Abstract

We report the case of a 70-year-old woman who developed life-threatening arrhythmia as a result of acute and severe hypokalaemia, which she developed after consuming large quantities of a liquorice-rich herb tea. She had no previous heart condition. We also discuss the legislative discrepancy in both the USA and in Europe, whereby consumers are warned about the risk of chronic hypertension whenever they buy a product containing liquorice, yet the risk of hypokalaemia may not be mentioned at all.

Background

As far as we are aware, this case is the first reported that illustrates the danger of the acute ingestion of liquorice in the absence of a previous heart condition. We believe that the acceptable daily intake should be shown on commercial products, especially herbal teas, which people drink ad libitum.

Case presentation

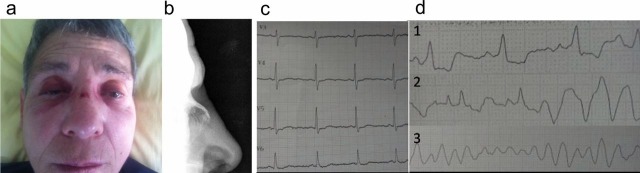

A 70-year-old woman, with a familial history of colorectal cancer, but no personal medical history, was scheduled for an outpatient colonoscopy as a primary screening test. A preoperative assessment 2 weeks before anaesthesia found her blood potassium to be 4.8 mmol/l. She was then asked to avoid heavy solid foods and to increase her fluid intake. She started to drink large volumes of a liquorice-rich herbal tea (∼15 bags/day). Colonoscopy did not reveal any lesion. She was discharged. While she was waiting for the train, she suddenly fell over without any warning, and sustained a peri-orbital haematoma and a nasal fracture (figure 1). Her blood potassium was 2 mmol/l and her kaliuresis 89 mmol/l, confirming that the hypokalaemia was of renal origin.

Figure 1.

(A) Facial trauma with (B) nose fracture upon admission; (C) initial ECG showing flattened T-waves and (D) cardiac monitoring revealing sudden ventricular arrhythmia during the correction phase of hypokalaemia.

Investigations

The ECG showed flattened T waves and a U wave. A retrospective high-performance liquid chromatography analysis found 10 mg/l of glycyrrhizin in a spot urinary sample taken on the day she was admitted (vs 53 mg/l in the herbal tea). Some time later, an echocardiography and a Holter monitor did not reveal any predisposing heart condition, and a thorough exploration of her renin/aldosterone axis was normal.

Treatment

Cardiac monitoring was started, and a catheter inserted into the right femoral vein to allow the safe (13 mmol/h) administration of potassium.

Outcome and follow-up

During the correction phase, ventricular arrhythmia recurred, and required defibrillation. She required a total of 0.84 mole of potassium to recover a stable and normal kalaemia. She was discharged and is now well and living at home.

Discussion

Liquorice is the root of a legume, Glycyrrhiza glabra, which has been used worldwide for thousands of years in food preparations such as candies or teas. The main flavour of liquorice is anethole, a distinctive aromatic compound shared by few other plants. The peculiarity of liquorice, however, is that it is sweetened by glycyrrhizin, an odourless sugar. Incidentally, glycyrrhizin is also a potent inhibitor of the 11β hydroxy-steroid dehydrogenase (11βHSD), an enzyme that converts cortisol into cortisone, and thereby prevents endogenous cortisol from binding to the mineralocorticoid receptor.1 In the principal cells of cortical collecting duct, the presence of 11βHSD allows aldosterone to activate this receptor in an uncompetitive manner (cortisol is present at 100-fold higher concentrations in the circulation).

Thus, glycyrrhizin leads to sodium reabsorption, which in turn generates a negative electric potential in the tubular lumen that drives the excretion of potassium ions. Although hypertension is usually seen as the main adverse effect of liquorice abuse, hypokalaemia is the most dangerous complication in the short term. In 1974 the USA Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) issued an opinion report stating that liquorice was a GRAS (generally recognised as safe) compound.2 Despite this, the FDA website still advises consumers, ‘regardless of their age or health status, to avoid consuming large amounts of black liquorice in concentrated time periods’.3 In 2003, the European Scientific Committee of Food (SCF) also issued an opinion report stating that the consumption of 100 mg of liquorice per day could present a dietary hazard.4 In 2008, a legislative act of the European Union demanded that label information be implemented to (1) mention the presence of liquorice in every commercially available preparation and (2) advise people with hypertension against ingesting excessive amounts.5 However, just how much liquorice corresponds to ‘large amounts’ (FDA) or is considered as ‘excessive’ (SCF)? This is not unexplained to consumers (and the risk of hypokalaemia is not even mentioned).

Learning points.

Ingestion of large amounts of liquorice is not only a source of hypertension but can also cause life-threatening hypokalaemia.

It can occur in the absence of any existing heart condition, or of diuretic intake.

The US and European legislation should improve and clarify the acceptable daily intake in the labelling of commercial products.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Stewart PM, Wallace AM, Valentino R, et al. Mineralocorticoid activity of licorice: 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency comes of age. Lancet 1987;2:821–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Database, report#28, ID code 1405-86-3, US food and Drug Administration, 1974.

- 3. Black licorice: trick or treat? Consumer Health Information. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/UCM277166.pdf (accessed October 2011).

- 4.Scientific Committee of Food, European Commission, Health and Consumer Protection Directorate General, 10 April 2003.

- 5.Official Journal of the European Union, Commission directive 2008/5/5EC. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:027:0012:0016:EN:PDF