Abstract

Liver transplantation (LT) reportedly prolongs the survival of patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP), a fatal hereditary systemic amyloidosis caused by mutant transthyretin (TTR). However, what happens in systemic tissue sites long after LT is poorly understood. In the present study, we report pathological and biochemical findings for an FAP patient who underwent LT and died from refractory ventricular fibrillation more than 16 years after FAP onset. Our autopsy study revealed that the distributions of amyloid deposits after LT were quite different from those in FAP amyloidogenic TTR V30M patients not having had LT and seemed to be similar to those observed in senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA), a sporadic systemic amyloidosis derived from wild-type (WT) TTR. Our biochemical examination also revealed that this patient's cardiac and tongue amyloid deposits derived mostly from WT TTR. We propose that FAP patients after LT may suffer from SSA-like WT TTR amyloidosis in systemic organs.

Background

Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP) is an autosomal-dominant form of fatal hereditary systemic amyloidosis, the most common cause of which is mutant (MT) transthyretin (TTR).1 2 TTR is a plasma protein synthesised mainly in the liver but also in the choroid plexus of the brain and retinal pigment epithelial cells. To date, more than 120 TTR mutations have been identified, most of which result in development of FAP.2 Sensorimotor polyneuropathy, autonomic dysfunction, heart and kidney failure, gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorders and ocular manifestations that led to death within an average of 10 years have been documented in patients with FAP caused by amyloidogenic TTR (ATTR) V30M, which is the most common FAP genotype worldwide.1

Liver transplantation (LT) reportedly halts the progression of clinical manifestations of FAP ATTR V30M.3 Exchange of the diseased liver in the FAP patient with a healthy liver causes MT TTR in the bloodstream to be replaced by wild-type (WT) TTR. According to data in the Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy World Transplant Registry (http://www.fapwtr.org), approximately 120 LTs have been performed annually for FAP throughout the world. Certain studies have shown that LT prolonged the survival of FAP ATTR V30M patients who had been selected carefully for LT.3 4 Some patients also had progression of cardiac amyloidosis after LT,5 which was due to continued formation of amyloid mainly derived from WT TTR that was secreted from the normal liver.6 However, what happens in systemic tissue sites in patients after LT is poorly understood.

The present study reports clinical and autopsy findings for an FAP ATTR V30M patient who was the first Japanese patient to undergo cadaveric donor LT and survived more than 16 years after FAP onset. Also, to our knowledge, this report is the first full autopsy study of an FAP patient surviving more than 13 years after LT. We believe that this information will help understanding of the long-term effects of LT on FAP.

Case presentation

A 28-year-old man presented with constipation alternating with diarrhoea, a weight decrease from 70 to 56 kg during 2 years, erectile dysfunction, urinary disturbance, thermal anaesthesia and paraesthesia in the lower limbs. Constipation alternating with diarrhoea and erectile dysfunction first appeared at age 26. He was diagnosed with FAP ATTR V30M on the basis of histological findings in gastric biopsy specimens and PCR–restriction fragment length polymorphism genetic analyses.

Two years and 6 months after FAP onset, in 1993, he underwent an LT from a cadaveric donor at Huddinge Hospital, Sweden. At that time, clinical and laboratory findings showed no cardiac and renal involvement (table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory findings before and after LT

| Variable | 3 months before LT (1993) | 8 months after LT (1994) | 37 months after LT (1997) | 116 months after LT (2003) | 146 months after LT (2006) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28 | 29 | 31 | 38 | 41 |

| Time from FAP onset (years) | 2.3 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 12.2 | 14.7 |

| FAP clinical score* | |||||

| Total | 11 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 23 |

| I. Sensory abnormalities | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| II. Motor function | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| III. Autonomic disorders | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| IV. Visceral organ impairment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12 |

| mBMI score (BMI×albumin) | 793.5 | 667.1 | 754.4 | 828.6 | 776.2 |

| Cardiac symptoms and ECG | WNL | WNL | WNL | First-degree AV block | General fatigue, pacemaker implantation for complete AV block IVSTd: 13.8 mm, E/A: 1.21, TMF DcT: 150 ms, E/e′: 10.27, %FS: 35.4%, granular sparkling appearance (+) |

| Echocardiography | WNL | WNL (IVSTd: 10.4 mm, %FS 54.0%) | NE | IVSTd: 11.4 mm, E/A: 1.85, TMF DcT: 125 ms, %FS: 42.0% | |

| Cr (mg/dl) and proteinuria | 0.70 (−) | 0.89 (−) | 0.80 (−) | 0.81 (−) | 1.05 (−) |

| Eye findings | WNL | WNL | NE | Mild amyloid deposits on pupil | Mild vitreous opacity |

*FAP clinical score was used to assess the clinical symptoms of FAP.7

AV, atrioventricular; BMI, body mass index; Cr, serum creatinine concentration; DcT, deceleration time; E/A, ratio of peak early filling velocity to late diastolic atrial filling velocity; E/e′, ratio of early diastolic transmitral velocity to early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity; FAP, familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy; FS, fractional shortening; IVSTd, interventricular septal thickness in diastole; LT, liver transplantation; mBMI, modified body mass index; NE, not examined; TMF, transmitral flow; WNL, within normal limits.

After LT, his symptoms were stable. However, in 2003, 9 years and 8 months after LT, he developed first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block. In 2006, 12 years and 2 months after LT, he developed a complete AV block with generalised fatigue, and he underwent pacemaker implantation. Cardiac catheterisation revealed a normal ejection fraction (79.9%) but an increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (20 mm Hg), which indicated left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. His kidney function was stable even after LT (table 1). Although he had no eye involvement before and at 8 months after LT, he developed mild pupillary amyloid deposition without irregularity in 2003 and mild vitreous opacity in 2006 (table 1). He also had alcoholism, which was gradually worsening. Thirteen years and 10 months after the LT, which was 16 years and 4 months after FAP onset, he died from refractory ventricular fibrillation. At that time, he also had hypokalaemia (2.8 mEq/l), probably the result of alcoholism.

Investigations

Autopsy revealed that the heart of the patient weighed 430 g. The ventricular walls were 18.0 mm thick on the left and 4.0 mm on the right. The liver was fatty, showed congestion and weighed 1340 g but evidenced no specific indications of chronic graft rejection. The lungs (right: 1319 g and left: 1307 g) also showed congestion. Inflammation and atrophy of the pancreas indicated alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Severe dilation of the bladder, which was probably due to autonomic dysfunction, was also noted.

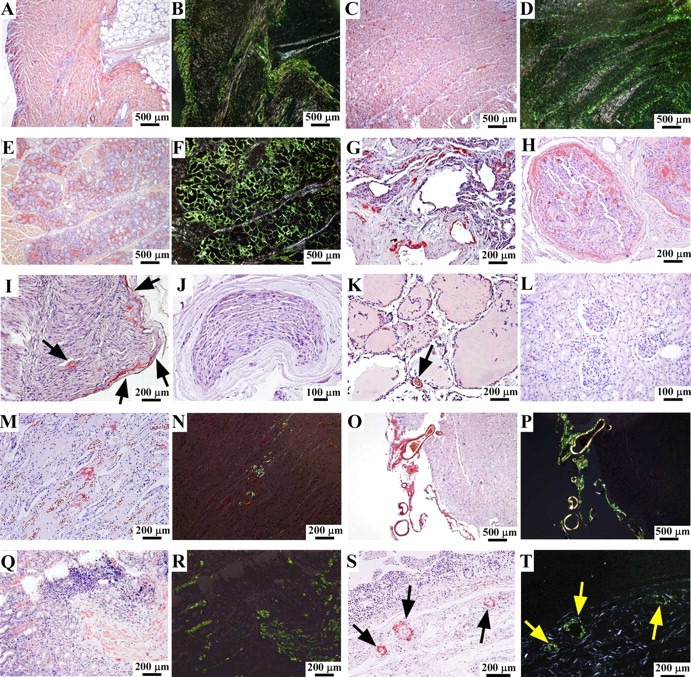

Microscopic examinations revealed severe amyloid deposits in the heart (figure 1A–D). Severe amyloid deposits were also unexpectedly found in the tongue, especially the minor salivary gland (figure 1E,F). The lung evidenced mild-to-moderate amyloid deposits in the alveoli and vascular walls (figure 1G). Although moderate-to-severe and mild-to-moderate amyloid deposits were found in the thoracic sympathetic nerve and sciatic nerve, respectively (figure 1H,I), the sural nerve had no amyloid deposits (figure 1J). Mild amyloid deposits were detected in the vascular walls of the thyroid gland (figure 1K), but almost no amyloid deposition was found in the thyroid interstitium, a usual site of severe amyloid deposition in FAP ATTR V30M patients without LT.8 Also, the kidneys manifested no amyloid deposition except for mild-to-moderate deposits in the papilla (figure 1L–N). We also analysed brain specimens and found moderate-to-severe amyloid deposits in the leptomeninges and vascular walls (figure 1O,P). Severe amyloid deposits in the stomach were detected at the onset of FAP in 1993 (figure 1Q,R), but in stomach autopsy specimens, amyloid deposits were limited to the vascular walls (figure 1S,T). In other autopsy specimens of the GI tract such as small and large intestines, amyloid deposits were largely limited in the vascular walls. Ocular tissues were not examined at autopsy.

Figure 1.

Distribution of amyloid deposits after liver transplantation. (A, B) Right ventricle of the heart, (C, D) left ventricle of the heart, (E, F) tongue, (G) lung, (H) thoracic sympathetic nerve, (I) sciatic nerve, (J) sural nerve, (K) thyroid gland, (L) renal cortex, (M, N) renal papilla, (O, P) temporal lobe of the brain, (Q, R) gastric biopsy specimens at the time of diagnosis in 1993, and (S, T) stomach. (A, C, E, G–M, O, Q, S) Congo-red staining, (B, D, F, N, P, R, T) Congo-red staining viewed under polarised light, (I, K, S, T) arrows indicate amyloid deposits.

To determine the contribution of WT TTR to the formation of amyloid fibrils, which were continuously secreted into the bloodstream even after LT, we investigated amyloid fibrils isolated from frozen cardiac and tongue specimens via liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). On LC–MS/MS analysis, we investigated the mass peaks of tryptic peptides (TTR 22–34) including the position 30 as described previously.9 The abundance of these peptides was calculated from peak areas of ion chromatograms of TTR 22–34 peptides. These analyses revealed that 81% of the cardiac amyloid and 84% of the tongue amyloid were derived from WT TTR.

Treatment

Two years and 6 months after FAP onset, in 1993, he underwent an LT from a cadaveric donor at Huddinge Hospital, Sweden.

Outcome and follow-up

Thirteen years and 10 months after the LT, which was 16 years and 4 months after FAP onset, he died from refractory ventricular fibrillation.

Discussion

The present report provides, for the first time to our knowledge, direct pathological data in systemic tissue sites for an FAP patient surviving more than 13 years after LT. He underwent LT when he was in relatively good clinical condition, such as early age, short duration of disease and no cardiac symptoms, and he survived for 16 years and 4 months from the onset of FAP. His survival period was much longer than the recently reported survival period (11.8±2.0 years) of non-transplanted FAP ATTR V30M patients with a disease onset before the age of 50 years who had been studied at Kumamoto University Hospital between 1990 and 2010.4 Although clinical and laboratory findings were stable until 9 years and 8 months after LT, asymptomatic amyloid deposits might precede the appearance of abnormal findings on the clinical examinations such as ECG, echocardiography and biomarkers.

Our detailed histopathological examinations revealed that distributions of amyloid deposits after LT were quite different from those in FAP ATTR V30M patients not having had LT8 and, except for deposits in sympathetic and sciatic nerves, seemed to be similar to those in patients with senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA), a sporadic systemic amyloidosis resulting from WT TTR.10 11 Our biochemical examination also revealed that this patient's cardiac and tongue amyloid deposits were mostly derived from WT TTR, which must have been secreted from the normal liver graft. In addition, previous studies also reported that distributions of amyloid deposits of late-onset FAP cases were similar to SSA12 and that more than half of cardiac amyloid was composed of WT TTR in those cases.13

Why WT TTR amyloidosis, which is usually found in the elderly, occurs in relatively young FAP patients after LT remains to be discovered. One possibility is that older amyloid deposits formed by MT TTR before LT may act as a nidus, which is well known to enhance polymerisation of proteins,14 and additional WT TTR amyloid fibrils may form because of nucleation-dependent polymerisation after LT. Another possibility is that older MT TTR amyloid deposits may induce overproduction of basement membrane components, which may promote increased amyloid formation, as our previous study of FAP patients without LT showed.15

In conclusion, we propose that FAP patients after LT may suffer from SSA-like WT TTR amyloidosis in systemic organs, which results from MT TTR amyloid deposits that were present before LT.

Learning points.

This patient underwent liver transplantation (LT) when he was in relatively good clinical condition, such as early age, short duration of disease and no cardiac symptoms, and he survived for 16 years and 4 months from the onset of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP). His survival period was much longer than the recently reported survival period of non-transplanted FAP amyloidogenic transthyretin (ATTR) V30M patients.

Although clinical and laboratory findings were stable until 9 years and 8 months after LT, asymptomatic amyloid deposits might precede the appearance of abnormal findings on the clinical examinations such as ECG, echocardiography and biomarkers.

Distributions of amyloid deposits after LT were quite different from those in FAP ATTR V30M patients not having had LT and seemed to be similar to those in patients with senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA), a sporadic systemic amyloidosis resulting from WT TTR.

This patient's cardiac and tongue amyloid deposits were mostly derived from WT TTR, which must have been secreted from the normal liver graft.

FAP patients after LT may suffer from SSA-like WT TTR amyloidosis in systemic organs, which results from MT TTR amyloid deposits that were present before LT.

Footnotes

Contributors: KO, MU and YA: diagnosis, design of the study, data collection, therapy, analysis of data and writing the manuscript. TO, YM, TY, YO, KA and YI: diagnosis, therapy and data collection. SK, HJ, MY, FK and SI: analysis of data.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Ando Y, Nakamura M, Araki S. Transthyretin-related familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1057–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeldenrust S, Benson MD. Familial and senile amyloidosis caused by transthyretin. In: Alvarado M, Kelly JW, Dobson CM, eds. Protein misfolding diseases: current and emerging principles and therapies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010:795–815. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suhr OB, Friman S, Ericzon BG. Early liver transplantation improves familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy patients’ survival. Amyloid 2005;12:233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita T, Ando Y, Okamoto S, et al. Long-term survival after liver transplantation in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology 2012;78:637–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubrey SW, Davidoff R, Skinner M, et al. Progression of ventricular wall thickening after liver transplantation for familial amyloidosis. Transplantation 1997;64:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yazaki M, Mitsuhashi S, Tokuda T, et al. Progressive wild-type transthyretin deposition after liver transplantation preferentially occurs onto myocardium in FAP patients. Am J Transplant 2007;7:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tashima K, Ando Y, Ando E, et al. Heterogeneity of clinical symptoms in patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP TTR Met30). Amyloid 1997;4:108–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Yi S, Kimura Y, et al. Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy type 1 in Kumamoto, Japan: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Hum Pathol 1991;22:519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuchiya A, Yazaki M, Kametani F, et al. Marked regression of abdominal fat amyloid in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy during long-term follow-up after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2008;14:563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitkänen P, Westermark P, Cornwell GG., III Senile systemic amyloidosis. Am J Pathol 1984;117:391–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueda M, Horibata Y, Shono M, et al. Clinicopathological features of senile systemic amyloidosis: an ante- and post-mortem study. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1533–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koike H, Misu K, Sugiura M, et al. Pathology of early- vs late-onset TTR Met30 familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology 2004;63:129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koike H, Ando Y, Ueda M, et al. Distinct characteristics of amyloid deposits in early- and late-onset transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol Sci 2009;287:178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris AM, Watzky MA, Finke RG. Protein aggregation kinetics, mechanism, and curve-fitting: a review of the literature. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1794:375–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misumi Y, Ando Y, Ueda M, et al. Chain reaction of amyloid fibril formation with induction of basement membrane in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. J Pathol 2009;219:481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]