Abstract

PROSTVAC immunotherapy is a heterologous prime-boost regimen of two different recombinant pox-virus vectors; vaccinia as the primary immunotherapy, followed by boosters employing fowlpox, to provoke immune responses against prostate-specific antigen. Both vectors contain transgenes for prostate-specific antigen and a triad of T-cell costimulatory molecules (TRICOM). In a placebo-controlled Phase II trial of men with minimally symptomatic, chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, PROSTVAC was well tolerated and associated with a 44% reduction in death. With a novel mechanism of action, and excellent tolerability, PROSTVAC has the potential to dramatically alter the treatment landscape of prostate cancer, not only as a monotherapy, but also in combination with other novel agents, such as immune check point inhibitors and novel androgen receptor blockers. A Phase III trial recently completed accrual.

Keywords: pox virus immunotherapy, prostate cancer, PROSTVAC

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among men [1]. Targeting gonadal androgen synthesis is the corner stone of treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. However, responses are not durable and almost all men develop castrate-resistant disease [2]. Until 2010, Docetaxel-based chemotherapy was the only systemic regimen known to extend survival in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) [3,4]. Since then, the approval of novel agents has rapidly changed the treatment landscape of mCRPC. The regulatory approval of sipuleucel-T for mCRPC validated immune modulation as an effective strategy in prostate cancer. Additionally, an androgen synthesis inhibitor (abiraterone acetate), a novel androgen receptor inhibitor (enzalutamide), a novel taxane (cabazitaxel) and an α emitting radiopharmaceutical (radium-223), have been approved. However, these agents provide only a modest improvement in median survival of 3–5 months each. Newer therapies without overlapping mechanisms of action and toxicities are needed to further improve the survival outcome.

Across the field of oncology, immunotherapeutic agents have garnered a great deal of interest. Prostate cancer provides an optimal setting for immunotherapy for many reasons [5]. First, prostate cancer cells express a number of tumor-associated antigens that can serve as targets for immunotherapy. Furthermore, because of the expendable nature of the prostate as an organ, a prostate-specific immune response is well tolerated. Finally, the prostate provides a reliable tumor marker (prostate-specific antigen [PSA]) which allows employment of immunotherapy in the presence of minimal residual disease, when the immunosuppressive effects of the tumor are relatively milder.

Overview of the market

Sipuleucel-T (Provenge®, Dendreon Corp., WA, USA), an approved agent for the treatment of mCRPC, consists of autologous antigen-presenting cells (APCs) enriched for a CD54+ dendritic cell fraction, harvested by leukopheresis and cultured with a fusion protein (PA2024) comprising prostate acid phosphatase (PAP) and granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [6].

In a Phase III trial, 512 men with asymptomatic chemotherapy-naive mCRPC, were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to sipuleucel-T (n = 341) or placebo (n = 171). The primary and secondary end points were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively. The median OS was significantly improved in the sipuleucel-T group, when compared with placebo group (25.8 vs 21.7 months; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.77; p = 0.02), with a relative reduction of 22% in the risk of death in the sipuleucel-T group. Despite an improvement in OS, response rates and PFS were similar in the two study groups. This may be attributed to the time delay in the translation of immunologic effects to clinically measurable antitumor effects seen with immunotherapy, resulting in initial progression followed by delayed reduction of tumor growth. The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate and included chills, fever, fatigue, nausea and headache.

In an exploratory analysis, significance of baseline PSA as a predictor of treatment response was examined [7]. Baseline PSA (in ng/ml) was divided in to quartiles (≤22.1, >22.1 to 50.1, 50.1–134.1 and >134.1), and consistency of response within each quartiles was assessed. The greatest magnitude of benefit with sipuleucel-T was observed in patients in the lowest PSA quartile, where median OS for sipuleucel-T versus control was 41.3 vs 28.3 months (HR: 0.51 [95% CI: 0.31–0.85]), resulting in a 13.0-month improvement in OS. In contrast, the median OS for sipuleucel-T vs control in the highest PSA quartile was 18.4 vs 15.6 months (HR: 0.84 [95% CI: 0.55–1.29]), resulting in a 2.8-month improvement in OS. In general, sipuleucel-T therapy was effective in all patient subgroups evaluated, with a trend toward a superior outcome in patients with baseline prognostic features indicative of less advanced disease, thus providing a rationale for the administration of sipuleucel-T as early as possible.

Ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company), an immune check point inhibitor, is in the advanced phases of development for the treatment of mCRPC. Ipilimumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to the CTLA-4 [8]. In normal circumstances, CTLA-4 prevents T-cell activation via its binding with B7 ligand on APCs, and thus helps maintain immune tolerance to self-antigens. By preventing the interaction of CTLA-4 and B7 ligand, ipilimumab leads to enhanced T-cell activation, proliferation and an improved anti-tumor immune response. Notably, ipilimumab leads to a generalized upregulation of the host immune system against a diverse group of antigens including tumor and self antigens, unlike more specific immunotherapies such as sipuleucel-T and PROSTVAC, where specific tumor-associated antigens are targeted by the immune system [9].

Of the two large placebo-controlled Phase III trials of ipilimumab which have completed accrual, one in chemo-naive and a second in postdocetaxel mCRPC patients, the results of the trial in the in the post docetaxel mCRPC setting were recently reported [10]. Men with mCRPC were randomized in 1:1 fashion to receive bone-directed radiotherapy at 8 Gy prior to either 10 mg/kg ipilimumab (n = 399) or placebo (n = 400) every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by maintenance therapy with one dose every 3 months in men with nonprogressive disease. The primary end point was overall survival. The secondary end points included progression free survival, pain response and safety profile. A total of 799 men were include in the intent-to-treat analysis. There was no improvement in median overall survival with ipilimumab compared with placebo (11.2 vs 10 months; HR: 0.85; p = 0.053). However, there was a modest improvement in median progression free survival with ipilimumab over placebo (4.0 vs 3.1 months, respectively; HR 0.70, p < 0.0001). Additionally, there were more PSA declines ≥50% with ipilimumab than placebo (13.1 vs 5.3%). Use of post-trial cancer therapy was similar in the ipilimumab and placebo arms (41.0 vs 46.7%). Notably, as per prespecified subgroup analyses, ipilimumab was more effective in men with favorable baseline prognostic factors (i.e., no visceral metastases, alkaline phosphatase <1.5 × ULN and hemoglobin ≥11 g/dl). In this subset of men with relatively low volume disease, median overall survival was 22.7 months (95% CI: 17.8–28.3) for ipilimumab (n = 146) compared with 15.8 months (95% CI: 13.7–19.4) for placebo (n = 142); HR: 0.62.

Consistent with the prior experience of ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma, the most common drug-related adverse events in men with prostate cancer were immune related. Given superior efficacy data of ipilimumab in men with more favorable baseline prognostic factors in this post docetaxel mCRPC setting, results of the ongoing Phase III trial of ipilimumab in the prechemotherapy mCRPC setting are anxiously awaited.

PROSTVAC

PROSTVAC immunotherapy regimen is comprised of a recombinant vaccinia vector as the primary immunotherapy, followed by multiple boosters employing a recombinant fowlpox vector, utilizing a heterologous prime boost strategy. Both vectors contain transgenes for PSA and TRICOM. TRICOM consists of costimulatory molecules, including ICAM-1 (CD54), B7.1 (CD80) and LFA-3 (CD58).

Mechanism of action of PROSTVAC

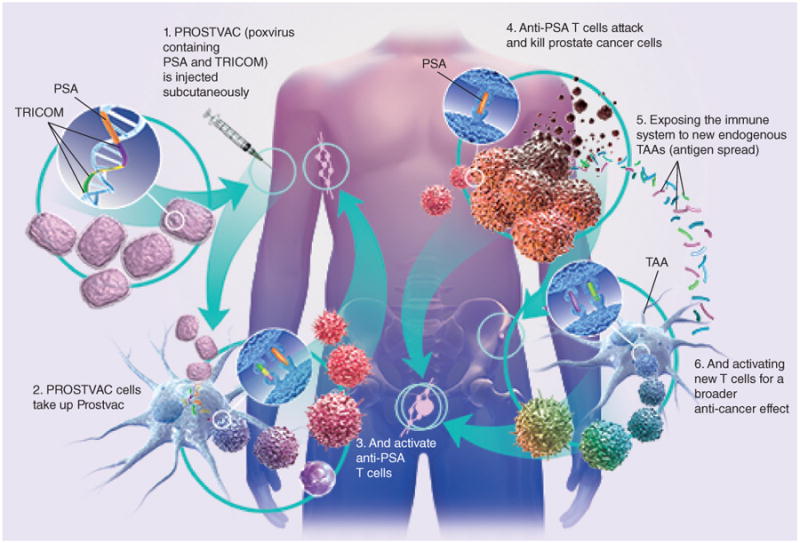

The poxvirus family is composed of dsDNA viruses that do not integrate with the host cell genome, and instead replicate within the cytoplasm of infected cells. Following the subcutaneous injection and the subsequent uptake of PROSTVAC by the dendritic cells, the inherent immunogenicity of the pox virus leads to a strong immune response directed against the viral protein, including the encoded tumor antigen, PSA. The resulting anti-PSA cytotoxic T cells attack and kill prostate cancer cells, exposing the immune system to a wide array of new endogenous tumor associated antigens, and subsequently activating new T cells for a broader anticancer effect, a phenomenon known as antigen spreading (Figure 1) [11,12].

Figure 1. PROSTVAC mechanism of action.

PSA: Prostate-specific antigen; TAA: Tumor-associated antigen; TRICOM: Triad of T-cell costimulatory molecules.

Figure was provided by Bavarian Nordic, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA.

A major limitation of vaccinia virus based vectors is the rapid appearance of strong neutralizing antibodies against the vaccinia virus. This renders a booster immunization using the same virus (homologous prime/boost vaccination) ineffective, as the antibody response to viral proteins dominates over the intended response to encoded antigens (such as PSA) [13]. This can be circumvented by using avipox (fowl pox) viral vectors encoding the same antigens as the booster vaccination (heterologous prime/boost vaccination). The avipox virus is a family of pox viruses that infects birds, and does not replicate in mammalian cells. Since infection of mammalian cells with avipox viruses do not lead to appearance of neutralizing antibodies, avipox viral particles persist for a longer period of time to express foreign transgenes, resulting in a significantly enhanced T-cell immunity.

Optimal T-cell stimulation by PROSTVAC is mediated through two signals: one delivered via engagement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and the other provided by costimulatory ligands B7-1, ICAM-1 and LFA-3. In absence of costimulation, Human T helper cells respond marginally or even exhibit anergy to a weak antigen [14]. It has been shown that T-cell activation using vectors containing three costimulatory molecules is far greater than the sum of three independent constructs, each containing one costimulatory molecule [14,15]. This triad of costimulatory molecules employed in PROSTVAC is known as TRICOM. Another important aspect of the immune response generated by PROSTVAC is that it provokes a cellular immune response and not a humoral response. Thus, immunotherapy with PROSTVAC does not elicit an anti-PSA antibody response.

Clinical efficacy

Phase I/II studies of PROSTVAC in prostate cancer

A Phase I trial of recombinant vaccinia PSA (rV-PSA) in patients with mCRPC was conducted at the National Institute of Health. The trial enrolled 42 patients who received up to three monthly injections of rV-PSA. The primary objective was to determine the safety of pox virus immunotherapy. There was no significant treatment related toxicity. Immunological studies showed an increase in the proportion of PSA-specific T-cells capable of lysing PSA-expressing tumor cells in vitro in a subset of patients [16].

Subsequent to this study, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) conducted a study to evaluate the feasibility and tolerability of a prime/boost immunotherapeutic strategy using vaccinia virus and fowlpox virus expressing human PSA (rV-PSA and rF-PSA, respectively) in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer with biochemical progression after definitive local therapy. A total of 64 men were randomized to one of the three following treatment arms: four injections with rF-PSA (arm-A); three injections of rF-PSA, followed by one rVPSA injection (arm-B) or one injection of rV-PSA injection, followed by three injections of rF-PSA (arm-C) [17]. The primary end point was PSA response at 6 months. The study was designed to distinguish a 30% PSA progression-free rate at 6 months from a 5% rate. There were minimal toxicities with the prime/boost schedule. Of the eligible patients, ∼45% did not have PSA progression at 19.1 months and the median time to clinical progression was not reached. There was a trend favoring the treatment group that received a priming dose of rV-PSA, in other words, subjects randomized to arm-C [15]. These results led to several studies to establish the safety and efficacy of poxvirus expressing PSA or individual T-cell costimulatory molecules in separate clinical trials [17,18]. Eventually, a Phase I clinical trial was conducted where both PSA and all three costimulatory molecules (TRICOM) were used in a single vector [19]. Ten men with CRPC were treated with rV-PSA/TRICOM, followed by a single dose of rF-PSA/TRICOM without any grade 3 or 4 adverse events, thus demonstrating that immunotherapy with rV and rF combined with PSA and TRICOM to be well tolerated. The most common side effects were injection site reactions and fatigue [16].

Another Phase I trial evaluated the safety of combination granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and immunotherapy with recombinant vaccinia virus (prime) and recombinant fowlpox virus (boost). Fifteen men with mCRPC cancer were enrolled and treated with rF-PSA/TRICOM alone or rV-PSA/TRICOM, followed by rF-PSA/TRICOM on a prime and boost schedule with or without recombinant-granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor protein (GM-CSF) or recombinant fowlpox-granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor vector (rF-GM-CSF). Grade 2 toxicities were observed in patients who received higher doses of rF-GM-CSF, but there were no toxicities exceeding grade 2. Two men who received a vaccinia prime and monthly fowlpox boost along with r-GM-CSF, mounted greater than twofold increase in PSA-specific T-cell precursors after 3 monthly vaccinations. Four of six men who were HLA-A2+ elicited PSA-specific immune response, and nine of 15 men had decreases in serum PSA velocity. None of the men had measurable responses using RECIST criteria. Overall, the combination was observed to be safe and Phase II testing was recommended [20].

Based on these results, a randomized, Phase II study was initiated in men with mCRPC. Thirty-two men with mCRPC were randomized to one of the following four cohorts defined by the adjuvant immunotherapy received: no adjuvant immunotherapy (cohort I), recombinant human GM-CSF protein (cohort II), 107 plaque-forming units (PFUs) rF-GM-CSF (human; cohort III), or 108 PFU rF-GM-CSF (human; cohort IV). All men received rV-PSA – TRICOM as primer immunotherapy, followed by monthly boosters of rF-PSA-TRICOM with the respective immune adjuvant, as defined by the designated cohort, until disease progression. The primary end point was immune response as evaluated by ELISPOT assay and secondary objectives included PFS and OS. There was no difference in PSA-specific T-cell responses among any of the four cohorts. The median OS was 26.6 months compared with median predicted OS by Halabi nomogram of 17.4 months [21]. Men with greater PSA-specific T-cell responses showed a trend (p = 0.055) toward enhanced survival.

These encouraging results from early phase studies led to a larger placebo-controlled Phase II trial, with men with minimally symptomatic, chemotherapy-naive mCRPC (n = 122) who were randomized to receive PROSTVAC and local GM-CSF, or empty vectors plus saline injections [6]. Therapy was well tolerated. Although, there was no difference in PFS, median OS was significantly improved (25.1 vs 16.6 months, estimated HR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.37–0.85, p = 0.0061). PROSTVAC immunotherapy was well tolerated and associated with a 44% reduction in the death rate.

PROSTVAC in combination with immune check point inhibitors

Ipilimumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that inhibits CTLA-4, a negative coregulatory molecule expressed on T cells, thus leading to a nonspecific generalized upregulation of immune response [10]. The rationale for a combinatorial or sequential regimen of PROSTVAC and ipilimumab is to generate a prostate cancer specific T-cell response through PROSTVAC followed by augmentation of this immune response with the use of ipilimumab.

A combination regimen was tested in a Phase I dose-escalation trial, where 30 men with mCRPC were treated with monthly doses of ipilimumab (1, 3, 5 or 10 mg/kg given on day 15 of each cycle) in combination with rV-PSA – TRICOM as primer immunotherapy, followed by monthly boosters of rF-PSA-TRICOM [22]. The predicted median OS of the overall cohort by the Halabi nomo-gram was 18.5 months. The majority of men were chemotherapy naive (n = 24). No dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) were noted and the 10 mg/kg cohort was expanded to a total of 15 men. Grade 3 or 4 immune-related adverse events were reported in 27% of men. Among six patients with prior chemotherapy, only one had a PSA decline from baseline. Of the 24 chemotherapy-naive men, 14 (58%) had PSA declines from baseline, of which six were greater than 50%. Three of 12 patients with measurable disease had unconfirmed partial responses on CT imaging. At the time of initial report, the median PFS of the overall cohort was 3.9 months (5.9 months in chemotherapy-naive men), and the median OS was 34.4 months (not reached in chemotherapy-naive men) (Table 1). Updated survival data were presented in the 2015 Genitourinary Cancer Symposium. The observed median OS was 31.3 months for all dose cohorts and 37.2 months for men treated at 10 mg/kg. Notably, there appeared to be a tail on the survival curve with approximately 20% of men at 10 mg/kg being alive at 80 months [23].

Table 1. Reported trials of pox virus-based immunotherapy in combination with other anticancer therapies.

| Study (year) | n | Trial details | Outcomes | Safety | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madan et al. (2012) | 30 | Phase I dose-escalation trial in mCRPC patients with monthly doses of ipilimumab (1, 3, 5 or 10 mg/kg) + rV-PSA-TRICOM/rF-PSA-TRICOM | Median OS was 34.4 months (median not reached in chemotherapy-naive men); median PFS was 3.9 months (5.9 months in chemotherapy-naive patients) | No dose-limiting toxicity; grade 3–4 immune-related adverse events in 27% men, similar to those seen with ipilimumab alone | [22] |

| Gulley et al. (2005) | 30 | Phase II randomized (2:1) study with definitive radiotherapy + pox immunotherapy (priming with rV-PSA+ rV-B7.1, eight monthly boosters with rF-PSA, along with local injections of GM-CSF and low-dose IL-2 with each pox virus immunotherapy) vs radiotherapy alone in localized prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence after surgery | Threefold increase in PSA-specific T cells in 76% of men in the radiotherapy + immunotherapy arm compared with those in the radiotherapy-only arm | Well tolerated | [24] |

| Heery et al. (2013) | 44 | Phase II randomized (1:1) study with Sm-153+rV-PSA-TRICOM vs Sm-153 alone arm in men with progressive mCRPC after docetaxel therapy, with bone only metastatic disease | Median PFS was 3.7 months in the combination treatment vs 1.7 months in the Sm-153 alone | Similar hematologic toxicities in both arms, consistent with the toxicity profile of Sm-153 | [25] |

| Arlen et al. (2006) | 28 | Phase II randomized study with pox virus immunotherapy (priming with rV-PSA +rV-B7.1, boosters with rF-PSA, GM-CSF with each immunotherapy) +docetaxel or docetaxel alone in men with mCRPC | Median fold increase in PSA-specific T cells was similar in both arms (∼3.33-fold increase). Addition of docetaxel did not compromise the generation of tumor-specific T cells | Well tolerated with grade 2 or less toxicity | [26] |

| Madan et al. (2008) | 42 | Phase II randomized (1:1) trial comparing nilutamide vs immunotherapy (priming with rV-PSA+ rV-B7.1, eight monthly boosters with rF-PSA, along with local injections of GM-CSF and low-dose systemic IL-2 with each pox virus immunotherapy) in men with non-metastatic CRPC with rising PSA. Cross over allowed to receive both treatment upon PSA only progression | All men: Trend towards improved OS in men initially randomized to the immunotherapy arm (5.1 vs 3.4 years; p = 0.13) In men who were crossed over: improved OS in men receiving immunotherapy first compared with those receiving nilutamide first (6.2 vs 3.7 years; p = 0.045) | Well tolerated with grade 2 or less toxicity | [27] |

| Bilusic et al. (2011) | 26 | Phase II randomized (1:1) with flutamide alone vs flutamide + rPSA, in men with nonmetastatic CRPC with rising PSA | TTP of 85 days (56–372) in flutamide alone arm vs 223 days (70–638) in the combination arm | Not reported | [28] |

CRPC: Castration-resistant prostate cancer; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor protein; mCRPC: Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA: Prostate-specific antigen; rF: Recombinant fowlpox; rPSA: Recombinant human prostate-specific antigen; rV: Recombinant vaccinia; TRICOM: Triad of T-cell costimulatory molecules.

Another pertinent strategy may be to combine PROSTVAC with PD-1 inhibitors. Normally, the role of PD-1 is to limit autoimmunity by acting as a co-inhibitory immune checkpoint expressed on the surface of immune cells, which include T cells and the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Like ipilimumab, PD-1 inhibitors prevent T-cell anergy by interfering with protein–protein interactions at the T-cell/APC interface. Similar to the clinical trajectory of ipilimumab, the PD-1 inhibitors first demonstrated substantial activity in the setting of metastatic melanoma, with an improved safety profile. Even though PD-1 inhibitors have not been tested extensively as monotherapy in prostate cancer, a combined regimen of PROSTVAC and a PD-1 inhibitor has the potential to be a more efficacious regimen than PROSTVAC alone, given the excellent tolerability and safety profile of PD-1 inhibitors, especially in the predominantly elderly patient population of mCRPC.

PROSTVAC in combination with radiation therapy

Combining radiation to immune therapy has generated a considerable interest as a promising new modality for cancer therapeutics. Preclinical data suggest that radiation enhances immune response by upregulation of tumor antigens and expression of cell surface receptors, which can induce cell death [29–32].

A Phase II study investigated if a poxvirus encoding PSA can induce a PSA-specific T-cell response when combined with radiotherapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence after surgery. A total of 30 men were randomized in 2:1 fashion to definitive radiotherapy and pox virus immunotherapy versus radiotherapy alone. All men were required to be HLA-A2 positive. Men in the experimental arm received rV-PSA plus rV-B7.1 (priming), followed by eight monthly boosters with rF-PSA, along with local injections of GM-CSF and low-dose systemic IL-2 with each pox virus immunotherapy (Table 1). This immunotherapy regimen was safe and resulted in a threefold increase in PSA-specific T cells in 13 of 17 men on the experimental arm as compared with those in the radiotherapy alone arm. In addition to PSA-specific T-cell response, there was also evidence of de novo generation of T cells to well-described prostate antigens not encoded in the pox virus immunotherapy, thus suggesting the role of epitope or antigen spreading phenomenon in further enhancing the immune response with this strategy [24].

Another Phase II trial examined the safety and efficacy of the samarium lexidronam (Quadremet)/Sm-153) with rVF-PSA-TRICOM versus Sm-153 alone in men with progressive mCRPC with bone only metastatic disease with prior therapy with docetaxel. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate PFS at 4 months utilizing prostate cancer working group criteria. Median PFS was 3.7 months in the combination treatment arm versus 1.7 months in Sm-153 arm (p = 0.034, HR: 0.48). The trial was closed prematurely because of poor accrual but indicated synergy between rVF-PSA-TRICOM and Sm-153 [25]. Given these results, combining PROSTVAC with next generation bone seeking radioisotopes like Radium -223 is the promising next step.

PROSTVAC in combination with chemotherapy

Recent data suggest that the immune system can be activated by chemotherapy via several mechanisms including eliciting cellular responses that render tumor cell death immunogenic, transient lymphodepletion and direct or indirect stimulatory effects on immune effectors. For example, paclitaxel, cisplatin and doxorubicin have been shown in preclinical models to sensitize tumor cells to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) by making tumor cells permeable to granzyme B. This allows antigen-specific CTLs to kill not only tumor cells expressing specific antigen, but also the neighboring tumor cells that did not express those antigens [33]. Additionally, platinum-based therapy downregulates the inhibitory STAT6 and PD-L2 pathway and sensitize tumor cells for T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity [34]. Gemcitabine has been shown to induce apoptosis of established tumor cells in vivo, thereby increasing tumor antigen crosspresentation leading to priming of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [35]. Gemcitabine has also been shown to have selective detrimental effects on B lymphocytes inhibiting tumor-specific antibody production, which may skew antitumor immunity toward therapeutic T-cell responses [36].

Docetaxel, in a murine model demonstrated enhanced CD8+, but not CD4+ response, and no inhibition of Tregs. In addition, in combination with pox virus immunotherapy, docetaxel provided optimal tumor control, improved antigen-specific T-cell responses to antigens present in the pox virus, as well as to other tumor antigens not encoded in the pox virus. The combinatorial regimen was superior to either agent alone at reducing tumor burden and delaying disease progression [37].

A Phase II study sought to evaluate the immunologic effect as well as the safety and efficacy of a concurrent docetaxel (with dexamethasone) and pox virus based immunotherapy regimen in men with mCRPC (Table 1). The immunotherapy comprised priming with rV-PSA admixed with rV-B7.1, followed by boosters with rF-PSA until disease progression, and local GM-CSF injections with each immunotherapy. Twenty-eight men were randomized to receive either immunotherapy and weekly docetaxel versus immunotherapy alone. The median fold increase in PSA-specific T cells was similar in both arms (∼3.33-fold increase), following 3 months of therapy. In conclusion, docetaxel could be administered safely with pox virus immunotherapy without compromising the generation of tumor-specific T-cell responses with pox virus based immunotherapy [26].

PROSTVAC in combination with androgen ablation therapy

Androgen ablation in post pubertal mice leads to increased thymopoesis and reversal of thymic atrophy [38]. Furthermore, castration enhances immune reconstitution after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and affects not only T cells. but also thymic dendritic cells, natural killer cells and B cells [39]. A randomized study evaluated the effects of androgen ablative therapy on immune response in men with localized prostate cancer, planning to undergo surgery. Of 35 men, seven were randomized to the no-androgen ablative therapy arm, and the remaining 26 men received preoperative androgen ablative therapy for 7 (n = 7), 14 (n = 7), 21 (n = 5) or 28 (n = 7) days. Androgen ablative therapy consisted of flutamide and leuprolide acetate. Examination of prostate tissue after surgery revealed a primarily T-cell-mediated inflammatory process within the prostate, which increased with increased duration of androgen ablative therapy and without a concurrent increase in T-cell number in nonprostatic tissue, including the urethra and seminal vesicles. Furthermore, the analyses of T cells for restriction was consistent with a local oligoclonal response, suggesting a response directed against tumor antigens [40].

In a Phase II trial, efficacy of pox virus based immunotherapy in combination with anti-androgen therapy with nilutamide was studied in men with nonmetastatic CRPC with rising PSA levels (Table 1). Forty-two men were randomized to nilutamide versus pox virus based immunotherapy, and were crossed over to receive both treatments upon PSA only progression without evidence of metastatic disease. The immunotherapy regimen included priming with rV-PSA admixed with rV-B7.1, followed by monthly boosters with rF-PSA, along with local injections of GM-CSF and IL-2 with each pox virus immunotherapy. Of these 42 men, only 12 men initially randomized to the immunotherapy arm and eight men initially randomized to the nilutamide arm, could be crossed over to receive both treatments. Overall, in 42 men, there was a trend toward improved OS in men initially randomized to the immunotherapy arm (5.1 vs 3.4 years; p = 0.13). In a subgroup analysis of men who qualified to be crossed over and received both treatments, men receiving immunotherapy first had improved OS compared with those receiving nilutamide first (6.2 vs 3.7 years; p = 0.045). A subgroup of men who derived maximum benefit were those with a Gleason score <7 (p = 0.033), a baseline PSA <20 ng/dl (p = 0.013) or who had received prior radiation therapy (p = 0.018) [27]. These data suggested that men with relatively indolent prostate cancer may derive greater clinical benefit from immunotherapy alone or immunotherapy prior to second-line hormone therapy compared with hormone therapy alone or hormone therapy followed by immunotherapy.

These results have led to other Phase II studies evaluating the efficacy of PROSTVAC in combination with flutamide and the next-generation androgen receptor blocker, enzalutamide in advanced prostate cancer settings (Table 2).

Table 2. Selected ongoing clinical trials of pox virus based immunotherapy in prostate cancer.

| Patient population | Study phase | Intervention/arms | Accrual (n) | NCT Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localized prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy | II | Radical prostatectomy + neoadjuvant rV/F-PSA-TRICOM/open label, single arm | Open (27)† | NCT02153918 |

| Metastatic CRPC | II | Enzalutamide alone or with rV/F-PSA-TRICOM | Open (76)† | NCT01867333 |

| Non-metastatic castration sensitive with biochemical progression | II | Enzalutamide alone or with rV/F-PSA-TRICOM | Open (38)† | NCT01875250 |

| Localized prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance | II | rV/F-PSA-TRICOM vs Placebo | Open (150)‡ | NCT02326805 |

| Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC | III | rV/F-PSA-TRICOM + GM-CSF vs rV/F-PSA-TRICOM alone vs placebo (three arms) | Ongoing, completed accrual (>1200) | NCT01322490 |

| Non- metastatic CRPC | II | Flutamide ± rV/F-PSA-TRICOM + GM-CSF | Ongoing, completed accrual (53) | NCT00450463 |

| Metastatic CRPC | II | Docetaxel+ Prednisone ± rV/F-PSA-TRICOM | Ongoing, completed accrual (10) | NCT01145508 |

Currently recruiting.

Not open for recruitment.

CRPC: Castration-resistant prostate cancer; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor protein; mCRPC: Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA: Prostate-specific antigen; rF: Recombinant fowlpox; rV: Recombinant vaccinia; TRICOM: Triad of T-cell costimulatory molecules.

Phase III studies of PROSTVAC in prostate cancer

PROSPECT is a pivotal randomized Phase III, placebo controlled, multicenter, global trial evaluating the efficacy of PROSTVAC in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, mCRPC (Table 2). In this study over 1200 men with good performance status (ECOG 0,1), life expectancy of more than 1 year and who had no prior chemotherapy exposure, were randomized in a 1:1:1 fashion to one of three following arms: PROSTVAC plus adjuvant GM-CSF, PROSTVAC plus placebo and placebo plus placebo. Primary end point is median OS which will be evaluated in two separate comparisons; PROSTVAC plus adjuvant GM-CSF versus placebo control and PROSTVAC without GM-CSF versus placebo control. Notably, men with metastasis to organs other than bones and lymph nodes and who have had prior treatment with sipuleucel-T were excluded from the study. This study completed accrual in January 2015, and the results are expected in near future.

Safety & tolerability

PROSTVAC is generally considered safe with toxicities comprising mainly of injection site skin reactions. In the largest randomized study of PROSTVAC reported to date, most adverse events were local injection site reactions occurring in ∼60% men. Only a subset of men experienced systemic adverse events, mainly fatigue, fevers and nausea. None experience autoimmune adverse events commonly seen with the immune check point inhibitor ipilimumab. Overall, the therapy was well tolerated [6]. In a retrospective analysis of the safety of pox virus-based immunotherapy of 297 men enrolled in nine early clinical trials of pox virus immunotherapy, the adverse effect profile was very similar to those seen in the aforementioned Phase II trial. A total of 1793 injections were administered of which 33% (593) injections were associated with grade 2 or higher adverse events. The majority, 25% (454) were local injection site skin reactions. One percent of injections were associated with grade 3 adverse events, which were predominantly fatigue, nausea and fever. There were no reports of contact transmission or inadvertent inoculation [41].

Conclusion

PROSTVAC offers a novel approach to treat men with prostate cancer, which involves using a pox virus based platform to present tumor antigens, along with T-cell costimulatory molecules to the immune system, resulting in a T-cell-specific immune response against PSA. The resulting anti-PSA cytotoxic T cells attack and kill prostate cancer cells, exposing the immune system to a wide array of new endogenous tumor associated antigens, and subsequently activating newer T cells for a broader anticancer effect, a phenomenon known as epitope or antigen spreading.

In a Phase II, randomized, placebo controlled study of PROSTVAC in 125 men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic mCRPC, there was a significant improvement in OS (25.1 vs 16.6 months; HR: 0.56; p = 0.0061). This remarkable improvement in the OS was accompanied by minimal toxicities. A randomized Phase III registration trial of PROSTVAC in a similar patient population has completed accrual with the results expected in the near future. Besides monotherapy with PROSTVAC, various rationale combinatorial regimens hold promise. These include combining PROSTVAC with immune check point inhibitors, second-generation androgen receptor blockers and other immune enhancing strategies such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Based on the results of previously reported randomized studies of iplimumab and sipuleucel-T in prostate cancer, there are important considerations which the ongoing investigations would need to take in to account. It is very likely that the subset of men who may derive the maximum benefit from PROSTVAC are those with low disease burden and/or indolent disease. In men with relatively high disease burden, it may be a prudent strategy to employ a cytoreductive agent for adequate tumor debulking prior to treatment with PROSTVAC. Lastly, investigation in to the identification of biomarkers predictive of response to PROSTVAC will help select men who are best suited for treatment with PROSTVAC. Given minimal toxicities and a novel mechanism of action, regulatory approval of PROSTVAC is expected to not only extend survival, but also improve quality of life of men with prostate cancer.

Executive Summary.

Mechanism of action

PROSTVAC is a recombinant vaccinia (prime) and fowlpox (boost) virus vector based immunotherapy regimen containing transgenes for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and three costimulatory antigens B7-1, ICAM and LFA-3.

PROSTVAC induces T-cell activation and proliferation through engagement of T-cell receptor leading to an antitumor response.

Pharmacokinetic & pharmacodynamics

Traditional measures of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics do not apply to PROSTVAC immunotherapy, as it utilizes live viruses.

Recently conducted Phase II and III clinical trials of PROSTVAC employed subcutaneous route of administration, although, PROSTVAC has been administered through intradermal and intramuscular routes during earlier phases of development.

T-cell-mediated response has been observed in 11–72% patients receiving PROSTVAC using ELISPOT test.

Plaque testing can detect live virus up to 14 days after drug administration.

PROSTVAC does induce antibodies to vaccinia virus in all patients but PSA-specific antibodies have been rarely observed.

Safety & tolerability

Systemic side effects are rarely seen. Adverse effects profile mainly comprises local injection site reaction including erythema, pain and swelling.

Grade 3 systemic side effects include fatigue, nausea and fever, and are observed in ∼1% of patients.

Grade 2 injection site reaction have been observed in ∼25% patients.

Contraindicated in patients with prior history of hypersensitivities to the vector.

No reports of contact transmission or inadvertent inoculation.

Clinical efficacy

PROSTVAC is undergoing investigation for use in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Phase II clinical trial showed significant improvement in overall survival (25.1 vs 16.6 months; hazard ratio: 0.56; p = 0.0061) in patients with minimally symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

PROSTVAC appears to be most promising in a clinical setting of low volume and slowly progressing disease.

Drug interactions

PROSTVAC has been observed to be safe in combination with chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, check point inhibitors and radiation therapy.

Immune surrogate markers indicate efficacy in presence of concurrent therapy and does not appear to negatively impact other treatments.

Dosing & administration

Priming dose – 2.00 × 108 plaque forming unit (0.5 ml) is injected subcutaneous with a 25 gauge needle into the skin of the upper and outer arm. It is recommended to cover the injection site with dry gauge and avoid individuals at high risk for vaccinia related complication for 7–10 days.

Booster dose – 1.0 × 108 plaque forming unit of rF-PSA administered every 2 weeks, subcutaneous with 25 gauge needle injection site is covered with dry gauge, for a total of 6 doses.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure: The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or p ending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Disclosure: In addition to the peer-review process, with the author(s) consent, the manufacturer of the product(s) discussed in this article was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for factual accuracy. Changes were made at the discretion of the author(s) and based on scientific or editorial merit only.

References

Papers of special interest have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford ED, Eisenberger MA, McLeod DG, et al. A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(7):419–424. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908173210702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal N, Padmanabh S, Vogelzang NJ. Development of novel immune interventions for prostate cancery. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10(2):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6••.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumenstein BA, et al. Overall survival analysis of a Phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1099–1105. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0597. Phase II randomized trial which is precursor for the large Phase III trial. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schellhammer PF, Chodak G, Whitmore JB, Sims R, Frohlich MW, Kantoff PW. Lower baseline prostate-specific antigen is associated with a greater overall survival benefit from sipuleucel-T in the Immunotherapy for Prostate Adenocarcinoma Treatment (IMPACT) trial. Urology. 2013;81(6):1297–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong L, Small EJ. Anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 antibody: the first in an emerging class of immunomodulatory antibodies for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5275–5283. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.8954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese Z, Straubhar A, Pal SK, Agarwal N. Ipilimumab in the treatment of prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2015;11(1):27–37. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184–043): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):700–712. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70189-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulley JL, Madan RA, Tsang KY, et al. Immune impact induced by PROSTVAC (PSA-TRICOM), a therapeutic vaccine for prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(2):133–141. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madan RA, Heery CR, Gulley JL. Poxviral-based vaccine elicits immunologic responses in prostate cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e28611. doi: 10.4161/onci.28611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake CG. Prostate cancer as a model for tumour immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2010;10(8):580–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandl SJ, Rountree RB, Dela Cruz TB, et al. Elucidating immunologic mechanisms of PROSTVAC cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2014;2(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s40425-014-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Hodge JW, Sabzevari H, Yafal AG, Gritz L, Lorenz MG, Schlom J. A triad of costimulatory molecules synergize to amplify T-cell activation. Cancer Res. 1999;59(22):5800–5807. Rationalizes the use of costimulatory molecules beside prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for effective immunotherapy regimen. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulley J, Chen AP, Dahut W, et al. Phase I study of a vaccine using recombinant vaccinia virus expressing PSA (rV-PSA) in patients with metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Prostate. 2002;53(2):109–117. doi: 10.1002/pros.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman HL, Wang W, Manola J, et al. Phase II randomized study of vaccine treatment of advanced prostate cancer (E7897): a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2122–2132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy B, Panicalli D, Marshall J. TRICOM: enhanced vaccines as anticancer therapy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(4):397–402. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiPaola RS, Plante M, Kaufman H, et al. A Phase I trial of pox PSA vaccines (PROSTVAC-VF) with B7–1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 co-stimulatory molecules (TRICOM) in patients with prostate cancer. J Transl Med. 2006;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arlen PM, Skarupa L, Pazdur M, et al. Clinical safety of a viral vector based prostate cancer vaccine strategy. J Urol. 2007;178(4 Pt 1):1515–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21••.Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Madan RA et al. Immunologic and prognostic factors associated with overall survival employing a poxviral-based PSA vaccine in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59(5):663–674. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0782-8. Assesses the prognostic factors for immune response to PROSTVAC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Madan RA, Mohebtash M, Arlen PM, et al. Ipilimumab and a poxviral vaccine targeting prostate-specific antigen in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a Phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):501–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70006-2. Assesses the safety of combination immunotherapy regimen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh H, Madan RA, Dahut WL, et al. Combining active immunotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(Suppl 7) Abstract 172. [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Bastian A, et al. Combining a recombinant cancer vaccine with standard definitive radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(9):3353–3362. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2062. Clinical trial assessing the combination of radiotherapy with PROSTVAC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heery CR, Madan RM, Bilusic M, et al. A Phase II randomized clinical trial of samarium-153 EDTMP (Sm-153) with or without PSA-tricom vaccine in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) after docetaxel. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl. 6) Abstract 102. [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Arlen PM, Gulley JL, Parker C, et al. A randomized Phase II study of concurrent docetaxel plus vaccine versus vaccine alone in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;12(4):1260–1269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2059. Clinical trial combining chemotherapy with PROSTVAC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madan RA, Gulley JL, Schlom J, et al. Analysis of overall survival in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with vaccine, nilutamide, and combination therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;14(14):4526–4531. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilusic M, Gulley JL, Heery C, et al. A randomized Phase II study of flutamide with or without PSA-TRICOM in nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl. 7) Abstract 163. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Camphausen K, et al. Irradiation of tumor cells up-regulates Fas and enhances CTL lytic activity and CTL adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md 1950) 2003;170(12):6338–6347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Coleman CN, Camphausen K, Schlom J, Hodge JW. External beam radiation of tumors alters phenotype of tumor cells to render them susceptible to vaccine-mediated T-cell killing. Cancer Res. 2004;64(12):4328–4337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13(9):1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheard MA, Vojtesek B, Janakova L, Kovarik J, Zaloudik J. Up-regulation of Fas (CD95) in human p53wild-type cancer cells treated with ionizing radiation. Int J Cancer. 1997;73(5):757–762. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971127)73:5<757::aid-ijc24>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramakrishnan R, Assudani D, Nagaraj S, et al. Chemotherapy enhances tumor cell susceptibility to CTL-mediated killing during cancer immunotherapy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(4):1111–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI40269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lesterhuis WJ, Punt, Cornelis JA, Hato SV, et al. Platinum-based drugs disrupt STAT6-mediated suppression of immune responses against cancer in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(8):3100–3108. doi: 10.1172/JCI43656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowak AK, Lake RA, Marzo AL, et al. Induction of tumor cell apoptosis in vivo increases tumor antigen cross-presentation, cross-priming rather than cross-tolerizing host tumor-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(10):4905–4913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowak AK, Robinson, Bruce WS, Lake RA. Gemcitabine exerts a selective effect on the humoral immune response: implications for combination chemo-immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62(8):2353–2358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garnett CT, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Combination of docetaxel and recombinant vaccine enhances T-cell responses and antitumor activity: effects of docetaxel on immune enhancement. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(11):3536–3544. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Windmill KF, Lee VW. Effects of castration on the lymphocytes of the thymus, spleen and lymph nodes. Tissue Cell. 1998;30(1):104–111. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(98)80011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldberg GL, Sutherland JS, Hammet MV, et al. Sex steroid ablation enhances lymphoid recovery following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;80(11):1604–1613. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000183962.64777.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mercader M, Bodner BK, Moser MT, et al. T cell infiltration of the prostate induced by androgen withdrawal in patients with prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(25):14565–14570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251140998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41••.Kim JW, Marte JL, Singh NK, et al. Safety profile of recombinant poxviral TRICOM vaccines. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl) Abstract e16036. Safety analysis of Poxviral TRICOM-based immunotherapy regimens. [Google Scholar]