Abstract

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) is a novel minimally invasive procedure useful for the evaluation and diagnosis of mediastinal lymph nodes and the lung parenchymal lesions. A 75-year-old woman diagnosed as a case of infiltrating duct adenocarcinoma of left breast 15 years back for which she underwent a modified radical mastectomy followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The patient presented to us with haemoptysis. During EBUS, the enlarged left hilar lymph node was seen to be eroding into the left pulmonary artery leading to a filling defect in the left pulmonary artery. This filling defect was first sampled by EBUS-guided TBNA followed by sampling of left hilar lymph node. The results of cytomorphology revealed malignancy which was compatible with a metastasis from a carcinoma breast. EBUS-TBNA is a novel, safe and minimally invasive procedure with a few complications.

Background

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) is a novel minimally invasive procedure useful for the evaluation and diagnosis of mediastinal lymph nodes and the lung parenchymal lesions. Two types of EBUS are currently available. Linear EBUS enables real-time TBNA of mediastinal lymph nodes and juxtabronchial lesions under the guidance of ultrasound. Radial EBUS allows evaluation of central airways (including airway invasion) and sampling of lung parenchymal lesions. Ultraminiature radial probe is used for sampling of peripheral lung lesions while radial balloon probe is used for central airway evaluation. We present a rare case of metastatic breast cancer to the left hilar lymph node eroding directly into the left pulmonary artery diagnosed by EBUS-guided TBNA.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old woman was diagnosed as a case of infiltrating duct adenocarcinoma of left breast 15 years back for which she underwent a modified radical mastectomy (MRM). MRM was followed by 25 cycles of radiotherapy. She also received chemotherapy in the form of tamoxifen for 5 years. Thereafter, she remained asymptomatic for almost 6 years. The patient presented to another hospital in October 2011 with complaints of left-sided chest pain and mild haemoptysis. Her chest x-ray did not reveal any significant abnormality. She underwent a contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax, which revealed a thrombus in the descending branch of the left pulmonary artery along with upto 1 cm left hilar lymph node. No significant parenchymal lesion was seen to explain haemoptysis. Bronchoscopy was done, which revealed bleeding from anterior segment of the left upper lobe bronchus. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was taken from the involved segment and was sent for microbiological and cytological examination. BAL fluid was negative for infective organisms and malignancy. Ultrasonography and Doppler imaging of the deep-venous system of the legs was normal and did not reveal any thrombus. The patient was put on conservative management and discharged in a week after the haemoptysis was controlled. The patient was planned to be started on oral anticoagulants for left pulmonary artery thrombus but patient was lost to follow-up.

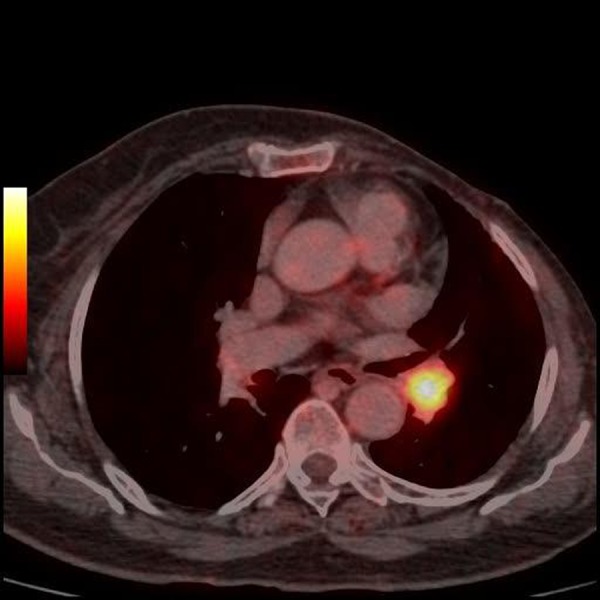

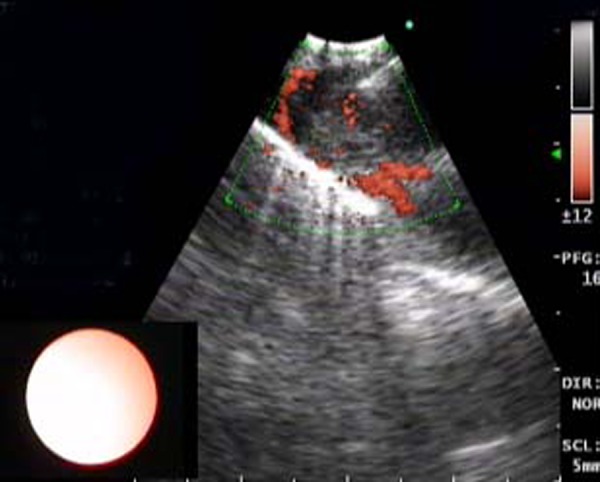

She was asymptomatic for the next 6 months but presented to our hospital with complaints of increased haemoptysis of around 200 ml in 24 h in May 2012. A chest x-ray was done, which was again normal. Since the patient had a history of breast malignancy and a previous contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax showing a pulmonary artery thrombus, a positron emission tomography (PET) CT thorax with CT pulmonary angiography was planned in the same sitting. CT pulmonary angiography revealed a non-enhancing hypodense filling defect in the descending branch of the left pulmonary artery, which was contiguous with the enlarged left hilar lymph node (figures 1–3). PET CT thorax revealed a fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid (SUV of 8.9) filling defect in the descending branch of left pulmonary artery along with FDG-avid (SUV of 10.4) left hilar lymph node (figures 4 and 5). EBUS-guided TBNA was planned to sample the left hilar lymph node. During EBUS, the enlarged left hilar lymph node was seen to be eroding into the left pulmonary artery leading to a filling defect in the left pulmonary artery (figures 6 and 7). This filling defect was first sampled by EBUS-guided TBNA (figure 8) followed by sampling of left hilar lymph node. The slides were sent for cylological examination. Some of the slides from each sampled site were air dried while others were fixed in 95% alcohol. The procedure was uneventful. In spite of sampling the thrombus in the pulmonary artery, there was no significant bleeding postprocedure. Care was taken not to do the jabbing movements when the dimpled part of EBUS fine-needle aspiration cytology needle was near the vessel wall. Patient was stable after the procedure. The cytological examination revealed malignancy which was compatible with metastasis from carcinoma breast (figure 9). Following the diagnosis the patient was given first cycle of chemotherapy (Paclitaxel) which was tolerated well by the patient.

Figure 1.

CT pulmonary angiography showing enlarged left hilar lymph node contiguous with the thrombus in the descending branch of left pulmonary artery.

Figure 2.

CT pulmonary angiography showing thrombus in the descending branch of left pulmonary artery.

Figure 3.

Coronal section of CT pulmonary angiography showing thrombus in the descending branch of left pulmonary artery.

Figure 4.

Positron emission tomography scan showing fludeoxyglucose-avid left hilar lymph node.

Figure 5.

Coronal section of positron emission tomography scan showing fludeoxyglucose-avid thrombus in the descending branch of left pulmonary artery.

Figure 6.

Endobronchial ultrasound showing left hilar lymph node contiguous with the thrombus in the left pulmonary artery.

Figure 7.

Endobronchial ultrasound showing filling defect in the left pulmonary artery.

Figure 8.

Sampling of the thrombus in the descending branch of left pulmonary artery by endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration.

Figure 9.

Cluster of tumour cells in a background of blood (May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain).

Differential diagnosis

Pulmonary embolism

Tubercular mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has tolerated the chemotherapy well and is being continued on chemotherapy.

Discussion

EBUS TBNA enables sampling of upper and lower paratracheal (stations 2 and 4), subcarinal (station 7), hilar (station 10) and interlobar (station 11) lymph nodes1 with a sensitivity of about 90% and a specificity of 100%.1–5 The yield of EBUS-guided TBNA is reported to be higher in comparison with the yield with the conventional TBNA which is a blind procedure.6 Hence, in our case we decided to sample the hilar lymph node using the EBUS TBNA. This hilar lymph node was FDG avid on PET scan. The overall sensitivity of PET scan for determining malignant involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes is 80–84% while the specificity is 70–89%.1 7 However, lymph nodes showing no FDG uptake are not always free of malignancy. Up to 10% of patients showing no FDG-avid mediastinal lymph nodes on PET scan may have hilar or mediastinal metastases.8

On EBUS, the left hilar lymph node was found to be eroding into the left pulmonary artery. The filling defect in the left pulmonary artery and the left hilar lymph node were sampled. The cytomorphology revealed malignancy compatible with metastases from a carcinoma breast. Such cases of metastatic mediastinal lymph nodes invading into the pulmonary artery are rare and may sometimes mimic pulmonary artery tumour embolism.9 Mediastinal lymph node smaller than 10 mm may also directly invade the pulmonary artery.10 Apart from the mediastinal lymph nodes the lung mass can also directly invade into the pulmonary vessels.11 EBUS-TBNA has also been found to be useful in diagnosing pulmonary artery sarcoma12 and in diagnosing metastatic tumours from renal cell cancer13 and thyroid cancer14 to mediastinal lymph nodes.

There was no complication associated with EBUS-guided TBNA in our case. EBUS-TBNA is associated with a few complications like pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and haemomediastinum. The risk of bleeding due to the puncture of the pulmonary artery during EBUS-TBNA is usually very low. This was demonstrated by Vincent et al15 as they traversed the pulmonary artery and biopsied a left hilar mass with no significant bleeding. Other rare complications of EBUS-TBNA include mediastinal abscess,16 endobronchial polyp,17 lung abscess and pericardial effusion.18

Learning points.

Endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a novel, safe and minimally invasive procedure with a few complications.

EBUS-TBNA is useful for diagnosing mediastinal lymphadenopathy and lung parenchymal lesions along with staging of the lung cancer.

The role of EBUS-TBNA is gradually expanding to diagnose lesions in the pulmonary vessels.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Yasufuku K, Nakajima T, Motoori K, et al. Comparison of endobronchial ultrasound, positron emission tomography and CT for lymph node staging of lung cancer. Chest 2006;130:710–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams K, Shah PL, Edmonds L, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound and transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy for mediastinal staging in patients with lung cancer:systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2009;64:757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rintoul RC, Skwarski KM, Murchison JT, et al. Endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound guided real-time fine needle aspiration for mediastinal staging. Eur Respir J 2005;25:416–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Vilmann P, et al. Real time endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration for sampling mediastinal lymph nodes. Thorax 2006;61:795–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groth S, Whitson BA, D'Cunha J, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes: a single institution's learning curve. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herth F, Becker HD, Ernst A. Conventional vs endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a randomized trial. Chest 2004;125:322–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toloza EM, Harpole L, McCrory DC, Non invasive staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the current evidence. Chest 2003;123:137S–46S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Krasnik M, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes in the radiologically and PET normal mediastinum in patients with lung cancer. Chest 2008;133:887–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanc AL, Jardin C, Faivre JB, et al. Pulmonary artery tumor embolism diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Eur Respir J 2011;38:477–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto H, Watanabe K, Nagatomo A, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography for mediastinal and hilar lymph node metastases of lung cancer. Chest 2002;121:1498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacEachern P, Dang B, Stather D, et al. Tumor invasion into pulmonary vessels viewed by endobronchial ultrasound. J Bronchol 2008;15:206–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JS, Chung JH, Jheon S, et al. EBUS-TBNA in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary artery sarcoma and thromboembolism. Eur Respir J 2011;38:1480–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, Wong M, et al. Histological diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node metastases from renal cell carcinoma by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirology 2007;12:302–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow A, Oki M, Saka H, et al. Metastatic mediastinal lymph node from an unidentified primary papillary thyroid carcinoma diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Intern Med 2009;48:1293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent B, Huggins JT, Doelken P, et al. Successful real-time endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of a hilar lung mass obtained by traversing the pulmonary artery. J Thorac Oncol 2006;1:362–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moffatt-Bruce SD, Ross P. Mediastinal abscess after endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;5:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Park HY, Kim H, et al. Endobronchial inflammatory polyp as a rare complication of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010;11:340–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haas AR. Infectious complications from full extension endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration. Eur Respir J 2009;33:935–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]