Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) associated with sildenafil citrate is seen rarely in patients without any history of coronary artery disease. We report a nitrate-free patient with a history of cardiovascular risk factors who developed acute MI after taking sildenafil. A 44-year-old man diagnosed with acute anterior ST segment elevation MI 120 min after self-administration of 150 mg sildenafil was admitted before attempting any sexual intercourse. The coronary angiography revealed 99% occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and a bare-metal stent was implanted. He was discharged after 5 days without any complication. Sildenafil may cause coronary steal or may lead to vasodilation causing hypotension in patient with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, especially in patients on nitrate therapy. Our patient was nitrate free, with normal blood pressure values. Emotional stimulation associated with anticipated sexual activity may have been a triggering factor for vulnerable coronary plaque rupture.

Background

Sildenafil citrate, which is an oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE5), was the first oral drug approved for the treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED) by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Evaluation Agency.1 Although, sildenafil has no direct effect on relaxation of isolated human corpus cavernosum, it increases the effect of nitric oxide on thrombocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells by inhibiting PDE5 receptor that is responsible for degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the corpus cavernosum.2 The most commonly reported adverse effects of sildenafil are headache, gastro-oesophageal reflux, dyspepsia, facial flushing and nasal congestion.3 4 The pooled data and postmarketing surveillance analysis after the approval of sildenafil citrate by the US FDA revealed significant cardiovascular problems, including acute myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden cardiac death.5 Sildenafil-associated MI is rarely seen in patient without any history of coronary artery disease. The risk of developing MI after taking sildenafil is more common in patients with known coronary artery disease, who are on nitrate therapy which results in prolonged vasodilatation of systemic vessels leading to mild-to-severe hypotension.6 We report an asymptomatic nitrate-free patient with a history of cardiovascular risk factors including smoking and family history of coronary artery disease who developed an acute MI after taking 150 mg sildenafil citrate. It is well known that sildenafil should be used with caution in patients with existing coronary artery disease. This case underlines the equal importance of thorough evaluation of global cardiovascular risk status before the initiation of sildenafil treatment in asymptomatic ED patients.

Case presentation

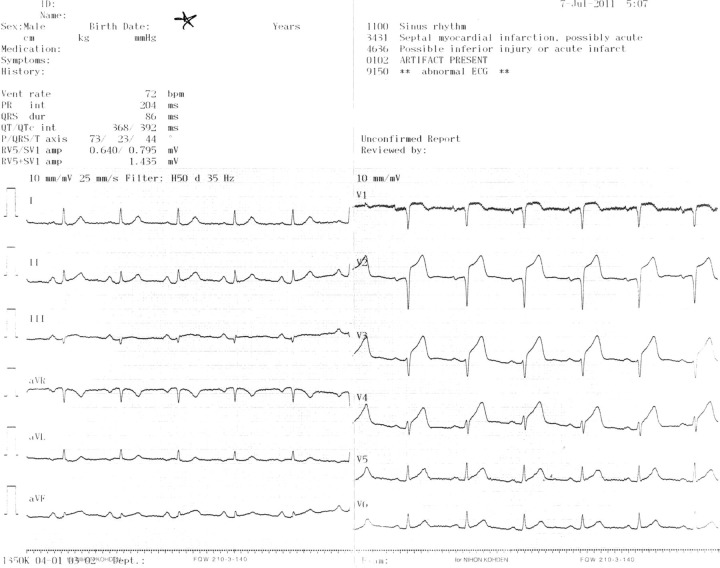

A 44-year-old man admitted to emergency department with 1 h of acute severe typical retrosternal chest pain radiating to left arm and neck, dyspnea and nausea. Symptoms had begun approximately 120 min after self-administration of 150 mg sildenafil before any attempt of sexual intercourse. He had consumed to approximately 500 ml alcohol 3 h before receiving sildenafil. His medical history revealed cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking and a family history of premature coronary artery disease. Physical examination on admission revealed a blood pressure of 160/90 mm Hg, a regular heart rate of 75 beats/min with normal auscultation findings of heart and lungs. The initial ECG showed sinus rhythm with 4 mm ST segment elevations in leads V1−V4 precordial derivations (figure 1). The laboratory measurements on admission were as follows: white cell count: 22.23×109/l, haemoglobin level 15 g/dl, platelet count 330×103/mm3, total cholesterol 171 mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol 123 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 35 mg/dl, triglyceride 108 mg/dl, serum troponin-I 12.70 ng/ml (normal range 0−0.2 ng/ml), creatine kinase 567 U/l (normal range 10−172 U/l), creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) 83 ng/ml (normal range 0−25 ng/ml). The patient was transferred to coronary care unit with diagnosis of acute anterior ST segment elevation MI.

Figure 1.

The initial ECG revealed sinus rhythm with 4 mm ST segment elevations in leads V1–V4 precordial derivations that was consistent with acute anterior MI.

Treatment

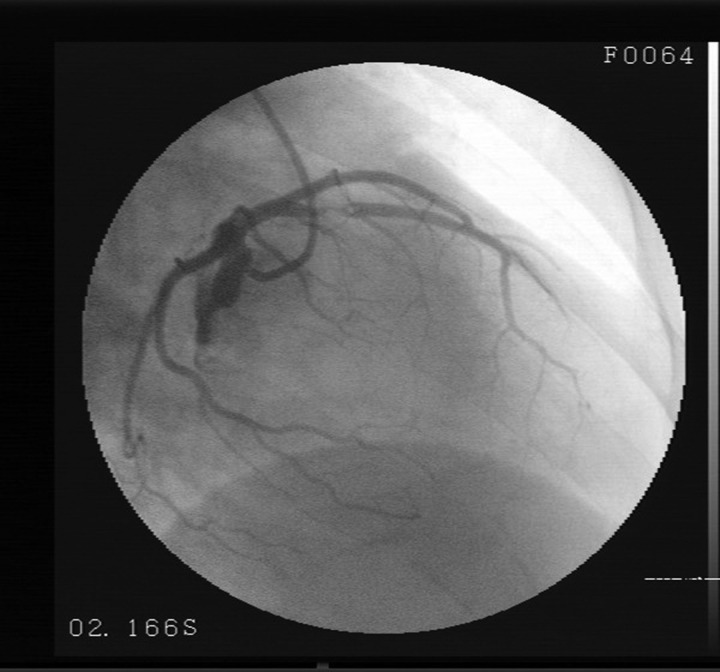

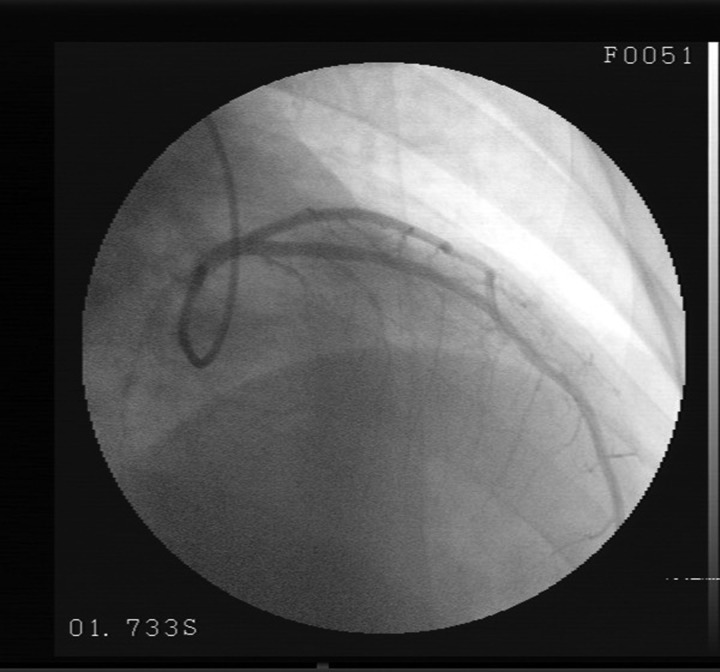

Acetylsalicylic acid 300 mg, clopidogrel 300 mg, enoxaparine 70 mg and thrombolytic therapy with alteplase (t-PA) 100 mg were given as the initial medical therapy. Since criteria for reperfusion were not met after 90 min of thrombolytic therapy and because of the presence of ongoing chest pain, rescue percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed. The coronary angiography revealed 99% occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) with normal circumflex and right coronary arteries. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTCA) and 3.5×16 mm bare metal stent implantation was performed for early coronary reperfusion for culprit LAD lesion (figures 2 and 3). TIMI-III blood flow was obtained after procedure.

Figure 2.

The coronary angiography revealed 99% occlusion of the left anterior descending artery with normal circumflex and right coronary arteries (arrows).

Figure 3.

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and 3.5×16 mm bare metal stent implantation was performed for culprit left anterior descending artery lesion.

Outcome and follow-up

The transthoracic echocardiogram at discharge showed anteroseptal and inferoapical hypokinesia with a small dyskinetic area at the apex and an ejection fraction of 40%. The patient was given acetylsalicylic acid 300 mg, clopidogrel 75 mg, metoprolol 50 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg and perindopril 10 mg daily and was discharged after 5 days without any complication.

Discussion

ED is a common and serious health concern among patients with cardiovascular disease. It has been shown that there is a significant correlation between the severity of ED and the number of vessels involved in patients with coronary artery disease.7 8 Sildenafil citrate, which is rapidly absorbed reaching maximal plasma concentrations within 1 h after oral administration and have a mean terminal half-life of 3−5 h, shows its effects on systemic and venous vascular smooth cells via cGMP-specific PDE5 inhibition.9 In our case, the patient took sildenafil tablet 2 h before clinical symptoms. Feenstra et al10 reported the first case of sildenafil associated MI in a patient with no known cardiac history, and Dakik et al11 reported a patient with sildenafil-induced acute MI with known coronary artery disease and suggested that the use of sildenafil in patients with underlying coronary artery disease might be dangerous even if the patient is asymptomatic. Although some clinical studies12 13 demonstrated that rates of MI and cardiovascular death are low and similar between men treated with sildenafil and those treated with placebo, suggesting that the use of sildenafil citrate is not associated with an increase in the risk of MI or cardiovascular death, several cardiac adverse events as malignant ventricular arrhythmias, cerebrovascular haemorrhage, transient ischaemic attack and sudden deaths were reported in patients taking sildenafil citrate by postmarketing surveillance data.5 14 It was assumed that they were related to an underlying atherosclerotic cardiac disease resulting in redistribution of arterial blood flow upon sildenafil ingestion that may cause diversion of blood from areas with already inadequate coronary perfusion—a process called coronary steal phenomenon leading to myocardial ischaemia or infarction. Sildenafil may also lead to a prolonged and exaggerated vasodilation causing hypotension in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease.14 However, our patient did not receive any nitrate and his blood pressure was normal on admission. Coronary angiography revealed no coronary lesion except for subtotal occlusion of the LAD coronary artery. It can be suggested that emotional stimulation associated with anticipated sexual activity may have been a triggering factor for vulnerable coronary plaque rupture that led to acute MI. The ACC/AHA consensus statement emphasised that patients be alerted for possible hypotension when sildenafil citrate is combined with antihypertensive drugs as calcium-channel blockers, β-blockers, diuretics and ACE inhibitors particularly in patients with congestive heart failure or chronic stable angina.15 In this case, the patient had never taken combined sildenafil and nitrate and his medical history was unremarkable for cardiovascular risk factors except for smoking and a family history of coronary artery disease. Also, some clinical studies showed small temporary relationship between absolute risk for MI and taking sildenafil presumably triggered with sexual activity even in men with ED.13 Two important studies documented that the risk for MI is approximately doubled during the 2 h period after sexual intercourse.16 17 In the present case, chest pain began shortly after taking sildenafil and before any sexual activity, thus eliminating the physical stress of sexual intercourse as the precipitating cause, which has often been implicated as a potential triggering factor in previous case reports involving sildenafil.

Several clinical studies have investigated the management of ED in patient with cardiovascular disease.5 18 According to the Princeton Consensus Panel, a large majority of patients are in the ‘low-risk’ group, which includes patients with controlled hypertension, mild stable angina, successful coronary revascularisation, prior uncomplicated MI, mild valvular disease or asymptomatic individuals with <3 cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, sildenafil could safely be given as a treatment for ED, with the exception of those who are on nitrates of any form. Patients with moderate angina, a history of recent MI within the last 6 weeks, documented left ventricular dysfunction or New York Heart Association class 2 congestive heart failure, nonsustained low-risk arrhythmias, or those with >3 CV risk factors are in ‘intermediate-risk’ group and they need further cardiac workup and restratification of their risk before starting treatment for ED. Finally, patients with unstable or refractory angina, uncontrolled hypertension, class 3 or class 4 congestive heart failure, recent MI within 2 weeks, high-risk of arrhythmias, obstructive cardiomyopathies and moderate-to-severe valvular disease are classified as ‘high-risk’ and must receive definitive treatment for their cardiac disease before resumption of sexual activity or treatment for ED.18

The sildenafil-associated MI is rarely seen in patients without any history of coronary artery disease. The association between sildenafil administration and MI may be questioned in this case; but Naranjo score, which is a questionnaire designed for determining whether an adverse drug reaction is actually due to the drug rather than the result of other factors, was 7 of 13 indicating a probable cause and effect relationship between sildenafil and acute MI in our patient.19 Yes there are some thrombi in the culprit lesion of coronary artery in coronary angiography. The presence of a small amount of thrombi in our culprit lesion may indicate that this event is not related to coronary steal phenomenon. However, the use of sildenafil combined with the physical exertion and emotional stress of sexual intercourse might be a triggering factor for coronary plaque rupture that led to acute MI in patients with asymptomatic coronary artery disease independent of nitrate intake. Although this case does not establish a definite association between sildenafil intake and development of acute MI, given its mechanism of action and the temporal relationship between ingestion of sildenafil and the onset of chest pain, the occurrence of MI in our patient was probably more than coincidental. Risk stratification guidelines, which have been developed to predict the likelihood of a significant coronary event from sexual activity or from the treatment of ED with sildenafil in men, could be a useful tool for assessing the need for further evaluation for coronary artery disease prior to initiation of PDE5 inhibitor therapy.20

Learning points.

Sildenafil should be used with caution in patients with existing coronary artery disease. It is recommended to stratify patients according to their cardiovascular risk before initiating sildenafil treatment.

Sildenafil should never be prescribed in combination with nitrates in patients without documented coronary artery disease and with no known threatening reactions of sildenafil and counsel patients not to take sildenafil before undergoing a complete physical evaluation and further testing if warranted, independent of cardiac history and nitrate use.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Chew KK, Earle CM, Stuckey BG, et al. Erectile dysfunction in general medicine practice: prevalence and clinical correlates. Int J Impot Res 2000;12:41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein I, Lue TF, Padma-Nathan Het al. Oral sildenafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Sildenafil Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;339:59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boolell M, Allen MJ, Ballard SAet al. Sildenafil: an orally active type 5 cyclic GMP–specific phos-phodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 1996;8:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahue SP, Taylor RJ. Pupil-sparing third nerve palsy associated with sildenafil citrate (Viagra). Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:476–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kloner RA. Cardiovascular risk and sildenafil. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iglesias ML, Jerico C, Skaf E, et al. Sildenafil and coronary artery disease. BJU Int 2003;92:824–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenstein A, Chen J, Miller Het al. Does severity of ischemic coronary disease correlate with erectile function? Int J Impot Res 1997;9:123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israilov S, Baniel J, Shmueli Jet al. Treatment program for erectile dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:689–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein I, Lue TF, Padma-Nathan Het al. Oral sildenafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Sildenafil Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feenstra J, van Drie-Pierik RJ, Lacle CF, et al. Acute myocardial infarction associated with sildenafil. Lancet 1998;352:957–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dakik HA, Al-Sayyed A, Sawaya JI. Viagra, sexual intercourse and acute myocardial infarction (letter). Cardiology 1999;92:220–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shakir SA, Wilton LV, Boshier A, et al. Cardiovascular events in users of sildenafil: results from first phase of prescription event monitoring in England. BMJ 2001;322:651–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittleman MA, Glasser DB, Orazem J. Clinical trials of sildenafil citrate (Viagra) demonstrate no increase in risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death compared with placebo. Int J Clin Pract 2003;57:597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manfroi WC, Caramori PR, Zago AJet al. Hemodynamic effects of sildenafil in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2003;90:153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheitlin MD, Hutter AM, Jr, Brindis RG. ACC/AHA expert consensus document: use of sildenafil (Viagra) in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:273–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller JE, Mittleman A, Maclure M, et al. Triggering myocardial infarction by sexual activity. Low absolute risk and prevention by regular physical exertion. JAMA 1996;275:1405–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moller J, Ahlbom A, Hulting Jet al. Sexual activity as a trigger of myocardial infarction. A case-crossover analysis in the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Programme (SHEEP). Heart 2001;86:387–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeBusk R, Drory Y, Goldstein I, et al. Management of sexual dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease: recommendations of the Princeton Consensus Panel. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EMet al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kekilli M, Beyazit Y, Purnak T, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after sildenafil citrate ingestion. Ann Pharmacother 2005;39:1362–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]