Abstract

A 57-year-old man was admitted with right arm weakness and numbness on the background of intermittent headaches. On examination he was found to have mildly decreased sensation, power was 4/5 on the right side. He had dyspraxia in the right hand and was unable to spell his name. His speech was hesitant and he had left-sided visual field impairment as well as some photophobia. MRI and CT revealed multiple areas of haemorrhage and infarctions raising the possibility of primary angitis of brain. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. The patient responded to steroids and immunosuppressants partially.

Background

Sudden onset weakness of one arm and leg is most commonly secondary to cerebral thrombosis. Rarely, however, the cause may be primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS). One should consider this diagnosis if the neurological deficit can not be explained easily by the vascular territory of the area of infarct and appears to be multifocal or widespread. CT, MRI, angiogram and biopsy will help in confirming the diagnosis. It is important to make this diagnosis as the treatment is different from that of a typical stroke. Immunosuppression with steroids and other agents can be rewarding.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old male lecturer was admitted with a 2-month history of right arm weakness and numbness. This was on a background of 10 months of left-sided headaches with intermittent episodes of decreased visual field mainly on the left. CT head 6 months before was normal. He had also become uncharacteristically sleepy and on further questioning a slight change in mood and personality had been noted with some deterioration in memory and a change in the sense of smell.

On examination he was found to have mildly decreased sensation, power was 4/5 on the right side. He had dyspraxia in the right hand and was unable to spell his name. His speech was hesitant and he had left visual field impairment as well as some photophobia.

While on the ward he had a number of episodes of severe headache associated with nausea and vomiting which subsided with analgesia.

Investigations

Blood results were all within normal limits, in particular erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 11 mm, antinuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anticardiolipin antibody were negative.

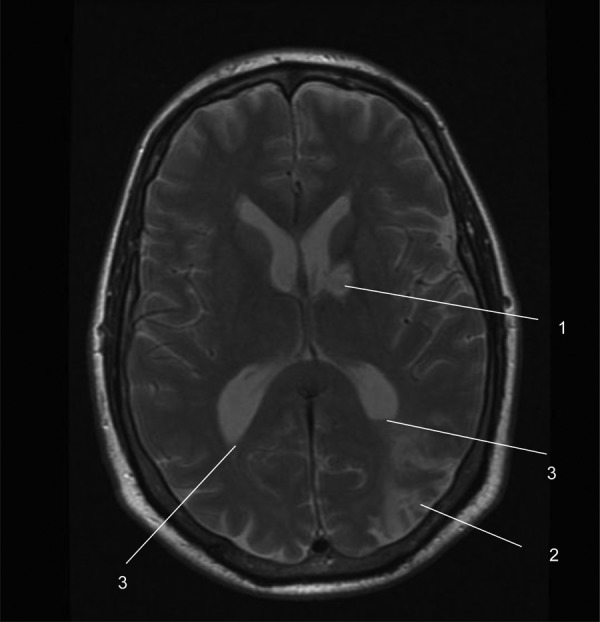

MRI brain (figures 1–3) showed evidence of cortical infarction across more than one vascular territory. Signal change consistent with non-acute blood was present in the ventricles, left internal capsule and possibly within the sulci. The possibility of vasculitis was raised.

Figure 1.

MRI slice from our patient showing a left basal ganglia haemorrhagic infarct (1), a left parieto-occipital infarct (2) and blood in the occipital horns of both lateral ventricles (3).

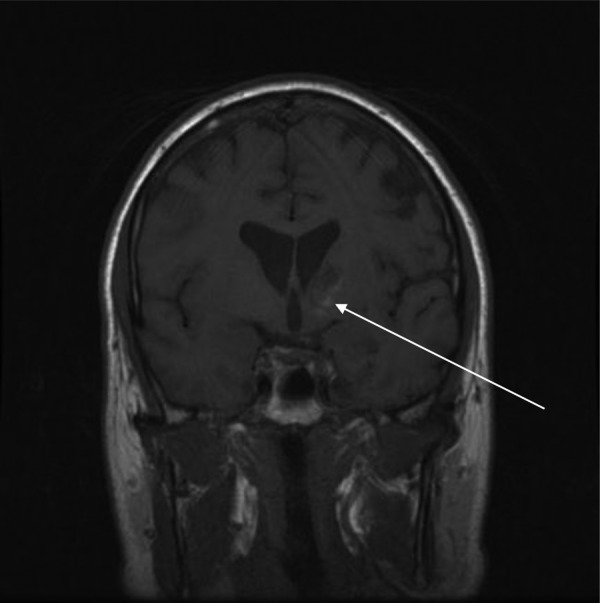

Figure 2.

A coronal MRI slice from our patient showing blood in the left basal ganglia (arrow).

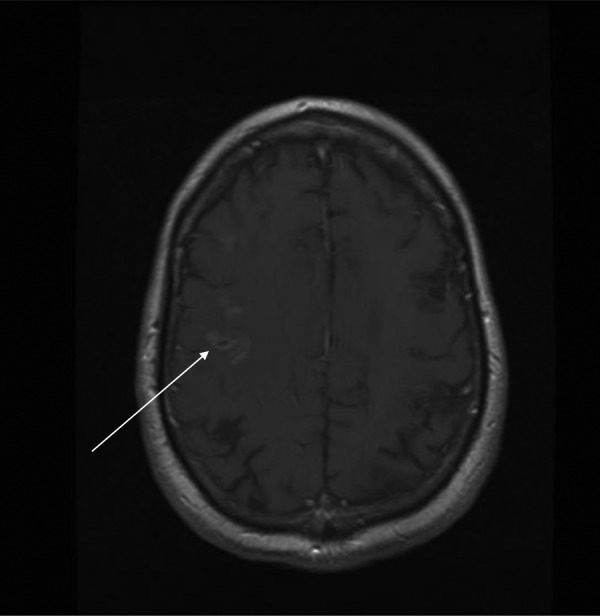

Figure 3.

MRI slice from our patient showing pathological gyral enhancement over the right parietal lobe (arrow).

CT brain showed signal change consistent with subacute blood in the occipital horns of both lateral ventricles. Hypodense areas were noted in the left frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital horns as well as in the right parietal lobe.

There was consensus that there were two infarcts—one in the left internal capsule and one in the left posterior parietal lobe. High signal areas were felt to be secondary to laminar necrosis (infarction which develops secondary to generalised hypoxia rather than local vascular abnormality).

Lumbar puncture revealed an opening pressure of 23 cm H2O. Fluid appeared sanguineous. Protein was 0.70 g/l and fluid was positive for xanthochromia. White cell count 4/mm3. Red blood count >1000/mm3. Gram stain and culture were negative.

Ultrasound carotid Doppler scan and ECHO was normal.

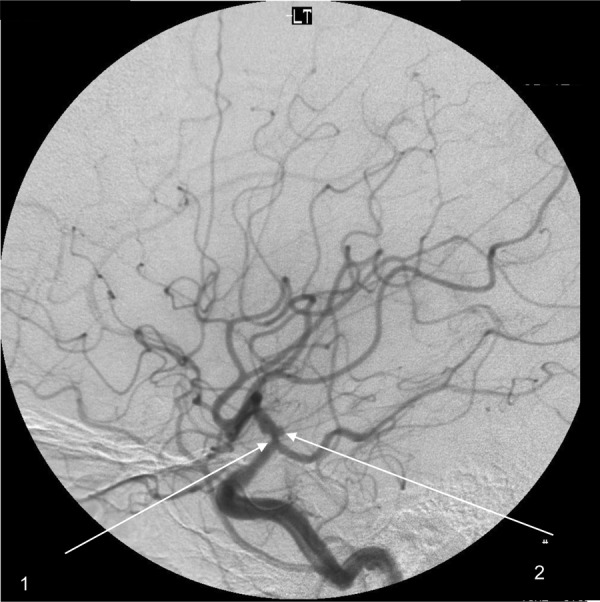

Angiogram (figure 4) showed irregularity in cerebral blood vessels, compatible with vasculitis. It also showed a small left sessile aneurysm.

Figure 4.

Angiogram image from our patient showing irregular narrowing (1) and aneuyrsmal dilatation of the left terminal carotid artery (2).

Brain biopsies performed within 4 weeks of initial presentation, confirmed vasculitic changes.

Differential diagnosis

On admission this included multiple transient ischemic attacks, demyelination, migraine and encephalitis. Recent social stresses were also initially thought to be playing a factor. A vasculitic process, that is, cerebral angiitis was also considered—this was the main differential after the imaging was carried out.

Differential diagnoses for similar presentations is wide-ranging and must be actively ruled out before concluding that PACNS is the cause. These include: aspergillosis; atrial myxoma with embolisation to the brain; Behcet disease, CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy); Churg-Strauss syndrome; eclampsia; fibromuscular dysplasia; giant cell arteritis; Henoch-Schonlein purpura; Herpes simplex encephalitis; histoplasmosis; HIV-1; malignant hypertension; infectious endocarditis with septic embolisation to the brain; intravascular lymphoma; meningovascular syphilis; primary and metastatic CNS neoplasms; migraine headaches; Moyamoya disease; multiple sclerosis; neurosarcoidosis; paraneoplastic PACNS: Hodgkin's disease, polyarteritis nodosa; rheumatoid arthritis; Sjogren syndrome; systemic lupus erythematosus; tuberculosis and Wegener granulomatosis.

Treatment

The patient was not given aspirin as the lumbar puncture confirmed subarachnoid haemorrhage. In light of the findings on MRI and a strong suspicion of vasculitis dexamethasone was started. Later, methylprednisolone was started with Proton Pump Inhibitor cover—initially 1 g intravenous for 3 days, then 60 mg oral with gradual decrease. This brought about improvement of symptoms—upper-limb weakness and confusion improved.

In light of the finding of xanthochromia in the cerebrospinal fluid and aneurysm noted on angiogram the neurosurgical team carried out a left temporal craniotomy to explore the internal carotid artery and exclude the presence of a saccular aneurysm. During surgery a false aneurysm of the left carotid artery which could explain the haemorrhage was found. This was wrapped where it was adjacent to the anterior choroidal artery take-off. Biopsies of the superficial temporal artery, dura and frontal cortex were obtained.

Outcome and follow-up

He was initially treated with steroids with continued improvement in his symptoms. Phenytoin was started in the postoperative period due to the development of seizures.

After brain biopsy, intravenous pulsed cyclophosphamide was started, initially weekly then monthly for 6 months, with gradual reduction in steroid dose. Cyclophosphamide was eventually replaced by azathioprine. Phenytoin later needed increasing because of seizures during sleep.

Follow-up MRI, almost a year after initial hospital admission showed areas of established infarction in the areas of previous ischaemic changes. The multifocal pattern of infarction seen was felt to be consistent with a vasculitic process. No new areas of infarction or bleeding were seen which was felt to confirm that there was no recurrence of his vasculitis.

Discussion

Primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS) is a rare (incidence of 2.4 cases per million patient years) disorder resulting in inflammation and destruction of CNS vessels without evidence of vasculitis outside the CNS.1 It is poorly understood, with non-specific presentations, lack of specific non-invasive diagnostic tests and no randomised trials of treatments.1 Despite this, progress is being made and slowly a clear view of the different clinical and pathological subtypes with prognostic implications is emerging. There is now also a better understanding of the fact that PACNS can be mimicked closely in both clinical presentation and radiological manifestations by a number of disorders, most frequently the group of disorders known collectively as ‘reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes (RCVS).The ability to recognise mimics has also improved.1 2

The criteria for diagnosis are:

The presence of an acquired otherwise unexplained neurological or psychiatric deficit.

The presence of either classic angiographic or histopathological features of angiitis within the CNS.

No evidence of systemic vasculitis or any disorder that could cause or mimic the angiographic or pathological features of the disease.3

As with our patient, all three criteria must be met to make a diagnosis of PACNS.2 Further division into subtypes is described elsewhere.1

Our patient, being 57, falls close to the peak presentation age of 50, though PACNS can affect all ages. It is most common in men. As with our patient, the clinical signs and symptoms are non-specific and reflect the diffuse and often patchy nature of the pathological process. The course of the illness is also variable with presentations ranging from hyperacute to chronic and insidious.1

Although PACNS can present in many ways, this diagnosis should be considered in patients with the following presentations:

Cerebral ischaemia that affects different vascular territories and that is distributed over time, in association with inflammatory changes in the CSF.

Subacute or chronic headache with cognitive impairment or chronic aseptic meningitis.

Chronic meningitis after infectious and neoplastic disorders have been ruled out.1

Our patient presented with a number of non-specific neurological symptoms, including one of the most common symptoms of PACNS—headache, though in different cases this often varies in description, intensity and pattern. Strokes and transient ischaemic attacks are also common. Stroke usually affects many different vessels, as it did in our case—presentation of PACNS as a single stroke is uncommon. Importantly, signs and symptoms of systemic vasculitis are rare, and if present should raise the likelihood of systemic illness.1

In a series of 116 patients with pathologically confirmed disease, nearly 70% of patients presented with diffuse neurological dysfunction which included:

Decreased cognition (83%)

Headache (56%)

Seizure (30%)

Stroke (14%)

Cerebral haemorrhage (12%)4

Symptoms and signs of untreated PACNS progress over the course of months. This is an important contrast to the reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes (a group of disorders linked by prolonged but reversible vasoconstriction of the cerebral arteries) which typically have a more acute onset and much shorter time to diagnosis.4

Accurate and timely diagnosis of PACNS is challenging in the absence of confirmatory serological tests and the limited sensitivity and specificity of CSF examination, cerebral angiography, and brain biopsy. A common pitfall is to start immunosuppressive treatment without establishment of diagnosis or exclusion of mimics which have been mentioned earlier on.1

Several modalities are available to assist in the diagnosis of PACNS. No single lab test has sufficient sensitivity or specificity to provide a high degree of positive or negative predictive value that enables clinicians to establish or rule out the diagnosis without additional diagnostic modalities. Acute phase reactants such as CRP and ESR are usually normal, as was the case with our patient, but help in the assessment of the likelihood of a systemic inflammatory disease. The same can be said for serological tests for autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, as well as molecular testing for infections and blood cultures.1 5

CSF analysis is essential—its central role is to exclude infectious or malignant diseases.1 5 Abnormal findings occur in 80–90% of pathologically documented cases of PACNS.3 5 Typical findings include aseptic meningitis, with modest lymphocytic pleocytosis (median CSF white blood cell count <20 cells/ml), normal glucose, raised protein concentrations (median CSF protein concentrations <120 mg/dl) and occasionally the presence of oligoclonal bands and increased IgG synthesis.6 Generally, the combination of normal findings on MRI and normal CSF analysis has a high negative predictive value for the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis.7

MRI is the main neuroradiological modality for the work-up of patients with suspected PACNS. Sensitivity in these patients is 90–100%.6 Abnormalities include changes in the subcortical white matter, deep grey matter, deep white matter and the cerebral cortex.8 Infarcts are the most common lesions, occurring in up to 53% of patients,9 and were present in our patient. As we saw, multiple infarcts often occur. MRI findings should be interpreted by an expert neuro-radiologist who is familiar with the findings of CNS vasculitis and its radiological mimics.5

When using angiography (direct or indirect) in the diagnostic work-up the typical findings of PACNS include alternating areas of stenosis and dilatation (‘beading’), which can be smooth or irregular and typically occur bilaterally but can also include single vessels.1 Other findings include circumferential or eccentric vessel irregularities and multiple occlusions with sharp cut-offs. These findings however can be false positive or false negative in a large number of cases.

Brain biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis of PACNS—its value is in the positive identification of angiitis in cases where vascular imaging is inconclusive, and also for identification of PACNS mimics that cannot be diagnosed in a less invasive manner. Unfortunately, similar to other tests, it is still limited by low specificity—a non-diagnostic or negative biopsy does not rule out the diagnosis, mainly due to the irregular involvement or inaccessibility of the lesions.1 Histologically, the inflammatory process is lymphocytic with a variable number of plasma cells, histiocytes, and eosinophils. Necrotising vasculitis occurs in 25% of patients.1

When it comes to treating PACNS, unfortunately there have been no randomised studies and all the information on treatment is based on retrospective data and clinical experience. Most case series suggest a good outcome when patients are treated with glucocorticoids or glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide as with our patient.1

Although understanding of PACNS has progressed greatly in recent times, there are still gaps in knowledge about its pathogenesis; there is no efficient non-invasive method for diagnosis, nor any treatment guidelines. Hopefully the establishment of a multicentre registry and the development of randomised trials will help further progress.1

Learning points

Any neurological deficit which cannot be explained by the territorial distribution of cerebral circulation should prompt the diagnosis of multifocal brain disease like vasculitis.

Vasculitis can be localised to one organ, like the brain in this case.

Cerebral vasculitis may not be associated with traditional inflammatory blood markers like high erythrocyte sedimentation rate and autoantibodies.

Cerebral vasculitis can be suspected on brain imaging and confirmed with biopsy.

It is important to make the diagnosis as the treatment is immunosuppression and can be rewarding.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Hajj-Ali R, Singhal A, Benseler S, et al. Primary angiitis of the CNS. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:561–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younger DS. Vasculitis of the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol 2004;17:317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988;67:20–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabrese LH, Duna GF, Lie JT. Vasculitis in the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajj–Ali R, Calabrese LH. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate. Waltham MA: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neel A, Paganoux C. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27(Suppl 52):S95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone JH, Pomper MG, Roubenoff Ret al. Sensitivities of noninvasive tests for central nervous system vasculitis: a comparison of lumbar puncture, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomper MG, Miller TJ, Stone JH, et al. CNS vasculitis in autoimmune disease: MR imaging findings and correlation with angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:75–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neuro 2007;62:442–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]