Background: A lateral helix in the membrane arm of Complex I was proposed to function as a piston during proton translocation.

Results: Cross-linking the lateral helix to other subunits did not impair proton translocation.

Conclusion: The evidence does not support a piston-type role for the lateral helix.

Significance: Energy transduction by Complex I must involve communication through other structural features.

Keywords: complex I, cysteine-mediated cross-linking, membrane energetics, membrane protein, protein cross-linking, proton transport, methanethiosulfonate

Abstract

Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) is a multisubunit, membrane-bound enzyme of the respiratory chain. The energy from NADH oxidation in the peripheral region of the enzyme is used to drive proton translocation across the membrane. One of the integral membrane subunits, nuoL in Escherichia coli, has an unusual lateral helix of ∼75 residues that lies parallel to the membrane surface and has been proposed to play a mechanical role as a piston during proton translocation (Efremov, R. G., Baradaran, R., and Sazanov, L. A. (2010) Nature 465, 441–445). To test this hypothesis we have introduced 11 pairs of cysteine residues into Complex I; in each pair one is in the lateral helix, and the other is in a nearby region of subunit N, M, or L. The double mutants were treated with Cu2+ ions or with bi-functional methanethiosulfonate reagents to catalyze cross-link formation in membrane vesicles. The yields of cross-linked products were typically 50–90%, as judged by immunoblotting, but in no case did the activity of Complex I decrease by >10–20%, as indicated by deamino-NADH oxidase activity or rates of proton translocation. In contrast, several pairs of cysteine residues introduced at other interfaces of N:M and M:L subunits led to significant loss of activity, in particular, in the region of residue Glu-144 of subunit M. The results do not support the hypothesis that the lateral helix of subunit L functions like a piston, but rather, they suggest that conformational changes might be transmitted more directly through the functional residues of the proton translocation apparatus.

Introduction

Complex I, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, is the largest component of the mammalian mitochondrial electron transport chain, where it appears to contain 44 unique polypeptide chains (Refs. 1 and 2; for reviews, see Refs. 3 and 4). Its oxidation of NADH serves three purposes; 1) it replenishes the supply of NAD+ needed for the citric acid cycle, 2) it feeds respiration by reducing ubiquinone, and 3) it contributes to generation of the proton motive force through translocation of hydrogen ions across the membrane. Complex I is also a source of reactive oxygen species (5, 6) such as superoxide, and in mammalian cells it is connected to apoptotic pathways (7, 8).

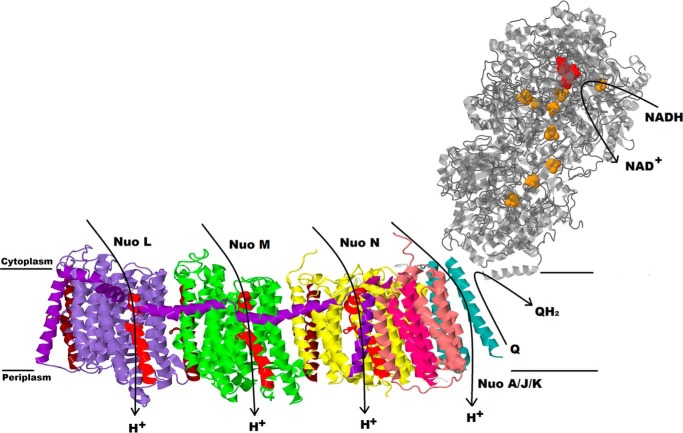

Crystal structures of yeast and mammalian mitochondrial Complex I have been solved in recent years (9–11). These structures have confirmed the close relationship between the mitochondrial and bacterial versions of the enzyme, which were solved earlier (12–14). Sazanov and co-workers (15) have determined the structures of Complex I from Thermus thermophilus and of a six-subunit, membrane fragment from Escherichia coli (16). The crystal structures confirmed the L-shaped form first seen by microscopy (17, 18). One arm is found in the membrane, whereas a peripheral arm extends at an angle of ∼120° into the aqueous medium (Fig. 1). The peripheral arm contains all the prosthetic groups, including one flavin (FMN) at the NADH binding site, and eight Fe-S clusters. Some bacterial versions of Complex I contain an additional Fe-S cluster that is not thought to be part of the main pathway (19). The membrane arm of the mitochondrial enzyme contains all of the seven mitochondria-encoded subunits, and the bacterial enzyme contains homologs of each. In bacteria, the membrane arm is composed entirely of these subunits. The ubiquinone binding site is formed by subunits at the junction of the two arms.

FIGURE 1.

Overall architecture of Complex I. The membrane domain is from E. coli Complex I, PDB file 3rko, and the peripheral domain is from T. thermophilus Complex I, PDB code 4hea. FMN in the peripheral arm is in red, and nine iron sulfur clusters are in orange. Two broken helices in each subunit LMN are indicated as TM7 in red and TM 12 in brown.

In the E. coli enzyme, all subunits are encoded by the nuo operon (20). The membrane subunit H (325 amino acids) forms the primary interface with the peripheral arm and contributes to the quinone binding region. Also near this interface are the three smaller subunits, A (147 amino acids), J (184 amino acids), and K (100 amino acids), which are intertwined with each other to some extent. Moving out from the interface are the three largest membrane subunits, which resemble proteins from a bacterial cation antiporter complex. These subunits, N (485 amino acids (aa)), M (509 aa), and L (613 aa) are also homologous to each other, with a core of 14 TM2 helices (16). Two of the helices, TM7 and TM12, are formed by discontinuous helical segments, which are broken in the middle of the membrane, and referred to as the “broken” helices, e.g. TM7a and TM7b. Furthermore, each of the broken helices in each of the subunits is related to the other by internal symmetry that also includes four additional TM helices. For example, TM4–8 is homologous to TM9–13. These elements are related to each other by a rotation of 180° such that they have opposite orientations in the membrane. From crystal structure analysis (16) and molecular dynamics (21), it is thought that TM7b and TM12b contribute to “half-channels” that connect the surface of the membrane to the middle of the membrane. The half-channels are proposed to be connected by a central channel through the middle of each subunit (15, 16). A series of mutagenic studies has revealed essential amino acids that lie along these proposed pathways (22–29).

An additional unusual structural feature is formed by the last 125 amino acids of subunit L. Two TM helices, 15 and 16, are bridged by ∼75 amino acids that are primarily α-helical and arranged laterally along the membrane surface. This lateral helix contacts homologous segments of subunits L, M, and N, primarily at the broken helix TM7b in each. It also contacts the short and highly conserved loop between TM9 and -10 at the cytoplasmic surface. TM16, at the extreme C terminus of subunit L, is in contact with subunits J, K, and N. It has been proposed that the lateral helix functions like a piston to coordinately open the proton channels through contact with each TM7b (10, 12, 16, 30).

To test this hypothesis we engineered a series of cysteine pairs so that the lateral helix could be cross-linked to contact sites in subunits L, M, and N. At sites of close contact disulfide bonds were formed, and at longer distances cross-linking was mediated by bifunctional methanethiosulfonate reagents. The results did not support a piston-like mechanism for the lateral helix.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

The QuikChange Mutagenesis kit was from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA). DNA Miniprep kits were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) and Thermo Scientific, Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA). The QIAEXII-Agarose Gel Extraction kit and QIAquick Gel Extraction kit were from Qiagen. Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were from New England BioLabs (Beverly, MA). MTS (methanethiosulfonate) cross-linking reagents, M2M (1,2-ethanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate), M3M (1,3-propanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate), M4M (1,4-butanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate), and M6M (1,6-hexanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate) were from Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc. (Toronto, Canada). Immunoblot polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, p-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT), 5-bromo-4-chloro-indolphosphate p-toluidine salt (BCIP), SDS-polyacrylamide gels, low range molecular weight standards, and the DC protein assay kit were from Bio-Rad. 9-Amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine (ACMA) was from Invitrogen. The polyclonal antibodies against E. coli complex I subunits L and M were prepared by Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). These antibodies were raised in rabbits against peptide QTYSQPLWTWMSVGD (corresponding to residues 58–72) in subunit L and peptide GKAKSQIASQELPGM (corresponding to residues 446–460) in subunit M and were described previously (22). Subunit N was detected by the monoclonal rat anti-HA (high affinity) antibody from Roche Applied Science. Other chemicals, including deamino-NADH, capsaicin, carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), and potassium ferricyanide, were from Sigma. Oligonucleotides for mutagenesis and sequencing were synthesized by Eurofins (Huntsville, AL). DNA sequencing was performed in Lone Star Labs, Inc. (Houston, TX).

Construction of Cys-substituted Mutants

Plasmids pUC19-LMN and pUC19-L′MN (22) were used for construction of most of the cysteine mutants. A new plasmid, pUC19 L′MN-SpeI, was constructed from pUC19-L′MN for generation of mutations near the C terminus of nuoN. Both of the plasmids are 6.5 kb and contain a 3′-truncated gene for L and full-length genes for subunits M and N. They differ only in that pUC19 L′MN-SpeI contains a unique SpeI endonuclease site downstream of the nuoN gene. Initially a recognition site for Bsu36I was constructed by QuikChange mutagenesis in pUC19-L′MN, but after that enzyme proved to be problematic, the site was changed to SpeI by ligating a designed linker. Mutations constructed in L, M. or N were transferred to the expression vector, pBA400, using two unique restriction sites. The expression vector originally contained a Bsu36I site downstream of nuoN. This was changed to SpeI using the same linker, creating pBA400-SpeI. The final step in creating the pUC19-L′MN-SpeI plasmid was to move a PstI-SpeI fragment from pBA400-SpeI into the pUC19 plasmid so that nuoN contains the HA tag at the C terminus. Cysteine substitutions were initially introduced into subunit L, M, or N by QuikChange mutagenesis. Two strategies were used for generating double Cys-substituted mutants. First, plasmids containing single Cys substitutions were digested with two endonucleases, and the insert was ligated in the vector containing the second Cys mutation, or the plasmids containing the first Cys mutations were used as the templates in QuikChange mutagenesis for creating the second Cys mutations. The double Cys mutants were transferred into plasmid pBA400 or pBA400-SpeI that contains a full size nuo operon and transformed into strain BA14 that carries a chromosomal deletion for the genes of all complex I subunits (31). The construction of the quadruple Cys substitutions started with an existing double Cys mutant. The third Cys mutation was introduced by endonucleases MfeI and AscI, and the fourth Cys mutation was obtained by QuikChange mutagenesis using the triple Cys-substituted plasmid pUC19 L′MN-SpeI as the template. Each of the doubly Cys-substituted mutants were grown on M63 minimal media agar plates with acetate to compare the growth of mutants relative to the wild type. Acetate plates contained 1.36% KH2PO4, 0.2% (NH4)2SO4, 0.05% FeSO4·7H2O, 1.5% agar, 0.02% MgSO4, 0.001% vitamin B1, and 0.2% potassium acetate, pH 7.0. Growth was evaluated by visual inspection after 48–72 h at 37 °C.

Growth and Membrane Preparation

All mutants and wild type E. coli cells were grown in Rich media (3% Tryptone, 1.5% yeast extract, 0.15% NaCl, and 1% (v/v) glycerol) at 30 °C, and the cultures were harvested at A600 = ∼1.2. Cells were suspended in TMG buffer (50 mm Tris·HCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) or TMG-acetate buffer (50 mm Tris·acetate, 5 mm magnesium acetate, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) and passed through a French press at 14,000 p.s.i. Membrane vesicles were prepared as described previously (22, 31).

Cross-linking with Cu2+

Membrane vesicles in TMG buffer were incubated with 1.5 mm CuCl2 at 4 °C for 1 h. The cross-linking reaction was terminated by the addition of 15 mm Na2EDTA and 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide and was incubated at 4 °C for 10 min. Membrane vesicles were mixed with an equal volume sample buffer (350 mm Tris·HCl, 10% SDS, 30% glycerol, 0.12 mg/ml bromphenol, pH 6.8) and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h before analyzing by SDS electrophoresis.

Cross-linking with MTS Reagents

A 25 mm MTS reagent solution was made in dimethyl sulfoxide immediately before cross-linking. Membrane vesicles in TMG-acetate buffer were treated with 250 μm MTS reagents and incubated at 4 °C for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 mm Na2EDTA at 4 °C for 15 min. Membrane vesicles were incubated with an equal volume of sample buffer for 1 h before analyzing by SDS electrophoresis. The procedures were adapted from Fillingame and co-workers (32, 33).

SDS Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

40 μg of membrane samples were run on 12% acrylamide gels at 150 V for 1 h and then transferred to PVDF membranes by applying 100 V for 1 h in transfer buffer (25 mm Tris, 192 mm glycine, and 20% methanol, pH 8.3). The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBS/Tween 20 (20 mm Tris, 500 mm NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.5) for 1 h and then washed 3 times with TBS/Tween 20. The PVDF membrane was incubated with rabbit custom antibodies diluted 1:5,000 for subunit L, 1:10,000 for subunit M or rat anti-HA serum, and 1:5,000 for subunit N at room temperature for at least 2 h. After washing 3 times with TBS/Tween 20, the blot was incubated with goat anti-rabbit or anti-rat IgG-alkaline phosphatase (diluted 1:1000) for 1 h. After three more washings, the color was developed with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and p-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride in developing buffer (0.1 m Tris, 0.5 mm MgCl2, pH 9.5) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ software (rsb.info.nih.gov). Blots shown are representative of two or three blots in total. Yields of cross-linking were estimated from the disappearance of the bands for isolated L, M, or N subunits after treatment relative to the untreated samples. Values shown fall with a range of ±15%.

Enzymatic Assays

The activity assays were conducted according to the methods described previously (22, 31). In brief, deamino-NADH oxidase activity assays were started with 0.25 mm deamino-NADH (extinction coefficient 6.22 mm−1 cm−1), and the absorbance was monitored at 340 nm for 2 min. Proton translocation assays were conducted by measuring the fluorescence quenching of the acridine dye ACMA as a ΔpH indicator using excitation and emission wave lengths of 410 and 490 nm, respectively, using a PTI QuantaMaster 40 spectrofluorometer. Both deamino-NADH oxidase activity assays and proton translocation assays were conducted by using 150 μg/ml protein membrane in deamino buffer (50 mm MOPS, 10 mm MgCl2, pH 7.3) at room temperature. The 1 μm uncoupler FCCP from a 1 mm ethanol stock was added to eliminate the buildup of a proton gradient during NADH oxidase assays. For proton translocation assays, ACMA was added to 1 μm, whereas other concentrations were the same as for oxidase assays. Ferricyanide reductase assays were conducted according to the published procedure (34) at room temperature, and the absorbance was monitored at 410 nm for 2 min in buffer containing 10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm K3FeCN6, and 10 mm KCN. Ferricyanide was used as the terminal electron acceptor (extinction coefficient of 1.0 mm−1 cm−1). The assays were started with 80 μg/ml protein membrane and 0.15 mm deanimo-NADH.

Structural Analysis

Protein Data Bank code 3rko (16) was used for the design of mutations and for structural analysis. It includes subunits A, J, K, L, M, and N of the membrane arm of the E. coli enzyme and lacks subunit H of the membrane arm and all of the subunits of the peripheral arm, B, CD, E, F, G, and I. Analysis of subunit interactions was facilitated by the Contact Map Analysis module (35) of the SPACE suite (36) of tools. Seven endogenous cysteine residues exist at the following locations: 149 in TM5 (L), 356 in TM11 (L), 377 in TM12a (L), 17 in TM1 (M), 104 in TM3 (M), 359 in TM11 (M), and 88 in TM3 (N). None of these residues is in proximity to any of the cysteines introduced into the lateral helix, the closest pair being at least 20 Å apart. The MTS cross-linkers are expected to bridge only up to 10–15 Å (32). None of the endogenous or introduced cysteines are located in or near the sequences used to generate the antibodies for subunit L (58–72) or subunit M (446–460).

Results

Construction of Cross-links with the Lateral Helix

In an attempt to constrain the lateral helix of nuoL by chemical cross-linking, 11 pairs of cysteine mutations were introduced into the membrane subunits of Complex I. The double mutants were constructed at nine distinct sites in nuoL (7 in the lateral helix and 2 in TM16), in conjunction with one site in nuoL outside the lateral helix, four distinct sites in nuoM, and two in nuoN. The pairs of cysteine mutations are depicted in Fig. 2 and are listed in Table 1. The sites were selected such that the α-carbon distances were in the range of 4–7 Å, optimal for disulfide formation, or distances of 10–17 Å for cross-linking by MTS reagents. The mutations were transferred to the low copy expression vector pBA400 and were expressed in the nuo deletion strain BA14. All double mutants grew on minimal plates (M63) supplemented with acetate as the sole carbon source, similar to the wild type. Membrane vesicles were prepared and assayed for NADH oxidase activity and for NADH ferricyanide reductase activity using deamino-NADH. The results of the activity assays are shown in Table 1. The ferricyanide reductase activities ranged from 91% to 132% that of the wild type value, indicating that assembly of Complex I is near normal in all. The NADH oxidase values ranged from 52% to 164% that of wild type or 57% to 146% when scaled by the ferricyanide reductase activities, confirming that all mutants produced functional enzymes.

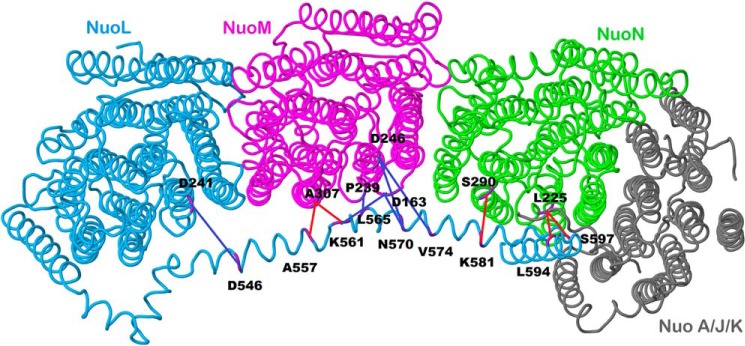

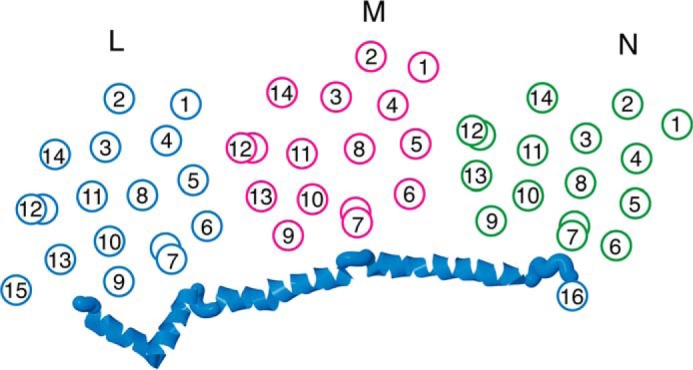

FIGURE 2.

Schematic view of the membrane arm of Complex I showing the sites of cross-links. Subunit L is colored blue, subunit M is magenta, subunit N is green, and subunits A, J, and K are colored gray. Short distance cross-links, which were formed by disulfide bonds, are colored red, whereas longer distance cross-links formed by bifunctional methane thiosulfonates are colored blue. The image was developed from Protein Data Bank code 3rko (16). The view is from the cytoplasm. The peripheral arm would be to the right.

TABLE 1.

Activity measurements of 11 double cysteine mutants that include the L subunit lateral helix

| Mutation | Distancea | Deamino-NADH oxidase activityb | % Deamino-NADH oxidase activityc | Ferricyanide reductase activityb | % Ferricyanide reductase activityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å | nmol/mg protein/min | nmol/mg protein/min | |||

| pBA400 | 165 ± 48 (15)c | 100 | 710 ± 200 (8)c | 100 | |

| A557C(L) + A307C(M) | 4.92 | 137 ± 29 (5) | 83 | 744 ± 45 | 105 |

| K561C(L) + A307C(M) | 4.22 | 133 ± 11 (5) | 81 | 770 ± 55 | 108 |

| L565C(L) + P239C(M) | 5.43 | 160 ± 59 (5) | 97 | 765 ± 15 | 108 |

| K561C(L) + D163C(M) | 12.05 | 270 ± 10 (2) | 164 | 797 ± 12 | 112 |

| N570C(L) + D163C(M) | 13.63 | 161 ± 3 (2) | 98 | 643 ± 22 | 91 |

| N570C(L) + D246C(M) | 10.86 | 250 ± 12 (2) | 151 | 853 ± 15 | 120 |

| V574C(L) + D246C(M) | 16.12 | 230 ± 14 (2) | 139 | 905 ± 13 | 128 |

| K581C(L) + S290C(N) | 6.22 | 138 ± 5 (2) | 84 | 690 ± 43 | 97 |

| L594C(L) + L225C(N) | 4.46 | 86 ± 11 (2) | 52 | 651 ± 21 | 92 |

| S597C(L) + L225C(N) | 5.7 | 161 ± 5 (2) | 98 | 940 ± 43 | 132 |

| D546C(L) + D241C(L) | 13.04 | 230 ± 5 (2) | 139 | 745 ± 62 | 105 |

| BA14 | 18 ± 3 (2) | 11 | 84 ± 2 | 12 |

a Distance between the α-carbons of the native residues.

b Activity was measured in membrane preparations as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The means, S.D., and number of measurements (parentheses) are shown. For ferricyanide reductase activity, two-three measurements were made except for wild type and BA14.

c Activity is expressed as a percentage of the wild type rate.

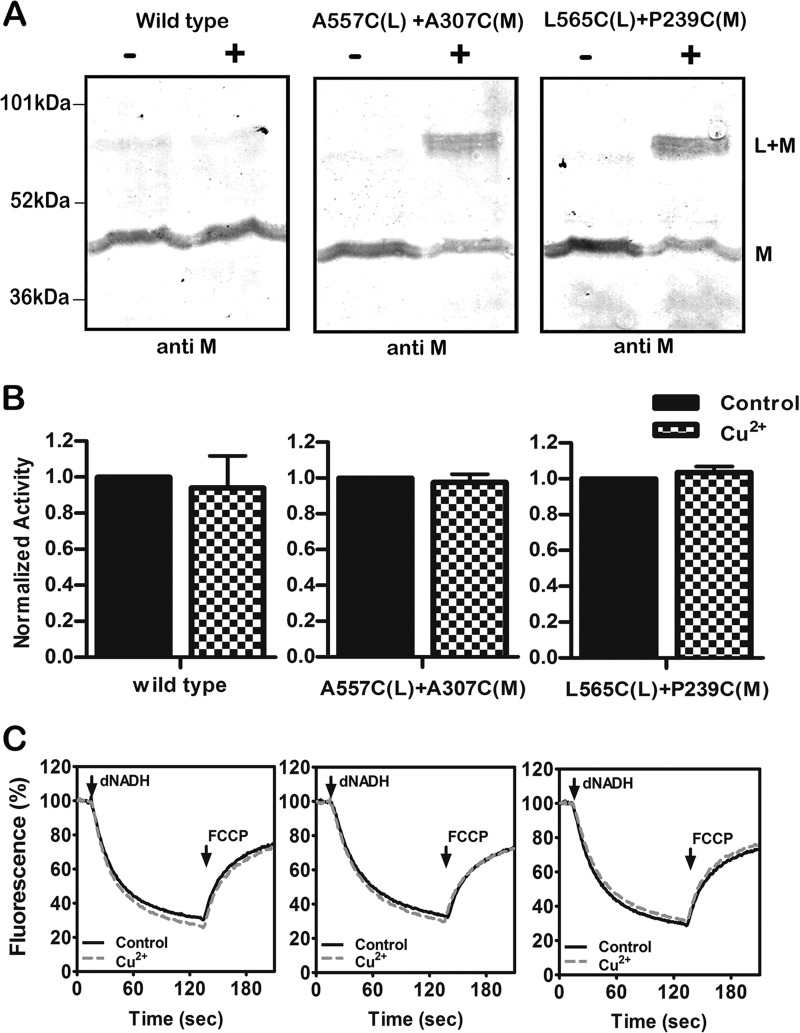

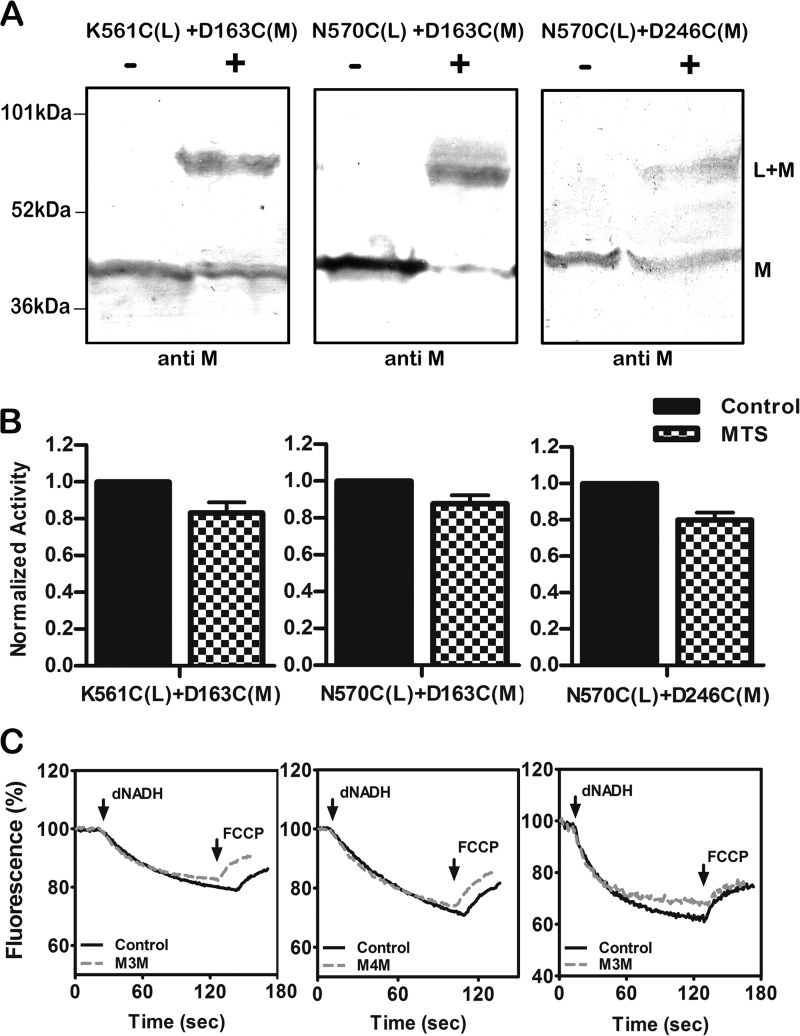

The effects of cross-linking were assessed in three ways. Immunoblots were used to estimate the extent of cross-linked product using antibodies against subunits L or M or against the HA epitope to detect subunit N, which has a C-terminal HA tag. Cross-linking can be seen directly as the appearance of a more slowly migrating band or indirectly as the disappearance of a band for the individual subunit. In some cases the cross-linked product could not be detected directly as one or both of the antibodies did not recognize it. Two different activity assays were carried out. First the NADH oxidase activity was measured before and after the cross-linking reaction. Second, the NADH-driven proton translocation was measured by following the quenching of the fluorescence of an acridine dye, ACMA. Both assays used deamino-NADH. The results for two double mutants are shown in Fig. 3, A557C (nuoL) + A307C (nuoM) and L565C (nuoL) + P239C (nuoM). In panel A it is clear that the CuCl2 treatment (indicated by the +) does not affect the migration of subunit M in the wild type enzyme. For each of the double mutants, a substantial amount of subunit M can be seen to migrate more slowly, consistent with an L-M-cross-linked product. The yield of cross-link was estimated to be ∼75% in each case, as measured by the disappearance of uncross-linked subunit M. Antibody against subunit L did not recognize the cross-linked product. In panel B it is shown that the cross-linking treatment had no effect on the NADH oxidase activity. Likewise, as shown in panel C, there was no effect on proton translocation rates. Three additional pairs of mutations found in the lateral helix in L and in subunit M were analyzed, and the results are shown in Fig. 4. The three mutants are K561C (nuoL) + D163C (nuoM) and N570C (nuoL) + either D163C (nuoM) or D246C (nuoM). These mutants were treated with an MTS reagent, M3M or M4M, as indicated in panel C, to promote cross-linking. In panel A it can be seen that substantial amounts of cross-linking occurred, estimated to be ∼60% (561–163), 90% (570–163), and 50% (570–246). In panel B, a slight decrease I NADH oxidase activity is seen for all three mutants after cross-linking treatment, with 84% activity (561–163), 87% (570–163), and 83% (570–2446). The effects of cross-linking treatment on proton translocation activity are shown in panel C. One cross-linked mutant (570–246) showed a slight decrease, whereas the other two showed no effect at all. One additional cross-link was analyzed, V574C (nuoL) + D246C (nuoM), with similar results (results not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Cross-linking between the HL helix and subunit M using Cu2+ ions. A, representative immunoblots of membrane samples from the wild type strain and from two mutants, A557C (nuoL) + A307C (nuoM) and L565C (nuoL) + P239C (nuoM), are shown with and without treatment with Cu2+ ions to promote disulfide formation. The antibody used was against subunit M. B, the effect of Cu2+ treatment on the deamino-NADH oxidase activity of the wild type strain and the same two mutants is shown. Results are the means and S.E. of at least four measurements from at least two membrane preparations. C, proton translocation assays of the wild type and the same two mutants with and without treatment with Cu2+ ions. The fluorescence quenching of ACMA was initiated by deamino-NADH and was reversed by the addition of FCCP.

FIGURE 4.

Cross-linking between the HL helix and subunit M using MTS reagents. A, representative immunoblots of membrane samples from K561C (nuoL) + D163C (nuoM) and N570C (nuoL) + either D163C (nuoM) or D246C (nuoM) are shown with and without treatment with an MTS reagent to promote cross-link formation. The antibody used was against subunit M. B, the effect of MTS treatment on the deamino-NADH oxidase activity of the three mutants is shown. Results are the means and S.E. of at least four measurements from at least two membrane preparations. C, proton translocation assays of the three mutants with and without treatment with an MTS reagent. The fluorescence quenching of ACMA was initiated by deamino-NADH and was reversed by the addition of FCCP.

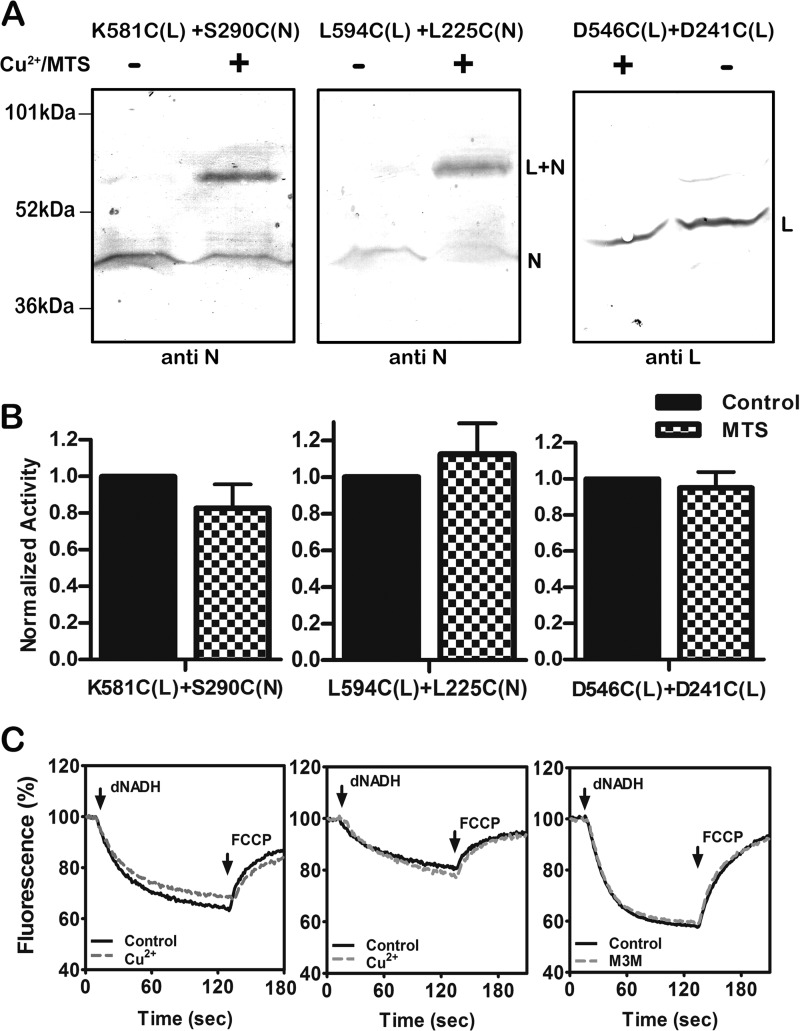

Cross-linking between the lateral helix and residues in nuoN and in other regions of nuoL were also tested. In Fig. 5 the results of the following three double mutants are shown: K581C (nuoL) + S290C (nuoN), L594C (nuoL) + L225C (nuoN), and D546C (nuoL) + D241C (nuoL). The first two double mutants, those between nuoL and nuoN, were cross-linked by treatment with CuCl2, and the results are shown in panel A. The yields of cross-linking were estimated to be ∼50% in each case. In panel B, the effect of cross-linking treatment on NADH oxidase activity is shown. Only small effects were seen: 86% of the untreated sample (581–290) or 110% (594–225). Similarly, only small changes were seen in the proton translocation measurements as shown in panel C.

FIGURE 5.

Cross-linking between the HL helix and subunits N and L. A, representative immunoblots of membrane samples from K581C (nuoL) + S290C (nuoN) and L594C (nuoL) + L225C (nuoN) are shown with and without treatment to promote cross-link formation. The disulfide cross-links between HL and N were catalyzed by Cu2+ ions. The antibody used was against subunit N. B, representative immunoblot of membrane samples from D546C (nuoL) + D241C (nuoL) is shown with and without treatment to promote cross-link formation. The disulfide cross-link within subunit L was generated by M3M. The antibody against L was used, but as previously noted it did not recognize any cross-linked products. C, the effect of Cu2+ ion or MTS reagent (M3M) treatment on the deamino-NADH oxidase activity of the three mutants is shown. Results are the means and S.E. of at least four measurements from at least two membrane preparations. C, proton translocation assays of the three mutants with and without treatment with Cu2+ ions or M3M are shown. The fluorescence quenching of ACMA was initiated by deamino-NADH and was reversed by the addition of FCCP.

In the case of D546C (nuoL) + D241C (nuoL), cross-linking was attempted between the lateral helix and a different region of nuoL using the MTS reagent M3M. In the immunoblot shown in panel A, the probe was the antibody to nuoL, but it did not recognize the cross-linked product. It shows that the band for the individual subunit L was diminished, and so cross-linking can be inferred with an estimated yield of ∼25%. In panel B, the loss of NADH oxidase activity upon cross-linking treatment was <10%, and the proton translocation rate was unchanged, as seen in panel C.

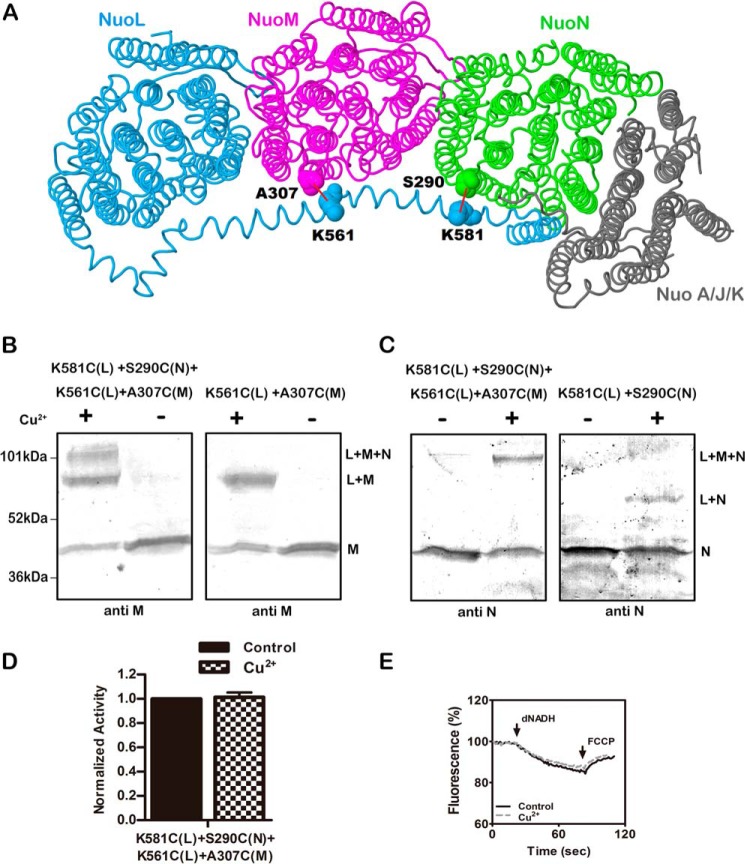

Construction of a Double Cross-link

Because the previously analyzed double cysteine mutants showed little loss of activity upon cross-linking, we attempted to construct a double-cross-linked product to see if more significant loss of activity would be achieved. The new construct included K581C (nuoL) + S290C (nuoN), which was analyzed in Fig. 5, and K561C (nuoL) + A307C (nuoM). This would allow the lateral helix to be cross-linked simultaneously to both subunits M and N, as depicted in panel A of Fig. 6. The disulfide cross-linking was catalyzed by treatment with CuCl2, and the resulting immunoblots are shown in panels B and C. In panel B the blots are probed with anti-M antibody. At the left, three bands can be seen, consistent with the isolated M subunit, an L + M product, and an L + M + N product. The size of the L + M product is confirmed in the blot at the right, which is from the single-pair mutant K561C (nuoL) + A307C (nuoM). In panel C, the blots are probed with anti-HA antibody, which detects nuoN tagged with the HA epitope. In the blot at the left, the double-cross-linked product is confirmed as containing nuoN, whereas the L + N product is only seen in the blot at the right in the simple construct K581C (nuoL) + S290C (nuoN). In panel D it can be seen that the CuCl2 treatment has essentially no effect on the NADH oxidase activity, and very little effect on the proton translocation rate (panel E).

FIGURE 6.

Double cross-linking between the HL helix and both subunits M and N. A, schematic view of the membrane arm of Complex I showing the sites of the two cross-links. Subunit L is colored blue, subunit M is magenta, subunit N is green, and subunits A, J, and K are colored gray. Lys-561 and Lys-581 are in the HL of subunit L. Ala-307 is in subunit M, and Ser-290 is in subunit N. Both of these residues are from the cytoplasmic end of TM9 near the short loop that connects to TM10. The image was developed from Protein Data Bank code 3rko (16). B and C, representative immunoblots of membrane samples from K561C (nuoL) + K581C (nuoL) + A307C (nuoM) + S290C (nuoN) are shown with and without treatment Cu2+ ions to promote cross-link formation. At the left (B), the results are compared with the double mutant K561C (nuoL) + A307C (nuoM). Both blots were probed with antibody to subunit M. At the right (C), the results are compared with the double mutant K581C (nuoL) + S290C (nuoN). Both blots were probed with antibody to subunit N. D, the effect of Cu2+ ion treatment on the deamino-NADH oxidase activity of the quadruple mutant is shown. Results are the means and S.E. of at least four measurements from at least two membrane preparations. E, proton translocation assays of the quadruple mutant with and without treatment with Cu2+ ions are shown. The fluorescence quenching of ACMA was initiated by deamino-NADH and was reversed by the addition of FCCP.

Cross-linking of Subunits at the Cytoplasmic Surface

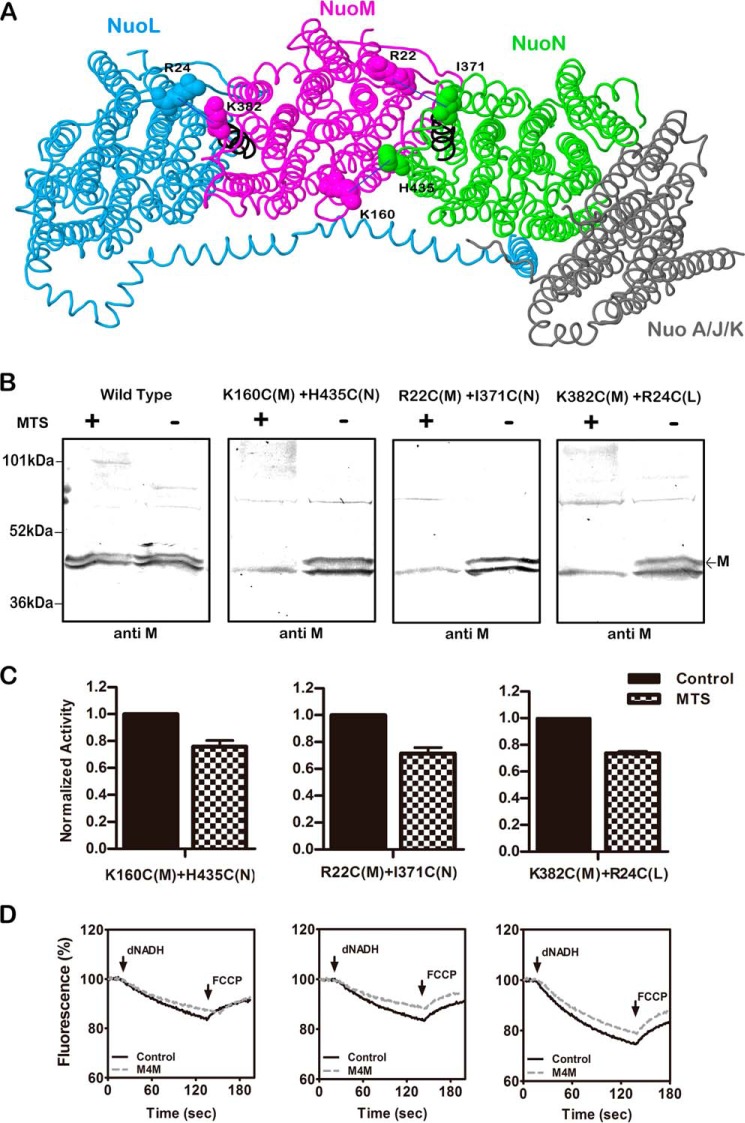

There is a common interface between subunits L and M and between M and N that includes TM1, -4, -5, and -6 of L and M and TM12, -13, and -14 of M and N. The possible dynamics of these interfaces were probed by construction of cysteine residues that were cross-linked by the MTS reagent M4M. Specifically, K160C (M) at the cytoplasmic surface of TM4 was constructed with H435C (N) at the cytoplasmic surface of TM13, R22C (M) at the cytoplasmic surface of TM1 was constructed with I371C (N) at the cytoplasmic surface of TM12a, and R24C (L) at the cytoplasmic surface of TM1 was constructed with K382C (M) at the cytoplasmic surface of TM12a. TM12a is the N-terminal end of the broken helix, found in each of L, M, and N. The locations of the cysteine mutations are shown in Fig. 7, panel A. The mutations were constructed in two different host plasmids, which had somewhat different wild type NADH oxidase activities, presumably due to expression levels. These activities are reported in Table 2. When compared with the appropriate wild type, the 160–435 and 22–371 double mutants had ∼80% of wild type activity, whereas the 382–24 mutant had essentially the wild type level. In the immunoblots shown in Fig. 7, panel B, the anti-M antibody was used to detect cross-links, but no products showed directly. In the wild type, no change in the band for M was seen upon cross-linking treatment, but in the other three constructs, the band disappeared completely, suggesting a high yield cross-link. When assayed for NADH oxidase activity, after cross-linking treatment, each of the double mutants lost 25–30% of the activity, as shown in panel C. The effects of cross-linking treatment upon proton translocation activity, shown in panel D, are consistent with the observed reduction in NADH oxidase activity.

FIGURE 7.

Cross-linking between the L, M, and N subunits at the cytoplasmic surface. A, schematic view of the membrane arm of Complex I showing the sites of the cross-links. Subunit L is colored blue, subunit M is magenta, subunit N is green, and subunits A, J, and K are gray. Arg-24 (TM1) is from subunit L, Arg-22 (TM1), Lys-160 (TM4), and Lys-382 (TM12a) are in subunit M, and Ile-371 (TM12a) and His-435 (TM13) are in subunit N. The image was developed from Protein Data Bank code 3rko (16). B, representative immunoblots of membrane samples from K160C (nuoM) + H435C (nuoN), R22C (nuoM) + I371C (nuoN), and R24C (nuoL) + K382C (nuoM) are shown with and without treatment with the MTS reagent M4M to form cross-links. All blots are probed with antibody to subunit M, which does not appear to recognize the cross-linked products. The marked band corresponds to subunit M, whereas the second band is an artifact. C, the effect of treatment with M4M on the deamino-NADH oxidase activity of the mutants is shown. Results are the means and S.E. of at least four measurements from at least two membrane preparations. D, proton translocation assays of the mutants with and without treatment with M4M are shown. The fluorescence quenching of ACMA was initiated by deamino-NADH and was reversed by the addition of FCCP.

TABLE 2.

Activity measurements of the three double cysteine mutants that occur at the cytoplasmic surface

| Mutation | Distancea | Deamino-NADH oxidase activityb | % Deamino-NADH oxidase activityc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Å | nmol/mg protein/min | nmol/mg protein/min | |

| pBA400-SpeI | 95 ± 8 (5) | 100 | |

| K160C(M) + H435C(N) (pBA400-SpeI) | 14.14 | 77 ± 3 (2) | 81 |

| R22C(M) + I371C(N) (pBA400-SpeI) | 15.58 | 79 ± 6 (2) | 83 |

| pBA400 | 165 ± 48 (15) | 100 | |

| K382C(M) + R24C(L) (pBA400) | 11.8 | 160 ± 12 (2) | 97 |

a Distance between the α-carbons of the native residues.

b Activity was measured in membrane preparations as described in “Experimental Procedures.” The means, S.D., and number of measurements (parentheses) are shown.

c Activity is expressed as a percentage of the wild type rate.

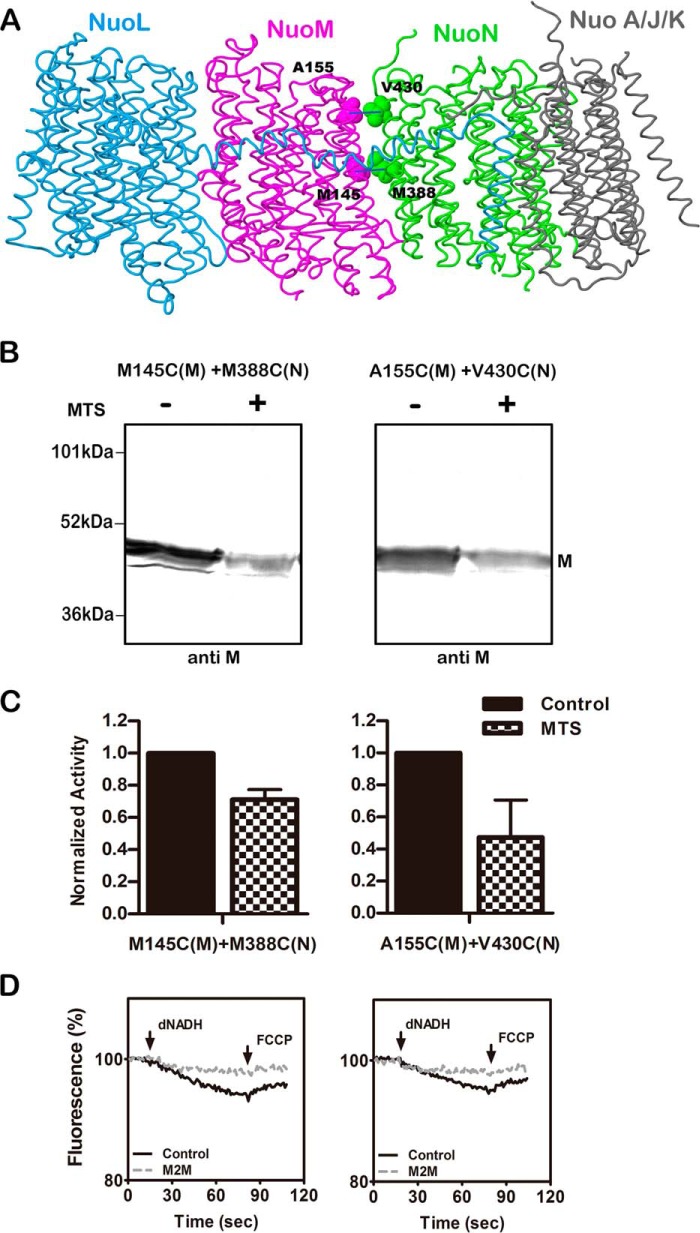

Cross-links between M and N within the Membrane Bilayer

Subunit M has a key glutamic acid residue, Glu-144, embedded in the membrane at TM5, which is near the subunit interface with subunit N. A similar situation exists in subunit L with Glu-144 and its interface with subunit M. Two additional sites of cysteine cross-linking were constructed: M145C (M) + M388C (N) and A155C (M) + V430C (N). The locations of these residues are shown in Fig. 8A. The NADH oxidase activities of these double mutants are shown in Table 3. Unlike the other mutants constructed in this project, these both had <50% of the wild type rate. In the immunoblots shown in Fig. 8B, substantial cross-linking was achieved using the MTS reagent M2M, as indicated by the disappearance of the band for subunit M. It appeared that the anti-M antibody was unable to recognize the cross-linked product. After treatment with M2M the activity of 145–388 dropped by ∼30% and that of 155–430 dropped by ∼50%, as shown in panel C. This probably overstates the residual activity as it is near the background level for this strain. When proton translocation was tested, in both cases the loss of activity was nearly total, as seen in panel D.

FIGURE 8.

Cross-linking between the M and N subunits within the membrane. A, side view of the membrane arm of Complex I showing the sites of the two cross-links within the membrane. Subunit L is colored blue, subunit M is magenta, subunit N is green, and subunits A, J, and K are colored gray. Met-145 and Ala-155 (both TM5) are from subunit M, and Met-388 (TM12b) and Val-430 (TM13) are in subunit N. The image was developed from Protein Data Bank code 3rko (16). B, representative immunoblots of membrane samples from M145C (nuoM) + M388C (nuoN) and A155C (nuoM) + V430C (nuoN) are shown with and without treatment with the MTS reagent M2M to form cross-links. All blots are probed with antibody to subunit M, which does not appear to recognize the cross-linked products. C, the effect of treatment with M2M on the deamino-NADH oxidase activity of the mutants is shown. Results are the means and S.E. of at least four measurements from at least two membrane preparations. D, proton translocation assays of the mutants with and without treatment with M2M are shown. The fluorescence quenching of ACMA was initiated by deamino-NADH and was reversed by the addition of FCCP.

TABLE 3.

Activity measurements of two double cysteine mutations that occur within the membrane bilayer

| Mutation | Distancea | Deamino-NADH oxidase activityb | % Deamino-NADH oxidase activityc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Å | nmol/mg protein/min | nmol/mg protein/min | |

| pBA400-SpeI | 65 ± 1 (2) | 100 | |

| M145C(M) + M388C(N) | 6.31 | 23 ± 1 (2) | 35 |

| A155C(M) + V430C(N) | 5.75 | 31 ± 10 (2) | 48 |

a Distance between the α-carbons of the native residues.

b Activity was measured in membrane preparations as described in “Experimental Procedures.” The means, S.D., and number of measurements (parentheses) are shown.

c Activity is expressed as a percentage of the wild type rate.

Discussion

The unusual lateral helix, HL, between TM15 and TM16 of subunit L was first revealed by the crystallographic analysis of Efremov et al. in 2010 (12). Along with the two conserved broken helices in each of the L, M, and N subunits, it is the most striking structural feature of the membrane arm of Complex I. The authors proposed that the lateral helix might transmit conformational changes in a piston-like fashion, as the site of quinone reduction is rather distant from the L, M, and N subunits, which had been implicated as sites of proton translocation. In fact, the lateral helix makes similar contacts with a broken helix (TM7b) in all three subunits and with the highly conserved cytoplasmic ends of TM9 and TM10 as shown in Fig. 9. For example, residues Ser-290 and Gln-291, which make up the short connection between TM9 and TM10 in subunit N, have an interaction surface with residues Arg-577, Lys-581, and Leu-584 of the lateral helix in subunit L of >100 Å2. Several additional points of contact with each subunit are to the cytoplasmic ends of TM6 and TM13. A potential weakness of the piston model was that the end of the lateral helix and TM16 of subunit L both interact primarily with subunits N and K and are quite remote from the quinone site. Therefore, other elements would be necessary to establish full communication. On the periplasmic side of the membrane, the L, M, and N subunits interact by β-hairpins that extend from L to M and from M to N (16). These β-hairpins each contact the broken helix TM12b, among several other regions. Finally, the L, M, and N subunits also form contacts along the central axis of the membrane region. In particular, there are conserved contacts between TM5, which contains a conserved Glu, and a broken helix TM12 in the adjacent subunit.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic view of the transmembrane helices of subunits L, M, and N of Complex I. Subunit L is colored blue, subunit M is magenta, and subunit N is green. The broken helices TM7 and TM12 are indicated by two offset circles. The HL helix of subunit L is shown as an α-helical ribbon. The contacts between the HL helix and the broken helices, TM7b, of each subunit are shown. The contacts between the broken helices, TM12b, and TM5 of an adjacent subunit are also shown.

Several previous papers (37–40) have analyzed the role of the lateral helix through mutagenesis, including amino acid substitutions, insertions, deletions, and truncations of the C-terminal region of subunit L. C-terminal truncations of TM16 and of most of the lateral helix expressed from the chromosome were found by two groups to result in a nearly total loss of activity (37, 38). Attempts to purify the truncated enzyme were unsuccessful, as it appeared to be unstable. In one case it was shown by immunoblots and activity measurements in native gels of solubilized membranes that Complex I did not assemble (37). These studies confirmed that the C-terminal TM16 of subunit L is structurally important but could not determine whether the lateral helix had a functional role. In a third study (39), an overexpression system was used for purification of Complex I. They showed that a genetic deletion of the entire nuoL did not prevent purification of Complex I lacking L, but the level of subunits M and N appeared low. This approach was used to analyze truncations of subunit L at Trp-592, removing TM16, and at Tyr-544 to additionally remove most of the lateral helix. The results were difficult to interpret in terms of the role of the lateral helix, as the two C-terminal truncations compromised proton translocation to a greater extent than did the complete deletion of subunit L. In the study of Belevich et al. (38) amino acid substitutions at several sites along the lateral helix had no significant effect on activity. Insertions of 6 or 7 residues in the lateral helix generally had no effect or reduced the stability of the complex. Therefore, it appeared that softening the lateral helix did not compromise function unless it also affected stability of the complex. In contrast, Steimle et al. (40) identified one amino acid in the lateral helix, Asp-563, for which substitutions resulted in a partial loss of proton translocation activity. Asp-563 contacts the broken helix TM7b in subunit M. The analogous residue that contacts TM7b in subunit L is Asp-542, but substitutions at that residue had no effect on function. There is also an analogous residue that contacts TM7b in subunit N, Glu-587, but that residue has not yet been mutagenized. In summary of the prior work described, it is clear that the C-terminal region of subunit L, including the lateral helix, is an important structural element of Complex I, but the piston-like mechanism was not tested directly.

In this study the lateral helix of subunit L was constrained by cross-links at 11 different positions and in addition by a double cross-link. In no case was a significant loss of proton translocation activity seen. The results indicate that there are not major movements of the lateral helix relative to the sites of contact. That includes the broken helix of each subunit, TM7b, and for subunits M and N, the highly conserved region at the cytoplasmic ends of TM9 and TM10. In the double cross-linked product, the lateral helix was linked to the TM9–10 region in both subunits M and N without loss of activity. It remains possible that the lateral helix of L moves in concert with the entire contact region in each subunit. If so, that would make it unlikely that it specifically alters the conformation of the broken helix, TM7b. Alternatively, it remains possible that the lateral helix makes important motions but of such a magnitude that they are not constrained by the cross-linking generated in our work.

A different view of the role of the lateral helix is that it serves to maintain the active conformation of the broken helix TM7b in each of the L, M, and N subunits in addition to stabilizing the complex overall. In previous work in this laboratory (23), mutagenesis of residues that are in contact with the lateral helix, such as Tyr-300 (TM10), Lys-158 (TM6), and His-224 (TM7b), all in subunit N, showed partial loss of activity. Similar effects were seen with corresponding mutations in subunits L and M (22). Therefore, disrupting interactions with the broken helix TM7b can affect the activity of the enzyme. The β-hairpins that have been recognized on the periplasmic side of the enzyme (16), connecting L to M and M to N, and also interact with the other broken helix TM12b. They may play a role similar to the lateral helix, not only to stabilize the complex through subunit interactions but also to stabilize the conformation of a broken helix.

Other contact regions between the L, M, and N subunits were probed by five additional cross-links. The cross-links generated between the TM1–2 loop of L or M and TM12, the broken helix of subunits M or N, respectively, had little effect on activity. However, a different picture emerged when the cross-links involved TM5 of subunit M. TM5 of all three subunits contains a highly conserved glutamic acid that is in contact with broken helix TM12 of the adjacent subunit or with subunit K in the case of N. For example, Glu-144 of subunit M in TM5 is in proximity to Lys-395 of subunit N in TM12. The loss of activity upon cross-linking K160C of TM5 in subunit M to H435C of TM13 in subunit N was only ∼25%, but the effects were much greater when the cross-links occurred closer to Glu-144. When M145C in TM5 of subunit M was cross-linked to M388C in broken helix TM12 of subunit N, the loss of activity was nearly complete, as indicated by the proton translocation rate. In this case, because Met-145 is adjacent to key residue Glu-144, it could be seen as a direct effect on the glutamic acid and not necessarily a consequence of constraint by the cross-link. However, the same effect was seen with a cross-link between A155C, 10 residues away in TM5 of subunit M, and V430C in TM13 of subunit N. The results suggest that TM5 is a mobile helix. This is consistent with its location at the junction of two subunits and in proximity to both broken helices: TM12 of the preceding subunit and TM7 of its own subunit. One caveat is that the activity of these mutants is low even before cross-linking, and so more work will be required to establish that mobility of TM5 is important for function.

In summary, the analysis of cross-links between the lateral helix of subunit L and interacting regions of subunits M and N provides no support for a piston-like role of this unusual structural element. Furthermore, the results make it unlikely that the broken helix TM7b must rotate to any significant degree during function. We suggest two possible roles for the lateral helix: to stabilize the membrane subunits in Complex I and to stabilize an active conformation of the broken helix TM7b. Furthermore, from a more limited set of data, it is proposed that TM5, with its conserved glutamic acid, is a more mobile helix that is fundamental in transmitting the conformational changes from subunit N to M and to L.

Author Contributions

S. Z. and S. B. V. designed and analyzed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S. Z. performed the experiments. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica DeLeon Rangel and April Wiseman for technical assistance and Ablat Tursun for assistance in constructing the SpeI plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R15GM099014. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- TM

- transmembrane

- ACMA

- 9-amino 3-chloro 2-methoxy acridine

- BA14

- nuoA-N deletion strain in E. coli

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

- HL

- the lateral helix of subunit L

- MTS

- methane thiosulfonate

- M2M

- 1,2-ethanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate

- M3M

- 1,3-propanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate

- M4M

- 1,4-butanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate

- pBA400

- expression vector for Complex I

- TM7b

- transmembrane helix 7, second segment.

References

- 1. Balsa E., Marco R., Perales-Clemente E., Szklarczyk R., Calvo E., Landázuri M. O., Enríquez J. A. (2012) NDUFA4 is a subunit of Complex IV of the mammalian electron transport chain. Cell Metab. 16, 378–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carroll J., Fearnley I. M., Skehel J. M., Shannon R. J., Hirst J., Walker J. E. (2006) Bovine Complex I is a complex of 45 different subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32724–32727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hirst J. (2013) Mitochondrial complex I. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 551–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brandt U. (2006) Energy converting NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (Complex I). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 69–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loschen G., Flohé L., Chance B. (1971) Respiratory chain linked H2O2 production in pigeon heart mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 18, 261–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goncalves R. L., Quinlan C. L., Perevoshchikova I. V., Hey-Mogensen M., Brand M. D. (2015) Sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by muscle mitochondria assessed ex vivo under conditions mimicking rest and exercise. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 209–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu H., Cao X. (2008) GRIM-19 is essential for maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1893–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinvalet D., Dykxhoorn D. M., Ferrini R., Lieberman J. (2008) Granzyme A cleaves a mitochondrial complex I protein to initiate caspase-independent cell death. Cell 133, 681–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vinothkumar K. R., Zhu J., Hirst J. (2014) Architecture of mammalian respiratory complex I. Nature 515, 80–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hunte C., Zickermann V., Brandt U. (2010) Functional modules and structural basis of conformational coupling in mitochondrial Complex I. Science 329, 448–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zickermann V., Wirth C., Nasiri H., Siegmund K., Schwalbe H., Hunte C., Brandt U. (2015) Structural biology: mechanistic insight from the crystal structure of mitochondrial complex I. Science 347, 44–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Efremov R. G., Baradaran R., Sazanov L. A. (2010) The architecture of respiratory Complex I. Nature 465, 441–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morgan D. J., Sazanov L. A. (2008) Three-dimensional structure of respiratory complex I from Escherichia coli in ice in the presence of nucleotides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sazanov L. A., Hinchliffe P. (2006) Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory Complex I from Thermus thermophilus. Science 311, 1430–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baradaran R., Berrisford J. M., Minhas G. S., Sazanov L. A. (2013) Crystal structure of the entire respiratory complex I. Nature 494, 443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Efremov R. G., Sazanov L. A. (2011) Structure of the membrane domain of respiratory complex I. Nature 476, 414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guénebaut V., Vincentelli R., Mills D., Weiss H., Leonard K. R. (1997) Three-dimensional structure of NADH dehydrogenase from Neurospora crassa by electron microscopy and conical tilt reconstruction. J. Mol. Biol. 265, 409–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leonard K., Haiker H., Weiss H. (1987) Three-dimensional structure of NADH: ubiquinone reductase (complex I) from Neurospora mitochondria determined by electron microscopy of membrane crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 194, 277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pohl T., Bauer T., Dörner K., Stolpe S., Sell P., Zocher G., Friedrich T. (2007) Iron-sulfur cluster N7 of the NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I) is essential for stability but not involved in electron transfer. Biochemistry 46, 6588–6596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weidner U., Geier S., Ptock A., Friedrich T., Leif H., Weiss H. (1993) The gene locus of the proton-translocating NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase in Escherichia coli: organization of the 14 genes and relationship between the derived proteins and subunits of mitochondrial Complex I. J. Mol. Biol. 233, 109–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaila V. R., Wikström M., Hummer G. (2014) Electrostatics, hydration, and proton transfer dynamics in the membrane domain of respiratory complex I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 6988–6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michel J., DeLeon-Rangel J., Zhu S., Van Ree K., Vik S. B. (2011) Mutagenesis of the L, M, and N subunits of Complex I from Escherichia coli indicates a common role in function. PLoS ONE 6, e17420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amarneh B., Vik S. B. (2003) Mutagenesis of subunit N of the Escherichia coli Complex I: identification of the initiation codon and the sensitivity of mutants to decylubiquinone. Biochemistry 42, 4800–4808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato M., Sinha P. K., Torres-Bacete J., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2013) Energy transducing roles of antiporter-like subunits in Escherichia coli NDH-1 with main focus on subunit NuoN (ND2). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 24705–24716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Torres-Bacete J., Sinha P. K., Sato M., Patki G., Kao M. C., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2012) Roles of subunit NuoK (ND4L) in the energy-transducing mechanism of Escherichia coli NDH-1 (NADH:quinone oxidoreductase). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 42763–42772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Kao M. C., Chen H., Sinha S. C., Yagi T., Ohnishi T. (2010) The membrane subunit NuoL(ND5) is involved in the indirect proton pumping mechanism of E. coli complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39070–39078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Torres-Bacete J., Sinha P. K., Castro-Guerrero N., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2009) Features of subunit NuoM (ND4) in Escherichia coli NDH-1: topology and implication of conserved Glu-144 for coupling site 1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33062–33069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Torres-Bacete J., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2007) Characterization of the nuoM (ND4) subunit in Escherichia coli NDH-1: conserved charged residues essential for energy-coupled activities. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36914–36922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Euro L., Belevich G., Verkhovsky M. I., Wikström M., Verkhovskaya M. (2008) Conserved lysine residues of the membrane subunit NuoM are involved in energy conversion by the proton-pumping NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1166–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ohnishi T. (2010) Structural biology: piston drives a proton pump. Nature 465, 428–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Amarneh B., De Leon-Rangel J., Vik S. B. (2006) Construction of a deletion strain and expression vector for the Escherichia coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 1557–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore K. J., Fillingame R. H. (2008) Structural interactions between transmembrane helices 4 and 5 of subunit a and the subunit c ring of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31726–31735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steed P. R., Fillingame R. H. (2008) Subunit a facilitates aqueous access to a membrane-embedded region of subunit c in Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12365–12372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kao M.-C., Di Bernardo S., Perego M., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2004) Functional roles of four conserved charged residues in the membrane domain subunit nuoa of the proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32360–32366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sobolev V., Sorokine A., Prilusky J., Abola E. E., Edelman M. (1999) Automated analysis of interatomic contacts in proteins. Bioinformatics 15, 327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sobolev V., Eyal E., Gerzon S., Potapov V., Babor M., Prilusky J., Edelman M. (2005) SPACE: a suite of tools for protein structure prediction and analysis based on complementarity and environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W39–W43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Torres-Bacete J., Sinha P. K., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2011) Structural contribution of C-terminal segments of NuoL (ND5) and NuoM (ND4) subunits of complex I from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 34007–34014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Belevich G., Knuuti J., Verkhovsky M. I., Wikström M., Verkhovskaya M. (2011) Probing the mechanistic role of the long α-helix in subunit L of respiratory Complex I from Escherichia coli by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 82, 1086–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steimle S., Bajzath C., Dörner K., Schulte M., Bothe V., Friedrich T. (2011) Role of subunit NuoL for proton translocation by respiratory complex I. Biochemistry 50, 3386–3393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steimle S., Willistein M., Hegger P., Janoschke M., Erhardt H., Friedrich T. (2012) Asp-563 of the horizontal helix of subunit NuoL is involved in proton translocation by the respiratory complex I. FEBS Lett. 586, 699–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]