Abstract

A young mother presented her 19-month-old boy to the general practitioner (GP) with a 24 h history of reluctance to stand or walk and a slightly raised temperature. The GP arranged an assessment by the paediatrician, who organised an ultrasound of the hips which was normal. Approximately 1 week later the patient became constipated as well, was seen again by another GP but no cause was found. Another week later mother consulted the initial GP again as the boy had not shown any signs of improvement and had become more irritable. The GP arranged a review by the paediatrician and MRI scans of the hips and back were performed. These scans showed normal hips but lumbar spine changes suggestive of a spondylodiscitic event. The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics, a corset and analgesia and made an excellent recovery.

Background

Spondylodiscitis is an inflammatory disease, usually infectious, of one or more vertebral bodies and of the corresponding intervertebral discs.1 In children the diagnosis can be a major challenge due to some of the following reasons. First, paediatric spondylodiscitis is uncommon to rare.2–4 Second, a child's signs and symptoms are often subtle and unspecific, for example abdominal pain, fever or refusal to walk. Third, it is difficult to obtain adequate information from a young, distressed and uncooperative child. Further, laboratory investigations are often unhelpful and blood cultures are usually negative.3 4 Finally x-rays of the spine are completely normal in early spondylodiscitis.4

This case report is written to illustrate this paediatric diagnostic challenge from a general practitioner (GP) and hospital specialist point of view and with the aim to avoid delay in diagnosis in similar cases.

Of note is that the patient presented in this case report was treated in a German hospital. As such the approach to management and treatment may be somewhat different from care that would have been provided in the UK healthcare system.

Case presentation

This case is about a 19-month-old Caucasian boy who lives in Germany. Regarding the medical history it may be of note that in Summer 2011 the boy was admitted to hospital for temperature symptoms. He was thought to suffer from a bacterial infection, although no specific focus was found, was treated with antibiotics and made a full recovery. In November 2011 he had hand, foot and mouth disease which cleared up spontaneously, and early December 2011 he had a short spell of diarrhoea and vomiting which resolved quickly and without obvious repercussions. Otherwise the patient is perfectly healthy, fully immunocompetent and there is no significant social or family history.

In the morning of the 22 December 2011 a young mother presented this 19-month-old son to the GP. Starting the previous day mother had noticed that the boy appeared reluctant to stand or walk. When he was encouraged to walk he had a limp which seemed to be related to his right leg. Also she had noticed that he had a slightly raised temperature, yet otherwise was not unwell. There was no indication for a trauma. The GP noticed the reluctance of the patient to walk, yet otherwise the patient was not unwell, he had a temperature of 37.5°C and on clinical examination no major abnormalities could be detected. Even so, the GP arranged for the patient to be seen that same day by the hospital consultant for an opinion and further investigations if required.

In the hospital the paediatrician considered a ‘coxitis fugax’ (irritable hip), arranged an ultrasound of the hips (and knees) which did not show any pathology. Mother was advised to seek further advice if the symptoms persisted.

Over the Christmas period the family went to the UK and visited a GP twice. The patient's reluctance to walk had not improved and mother had noticed that her son had become constipated. The British GP thought it could be a ‘hip cold’ and no further action was recommended at that moment in time.

Early January 2012, back in Germany, mother brought the patient back to the original GP for a review. Mother felt worried about her son and thought that he had not improved at all despite the use of analgesia. She explained that the patient cried and screamed a lot, that he still refused to walk and still had a temperature on and off. The GP performed an extensive clinical examination, yet could not find any specific abnormalities, especially back, hips and knees did not indicate pathology. Notwithstanding, the GP insisted on a further opinion from his hospital colleagues and the patient was seen that day.

The paediatrician could not find any major abnormalities on clinical examination either, the boy's temperature was 37.6°C. He arranged for the patient to undergo further investigations.

Investigations

At this stage hip pathology was still suspected and therefore the diagnostic process was focused on the hip joints. The previous ultrasound of the hips had not shown effusion or other pathology, hence that an MRI scan was planned with the aim to rule out epiphysiolysis, a periarticular inflammation, etc. On 9 January 2012 the patient was admitted for an MRI scan of the hips. This MRI did not show hip pathology, yet suggested abnormalities at the edge of the scan in the lower back area. Subsequently in the same session the radiologist obtained an additional sequence of pictures focusing on the lumbar column. The report indicated structural change of the entire the L5/S1 intervertebral disc with slight reduction in height and prolapse towards dorsal, no prolapsed mass, no spinal stenosis and signal changes of the basal and deck plates with an entrapment like situation of the right S1 nerve root. This was suggestive of an inflammatory spondylodiscitic event.

As a result the patient was kept in hospital and a wide range of tests was performed. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was found to be 115 mm after the first hour (Westergren method). Haemoglobin was 10.1 g/dl (10.8–12.8 g/dl), mean cell volume 65.4 fl (73–101 fl), medium cell haemoglobin 20.6 pg (23–31 pg). All other routine blood tests, including white blood cell count, platelets, liver function, urea and electrolytes (U+Es), glucose, C reactive protein (CRP) were all normal. Serum tests for campylobacter, salmonella, yersinia and listeria antibodies and for brucellosis were all negative. Blood cultures were sterile. Testing for tuberculosis was negative.

Ultrasound of the abdomen was reported as normal.

The patient underwent a lumbar puncture with the aim to culture the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). However, the culture was sterile and did not show any evidence of a pathogen.

An x-ray of the lumbar spine did not show pathology.

A bone scintigram showed a marginal inhomogeneous enhancement at level L5/S1 only, otherwise the entire vertebral column was reported as normal. However, there was an increased uptake at the level of the left distal tibia. A subsequent MRI scan focusing on this part of the left tibia did not indicate specific pathology. A specific orthopaedic consultation and clinical examination did not indicate pathology nor did it provide further information, especially no pain on percussion or palpation of the spine could be detected.

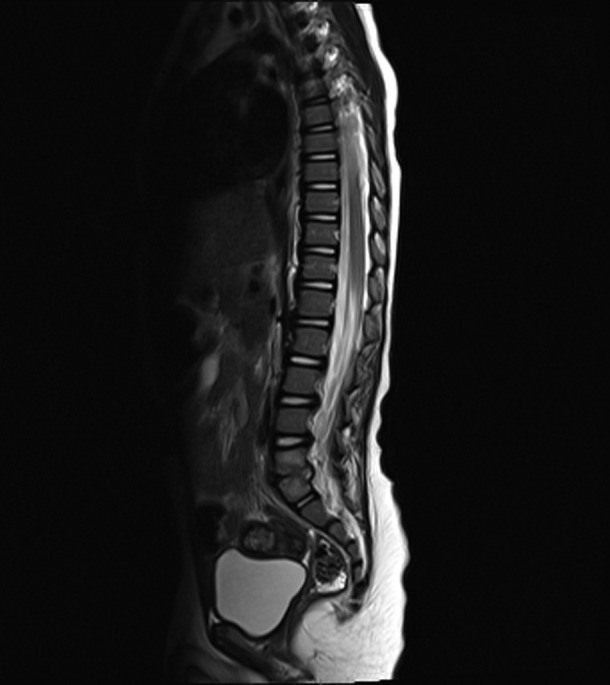

Based on the above investigations and intradisciplinary and extradisciplinary discussions a diagnosis of spondylodiscitis was set. The affected area was thought to involve the vertebral disc but also significant parts of the adjacent vertebrae, to be of an infective origin and to require intensive use of antibiotics (figure 1).

Figure 1.

T2-weighted sagittal MRI scan of the spine at date of diagnosis (9 January 2012), showing damage of disc L5/S1 and of the adjacent vertebrae.

Differential diagnosis

A toddler that declines to walk can be a diagnostic conundrum.

In theory a leg or back trauma could be considered in the differential diagnosis, yet in this case there was no indication of any injury.

The diagnosis of coxitis fugax (irritable hip) was high up in the differential diagnosis as it is a common cause, yet dismissed once ultrasound of the hips was reported as normal. An MRI scan of the hips excluded further hip pathology.

The lumbar pathology which was detected on the MRI scan was initially difficult to classify. Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis and spondylodicitis were all in the differential diagnosis, yet based on expertise from various German centres the diagnosis of a spondylodiscitis of an infective origin was set. Various tests were performed yet failed to identify the causative microorganism. The sterile CSF excluded meningitis. There were no indications for an infection outside of the spinal area.

Finally a malignant process was shortly thought of based on the initial abnormalities on the scintigram of the left tibia, yet rejected as the subsequent MRI did not show pathology.

Treatment

The patient was admitted on 9 January 2012. Intra and inter disciplinary discussions were used to decide on the best treatment. Initially the patient was started on regular intravenous clindamycin at a dose of 160 mg three times a day (40 mg/kg/day). This was given in total for 4 weeks (until the day of hospital discharge).

A back brace (corset) was fitted to support the spine and to reduce mobility.

Pain relief at admission consisted of regular oral Ibuprofen (juice) 100 mg (=8.5 mg/kg/dose) twice a day. For pains in the evening the patient was given additional metamizol 250 mg (drops) once, occasionally he received additional paracetamol 150 mg (juice, 12.8 mg/kg/dose). From 20 January 2012 the pain was controlled with regular ibuprofen 100 mg three times a day and no further additional medication was necessary.

For the iron deficiency anaemia the boy was given iron supplements orally, yet this was stopped soon after due to staining of his teeth.

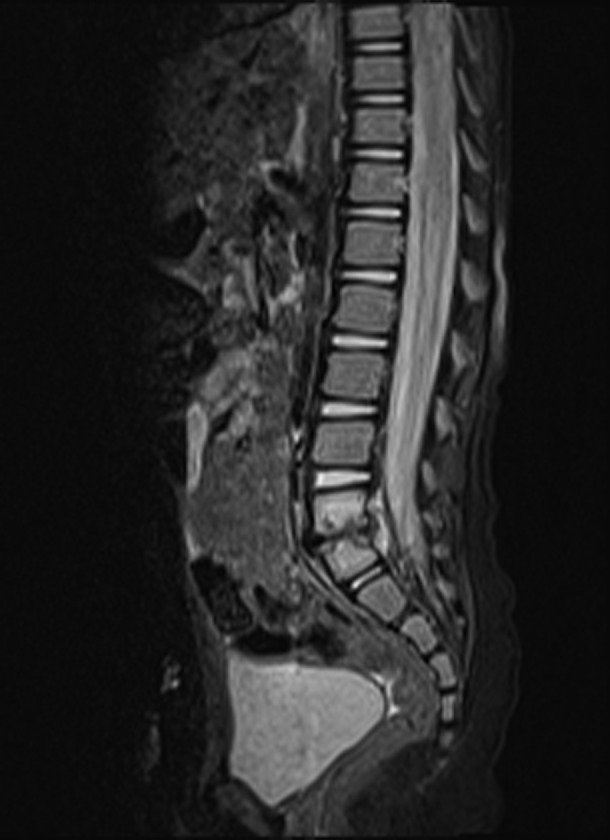

After the above steps the clinical picture improved and the ESR dropped. However, about 2 weeks after admission the ESR started to rise again, although the patient seemed relatively well. A control MRI scan of the lower back was done on 23 January 2012. This MRI showed a significant change in comparison to the previous examination with a marked increase of osseous oedema as well as a further reduction of the intervertebral disc compartment (figure 2). This change was a clear indication for the presence of infectious spondylodiscitis and subsequently intravenous cefotaxime was added to the previously mentioned clindamycin. The cefotaxime was given at a dose of 780 mg three times a day (200 mg/kg/day) and this was given in total for 2 weeks (until the day of hospital discharge). To ease the provision of the antibiotics the patient was fitted with a central venous catheter in the right subclavian vein. With this regime the ESR improved, the clinical picture remained fine and therefore the antibiotic treatment was maintained. As the pain was well controlled, pain relief was reduced to Ibuprofen 100 mg in the evening, reduced to on-demand-medication only on the day of discharge.

Figure 2.

T2-weighted sagittal MRI scan of the spine 2 weeks after diagnosis (23 January 2012).

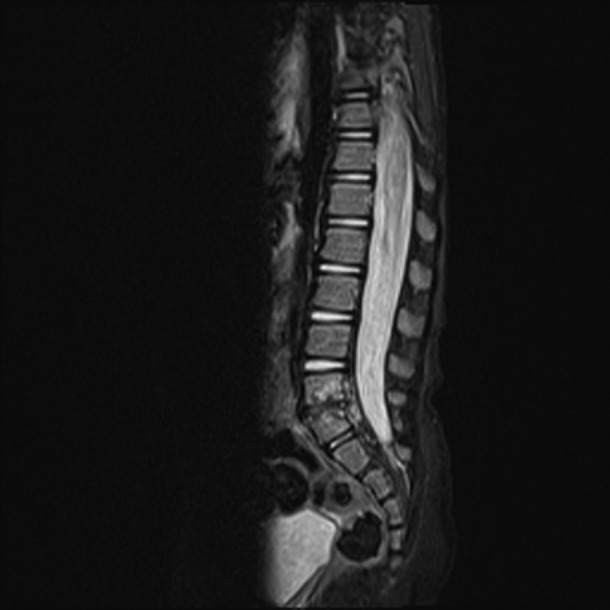

Another MRI scan of the lower back performed on 10 February 2012 confirmed the significant changes mentioned about 2 weeks earlier, yet without further disease progression (figure 3).

Figure 3.

T2-weighted sagittal MRI scan of the spine 4 weeks after diagnosis (10 February 2012).

Outcome and follow-up

Fortunately the patient recovered clinically very well. About 2 weeks after the start of treatment he was crawling again, at about 6 weeks he was walking and hard to stop!

At admission the ESR had been 115 mm and this has fluctuated over time. At hospital discharge it was 20 mm. Table 1 provides an overview on ESR over time.

Table 1.

The patient's ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) over time

| Date, remark | ESR in mm after the first hour (<15, Westergren method) |

|---|---|

| January | |

| 9th (admission, day of diagnosis spondylodiscitis) | 115 |

| 13th | 55 |

| 16th | 55 |

| 19th | 100 |

| 23th (control MRI and adding in second antibiotic) | 175 |

| 26th | 55 |

| 31th | 35 |

| February | |

| 10th (hospital discharge) | 20 |

| 16th | 8 |

| 28th | 7 |

| March | |

| 06th | 4 |

| 20th | 8 |

| April | |

| 24th (gastroenteritis a few days before) | 100 |

| May | |

| 1st (last check before patient returning to the UK) | 47 |

After 5 weeks as an inpatient he was discharged from the hospital, to be reviewed by the GP and by the specialist on an outpatient basis. At discharge the patient was on oral clindamycin (40 mg/kg/day, weight 11.8 kg, advised 160 mg three times a day) and cefixime (8 mg/kg/day, weight 11.8 kg, advised 50 mg twice a day), to continue for another 4 weeks. Pain relief, in the format of ibuprofen, was advised if required only. The patient had to continue to wear the corset.

Approximately 5 weeks after discharge mum presented the patient to the GP. She had noticed that he was often vomiting later on during the day, although he was otherwise fine in himself. On clinical examination no abnormalities could be found. The paediatrician reviewed the patient as well, no clinical explanation could be found for the vomiting, the corset was not too tight and the management was kept the same.

The MRI scan of the lower back from 25 April 2012 showed an ‘Overall obvious improvement with significant regression of the spondylodiscitic signal changes. Only a slight residue in caudal direction below the ligamentum longitudinale posterior with sedimented fibrotic granulomatous material without uptake of contrast media’ (figure 4). It was advised that a repeat MRI scan should be done in about 6–9 months time. As the family were moving to the UK further follow-up will need to be done down there.

Figure 4.

T2-weighted sagittal MRI scan of the spine 14 weeks after diagnosis (25 April 2012).

Discussion

A review of the literature shows that there are many case reports on spondylodiscitis regarding adult and elderly patients, and those from the Mediterranean and the Middle East, yet only some related to children.5 6 Recently a few good reviews about this subject have been published.3 7 8

Definitions vary in the literature. As aforementioned in the background section we have used the definition of spondylodiscitis as an inflammatory disease involving one or more vertebral bodies and the corresponding intervertebral discs.1 However, in paediatrics spondylodiscitis is often just described as discitis (intervertebral disc infection) whereas an infection of the vertebrae is called vertebral osteomyelitis. This differentiation is considered important, as discitis has a more benign course, whereas osteomyelitis requires the aggressive use of antibiotics. Even so, discitis and osteomyelitis are probably part of a continuum of spinal disease and in practice often a mixed picture is found.2

The overall incidence is estimated at between 1:100 000 and 1:250 000 per year. In total, 1, 3, 7, 9–12 spondylodiscitis are mainly a disease of patients above 50 years of age and in this group the incidence is increasing, probably due to the increased life expectancy, chronic debilitating disease, increase in invasive procedures and better diagnostic tools.9–13 However, paediatric spondylodiscitis is uncommon and limited information exists regarding the incidence in childhood.3 This discussion will focus on spondylodiscitis in children.

Regarding the pathophysiology in children, it important to remember that in children the intervertebral discs are still vascularised. Via this direct haematogeneous route the intervertebral disc can be primarily infected and as such can cause a discitis without involvement of the vertebrae.8 However, as aforementioned, at the time of diagnosis usually a mixed picture exists showing damage to both vertebral disc and surrounding vertebrae.13

Especially in infants and toddlers symptoms can be subtle and unspecific. Irritability, increased crying, low-grade fever, refusal to stand or walk, a limp, low back pains but also, for example, abdominal pains, incontinence and constipation have been reported as presenting symptoms. On clinical examination often no specific abnormalities can be found. Some children had a prodromal disease several weeks before presentation, for example a respiratory, gastrointestinal or urine tract infection.3 4 7–9 14 15

Various diagnostic tests are used. Of the blood tests, it is mainly the ESR that can be helpful; it is usually raised at the onset of the disease and it is useful for plotting the clinical course of the condition. However, white blood cell count and CRP are usually within normal limits and blood cultures are usually sterile.1 3 14

Plain x-rays of the spine do not show pathology early on in the disease.3 4 15 An MRI scan is a sensitive and specific test.3 14 15 A bone scan can be positive early on, yet is less specific than an MRI.3 4

A biopsy of the affected area aids setting the diagnosis and the choice of antibiotic treatment, yet in children it is often difficult to obtain and therefore not a standard diagnostic procedure in this group.3 14

The mentioned unspecificity of symptoms, the limited laboratory findings and the late changes in x-rays often lead to a delay in diagnosis. Considerable differences exist in the paediatric literature regarding this issue. For example the mean duration of symptoms until first presentation in the clinic was 24 days (range 4–42 days) in one study, another study indicated this as 8 days (2–20).3 14 The average time between presentation at the clinic and setting the diagnosis was indicated as 18 days (1–42 days), 12 days (7–14 days), respectively, 2 days (0–8 days) in three different studies.3 4 14 The overall process has been reported to take up to 3 months in 50% of cases.3

There are no randomised controlled trials related to the treatment of spondylodiscitis. A few authors suggest that in contrast to the adult form, childhood spondylodiscitis is a benign and self-limiting condition. Because of this, some centres do not routinely prescribe antibiotics and instead recommend analgesia, rest and spinal support.3 4 However, many authors suggest that spondylodiscitis often, if not always, has an infectious origin.1–16 Although a wide range of organisms has been associated with it (bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal and parasitic) it seems primarily a monomicrobial bacterial infection. Staphylococcus aureus is the predominant pathogen, yet a wide range of bacteria has been isolated, including rare microorganisms like Kingella kingae in some paediatric series. Worldwide tuberculosis is the commonest cause and Brucellosis is common in endemic areas like the Mediterranean and the Middle East.6

In children in the Western World often a third generation cephalosporin and oxacillin/clindamycin are prescribed. Usually antibiotics are given intravenously for 1–3 weeks, followed by oral antibiotics for another 4 weeks, and this depends on clinical symptoms and infection parameters, like ESR.3 4 14 15 However, recent trends suggest that shorter lengths of intravenous therapy with an early switch to oral antibiotics is acceptable, yet this is not the case for the management of complex infections, including those with significant bone destruction.17

All children are given a back support (corset) or a body plaster cast with the aim to immobilise the affected area, on average for 15 weeks. Analgesia are prescribed as required.4 14

The overall outcome in children is good; most make a good recovery without significant spine instability or deformity. Even so, radiological abnormalities often persist and long-term follow-up is required.4 14 15

Taking into account this literature review one can conclude the following. Spondylodiscitis in children is uncommon in paediatrics and rare in general practice, often presents with unspecific and atypical symptoms and as such is a diagnostic challenge. This case report showed the clinical picture of a toddler who declined to walk yet otherwise did show unspecific symptoms only. Mainly based on the intuition of the mother and the GP, the boy was presented quickly to the hospital specialist (1 day between start of symptoms and presentation at the hospital clinic). From there, to set the actual diagnosis and to start treatment it took 22 days, the overall process from first symptoms until diagnosis took 23 days. This is in line with the literature, where this whole process is reported to take up to 3 months in 50% of the cases.

In our patient the affected area was thought to involve the vertebral disc but also substantial parts of the adjacent vertebrae. The significant vertebral changes over time indicate that the intensive use of antibiotics can be justified. One can argue about the choice of antibiotics in our case. Initially the radiologists were not able to indicate whether or not the cerebrospinal space was affected, yet the choice of first line antibiotic would have been influenced by the presence or absence of meningitis. Therefore the paediatricians performed a lumbar puncture to detect or exclude this, even before clinical meningeal signs might have appeared. Fortunately the culture was sterile. It was decided to use clindamycin IV (40 mg/kg/day in three doses) as first line treatment, as we were looking for an antibiotic with a good in-bone activity and effectiveness against Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Initially the clinical picture of the patient improved very well on this drug. Unfortunately about 2 weeks later the ESR rose again, although the clinical picture remained fine. The subsequent MRI showed a worsening of the affected disc and vertebrae and in line with guidance from the DGPI (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Infektiologie, that is, German Association for Paediatric Infectious Diseases) cefotaxim IV (200 mg/kg/day in three doses) was added. On hindsight it would have been a better choice to have started the treatment with this combination of antibiotics as opposed to clindamycin on its own. Alternatively, the DGPI suggests that a monotherapy would have been possible as well, but then a third generation cephalosporin should have been used.18

The immobilisation of the spine with a corset and pain relief was spot on. The patient made an excellent clinical recovery and the outcome appears to be good.

ESR and MRI spine where the main tests to set the diagnosis and if, on hindsight, these had been done sooner, the diagnosis could have been set earlier. However, spondylodiscitis is seen infrequently and doing an MRI on all children with similar symptoms would have significant resource implications and may cause iatrogenic damage due to false-positive results. On the contrary assessing ESR is relatively cheap and easy to do. A raised ESR in the child that declines to walk could then be the impetus for performing an MRI scan of the hips and spine. It is hoped that this case report may help in the debate around this issue.

Learning points.

Children are naturally inquisitive and walking is a quick way to explore their environment. Children who do not walk should be taken seriously.

Good general practice is about listening to the patient. We all remember events when the mother's intuition was correct—but is this related to recall bias?

Uncommon and rare disease does occur in general practice. Doctors should keep an open mind for the unexpected and search for alternative explanations for their patients’ complaints.19

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and MRI spine are the main tests for setting the diagnosis of spondylodiscitis. Used early in children who refuse to walk and/or with other unspecific symptoms will prevent delay in diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Jorge V, Cardoso C, Noonha C, et al. Fungal spondylodiscitis in a non-immunocompromised patient. BMJ Case Rep 2012; 10.1136/bcr.12.20011.5337, Published 8 March 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez M, Carroll CL, Baker CJ. Discitis and vertebral osteomyelitis in children: an 18-year review. Pediatrics 2000;105:1299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Moreas Barros Fucs P, Meves R, Yamada H. Spinal infections in children: a review. Int Orthop (SICOT) 2012;36:387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrasenan J, Klezl Z, Bommireddy R, et al. Spondylodiscitis in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93–B:1122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arthurs O, Gomez A, Heinz P, et al. The toddler refusing to weight-bear: a revised imaging guide from a case series. Emerg Med J 2009;26:797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim S, Sinnathamby W, Noordeen H. Refusal to walk in an afebrile well toddler. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarghooni K, Röllinghoff M, Sobettke R, et al. Treatment of spondylodiscitis. Int Orthop (SICOT) 2012;36:405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouliouris T, Aliyu S, Brown N. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:iii,11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Citak M, Backhaus M, Kälicke T, et al. Myths and facts on spondylodiscitis: an analysis of 183 cases. Acta Orthop Belg 2011;77:535–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Agostino C, Scozolini L, Massetti A, et al. Seven–year prospective study on spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and microbiological features. Infection 2010;38:102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bettini N, Girardo M, Dema E, et al. Evaluation of conservative treatment of non specific spondylodiscitis. Eur Spine J 2009;18:143–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobottke R, Seifert H, Fätkenheuer G, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis. Dtsch Arztebl 2008;105:181–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hildebrandt J, Müller G, Pfingsten M. Endzündliche Wirbelsäulenerkrankungen (Spondylitis und Spondylodiszitis, in Lendenwirbelsäule—Ursachen, Diagnostiek und Therapie von Rückenschmerzen. Elsevier: München, 2005:548–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waizy H, Heckel M, Seller K, et al. Remodeling of the spine in spondylodiscitis of children at the age of 3 years and younger. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007;127:403–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plasschaert H, De Geeter K, Fabry G. Juvenile spondylodiscitis: the value of magnetic resonance imaging. A report of two cases. Acta Orthop Belg 2004;70:627–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerado E, Cervan A. Surgical treatment of spondylodiscitis. An update. Int Orthop (SICOT) 2012;36:413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faust SN, Clar J, Pallett A, et al. Managing bone and joint infection in children. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DGPI Handbuch, Infektionen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen, 5., vollständig überarbeitete Auflage, George: Thieme Verlag KG, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godlee F. On keeping an open mind. BMJ 2011;343:d7125. [Google Scholar]