Abstract

Smaller firms are the majority in every industry in the US, and they endure a greater burden of occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities than larger firms. Smaller firms often lack the necessary resources for effective occupational safety and health activities, and many require external assistance with safety and health programming. Based on previous work by researchers in Europe and New Zealand, NIOSH researchers developed for occupational safety and health intervention in small businesses. This model was evaluated with several intermediary organizations. Four case studies which describe efforts to reach small businesses with occupational safety and health assistance include the following: trenching safety training for construction, basic compliance and hazard recognition for general industry, expanded safety and health training for restaurants, and fall prevention and respirator training for boat repair contractors. Successful efforts included participation by the initiator among the intermediaries’ planning activities, alignment of small business needs with intermediary offerings, continued monitoring of intermediary activities by the initiator, and strong leadership for occupational safety and health among intermediaries. Common challenges were a lack of resources among intermediaries, lack of opportunities for in-person meetings between intermediaries and the initiator, and balancing the exchanges in the initiator–intermediary–small business relationships. The model offers some encouragement that initiator organizations can contribute to sustainable OSH assistance for small firms, but they must depend on intermediaries who have compatible interests in smaller businesses and they must work to understand the small business social system.

Keywords: Small business, Occupational safety and health, Intervention model, Diffusion, NIOSH

1. Introduction

Smaller businesses (those with fewer than 20 employees) make up a majority of firms in every major sector of the U.S. economy (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2011). They serve a critical function within the economy as they create more new jobs than larger businesses (Headd, 2010). There is a significant body of literature which suggests they endure a greater burden of occupational illnesses, injuries, and fatalities than their larger counterparts (Buckley et al., 2008; Fabiano et al., 2004; Fenn and Ashby, 2004; Hinze and Gambatese, 2003; Jeong, 1998; Mendeloff et al., 2006; Morse et al., 2004; Okun et al., 2001; Page, 2009). While smaller firms have been suggested to be more flexible and able to adapt to market trends (Vossen, 1998), they are also described as isolated and lacking the necessary “slack” resource capacity for engaging in occupational safety and health (OSH) activities (Page, 2009). Although small business OSH has received limited research attention, much of what is known thus far suggests a need for not only effective OSH interventions, but also a critical need for better understanding ways to develop OSH resources external to small businesses which can and will be easily employed for improved small business OSH outcomes.

1.1. Foundational research

Researchers in Denmark and New Zealand have recently proposed models for reaching small businesses with safety information and services based on their experiences in those countries (Hasle et al., 2012, 2010; Hasle and Limborg, 2006; Olsen et al., 2012). These researchers introduced the concept of intermediary organizations (organizations that deliver goods or services to small businesses) as delivery channels between initiator organizations (often governmental public health/safety organizations) and small businesses as a means to overcome the resource scarcity issue, and they have demonstrated promising results. For example, Hasle et al. (2010) demonstrated that accountants can effectively serve as intermediaries for transmitting OSH information to small enterprises and the experience is positive for them; however, the effort was hindered by the low priority of OSH on the accountants’ agenda with their clients, and the authors concluded outside resources would be needed to sustain accountant training and interest in engaging their clients on OSH issues.

2. An extended model for small business OSH intervention

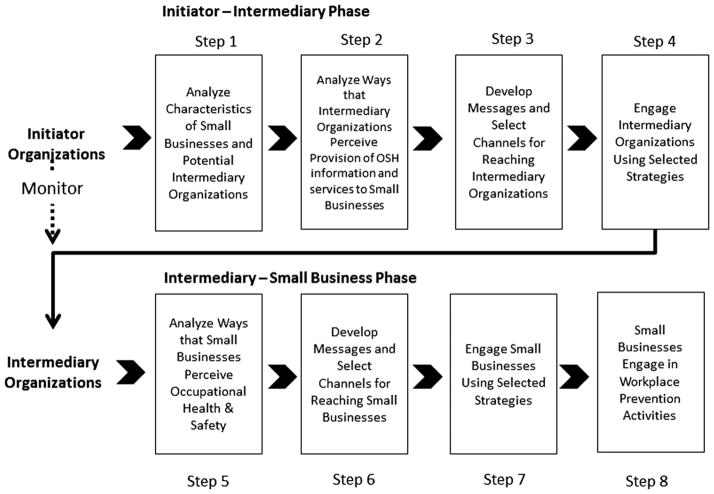

Based on the present authors experience at the National Institute for Occupational safety and Health (NIOSH), in the US, an extended model for small business (SB) OSH intervention has recently been proposed (Sinclair et al., 2013) (Fig. 1). It may also be termed as an ‘initiator–intermediary–small business diffusion model’. It hypothesizes that in order for it to work, initiating organizations must focus on intermediary organizations as much as they focus on SBs because both have to be motivated to interact. In the US initiators predominately lack the authority to mandate the OSH assistance relationship between intermediary and small business. Initiators such as NIOSH have had to rely on dissemination strategies that rely on information-seeking of small business owner/managers (e.g. posting materials online) or methods such as direct mailing, which has limited effect in transmitting OSH information to small businesses (Schulte et al., 2003; Welbourne and Booth-Butterfield, 2005). Thus it is hypothesized that OSH must offer an added business value for both intermediaries and SBs for these targeted parties to engage in any sort of OSH service assistance, product, or information supplying relationship.

Fig. 1.

A model for occupational safety and health intervention for small business (Sinclair et al., 2013).

The model uses an appropriate lens for investigation and application, focusing on a social system of influences on organizations (Eakin et al., 2010). It was developed by the authors over the past four years as managers of the Small Business Assistance and Outreach Program of NIOSH, and was informed by the case studies described in this paper. The primary influences on this model are social exchange theory and the diffusion of innovations model.

Social exchange theory presumes an intuitive cost-benefit analysis drives human relationships between individuals and organizations (see Miller, 2005 for an introduction). If the costs exceed the benefits, the relationship will not survive. SBs often have relationships with goods and service providers that involve not only an economic exchange, but also a social exchange. This perspective refocuses OSH initiators on how to convince intermediaries on either an economic or social exchange basis, offering OSH assistance will enhance their value to SBs. Thus, the initiator must demonstrate the value of OSH to both intermediaries and the SBs they serve.

The diffusion of innovations model is one of the practical models in the fields of marketing and organizational communications (Miller, 2005) that use social exchange theory. It maps how new ideas move through a social system over time (Rogers, 2003). OSH may not necessarily be seen as an innovation, but it is often new to smaller firms (Sinclair et al., 2013). The diffusion model focuses on characteristics of the intervention, characteristics of the target audiences, communication channel selection, and time to adoption. It has been used extensively to investigate the adoption of innovations by organizations and individuals, particularly in public health and healthcare (Brownson et al., 2007; Cragun et al., 2012; Greiver et al., 2011; Pombo-Romero et al., 2012; Rogers, 2003).

The elements of the extended model for SB OSH intervention (Fig. 1) offer guidance for both the “initiator to intermediary” phase (top half of Fig. 1) and the “intermediary to small business” phase of diffusion (bottom half). The steps in each phase are similar, but different types of organizations execute them to achieve different objectives. Initiators most commonly have a public health mission. However, other types of organizations without sufficient resources to achieve system-level SB OSH objectives might be initiators. It is important to note that the steps in the model are not necessarily conducted discretely and sequentially. That is, much of the activity among the different steps occurs iteratively or simultaneously.

2.1. Initiator to intermediary phase (Steps 1–4)

In Step 1, the initiator identifies the OSH needs of smaller firms in its geographic area and the characteristics of intermediaries that serve them. OSH needs are identified using data from community sources such as health departments, workers’ compensation insurers, occupational health clinics and community leaders. Then the initiator works to find and understand organizations it can persuade to start or increase their delivery of OSH information, products, or services to SBs. These might be organizations already engaging SBs in OSH assistance, looking for new ways to engage small firms, or already well-connected to a small business network. The range of intermediaries includes suppliers of goods and services (equipment/material suppliers, insurance companies, legal and financial advisors, health providers), membership organizations (trade associations, chambers of commerce), education organizations (community colleges, vocational schools), and government agencies.

In Step 2, the initiator works to understand how selected intermediaries perceive OSH assistance for SBs. Perceptions of new products or ideas that affect their appeal include relative cost, advantages over other options, compatibility with existing systems, lack of complexity, trialability, and easily observable results of adoption (Dearing and Meyer, 1994; Rogers, 2003). It follows intermediaries will be more accepting of the idea of adding OSH products and services if they perceive it as having as many of those characteristics as possible. Step 2 is complete when the initiator understands how intermediaries view OSH’s potential to add to their exchanges with SBs.

In Step 3, data from Step 2 are used to make decisions about message content and channels for delivery. As the initiator learns about perceived strengths and weaknesses of OSH programming and as those perceptions change over time, it adjusts its messages for intermediaries. Intermediaries must be convinced to commit resources beyond what they are currently offering for SB OSH assistance, and in the authors’ experience decision makers are most effectively convinced by face-to-face interaction. However, channels such as webinars and social media might be used.

In Step 4, the initiator engages intermediaries using strategies selected. Unless those in the organization see something is affecting organization performance, changes are unlikely. Recognition of a deficiency is followed by a search for interventions that lessen or eliminate the deficiency, changes in the organization, and the intervention to improve fit. When the best fit is found, the organization makes the intervention a routine part of operations (Rogers, 2003). The initiator to intermediary phase is complete when targeted intermediaries decide to offer SBs more OSH assistance.

2.2. Intermediary to small business phase (Steps 5–8)

In Steps 5 through 8, intermediaries engage SBs using the same process that the initiator used to engage intermediaries (see Fig. 1). They work to understand the needs of SB targets and their attitudes toward OSH (Step 5). They develop or select OSH products or services they can offer and that will be valued. Then they develop strategies to make SBs aware of what they now offer (Step 6). In Steps 7 and 8, they engage the businesses and deliver the products or service which are then used by the businesses. Throughout, the initiator should monitor these steps. The initiator is especially interested in Step 8 because that is the point at which employers take action for prevention that leads directly to less workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities.

2.3. Aims

There has been a call for more case studies to demonstrate promising practices for moving smaller enterprises to action for workplace injury and illness prevention (Laird, 2013). Previous reviews found few intervention studies showing strong or even moderate evidence for improved OSH outcomes in SBs (Breslin et al., 2010; Hasle and Limborg, 2006; Legg et al., 2009). At the recent Understanding Small Enterprise conference, the need for more case studies was a prominent theme (Laird, 2013). There have been collections of case studies of SB OSH interventions (Antonelli et al., 2006) which can be useful in conveying the business value of OSH to SBs. However, there are few SB OSH studies which report on intervention diffusion from the initiator’s perspective (Dugdill et al., 2000). The aim of the paper is to present the application of the extended model for SB OSH intervention and to assess the usefulness of the model in evaluating the roles of and relations between initiator and intermediaries through a series of four case studies that relied on intermediaries to reach SBs and to deliver an intervention.

3. Method

The model described above is tested on four case studies: trenching safety training for construction, basic compliance and hazard recognition for general industry, expanded safety and health training for restaurants, and fall prevention and respirator training for boat repair contractors. The model is used to analyze four OSH interventions for SBs initiated and evaluated by NIOSH. The targeted SBs in each case study were selected primarily on the availability of good potential intermediaries and because the targeted SB belonged to a sector with higher than average injury and illness rate. In each of the four cases described below, NIOSH served as the initiator as well as the evaluator. Additionally, the cases occurred sequentially, so that NIOSH experiences as the initiator informed subsequent replications in different environments. As an example, the mix of intermediaries targeted and the assistance offered as an initiator by NIOSH in the small shipyard case was largely based on experiences in the trenching safety for construction case.

Evaluation was conducted by NIOSH using observer-participant methods, and was informed by multiple sources. Evaluation of three of the cases was primarily based on a questionnaire survey of the intervention attendees from SBs. The questionnaire gathered data including demographics, promotion channels, perceived value of OSH content, and behavioral intentions. These case studies were further evaluated based on the data NIOSH gathered after the intervention through communication with the intermediaries about their perceptions of their intentions to continue the activity that constituted the intervention, the benefit they had from the intervention, and the value of the intervention to SBs.

The steps in the model were applied in each case not in discrete sequence, but rather in an iterative fashion grouped into the two main phases of the model. The four cases were analyzed and information about the 8 phases of the model were extracted and placed into tables. The model was used as an analytical tool rather than a planning model for the intervention. The specific steps of the model as applied in each case are detailed in Tables 1–4, not to imply sequential occurrence but rather to identify activities undertaken by the initiator and intermediaries that correspond with the steps in the model.

Table 1.

Summary of trenching safety training for construction case study.

| SB OSH model steps | |

| Intervention |

|

| Initiator–intermediary phase | |

| 1. Analyze characteristics of SBs and potential intermediaries |

|

| 2. Analyze ways that intermediaries perceive provision of OSH info. and services to SBs |

|

| 3. Develop messages and select channels for reaching intermediaries |

|

| 4. Engage intermediaries using selected strategies |

|

| Intermediary–small business phase | |

| 5. Analyze ways that SBs perceive OSH |

|

| 6. Develop messages and select channels for reaching SBs |

|

| 7. Engage SBs using selected strategies |

|

| 8. SBs engage in workplace prevention activities |

|

| Lessons learned |

|

Table 4.

Summary of expanded safety and health training for restaurants case study.

| SB OSH model steps | |

| Intervention |

|

| Initiator–intermediary phase | |

| 1. Analyze characteristics of SBs and potential intermediaries |

|

| 2. Analyze ways that intermediaries perceive provision of OSH info. and services to SBs |

|

| 3. Develop messages and select channels for reaching intermediaries |

|

| 4. Engage intermediaries using selected strategies |

|

| Intermediary–small business phase | |

| 5. Analyze ways that SBs perceive OSH |

|

| 6. Develop messages and select channels for reaching SBs |

|

| 7. Engage SBs using selected strategies |

|

| 8. SBs engage in workplace prevention activities |

|

| Lessons learned |

|

4. Case study 1: trenching safety training for construction

For this first demonstration, an intervention consisting of a ½ day training course on trenching safety was delivered by a state-based Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) program, a supplier of trenching safety equipment, and a state chapter of a national construction trade association, with the venue supplied by a community college. Course content included regulatory requirements, safe work practices, and a demonstration of proper trenching safety equipment rigging and use, and the cost to participants ranged from $25 for early registration to $40 for onsite registration.

4.1. Initiator to intermediary phase

NIOSH was aware of trenching incidents being a leading cause of illness, injury, and fatality based on surveillance data for the construction industry (CPWR, 2008). With the aim of piloting an initiator–intermediary–small business approach to providing OSH assistance to SBs, the authors became acquainted with a representative of the state-based OSHA program in Kentucky (KY) at one of their local safety outreach events. The OSHA representative also referred NIOSH to the other two intermediaries who participated in the first phase of this case: a trenching equipment supplier in Ohio and the KY chapter of a construction trade association.

The OSHA representative identified trenching as being a particular area of concern in construction, with trenching included as an emphasis area for compliance inspections. He reported small contractors were more likely to not use recommended trenching safety equipment. He said there was not enough training offered on trenching, and KY OSHA was eager to deliver training events to SBs. Most OSH training included trenching as a brief component of more comprehensive training programs such as the OSHA 10-h training course for construction (Sokas et al., 2009).

The trenching equipment supplier in Ohio regularly offered trenching-specific OSH training to its customers free of charge. The training was an innovative way to add value to its relationships with its small construction customers. The president of the company also used knowledge of several incidents that resulted in serious injury and fatality due to trench collapse and rigging malfunctions during trenching operations to remind customers of the benefits of trench boxes, a primary protection.

The KY chapter of a construction trade association was already engaged in offering OSH training to its members, and was interested in seeking new ways to reach SBs. The chapter’s safety training director recognized the need for more trenching-specific training particularly among SBs. He also said the chapters of the organization were in competition with each other for “best chapter” awards and added OSH programming might help the chapter.

NIOSH brought the three intermediaries in contact with each other and highlighted to each intermediary how they could benefit from collaboration. By working together, each intermediary would get a chance to test the compatibility of providing the additional safety information provided by the other intermediaries with the services they offered customers. The equipment supplier could provide on-site equipment and demonstration of work practices, KY OSHA offered an authoritative source of information about hazard control, and the trade association offered in-depth knowledge of and connections within the industry. Communications from NIOSH to each of the intermediaries also emphasized the significant proportion of small contractors in Kentucky and the opportunity to reach them with effective OSH training. Finally, NIOSH offered to assist in developing, promoting, and evaluating a collaborative training to gauge its effectiveness in improving injury prevention skills and perceptions about the organizations involved.

4.2. Intermediary to small business phase

Based on previous experiences working with small contractors, the intermediaries identified the need for basic trenching safety training. They identified a need for trenching safety classes to be delivered to small contractors not mainly engaged in trenching activities (e.g., plumbers and foundation repair specialists). They decided training should be offered early in spring before the work season ramps up, should last half a day, and must be low-cost to allow small contractors to afford sending more than one employee when possible. They also decided the audience would benefit from on-site demonstrations of trench box rigging and placement rather than exclusively classroom material.

The intermediaries identified networks to reach small contractors including local chambers of commerce, the equipment supplier’s clients, trade association members, an affiliated trade association specifically for plumbing and heating contractors, and the KY OSHA email listserv. The flyer promoting the training focused on regulatory requirements specific to trenching and the opportunity for on-site demonstration of the latest equipment used in trenching. The intermediaries produced flyers that they faxed (3000 trade association members), emailed (40,000 OSHA listserv subscribers), direct mailed (525 equipment supplier clients), and hand delivered (75 equipment supplier clients) to potential attendees. Distribution occurred approximately 3–4 weeks prior to the event. Additionally, press releases were published the morning of the first class, although only one attendee reported finding out about the class from the press release.

The intermediaries also collaborated in preparing the course content. An agenda was developed and revised, areas of overlap were identified, and content was altered to maximize coordination among the training components. KY OSHA covered the regulatory compliance requirements for trenching, the trade association contributed technical content related to best practices for trenching safety, and the equipment supplier contributed a demonstration of proper equipment rigging and use for trenching activities. Additionally, the trade association secured a community college as the location in exchange for free attendance for students in the construction vocation program.

The intermediaries conducted the course four times in sessions offered over two days. A total of 80 students attended. SB attendees included 33 individuals from a total of 13 firms with fewer than 50 employees. NIOSH monitored the courses, capturing photographs and video, and assisted with an evaluation of the event, which indicated attendees (on average):

Rated the trenching safety class as useful to very useful (n = 69, average = 4.5 on 5-point Likert scale: 1 = not at all useful –5 = very useful, 62 responded useful or very useful).

Reported moderate to minimal engagement in trenching activities (n = 69, average = 2.6 on 5-point Likert scale: 1 = never engaged in trenching, 3 = sometimes [50% or less involves trenching], 5 = trenching is all we do, 40 responded 50% trenching or less).

Were likely or certain to apply what they learned in the class to their business (n = 69, average = 4.5 on 5-point Likert scale: 1 = definitely not – 5 = certain, 58 responded likely or certain).

Would likely attend future construction safety demonstrations for other activities (n = 69, average = 4.4 on 5-point Likert scale: 1 = definitely would not attend – 5 = certain to attend, 59 responded likely or certain).

Of the 17 firms in attendance, 13 had less than 50 employees. The majority of SBs in attendance were involved somewhat with trenching activities, but trenching was not necessarily their dominant area of work. Most SBs that attended the event sent multiple employees. Thus, the event was somewhat successful in engaging small construction businesses whose work involves some trenching, and the cost and timing were appropriate for the target audience.

The event also demonstrated positive impact by high participant ratings, and responses indicating their likelihood for applying what they learned to their own business as well as for attending future construction safety demonstrations. The channels through which SB attendees became aware of the training course were evenly spread among the intermediaries (6 SB attendees each from the equipment supplier client list, trade association, and KY OSHA). However, the equipment supplier distributed course information to far fewer individuals than the other intermediaries (600 clients vs. 40,000 on OSHA listserv). This suggests equipment suppliers may be more effective channels for transmitting OSH information to SBs.

4.3. Lessons learned

The equipment supplier and the trade association collaborated on a similar trench safety training event approximately six months later. Held at a hotel near Lexington, KY, they were so convinced of the effectiveness of the trench box placement and proper rigging and lifting portions of the original event they secured permission from the hotel owner to excavate a training trench and place a trench box in the lawn of the hotel. This offering of OSH content to SBs independent of the initiator is evidence the intermediaries had truly perceived value in the effort for their own organizations, and that the intervention is sustainable on the intermediary level because it has benefit to the intermediaries. This is the key behavior outcome envisioned by the model.

Despite the clear value of the intervention to the intermediaries involved in this case, it is likely the effort would not have continued without the leadership for OSH in both the trade association and the equipment supplier. These individuals became the driving force behind the sustained intervention effort, and they were clearly opinion leaders in OSH among the target group in the construction industry. Thus, it is crucial not only to find good potential intermediaries that will be able to reach SBs with OSH assistance, but also to identify individuals within those intermediaries that can champion the effort.

5. Case study 2: fall prevention and respirator use training for boat repair contractors

In this case NIOSH attempted to replicate the model used in the previous case for the delivery of a training intervention to small contractors working in boat repair facilities in southern Florida. The focus of training was to include fall prevention and respirator use, and was to be delivered by intermediaries including a marine industry trade association, a local OSHA office, a yacht repair facility, and a local safety trainer. However, the intervention was not delivered and some contributing factors to the effort’s failure are explored below.

5.1. Initiator to intermediary phase

In 2010, NIOSH attempted to increase OSH training for subcontractors working in the small ship and boat repair industry in southern Florida, which is home to more boatyard facilities than any U.S. region (U.S. Dept. of Commerce, 2011). This industry was selected because of high incidence rate (7.2–7.9 per 1000 full time workers [U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010]) and the opportunity to replicate the model used in case study 1 in a new setting. Ship and boat building and repair activities often include exposure to toxic substances, hazardous atmospheres, electrocution, falls, fires, and explosions. A regional OSHA representative reported they knew little about specific hazards encountered in small boatyards and subcontractors working there because they are difficult to access.

The yacht repair facility manager reported most of their contractors had 10 or fewer employees. He said safety compliance was a constant challenge, as well as environmental compliance, and noted confined spaces, painting operations, and working from scaffolding as persistent difficulties. His organization did not offer training to contractors, but did refer them to a safety trainer. He wanted all contractors to have a basic OSH credential (OSHA 10-h shipyard certification), but his organization did not require certification. He was an active member of the local marine trade association. He had also developed an air filtration system for use while painting in confined spaces. His organization was clearly connected to SBs, open to changes in OSH policy, and innovative in OSH technology.

The local safety trainer indicated the persistently difficult hazardous activities to address with contractors were paint removal, paint application, and use of scaffolding. He trained several contractors around the region and had developed a program to assist anyone using scaffolding by conducting inspections and offering informal instruction in proper erection. He was interested in reaching more SBs with OSH training services; however, he recognized many small contractors felt they could not afford to send their employees to his OSHA 10-h shipyard course.

The trade association was composed of approximately 800 members, a majority of which were smaller businesses. In addition to the typical advocacy and networking functions they provided services to members including human resources and financial training. The director reported they recently discussed offering basic safety training to members, and were motivated to do so to be proactive and avoid regulatory interference in the industry as well as for membership in the organization to symbolize professionalism, which they thought should include basic OSH competence.

While there was agreement among the intermediaries that basic OSH training should be offered to small contractors working in boatyards, it was unclear what content should be included. As a component of training development, NIOSH interviewed boatyard operators and contractors to assess perceived risks and specific training needs, and shared data with the intermediaries. Results indicated:

Contractors were uncertain which OSH standards were relevant.

Important issues were fall prevention, respiratory protection, fire prevention, and chemical info.

Some were willing to pay up to $200 per person for training while

Others emphasized minimal cost and duration to enable all employees to attend.

Language was a barrier for contractors with Vietnamese and Spanish-speaking employees.

Contractors see value in OSH training as professionalism and want to market that aspect of business.

The trade association and yacht repair facility agreed training should be delivered in four four-hour sessions in June 2011 to accommodate seasonal work schedules. The trade association would cover costs of trainers, and a registration fee of approximately $50 per participant (estimated 100 participants ~$5,000) would cover costs of course materials. Facility costs would be donated by the yacht repair facility. However, in April 2011 there was a change in leadership within the trade association, and the new director discontinued the collaboration. The new director reported one member previously had a negative experience with NIOSH and the association no longer wanted to pursue the collaboration. It was unclear what the negative interaction had been, but the collaboration did not continue.

5.2. Intermediary to small business phase

Although this demonstration ultimately failed to result in assembling a collaboration of intermediaries to deliver OSH, there were some positive outcomes. An OSH training session at the annual meeting of the national trade association was modified to focus specifically on topics identified in the focus groups and discussions with intermediaries – respirator use and fall prevention. Additionally, focus group results provided basic market research for the regional trade association. That is, the concept of OSH competency as a demonstration of professionalism may lead association leaders to consider adding OSH assistance services to its membership benefits.

During the initial phase of the demonstration, NIOSH consulted with the local safety trainer on revising his training evaluation to measure behavioral intentions specific to training content as well as perceptions of value-added due to OSH training. The enhanced evaluation instrument may have led to improvements in safety training delivered in local boat repair facilities, but no follow-up data were collected. Finally, the yacht repair facility reported in June 2011 they hired a safety consultant and were planning to develop a safety training program for contractors working on-site.

5.3. Lessons learned

A lack of leadership, or a clear champion was a significant barrier to the successful implementation of the model in this example. The safety trainers were certainly enthusiastic about the effort, but lacked the status of opinion leadership among the intermediaries assembled. The trade association and yacht repair facility held greater opinion leadership status, but were unwilling to champion a collaborative effort. While NIOSH may have influenced the intermediaries to do more in the realm of OSH for the SBs they reach, the continued presence of the initiator is not necessary for the intermediaries to offer added OSH services to SBs. The collaborative effort did not continue, but each intermediary individually did engage SBs with new OSH content or extended OSH assistance outreach. This suggests a need for redefining success within the framework of application for the model, with greater emphasis on monitoring intermediary–small business interactions.

As initiator, NIOSH should have done more follow-up work to understand the negative experience of the trade association member. They likely perceived NIOSH as being part of OSHA or confused the NIOSH mission with that of a regulatory agency. This suggests NIOSH should have focused more on identifying and understanding the perspective of opinion leaders in the association. A lack of geographic proximity between the initiator and intermediary organizations was also a challenge, as face-to-face meetings were difficult to coordinate during limited travel opportunities. Once the trade association backed out of the collaboration, it was difficult for the initiator to justify continued travel costs. Despite these difficulties, NIOSH should have explored additional communication channels with the intermediaries such as regional conferences or webinars.

6. Case study 3: basic compliance and hazard recognition for general industry

For this demonstration, an intervention consisting of a half-day training class covering the economic case for OSH, basic OSH compliance, hazard identification, and information on workers compensation insurance premiums was delivered through a group of chambers of commerce in Miami County, Ohio. NIOSH collaborated with a group of three city-based chambers within the county as well as the Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation and the Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center to deliver the training content and evaluate the class.

6.1. Initiator–intermediary phase

In the US, chambers of commerce are perhaps the most obvious choice as intermediaries that reach a large number of SBs. There are thousands of them with millions of small (and large) business members. Their function is to boost the success of their members through promotion to customers, policy advocacy with government, networking events and professional development programming.

NIOSH was aware that most SBs in the US engage in very few OSH activities (Sinclair and Cunningham, 2014) and given the need for greater external assistance for OSH in SBs, adding to or improving OSH programming among chambers holds good potential for impacting OSH in SBs. NIOSH joined two chambers of commerce in 2009, one with 1200 and another with almost 5000 members. The aim was to learn about the chambers and assess how they could be used as intermediaries to reach SBs with information about OSH. Both chambers had committees and programming in OSH-related areas such as human relations, health, and small business development, and the authors joined several committees including workplace safety committees in each chamber. Through those meetings and examination of the strategic plans of the chambers, NIOSH learned to be sure suggestions about increases in OSH programming fit with the strategic goals of the chamber and the needs of its SB members. NIOSH also saw the chambers were highly skilled at promoting and staging programming for businesses.

Through the larger chamber, NIOSH learned about a state-wide program of support for OSH programming offered by chambers. The Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation (the Bureau) supports the operation of 80 safety councils in the State. Most are operated by local or county chambers of commerce as agents for the Bureau. All conduct monthly meetings on OSH issues for businesses in their area. However, the meetings were not specifically targeted for SBs. Each managing chamber conducts programming needs assessment with those businesses relatively independently, with input from the Bureau. Some businesses are part of a program offering reduced workers’ compensation premiums for both regular and consistent attendance at safety council meetings. In the fall of 2009, NIOSH began accepting invitations from individual councils to provide OSH programming at monthly meetings. Over a two-year period, the authors gave presentations to 18 safety councils on a variety of topics.

In 2010, a group of 3 chambers of commerce operating as one of the safety councils in Miami County, OH invited NIOSH to provide a training event for its members. Their assessment of their members indicated a need for basic OSH compliance training across a variety of industries, as well as a need for greater understanding of workers compensation insurance. NIOSH agreed to contribute to a training event on condition the content and promotion of the event targeted SBs, noting to the chambers that providing OSH programming aimed specifically at SBs may influence their SB members to perceive their membership as being more valuable. NIOSH also invited the Bureau and Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center to collaborate in providing training content. For the chambers, this was an experiment in attracting and serving SBs specifically, rather than as part of a larger group. For NIOSH, it was a chance to test how chambers and other intermediaries could package OSH content in ways palatable for SBs.

6.2. Intermediary–small business phase

NIOSH conducted a half-day training class in Miami County, Ohio on OSH for area SBs in 2010 in conjunction with the group of three city-based chambers within the county. The training consisted of sessions on (a) the economic case for SBs to attend to OSH, (b) an introduction to fifteen safety and health topics classified as important to SBs by OSHA (U.S. Dept. of Labor, 2010), (c) hazard mapping (a small group hazard recognition exercise), and (d) basic information about workers’ compensation premium calculations for SBs. The Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center and the Bureau covered the first and last segments respectively, and NIOSH staff covered the second and third segments. Thus, the initiator was working with three intermediaries.

The event was announced through each of the chambers email lists (413, 346, and 175 members), and was promoted as a workshop for SBs to learn basic facts about OSH compliance and workers compensation insurance. The cost for attendees was $50 per participant. The event was attended by 26 employers, 20 of which employed less than 50 workers. After the event, participants reported (on average) they were more likely to:

View the cost of an OSH program as more valuable than they did before the event (18 of 26 likely or certain to do so).

Engage in workplace inspections more than they did before the event (24 of 26 likely or certain to do so).

Use the U.S. OSHA website more than they did before the event (20 of 26 likely or certain to do so).

A majority (16 of 26) also responded offering more workplace health and safety-related programming would be likely or certain to increase the value of chamber membership. According to follow-up discussions, all the intermediaries involved saw benefits of involvement in OSH promotion with SBs.

6.3. Lessons learned

As initiator, NIOSH learned small chambers could market and execute one-time OSH training for SBs, although not without considerable outside content expertise. Smaller chambers are just as skilled at organizing, promoting and staging programming for SBs as their larger chamber counterparts. However, they are somewhat reluctant to market specifically to SBs in a desire to not leave out any member. Smaller chambers may be more willing to experiment in what they are willing to offer to their members than the larger chambers NIOSH joined. But this advantage is tempered for initiators by their limited resources for programming and their limited reach. At the intermediary level, the three small chambers learned an event with strictly OSH programming could be successful with their members. But since NIOSH did not offer them more in terms of ways to access OSH expertise in their geographic area, they have not offered similar subsequent programming. In essence, this experience revealed the conduit for OSH programming was present, but the content would likely have to come from elsewhere. Initiators need to be sure inexpensive and flexible OSH programming resources are available to chambers, and the benefits of adding such programming are recognized and acted upon.

Additionally, the lack of sustainability for this case again demonstrates the need for identifying a clear opinion leader within an intermediary that can influence change for adding greater OSH assistance offerings for SBs to the organization’s programming. The chambers were most influenced by the directives of the Bureau, and did not have a clear opinion leader within the organization to advocate for SB OSH. As an initiator, NIOSH may be more effective in developing sustainable SB OSH assistance by working to influence opinion leaders within the Bureau who can in turn influence chambers in Ohio to do more for SBs in OSH.

7. Case study 4: expanded safety and health training for restaurants

In this case, NIOSH participated in an ongoing training effort being led by a state-level trade association in the food service sector. NIOSH contributed training content on the topics of hazard mapping and safety climate development over a series of 12 training events during the course of 3 years, which included both webinars and in-person presentations.

7.1. Initiator–intermediary phase

In 2010, there were more than 581 thousand eating and drinking places in the US, and 350 thousand of them employed fewer than 20 workers. Those smaller establishments employed more than 1.9 million people (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2011), and workers in the industry experienced workplace injuries at the rate of 3.3 per 100 workers per year) (U.S. Department of Labor, 2010). There are a variety of occupational hazards in the industry including hot surfaces, knives and other cutting devices, slippery surfaces, and violence (Filiaggi and Courtney, 2003).

The industry may be roughly divided into fast-serve, full service, and institutional types with franchise and independent owner operations. Workers in the industry generally make lower wages. Turnover is higher than most industries, so training and retraining of workers is an industry fixture. The industry is competitive retail, and three of five new businesses fail or change ownership in the first five years (Parsa et al., 2005). The industry is served by a variety of vendors of food, kitchen and dining room equipment, and professional services. It is served by trade associations that organize and recruit members at the national, state, and local levels. Restaurants may join a trade association at one level but not at another level, depending on which level best serves their needs.

The trade associations focus on legislative advocacy around labor force issues and training (since industry turnover is high). Although there is substantial employee training in food safety (to prevent illnesses from contaminated food), there is somewhat less interest in OSH training in this high-turnover industry. Local trade associations frequently function more as an interface between businesses and their customers, offering dining guides and tasting events. Through reference by a workers’ compensation organization, NIOSH selected a state-level trade association as a target intermediary.

The trade association already had a substantial effort underway in OSH training for member businesses, most of which are small, because they are a group provider of workers’ compensation insurance. Members who purchase coverage through the association get medical management and OSH prevention services along with insurance coverage. OSH services included consultations and training. After observing training sessions offered by the association, NIOSH joined their employee safety advisory committee. It was made up of representatives from medical care, OSH services, and workers’ compensation insurance providers. NIOSH joined with the objective of assessing the association’s state-wide training operation and potential of other partnering organizations as intermediaries.

Over a three year period, NIOSH participated in bi-annual OSH advisory committee meetings. It suggested curriculum and training evaluation changes. The advisory committee was receptive and contributed many other ideas for content and improved training methods. These intermediaries were experienced at listening to restaurant employers’ OSH training and information needs through training session evaluations and interactions on specific injury cases. They knew employers were concerned about insurance costs, employee safety behaviors, workplace violence, and cut and burn injuries, but also knew employers wanted fresh content at every session they attended.

7.2. Intermediary–small business phase

While NIOSH was participating on the advisory committee, 12 training sessions were offered by the association to employers. Sessions were offered by webinar and face-to-face events, and were promoted to trade association members (approximately 2400 firms with 5000 locations) as a means to learn how to control costs while meeting training requirements needed to qualify for a discount on workers compensation insurance premiums. NIOSH contributed presentations in hazard mapping and safety climate development. The hazard mapping content was similar to that used in case 3 above, but specific to physical hazards present in most restaurants. The safety climate development content was focused on identifying manager behaviors that contribute to a safe work environment and methods to support those management behaviors.

These contributions introduced content and training methods that were adopted by the association in written training materials used for other classes. The association adopted the new content based on evaluation results from their members. Although extensive evaluation data were not collected for every event, according to post-event attendee questionnaire results, reactions by trainees were mostly positive, with many participants citing the hazard mapping portion as particularly valuable to their business. For example, following one webinar more than half the attendees reported that they found the hazard mapping presentation to be of high quality (16 of 29 respondents indicated good or very good), while following another presentation the majority of attendees noted hazard mapping could be a useful injury prevention tool in his/her operation (56 of 68 respondents agreed or strongly agreed).

7.3. Lessons learned

NIOSH learned the association was already an advanced provider of OSH services. The association had an obligation to train employers in OSH as a purveyor of workers’ compensation group insurance. Their OSH prevention services and medical case management providers were also experienced and sophisticated in OSH matters in restaurants. They were supported by a portion of the workers’ compensation premiums paid by group members. There was little room for these organizations to grow in their understanding of and commitment to OSH for restaurants. For this reason, NIOSH likely learned less about what might motivate trade associations than it might have in other situations.

Nevertheless, NIOSH introduced these intermediaries to new content areas and evaluation methods they adopted. NIOSH learned these intermediaries recognized the difficulty of serving employers in smaller restaurants, and were motivated to reach these employers with services. The association also recognized provision of workers’ compensation group coverage is unusual for restaurant trade associations. The trade association is actively engaged in conveying information about their OSH programs to other associations that serve this industry through an association networking organization. Through this experience, NIOSH learned an initiator need not always initiate positive OSH change, but sometimes has to learn it is already happening.

This case also demonstrates that the initiator may only be taking on the role of adding or improving OSH offerings to what intermediaries are already offering SBs, and not acting as the initiator of the entire SB intervention effort. The trade association not only acted in the role of intermediary, but also in that of the initiator. They identified other intermediaries including medical care, OSH services, and workers’ compensation insurance providers and assembled them for the purpose of providing external OSH assistance to employers. Additionally, in this case NIOSH might also be described as taking on the role of an opinion leader within the group of intermediaries assembled by the trade association as it was able to influence the group to add new programming elements. Thus, the roles of initiator and intermediary can become blurred depending on the context.

8. Discussion

The cases described here demonstrate the application of a model for delivering OSH to smaller businesses. In each of the cases described, the initiator was able to reach SBs with some form of OSH-related information and/or assistance. However, the cases varied in the degree to which intermediaries successfully engaged SBs with new or additional OSH services, and in how intermediaries sustained engagement with SBs beyond the demonstration activities.

8.1. Common elements of success

The sustained success of a new or improved OSH engagement effort for an intermediary organization depends very much upon the presence of potential champions for OSH as well as supportive opinion leaders. Intermediaries are more likely to engage SBs with new or more OSH assistance when one or more opinion leaders voice support for such an effort. However, sustainability of such an effort also depends on champions, or individuals within intermediaries taking a leadership role in planning and delivering OSH assistance to SBs. Sustainability is also more likely if OSH is within the remit of intermediary leaders. Without leadership at the intermediary level, the initiator remains the champion of the effort and potential for sustained impact is reduced.

Initiators must monitor the SB OSH activities of intermediaries to detect such decisions and ensuing activities. They must do so because if their diffusion efforts are truly successful, the intermediaries will consider the decision to do more in OSH to have been a largely internal decision, and will not think to advise the initiator. Additionally, initiators must know the outcomes of the intermediary–small business interaction to inform efforts with intermediaries in other regions/industries.

Much of the activity of the initiator is focused on taking an active and participatory role in the community of interest. Members of the initiator organization may need to embed themselves within the intermediary organization to most effectively persuade them to offer more OSH resources and assistance by becoming a member, serving on a committee, or offering service to the organization. Indeed, NIOSH has found that by offering to provide assistance with presenting on various OSH topics, evaluation, or needs assessment, or by participating in committees it has been able to leverage contributions to an exchange which has been reciprocated by intermediaries’ willingness to try new outreach activities and explore partnerships with other intermediaries for SB OSH.

Intermediaries are more easily persuaded to offer OSH assistance that they know SBs want. While there are opportunities for initiators to influence programming decisions, the perspectives of intermediary organization members or clients are the most important determinant of the intermediary’s actions. Often employers’ concerns are driven by OSH-related issues in the news (e.g., new OSH legislation, disaster preparedness, or pandemic disease). But more basic topics were also selected for programming (e.g., fall prevention, hazard recognition) especially when there was some effort to assess the OSH needs of the members or clients.

An evaluation of a trial demonstration can be very useful for convincing intermediaries of the value-added by engaging SBs with OSH programming. The evaluation NIOSH conducted for the trenching safety class helped to highlight for the intermediaries how SBs valued their collaborative efforts. This not only led them to replicate their cooperation in engaging SBs, but also to modify their approach to include more on-site demonstration in their training. Although NIOSH did not have the opportunity to evaluate the envisioned training with boatyard contractors, preliminary data collection functioned as a needs assessment which did influence the intermediaries to offer more and/or different OSH assistance to SBs in their networks.

8.2. Common challenges

When not physically proximal to the intermediaries or the region where the targeted SB audience is located, there is a lack of in-person meeting opportunities. Such opportunities are critical for presenting the value of OSH engagement and offering assistance with developing plans for engaging SBs, or the business side of the initiator–intermediary exchange. These opportunities are also important for maintaining a good working relationship, or the social side of the exchange. As the communications between initiator and intermediary become less formal, there is a greater likelihood of cooperation between parties because there is not only a professional exchange but an interpersonal one as well, and that can have an additive effect for reciprocation. The authors developed stronger interpersonal relationships with the intermediaries in the trenching and OSH workshop cases than those in the restaurant and boatyard cases, and with better relationships, they were more likely to try new things.

A lack of resources can also be a barrier to action not only among SBs, but also among intermediaries and initiators. Limited staffing for intermediaries and initiators can make it difficult for either party to devote enough time to engage one another for developing SB OSH assistance plans. Limited OSH expertise internal to the intermediary organization or available in the geographic area was a barrier to sustainability of the OSH assistance presented in case 2, and limited travel resources limited the initiator’s ability to engage intermediaries in case 4. It is possible that merely interacting with a government agency devoted to OSH could cause an intermediary to take action for offering increased or new OSH service to the SBs they serve. A breakdown in the relationship between the initiator and intermediary could lead the initiator to miss the delivery of OSH from the intermediary to SBs.

It is important to balance the exchange between initiator and intermediary so that the relationship does not simply become a direct channel between initiator and SB targets. The intermediary–small business relationship is less likely to be sustained if there is not a balanced exchange established between them before the initiator discontinues engagement with the intermediaries. In some cases NIOSH assumed a leadership role without any clear transition to an intermediary taking ownership of the efforts to engage SBs. NIOSH has also over-contributed to the exchange with intermediaries by providing service in the way of new programming, needs assessment, or evaluation assistance without the intermediary reciprocating by taking on new and/or improved engagement with SBs independent of NIOSH leadership or prompting. It is important to emphasize the objectives for intermediaries’ engagement with SBs and not to overcommit the initiator’s resources to any particular demonstration effort. The focus for the initiator must remain on the broader impact potential of the model and not only the successful implementation in an individual case, which can be difficult to do given the social exchange which occurs during the process.

It is worth noting that the concept of what a small business is varies among intermediaries and initiators. NIOSH has not endorsed a specific definition based on number of employees, and the introduction above references the predominance of firms with 20 or fewer employees across sectors. The case studies presented here were focused on firms with less than 50 employees, and this was due in part to the perspective of the intermediaries involved in each case. That is, some intermediaries may consider a SB to be one with fewer than 100 employees, while others may consider 20 or fewer to be small. There are likely significant differences in how a business with 15 employees and one with 45 employees operates. The need for clarity on how small business is defined is important for practical purposes in communication between initiators and intermediaries, as well as for better understanding among the research community (for a detailed discussion, see Cunningham et al., in press).

There is also a limitation in the initiator also serving the role of evaluator. In the role of initiator, an organization may be inclined to assume it well suited for creating positive OSH changes by engaging intermediaries who will in turn provide OSH assistance to SBs. It is likely in some cases (such as cases 3 and 4) that the role of the initiator need not be one of leadership, but rather one of monitoring or observing. The application of the model would likely be better evaluated with an analysis of the intervention conducted by the intermediaries or by another observer such as an academic consultant. An external evaluation by a consultant may also provide more accurate feedback from intermediaries regarding the role of the initiator. In the cases described above, the initiator did attempt to teach intermediaries how to better evaluate OSH assistance efforts as in each case existing evaluation strategies were minimal or non-existent. However, this was not a primary focus of communication between initiator and intermediaries and may suggest an added component to a future revised model.

8.3. Directions for future research

Given that research focused on the social systems level for SB OSH intervention is rather limited, the opportunities for future research are plentiful and a few possibilities are offered here. With particular attention to the study of intermediaries within the model, initiators should focus on identifying the characteristics of OSH champions and opinion leaders. What organizations do these individuals belong to? How does that vary across industries? Social networking data is critical to understanding how to reach intermediaries and SBs with OSH. Who listens to whom, and why? How large are business to business networks by geography? What kinds of appeals will most effectively nurture an exchange which will lead to new or more OSH assistance for smaller businesses? For example, it may be fruitful for initiators to focus on developing messages that expand the perceived connection between risk management assistance and return on investment. And what communications channels can support inter-personal communications to help reach intermediary organizations? These issues also demand attention at the intermediary–small business phase of the model. However, from the initiator perspective there is perhaps a more immediate need to focus on better understanding intermediaries because of the enormous potential for meaningfully impacting SB OSH.

The lessons learned from these cases also suggest the possibility of a revised model, with decision nodes included at each step to inform whether the initiator should proceed, and in what way. For example, the lessons from cases 3 and 4 suggest the initiator may not need to play a central and/or visible role in the OSH assistance process and might be of better service in an observer role. Such a decision might be addressed at step 3 of the model where the initiator selects strategies for engaging intermediaries. Furthermore, as seen in case 4 the roles of initiator and intermediary may become blurred when an initiator engages an intermediary that is already strongly engaging SBs in OSH assistance. There might also be a decision node where the roles of initiator and intermediary could be shifted, as a typical initiator such as NIOSH may also directly intervene with SBs as an intermediary under the leadership of another organization. Additionally, a revised model might include more detailed plan for selecting sectors or groups to target. Part of step 1 might include rationale for target group selection, including both SB sector and intermediary selections. Based on the cases presented here, the rationale for intermediary selection should include an assessment of opinion leadership within the organization as it relates to SB OSH.

A particular intermediary worth focusing on is workers’ compensation insurance providers. Few intermediaries are so clearly connected to the OSH activities and finances of SBs. A main driver for seeking OSH assistance is the availability of workers’ compensation premium insurance discounts. For example, legislation in Massachusetts stipulates a company can receive a 15% discount by purchasing the services of a qualified loss manager (Spurlock and Wertz, 2008). However, the availability of incentives and loss control assistance vary greatly across states. Further attention should be focused on workers’ compensation loss control assistance and policies which are associated with greater OSH activity and reduced injury and illness outcomes among smaller firms.

There is a continued need for intervention research from a diffusion perspective. That is, data are needed on the adoptability of effective OSH interventions by SBs. This includes measuring complexity, trialability, cost, compatibility, etc. and then finding or adapting a selection of interventions that maximize adoptability. It may be useful to measure the time it takes for the intermediary community and the SB community to move through stages of change or other models of individual change as they relate to SB OSH assistance. Under what conditions is adoption quicker or slower? And which conditions support sustainability of interventions? There may also be particular combinations of intermediaries across and within industries which are more amenable to collaborating for SB OSH purposes.

9. Conclusion

Public health and other initiator organizations do not have the capacity to adequately assist small businesses with OSH. Initiators must depend on intermediaries who have compatible interests in smaller businesses. Partnering with such organizations brings a number of practical challenges, but those partnerships are the most promising approach for helping smaller firms and their workers who are most in need of sustainable OSH assistance.

Overall the extended model for SB OSH intervention provides a useful framework for understanding the roles of initiators and intermediaries. SB OSH assistance is likely to be sustained when the initiator identifies the right fit between intermediaries to address the needs of SBs in a given area. The model provides an approach for initiators to engage intermediaries that takes into account their strengths and builds on them to enhance their potential for impacting SB OSH. Clearly there are points for refinement within each of the specific steps of the model which would help to develop a more prescriptive approach. Yet with its focus on the small business social system, and supported by the authors’ experiences working with intermediary organizations, the model offers some encouragement that the problem of inadequate OSH assistance for smaller businesses might be reduced.

Table 2.

Summary of fall prevention and respirator training for boat repair contractors case study.

| SB OSH model steps | |

| Intervention |

|

| Initiator–intermediary phase | |

| 1. Analyze characteristics of SBs and potential intermediaries |

|

| 2. Analyze ways that intermediaries perceive provision of OSH info. and services to SBs |

|

| 3. Develop messages and select channels for reaching intermediaries |

|

| 4. Engage intermediaries using selected strategies |

|

| Intermediary–small business phase | |

| 5. Analyze ways that SBs perceive OSH |

|

| 6. Develop messages and select channels for reaching SBs |

|

| 7. Engage SBs using selected strategies |

|

| 8. SBs engage in workplace prevention activities |

|

| Lessons learned |

|

Table 3.

Summary of basic compliance and hazard recognition for general industry case study.

| SB OSH model steps | |

| Intervention |

|

| Initiator–intermediary phase | |

| 1. Analyze characteristics of SBs and potential intermediaries |

|

| 2. Analyze ways that intermediaries perceive provision of OSH info. and services to SBs |

|

| 3. Develop messages and select channels for reaching intermediaries |

|

| 4. Engage intermediaries using selected strategies |

|

| Intermediary–small business phase | |

| 5. Analyze ways that SBs perceive OSH |

|

| 6. Develop messages and select channels for reaching SBs |

|

| 7. Engage SBs using selected strategies |

|

| 8. SBs engage in workplace prevention activities |

|

| Lessons learned |

|

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

References

- Antonelli A, Baker M, McMahon A, Wright M. Six SME Case Studies that Demonstrate the Business Benefit of Effective Management of Occupational Health and Safety. [accessed 16.04.13];Health and Safety Executive, RR504, Suffolk. 2006 < http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr504.pdf>.

- Breslin FC, Kyle N, Bigelow P, Irvin E, Morassaei S, MacEachen E, Mahood Q, Couban R, Shannon H, Amick BC. Effectiveness of health and safety in small enterprises: a systematic review of quantitative evaluations of interventions. J Occup Rehabil. 2010:163–179. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Ballew P, Dieffenderfer B, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, Kreuter MW, Myers BA. Evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity: what contributes to dissemination by state health departments. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:S66–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011. quiz S74–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley JP, Sestito JP, Hunting KL. Fatalities in the landscape and horticultural services industry, 1992–2001. Am J Ind Med. 2008;51:701–713. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Construction Research and Training [CPWR] The Construction Chart Book: The US Construction Industry and Its Workers. 4. Silver Spring, MD: CPWR; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cragun DL, DeBate RD, Severson HH, Shaw T, Christiansen S, Koerber A, Tomar SL, Brown KM, Tedesco LA, Hendricson WD. Developing and pretesting case studies in dental and dental hygiene education: using the diffusion of innovations model. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:590–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TR, Sinclair R, Schulte P. Better understanding the small business construct to advance research on delivering workplace health and safety. Small Enterprise Res in press. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, Meyer G. An exploratory tool for predicting adoption decisions. Sci Commun. 1994;16:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dugdill L, Kavanagh C, Barlow J, Nevin I, Platt G. The development and uptake of health and safety interventions aimed at small businesses. Health Educ J. 2000;59:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Eakin JM, Champoux D, MacEachen E. Health and safety in small workplaces: refocusing upstream. Can J Public Health. 2010;101 (Suppl 1):S29–S33. doi: 10.1007/BF03403843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano B, Curro F, Pastorino R. A study of the relationship between occupational injuries and firm size and type in the Italian industry. Saf Sci. 2004:587–600. [Google Scholar]

- Fenn P, Ashby S. Workplace risk, establishment size and union density. Brit J Ind Relat. 2004:461–480. [Google Scholar]

- Filiaggi AJ, Courtney TK. Restaurant hazards. Profession Saf. 2003;271:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Greiver M, Barnsley J, Glazier RH, Moineddin R, Harvey BJ. Implementation of electronic medical records: theory-informed qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e390–e397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Limborg HJ. A review of the literature on preventive occupational health and safety activities in small enterprises. Ind Health. 2006;44:6–12. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Bager B, Granerud L. Small enterprises – accountants as occupational health and safety intermediaries. Saf Sci. 2010;48:404–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Kvorning LV, Rasmussen CD, Smith LH, Flyvholm MA. A model for design of tailored working environment intervention programmes for small enterprises. Saf Health Work. 2012;3:181–191. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2012.3.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headd B. An Analysis of Small Business and Jobs. Small Business Administration; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hinze JW, Gambatese JA. Factors that influence the Safety Performance of Specialty Contractors. J Construct Eng Manag ASCE. 2003;129:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong BY. Occupational deaths and injuries in the construction industry. Appl Ergon. 1998:335–360. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird I. Using small business characteristics to maximize health and safety. Proceedings of the Understanding Small Enterprise 2013 Conference; Nelson, New Zealand. 2013. [accessed 23.04.13]. < http://www.useconference.com/images/custom/laird_-_abstract.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Legg S, Battisti M, Harris LA, Laird I, Lamm F, Massey C, Olsen K. National Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Committee (NOHSAC) Technical Report. Vol. 12. Wellington, New Zealand: 2009. [accessed 10.06.14]. Occupational Health and Safety in Small Businesses. < http://www.dol.govt.nz/publications/nohsac/pdfs/technical-report-12.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Mendeloff JM, Nelson C, Ko K, Haviland A. Small Businesses and Workplace Fatality Risks. RAND Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. Communication Theories. McGraw Hill; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morse T, Dillon C, Weber J, Warren N, Bruneau H, Fu R. Prevalence and reporting of occupational illness by company size: population trends and regulatory implications. Am J Ind Med. 2004;45:361–370. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun A, Lentz TJ, Schulte P, Stayner L. Identifying high-risk small business industries for occupational safety and health interventions. Am J Ind Med. 2001:301–311. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200103)39:3<301::aid-ajim1018>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen K, Legg S, Hasle P. How to use programme theory to evaluate the effectiveness of schemes designed to improve the work environment in small businesses. Work (Reading, Mass) 2012;41:5999–6006. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0036-5999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page K. Blood on the coal: the effect of organizational size and differentiation on coal mine accidents. J Saf Res. 2009:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa HG, Self JT, Njite D, King T. Why restaurants fail. Cornell Hotel Restaur Admin Quart. 2005;46 (3):204–322. [Google Scholar]

- Pombo-Romero J, Varela LM, Ricoy CJ. Diffusion of innovations in social interaction systems. An agent-based model for the introduction of new drugs in markets. Eur J Health Econ. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5. Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte P, Okun A, Stephenson CM, Colligan M, Ahlers H, Gjessing C, Loos G, Niemeier RW, Sweeney MH. Information dissemination and use: critical components in occupational safety and health. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44 (5):515–531. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair R, Cunningham TR. Predictors of safety activities in small firms. Saf Sci. 2014;64:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair R, Cunningham TR, Schulte P. A model for occupational safety and health intervention in small businesses. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56 (12):1442–1451. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokas RK, Emile J, Nickels L, Gao W, Gittleman JL. An intervention effectiveness study of hazard awareness training in the construction building trades. Public Health Rep. 2009;124 (Suppl 1):160–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurlock BS, Wertz KR. Chomp Comp: The Small Business Guide to Lower Workers’ Comp Premiums. Lighted Path Publishers; Louisville, KY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. [accessed 25.04.13];Occupational Illnesses and Injuries. 2010 < http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/ostb2813.txt>.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau. [accessed 14.04.14];Statistics of US Businesses. 2011 < http://www.census.gov/econ/susb/>.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. [accessed 28.02.10];Compliance Assistance Quick Start: General Industry. 2010 < https://www.osha.gov/dcsp/compliance_assistance/quickstarts/general_industry/index_gi.html>.

- Vossen RW. Relative strengths and weaknesses of small firms in innovation. Int Small Bus J. 1998;16:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Welbourne J, Booth-Butterfield S. Using the theory of planned behavior and a stage model of persuasion to evaluate a safety message for firefighters. Health Commun. 2005;18 (2):141–154. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]