Abstract

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is an uncommon complication of malignant disease caused by the obstruction of venous blood flow in the SVC. When present, a diagnosis of lung cancer or lymphoma will be made in approximately 95% of cases. Although other malignant diseases are occasionally associated with SVC, its occurrence in patients with prostate cancer is rare. We present a case of a patient presenting with SVC obstruction who was subsequently diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma. The patient has been successfully treated with GnRH agonist. This case reflects the importance of a full clinical assessment and pathological confirmation of suspected tumour prior to treatment.

Background

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death among men.1 Although one in six men residing in the USA will develop prostate cancer during their lifetime, the risk of death from this disease is only 2.9%,2 3 reflecting the remarkable heterogeneity in malignant properties of the disease. For many, its presence will have little clinical consequence.

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is an uncommon complication of malignant disease caused by the obstruction of venous blood flow in the SVC. When present, a diagnosis of lung cancer or lymphoma will be made in approximately 95% of cases.4 Although other malignant diseases are occasionally associated with SVC, its occurrence in patients with prostate cancer is rare.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old Caucasian man with a 40-pack-year history of cigarette smoking presented with progressive lower-back pain of 2 months duration. An MRI scan revealed an irregular contour of the T12 and L5 vertebral bodies. In addition, an abnormal bone marrow fat-signal pattern throughout the visualised osseous structures was noted and considered suspicious for metastatic tumour. Also present were diffusely enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes with the largest collection measuring approximately 6 cm in diameter.

Because of the presence of intractable back pain as well as the concerning MRI findings, the patient was admitted for medical management. In addition to the skeletal pain, he also complained of shortness of breath, palpitations, urinary frequency and progressive unintentional weight loss.

On physical examination he had a ruddy complexion with general swelling of the tissues of his head and neck. There was also significant venous distension around the upper chest and neck. Lung sounds were clear bilaterally, and heart sounds were unremarkable.

Investigations

Laboratory studies showed a white blood count of 11.4 k/μl, platelet count of 502 k/μl and a haemoglobin concentration of 13.3 g/dl. Sodium was 141 mmol/l, potasium 5.0 mmol/l, alkaline phosphatase 443 unit/l, lactate dehydrogenase 490 unit/l (313–618), carcinoembryonic antigen 0.8 ng/ml (0.0–5.0) and carbohydrate antigen 19–97.5 IU/ml (0.0–35.0). Remarkably, a prostate specific antigen (PSA) was 87 ng/ml (0.0–4.0).

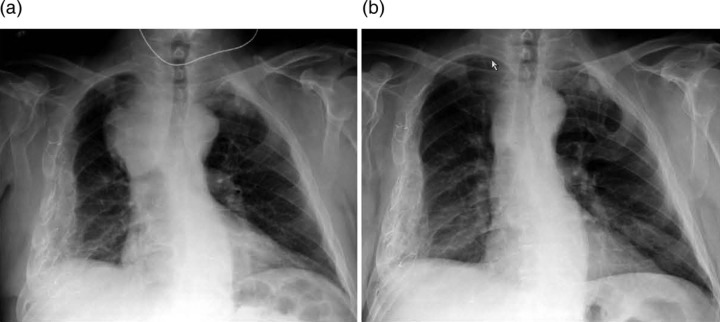

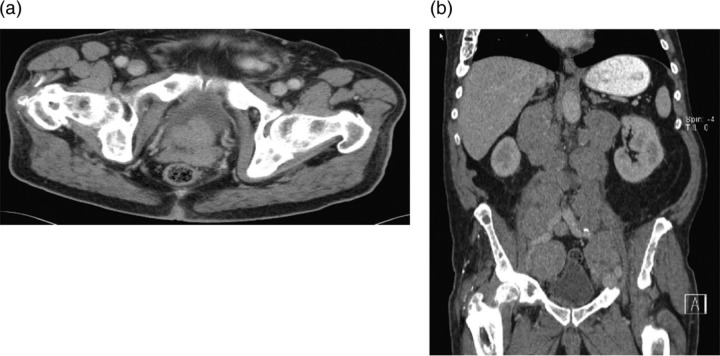

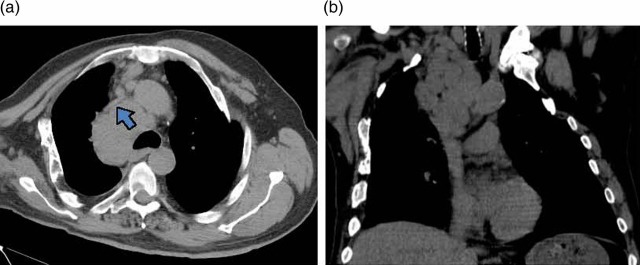

Chest x-ray revealed a right paratracheal mass (figure 1A). A chest CT scan demonstrated mediastinal lymphadenopathy extending into the right supraclavicular region of the neck and compressing the SVC (figure 2). A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed bulky retroperitoneal and pelvic lymphadenopathy, an asymmetrically enlarged prostate gland (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Chest x-rays taken on admission and a month later. (A) Admission chest x-ray demonstrating a right paratracheal soft tissue mass. (B) Chest x-ray after one leuprolide treatment demonstrating significant reduction in the mediastinal mass.

Figure 2.

A chest CT scan without intravenous contrast demonstrating (A) superior vena cava (indicated by a bold arrow) compressed by bulky, confluent mediastinal lymph nodes, (B) mediastinal lymphadenopathy extending into the supraclavicular region of the neck without evidence of a bronchial or parenchymal lung mass.

Figure 3.

An abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast demonstrating (A) an asymmetric, enlarged prostate gland protruding into the bladder, (B) massive, extensive retroperitoneal, pelvic lymphadenopathy.

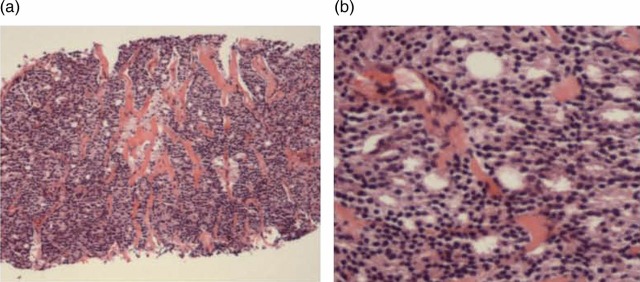

A biopsy of one of the pelvic lymph nodes demonstrated an extensive infiltration by a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with a positive staining reaction for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase (figure 4).

Figure 4.

A core biopsy fragment of a pelvic lymph node demonstrates: (A) total replacement of lymphoid tissue by a metastatic adenocarcinoma; (B) glandular structures formed by well-differentiated prostate adenocarcinoma.

Differential diagnosis

Lung cancer

Malignant lymphoma

Prostate cancer.

Treatment

Upon achieving pain control, the patient was treated with partial androgen ablation hormonal therapy (leuprolide) and a bisphosphonate.

Outcome and follow-up

The chest x-ray obtained 1 month later demonstrated substantial reduction in the mediastinal mass and the patient's presenting pain and other clinical symptoms almost completely resolved (figure 1B).

Discussion

Mediastinal adenopathy causing SVC syndrome is rarely encountered in the setting of metastatic prostate cancer. Although we did not have tissue obtained directly from the mediastinal lymph node, the prompt and gratifying reduction in the mediastinal adenopathy observed in this patient after initial treatment with leuprolide indicates that prostate adenocarcinoma resulted in SVC obstruction.

Rice and colleagues4 described features of the SVC syndrome in a series of 47 cases arising from various tumour types. The most common clinical symptom was face or neck swelling (82%), as was seen in our patient.

In a review of published reports, there were a few other cases of SVC syndrome or intrathoracic lymphadenopathy with prostate cancer,5–12 but in these cases the histopathology typically was described as being that of a poorly or moderately differentiated carcinoma, rather than the well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, as reported in our case. The mechanisms of metastasis are complex and incompletely understood, but it is apparent from our case that a favourable histology alone does not preclude widespread and aggressive metastatic disease. In this regard, genetic13 and microenvironmental factors14 15 have been shown to be instrumental in the development of aggressive metastatic disease.

Physicians have relied on the Gleason score, staging system and PSA to estimate prognosis for patients with prostate cancer. This case illustrates that despite a well-differentiated histological pattern, prostate cancer can exhibit widespread and destructive metastases leading to a very adverse prognosis. The genetic and molecular correlates of such aggressive disease remain to be elucidated.

Learning points.

Superior vena cava syndrome can be caused by prostate cancer along with widespread, generalised lymphadenopathy.

Well-differentiated prostate adenocarcinoma can result in widespread destructive metastasis.

As histology alone is not enough to predict biological behaviour of malignancy, genetic and microenvironmental factors may play a critical role in cancer progression.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:225–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorr VJ, Williamson SK, Stephens RL. An evaluation of prostate-specific antigen as a screening test for prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:2529–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2004 based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site 2007. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004

- 4.Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi S, Hamanaka Y, Sueda T, et al. Thymic metastasis from prostatic carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today 1993;23:632–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGarry RC. Superior vena cava obstruction due to prostate carcinoma. Urology 2000;55:436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montalban C, Moreno MA, Molina JP, et al. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate presenting as a superior vena cava syndrome. Chest 1993;104:1278–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moura FM, Garcia LT, Castro LP, et al. Prostate adenocarcinoma manifesting as generalized lymphadenopathy. Urol Oncol 2006;24:216–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Old SE. Superior vena cava obstruction in prostate cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1999;11:352–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyan B, Engin H, Yalcin S. Generalized lymphadenopathy: a rare presentation of disseminated prostate cancer. Med Oncol 2002;19:177–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park Y, Oster MW, Olarte MR. Prostatic cancer with an unusual presentation: polymyositis and mediastinal adenopathy. Cancer 1981;48:1262–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tohfe M, Baki SA, Saliba W, et al. Metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma presenting with pulmonary symptoms: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J 2008;1:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauffman EC, Robinson VL, Stadler WM, et al. Metastasis suppression: the evolving role of metastasis suppressor genes for regulating cancer cell growth at the secondary site. J Urol 2003;169:1122–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung LW, Baseman A, Assikis V, et al. Molecular insights into prostate cancer progression: the missing link of tumor microenvironment. J Urol 2005;173:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heresi GA, Wang J, Taichman R, et al. Expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in prostate cancer presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy: report of a case, review of the literature, and analysis of chemokine receptor expression. Urol Oncol 2005;23:261–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]