizability to other racial and ethnic groups. Smoking status and CPD were determined at the time of the visit without reference to the duration of smoking or smoking abstinence; therefore, subjects who recently quit were considered equal to non-smokers and new smokers were considered equal to life-long smokers. The CPD values analyzed were based on self-reports that averaged changing CPD values over time and may not be precise. Finally, although these hypotheses will be investigated in a large CHARGE Consortium (devoted to gene-lifestyle interactions in cardiovascular traits), our findings have not been replicated in external samples.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate very helpful comments from Laura Beirut, M.D., both during the design of this investigation as well as on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We thank all participants of the Framingham Heart Study for their dedication to cardiovascular health research. Our investigation was supported partly by grants R01 HL107552, R01 HL118305, and K25HL121091 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The Framingham Heart Study is conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with Boston University (Contract No. N01-HC-25195). Funding for SHARe Affymetrix genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-64278. This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with investigators of the Framingham Heart Study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Framingham Heart Study, Boston University, or the NHLBI.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any financial or commercial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Bailey-Wilson JE, Amos CI, Pinney SM, Petersen GM, De Andrade M, et al. A major lung cancer susceptibility locus maps to chromosome 6q23-25. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:460–474. doi: 10.1086/423857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson JJ, De Las Fuentes L, Rao DC. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism-Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Interactions Among Inflammation Genes in the Genetic Architecture of Blood Pressure in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Hypertens. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beineke P, Fitch K, Tao H, Elashoff MR, Rosenberg S, et al. A whole blood gene expression-based signature for smoking status. BMC Med Genomics. 2012;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Kuyt F, Jacob P,, 3rd Influence of nicotine on cardiovascular and hormonal effects of cigarette smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36:74–81. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles PC, Alder BD, Hilliard EG, Schisler JC, Lineberger RE, et al. Tobacco use induces anti-apoptotic, proliferative patterns of gene expression in circulating leukocytes of Caucasian males. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:38. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EG, Chen Y, Dong LL, Zhang JS. Effects of SASH1 on lung cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion in vitro. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:1393–1401. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauphinee SM, Clayton A, Hussainkhel A, Yang C, Park YJ, et al. SASH1 is a scaffold molecule in endothelial TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2013;191:892–901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanoa BS, Cogliati T, Satish AG, Bruford EA, Friedman JS. Update on the Kelch- like (KLHL) gene family. Hum Genomics. 2013;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret GB. Genome-wide association studies: contribution of genomics to understanding blood pressure and essential hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MS, Jucha E, Luz Y. Blood pressure in smokers and nonsmokers: epidemiologic findings. Am Heart J. 1986;111:932–940. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ, Gasparini F, Markou A. Group II metabotropic and alpha-amino-3- hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA)/kainate glutamate receptors regulate the deficit in brain reward function associated with nicotine withdrawal in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:1068–1076. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laezza F, Wilding TJ, Sequeira S, Coussen F, Zhang XZ, et al. KRIP6: a novel BTB/kelch protein regulating function of kainate receptors. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, et al. 2012 A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Zhang J, Xu J, Wang H, Sang Q, et al. Effects of SASH1 on melanoma cell proliferation and apoptosis in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:1243–1248. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Glaser AP, Patibandla S, Blum A, Munson PJ, et al. Transcriptional profiling of CD133(+) cells in coronary artery disease and effects of exercise on gene expression. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:227–236. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.491611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis-Dit-Picard H, Barc J, Trujillano D, Miserey-Lenkei S, Bouatia-Naji N, et al. KLHL3 mutations cause familial hyperkalemic hypertension by impairing ion transport in the distal nephron. Nat Genet. 2012;44:456–460. S451–453. doi: 10.1038/ng.2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Nussbaum J, Li MD. Significant association of glutamate receptor, ionotropic N-methyl-D-aspartate 3A (GRIN3A), with nicotine dependence in European- and African-American smokers. Hum Genet. 2010;127:503–512. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0787-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonough CW, Palmer ND, Hicks PJ, Roh BH, An SS, et al. A genome-wide association study for diabetic nephropathy genes in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2011;79:563–572. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche U, Rosenberg R, Balmert A, Schuster T, Slotta-Huspenina J, et al. Integrative marker analysis allows risk assessment for metastasis in stage II colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;256:763–771. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318272de87. discussion 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Lorca R, Grilo A, Martinez-Larrad MT, Manzano L, Serrano-Hernando FJ, et al. Sex and body mass index specific regulation of blood pressure by CYP19A1 gene variants. Hypertension. 2007;50:884–890. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G, Gu CC, Kraja AT, Arnett DK, Myers RH, et al. Genetic effect on blood pressure is modulated by age: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network Study. Hypertension. 2009;53:35–41. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simino J, Sung YJ, Kume R, Schwander K, Rao DC. Gene-alcohol interactions identify several novel blood pressure loci including a promising locus near SLC16A9. Front Genet. 2013;4:277. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung YJ, De Las Fuentes L, Schwander KL, Simino J, Rao DC. Gene-Smoking Interactions Identify Several Novel Blood Pressure Loci in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Hypertens. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo RA, Zeller T, Rotival M, Wild PS, Munzel T, et al. Graphical modeling of gene expression in monocytes suggests molecular mechanisms explaining increased atherosclerosis in smokers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e50888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Smit AB, De Geus EJ, Sullivan P, Willemsen G, et al. Genome-wide association study of smoking initiation and current smoking. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorman A, Lumley T, Mcknight B, Rice K. Behavior of QQ-plots and genomic control in studies of gene-environment interaction. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Weedon MN, Purcell S, Lettre G, Estrada K, et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:807–812. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller C, Hinzmann B, Seitz S, Prokoph H, Burkhard-Goettges E, et al. SASH1: a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 6q24.3 is downregulated in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:2972–2983. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RR, Song YY, Fan M, Li YH, Jiang Z, et al. [Effects of an insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin converting enzyme gene on the changes of serum lipid ratios and blood pressure induced by a high-carbohydrate and low-fat diet]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2013;44:731–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.