Abstract

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is a well-characterised antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA)-positive vasculitis in cocaine abuser patients. However, due to the short half-life of levamisole in serum and urine, the causal role of levamisole is not established. Here we report the detection of both levamisole and cocaine in hair samples of a patient who presented with an ANCA-positive vasculitis. The higher concentration of levamisole in proximal sample of the hair confirms that the patient abused of cocaine added with levamisole in the days preceding the development of skin lesions. Although a direct causative role has not been established, our report strongly suggests that levamisole may have triggered vasculitis in this case.

Background

I think that our case (clinical presentation) and the way we demonstrated the potential link between levamisole and vasculitis is quite original and may interest a wild range of physicians as this clinical picture may be more frequent than we think and the test is easy to perform.

Introduction

Levamisole is a well-known antihelmintic agent and immunomodulator. Cases of vasculitis induced by levamisole have been reporting in the setting of cocaine abuse as levamisole is used as an additive. In this report, we describe the interest of an original new test to confirm the short-term and long-term exposition to levamisole when suspecting its role in the pathogenesis of vasculitis.

Case report

In May 2011, a 39-year-old Caucasian woman, who had a history of occasional cocaine consumption, presented with painful reticular erythematous skin lesions associated with fever, rhinitis and polyarthralgia. During the last 10 years, she has been explored several times for a recurrent biopsy-proven septal panniculitis, concomitant with rhinitis, fever and arthralgia (six to eight stereotypic episodes per year). Throat swab and antistreptolysin O antibodies were positive, consistent with chronic Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in agreement with the diagnosis of poststreptococcal Erythema nodosum. As a result, she received penicillin V (Oracillin) without efficacy. During the follow-up, she developed new nodular and inflammatory lesions mainly on the lower limbs but the biological explorations remained negative excepted the detection, in May 2010, of antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA) at a titre of 1/640 with myeloperoxydase (MPO) specificity at 77 U/ml (Elisa; Euroimmun).

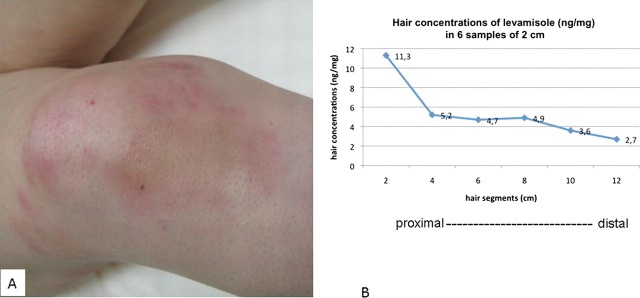

Upon physical examination, she had newly reddish reticular hyperalgic knee lesions (figure 1A). Skin biopsy specimen showed hypodermitis with mild signs of leucocytoclastic vasculitis without fibrinoid necrosis but with rough shape of interstitial granuloma. The ear–nose–throat (ENT) examination showed nasal septum perforation but ENT surgical biopsy showed no sign of granuloma or vasculitis. Blood count was normal, partial thromboplastin time test was increased but not consistent with lupus anticoagulant. ANCA were positive at 1/1280 with anti-MPO antibodies at 126 U/ml (Elisa; Euroimmun). Anticardiolipin and anti-β2 GP1 antibodies were negative. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg per day) and mehotrexate (20 mg per week) were initiated. Adherence to treatment was poor and persistent cocaine consumption was suspected, although denied by the patient, which led us to raise the hypothesis of levamisole-induced vasculitis.

Figure 1.

(A) Reddish reticular and infiltrated lesions of the knee. (B) Determination of levamisole in different sections of the hair (using ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry after sample pretreatment) showing a higher concentration in proximal segment, suggestive of a recent consumption of cocaine adulterant levamisole.

Investigations

A 12-cm hair sample was collected in order to measure concentrations of levamisole and cocaine. Since hair growth is approximately 1 cm per month, this was consistent with retrospective analysis of annual levamisole exposition. After pretreatment (hair-crushing and liquid–liquid extraction), the sample was positive for both levamisole and cocaine in the slightly modified previously published methods (UPLC-MS/MS and FPIA-AXSYM Abbott, respectively)1 2 with a concentration of benzoylecgonine of 33 ng/mg with highest rates during the last 2 months. Moreover, concentration of levamisole was higher in the proximal segment (11.3 ng/mg) than in others (figure 1B), suggesting recent cocaine intake. Levamisole was measured in a control hair segment of a non-exposed individual and was lower than the limit of quantification (LOQ=0.05 ng/mg).

Outcome and follow-up

We finally made the diagnosis of levamisole-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis related to cocaine abuse. Clinical improvement was noticed as immunosuppressive therapy was resumed.

Discussion

Levamisole was first used as an antihelmintic agent and as an immunomodulatory molecule. It has become a very prominent additive to cocaine that enhances its euphoric effects. First description by Scheinberg et al3 of cutaneous necrotising vasculitis induced by levamisole was in 1977 in a patient with breast cancer. During the 1990s, levamisole-related vasculitis typically localised in the ear lobe was described in children treated for nephrotic syndrome. It was only in 2003 that levamisole was first identified as a cocaine adulterant and thus was supposed to be related to skin involvement, although it is believed that some of the clinical manifestation may be also due to cocaine and not levamisole alone. The typical clinical picture was a necrotising vasculitis or a ‘retiform purpura’ of the extremities associated in 93% of the 16 previous reported cases with ANCA.4 Since serum and urine levamisole detection is difficult due to its short half-life (5.6 h in humans)5 and its relatively low concentration in illicit cocaine powder (1.5–4.6%),6 the causal link between levamisole and clinical findings is not proven.

While the best treatment for this condition is still unknown, some authors have reported that patients have responded to stopping the inciting drug that illustrates its causative link.

Our observation suggests that levamisole hair detection could be interesting in this setting especially when the clinical presentation is somewhere atypical as it was the case in our observation.

Learning points.

Think about levamisole intake in a patient who had cocaine abused and presented with skin vasculitis.

Detection of levamisole and cocaine in the hair reflect short-term and long-term intake.

Acknowledgments

To Dr Ludivine Gressier and Pr Luc Mouthon for helping in the management of the patient. To EveCourbon for helping in the pharmacological experiments.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Lynch KL, Dominy SS, Graf J, et al. Detection of levamisole exposure in cocaine users by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol 2011;35:176–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kintz P, Ludes B, Mangin P. Detection of drugs in human hair using Abbott ADx, with confirmation by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). J Forensic Sci 1992;37:328–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheinberg MA, Bezerra JB, Almeida FA, et al. Cutaneous necrotising vasculitis induced by levamisole. Br Med J 1978;1:408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaïne. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:1385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woestenborghs R, Michielsen L, Heykants J. Determination of levamisole in plasma and animal tissues by gas chromatography with thermionic specific detection. J Chromatogr 1981;224:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider S, Meys F. Analysis of illicit cocaine and heroin samples seized in Luxembourg from 2005–2010. Forensic Sci Int 2011;212:242–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]