Abstract

A 47-year-old man presented with symptoms of fever and productive cough secondary to a left upper lobe pneumonia. He had received more than three courses of antibiotics over a 2-year period. Review of serial radiographic exams including chest x-ray and CT scans revealed consolidation of the left upper lobe. Lack of response to antibiotics prompted invasive testing with bronchoscopy which revealed a growth in the left main bronchus. Histopathology revealed squamous cell carcinoma.

Background

A non-resolving pneumonia may be the first manifestation of lung malignancy. The term non-resolving pneumonia has been variably defined by investigators and early descriptions were based principally on clinical examination findings. In 1991, Kirtland and Winterbauer1 added radiographic criteria and ‘slowly resolving pneumonia’ was defined as ‘clearing of radiographic infiltrate less than 50% in 2 weeks or incomplete clearing at 4 weeks’ in a patient who has clinically responded to antibiotics. Other authors have defined it more broadly as radiographic infiltrate that is slow to resolve after optimal antibiotic therapy given for at least 10 days.2 Approximately 20% of presumed non-resolving community-acquired pneumonia is due to non-infectious causes.3 Aetiologies like inflammatory, drug-induced and vascular disorders, as well as neoplasm can mimic pneumonia. Our case highlights the need for an aggressive search for the cause of non-resolving radiographic infiltrate despite appropriate antibiotic coverage.

Case presentation

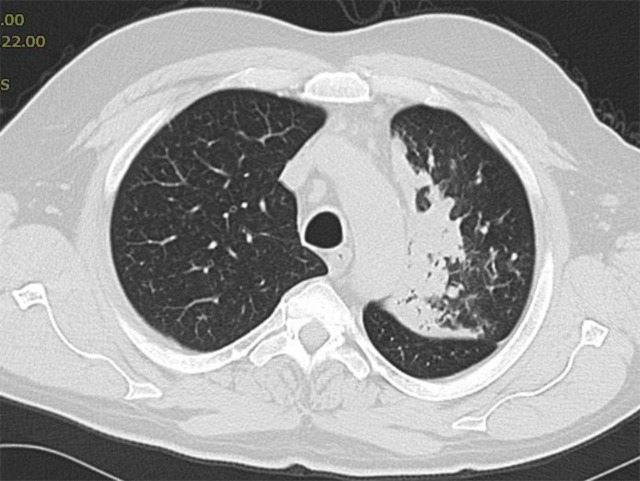

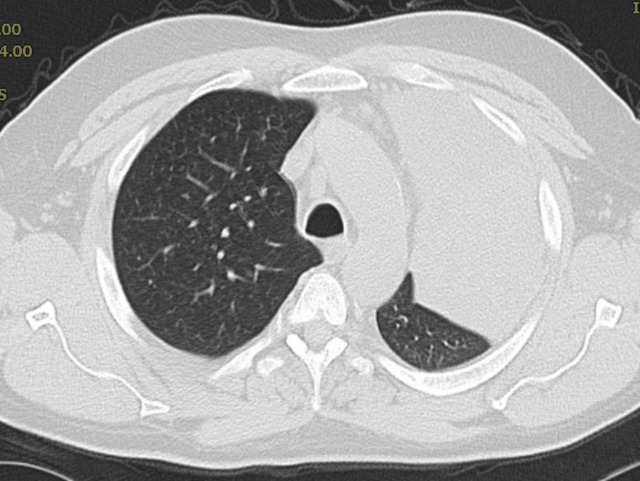

A 47-year-old Caucasian man was hospitalised with a history of cough and purulent sputum production for 4 months, and fever of 1 week duration. Over the previous 4 months, he had received two courses of azithromycin and one course of levofloxacin for a diagnosis of left upper lobe pneumonia. Sputum cultures were non-diagnostic on all occasions. Initial chest x-ray, as well as CT scan done as an outpatient had revealed left upper lobe consolidation (figure 1). A follow-up CT scan repeated after the three courses of antibiotics had shown worsening opacification of the involved area (figure 2). He denied any sick contacts, recent travel, exposure to dust, mould or pets. The patient was an active smoker, smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes a day for almost 30 years. He also had a history of pneumonia diagnosed 2 years back, was not aware which antibiotic was used at that time. Family history was positive for breast cancer in his mother. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 100.1°F, pulse was 116/min, respiratory rate was 24/min, blood pressure 136/84 mm Hg and oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. He had poor dental hygiene. There was no pallor, icterus, lymphadenopathy or jugular venous distension. Respiratory system examination revealed decreased air entry with wheezing in the left upper zone.

Figure 1.

CT scan of chest showing left upper lobe consolidation.

Figure 2.

CT scan of chest showing worsening consolidation.

Investigations

Laboratory work-up showed a white cell count of 19×10−9/l. Serum sodium was 129 mEq/l. Blood cultures were negative and sputum cultures revealed mixed respiratory flora. Urine legionella antigen test was negative. HIV test was negative. Chest x-ray revealed left upper lobe consolidation.

Differential diagnosis

Pneumonia caused by resistant organism or atypical pathogen like mycobacterium, fungus and nocardia.

Neoplasm.

Treatment

On account of recurrent symptoms and worsening radiological abnormalities, a flexible bronchoscopy was performed. It revealed a cauliflower-like growth in the left main bronchus (figure 3). Bronchoscopic biopsy was performed which revealed non-small cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and negative for cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20 and thyroid transcription factor-1 supporting the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. Positron emission tomography scan revealed no evidence of extrathoracic metastatic disease. The patient underwent a left pneumonectomy. Intraoperatively, a massive and densely adherent tumour was detected. Surgical margins were negative for tumour. Excised lymph nodes were also negative.

Figure 3.

Bronchoscopic visualisation of tumour (arrow) in the left main bronchus.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperative recovery was uneventful. He is following up with his oncologist for scheduled cancer surveillance evaluations.

Discussion

Slow or non-resolving pneumonia may be caused by multiple factors acting singly or in combination. These include age, comorbidities, severity of the pneumonia and nature of the infectious agent. Other factors like poor host immunity, drug-resistant bacteria and atypical pathogens like mycobacterium, nocardia, actinomyces or fungi need to be considered in a patient showing poor response to standard antibiotic therapy.4 In some cases sequestration of infectious foci like empyema or lung abscess may prevent adequate concentration of antibiotics from reaching the site of infection. Neoplasms like broncho-alveolar carcinoma or lymphoma may also mimic an infectious process.5 6 Conversely, bronchogenic carcinoma may itself cause compression of the airway with resultant postobstructive pneumonia. In most case series, the frequency of endobronchial carcinoma as a cause of non-resolving pneumonia is relatively low.4 Our patient was treated with outpatient antibiotics as per Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines.7 He also had a long smoking history. Persistent symptoms and worsening radiological abnormalities prompted bronchoscopy and biopsy which clinched the diagnosis.

CT scan of the chest is a very useful tool in diagnosis and management of lung disease. In one case series, the reported sensitivity in differentiating infectious from non-infectious causes of parenchymal lung disease was as high as 90%.8 However, in our case, two CT scans done as an outpatient failed to reveal the underlying tumour, probably because the mass was endobronchial in location rather than involving the lung parenchyma.

Learning points.

Broad differential diagnoses applied to pneumonia not responding to routine antibiotic therapy. These include infectious, inflammatory or neoplastic processes.

Non-resolving pneumonia may be the first manifestation of lung malignancy and should be considered early in patients with a history of smoking.

Bronchoscopy with biopsy will lead to accurate diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Kirtland SH, Winterbauer RH. Slowly resolving, chronic and recurrent pneumonia. Clin Chest Med 1991;12:303–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. The approach to non-resolving pneumonia in the elderly. Semin Respir Infect 1993;8:59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arancibia F, Ewig S, Martinez JA, et al. Antimicrobial treatment failures in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: causes and prognostic implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menendez M, Torres A. Treatment failure in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2007;132:1348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumont P, Gasser B, Rouge C, et al. Bronchoalveolar carcinoma: histopathologic study of evolution in a series of 105 surgically treated patients. Chest 1998;113:391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadranel J, Wislez M, Antoine M. Primary pulmonary lymphoma. Eur Respir J 2002;20:750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzeuto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American thoracic Society Consensus Guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:S27–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomiyama N, Muller NL, Johkoh T, et al. Acute parenchymal lung disease in immunocompetent patients: diagnostic accuracy of high resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:1745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]