Abstract

Approximately 30% of the world population presents with tuberculosis. In developed countries, genitourinary manifestation is responsible for over 40% of extrapulmonary cases. Genitourinary tuberculosis is often diagnosed in the later stage due to the fact that the symptoms are non-specific and technical difficulties to isolate the tubercle bacillus through bacilloscopy or culture in specific medium are many. We present a case of a 47-year-old African-American woman with relapsing urinary infection and sterile pyuria. After a 4 four-year evolution, the patient developed functional exclusion of the right kidney as a consequence of chronic pyelonephritis. The investigation result for alcohol-acid bacillus resistant in urine was positive along with the culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Background

Tuberculosis is a disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its most common clinical manifestation is pulmonary. Among the extrapulmonary cases, lymphatic tuberculosis is the most frequent, followed by genitourinary tuberculosis, which represents 30% of the extrapulmonary cases worldwide1 2 and reaches rates of 40–60% in developed countries.3

Tubercle bacillus infection is almost always airborne and it is followed by replication of the bacillus in alveolar macrophages which form the characteristic Ghon nodule. The mycobacteria remain latent until active form of the disease develops and possibly spreads to extrapulmonary organs haematogenically or, differently from other urinary bacterial infections, via a descending pathway. The bacilli then spread to the renal tubules, and once they involve the calyces they cause necrosis and papillary abscess which grows and forms cavitations in the renal capsule.3 4

The characteristic symptoms are suprapubic or flank pain, nocturia and haematuria, with possible irritating urinary symptoms, especially when there is no response to antibiotic therapy, like polyuria and urination difficulty. Such aspects lead to further investigation of the disease.3 4 Besides, the presence of sterile pyuria strongly suggests that genitourinary tuberculosis should be investigated.1–4

Secondary bacterial infections may occur in up to 50% of the cases3 and immunodepressive patients, like HIV carriers, are at higher risk.1 The evolution to a total loss of renal function and the beginning of substitution therapy are not frequent. However, cases of tubulointerstitial nephritis and granuloma have increasingly been described in the literature.5–7

Case presentation

A 47-year-old African-American woman presented relapsing cases of infection of the urinary tract, not investigated, for 4 years. After using various types of antimicrobials, she was evaluated by a nephrologist. There was no family history of renal disease and she had no history or alterations in the gynaecological tract. Decreased urinary output, mild or moderate and urinary tract infections in childhood were not reported. The patient was a non-smoker and had no past record of pulmonary diseases. Vaccines were updated.

Abdominal exams showed no alterations and lymphnodes research was negative. At presentation her blood pressure was 124/70 mm Hg and her heart rate was 84 bpm. Gynaecological examinations were unaltered. Blood and urine exams, the latter with culture, were requested. The absence of bacterial growth along with leucocyturia led to the investigation for the acid–alcohol resistant bacillus. Five urine samples were collected and they all had a positive result, later confirmed by the specific urine culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis once the bacilloscopy was also positive in the presence of other mycobacteria. Table 1 shows the other laboratorial alterations at first presentation.

Table 1.

Laboratorial data

| Variable | Reference range | On presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 12–16 | 12.5 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 36–46 | 39.5 |

| White blood count (mm³) | 6300 | 8300 |

| Platelets (mm³) | 388000 | 393000 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.5–1.3 | 1.1 |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 15–50 | 35 |

| Potassium (mEq/l) | 3.5–5.1 | 4 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | < 0.3 | 14.99 |

| Urinalysis | ||

| pH | 6.0 | |

| Density | 1005–1035 | 1024 |

| Protein (g/dl) | Neg | 0.01 |

| Leucocytes (ml) | 10000 | 1000000 |

| Red cells (ml) | 8000 | 32000 |

| Crystals | Neg | Neg |

| Casts | Neg | Neg |

| Urine culture | Neg | Neg |

| Acid fast bacilli | Neg | + |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture | Neg | + |

| HIV | Neg | Neg |

CRP, C reactive protein; Neg, negative.

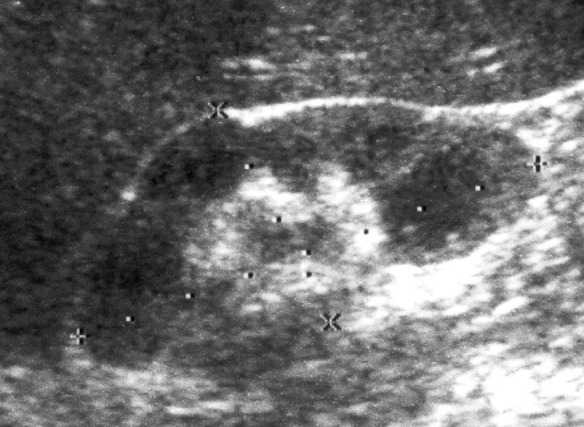

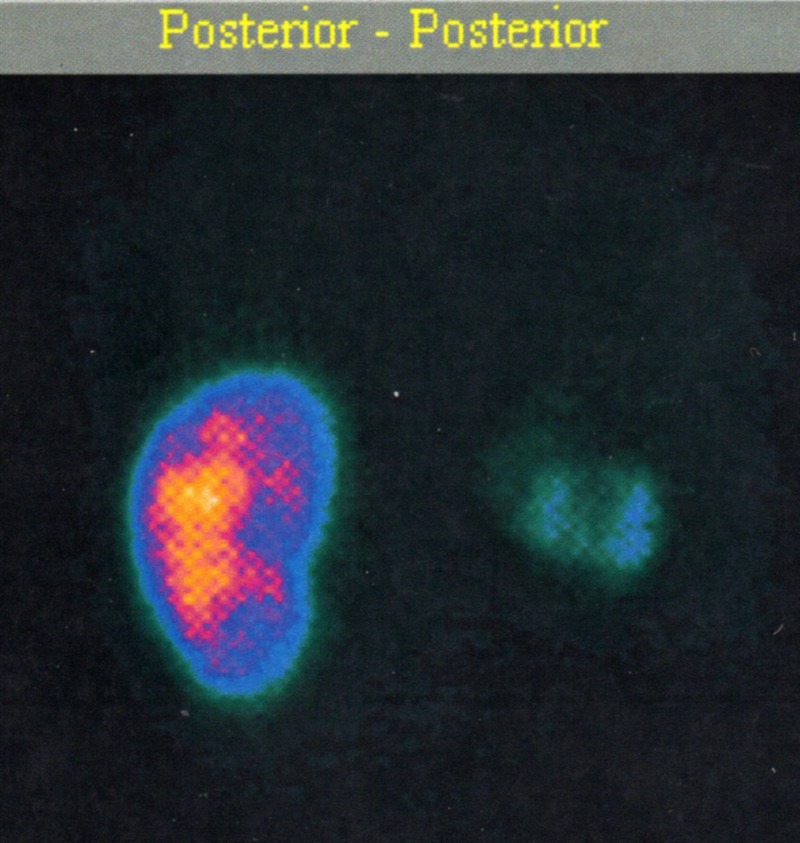

Diagnostic image investigation started with a thorax x-ray and no alterations were found. The renal ultrasound revealed a reduction in length and echotexture of the right kidney—8.5 cm in its longest axis—whereas the left kidney measured 10.4 cm. Right pyelic and ureteral dilatations were also observed with no signs of renal calculus (figure 1). With the abdominal CT scan the presence of obstructive factors was eliminated and right hydroureteronephrosis with renal cortical thinning was confirmed. There were no alterations in retrograde and mictional urethrocystography. Scintigraphy with Tc 99m-dimercaptosuccinic acid renal image showed evidence of an acute reduction in size of the right kidney with hypocaptation in relation to the contralateral kidney and relative tubular function of 14% (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Right kidney ureteric and pielic dilation.

Figure 2.

Right kidney DMSA-Tc 99m reduced capitation.

The patient underwent an antitubercular treatment with rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Alterations in hepatic or renal functions were not observed. Owing to functional exclusion of the infected kidney along with tuberculosis, nephrectomy was indicated.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of this case involves investigation for the most common pathogens responsible for urinary infections. Over 95% of the infection cases are caused by enterobacteria. Chlamydia trachomatis is another important pathogen to be considered as a cause of acute urethral syndromes. In the event of concomitant corticosteroids use, diabetes or the presence of a vesical probe, Candida sp should be investigated.3 4

It is important to point out that the presence of resistant alcohol–acid bacilli in urinalysis only shows the existence of mycobacteria in the sample, and thus the culture of the pathogenic agent is always important for accurate diagnosis.8 Association of pulmonary or lymphatic diseases , along with the immunological profile of the patient, complement disease diagnostic investigation.

Outcome and follow-up

Once the patient started treatment for tuberculosis, there was improvement in her symptoms. She underwent right unilateral nephrectomy 4 months after beginning of the treatment.Two months after surgery there were no traces of bacillus in her urine. Histological analysis revealed chronic pyelonephritis with glomerulosclerosis, foci of abscesses and widespread fibrinoid necrosis. A chronic inflammatory process was observed in the right ureter associated with dilated lumen and absence of M tuberculosis under investigation, after 4 months of treatment. Renal function remained stable throughout this period. After nephrectomy, the patient made use of ciprofloxacin for 10 days. No other urinary tract infection episodes were reported.

Discussion

The present case shows with authority the difficulty in recognising extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases in immunocompetent patients. In the event of relapsing or persistent infections, constant changes in antibiotic therapy are frequent in clinical practise.3 The great number of secondary bacterial infections in the presence of M tuberculosis encourage this practise.1 4

The most common symptoms mimic those of low urinary tract infection. The first suspicions seem to arise only when conventional antimicrobial therapy is not effective or when there is presence of sterile leucocyturia3 a fact that often results in late disease diagnosis.

The cytological analysis of urine in specific colouration is sensitive for detection of mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium bovis or Mycobacterium avium, but very little specifically for M tuberculosis.8 A positive result may be confirmed through specific culture for M tuberculosis or through polymerase chain reaction (sensibility=94.7%).3 4 7 8

The structural alterations of the urinary tract caused by renal tuberculosis depend on where the infection first occurred. Histologically, tubulointersticial nephritis with chronic evolution occurs in the kidney along with caseous granuloma formations. The sooner the disease is diagnosed and treatment started, better are the chances to revert the patient's condition.1 The ureter and the bladder are usually affected through the collector system. Ureteral constriction often occurs, a fact that may lead to stenosis and subsequent kidney removal. The urinary bladder could be affected by the formation of an acute inflammatory process, ulceration and vesicular formations in its wall, culminating in fibrosis, with possible extension to the urethral meatus.4 7 8

The radiological alterations observed in renal ultrasound may be classified under six different types of presentation: nephrectasia (type I), hydrops (type II), empyema (type III), calcification (type IV), inflammatory and atrophic (type V) and mixed (type VI).9

Calcifications are common and easily identified in a simple abdominal x-ray. The helicoidal abdominal CT scan is of great importance to observe the evolution and calcification of renal parenchyma and the adjacent structures. It has been used to describe all the characteristic lesions found.7 9

Although uncommon, evolution to terminal renal disease and dialysis may occur. The mechanism of evolution to terminal renal disease is the same and it encompasses parenchymal infection and urinary tract obstruction which develops into chronic obstructive uropathy.9 An old series of 102 cases has already shown the importance of early diagnosis and proper treatment of renal tuberculosis.10

The treatment resides in the administration of antitubercular drugs or, depending on structural alterations of the organ, partial or total exeresis. Common pyrazinamide-rifampicin-isoniazid regimen is harmless to renal function once these are hepatic metabolism drugs and biliary excretion. Special attention, however, should be given whenever the use of streptomycin, ethambutol and aminoglycosides is made necessary. Since they are renal excretion drugs, dosage adjustment is recommended.1

It is a serious illness, nevertheless the prognostic is usually good with a low date rate. Its early identification as well as the start of proper therapeutic treatment in advance are of paramount importance.

Learning points.

It is important to differentiate between complicated urinary tract infection accompanied by systemic symptoms and uncomplicated urinary tract infection, which is responsible for a majority of the events.

The routine culture should always be directed to cases which are refractory to treatment and recurrences. The absence of bacterial growth in the presence of leucocyturia should lead the investigation to search for mycobacteria and fungi.

The diagnosis for renal tuberculosis should be confirmed with specific culture for M tuberculosis. A positive bacilloscopy is not a guarantee that the infection may not be secondary to another mycobacteria.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Eastwood JB, Corbishley GM, Grange JM. Tuberculosis and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:1307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figueiredo AA, Lucon AM, Junior RF, et al. Epidemiology of tuberculosis urogenital worldwide. Int J Urol 2008;15:827–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbara A, Davidson RN. Etiology and management of genitourinary tuberculosis. Nat Rev Urol 2011;8:678–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cek M, Lenk S, Naber KG, et al. EAU guidelines for the management of genitourinary tuberculosis. Eur Urol 2005;48:353–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange C, Mori T. Advances in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Respirology 2010;15:220–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutiérrez-Adrianzén OA, Silva SL, Corsino GA, et al. End-stage renal disease due to delayed diagnosis of renal tuberculosis: a fatal case report. Braz J Infect Dis 2007;11:169–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt C, Lodha S. Paraspinal sinuses? Do remember renal tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep 2012;10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5445, Published 27 March 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adhya AK, Dey P. Cytologic detection of urinary tract tuberculosis. Acta Cytol 2010;54:653–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rui X, Li XD, Cai S, et al. Ultrasonographic diagnosis and typing of renal tuberculosis. Int J Urol 2008;15:135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen WI. Genitourinary tuberculosis review of 102 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1974;53:377–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]