Abstract

Reversible phosphorylation of amino acid side chains in proteins is a frequently used mechanism in cellular signal transduction and alterations of such phosphorylation patterns are very common in cardiovascular diseases. They reflect changes in the activities of the protein kinases and phosphatases involving signaling pathways. Phosphorylation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues has been extensively investigated in vertebrates, whereas reversible histidine phosphorylation, a well-known regulatory signal in lower organisms, has been largely neglected as it has been generally assumed that histidine phosphorylation is of minor importance in vertebrates. More recently, it has become evident that the nucleoside diphosphate kinase isoform B (NDPK-B), an ubiquitously expressed enzyme involved in nucleotide metabolism, and a highly specific phosphohistidine phosphatase (PHP) form a regulatory histidine protein kinase/phosphatase system in mammals. At least three well defined substrates of NDPK-B are known: The β-subunit of heterotrimeric G-proteins (Gβ), the intermediate conductance potassium channel SK4 and the Ca2+ conducting TRP channel family member, TRPV5. In each of these proteins the phosphorylation of a specific histidine residue regulates cellular signal transduction or channel activity. This article will therefore summarize our current knowledge on protein histidine phosphorylation and highlight its relevance for cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology.

Keywords: protein histidine phosphorylation, nucleoside diphosphate kinase B, phosphohistidine phosphatase, heterotrimeric G-proteins, caveolae, SK4 channel, heart failure, atherosclerosis

Histidine Phosphorylation—Histidine Kinases and Phosphohistidine Phosphatases, a General Perspective

Phosphorylation is a most ubiquitous post-translational modification that plays an essential role in the regulation of cellular function is. In higher eukaryotes the most common forms of phosphorylation of proteins involve serine/threonine or tyrosine protein kinases and counteracting phosphatases. Both types of enzymes can be regulated by cellular signaling events.

In prokaryotes, but also in fungi and plants, phosphorylation of proteins on histidine residues is very common. The most widespread occurrence of histidine phosphorylation is in the two-component histidine kinase system. The histidine kinase is a membrane-bound sensor that on perceiving an extracellular signal undergoes autophosphorylation on a histidine residue. In the simplest two-component histidine kinase systems, this phosphoryl group is then transferred directly to an aspartate residue in a response regulator protein that catalyzes the reaction. The response regulator is often a transcription factor that is activated on phosphorylation to enhance expression of genes that provide the cellular response to the external stimulus (Attwood, 2013).

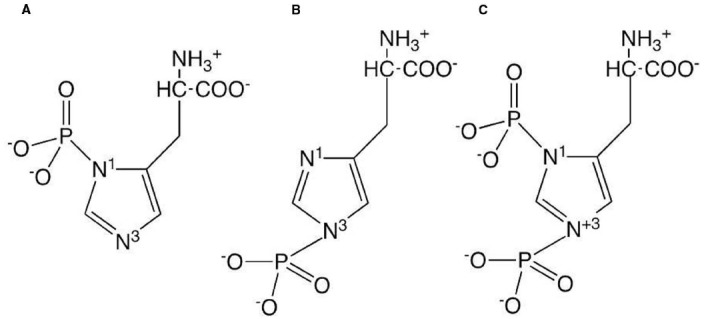

Phosphohistidine has a number of attributes that make it different from the phosphoester phosphoamino acids. The phosphoryl group is bonded to the imidazole ring of the amino acid via a phosphoramidate bond. Since the imidazole ring contains two nitrogens, there are three forms of phosphohistidine, 1- or 3-phosphohistidine or 1,3-diphosphohistidine (see Figure 1). The two forms of monophosphohistidine are both known to occur in cellular proteins (Walinder, 1969b; Chen et al., 1977; Fujitaki et al., 1981), however the diphospho form has only been reported in chemically phosphorylated proteins. Unlike the phosphoester phosphoamino acids, all forms of phosphohistidine are unstable in acidic conditions, which has made the discovery and analysis of this type of phosphorylation technically challenging and the identification of novel proteins carrying a stable phosphohistidine are rare events (Lott et al., 2006). Nevertheless, by the use of special settings in tandem mass spectrometry (Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2007) and the description of anti-phosphohistidine antibodies (Kee and Muir, 2012; Kee et al., 2013), the detection of more proteins specifically phosphorylated on histidine residues appears more likely in the future.

FIGURE 1.

Structures of the three forms of phosphohistidine: (A) 1-phosphohistidine; (B) 3-phosphohistidine; (C) 1,3-diphosphohistidine.

In prokaryotes it is now recognized that that both serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases, as well as their cognate phosphatases also occur (for reviews, see Bakal and Davies, 2000; Pereira et al., 2011; Chao et al., 2014). Although no strong evidence for the existence of two-component histidine kinase systems in higher eukaryotes has been presented sequence databases indicate the existence of proteins in higher eukaryotes that are analogous to parts of these systems (Attwood, 2013).

It has been known for more than 50 years that protein histidine phosphorylation does occur in mammalian cells (Boyer et al., 1962; Deluca et al., 1963; Peter and Boyer, 1963). Such phosphorylation was reported in a variety of tissues: liver (Smith et al., 1973; Hegde and Das, 1987; Motojima and Goto, 1994; Noiman and Shaul, 1995); brain, lung and kidney (Noiman and Shaul, 1995); platelets (Crovello et al., 1995); trachea epithelium (Muimo et al., 2000); muscle (Rose et al., 1975). Many of these proteins are enzymes that autophosphorylate an active site histidine residue to form a kinetically competent phosphoenzyme intermediate that subsequently transfers the phosphoryl group to a substrate, e.g., phosphoglycerate mutase (Rose et al., 1975), pyruvate phosphate dikinase (Spronk et al., 1976), and nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK; Walinder, 1969a). Thus many of the proteins that contain phosphohistidine are of this type and are not substrates of separate protein histidine kinases.

If histidine phosphorylation is an important post-translational modification in mammalian cell signaling, one would expect there to be phosphohistidine phosphatases. Matthews showed that some of the phosphoserine/phosphothreonine phosphatases, PP1, PP2A, and PP2C (Kim et al., 1993) are also phosphohistidine phosphatases, which utilize phosphohistidine-containing histone H4 at least as well as their phosphoserine-containing phosphoprotein substrates. These phosphatases are widely expressed in plant tissue, as well as mammalian tissue (Wong et al., 1993; Matthews and MacKintosh, 1995). More recently, a specific mammalian phosphohistidine phosphatase (PHP) has been discovered (Ek et al., 2002; Klumpp et al., 2002) and crystallized (Busam et al., 2006). This enzyme occurs in many mammalian tissues (Klumpp et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2009). It is most highly expressed in mouse brain and in human epidermal cells, but also highly expressed in mouse and human heart and skeletal muscle (Zhang et al., 2009). It dephosphorylates of all forms of phosphohistidine (Attwood et al., 2010).

Although repeatedly described as enzymatic activity (Smith et al., 1973, 1974; Chen et al., 1974, 1977; Wei and Matthews, 1991; Besant and Attwood, 2000; Tan et al., 2004) mammalian histidine kinases remained largely unidentified and are only partially characterized so far.

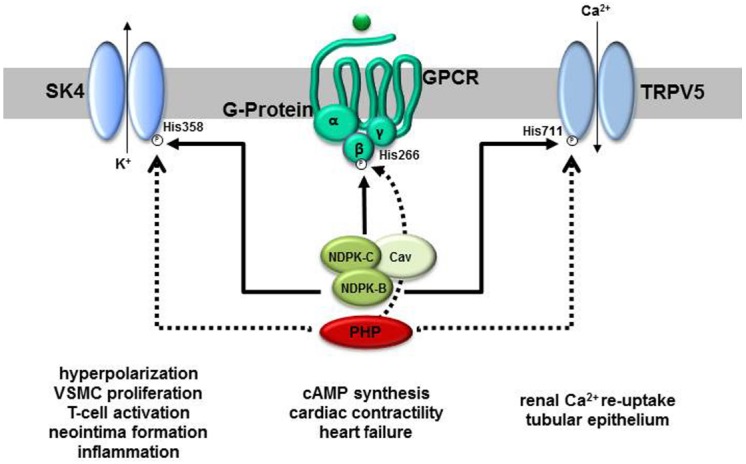

One of the first phosphoproteins to be identified that contained phosphohistidine was NDPK (Walinder, 1969a; Walinder et al., 1969). Walinder et al. (1969) showed that the phosphohistidine in NDPK was an intermediate in the phosphoryl transfer reaction between NTP and NDP catalyzed by the enzyme. More recently, it was discovered that NDPK can also act as a protein histidine kinase. NDPK-A was shown to phosphorylate a histidine residue in ATP-citrate-lyase (Wagner and Vu, 1995) whilst NDPK-B phosphorylates histidine residues in the β-subunit (Gβ) of heterotrimeric G-protein βγ-dimers (Gβγ; Cuello et al., 2003), the intermediate-conductance potassium-channel SK4 (encoded by the KCNN4 gene; Srivastava et al., 2006) and the Ca2+- conducting channel, TRPV5 (Cai et al., 2014) (Figure 2). As such, NDPKs are the best characterized mammalian histidine kinases, although little is known about the details of how they recognize their substrate proteins and catalyze the phosphoryl transfer reaction. Two of the protein substrates of NDPK-B, Gβ and SK4, play important roles in cardiovascular function and disease.

FIGURE 2.

Molecular targets of NDPK-B and PHP and their proposed functions in physiology and pathophysiology. Three proteins, the cation channels SK4 and TRPV5 as well as the β-subunit of heterotrimeric G-proteins are substrates for NDPK-B-mediated phosphorylation on defined histidine residues (His). All three phosphohistidines are also substrates to dephosphorylation by PHP. Whereas the phosphorylation of classically regulates the open-probability of the channels, the phosphorylated G-protein β-subunit takes part in a phosphorelay activating heterotrimeric G-proteins. Apparently, by a complex formation with NDPK-C and caveolins (Cav), NDPK-B additionally contributes to caveolae formation and the composition of signaling complexes, e.g., G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) containing complexes, at the plasma membrane. Whereas the channels’ activities are linked to the indicated physiological and pathophysiological events, evidence for a contribution of the phosphorelay to the regulation of cardiac cAMP formation and thus contractility has been provided.

Regulation of Cardiac Contractility by NDPK-B/βγ Complex Formation

The notion that the interaction of NDPK-B with Gβγ-dimers and the histidine phosphorylation of Gβ is involved in cAMP formation in cardiac myocytes and thus the regulation of cardiac contractility became already evident in the first reports describing this interaction. Stable cell clones of immortalized neonatal rat cardiac myocyte-derived H10 cells overexpressing NDPK-B showed an enhanced Gαs-dependent activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), which was however not seen in cells overexpressing the histidine kinase deficient NDPK mutant NDPK-B-H118N (H118) or NDPK-A (Cuello et al., 2003; Hippe et al., 2003). In membranes of these H10 cells, an increase in the content and activity of NDPK-B, as well as the formation of NDPK-B/Gβγ-complexes, was detected. This gain in functional NDPK-B/Gβγ-complexes was paralleled by an increase in intermediately phosphorylated Gβ-subunits.

Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of wild-type Gβγ-dimers, but not that of Gβγ-dimers in which the phosphorylated His266 of Gβ was mutated to leucine (GβH266Lγ), in the NDPK-B-overexpressing H10 cells further increased Gβ phosphorylation and Gαs-dependent cAMP formation (Hippe et al., 2007). GβH266Lγ, like wild-type Gβγ, was integrated into heterotrimeric G-proteins in neonatal and adult rat cardiomyocytes. However, compared to wild-type Gβγ, overexpression of GβH266Lγ suppressed basal cAMP formation, the cAMP-dependent Ser16-phosphorylation of phospholamban and contractility. A similar decrease in basal cAMP production occurred when the formation of NDPK-B/Gβγ-complexes was inhibited by siRNA-mediated NDPK-B knockdown (Hippe et al., 2007). Interestingly, in contrast to intermediately phosphorylated NDPK-B on His118, Gβ phosphorylated on His266 is a substrate for PHP and thus might be regulated also by this enzyme (Mäurer et al., 2005). Based on these data it was concluded that NDPK-B/Gβγ-complexes allow for the receptor-independent activation of G-proteins by using ATP as energy source to locally form GTP from GDP with an intermediate phosphorylation of G protein subunits at His266 (Hippe et al., 2007).

The importance of the NDPK-B/Gβγ-complex formation for cardiac contractility in zebrafish embryos has been verified by morpholino-mediated knockdown. Depletion of NDPK-B or Gβ resulted in a decrease in cardiac contractility which was associated with a reduction in the expression of the other complex partner. Moreover, the protein levels of the AC-regulating Gαs- and Gαi-subunits as well as the caveolae scaffold proteins caveolin-1 and -3 were reduced (Hippe et al., 2009). These changes were accompanied by reduced cAMP levels in the heart. Interestingly, a similar reduction of G-proteins, caveolin-1 and cAMP content was evident in embryonic fibroblasts from NDPK-A/-B double-knockout-mice. Re-expression of human NDPK-B, but not of NDPK-A, rescued this phenotype (Hippe et al., 2009). As a loss of the Gs-protein at the plasma membrane should not only affect basal but also β -adrenoceptor (βAR)-induced cAMP synthesis and cardiac contractility, the requirement of NDPK-B for basal and βAR-stimulated cAMP synthesis was further analyzed by comparing wild-type NDPK-B and its catalytically inactive H118 mutant in several cellular models, including rat cardiomyocytes. Both, re-expression of human wild-type and H118 induced the re-appearance of Gs and caveolin-1 at the plasma membrane and thus enhanced the βAR-induced cAMP formation of NDPK-B—depleted cells to a similar extent. In contrast, the catalytically inactive H118 was less potent and less effective in rescuing basal cAMP production (Hippe et al., 2011a). NDPK-B thus apparently regulates Gs function by two different mechanisms. The NDPK-B-dependent phosphorelay reaction specifically allows for a receptor-independent, basal Gαs activation and cAMP synthesis (Cuello et al., 2003; Hippe et al., 2003, 2007). The complex formation of NDPK-B with heterotrimeric Gs is additionally required for the stabilization of the Gs-protein content at the plasma membrane and thus contributes to β AR-induced cAMP formation by regulating the amount of the pivotal transducer Gs.

Regulation of Caveolae Formation by NDPK-B

Caveolae are flask-shaped invaginations in the plasma membrane which are highly enriched by scaffold proteins of the caveolin and cavin families. They take part in compartmentalization and organization of signal transduction processes. In cardiomyocytes, βARs, heterotrimeric G-proteins and AC isoforms reside in caveolae (Insel et al., 2005; Insel and Patel, 2009). As the depletion of NDPK-B was associated with a loss of the expression of the caveolin isoforms-1 and -3 as well as heterotrimeric G-proteins in zebrafish embryos (Hippe et al., 2009), an interaction of NDPK-B with caveolins and thus, involvement in caveolae formation appeared likely. Similarly, in embryonic fibroblasts from the respective knockout-mice, the membrane content of caveolin-1 and NDPK-B was found to be mutually dependent on one another and a co-immunoprecipitation of caveolin-1 and NDPK-B corroborated the direct association of the two proteins (Hippe et al., 2011b). Ultrastructural analysis revealed a reduction of surface caveolae in NDPK-B-deficient cells which was associated with a decrease in the plasma membrane bound caveolin-1. In accordance with this mutual dependence between NDPK-B and caveolin, a decrease in the plasma membrane content of NDPK-B was observed in caveolin-1-deficient cells (Hippe et al., 2011b). As these alterations could be rescued by re-expression of either NDPK-B or caveolin-1 the data indicate a disturbed transport of caveolin-1- and NDPK-B-containing protein complexes from intracellular membrane compartments to the plasma membrane if one of the components is missing. Indeed, NDPK-B has been identified as part of the coat-protein-complex-II (COPII) required for vesicle transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus (Kapetanovich et al., 2005). NDPK-B promoted the assembly of both the Sec23/24p and Sec13/31p constituents of the mammalian COPII machinery and thereby likely facilitated COPII assembly in living cells. Therefore, the authors suggested that NDPK-B is part of a scaffold-protein-complex along which ER exit sites are organized.

Caveolin-1 is also critical to other signaling cascades, e.g., the activation of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-VEGF receptor type 2 (VEGFR-2)-cascade in endothelial cells (Sonveaux et al., 2004; Chidlow et al., 2009). Therefore, a recent report demonstrating that NDPK-B is required for VEGF-induced angiogenesis and contributes to the correct localization of VEGFR-2 and VE-cadherin at the endothelial adherens junctions (Feng et al., 2014) is interesting with regard to the importance of the NDPK-B/caveolin-1 interaction. Depletion of NDPK-B in zebrafish embryos and in cultured human endothelial cells caused malformations specifically in vessels formed by angiogenesis and impaired VEGF-induced sprouting. In accordance, NDPK-B deficient mice displayed reduced angiogenic reponses in two models of pathological vessel remodeling. Indeed, a recent abstract (Gross et al., 2015) reports that NDPK-B depletion in cultured human endothelial cells strongly reduced caveolin-1 and caveolae content at the plasma membrane and thereby impaired the VEGF-induced opening of adherence junctions. Taken together, the data indicate that NDPK-B might be required in for the functionality of many processes requiring a localization of protein complexes in caveolae and is therefore of importance for cardiovascular diseases.

Alteration of Subcellular NDPK Localization and Function in Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) induces complex remodeling processes in cardiomyocytes and changes in G-protein-signaling are a hallmark in this remodeling process. Chronic sympathetic stimulation results in a desensitization of βARs including reduced expression of β1ARs and up-regulation of inhibitory G-protein-coupled receptor-kinases (GRKs; Brinks and Koch, 2010; Santulli and Iaccarino, 2013). Concomitantly, the expression and activity of the inhibitory Gi-proteins is increased by about 30% in end-stage HF (Post et al., 1999; El-Armouche et al., 2003). This is apparently associated with shift from a prevalence of Gαs-mediated AC-stimulation to Gαi-mediated inhibition (He et al., 2005). Together with the enhancement of protein phosphatase activity in HF, these alterations in cAMP signaling result in reduced phosphorylation of key cardiac Ca2+-handling proteins which are well established contributors to the reduced ventricular contractility that is characteristic of the disease (Schmidt et al., 1999).

The plasma membrane content of NDPK-A, -B, and -C are increased in patients with end-stage HF (Lutz et al., 2001, 2004). Chronic activation of βARs increases the association of these NDPKs to the sarcolemmal cardiomyocyte membrane whereas β-blocker treatment of HF patients obviously reduces the presence of NDPK at the plasma membrane (Lutz et al., 2003). It was speculated (Lutz et al., 2001), that the increase sarcolemmal NDPK content contributes to the prevalence of Gαi protein signaling and thus the well-known reduction in cAMP formation in HF. A recent abstract (Abu-Taha et al., 2013) indicates that the expression of NDPK-C in cardiomyocytes is of importance for this phenomenon. NDPK-C exhibits enzymatic activity and is able to form heterohexamers with NDPK-A and NDPK-B (Gilles et al., 1991; Erent et al., 2001). It shares 72% homology with NDPK-A and NDPK-B, but has an additional hydrophobic N-terminal domain, which can serve as a membrane anchor (Morera et al., 1995; Webb et al., 1995). It is generally less abundantly expressed than the major isoforms NDPK-A and NDPK-B (Erent et al., 2001), but it is highly enriched at the cardiac plasma membrane of patients with end-stage HF and its content in these preparations reached the levels of NDPK-A and NDPK-B (Lutz et al., 2004; Abu-Taha et al., 2013). The new data revealed that it is the only isoform out of NDPK-A, -B, and -C, the expression of which is up-regulated in human HF as well as in animal and cellular models of chronic adrenergic stimulation (Abu-Taha et al., 2013). It directly interacts with heterotrimeric G-proteins and preferentially associates with cardiac Gαi in human HF. Apparently, NDPK-C targets NDPK-heterooligomers and thus also NDPK-B to the plasma membrane and mediates the interaction with G-proteins. Future research should address whether NDPK-C is also involved in the histidine kinase activity, phosphotransfer reactions as well as the interaction with caveolins and caveolae formation.

NDPK-B-Mediated Activation of SK4 Channels in the Vasculature is Required for Neointima Formation

Three types of Ca2+-activated potassium-channels, large (BK), intermediate (SK4), and small (SK3) conductance Ca2+-activated K+-channels are expressed in the vasculature (Wei et al., 2005; Feletou, 2009; Tharp and Bowles, 2009). BK-channels are preferentially found in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). SK-channels are primarily expressed in the endothelium contributing to the control of vascular tone and blood pressure (Si et al., 2006; Kohler and Ruth, 2010). Unlike other cell types, VSMC are not terminally differentiated and respond to physiological as well as pathophysiological stimuli with alterations in their gene expression profile. During vasculoproliferative diseases, such as atherosclerosis and restenosis, VSMC cells undergo a phenotypic modulation characterized by suppression of contractile genes, increased proliferation, and migration. Interestingly, SK4 is one of those genes the expression of which is up-regulated during the phenotypic change from the contractile to the synthetic phenotype of VSMC and SK4-channels were functionally detected in proliferating VSMC (Toyama et al., 2008). In ApoE–/–-mice, a genetic model of atherosclerosis, the expression of SK4-channels was additionally increased in macrophages and T-lymphocytes that infiltrated the atherosclerotic lesions. In line with these findings, application of the selective SK4-inhibitor TRAM-34 reduced the development of atherosclerosis in these mice (Toyama et al., 2008). Also neointimal hyperplasia and stenosis after vascular injury is sensitive to TRAM-34 treatment (Kohler et al., 2003; Tharp et al., 2008) which data further suggest that the activation of SK4-channels is required for VSMC proliferation.

The activity of SK4-channels is regulated by the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Ca2+ binds sites to calmodulin that is constitutively associated with the channel C-terminus, thereby increasing channel open-probability (Xia et al., 1998; Adelman et al., 2012). As mentioned before, NDPK-B is able to phosphorylate His358 in SK4. Although it is mechanistically not clear how this phosphorylation results in the activation of the channel, its open-probability is enhanced. In addition to the phosphorylation, the presence of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate [PI(3)P] is required for full activation of the channel, although the activity of NDPK-B is not dependent on the phospholipid nor does it bind to PI(3)P (Benagiano et al., 2003). The counteracting histidine phosphatase PHP also interacts with the channel and is apparently able to form a local de-/phosphorylation teeter-totter with NDPK-B (Srivastava et al., 2006, 2008; Wieland et al., 2010). Therefore, the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of His358, the local lipid composition where the channel is inserted in the membrane as well as the Ca2+-concentration in vicinity to the channel are together fine-tuning its activity.

Recent evidence suggest that the activation of SK4 by NDPK-B in VSMC is required for neointima formation (Zhou et al., 2015) Using a mouse model of vessel remodeling, i.e., a guide-wire caused injury of one the carotid arteries; it was shown that NDPK-B-deficient mice were similarly protected from neointima formation in injured arteries as SK4-deficient mice. Patch clamp analysis in freshly isolated VSMC from the injured and non-injured vessel demonstrated the expression of SK4 only in VSMC from the in neointima of the injured vessel but not in VSMC of the quiescent, healthy vasculature. The current measurement (ISK4) indicated a constitutive activation of the SK4-channel in proliferating VSMCs of the wild-type but not of the NDPK-B-deficient mice. As this activation was completely inhibited by PHP, the phosphorylation of His358 in the de novo expressed SK4-channels by the constitutively expressed NDPK-B is pivotal to VSMC proliferation. A potential underlying mechanism is the driving of Ca2+-influx. In proliferating VSMC, TRPC channels and T-type Ca2+-channels are the main channels responsible for Ca2+-influx (House et al., 2008). In contrast to BK-channels, which are voltage-dependent, the voltage-independent SK4-channels can maintain channel opening even at strong negative membrane potentials. An increase in ISK4 due to the constitutive activation of the channel by NDPK-B will shift the membrane potential to more negative values. Such a hyperpolarization enhances the Ca2+-influx through TRPC and/or T-type Ca2+-channels. The resulting increase in the intracellular Ca2+-concentration likely triggers the activation of transcription factors and the induction of mitogenic immediate early genes (Bi et al., 2013).

Small molecules that inhibit the histidine kinase activity of NDPK-B (Buxton, 2008), interfere with its interaction with SK4 or increase PHP activity might thus offer new therapeutic options for the treatment vascular diseases such as post angioplasty restenosis. They might even be effective in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Neointima thickening in atherosclerosis does not only involve proliferation and migration of VSMC, but also activation of inflammatory cells (Libby, 2002; Niessner et al., 2006). Monocytes infiltrate the plaques, differentiate into macrophages and produce oxidative stress, proteases, and cytokines (Libby, 2002). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in plaques activate infiltrating T-lymphocytes, which in turn further stimulate macrophages (Benagiano et al., 2003; Niessner et al., 2006). The treatment of ApoE–/–-mice with the selective SK4-channel blocker TRAM-34 significantly reduced not only proliferation and migration of VSMC, but also inhibited the infiltration of plaques by inflammatory cells (Toyama et al., 2008), indicating that T-lymphocyte activation in mice also requires activation of SK4-channels. Interestingly, the SK4 channel activity was reduced by 50% also in T-cells of NDPK-B-depleted mice and this caused a strong inhibition of cytokine production. As SK4–/–-mice are protected from developing severe colitis in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease (Di et al., 2010a) and CD4-positive T-lymphocytes from NDPKB–/–- and SK4–/–-mice show similar profiles of cytokine production (Di et al., 2010a,b), it is very likely that the constitutive activation of SK4-channels is also required for inflammatory responses. Therefore, two important pathological processes in atherosclerosis, the proliferation of VSMC as well as inflammation and oxidative stress due to T-cell activation in the plaque, are likely to be targeted by such small molecules. Although such specific inhibitors are not known of today, they might be identified by screening compound libraries for example for inhibition of NDPK activity.

Conclusion

Although well known as an important regulatory event in many organisms, the role of protein histidine phosphorylation in mammals has long gone unrecognized. However, with the recent identification of NDPKs as protein histidine kinases, PHP as a specific counteracting phosphatase and the description of important substrates as Gβγ, SK4, and TRPV5, an understanding of the importance of NDPK-mediated protein histidine phosphorylation in the regulation of mammalian cell function is emerging, with the promise of much more to be discovered. As pointed out herein, two of these substrates Gβγ and SK4, both targeted by NDPK-B as protein histidine kinase, have important roles in the physiology and pathophysiology of the cardiovascular system. The apparent contribution of the NDPK-B/Gβγ- and the NDPK-B/SK4-interaction to HF and atherosclerosis, respectively, give raise to the assumption that interference with the histidine kinase activity of NDPK or even more specifically, the inhibition of the interaction of the NDPK-B with its target proteins by small molecule inhibitors might offer avenues for future treatments of cardiovascular diseases.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Wi 1373/9-3, SFB TR23, TP B6, GRK 1874 SP2), the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes, the DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research) and the BMBF (German Ministry of Education and Research). We also acknowledge the financial support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg within the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

References

- Abu-Taha H. I., Wolf N. M., Würtz C., Lutz S., El-Armouche A., Nikolaev V., et al. (2013). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase C is an essential regulator of G-protein content and cAMP production in cardiomyocytes. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 102, V1003 10.1007/s00392-013-1100-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adelman J. P., Maylie J., Sah P. (2012). Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels: form and function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 245–269. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood P. V. (2013). Histidine kinases from bacteria to humans. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41, 1023–1028. 10.1042/BST20130019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood P. V., Ludwig K., Bergander K., Besant P. G., Adina-Zada A., Krieglstein J., et al. (2010). Chemical phosphorylation of histidine-containing peptides based on the sequence of histone H4 and their dephosphorylation by protein histidine phosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 199–205. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakal C. J., Davies J. E. (2000). No longer an exclusive club: eukaryotic signalling domains in bacteria. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 32–38. 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01681-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benagiano M., Azzurri A., Ciervo A., Amedei A., Tamburini C., Ferrari M., et al. (2003). T helper type 1 lymphocytes drive inflammation in human atherosclerotic lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6658–6663. 10.1073/pnas.1135726100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besant P. G., Attwood P. V. (2000). Detection of a mammalian histone H4 kinase that has yeast histidine kinase-like enzymic activity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 32, 243–253. 10.1016/S1357-2725(99)00119-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D., Toyama K., Lemaitre V., Takai J., Fan F., Jenkins D. P., et al. (2013). The intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via controlling calcium-dependent signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 15843–15853. 10.1074/jbc.M112.427187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P. D., Deluca M., Ebner K. E., Hultquist D. E., Peter J. B. (1962). Identification of phosphohistidine in digests from a probable intermediate of oxidative phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 237, PC3306–PC3308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinks H., Koch W. J. (2010). βARKct: a therapeutic approach for improved adrenergic signaling and function in heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 3, 499–506. 10.1007/s12265-010-9206-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busam R. D., Thorsell A. G., Flores A., Hammarstrom M., Persson C., Hallberg B. M. (2006). First structure of a eukaryotic phosphohistidine phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33830–33834. 10.1074/jbc.C600231200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton I. L. (2008). Inhibition of Nm23H2 gene product (NDPK-B) by angiostatin, polyphenols and nucleoside analogs. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 51, 30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Srivastava S., Surindran S., Li Z., Skolnik E. Y. (2014). Regulation of the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV5 by reversible histidine phosphorylation mediated by NDPKB and PHPT1. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1244–1250. 10.1091/mbc.E13-04-0180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J. D., Wong D., Av-Gay Y. (2014). Microbial protein-tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 9463–9472. 10.1074/jbc.R113.520015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. C., Bruegger B. B., Kern C. W., Lin Y. C., Halpern R. M., Smith R. A. (1977). Phosphorylation of nuclear proteins in rat regenerating liver. Biochemistry 16, 4852–4855. 10.1021/bi00641a016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. C., Smith D. L., Bruegger B. B., Halpern R. M., Smith R. A. (1974). Occurrence and distribution of acid-labile histone phosphates in regenerating rat liver. Biochemistry 13, 3785–3789. 10.1021/bi00715a026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidlow J. H. Jr., Greer J. J., Anthoni C., Bernatchez P., Fernandez-Hernando C., Bruce M., et al. (2009). Endothelial caveolin-1 regulates pathologic angiogenesis in a mouse model of colitis. Gastroenterology 136, 575–584 e572. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crovello C. S., Furie B. C., Furie B. (1995). Histidine phosphorylation of P-selectin upon stimulation of human platelets: a novel pathway for activation-dependent signal transduction. Cell 82, 279–286. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90315-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello F., Schulze R. A., Heemeyer F., Meyer H. E., Lutz S., Jakobs K. H., et al. (2003). Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by a high energy phosphate transfer via nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) B and Gβ subunits. Complex formation of NDPK B with Gβγ dimers and phosphorylation of His-266 IN Gβ. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7220–7226. 10.1074/jbc.M210304200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluca M., Ebner K. E., Hultquist D. E., Kreil G., Peter J. B., Moyer R. W., et al. (1963). The isolation and identification of phosphohistidine from mitochondrial protein. Biochem. Z. 338, 512–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di L., Srivastava S., Zhdanova O., Ding Y., Li Z., Wulff H., et al. (2010a). Inhibition of the K+ channel KCa3.1 ameliorates T cell-mediated colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1541–1546. 10.1073/pnas.0910133107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di L., Srivastava S., Zhdanova O., Sun Y., Li Z., Skolnik E. Y. (2010b). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B knock-out mice have impaired activation of the K+ channel KCa3.1, resulting in defective T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38765–38771. 10.1074/jbc.M110.168070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek P., Pettersson G., Ek B., Gong F., Li J. P., Zetterqvist O. (2002). Identification and characterization of a mammalian 14-kDa phosphohistidine phosphatase. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5016–5023. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Armouche A., Zolk O., Rau T., Eschenhagen T. (2003). Inhibitory G-proteins and their role in desensitization of the adenylyl cyclase pathway in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 60, 478–487. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erent M., Gonin P., Cherfils J., Tissier P., Raschellà G., Giartosio A., et al. (2001). Structural and catalytic properties and homology modelling of the human nucleoside diphosphate kinase C, product of the DRnm23 gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 1972–1981. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.2076.doc.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feletou M. (2009). Calcium-activated potassium channels and endothelial dysfunction: therapeutic options? Br. J. Pharmacol. 156, 545–562. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00052.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Gross S., Wolf N. M., Butenschon V. M., Qiu Y., Devraj K., et al. (2014). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B regulates angiogenesis through modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2 and endothelial adherens junction proteins. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 2292–2300. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujitaki J. M., Fung G., Oh E. Y., Smith R. A. (1981). Characterization of chemical and enzymatic acid-labile phosphorylation of histone H4 using phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry 20, 3658–3664. 10.1021/bi00515a055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles A. M., Presecan E., Vonica A., Lascu I. (1991). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase from human erythrocytes. Structural characterization of the two polypeptide chains responsible for heterogeneity of the hexameric enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 8784–8789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S., Feng Y., Wolf N. M., Devraj K., Liebner S., Wieland T. (2015). NDPK B regulates angiogenesis through Caveolin-1 phosphorylation and VE-Cadherin stabilization at the membrane. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 103, P771 10.1007/s00392-014-1100-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J. Q., Balijepalli R. C., Haworth R. A., Kamp T. J. (2005). Crosstalk of β-adrenergic receptor subtypes through Gi blunts β-adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in canine heart failure. Circ. Res. 97, 566–573. 10.1161/01.RES.0000181160.31851.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde A. N., Das M. R. (1987). ras proteins enhance the phosphorylation of a 38 kDa protein (p38) in rat liver plasma membrane. FEBS Lett. 217, 74–80. 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81246-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe H. J., Abu-Taha I., Wolf N. M., Katus H. A., Wieland T. (2011a). Through scaffolding and catalytic actions nucleoside diphosphate kinase B differentially regulates basal and β-adrenoceptor-stimulated cAMP synthesis. Cell. Signal. 23, 579–585. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe H. J., Wolf N. M., Abu-Taha H. I., Lutz S., Le Lay S., Just S., et al. (2011b). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B is required for the formation of heterotrimeric G protein containing caveolae. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 384, 461–472. 10.1007/s00210-011-0618-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe H. J., Luedde M., Lutz S., Koehler H., Eschenhagen T., Frey N., et al. (2007). Regulation of cardiac cAMP synthesis and contractility by nucleoside diphosphate kinase B/G protein βγ dimer complexes. Circ. Res. 100, 1191–1199. 10.1161/01.RES.0000264058.28808.cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe H. J., Lutz S., Cuello F., Knorr K., Vogt A., Jakobs K., et al. (2003). Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by a high energy phosphate transfer via nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) B and Gβ subunits. Specific activation of Gsα by an NDPK B.Gβγ complex in H10 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7227–7233. 10.1074/jbc.M210305200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippe H. J., Wolf N. M., Abu-Taha I., Mehringer R., Just S., Lutz S., et al. (2009). The interaction of nucleoside diphosphate kinase B with Gβγ dimers controls heterotrimeric G protein function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16269–16274. 10.1073/pnas.0901679106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House S. J., Potier M., Bisaillon J., Singer H. A., Trebak M. (2008). The non-excitable smooth muscle: calcium signaling and phenotypic switching during vascular disease. Pflugers. Arch. 456, 769–785. 10.1007/s00424-008-0491-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel P. A., Head B. P., Ostrom R. S., Patel H. H., Swaney J. S., Tang C. M., et al. (2005). Caveolae and lipid rafts: G protein-coupled receptor signaling microdomains in cardiac myocytes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1047, 166–172. 10.1196/annals.1341.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel P. A., Patel H. H. (2009). Membrane rafts and caveolae in cardiovascular signaling. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens 18, 50–56. 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283186f82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovich L., Baughman C., Lee T. H. (2005). Nm23H2 facilitates coat protein complex II assembly and endoplasmic reticulum export in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 835–848. 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee J. M., Muir T. W. (2012). Chasing phosphohistidine, an elusive sibling in the phosphoamino acid family. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 44–51. 10.1021/cb200445w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee J. M., Oslund R. C., Perlman D. H., Muir T. W. (2013). A pan-specific antibody for direct detection of protein histidine phosphorylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 416–421. 10.1038/nchembio.1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Huang J., Cohen P., Matthews H. R. (1993). Protein phosphatases 1, 2A, and 2C are protein histidine phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18513–18518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinnijenhuis A. J., Kjeldsen F., Kallipolitis B., Haselmann K. F., Jensen O. N. (2007). Analysis of histidine phosphorylation using tandem MS and ion-electron reactions. Anal. Chem. 79, 7450–7456. 10.1021/ac0707838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp S., Hermesmeier J., Selke D., Baumeister R., Kellner R., Krieglstein J. (2002). Protein histidine phosphatase: a novel enzyme with potency for neuronal signaling. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 22, 1420–1424. 10.1097/00004647-200212000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler R., Ruth P. (2010). Endothelial dysfunction and blood pressure alterations in K+-channel transgenic mice. Pflugers. Arch. 459, 969–976. 10.1007/s00424-010-0819-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler R., Wulff H., Eichler I., Kneifel M., Neumann D., Knorr A., et al. (2003). Blockade of the intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel as a new therapeutic strategy for restenosis. Circulation 108, 1119–1125. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086464.04719.DD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. (2002). Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 420, 868–874. 10.1038/nature01323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott J. S., Paget B., Johnston J. M., Delbaere L. T., Sigrell-Simon J. A., Banfield M. J., et al. (2006). The structure of an ancient conserved domain establishes a structural basis for stable histidine phosphorylation and identifies a new family of adenosine-specific kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22131–22141. 10.1074/jbc.M603062200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S., Hippe H. J., Niroomand F., Wieland T. (2004). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Methods Enzymol. 390, 403–418. 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S., Mura R., Baltus D., Movsesian M., Kubler W., Niroomand F. (2001). Increased activity of membrane-associated nucleoside diphosphate kinase and inhibition of cAMP synthesis in failing human myocardium. Cardiovasc. Res. 49, 48–55. 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S., Mura R., Hippe H., Tiefenbacher C., Niroomand F. (2003). Plasma membrane-associated nucleoside diphosphate kinase (nm23) in the heart is regulated by β-adrenergic signaling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140, 1019–1026. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H. R., MacKintosh C. (1995). Protein histidine phosphatase activity in rat liver and spinach leaves. FEBS Lett. 364, 51–54. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00353-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäurer A., Wieland T., Meissl F., Niroomand F., Mehringer R., Krieglstein J., et al. (2005). The β-subunit of G proteins is a substrate of protein histidine phosphatase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334, 1115–1120. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morera S., Lacombe M.-L., Yingwu X., Lebras G., Janin J. (1995). X-ray structure of human nucleoside diphosphate kinase B complexed with GDP and 2A resolution. Structure 3, 1307–1314. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motojima K., Goto S. (1994). Histidyl phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of P36 in rat liver extract. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 9030–9037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muimo R., Hornickova Z., Riemen C. E., Gerke V., Matthews H., Mehta A. (2000). Histidine phosphorylation of annexin I in airway epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36632–36636. 10.1074/jbc.M000829200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessner A., Sato K., Chaikof E. L., Colmegna I., Goronzy J. J., Weyand C. M. (2006). Pathogen-sensing plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulate cytotoxic T-cell function in the atherosclerotic plaque through interferon-α. Circulation 114, 2482–2489. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noiman S., Shaul Y. (1995). Detection of histidine-phospho-proteins in animal tissues. FEBS Lett. 364, 63–66. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00358-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S. F., Goss L., Dworkin J. (2011). Eukaryote-like serine/threonine kinases and phosphatases in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 192–212. 10.1128/MMBR.00042-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter J. B., Boyer P. D. (1963). The formation of bound phosphohistidine from adenosine triphosphate-P32 in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 1180–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post S. R., Hammond H. K., Insel P. A. (1999). β-Adrenergic receptors and receptor signaling in heart failure. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 39, 343–360. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose Z. B., Hamasaki N., Dube S. (1975). The sequence of a peptide containing the active site phosphohistidine residue of phosphoglycerate mutase from chicken breast muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 7939–7942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli G., Iaccarino G. (2013). Pinpointing beta adrenergic receptor in ageing pathophysiology: victim or executioner? Evidence from crime scenes. Immun. Ageing 10, 10. 10.1186/1742-4933-10-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U., Hajjar R. J., Kim C. S., Lebeche D., Doye A. A., Gwathmey J. K. (1999). Human heart failure: cAMP stimulation of SR Ca2+-ATPase activity and phosphorylation level of phospholamban. Am. J. Physiol. 277, H474–H480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si H., Heyken W. T., Wolfle S. E., Tysiac M., Schubert R., Grgic I., et al. (2006). Impaired endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated dilations and increased blood pressure in mice deficient of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Circ. Res. 99, 537–544. 10.1161/01.RES.0000238377.08219.0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. L., Bruegger B. B., Halpern R. M., Smith R. A. (1973). New histone kinases in nuclei of rat tissues. Nature 246, 103–104. 10.1038/246103a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. L., Chen C. C., Bruegger B. B., Holtz S. L., Halpern R. M., Smith R. A. (1974). Characterization of protein kinases forming acid-labile histone phosphates in Walker-256 carcinosarcoma cell nuclei. Biochemistry 13, 3780–3785. 10.1021/bi00715a025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonveaux P., Martinive P., Dewever J., Batova Z., Daneau G., Pelat M., et al. (2004). Caveolin-1 expression is critical for vascular endothelial growth factor-induced ischemic hindlimb collateralization and nitric oxide-mediated angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 95, 154–161. 10.1161/01.RES.0000136344.27825.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spronk A. M., Yoshida H., Wood H. G. (1976). Isolation of 3-phosphohistidine from phosphorylated pyruvate, phosphate dikinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 73, 4415–4419. 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S., Li Z., Ko K., Choudhury P., Albaqumi M., Johnson A. K., et al. (2006). Histidine phosphorylation of the potassium channel KCa3.1 by nucleoside diphosphate kinase B is required for activation of KCa3.1 and CD4 T cells. Mol. Cell 24, 665–675. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S., Zhdanova O., Di L., Li Z., Albaqumi M., Wulff H., et al. (2008). Protein histidine phosphatase 1 negatively regulates CD4 T cells by inhibiting the K+ channel KCa3.1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14442–14446. 10.1073/pnas.0803678105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E., Besant P. G., Zu X. L., Turck C. W., Bogoyevitch M. A., Lim S. G., et al. (2004). Histone H4 histidine kinase displays the expression pattern of a liver oncodevelopmental marker. Carcinogenesis 25, 2083–2088. 10.1093/carcin/bgh222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp D. L., Bowles D. K. (2009). The intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (KCa3.1) in vascular disease. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 7, 1–11. 10.2174/187152509787047649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp D. L., Wamhoff B. R., Wulff H., Raman G., Cheong A., Bowles D. K. (2008). Local delivery of the KCa3.1 blocker, TRAM-34, prevents acute angioplasty-induced coronary smooth muscle phenotypic modulation and limits stenosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1084–1089. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama K., Wulff H., Chandy K. G., Azam P., Raman G., Saito T., et al. (2008). The intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 contributes to atherogenesis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3025–3037. 10.1172/JCI30836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P. D., Vu N. D. (1995). Phosphorylation of ATP-citrate lyase by nucleoside diphosphate kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21758–21764. 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walinder O. (1969a). Evidence of the presence of 1-phosphohistidine as the main phosphohistidine as the main phosphorylated component at the active site of bovine liver nucleoside diphosphate kinase. Acta Chem. Scand. 23, 339–341. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.23-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walinder O. (1969b). Protein-bound acid-labile phosphate. Isolation of 1-32P-phosphohistidine and 3-32P-phosphohistidine from some mammalian and microbial cell extracts incubated with adenosine triphosphate-32P. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 1065–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walinder O., Zetterqvist O., Engstrom L. (1969). Intermediary phosphorylation of bovine liver nucleoside diphosphate kinase. Studies with a rapid mixing technique. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 1060–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb P., Perisic O., Mendola C., Backer J., Williams R. (1995). The crystal structure of a human nucleoside diphosphate kinase, NM23-H2. J. Mol. Biol. 251, 574–587. 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei A. D., Gutman G. A., Aldrich R., Chandy K. G., Grissmer S., Wulff H. (2005). International Union of Pharmacology. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 463–472. 10.1124/pr.57.4.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. F., Matthews H. R. (1991). Identification of phosphohistidine in proteins and purification of protein-histidine kinases. Methods Enzymol. 200, 388–414. 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00156-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland T., Hippe H. J., Ludwig K., Zhou X. B., Korth M., Klumpp S. (2010). Reversible histidine phosphorylation in mammalian cells: a teeter-totter formed by nucleoside diphosphate kinase and protein histidine phosphatase 1. Methods Enzymol. 471, 379–402. 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)71020-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C., Faiola B., Wu W., Kennelly P. J. (1993). Phosphohistidine and phospholysine phosphatase activities in the rat: potential protein-lysine and protein-histidine phosphatases? Biochem. J. 296(Pt 2), 293–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. M., Fakler B., Rivard A., Wayman G., Johnson-Pais T., Keen J. E., et al. (1998). Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 395, 503–507. 10.1038/26758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Q., Sundh U. B., Jansson L., Zetterqvist O., Ek P. (2009). Immunohistochemical localization of phosphohistidine phosphatase PHPT1 in mouse and human tissues. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 114, 65–72. 10.1080/03009730802642337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. B., Feng Y. X., Sun Q., Lukowski R., Qiu Y., Spiger K., et al. (2015). Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B-activated intermediate conductance potassium channels are critical for neointima formation in mouse carotid arteries. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 1852–1861. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]