Abstract

Background and Purpose

T16Ainh-A01, CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA are identified as selective inhibitors of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel (CaCC). The aim of this study was to examine the chloride-specificity of these compounds on isolated resistance arteries in the presence and absence (±) of extracellular chloride.

Experimental Approach

Isolated resistance arteries were maintained in a myograph and tension recorded, in some instances combined with microelectrode impalement for membrane potential measurements or intracellular calcium monitoring using fura-2. Voltage-dependent calcium currents (VDCC) were measured in A7r5 cells with voltage-clamp electrophysiology using barium as a charge carrier.

Key Results

Rodent arteries preconstricted with noradrenaline or U46619 were concentration-dependently relaxed by T16Ainh-A01 (0.1–10 μM): IC50 and maximum relaxation were equivalent in ±chloride (30 min aspartate substitution) and the T16Ainh-A01-induced vasorelaxation ±chloride were accompanied by membrane hyperpolarization and lowering of intracellular calcium. However, agonist concentration–response curves ±chloride, with 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 present, achieved similar maximum constrictions although agonist-sensitivity decreased. Contractions induced by elevated extracellular potassium were concentration-dependently relaxed by T16Ainh-A01 ±chloride. Moreover, T16Ainh-A01 inhibited VDCCs in A7r5 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA (0.1–10 μM) induced vasorelaxation ±chloride and both compounds lowered maximum contractility. MONNA, 10 μM, induced substantial membrane hyperpolarization under resting conditions.

Conclusions and Implications

T16Ainh-A01, CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA concentration-dependently relax rodent resistance arteries, but an equivalent vasorelaxation occurs when the transmembrane chloride gradient is abolished with an impermeant anion. These compounds therefore display poor selectivity for TMEM16A and inhibition of CaCC in vascular tissue in the concentration range that inhibits the isolated conductance.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| BKCa (KCa1.1) |

| TMEM16A (CaCC) |

| VDCCs |

| LIGANDS | ||

|---|---|---|

| ACh | Indomethacin | Noradrenaline |

| Apamin | L-NAME | Phentolamine |

| Aspartate | Nifedipine | TRAM-34 |

| Atropine | Nitric oxide (NO) | U46619 |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

The TMEM16A protein (anoctamin-1) has been established as a calcium-activated chloride channel (CaCC) by heterologous expression (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008) and in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) as the native CaCC (Manoury et al., 2010; Thomas-Gatewood et al., 2011; Dam et al., 2014). Small molecules that inhibit the Ca2+-activated chloride current (ICl(Ca)) attributed to TMEM16A have been identified (De La Fuente et al., 2008; Namkung et al., 2011). In the relatively few years since their development and availability, these inhibitors – T16Ainh-A01 and CaCCinh-A01 – have been used as specific pharmacological tools to investigate the role of TMEM16A in ICl(Ca) and the cellular signalling processes attributed to this current. In particular, studies of TMEM16A/CaCC in epithelial physiology and pathophysiology have extensively utilized both T16Ainh-A01 (Namkung et al., 2011; Mazzone et al., 2012; Sauter et al., 2015) and CaCCinh-A01 (De La Fuente et al., 2008; Bill et al., 2014; Buchholz et al., 2014; Sauter et al., 2015). The newest compound, MONNA, has thus far been demonstrated to inhibit the endogenous ICl(Ca) of Xenopus laevis oocytes (Oh et al., 2013) known to be carried by xANO1 (Schroeder et al., 2008), as well as heterologously expressed human ANO1 (Oh et al., 2013). In terms of vascular actions, the effects of CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA on vascular preparations have not been examined but T16Ainh-A01 is reported to relax agonist-contracted isolated resistance arteries (Forrest et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2013), pulmonary arteries (Sun et al., 2012) and abolish methoxamine-stimulated contractility of murine thoracic aorta (Davis et al., 2013).

Polyatomic anions such as propionate, aspartate and gluconate have relatively large atomic radii that physically restrict their permeability and conductance through anion channels. A selectivity sequence generated for ICl(Ca) in acinar cells from rat parotid gland has shown that aspartate has a low permeability relative to Cl−, with Pasp/PCl of 0.1 (Perez-Cornejo et al., 2004). The ICl(Ca) in acinar cells has been convincingly demonstrated to be TMEM16A-dependent (Yang et al., 2008; Romanenko et al., 2010) as has the ICl(Ca) of rodent resistance arteries (Thomas-Gatewood et al., 2011; Dam et al., 2014). The accumulation of intracellular Cl− in smooth muscle cells occurs primarily via Na+, K+, Cl− (NKCC) co-transport (Chipperfield and Harper, 2000). Replacement of all extracellular Cl− with large anions such as gluconate does not support the transport function of NKCC (Russell, 2000). This has been substantiated in rat femoral arteries via double-barrelled Cl−-sensitive microelectrode impalements: gluconate substitution for Cl− results in a lowering of intracellular Cl− to negligible levels within 10 min (Davis et al., 1997). Thus impermeable anions can substituted for chloride to abolish intracellular chloride accumulation and probe the contribution of anion channels such as ICl(Ca)/TMEM16A in smooth muscle preparations.

Noradrenaline (NA) is an effective vasoconstrictor of rat mesenteric resistance arteries irrespective of the presence of extracellular chloride: replacement of chloride with aspartate has been reported to have nominal effects upon maximal NA-induced contraction and sensitivity (EC50) (Boedtkjer et al., 2008); gluconate replacement resulted in a resting membrane potential (Vm) and depolarization with NA that was comparable to those with chloride present (Nilsson et al., 1998), while propionate substitution lowered but did not prevent α-adrenoceptor mediated constriction (Parai and Tabrizchi, 2005). Thus, agonist-induced vascular contractility in rodent resistance arteries can occur independently of chloride and CaCCs. This implies that blood vessels unable to maintain and exploit an active transmembrane chloride gradient could be used to determine whether chloride channel inhibitors exert vasoactive effects other than the closure of a chloride channel. We hypothesized that in the absence of an effective transmembrane chloride gradient – a condition where depolarization via ICl(Ca) is not possible – a specific CaCC inhibitor would be ineffective against agonist-induced vascular tone. In the current study, we address this hypothesis with the following questions: What effects do T16Ainh-A01, CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA exert upon agonist-induced responses in rodent small resistance arteries? Are these compounds effective in chloride-substitution experiments? Finally, how do their vasoactive effects relate to Vm and calcium handling?

Methods

Animals

Adult Wistar rats (male, ∼ 300–400g) and C57BL/6 mice (male and female, ≥ 8 weeks) were housed at the animal facility at the Department of Biomedicine according to the Institute's guidelines and in accordance with the Danish legislation for animal research and EU standards (Directive 2010/63/EU). A total of 84 rats and 37 mice were used in the experiments described here and in the supporting information. Animals were killed by CO2 inhalation, which was performed by qualified personnel. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Isometric force measurement from isolated small arteries

Tissues of interest were rapidly dissected free and transferred to ice-cold physiological saline solution (PSS). Third-order branches (≤2 mm in length) of mesenteric arteries (MSA) from rat (

internal diameter 346 ± 17 μm, 253 vessels) or mouse (244 ± 8 μm, 52 vessels) or mouse middle cerebral arteries (MCA, 154 ± 3 μm, 19 vessels) were isolated and mounted in a wire myograph (Danish Myo Technology, Skejby, Denmark) for recording of isometric force. In some experiments, the endothelium was removed by subjecting mounted vessels to a flow of air through the lumen (≈5 mL 2×) before normalization. All vessels were maintained at 37°C in a PSS gassed with 5% CO2 in air (21% O2) to give a pH of 7.4. Vessels were normalized by a passive stretch–tension protocol to permit optimal tension development (Mulvany and Halpern, 1977). After equilibration, vessel viability was determined for MSAs by repeated exposures to 10 μM NA. In murine MCAs, vessel viability was determined by addition of 1 μM U46619 (a stable thromboxane A2 analogue) and a subsequent challenge with high-potassium PSS (K-PSS). Endothelial integrity was determined by 3 μM NA followed by subsequent administration of 5 μM ACh (average relaxation 75%). In vessels with the endothelium removed, this was confirmed by failure to relax to ACh (≤10%).

In all instances of chloride-free conditions, the vessels were incubated in the chloride-free PSS (for composition see succeeding text) for a minimum of 30 min to permit dissipation of the transmembrane chloride gradient. Furthermore, vessels were stimulated with 10 μM NA midway through the initial chloride-free period to encourage exit of residual intracellular chloride. In the K-PSS experiments, the vessels were in chloride-free solutions for an average of 60 min before the start of the protocol.

The experimental protocols for myography included (i) vasorelaxation to inhibitors and determination of IC50: arteries were incubated in either chloride-containing solutions (PSS) or chloride-free PSS then constricted with NA or U46619. A discrete concentration or cumulative concentrations (0.1–10 μM) of the inhibitor was applied to the constricted vessels. Paired DMSO (vehicle) experiments were performed. The maximal [DMSO] reached 0.1% (v/v) for an individual application and in IC50 experiments 0.19% (v/v). Vasorelaxation was also assessed in vessels denuded of endothelium or in the presence of 100 μM L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (30 min pre-incubation). (ii) Cumulative concentration–response curves (CCRC) to agonists: control CCRC to NA or U46619 were constructed, then the samples were incubated with the inhibitor [or DMSO; up to 0.1% (v/v)] for 15 min before repeating the CCRC. Unless specifically stated otherwise, comparisons were made pairwise with up to four vessels from the same animal mounted. (iii) Elevated extracellular potassium: the arteries were incubated in PSS with and without chloride and challenged with a chloride-containing or chloride-free 60 mM K+ solution and T16Ainh-A01 or an equivalent volume of DMSO was added after a stable plateau was attained (at 5 min post-peak). Phentolamine (1 μM) was present in all solutions in these experiments to prevent the effects of neurotransmitter release from nerve terminals.

For myograph experiments, the PSS containing chloride had the following composition (in mM): NaCl, 115.88; KCl, 2.82; NaHCO3, 25; CaCl2, 1.6; KH2PO4, 1.18; MgSO4, 1.20, glucose, 5.5; EDTA, 0.03; HEPES, 10. In chloride-free PSS, NaCl and KCl were replaced with aspartate salts and CaCl2 with CaSO4. K-PSS was made by replacing all NaCl with KCl or K-aspartate ([K+] 119.88 mM). The 60 mM K-PSS solutions were made by mixing appropriate volumes of PSS and K-PSS.

Simultaneous measurement of isometric force and Vm

Vessel segments (2 mm) were mounted in a single chamber wire myograph and normalized as described earlier. The Vm values for VSMCs were measured using sharp glass microelectrodes (AF100-64-10, World Precision Instruments Ltd, Hitchin, UK) pulled on a horizontal puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA). Voltage was recorded at 1 kHz via an amplifier (Intra 767, World Precision Instruments Ltd) and A-D convertor (PowerLab 4SP, ADInstruments, Dunedin, New Zealand). Microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl [average electrode resistance 96 MΩ (range 55–130 MΩ)] were used for recording. The reference electrode (flat-tip Ag/AgCl probe; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) was immersed in the bath solution and before the cell was impaled, the amplifier was zeroed with the recording electrode in the bath solution to balance any offset. The inclusion criteria for a successful impalement and analysis were: (i) an abrupt, negative deflection in potential upon penetration; (ii) a rapid return to the pre-impalement potential level upon withdrawing the electrode to the bath solution; and (iii) a stable electrode resistance throughout the recording. The liquid junction potential estimated for the aspartate solution (chloride-free) was minor (−1.3mV; Junction Potential Calculator, Clampex10, Molecular Devices Ltd, Wokingham, UK) and therefore data were not corrected for this.

Simultaneous measurement of isometric force and [Ca2+]i

Vessel segments (2 mm) were mounted in a single chamber wire myograph. After normalization, background fluorescence was measured and the arteries were given the standard start protocol in PSS (as described earlier). Subsequently, the arteries were washed with chloride-free PSS containing 1 μM phentolamine (which was present throughout the remainder of the experiment) for loading at 37°C with 6 μM of the Ca2+-sensitive fluorophore fura-2-AM (Life Technologies Europe BV, Naerum, Denmark) dissolved in a load mix (composed of 0.04g Pluronic F-127 (Life Technologies Europe BV) and 200 μL Cremophor EL (Sigma-Aldrich, Brøndby, Denmark) in 1 mL DMSO) for two 30 min periods in chloride-free PSS. The [DMSO] in the chamber was 0.04% (v/v). After being loaded and washed, fura-2-loaded arteries were excited with alternating wavelengths (340 and 380 nm) and subsequent emission (>510 nm) was recorded using a Leica DM IRB inverted microscope (Ballerup, Denmark) with a × 20 objective (N.A. 0.5) connected to a Photon Technology International Deltascan system (Birmingham, NJ, USA). Arteries were then exposed to two chloride-free 60 mM K-PSS challenges: an initial K-PSS to assess contractility (stable 5 min plateau defined as 100%) and a subsequent K-PSS where at the 5 min plateau level 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 5 μM T16Ainh-A01 were added cumulatively to the bath. Background fluorescence measured prior to loading was subtracted from the measured emissions.

Cell culture

Rat embryonic thoracic aorta VSMCs (A7r5) were cultured in DMEM medium (In Vitro, Fredensborg, Denmark) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% L-glutamine and 0.1% KPS (kanamycin 2 g, penicillin 106 IU, streptomycin 1 g in 20 mL PBS) in an incubator maintained at 37°C with humidified 5% CO2.

Whole-cell patch clamp of A7r5 cells

Confluent cells were washed with 37°C PBS three times and incubated for 15 min with non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Dissociated cells were centrifuged at 3000× g and the pellet was suspended in PBS and transferred to tissue culture dishes (35 × 10 mm; Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Albertslund, Denmark) filled with PSS (composition as for myograph experiments). PBS composition was (in mM): NaCl, 138; KCl, 2.67; Na2HPO4, 8.1; KH2PO4, 1.47 at pH 7.4. After 20–30 min, A7r5 cells attached to the bottom of tissue culture dishes and were washed three times with bath solution. Cells were used for conventional voltage-clamp experiments within 2–3 h. All experiments were made at room temperature (22–24°C). Patch pipettes were prepared from borosilicate glass (PG15OT-7.5; Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, UK) pulled on a P-97 puller and fire-polished to achieve tip resistances in the range of 5–7 MΩ. Recordings were made with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices Ltd, Wokingham, UK) in whole-cell configuration. Data were sampled at 2 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Data acquisition and analysis were performed with Clampex 10.3 for Windows (Molecular Devices Ltd). Series resistance and capacitive current were routinely compensated. Ca2+ current was measured in accordance with a previously published protocol (Abd El-Rahman et al., 2013) using Ba2+ as the charge carrier. The pipette solution contained (in mM) CsCl, 135; Mg-ATP, 2.5; HEPES, 10; EGTA, 10; (pH 7.2). Bath solution contained (in mM) NaCl, 110; CsCl, 135; TEA-Cl, 4; MgCl2, 1.2; BaCl2, 10; HEPES, 10; glucose, 10 (pH 7.4). The whole-cell membrane current was recorded at a holding potential of −50mV and barium current (IBa) was generated by a voltage-step protocol from −80 to +50mV (200 ms duration, 10 mV increments). After the whole-cell I–V relationship had been established under these conditions, inhibitors were added to the bath solution and I–V curves were generated in the presence of the inhibitor. Current values were normalized to control peak current value (at +10mV).

Materials

The majority of chemicals and drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with the following exceptions: T16Ainh-A01 (2-[(5-ethyl-1,6-dihydro-4-methyl-6-oxo-2-pyrimidinyl)thio]-N-[4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-thiazolyl]acetamide) and CaCCinh-A01 (6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-2-[(2-furanyl-carbonyl)amino]-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[b]thiophene-3-carboxylic acid), which were purchased from Tocris (Abingdon, UK) and MONNA (N-((4-methoxy)-2-naphthyl)-5-nitroanthranilic acid), which was a gift from Professor C. Justin Lee (Korea Institute for Science and Technology, South Korea). Stock solutions were made by dissolving the compound in DMSO (T16Ainh-A01, CaCCinh-A01, MONNA and nifedipine), ethanol (U46619) or distilled water (phentolamine, NA, ACh and L-NAME) and were stored at −20°C until use. Further dilutions of NA and U46619 for concentration–response experiments were made in distilled water, while the CaCC inhibitors were diluted in DMSO. Drug and molecular target nomenclature conforms to the BJP Concise Guide to Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2013).

Statistical analysis

Force data (mN) were converted to tension (Nm−1) by dividing by twice the vessel segment length (mm) and the baseline tension values subtracted. Data are expressed as mean tension or mean percentage relaxation of agonist- or potassium-induced tone, with error bars representing SEM. While experiments were often performed in duplicate on arteries from a single animal, these were averaged thus the n value given always represents the number of animals used per group. Concentration–response curves were fitted to the CCRC data using four-parameter, non-linear regression curve fitting in Prism (v.5; GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA) with the following formula: Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/(1 + 10((LogEC50 − X) × Hill Slope)) where X is [agonist] (in log M), Y is the tension response, Top refers to Fmax (maximum tension), Bottom refers to Fmin (initial tension, constrained to 0 or 100) and the Hill Slope is variable. From these curves, logEC50 (the concentration required to constrict the vessel to half-maximal tone) or logIC50 (the concentration required to relax the vessel by 50%) and Fmax (maximal constriction or relaxation) were derived and compared using an extra sum-of-squares F test. Comparisons of ±Cl− were performed by Student's unpaired or paired two-tailed t-test, while comparisons of ±Cl− and ±drug were compared when possible by two-way anova followed by a post hoc test (Bonferonni) for multiple comparisons. In some instances, repeated-measures (RM) anova was used, as appropriate. Statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05 and nsd demotes not significantly different.

Results

T16Ainh-A01 relaxes preconstricted arteries

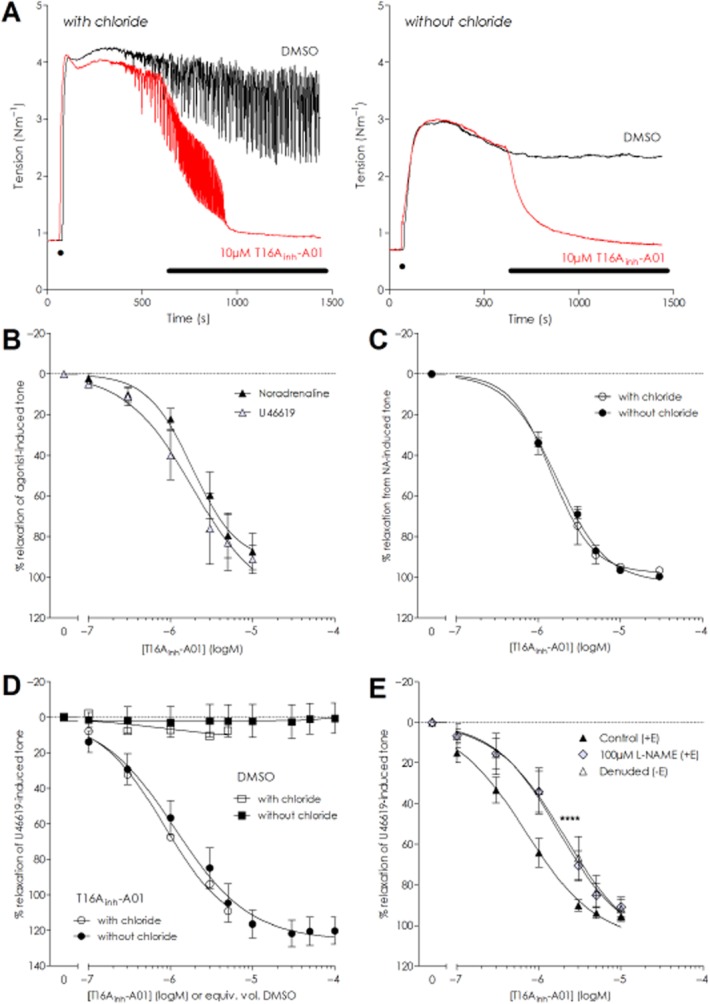

Rat MSAs maintained in normal or Cl−-free conditions were constricted with 10 μM NA, which elicited reproducible tension levels in the presence (2.62 ± 0.24 Nm−1, n = 11) and absence (1.79 ± 0.30 Nm−1, n = 12) of extracellular chloride, although the tension in chloride-free conditions was lower (P = 0.006). NA-stimulated vasomotion, observed as rhythmic oscillations in vascular tone, was present under normal conditions but absent in Cl−-free solution (Figure 1A) in agreement with our previous observation that vasomotion is a chloride-dependent phenomena (Boedtkjer et al., 2008). Application of 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 resulted in a near-complete relaxation of the arteries (Figure 1A and Supporting Information Fig. S1A and B) of comparable magnitude in the presence (94.2 ± 1.8%) and absence (91.2 ± 4.9%) of Cl− [n = 7; not significantly different (nsd) RM two-way anova]. At 100 μM, T16Ainh-A01 also relaxed arteries with (83.1 ± 11.5%, n = 4) and without Cl− (86.5 ± 8.3%, n = 5) but the vasorelaxation was not greater than that seen with 10 μM (Supporting Information Fig. S1C and D). Paired vehicle experiments (DMSO, 0.1% v/v) had negligible effect upon tone. Cumulative addition of T16Ainh-A01 upon 10 μM NA- or 100 nM U46619-stimulated rat MSA with chloride present caused comparative levels of relaxation (Figure 1B): logIC50 NA −5.66 ± 0.15 versus U46619 −5.91 ± 0.16 (P = 0.29; n = 4). The concentration-dependent relaxation of NA constrictions by T16Ainh-A01 was explored under normal and Cl−-free conditions (Figure 1C) and the T16Ainh-A01 logIC50 was not significantly different in the presence (−5.82 ± 0.04) or absence (−5.79 ± 0.01) of Cl− (P = 0.67; n = 5). Maximal reduction in NA-induced tone was attained with 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 in both conditions (98.0 ± 4.2% in control and 102.6 ± 1.7% in Cl−-free) while parallel vehicle control experiments lacked any significant effect upon tone or agonist sensitivity (data not shown). Murine MSA constricted with 100 nM U46619 (n = 8) were also readily relaxed by T16Ainh-A01 in normal PSS with a logIC50 of −6.15 ± 0.08 and maximal relaxation of 89% from initial tone at 5 μM T16Ainh-A01 (Supporting Information Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

T16Ainh-A01 effectively relaxes agonist-preconstricted resistance arteries maintained in the presence and absence of extracellular chloride. (A) Isometric tension recordings from paired experiments demonstrating the vasorelaxant effect of an acute application of 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 on 10 μM NA-preconstricted rat MSA with (left panel, red trace) and without extracellular chloride (right panel, red trace). The vehicle (DMSO, black traces) had no significant effect under either condition. Application of 10 μM NA is indicated by ‘●’ on the trace and bar indicates application of DMSO or T16Ainh-A01. (B) Cumulative application of T16Ainh-A01 on NA- or U46619-preconstricted rat arteries revealed that the inhibitor was equipotent in eliciting vasorelaxation (n = 4). (C) Cumulative application of T16Ainh-A01 relaxed NA-constricted rat MSAs equally well in the presence and absence of chloride (n = 5). (D) Mouse MCAs constricted with U46619 relaxed in response to T16Ainh-A01 in chloride (n = 6) and chloride-free (n = 5) conditions. (E) Removal of the endothelium or inhibition of NO production with 100 μM L-NAME in rat MSAs caused a rightward shift in the relaxation curves for T16Ainh-A01 but neither intervention prevented full relaxation (****P ≤ 0.0001 applicable to both curves vs. paired +E control, F-test).

Murine MCA constricted with 1 μM U46619 to 0.30 ± 0.05 Nm−1 with chloride present and 0.34 ± 0.03 Nm−1 without chloride (P = 0.51, unpaired t-test). The MCA relaxed equally well to T16Ainh-A01 irrespective of the presence or absence of chloride in the bath solution (Figure 1D): logIC50 −6.08 ± 0.32 in normal physiological solution (n = 6) versus −5.93 ± 0.11 in Cl−-free (P = 0.71; n = 5). In MCA, T16Ainh-A01 caused a complete vasorelaxation of the arteries tested; with vessels relaxing to 10–20% lower than the initial baseline level, implying that active tone developed by these arteries under isometric conditions was inhibited by T16Ainh-A01.

Whether the endothelium contributes to T16Ainh-A01-induced vasorelaxation was examined by pairwise comparison of rat MSA with the endothelium denuded (−E) or intact (+E) in chloride-containing solution. The +E and −E vessels were constricted with U46619 and cumulative administration of T16Ainh-A01 relaxed both vessel types (Figure 1E): while the vasorelaxation was more sensitive in the +E group (logIC50 +E −6.31 ± 0.07 vs. −E −5.91 ± 0.06; P = 0.0001, n = 6), both groups attained a maximal dilatation with 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (94.1 ± 5.7% in +E and 91.9 ± 4.8% in −E; P = 0.178). In +E vessels incubated with 100 μM L-NAME (Figure 1E), exposure to T16Ainh-A01 relaxed U46619-constricted vessels to the same extent as the paired control (control 95.7 ± 2.4% vs. L-NAME 90.9 ± 4.8%; P = 0.8395) but with a rightward shift in the concentration–response relationship (logIC50 −6.15 ± 0.12 in control vs. −5.78 ± 0.16 in L-NAME treated; P < 0.0001; n = 8). The similar response seen for −E and L-NAME-treated +E arteries indicates that a functional NO release from the endothelium enhances the sensitivity of the smooth muscle to T16Ainh-A01 but is not crucial for the vasorelaxant response per se. Experiments performed in the presence of atropine confirmed that T16Ainh-A01 was not causing vasorelaxation via muscarinic receptor stimulation (Supporting Information Fig. S4).

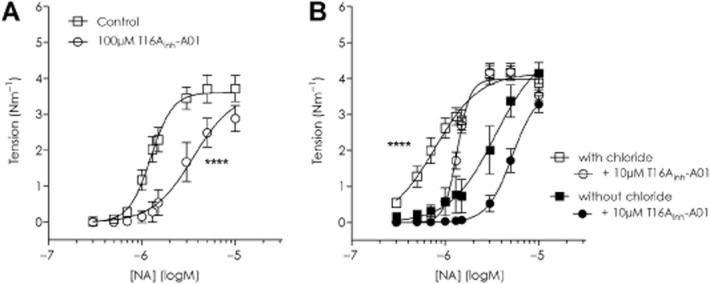

T16Ainh-A01 on agonist-stimulated contractility

When rat MSA were incubated with 100 μM T16Ainh-A01, the CCRC to NA was rightward shifted; logEC50 −5.90 ± 0.03 control versus −5.57 ± 0.07 with T16Ainh-A01 (P = 0.0001; n = 9, Figure 2A). The constriction level achieved with 10 μM NA was reduced from control levels of 3.72 ± 0.37 Nm−1 to 2.89 ± 0.36 Nm−1 with 100 μM T16Ainh-A01 (P = 0.06) while no significant changes occurred in the time or DMSO controls (Supporting Information Fig. S3A and B). The effect of 100 μM T16Ainh-A01 on the NA CCRC was considerably smaller than expected given that 100 μM T16Ainh-A01 almost fully relaxes NA-preconstricted rat MSA (Supporting Information Fig. S1C and D).

Figure 2.

In rodent arteries, in the presence of T16Ainh-A01, higher concentrations of NA are needed to initiate constriction but maximal tension at the highest NA concentration tested is not different from control. (A) Effect of 100 μM T16Ainh-A01 on rat MSAs and (B) 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 on mouse MSAs with chloride and without extracellular chloride. ****Denotes EC50 values for all graphs included were statistically significant from each other P ≤ 0.0001.

In murine MSA, the U46619 CCRC was shifted to the right in the presence of 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (logEC50 −7.80 ± 0.02 control vs. −7.59 ± 0.01 with T16Ainh-A01; n = 6, P < 0.0001) and maximal tension lowered by ∼10% (2.23 ± 0.03 Nm−1 in control vs. 2.08 ± 0.01 Nm−1 with T16Ainh-A01; P = 0.02, Supporting Information Fig. S2B). A similar shift in the NA CCRC for mouse MSA was observed (Figure 2B; control logEC50 −6.11 ± 0.04 vs. −5.87 ± 0.01 with 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 P < 0.0001; n = 6). Chloride-free conditions reduced NA-sensitivity in mouse MSA (logEC50 −5.47 ± 0.13) but a Cl−-independent inhibitory effect of T16Ainh-A01 was also observed as a further rightward shift of the CCRC (logEC50 −5.28 ± 0.04; n = 6, P < 0.0001). No significant differences were found between the four conditions with regard to the constriction achieved with 10 μM NA: 3.88 ± 0.27 Nm−1 with Cl−, 3.54 ± 0.16Nm−1 with Cl− and T16Ainh-A01, 4.15 ± 0.29 Nm−1 in Cl−-free and 3.29 ± 0.23 Nm−1 in Cl−-free with T16Ainh-A01 (P = 0.15 one-way anova).

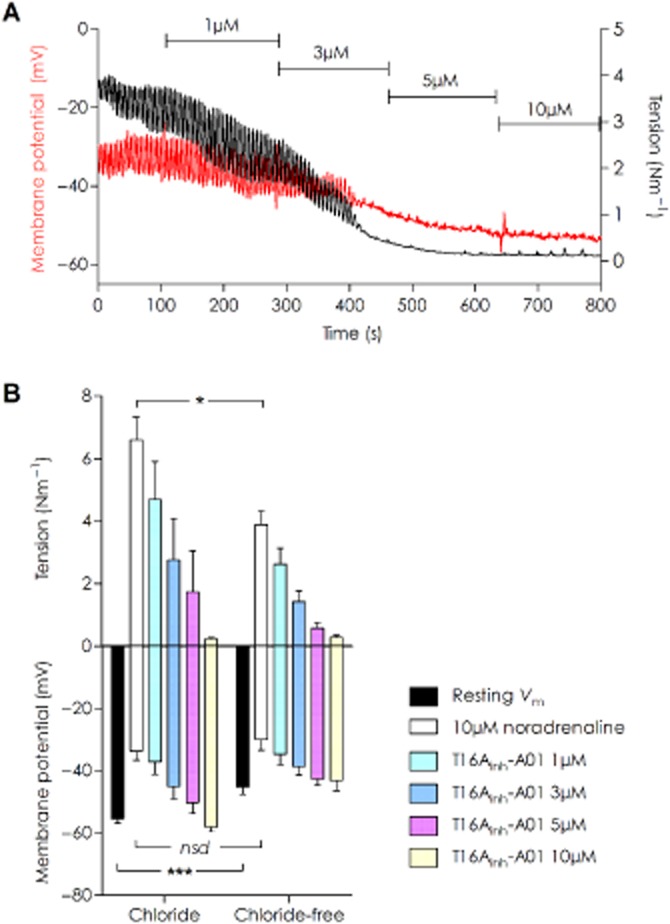

T16Ainh-A01 reverses membrane depolarization

In NA-stimulated arteries in the presence of extracellular Cl−, the vasomotion in the tension signal observed was preceded by an oscillation in the Vm (Figure 3A), while in Cl−-free conditions Vm and force oscillations were absent (not shown). Addition of T16Ainh-A01 to NA-stimulated rat MSA hyperpolarized the VSMCs and lowered the force whether chloride was present or not. While the resting Vm levels significantly differed according to condition (−55.5 ± 1.4 mV with Cl− and −45.3 ± 2.4 mV without; P < 0.001 unpaired t-test, n = 5), the addition of 10 μM NA depolarized the vessels to a similar level (−33.7 ± 3.0 mV with Cl− and −29.8 ± 3.5 mV in Cl−-free; P = 0.44 unpaired t-test, n = 5). Both voltage and tension were reversed to approximately baseline levels in the presence of 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (Figure 3B), Vm with Cl− in the presence of 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 −58.0 ± 1.6mV (P = 0.52 vs. chloride baseline, n = 4) and without Cl− −43.2 ± 3.2mV (P = 0.09 vs. Cl−-free baseline, n = 3). As the Vm returned to resting levels and did not hyperpolarize to a more negative potential irrespective of the Cl−-conditions, these data suggest closure of a Ca2+ conductance rather than opening of a K+ channel.

Figure 3.

Membrane hyperpolarization accompanies vasorelaxation induced by T16Ainh-A01 in rat MSAs under chloride and chloride-free conditions. (A) An original data trace of simultaneous tension and Vm recording in a 10 μM NA-stimulated vessel in normal chloride-containing solution. A concurrent lowering of Vm (red trace) and tension (black trace) was seen with increasing concentrations of T16Ainh-A01. (B) Summarized data for T16Ainh-A01 vasorelaxation and membrane hyperpolarization in chloride and chloride-free conditions [n = 5 for all data points except 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 in chloride (n = 4) and chloride-free (n = 3)]. Impalement Vm values were significantly different between the two conditions (***P = 0.0006). The depolarization induced by 10 μM NA was not different between with and without chloride; however, the corresponding force achieved was lowered in chloride-free (*P = 0.0125 by unpaired t-test).

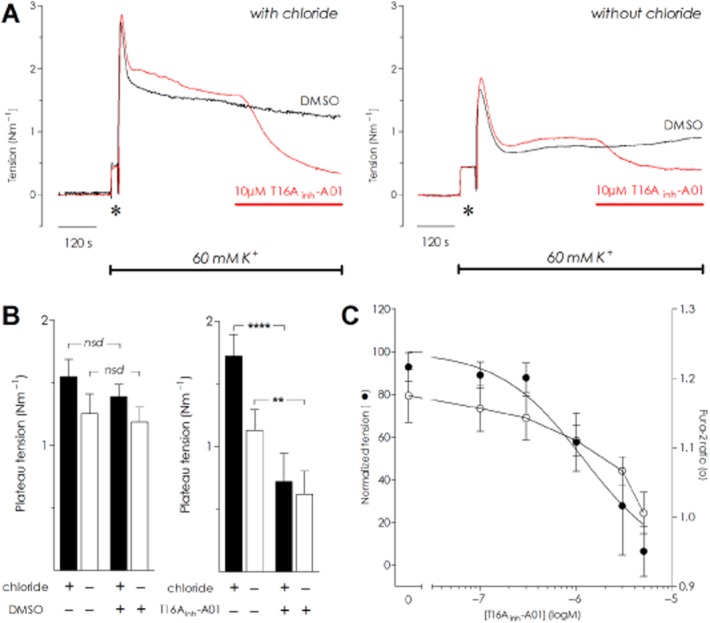

T16Ainh-A01 relaxes K+-induced contraction and lowers intracellular Ca2+

Assessment of voltage-dependent calcium channel (VDCC) activity and contraction due to Ca2+ influx in artery preparations can be investigated by elevating extracellular potassium to depolarize the smooth muscle cells directly. Rat MSA were maintained in normal Cl− or Cl−-free PSS before being constricted with 60 mM K+ solutions correspondingly with or without Cl−. The K+-evoked constriction had a significantly larger initial peak in Cl−-containing solution (2.62 ± 0.12 Nm−1, Figure 4A) than when Cl− was absent (1.76 ± 0.10 Nm−1; n = 5, P = 0.0004 paired t-test). After 5 min of exposure to high K+ solution, a stable plateau tension level was achieved and DMSO or 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 was applied (Figure 4A). After 5 min post-exposure to T16Ainh-A01, the K+-constriction was lowered to 41.9 ± 0.1% of the pre-drug plateau (P < 0.0001, two-way anova) with Cl− and 54.9 ± 0.2% of Cl−-free pre-drug plateau (P < 0.01, two-way anova) (Figure 4A and B; n = 5), while DMSO controls (0.1% v/v) were not significantly changed (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

T16Ainh-A01 relaxes constriction induced by elevated extracellular potassium in chloride and chloride-free conditions with a corresponding lowering of intracellular calcium. (A) Raw data traces depicting four mesenteric resistances from a single rat challenged by 60 mM potassium solution in chloride (left panel) or chloride-free conditions (right panel). The addition of 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (red bar) caused vasorelaxation that was not seen in corresponding vehicle (DMSO) controls. The * indicates wash-artefact. (B) Summarized data for the 60 mM potassium experiments on rat MSAs comparing the effect of DMSO (left panel) and 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (right panel) with and without chloride present (n = 5); nsd, not significantly different, **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001 by two-way anova. (C) In chloride-free conditions, cumulative addition of T16Ainh-A01 induced vasorelaxation of mouse MSAs stimulated with 60 mM K+ (n = 4). Intracellular calcium, measured by changes in the fura-2 ratio (depicted by open symbols) was lowered as tension was reduced (filled symbols).

In murine MSA, cumulative addition of lower concentrations of T16Ainh-A01 caused a concentration-dependent fall of 60 mM K+-stimulated tension (Cl−-free conditions; n = 4) that was accompanied by lowering of intracellular Ca2+ as detected by fura-2 fluorescence (Figure 4C). While tension was essentially abolished with 5 μM T16Ainh-A01, the fura-2 ratio remained elevated (1.01 ± 0.03) compared with the baseline ratio prior to elevating extracellular K+ (0.88 ± 0.04, P = 0.02). These data suggest that T16Ainh-A01 may affect VDCC.

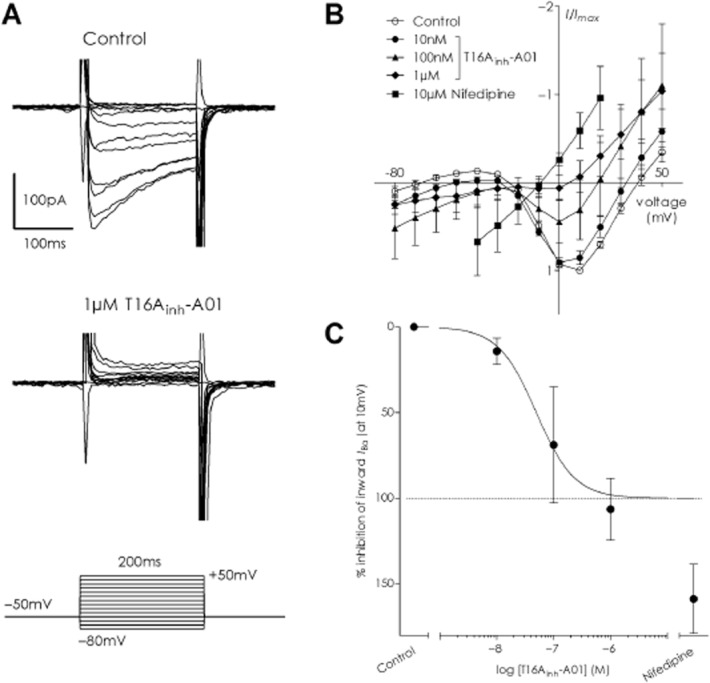

T16Ainh-A01 inhibits voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in A7r5 cells

To examine a suppressive effect of T16Ainh-A01 upon VDCC, we generated current–voltage (I–V) relationships using IBa in A7r5 cells (Figure 5A): IBa was activated at around −30mV and had peak current at +10mV, similar to previous reports (Tsubosaka et al., 2010; Martinsen et al., 2014). The I–V relationships generated by a voltage-step protocol before and after the addition of T16Ainh-A01 revealed that IBa was attenuated by the inhibitor: a concentration-dependent attenuation of the L-type Ca2+ current occurred (Figure 5B). Application of 10 μM nifedipine fully suppressed the I–V relationship (I/Imax values at +10mV in presence of nifedipine −0.59 ± 0.20: P = 0.0008 vs. control; paired t-test), confirming that the inward currents were L-type Ca2+ currents (n = 5 cells; Figure 5B). When peak inward current was normalized to control conditions at +10mV (I/Imax), a logIC50 of −7.30 ± 0.15 for inhibition of the nifedipine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ currents in A7r5 cells by T16Ainh-A01 was determined (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

T16Ainh-A01 inhibits voltage-dependent calcium conductance in A7r5 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. (A) Depicts a typical inward IBa trace obtained by applying depolarizing step pulses from the holding potential of −50 mV to test potentials between −80 and +50 mV (top trace) and how subsequent application of 1 μM T16Ainh-A01 to the same cell abolished all inward current (lower trace). (B) Average current-voltage relationship for normalized IBa in A7r5 cells (control) and the inhibitory effect of subsequent addition of T16Ainh-A01 (10 nM, 100 nM and 1 μM) or 10 μM nifedipine, a blocker of L-type calcium currents (nifedipine data from −40 to +20 mV only included). (C) The inhibitory profile of T16Ainh-A01 and nifedipine against the inward component of IBa calculated from the I/Imax values at +10 mV (calculated from data in panel B).

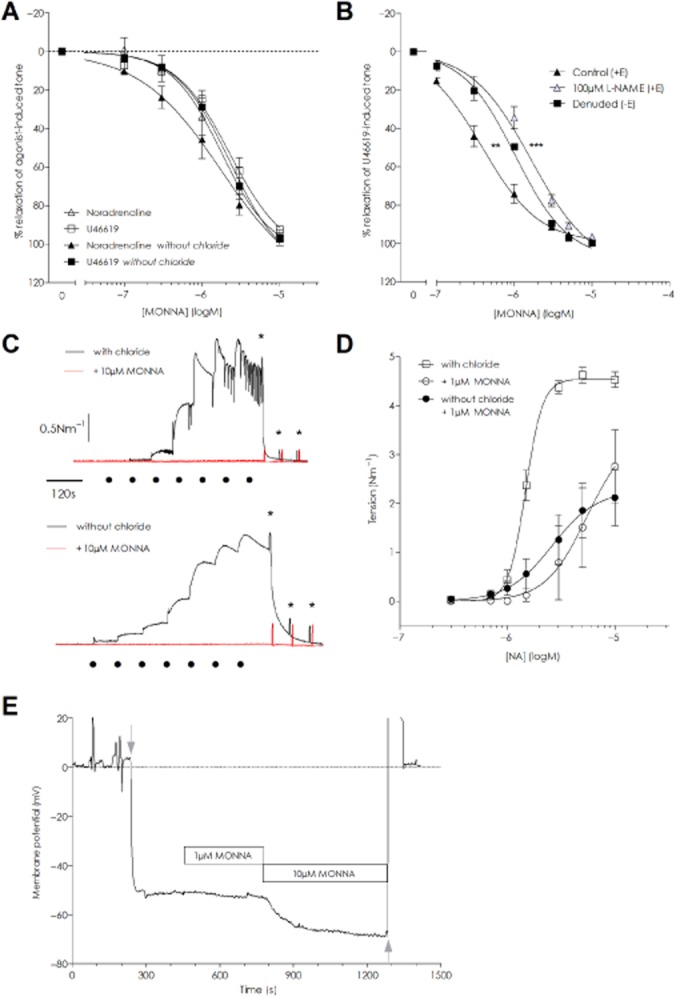

MONNA relaxes preconstricted arteries and inhibits vasoconstriction

Experiments on mouse MSA revealed MONNA to have equipotent vasorelaxant activity in the presence and absence of Cl−, irrespective of agonist (Figure 6A). Maximal vasorelaxation with 10 μM MONNA was 92.5 ± 1.3% for NA with Cl−, 97.1 ± 1.9% NA in Cl−-free, 96.8 ± 4.1% U46619 with Cl− and 96.9 ± 2.0% U46619 in Cl−-free (n = 5). The logIC50 values for MONNA on NA-evoked tension were similar in chloride and chloride-free solutions (−5.72 ± 0.14 and −5.87 ± 0.16, respectively) and for U46619 (−5.54 ± 0.15 and −5.70 ± 0.04 in chloride and chloride-free respectively). The endothelium also influenced MONNA-induced relaxation as experiments comparing arteries +E and −E and +E with 100 μM L-NAME revealed a rightward shift in the relaxation curve for MONNA when the endothelium was removed or NO production inhibited with L-NAME (Figure 6B). The vasorelaxation was more sensitive in the +E group in both experimental series: logIC50 +E −6.57 ± 0.02 versus −E −5.99 ± 0.08 (P < 0.0001, n = 6) and +E −6.26 ± 0.08 versus + E L-NAME −5.78 ± 0.09 (P = 0.0009, n = 7). However, no significant change in maximum relaxation occurred. While incubation with 10 μM MONNA fully suppressed the NA-evoked tone in Cl− and Cl−-free solutions (n = 5; Figure 6C), NA could elicit tone when 1 μM MONNA was present (Figure 6D). While the maximum tone attained with 10 μM NA was reduced to ∼50% of the initial control levels when 1 μM MONNA was present, no significant difference between chloride and chloride-free conditions was seen (P = 0.61; n = 5) nor was the EC50 for NA different between the two conditions (P = 0.72).

Figure 6.

MONNA is an effective vasorelaxant agent when applied to arteries preconstricted with NA or U46619. (A) MONNA concentration-dependently relaxed mouse MSAs constricted with either 10 μM NA or 100 nM U46619 to a similar extent in chloride-containing and chloride-free solutions (n = 5). (B) Removal of the endothelium (n = 6) or inhibition of NO production with 100 μM L-NAME (n = 7) caused a rightward shift in the relaxation curves for MONNA but neither intervention prevented full relaxation (** and **** denote P ≤ 0.001 and P ≤ 0.0001 applicable for −E and L-NAME, respectively vs. paired +E control, F-test). (C) An original trace of the inhibitory effect of 10 μM MONNA (red curves) on NA-stimulated contractility in rat MSAs in the presence (upper trace) and absence of chloride (lower trace). The data are representative of five separate experiments. The scale bars apply to both graphs. The black dots indicate time points for application of 0.3–10 μM NA and stars indicate washout. (D) MONNA 1 μM suppressed NA contractility in rat MSAs in both chloride (open symbols) and chloride-free solutions (n = 5). (E) Representative traces showing the Vm before and after MONNA application in a rat MSA. Application of 1 μM MONNA had little effect while 10 μM MONNA induced a substantial hyperpolarization. Grey arrows indicate impalement and removal of the electrode respectively.

MONNA hyperpolarizes VSMC

Under resting, non-stimulated conditions, the average Vm upon impalement in rat MSA was −55.4 ± 1.7mV (n = 8 impalements from five arteries). While impaled addition of 1 μM MONNA had little effect upon the Vm (−55.9 ± 3.0mV, n = 4), the cumulative addition of 10 μM MONNA significantly hyperpolarized the Vm to −69.9 ± 2.1 mV within 5 min (Figure 6E; P < 0.0001, RM one-way anova). When the impalement was maintained up to 15 min (n = 3), the Vm reached −74.0 ± 2.0 mV although this was not significantly different from the 5 min time point. In order to rule out endothelial-derived relaxant factors such as NO, prostaglandins and EDHF in this response, we incubated four arteries in a separate experimental series with an inhibitor cocktail (100 μM L-NAME, 10 μM indomethacin, 10 μM TRAM-34 and 50 nM apamin) for ≥30 min. The vessels developed tone (0.63 ± 0.36 Nm−1) that was unaffected by exchanging the bath solution and re-introducing the inhibitors. Consequently, the resting Vm under these conditions (−36.8 ± 2.2mV) was significantly depolarized compared with the Vm without an inhibitor present (P = 0.0029, unpaired t-test). In spite of this, the application of 10 μM MONNA hyperpolarized the membrane to −56.6 ± 0.7 mV (P < 0.0001 vs. control; RM one-way anova) and the tone returned to pre-MONNA baseline levels. Application of ACh (10 μM) in the presence of 10 μM MONNA had a limited additive effect on the Vm, which was −58.1 ± 0.8 mV (nsd vs. MONNA; RM one-way anova, n = 3). The relative hyperpolarization (ΔmV) elicited by 10 μM MONNA from the initial Vm level was similar between the two conditions (P = 0.7025, unpaired t-test).

The hyperpolarization induced by MONNA is suggestive of a K+ conductance being activated. Comparison of mice with global knockout of the α-subunit of the BKCa channel against their wild-type counterparts showed no differences in the MONNA-induced vasorelaxation (Supporting Information Fig. S5).

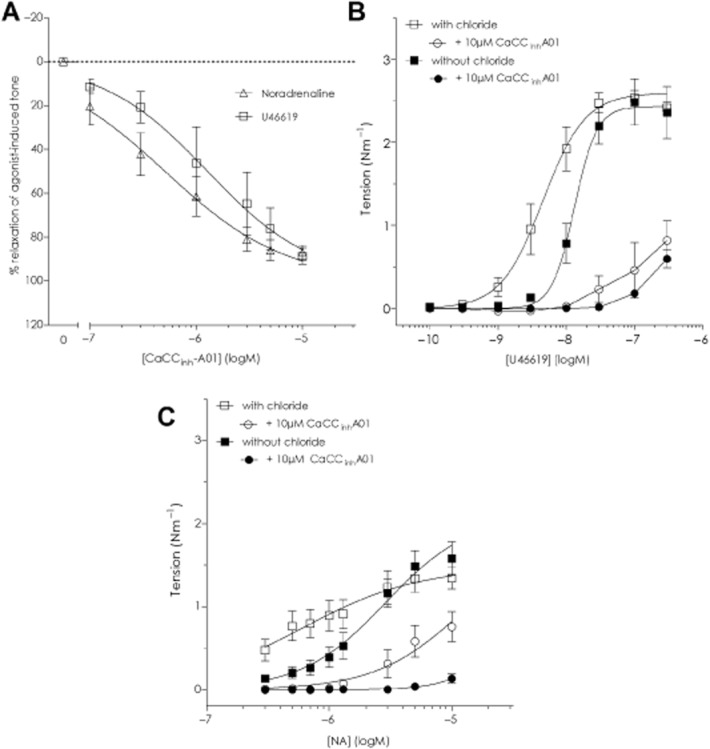

CaCCinh-A01

We tested CaCCinh-A01 upon NA- and U46619-stimulated constrictions in mouse MSA in the presence of chloride and observed an equivalent relaxation (Figure 7A): CaCCinh-A01 logIC50 −6.29 ± 0.09 against NA and −5.89 ± 0.10 for U46619 (n = 4). The CCRCs to NA and U46619 were significantly inhibited by 10 μM CaCCinh-A01 (Figure 7B and C). The U46619 curves were suppressed by CaCCinh-A01 to a similar extent with (n = 8) and without chloride (n = 5; Figure 7B), while the NA curve was fully suppressed within the concentration range of NA tested in chloride-free solution (n = 4) with some tension generated in the presence of chloride (n = 8; Figure 7C). The chloride-independent action of CaCCinh-A01 was not investigated further.

Figure 7.

The inhibitor CaCCinh-A01 has strong vasorelaxant properties irrespective of a chloride gradient in resistance arteries. (A) CaCCinh-A01, 10 μM, concentration-dependently relaxed NA- and U46619-constricted mouse mesenteric resistance arteries. (B) CaCCinh-A01 inhibited the U46619 concentration–response curve in mouse MSAs in chloride-containing (n = 9) or chloride-free (n = 5) solutions. (C) The NA concentration–response curve in mouse MSAs was also inhibited by CaCCinh-A01 under both conditions (n = 4 without chloride, n = 8 with chloride).

Discussion and conclusions

This study demonstrates that the putative TMEM16A inhibitors T16Ainh-A01, CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA induce vasorelaxation of small resistance arteries under experimental conditions where the transmembrane chloride gradient has been eliminated and chloride conductances cannot participate in Vm changes. This study corroborates the vasorelaxant activity of T16Ainh-A01 and demonstrates for the first time a similar activity for CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA but challenges the definition of these compounds as selective inhibitors of the TMEM16A-related CaCC. Furthermore, T16Ainh-A01 was demonstrated to inhibit VDCCs in A7r5 cells, while MONNA hyperpolarized the membrane of resistance artery VSMC independently of endothelial mediators, presumably via direct opening of a potassium channel.

In the present study, rodent resistance vessels were constricted with either NA, U46619 or elevated extracellular potassium and we have tested inhibitors both in the presence of extracellular chloride and during prolonged substitution with aspartate, as the replacement of extracellular chloride with an impermeant anion has been demonstrated to cause a rapid (5–20 min) depletion of intracellular chloride in smooth muscle (Aickin and Brading, 1983; Davis et al., 1997). An equivalent relaxation was induced by T16Ainh-A01 when applied to NA- or U46619-induced constrictions, similar to that previously reported for vascular smooth muscle (Davis et al., 2013). However, we observed that T16Ainh-A01 was equally effective in relaxing vessels irrespective of the presence of chloride, an observation which puts the mechanistic action of this inhibitor as a selective chloride channel inhibitor in doubt. The similar IC50 values calculated from the NA and U46619 experiments suggest that the inhibitor is not a receptor blocker but is interfering with some common, chloride-independent mechanism(s) past the receptor-coupling level. Cumulative concentration–response curves constructed to NA and U46619 under normal and chloride-free conditions demonstrated that T16Ainh-A01 had surprisingly little effect upon tension development given that the same concentrations of the inhibitor effectively relaxed preconstricted vessels. The curves shifted rightward in the presence of T16Ainh-A01, suggesting a change in agonist sensitivity consistent with inhibition of CaCCs; however, an equivalent reduction in sensitivity was also observed in a chloride-free solution. On the basis of these observations, we conclude that T16Ainh-A01 can alter vascular tone, but most effectively under depolarized conditions, and that T16Ainh-A01 is effective even when intracellular chloride is depleted and chloride conductances have a negligible contribution to membrane depolarization. Thus, changes in contractility induced by this compound cannot be interpreted as the result of inhibition of chloride conductance.

If the effect of T16Ainh-A01 was not inhibition of Cl− conductance via channel closure, then the remaining possibilities include stimulation of endothelial-derived relaxant factors or direct VSMC membrane changes such as K+ channel opening and Ca2+ channel closure. While the endothelium, and in particular NO, appear to enhance sensitivity to the inhibitor, their absence did not prevent full relaxation to T16Ainh-A01 suggesting the primary target is the VSMC. We investigated this firstly by testing the effect of T16Ainh-A01 on the Vm of VSMC in combination with force changes. Under resting conditions, vessels in Cl−-free were more depolarized than those in Cl−-containing solution (Nilsson et al., 1998) and the maximum depolarization to NA was reduced, similar to previous observations (Large, 1984). However, T16Ainh-A01 application caused a similar concentration-dependent hyperpolarization in Cl− and Cl−-free conditions, which preceded the vasorelaxation. At maximum vasorelaxation, the Vm did not hyperpolarize further than the initial resting Vm level prior to NA application, suggesting that K+ conductances are not activated by the inhibitor. A similar lack of K+ channel activation was concluded by Davis et al. based on their observation that T16Ainh-A01 was still effective in relaxing mouse aorta in the presence of paxilline (BKCa), glibenclamide (KATP) and linopirdine (KV7). Thus, part of the vasorelaxant mechanism might occur through closure of VDCC on the VSMC membrane. It is well known that elevation of extracellular K+ depolarizes the membrane and increases Ca2+ influx through VDCC on the sarcolemma with consequent Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and contraction. In contrast to the previous lack of T16Ainh-A01 effect upon 60 mM K-PSS contractions (Davis et al., 2013), we observed that T16Ainh-A01 applied to a stable 60 mM constriction did lower tension. We confirmed, using fura-2 loaded arteries, that the loss of 60 mM K+-evoked tone was due to a lowering of intracellular Ca2+. Furthermore, the inhibitor reversed tone and lowered Ca2+ in the absence of Cl−. We can only speculate as to the reason for the difference between our findings and those of Davis and colleagues, but what is not entirely clear from their study is whether T16Ainh-A01 was applied prior to the K+-constriction or after tone was established. If the inhibitor was applied before K+, it could be expected, based on our current observations regarding potency difference when applied to resting or depolarized conditions, that T16Ainh-A01 could have a minimal effect. Alternatively, the aorta may simply be less sensitive than the resistance arteries tested here. To investigate whether T16Ainh-A01 has inhibitory activity against VDCC, we investigated L-type Ca2+ currents in A7r5 cells, a widely utilized VSMC line for studying L-type VDCC. We found that 1 μM T16Ainh-A01 inhibited almost all inward current, although these experiments provided a lower IC50 for block of the VDCC in A7r5 by T16Ainh-A01 than that calculated for vasorelaxation of arteries. This finding suggests that the vasorelaxant effect of T16Ainh-A01 in rodent resistance arteries could have a component of reduced Ca2+ influx via inhibition of VDCC; however, this must be substantiated for T16Ainh-A01 against the native VSMC L-type current.

We report here a disparity in the vasorelaxant efficacy of T16Ainh-A01 when examined under depolarized conditions (i.e. maximum agonist constriction or depolarized with elevated K+o) compared with resting, non-stimulated conditions. This finding suggests that the mode of action of T16Ainh-A01 is voltage-dependent, with the affinity of the inhibitor for its target being highest under depolarized conditions, similar to that of verapamil against the VDCC. We did not, however, observe a voltage-dependent action of T16Ainh-A01 against the VDCC in A7r5 cells. In terms of ICl(Ca), T16Ainh-A01 has been reported to inhibit ICl(Ca) equally at all voltages tested (Namkung et al., 2011; Bradley et al., 2014) and to have a voltage-dependent effect (Reyes et al., 2015). Recent evidence using mutagenesis of Xenopus tropicalis TMEM16A suggests that T16Ainh-A01 interacts within the pore region of the channel (Reyes et al., 2015). Could the voltage-dependent effect of T16Ainh-A01 in the absence of Cl−, therefore, still underlie its affinity for the channel? TMEM16A has been reported to have Na+ permeability, although the PNa/PCl for ICl(Ca) is low with values of 0.03–0.1 for maximal current stimulation with μM [Ca2+] (Qu and Hartzell, 2000; Yang et al., 2008; 2012,; Jung et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2015). Accordingly, the voltage-dependent effect of T16Ainh-A01 in Cl−-free solution could reflect inhibition of a TMEM16A Na+ conductance. One must, however, consider that ionic permeability and conductance are typically determined relative to Cl− in asymmetrical or symmetrical substitutions and do not necessarily reflect the channel's activity in the environment we impose upon it with zero Cl−o (aspartate) and low Cl−i. Whether a cation conductance is possible via TMEM16A under our experimental conditions is unknown, but if so the contribution would probably be minor in comparison with the dominant non-selective cation currents and VDCC present in VSMC. Further studies are needed to explore the difference in T16Ainh-A01 potency with Vm and to define what molecular mechanism may underlie this observation.

MONNA has been demonstrated to inhibit the endogenous ICl(Ca) in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Oh et al., 2013), known to be carried by xANO1 (Schroeder et al., 2008), as well as human ANO1 heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells with no apparent inhibition of expressed bestrophin-1, ClC2 or CFTR (Oh et al., 2013). We report here that MONNA, like T16Ainh-A01, can induce vasorelaxation and at 10 μM completely inhibits agonist-induced constriction due to ≈15–20 mV (endothelium-independent) hyperpolarization. However, at 1 μM, MONNA did not affect the resting Vm and NA-stimulated contractility was possible, with no suppression in the Cl−-free condition. This suggests that MONNA may have an inhibitory, concentration-dependent profile with overlapping CaCC inhibition and K+ channel activation. Resistance arteries from mice lacking the α-subunit of BKCa (Sausbier et al., 2005) relaxed equally well as their matched wild types suggesting that this channel is not responsible. The K+ channel(s) involved and the mode of stimulation warrant further investigation.

Despite strong supportive evidence for inhibition of TMEM16A currents by the inhibitors tested here (Davis et al., 2013; Oh et al., 2013; Bradley et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014), our data contribute to a growing pool of evidence that question the selectivity of these new small molecule inhibitors. Indeed, recent work has demonstrated that CaCCinh-A01 attenuates TMEM16A-induced proliferation in cancer cell lines because of targeted degradation of the protein rather than inhibition of ICl(Ca): T16Ainh-A01 had no such effect on protein levels (Bill et al., 2014). Studies have also determined that the concentrations necessary for Cl− channel inhibition affect cell activity by other mechanisms. For example, Kucherenko et al. found in human red blood cells that CaCCinh-A01 reduces BKCa channel activity, lowers intracellular Ca2+ and induces phosphatidylserine exposure by a Ca2+-independent mechanism (Kucherenko et al., 2013). Non-selective actions of T16Ainh-A01 and CaCCinh-A01 on intracellular Ca2+ were also observed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines (Sauter et al., 2015) and in HEK293 cells (Kunzelmann et al., 2012). T16Ainh-A01 conversely had no effect on basal levels and inhibited the Ca2+ increase by ∼25% (Sauter et al., 2015). Additionally, T16Ainh-A01 was observed to have anti-proliferative effects in cell lines with very low TMEM16A expression (Sauter et al., 2015).

The precise site(s) of action of T16Ainh-A01, CaCCinh-A01 and MONNA remain to be determined. We have demonstrated that their vasorelaxant effect does not require chloride but we cannot yet pinpoint the precise mechanism(s) that underlie the vasorelaxant effect of these inhibitors. We are thus left to speculate ‘what do they do?’. We observed that T16Ainh-A01 inhibits Ca2+ influx through VDCC in A7r5 cells: it is reasonable to suggest that a similar activity against VDCC in native VSMC could be part of the T16Ainh-A01 profile. MONNA can induce membrane hyperpolarization, suggesting a K+ channel is involved; however, the identity of this channel is as yet unknown. A functional NO release appears to enhance the sensitivity of relaxation to both compounds but the vasorelaxation is not dependent upon the endothelium per se. Presently, we cannot exclude the possibility that reduced release from Ca2+ stores, changes in Ca2+-sensitivity or combinations of these possibilities in the VSMC are also occurring with either MONNA or T16Ainh-A01. In spite of convincing evidence that these inhibitors are not chloride channel specific, further studies are needed to clarify precisely how these inhibitors interact with and affect VSMC membranes as well as intracellular signalling.

Despite the rigorous standards applied to antibodies to provide proof of their specificity using knockout models, inhibitors of specific channels and conductances have not yet been scrutinized in a similar fashion. Mouse models lacking TMEM16A, either globally or in VSMCs, have been generated. In future studies, inhibitors purporting to be specific for the TMEM16A/CaCC must be tested in tissues lacking the TMEM16A protein to determine how these compounds alter vascular reactivity in a chloride- or TMEM16A-independent fashion.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jørgen Andresen for skilled technical assistance. The authors express their gratitude to Professor Christian Aalkjaer for scientific discussions. Professors C. Justin Lee and Eun Joo Rho from Korea Institute of Science and Technology are gratefully acknowledged for providing MONNA. Professor Peter Ruth from Universität Tübingen is gratefully acknowledged for provision of the BKCa knockout and wild-type animals. This research was not funded by a specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Glossary

- CaCC

calcium-activated chloride channel

- IBa

barium current

- ICl(Ca)

calcium-activated chloride current

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- MSA

mesenteric artery

- NA

noradrenaline

- VDCCs

voltage-dependent calcium channels

- Vm

membrane potential

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Author contributions

D. M. B. B. designed the research study. D. M. B. B., S. K., A. B. J. and V. M. M. performed the research. D. M. B. B., S. K., V. M. M. and K. E. A. analysed and interpreted the data. D. M. B. B. and K. E. A. wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Rat mesenteric arteries pre-constricted with 10μM noradrenaline are readily relaxed by 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (A and B) or 100 μM T16Ainh-A01 (C and D). The inhibitor T16Ainh-A01 is as effective in solutions containing chloride (A and C) as in the absence of extracellular chloride (B and D). The vehicle (DMSO) has no significant effect in either condition. Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graphs; ***P < 0.001 (two-way anova; Bonferroni's post test).

Figure S2 Mouse mesenteric small arteries constricted with 100 nM U46619 are concentration-dependently relaxed by T16Ainh-A01 but not DMSO (A). Pre-incubation with 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 causes a rightward shift in the U46619 cumulative concentration–response curve compared with control but has a markedly smaller impact on agonist-induced tone than observed when applied to a maximally constricted vessel as in panel A. Data represent mean ± SEM for experiments performed in chloride-containing solution.

Figure S3 Successive noradrenaline (NA) cumulative concentration–response experiments performed on rat mesenteric resistance arteries display no significant effect of time (A) or the vehicle DMSO (B) when in normal physiological solution (PSS). Repeated NA curves on mouse mesenteric small arteries in normal physiological solution are not significantly different with time (C). Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graphs.

Figure S4 T16Ainh-A01 does not stimulate muscarinic receptors to elicit vasorelaxation. Rat mesenteric arteries precontracted with 10 μM noradrenaline were exposed to increasing concentrations of T16Ainh-A01 in the presence and absence of 1 μM atropine (in chloride-containing solution). No significant difference in logIC50 (control −5.71 ± 0.08 vs. atropine −5.74 ± 0.08, P = 0.7465) or maximum relaxation were observed (control 97.5 ± 0.7% vs. atropine 98.1 ± 0.8%, P = 0.8399). Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graph.

Figure S5 Vasorelaxation induced by MONNA in mouse mesenteric arteries does not require the BKCa channel. No significant difference in logIC50 (WT −5.58 ± 0.02 vs. BKCa−/− −5.47 ± 0.10, P = 0.1537) or maximum relaxation were observed (WT 94.3 ± 0.6% vs. BKCa−/− 91.8 ± 3.8%, P = 0.4369). Arteries were maintained in chloride-containing solution. Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graph.

References

- Abd El-Rahman RR, Harraz OF, Brett SE, Anfinogenova Y, Mufti RE, Goldman D, et al. Identification of L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in rat cerebral arteries: role in myogenic tone development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H58–H71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00476.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aickin CC, Brading AF. Towards an estimate of chloride permeability in the smooth muscle of guinea-pig vas deferens. J Physiol. 1983;336:179–197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1607–1651. doi: 10.1111/bph.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A, Hall ML, Borawski J, Hodgson C, Jenkins J, Piechon P, et al. Small Molecule-facilitated Degradation of ANO1 Protein: a new targeting approach for anticancer therapeutics. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11029–11041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.549188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedtkjer DM, Matchkov VV, Boedtkjer E, Nilsson H, Aalkjaer C. Vasomotion has chloride-dependency in rat mesenteric small arteries. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Fedigan S, Webb T, Hollywood MA, Thornbury KD, McHale NG, et al. Pharmacological characterization of TMEM16A currents. Channels. 2014;8:308–320. doi: 10.4161/chan.28065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz B, Faria D, Schley G, Schreiber R, Eckardt KU, Kunzelmann K. Anoctamin 1 induces calcium-activated chloride secretion and proliferation of renal cyst-forming epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1058–1067. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, et al. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield AR, Harper AA. Chloride in smooth muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;74:175–221. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam VS, Boedtkjer DM, Nyvad J, Aalkjaer C, Matchkov V. TMEM16A knockdown abrogates two different Ca(2+)-activated Cl(−) currents and contractility of smooth muscle in rat mesenteric small arteries. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1391–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1382-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AJ, Shi J, Pritchard HA, Chadha PS, Leblanc N, Vasilikostas G, et al. Potent vasorelaxant activity of the TMEM16A inhibitor T16A(inh) -A01. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:773–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JP, Harper AA, Chipperfield AR. Stimulation of intracellular chloride accumulation by noradrenaline and hence potentiation of its depolarization of rat arterial smooth muscle in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:639–642. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente R, Namkung W, Mills A, Verkman AS. Small-molecule screen identifies inhibitors of a human intestinal calcium-activated chloride channel. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:758–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest AS, Joyce TC, Huebner ML, Ayon RJ, Wiwchar M, Joyce J, et al. Increased TMEM16A-encoded calcium-activated chloride channel activity is associated with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C1229–C1243. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00044.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Nam JH, Park HW, Oh U, Yoon JH, Lee MG. Dynamic modulation of ANO1/TMEM16A HCO3(-) permeability by Ca2+/calmodulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:360–365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211594110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucherenko Y, Wagner-Britz L, Bernhardt I, Lang F. Effect of chloride channel inhibitors on cytosolic Ca2+ levels and Ca2+-activated K+ (Gardos) channel activity in human red blood cells. J Membr Biol. 2013;246:315–326. doi: 10.1007/s00232-013-9532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, Kmit A, Jantarajit W, Martins JR, Faria D, et al. Expression and function of epithelial anoctamins. Exp Physiol. 2012;97:184–192. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA. The effect of chloride removal on the responses of the isolated rat anococcygeus muscle to alpha 1-adrenoceptor stimulation. J Physiol. 1984;352:17–29. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang H, Huang D, Qi J, Xu J, Gao H, et al. Characterization of the effects of Cl(−) channel modulators on TMEM16A and bestrophin-1 Ca(2+) activated Cl(−) channels. Pflugers Arch. 2014;467:1417–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Tamuleviciute A, Tammaro P. TMEM16A/anoctamin 1 protein mediates calcium-activated chloride currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:2305–2314. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen A, Schakman O, Yerna X, Dessy C, Morel N. Myosin light chain kinase controls voltage-dependent calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1377–1389. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone A, Eisenman ST, Strege PR, Yao Z, Ordog T, Gibbons SJ, et al. Inhibition of cell proliferation by a selective inhibitor of the Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channel, Ano1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ Res. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung W, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium-activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2365–2374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson H, Videbæk LM, Toma C, Mulvany MJ. Interactions between membrane potential and intracellular calcium concentration in vascular smooth muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:559–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Hwang SJ, Jung J, Yu K, Kim J, Choi JY, et al. MONNA, a potent and selective blocker for transmembrane protein with unknown function 16/anoctamin-1. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:726–735. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.087502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parai K, Tabrizchi R. Effects of chloride substitution in isolated mesenteric blood vessels from Dahl normotensive and hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;46:105–114. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000164090.04069.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cornejo P, De Santiago JA, Arreola J. Permeant anions control gating of calcium-dependent chloride channels. J Membr Biol. 2004;198:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0659-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Hartzell HC. Anion permeation in Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channels. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:825–844. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JP, Huanosta-Gutierrez A, Lopez-Rodriguez A, Martinez-Torres A. Study of permeation and blocker binding in TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels. Channels (Austin) 2015;9:88–95. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2015.1027849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanenko VG, Catalan MA, Brown DA, Putzier I, Hartzell HC, Marmorstein AD, et al. Tmem16A encodes the Ca2+-activated Cl- channel in mouse submandibular salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12990–13001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JM. Sodium-potassium-chloride cotransport. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:211–276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sausbier M, Arntz C, Bucurenciu I, Zhao H, Zhou XB, Sausbier U, et al. Elevated blood pressure linked to primary hyperaldosteronism and impaired vasodilation in BK channel-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:60–68. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156448.74296.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter DR, Novak I, Pedersen SF, Larsen EH, Hoffmann EK. ANO1 (TMEM16A) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) Pflugers Arch. 2015;467:1495–1508. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1598-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Xia Y, Paudel O, Yang XR, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channel in pulmonary arterial myocytes: a mechanism contributing to enhanced vasoreactivity. J Physiol. 2012;590:3507–3521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Gatewood C, Neeb ZP, Bulley S, Adebiyi A, Bannister JP, Leo MD, et al. TMEM16A channels generate Ca(2)(+)-activated Cl(−) currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1819–H1827. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00404.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubosaka Y, Murata T, Kinoshita K, Yamada K, Uemura D, Hori M, et al. Halichlorine is a novel L-type Ca(2+) channel inhibitor isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai Kadota. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;628:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Kim A, David T, Palmer D, Jin T, Tien J, et al. TMEM16F forms a Ca2+-activated cation channel required for lipid scrambling in platelets during blood coagulation. Cell. 2012;151:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Rat mesenteric arteries pre-constricted with 10μM noradrenaline are readily relaxed by 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 (A and B) or 100 μM T16Ainh-A01 (C and D). The inhibitor T16Ainh-A01 is as effective in solutions containing chloride (A and C) as in the absence of extracellular chloride (B and D). The vehicle (DMSO) has no significant effect in either condition. Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graphs; ***P < 0.001 (two-way anova; Bonferroni's post test).

Figure S2 Mouse mesenteric small arteries constricted with 100 nM U46619 are concentration-dependently relaxed by T16Ainh-A01 but not DMSO (A). Pre-incubation with 10 μM T16Ainh-A01 causes a rightward shift in the U46619 cumulative concentration–response curve compared with control but has a markedly smaller impact on agonist-induced tone than observed when applied to a maximally constricted vessel as in panel A. Data represent mean ± SEM for experiments performed in chloride-containing solution.

Figure S3 Successive noradrenaline (NA) cumulative concentration–response experiments performed on rat mesenteric resistance arteries display no significant effect of time (A) or the vehicle DMSO (B) when in normal physiological solution (PSS). Repeated NA curves on mouse mesenteric small arteries in normal physiological solution are not significantly different with time (C). Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graphs.

Figure S4 T16Ainh-A01 does not stimulate muscarinic receptors to elicit vasorelaxation. Rat mesenteric arteries precontracted with 10 μM noradrenaline were exposed to increasing concentrations of T16Ainh-A01 in the presence and absence of 1 μM atropine (in chloride-containing solution). No significant difference in logIC50 (control −5.71 ± 0.08 vs. atropine −5.74 ± 0.08, P = 0.7465) or maximum relaxation were observed (control 97.5 ± 0.7% vs. atropine 98.1 ± 0.8%, P = 0.8399). Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graph.

Figure S5 Vasorelaxation induced by MONNA in mouse mesenteric arteries does not require the BKCa channel. No significant difference in logIC50 (WT −5.58 ± 0.02 vs. BKCa−/− −5.47 ± 0.10, P = 0.1537) or maximum relaxation were observed (WT 94.3 ± 0.6% vs. BKCa−/− 91.8 ± 3.8%, P = 0.4369). Arteries were maintained in chloride-containing solution. Data represent mean ± SEM for the number of experiments stated on the graph.