Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the two most common neurodegenerative disorders, and exact a burden on our society greater than cardiovascular disease and cancer combined. While cognitive and motor symptoms are used to define AD and PD, respectively, patients with both disorders exhibit sleep disturbances including insomnia, hypersomnia and excessive daytime napping. The molecular basis of perturbed sleep in AD and PD may involve damage to hypothalamic and brainstem nuclei that control sleep – wake cycles. Perturbations in neurotransmitter and hormone signaling (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine and melatonin) and the neurotrophic factor BDNF likely contribute to the disease process. Abnormal accumulations of neurotoxic forms of amyloid β-peptide, tau and α-synuclein occur in brain regions involved in the regulation of sleep in AD and PD patients, and are sufficient to cause sleep disturbances in animal models of these neurodegenerative disorders. Disturbed regulation of sleep often occurs early in the course of AD and PD, and may contribute to the cognitive and motor symptoms. Treatments that target signaling pathways that control sleep have been shown to retard the disease process in animal models of AD and PD, suggesting a potential for such interventions in humans at risk for, or in the early stages of these disorders.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, sleep, circadian

Introduction

Age-related disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythms are well documented (Brown et al., 2011; Crowley, 2011). However, recent data has shown that neurodegenerative diseases are often associated with sleep disturbances beyond what is observed in normal aging. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), characterized by memory loss, is associated with sleep abnormalities including increased sleep time and sleep fragmentation (Vitiello et al., 1990; McCurry et al., 1999). Although the causes of sleep abnormalities in AD are unknown, they often appear after diagnosis and seem to be a by-product of the disease rather than a direct effect of AD pathology in the brain. Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is characterized by a host of degenerative motor symptoms including resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, postural instability and freezing. Pathologically, PD brains show loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra leading to reduced input in the striatum. In addition, PD patients typically exhibit extensive brainstem pathology and associated autonomic nervous system (ANS) disturbances that often occur before motor signs (Gaig and Tolosa, 2009). As in AD, sleep disorders are also well documented in PD; however, unlike AD these often appear years before the hallmark motor dysfunction (Claassen et al., 2010). Further, while sleep behaviors have systematically been ruled out for AD classification and diagnosis, it is possible that some sleep disturbances may be useful for predicting the onset of PD (Bliwise et al., 1989; Vitiello et al., 1990; Schenck et al., 2003; Postuma et al., 2009). It is the goal of this review to outline clinical and experimental studies of sleep disturbances in AD and PD, and to briefly outline potential signaling molecules and brain regions thought to mediate these symptoms.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Sleep Disturbances in Alzheimer’s Patients

AD patients have been shown to experience alterations in normal sleep patterns that cannot be explained by aging alone. Clinical data demonstrate sleep disturbances such as nighttime sleep fragmentation, decreased slow wave sleep (SWS) and frequent daytime napping in as many as 25–35% of AD patients (McCurry et al., 1999; Moran et al., 2005). In one study of AD patients, 35% were reported to have at least one sleep-related disturbance in the previous week, with increased sleep time and early morning waking being the most common (McCurry et al., 1999). Sleep fragmentation, which can include frequent awakenings and an increase in daytime napping, is the most common sleep disturbance reported in AD patients with an incidence of roughly 30–50% (Vitiello et al., 1990). In addition to these disturbances, the latency to the first episode of REM sleep (REML) is shorter in AD patients (Bliwise et al., 1989). At least one study showed a genetic predisposition to sleep disturbances in AD patients who carried a mutation in the monoamine oxidase A gene, a gene shown to play a role in maintaining circadian rhythm (Craig et al., 2006). In fact, several studies show breakdowns in circadian rhythmicity in AD including an increase in ‘sundowning’, changes in activity patterns, and fluctuations in normal circadian changes in body temperature (van Someren et al., 1996; Volicer et al., 2001). However, despite the large number of clinical studies that outline sleep disturbance in AD patients, it is clear that these sleep symptoms are not diagnostically useful for determining early stage AD or for use as a biomarker for the disease (Bliwise et al., 1989; Vitiello et al., 1990).

Sleep Disturbances in Animal Models of AD

Very few studies to date have described sleep disturbances in animal models of AD. Two separate studies documented disturbances in the rapid-eye-movement (REM) phase of sleep in an in vivo genetic mouse model of AD including a reduction in total REMS and REM bouts (Wisor et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005). EEG recordings in Tg2576 mice, which overexpress the FAD Swedish hAPP695 mutation gene, revealed reduced REM sleep at 6 and 12, but not 2, months of age (Zhang et al., 2005) implying an age-related reduction in REM sleep in this model. The circadian period was also lengthened in Tg2576 mice compared to controls (Wisor et al., 2005). Further, one study identified a class of cholinergic neurons that are compromised in this model of AD which could indicate that a breakdown of cholinergic signaling is responsible for the age-related reduction in REMS (Zhang et al., 2005). This hypothesis was further strengthened by work that showed that the wake-promoting actions of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil were dampened in AD mice implying a role for cholinergic transmission in sleep abnormalities in AD. Finally, wheel-running analysis of circadian patterns in the 3xTgAD model of AD showed an increase in activity during what is normally an inactive phase and a decrease in activity during what is normally an active phase compared to controls, implying a breakdown in circadian patterns in this model of AD (Sterniczuk et al., 2010).

Potential Mechanisms of Sleep Disturbance in AD

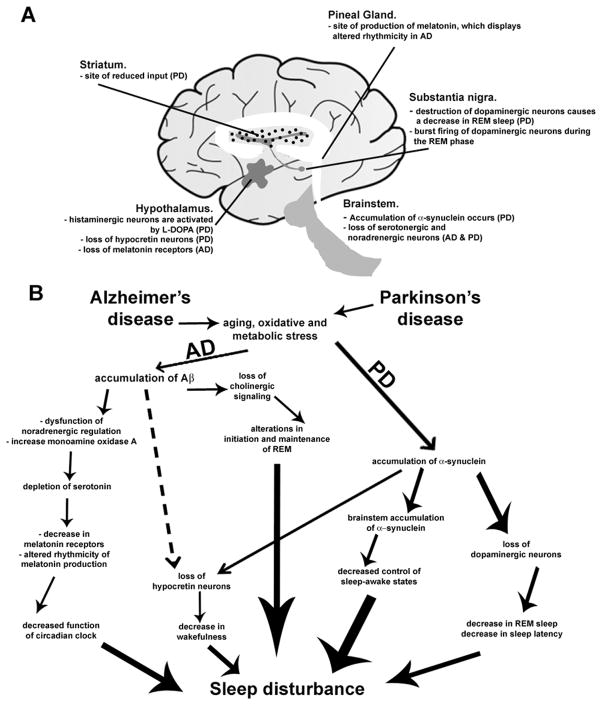

Alterations in hypocretin signaling

The hypocretins (orexins) are a class of excitatory neurotransmitter hormones that are thought promote wakefulness; narcolepsy is associated with a decrease in hypocretin signaling (Kroeger & Lecea, 2009; Tsunematsu et al., 2011). A recent clinical study showed a 40% reduction in hypocretin-1 positive neurons in post-mortem hypothalami of AD patients compared to controls (Figure 1A) (Fronczek et al., 2011). Further, cerebrospinal fluid levels of hypocretin were also reduced in AD patients compared to controls, further indicating a role for this neurotransmitter in mediating sleep disturbances in AD. In fact, one study measured an inverse correlation between CSF hypocretin levels and wake fragmentation in AD patients (Friedman et al., 2007). Finally, orexinergic signaling has been shown to be responsible for diurnal changes in interstitial Aβ levels, further implying that hypocretin/orexin signaling has an important role in the pathogenesis of AD (Kang et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms underlying sleep disorders in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. (A) Brain regions involved in regulating sleep are susceptible to disease pathology in both AD and PD. (B) Sequences of events that may lead to sleep disturbances in neurodegenerative diseases. It is noteworthy that although accumulation of Aβ or α-synuclein may occur prior to the onset of sleep disturbances, it is often the case, particularly in PD, that sleep symptoms appear well before the hallmark deficits of the disease (motor dysfunction, in the case of PD).

Disruptions in cholinergic signaling

Cholinergic signaling plays an important role in sleep regulation and many studies outline alterations in cholinergic neurotransmission in AD (German et al., 2003; Berkowitz et al., 1990). Postmortem studies show a loss of cholinergic neurons in the forebrain in dementia, and MRI confirms a decrease in the volume of the basal forebrain cholinergic system in AD (McGeer et al., 1984; Grothe et al., 2011). Transgenic mice overexpressing mutant human amyloid precursor protein (PDAPP) develop AD-like accumulation of amyloid-β, and even prior to the appearance of AD pathology these mice display a loss of cholinergic nerve terminals in the cortex (German et al., 2003). AD patients display lower levels of the ACh-synthesizing enzyme choline acetyltransferase in the brain further implying a loss of cholinergic signaling in AD (Giacobini, 2003). It is possible that cholinergic neurons are more susceptible to the neurotoxic effects of Aβ deposition, as shown using Aβ injections in the rat (Harkany et al., 2000, 2001). Initiation and maintenance of the REM phase of sleep depends on cholinergic signaling; as shown in both experimental and clinical studies (Berkowitz et al., 1990; Wisor et al., 2005). The crucial role of cholinergic neurons in mediating REM sleep and their susceptibility to damage in AD lends credence to the hypothesis that this class of neurons mediates sleep alterations in AD. Donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, is commonly prescribed for AD-type dementia and administration of donepezil increases REM sleep in AD patients, further implying that cholinergic signaling mediates sleep alterations in AD (Moraes-Wdos et al., 2006).

Cholinergic deficits have also been reported to result in impaired attention relatively early in the disease course in the 3xTgAD mouse model of AD (Romberg et al., 2011). When presented with short duration stimuli with unpredictable locations on a touchscreen the 3xTgAD were less accurate in responding to the stimulus and were more likely to make perseverative responses that wild-type mice. Performance in the tests of attention was restored to normal in 3xTgAD mice in response to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil (Aricept), suggesting that a cholinergic deficit was responsible for the impaired attention in the 3xTgAD mice. The alterations in attention in the 3xTgAD mice appear similar to attentional abnormalities in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD who often have difficulty in focusing on tasks and are easily distracted (Baddeley et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2007; Saunders and Summers, 2010). A link between disturbed sleep pattern and attentional deficits remains to be established, although it is known that attention is impaired in shift workers (Niu et al., 2011).

Melatonin

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is produced in high amounts by cells in the pineal gland in a sleep-related pulsatile manner such that its levels increase shortly before bedtime and decrease in response to the light of daybreak (for review see Hardeland et al., 2011). Ingestion of melatonin can promote sleep and can promote a resetting of the circadian clock. Melatonin is also produced in lower amounts by cells in other brain regions as well as by some cells in peripheral tissues. Receptors for melatonin, which are coupled to G-protein (Gi)-linked receptors that reduce levels of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Melatonin receptors are expressed in many different cell types including those of the nervous, cardiovascular, digestive and endocrine systems. AD patients exhibit reduced levels of melatonin receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus (Wu et al., 2007) and have an altered rhythmicity of melatonin production (Mishima et al., 1999; Skene and Swaab, 2003). These findings suggest a role for perturbed melatonin signaling in the sleep disturbances that are common in AD patients.

It has also been suggested that reduced melatonin signaling contributes to the pathogenesis of AD by promoting the dysfunction and degeneration of neurons in circuits involved in cognition. Several intervention studies in animal models of AD have demonstrated ameliorative effects on disease processes. Matsubara et al. (2003) found that administration of melatonin to APP mutant mice resulted in a reduction in brain levels of Aβ and protein nitration (a marker of oxidative stress) and increased the survival of the mice. Similarly, levels of lipid peroxidation were decreased and levels of glutathione (an endogenous antioxidant) were increased in the brains of APP mutant mice, and this lessening of oxidative stress was associated with reduced expression of proteins involved in apoptosis (programmed cell death) including Bax, Par-4 and caspase-3 (Feng et al., 2006). Olcese et al. (2009) administered melatonin in the drinking water to APP/PS1 double-mutant mice for 5 months and then assessed the behavior of the mice using tests of spatial reference memory and working memory. Whereas the control APP/PS1 mutant mice exhibited severe cognitive impairment, the melatonin-treated AD mice did not. Interestingly, APP mutant mice exhibit heightened anxiety at the end of the dark period (preceding their normal sleep period) which is similar to ‘sundowning’ (increased agitation in the evening) in AD patients (Bedrosian et al., 2011).

Serotonin and Norepinephrine Signaling

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and norepinephrine are produced primarily in neurons of the brainstem raphe nucleus and locus coeruleus, respectively; the axons of these serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons innervate neurons throughout the cerebral cortex and limbic system (Moore, 1993). Data from pharmacological studies, human and mouse genetics, and clinical investigations have revealed prominent roles for serotonin in the regulation of mood, cognition and sleep (Robbins, 1997; Gingrich, 2002; Myhrer, 2003; McMorris et al., 2006). There is now a large literature describing serotonergic and noradrenergic deficits in AD which manifest as degeneration of neurons in the raphe nucleus and locus coeruleus, and reduced cortical levels of these neurotransmitters (Figure 1A) (Palmer and DeKosky, 1993; Michelsen et al., 2008). A history of depression, a disorder involving both sleep disturbances and reduced serotonin and norepinephrine signaling, is a risk factor for AD (Michelson et al., 2008). It is therefore reasonable to consider the possibility that deficits in one or both of these monoamine neurotransmitter signaling systems occur early in AD, perhaps even prior to cognitive impairment.

Serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine, sertraline and fluoxetine can improve affective behaviors in patients with AD which may result in improved cognitive function (Chow et al., 2007). Clinical trials of SSRIs in elderly subjects with depression have revealed beneficial effects on cognitive function (Muijsers et al., 2002). Recent studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of long-term treatment, beginning at a presymptomatic stage, on the disease process and cognition in mouse models of AD. For example, Nelson et al. (2007) found that treatment of 3xTgAD mice with paroxetine for 5 months resulted in improved spatial learning ability and reduced anxiety-like behavior, which were associated with reduced levels of Aβ and tau pathologies in the hippocampus. Beneficial effects of the SSRIs fluoxetine (Dong et al., 2004) and citalopram (Cirrito et al., 2011) in mouse models of AD have also been reported. In a small study of cognitively normal human subjects it was found that those that had been treated with SSRIs had significantly less Aβ (measured by PET imaging using an amyloid probe called PIB) compared to those who had not been treated with the antidepressants (Cirrito et al., 2011). The molecular mechanisms by which SSRIs counteract the disease process and improve cognition may include stimulation of BDNF production (Mattson et al., 2004), neurogenesis (Boldrini et al., 2009) and suppression of APP expression (Tucker et al., 2006). Norepinephrine plays an important role in learning and memory by enhancing synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Harley, 1991). AD patients exhibit profound loss of noradrenergic innervation of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Powers et al., 1988; Weinshenker, 2008). Similarly, aged dogs with cognitive impairment have significantly fewer noradrenergic neurons in their locus coeruleus compared to age-matched cognitively normal dogs (Insua et al., 2010). Selective depletion of norepinephrine in APP mutant mice results in an acceleration of Aβ deposition and inflammation in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Heneka et al., 2002; Kalinin et al., 2007). It is not known if deficits in norepinephrine signaling contribute to sleep disturbances and cognitive impairment in AD. However, given the evidence that norepinephrine stimulates BDNF production and neurogenesis, and can enhance cognitive function, trials of agents that enhance noradrenergic signaling in AD patients are warranted.

Parkinson’s Disease

Clinical Studies of Sleep Disturbance in PD

A plethora of clinical studies confirm that a host of sleep disturbances are associated with PD and these may appear decades before the appearance of the traditional motor symptoms of PD (Eisensehr et al., 2003; Comella 2003; Maria et al., 2003; Dauvilliers 2007; Claassen et al., 2010). Sleep disturbance is among the most common non-motor symptoms of PD with an incidence in the range of 60–98% of PD patients. It is often the cause of major discomfort in patients (Lees et al., 1988; Tandberg et al., 1998; Comella 2007).

The most common sleep complaint in PD patients is frequent nocturnal awakenings and sleep fragmentation (Factor et al., 1990; Tandberg 1998; Comella 2003). PD patients complain of frequent awakenings which, if prolonged, can result in an overall reduction in sleep time eventually causing excessive daytime sleepiness.

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), characterized by dream enactment accompanied by excessive motor activity, is associated with PD with roughly a third of PD patients displaying this sleep disorder (Gagnon et al., 2002). RBD is observed in other α-synucleinopathies beyond just PD, including multiple system atrophy and dementia with Lewy bodies (Comella 2003; Boeve et al., 2007; Postuma et al., 2009). Recent studies have shown that RBD can appear prior to the motor symptoms associated with PD and other α-synucleinopathies. In fact, at least one study showed that at a mean follow up of 10 years 65% of patients who present with RBD go on to develop a neurodegenerative disease (Schenck et al., 2003). Although a second study found a lower percentage at a 12 year follow up (52.4%), that study found that a majority of RBD patients developing neurodegenerative diseases presented with α-synucleinopathies (Postuma et al., 2009).

Sleep Disturbances in Animal Models of PD

Sleep disturbances in early and confirmed PD are well documented and widely accepted. However, despite the range of clinical data on sleep disorders and the great number of animal models of PD, few studies to date describe clinically relevant sleep abnormalities.

One of the most common animals of PD employs neurotoxin injections to eliminate dopaminergic transmission, with the most widely used toxin for this purpose being 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropuridine (MPTP). Injection of MPTP induces motor dysfunction and a loss of dopaminergic neurons in mice and monkeys, thus mimicking pathology and behavior of PD (Burns et al., 1983). In addition, a range of animal models show alterations in sleep patterns following MPTP injection. EEG indicates that rhesus monkeys demonstrate deregulation of REM sleep following MPTP injection and this sleep abnormality precedes the appearance of motor dysfunction (Barraud et al., 2009). Similarly, MPTP injection disrupts normal muscle atonia during paradoxical sleep in the marmoset, reminiscent of RBD (Verhave et al., 2011). Paradoxical sleep is also reduced in the mouse, rat and cat following MPTP injection (Pungor et al., 1990; Lima et al., 2007; Laloux et al., 2008a; McDowell et al., 2010). This effect appears to extend to other, less common neurotoxins; ingestion of the environmental toxin cycad causes hypersomnolescence as evidenced on EEG in rats (McDowell et al., 2010).

MPTP-induced PD demonstrates both the primary motor symptoms of the disease as well as the non-motor symptoms of perturbed sleep, as described above. However, these models lack full clinical relevance due to the severity of the insult as well as the lack of progression of dysfunction. For this reason, many researchers use α-synuclein overexpressing animal models of PD which exhibit slower progression of dopaminergic neuron dysfunction and associated motor symptoms (Kudo et al., 2011). While α-synuclein accumulation is considered a hallmark of PD, much less is known regarding the effect of α-synuclein accumulation on sleep. Recently, Kudo et al. used wheel running patterns to evaluate circadian patterns in a transgenic mouse overexpressing α-synuclein. They observed lower nighttime activity and fragmented wheel running activity in the α-synuclein overexpressing mice compared to wild-type controls (Kudo et al., 2011). Consistent with these alterations in sleep behaviors, the authors observed reduced neuronal firing in the superchiasmatic nucleus. Although this paper is the first of its kind to outline sleep patterns in a α-synuclein based mouse model of PD, at least one other genetic model of PD demonstrates sleep alterations. Mice with a reduction in expression of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT-2) display increased oxidative stress, loss of dopaminergic terminals, cell loss in the substantia nigra and accumulation of α-synuclein making this model relevant to PD (Taylor et al., 2009). In addition to the hallmark PD pathologies, VMAT-2 deficient mice display dampened circadian rhythms and reduced latency to sleep, further lending clinical relevance to this mouse model of PD (Taylor et al., 2009).

Potential Mechanisms of Sleep Disturbance in PD

Dopaminergic Signaling

The exact mechanisms by which sleep behaviors are disrupted in PD are not entirely known, however, unlike AD, it appears that sleep alterations are directly related to the disease pathology. As outlined above, administration of toxins that target dopaminergic neurons result in sleep abnormalities in a range of animal models (Barraud et al., 2009; Verhave et al., 2011; Lima et al., 2007; Pungor et al., 1990; McDowell et al., 2010; Laloux et al., 2008a). In fact, administration of MPTP directly to the substantia nigra results in a decrease in REM sleep and a decrease in sleep latency (Lima et al., 2007). Further, both PD and schizophrenia are associated with sleep disorders although PD is related to a lack of dopamine and schizophrenia is related to an increase (Sarkar et al., 2010). It is possible that destruction of dopaminergic signaling in PD causes a breakdown in the control of wakefulness leading to increased excessive daytime sleepiness. In other words, a decrease in dopamine in PD could potentially be responsible for excessive daytime napping due to the arousal-related role of dopamine. Dopamine has been shown to promote wakefulness in variety of animal models including drosophila and mice (Andretic 2005; Qu et al., 2010). L-DOPA, the dopamine precursor that passes through the blood-brain barrier, activates histaminergic neurons in the hypothalamus which promote wakefulness (Figures 1A & 1B) (Yanovsky 2011). Dopamine receptor agonists promote wakefulness (Isaac & Berridge 2003). Conversely, dopaminergic signaling has also been demonstrated to be associated with sleepiness and the sleep state. An increase in dopamine release is observed during the REM phase of sleep in the cortex, nucleus accumbens and midbrain (Lena et al., 2005; Maloney 2002). Additionally, using EEG readings in the midbrain, Dahan et al., observed a pattern of burst firing of dopaminergic neurons during the REM phase; a phenomenon associated with a synaptic release of dopamine (Dahan et al., 2007; Monti & Monti 2007). Further evidence for a role of dopamine in mediating sleep lies in the increase in dopamine measured in the forebrain after sleep deprivation, which could perhaps indicate a compensatory mechanism designed to promote rebound sleep (Zant et al., 2011).

There are several possible explanations for this apparent discrepancy. It is possible that different dopamine receptors mediate wakefulness and sleep. In an EEG study of D2R knockout mice, periods of wakefulness were reduced compared to wild-type controls (Qu et al., 2010). It is also possible that dopamine acts to mediate both wakefulness and sleep depending on the concentration of the neurotransmitter. Dopamine demonstrates this ‘U’ shape effect for several physiological phenomena (Monte-Silva et al., 2009; Seamans and Yang, 2004). For example, either insufficient or excessive dopamine impairs cognitive functions (Cai and Arnsten, 1997; Seamans and Yang, 2004). Finally, it should be noted that both of these explanations may suffice; differing concentrations of dopamine may activate different classes of receptors based on receptor affinity.

Brainstem accumulation of α-synuclein

A second hypothesis for the etiology of sleep disorders in PD is that it is caused by accumulation of α-synuclein in the brainstem. As mentioned above, RBD is common in PD and can precede the appearance of α-synucleinopathies by many years. Although the pathology of RBD is unknown, some theories include degeneration of lower brainstem nuclei; there is evidence of postganglionic sympathetic denervation and cardiac autonomic dysfunction in RBD (Miyamoto et al., 2006; Mitra & Chaudhuri, 2009; Postuma et al., 2010). Further, ample evidence exists for the presence of PD pathology, including α-synuclein accumulations and Lewy bodies, in the brainstem of PD patients. The areas of the brainstem involved in the regulation of sleep, wakefulness and arousal are the pendunculopontine nucleus, the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, the locus coeruleus, and the dorsal raphe and all of these regions show lesions at an early stage of the disease prior to the onset of motor symptoms (Hirsch et al., 1987; Hobson & Pace-Schott, 2002; Pace-Schott & Hobson, 2002; Turner, 2002; Braak et al., 2003; Grinberg et al., 2010). Thus, brainstem pathology appears early in the disease state similar to the early appearance of sleep alterations relative to motor symptoms, which implies a role for the brainstem in mediating sleep disturbances in PD.

Hypocretin Signaling

In PD patients, the hypothalamus, which regulates sleep and metabolism, shows evidence of the presence of Lewy bodies, potentially indicating that PD pathology in the brain directly influences sleep patterns (Fronczek et al., 2007; Kremer & Bots, 1993). The hypocretins (orexins) are a class of excitatory neurotransmitter hormones that are thought promote wakefulness (Tsunematsu et al., 2011). Narcolepsy is associated with a decrease in hypocretin signaling (Kroeger & Lecea, 2009). There is evidence of a loss of hypocretin positive cells in the hypothalamus in PD patients implying a role for hypocretin signaling in sleep disturbances in PD. Hypocretin-positive cells are also decreased in the cortex as well, and CSF hypocretin levels are also decreased in PD patients compared to controls (Fronczek et al., 2007; Lessig et al., 2010). Further, at least one study showed an increase in the loss of hypocretin cells with PD progression; hypocretin cell loss in stage 1 was only 23% but reached 65% by stage 5 (Thannickal et al., 2007).

Future Directions

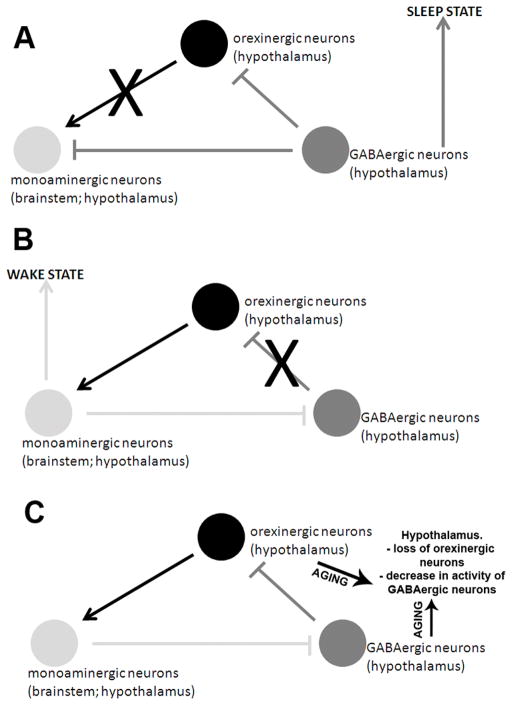

The functional and structural integrity of neuronal circuits that play critical roles in the regulation of sleep is compromised in AD and PD. One clue to understanding why this is so comes from evidence that several of the major risk factors for sleep disorders are also risk factors for AD and PD including old age (Thal et al., 2004; Crowley, 2011), depression (Franzen and Buysse, 2008), obesity/diabetes (Tasali et al., 2009; Riederer et al., 2011) and a sedentary lifestyle (Santos et al., 2007; Lang-Asschenfeldt and Kojda, 2008). Elucidating the mechanism(s) that explains these shared risk factors should identify convergence points in the pathogenesis of age-related sleep disorders and AD and PD. One possibility is that neurons that regulate sleep are vulnerable because they are rendered unable to cope with the cellular stresses that occur in aging and neurodegenerative disorders (Figure 1B). Indeed, old age, excessive energy intake and lack of exercise all impair the ability of neurons to respond adaptively to stress resulting in increased oxidative stress and accumulation of damaged/misfolded/aggregated proteins (Figure 2) (Chen and Russo-Neustadt, 2007; Stranahan et al., 2009; Arumugam et al., 2010; Martin et al., 2010). Consistent with this notion, noradrenergic and orexinergic neurons in sleep circuits of aged animals exhibit reduced responsiveness to wakefulness and an aberrant endoplasmic reticulum stress response (Naidoo et al., 2011). A better understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms shared in age-related sleep disorders and AD and PD may lead to novel interventions for the prevention and treatment of all of these disorders.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms by which aging may disrupt the function of neural circuits that regulate sleep – wake cycles. (A) During the sleep state, γ-aminobutyric acid, or GABA, inhibits neurons in both the brainstem and the hypothalamus. During the ‘wake’ state (B), GABAergic neurons in the hypothalamus are inhibited by monoaminergic neurons in the brainstem and hypothalamus. In aging, (C), the hypothalamus experiences both a loss of hypocretin/orexinergic neurons and also a decrease in GABAergic signaling thus disrupting the sleep-wake cycle.

Two environmental factors that may reduce the risks of sleep disorders, AD and PD are regular exercise and moderation in dietary energy intake (Sherrill et al., 1998; Luchsinger et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2010; Ahlskog, 2011). Both exercise and dietary energy restriction have been shown to counteract the disease process at the molecular and cellular levels in animal models of AD (Adlard et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Halagappa et al., 2007; Parachikova et al., 2008) and PD (Duan and Mattson, 1999; Maswood et al., 2004; Zigmond et al., 2009; Lau et al., 2011). Both exercise and energy restriction enhance neurotrophic factor signaling and up-regulate mechanisms that protect against the aberrant accumulation of self-aggregating proteins including Aβ and α-synuclein (Walker et al., 2006; Irvine et al., 2008). Elucidation of the mechanisms by which exercise and energy restriction counteract the age-related sleep disorders and neurodegenerative disorders should be a major goal of future research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported entirely by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging

References

- Adlard PA, Perreau VM, Pop V, Cotman CW. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4217–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlskog JE. Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology. 2011;77:288–294. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andretic R, van Swinderen B, Greenspan RJ. Dopaminergic modulation of arousal in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Phillips TM, Cheng A, Morrell CH, Mattson MP, Wan R. Age and energy intake interact to modify cell stress pathways and stroke outcome. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:41–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.21798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnulf I, Leu S, Oudiette D. Abnormal sleep and sleepiness in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:472–477. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328305044d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Baddeley HA, Bucks RS, Wilcock GK. Attentional control in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2001;124:1492–1508. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.8.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, Cholerton BA, Plymate SR, Fishel MA, Watson GS, Duncan GE, Mehta PD, Craft S. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:569–579. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedrosian TA, Herring KL, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Altered temporal patterns of anxiety in aged and amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11686–11691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103098108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz A, Sutton L, Janowsky DS, Gillin JC. Pilocarpine, an orally active muscarinic cholinergic agonist, induces REM sleep and reduces delta sleep in normal volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 1990;33:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90064-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliwise DL, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA, Davies H, Pursley AM, Petta DE, Widrow L, Guilleminault C, Zarcone VP, Dement WC. REM latency in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiat. 1989a;25:320–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeve BF, Silber MH, Saper CB, Ferman TJ, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Benarroch EE, Ahlskog JE, Smith GE, Caselli RC, Tippman-Peikert M, Olson EJ, Lin SC, Young T, Wszolek Z, Schenck CH, Mahowald MW, Castillo PR, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2007;130:2770–2788. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini M, Underwood MD, Hen R, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, John Mann J, Arango V. Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2376–2389. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Schmitt K, Eckert A. Aging and circadian disruption: causes and effects. Aging. 2011;3:813–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RS, Chiueh CC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Jacobowitz DM, Kopin IJ. A primate model of parkinsonism—selective destruction of dopaminergic-neurons in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra by n-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. PNAS. 1983;80:4546–4550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai JX, Arnsten AFT. Dose-dependent effects of the dopamine D1 receptor agonists A77636 or SKF81297 on spatial working memory in aged monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Russo-Neustadt AA. Running exercise- and antidepressant-induced increases in growth and survival-associated signaling molecules are IGF-dependent. Growth Factors. 2007;25:118–131. doi: 10.1080/08977190701602329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow TW, Pollock BG, Milgram NW. Potential cognitive enhancing and disease modification effects of SSRIs for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:627–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Disabato BM, Restivo JL, Verges DK, Goebel WD, Sathyan A, Hayreh D, D’Angelo G, Benzinger T, Yoon H, Kim J, Morris JC, Mintun MA, Sheline YI. Serotonin signaling is associated with lower amyloid-{beta} levels and plaques in transgenic mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14968–14973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107411108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Silber MH, Tippmann-Peikert M, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology. 2010;75:494–499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7fac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig D, Hart DJ, Passmore AP. Genetically increased risk of sleep disruption in Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. 2006;29:1003–1007. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.8.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley K. Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:41–53. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan L, Astier B, Vautrelle N, Urbain N, Kocsis B, Chouvet G. Prominent burst firing of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area during paradoxical sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1232–1241. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Goico B, Martin M, Csernansky CA, Bertchume A, Csernansky JG. Modulation of hippocampal cell proliferation, memory, and amyloid plaque deposition in APPsw (Tg2576) mutant mice by isolation stress. Neuroscience. 2004;127:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W, Mattson MP. Dietary restriction and 2-deoxyglucose administration improve behavioral outcome and reduce degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:195–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990715)57:2<195::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisensehr I, Linke R, Noachtar S, Schwarz J, Gildehaus FJ, Tatsch K. Reduced striatal dopamine transporters in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Comparison with Parkinson’s disease and controls. Brain. 2000;123:1155–1160. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factor SA, McAlarney T, Sanchez-Ramos JR, Weiner WJ. Sleep disorders and sleep effect in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1990;5:280–285. doi: 10.1002/mds.870050404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Qin C, Chang Y, Zhang JT. Early melatonin supplementation alleviates oxidative stress in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LF, Zeitzer JM, Lin L, Hoff D, Mignot E, Peskind ER, Yesavage JA. In Alzheimer disease, increased wake fragmentation found in those with lower hypocretin-1. Neurology. 2007;68:793–794. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256731.57544.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18:425–432. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:473–481. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronczek R, Overeem S, Lee SY, Hegeman IM, van Pelt J, van Duinen SG, Lammers GJ, Swaab DF. Hypocretin (orexin) loss in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:1577–1585. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronczek R, van Geest S, Frölich M, Overeem S, Roelandse FW, Lammers GJ, Swaab DF. Hypocretin (orexin) loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.03.014. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaig C, Tolosa E. When does Parkinson’s disease begin? Mov Disord. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S656–664. doi: 10.1002/mds.22672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon JF, Bédard MA, Fantini ML, Petit D, Panisset M, Rompré S, Carrier J, Montplaisir J. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2002;59:585–589. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Yazdani U, Speciale SG, Pasbakhsh P, Games D, Liang CL. Cholinergic neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:371–381. doi: 10.1002/cne.10737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini E. Cholinergic function and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:S1–5. doi: 10.1002/gps.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich JA. Mutational analysis of the serotonergic system: recent findings using knockout mice. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:449–465. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg LT, Rueb U, Alho AT, Heinsen H. Brainstem pathology and non-motor symptoms in PD. J Neurol Sci. 2010;289:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe M, Heinsen H, Teipel SJ. Atrophy of the Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Over the Adult Age Range and in Early Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol Psychiat. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.019. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq IZ, Naidu Y, Reddy P, Chaudhuri KR. Narcolepsy in Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:879–884. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halagappa VK, Guo Z, Pearson M, Matsuoka Y, Cutler RG, Laferla FM, Mattson MP. Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction ameliorate age-related behavioral deficits in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Brown GM, Pandi-Perumal SR. Melatonin--a pleiotropic, orchestrating regulator molecule. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:350–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T, O’Mahony S, Keijser J, Kelly JP, Kónya C, Borostyánkoi ZA, Görcs TJ, Zarándi M, Penke B, Leonard BE, Luiten PG. Beta-amyloid(1-42)-induced cholinergic lesions in rat nucleus basalis bidirectionally modulate serotonergic innervation of the basal forebrain and cerebral cortex. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:667–678. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T, Penke B, Luiten PG. beta-Amyloid excitotoxicity in rat magnocellular nucleus basalis. Effect of cortical deafferentation on cerebral blood flow regulation and implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;903:374–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley C. Noradrenergic and locus coeruleus modulation of the perforant path-evoked potential in rat dentate gyrus supports a role for the locus coeruleus in attentional and memorial processes. Prog Brain Res. 1991;88:307–321. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Galea E, Gavriluyk V, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Daeschner J, O’Banion MK, Weinberg G, Klockgether T, Feinstein DL. Noradrenergic depletion potentiates beta -amyloid-induced cortical inflammation: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2434–2442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02434.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, Graybiel AM, Duyckaerts C, Javoy-Agid F. Neuronal loss in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus in Parkinson disease and in progressive supranuclear palsy. PNAS. 1987;84:5976–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson JA, Pace-Schott EF. The cognitive neuroscience of sleep: neuronal systems, consciousness and learning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:679–693. doi: 10.1038/nrn915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insua D, Suárez ML, Santamarina G, Sarasa M, Pesini P. Dogs with canine counterpart of Alzheimer’s disease lose noradrenergic neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine GB, El-Agnaf OM, Shankar GM, Walsh DM. Protein aggregation in the brain: the molecular basis for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Mol Med. 2008;14:451–464. doi: 10.2119/2007-00100.Irvine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac SO, Berridge CW. Wake-promoting actions of dopamine D1 and D2 receptor stimulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:386–394. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinin S, Gavrilyuk V, Polak PE, Vasser R, Zhao J, Heneka MT, Feinstein DL. Noradrenaline deficiency in brain increases beta-amyloid plaque burden in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28l:1206–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, Fujiki N, Nishino S, Holtzman DM. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Lee BH, Seo SW, Moon SY, Jung DS, Park KH, Heilman KM, Na DL. Attentional distractibility by optokinetic stimulation in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69:1105–1112. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000276956.65528.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer HP, Bots GT. Lewy bodies in the lateral hypothalamus: do they imply neuronal loss? Mov Disord. 1993;8:315–320. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger D, de Lecea L. The hypocretins and their role in narcolepsy. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8:271–280. doi: 10.2174/187152709788921645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T, Loh DH, Truong D, Wu Y, Colwell CS. Circadian dysfunction in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.003. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloux C, Derambure P, Houdayer E, Jacquesson JM, Bordet R, Destée A, Monaca CJ. Effect of dopaminergic substances on sleep/wakefulness in saline- and MPTP-treated mice. Sleep Res. 2008a;17:101–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloux C, Derambure P, Kreisler A, Houdayer E, Bruezière S, Bordet R, Destée A, Monaca C. MPTP-treated mice: long-lasting loss of nigral TH-ir neurons but not paradoxical sleep alterations. Exp Brain Res. 2008b;186:635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Kojda G. Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular dysfunction and the benefits of exercise: from vessels to neurons. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau YS, Patki G, Das-Panja K, Le WD, Ahmad SO. Neuroprotective effects and mechanisms of exercise in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease with moderate neurodegeneration. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1264–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Blackburn NA, Campbell VL. The nighttime problems of Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1988;11:512–519. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léna I, Parrot S, Deschaux O, Muffat-Joly S, Sauvinet V, Renaud B, Suaud-Chagny MF, Gottesmann C. Variations in extracellular levels of dopamine, noradrenaline, glutamate, and aspartate across the sleep--wake cycle in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:891–899. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessig S, Ubhi K, Galasko D, Adame A, Pham E, Remidios K, Chang M, Hansen LA, Masliah E. Reduced hypocretin (orexin) levels in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroreport. 2010;21:756–760. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833bfb7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang FQ, Allen G, Earnest D. Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the circadian regulation of the suprachiasmatic pacemaker by light. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2978–2987. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02978.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima MM, Andersen ML, Reksidler AB, Vital MA, Tufik S. The role of the substantia nigra pars compacta in regulating sleep patterns in rats. PLoS One. 2007;2:e513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Caloric intake and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1258–1263. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.8.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney KJ, Mainville L, Jones BE. c-Fos expression in dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons of the ventral mesencephalic tegmentum after paradoxical sleep deprivation and recovery. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:774–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B, Ji S, Maudsley S, Mattson MP. “Control” laboratory rodents are metabolically morbid: why it matters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6127–6133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912955107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maswood N, Young J, Tilmont E, Zhang Z, Gash DM, Gerhardt GA, Grondin R, Roth GS, Mattison J, Lane MA, Carson RE, Cohen RM, Mouton PR, Quigley C, Mattson MP, Ingram DK. Caloric restriction increases neurotrophic factor levels and attenuates neurochemical and behavioral deficits in a primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18171–18176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405831102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara E, Bryant-Thomas T, Pacheco Quinto J, Henry TL, Poeggeler B, Herbert D, Cruz-Sanchez F, Chyan YJ, Smith MA, Perry G, Shoji M, Abe K, Leone A, Grundke-Ikbal I, Wilson GL, Ghiso J, Williams C, Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, Chain DG, Neria E. Melatonin increases survival and inhibits oxidative and amyloid pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1101–1108. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Maudsley S, Martin B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, Gibbons LE, Kukull WA, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Larson EB. Characteristics of sleep disturbance in community-dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12:53–59. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell KA, Hadjimarkou MM, Viechweg S, Rose AE, Clark SM, Yarowsky PJ, Mong JA. Sleep alterations in an environmental neurotoxin-induced model of parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 2010;226:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG, Suzuki J, Dolman CE, Nagai T. Aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and the cholinergic system of the basal forebrain. Neurology. 1984;34:741–745. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris T, Harris RC, Swain J, Corbett J, Collard K, Dyson RJ, Dye L, Hodgson C, Draper N. Effect of creatine supplementation and sleep deprivation, with mild exercise, on cognitive and psychomotor performance, mood state, and plasma concentrations of catecholamines and cortisol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0269-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel S, Clark JP, Ding JM, Colwell CS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin receptors modulate glutamate-induced phase shifts of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1109–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen KA, Prickaerts J, Steinbusch HW. The dorsal raphe nucleus and serotonin: implications for neuroplasticity linked to major depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Brain Res. 2008;172:233–264. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00912-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima K, Tozawa T, Satoh K, Matsumoto Y, Hishikawa Y, Okawa M. Melatonin secretion rhythm disorders in patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type with disturbed sleep-waking. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:417–421. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima K, Okawa M, Hozumi S, Hishikawa Y. Supplementary administration of artificial bright light and melatonin as potent treatment for disorganized circadian rest-activity and dysfunctional autonomic and neuroendocrine systems in institutionalized demented elderly persons. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:419–432. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra T, Chaudhuri KR. Sleep dysfunction and role of dysautonomia in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord Suppl. 2009;3:S93–S95. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T, Miyamoto M, Inoue Y, Usui Y, Suzuki K, Hirata K. Reduced cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2006;67:2236–2238. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249313.25627.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte-Silva K, Kuo MF, Thirugnanasambandam N, Liebetanz D, Paulus W, Nitsche MA. Dose-Dependent Inverted U-Shaped Effect of Dopamine (D2-Like) Receptor Activation on Focal and Nonfocal Plasticity in Humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6124–6131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0728-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti JM, Monti D. The involvement of dopamine in the modulation of sleep and waking. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:113–133. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montplaisir J, Petit D, Lorrain D, Gauthier S, Nielsen T. Sleep in Alzheimer’s disease: further considerations on the role of brainstem and forebrain cholinergic populations in sleep-wake mechanisms. Sleep. 1995;18:145–148. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.3.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY. Principles of synaptic transmission. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;695:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes Wdos S, Poyares DR, Guilleminault C, Ramos LR, Bertolucci PH, Tufik S. The effect of donepezil on sleep and REM sleep EEG in patients with Alzheimer disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Sleep. 2006;29:199–205. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M, Lynch CA, Walsh C, Coen R, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Sleep disturbance in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. 2005;6:347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muijsers RB, Plosker GL, Noble S. Sertraline: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder in elderly patients. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:377–392. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhrer T. Neurotransmitter systems involved in learning and memory in the rat: a meta-analysis based on studies of four behavioral tasks. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;41:268–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo N, Zhu J, Zhu Y, Fenik P, Lian J, Galante R, Veasey S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in wake-active neurons progresses with aging. Aging Cell. 2011;10:640–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RL, Guo Z, Halagappa VM, Pearson M, Gray AJ, Matsuoka Y, Brown M, Martin B, Iyun T, Maudsley S, Clark RF, Mattson MP. Prophylactic treatment with paroxetine ameliorates behavioral deficits and retards the development of amyloid and tau pathologies in 3xTgAD mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;205:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ, Monteggia LM. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu SF, Chung MH, Chen CH, Hegney D, O’Brien A, Chou KR. The effect of shift rotation on employee cortisol profile, sleep quality, fatigue, and attention level: a systematic review. J Nurs Res. 2011;19:68–81. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e31820c1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi Y, Okamoto N, Uchida K, Iyo M, Mori N, Morita Y. Daily rhythm of serum melatonin levels and effect of light exposure in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Biol Psychiat. 1999;45:1646–1652. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese JM, Cao C, Mori T, Mamcarz MB, Maxwell A, Runfeldt MJ, Wang L, Zhang C, Lin X, Zhang G, Arendash GW. Protection against cognitive deficits and markers of neurodegeneration by long-term oral administration of melatonin in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:82–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:591–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AM, DeKosky ST. Monoamine neurons in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;91:135–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01245229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parachikova A, Nichol KE, Cotman CW. Short-term exercise in aged Tg2576 mice alters neuroinflammation and improves cognition. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postuma RB, Lanfranchi PA, Blais H, Gagnon JF, Montplaisir JY. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2304–2310. doi: 10.1002/mds.23347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RE, Struble RG, Casanova MF, O’Connor DT, Kitt CA, Price DL. Innervation of human hippocampus by noradrenergic systems: normal anatomy and structural abnormalities in aging and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1988;25:401–417. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pungor K, Papp M, Kékesi K, Juhász G. A novel effect of MPTP: the selective suppression of paradoxical sleep in cats. Brain Res. 1990;525:310–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90880-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu WM, Huang ZL, Xu XH, Matsumoto N, Urade Y. Dopaminergic D1 and D2 receptors are essential for the arousal effect of modafinil. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8462–8469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1819-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu WM, Xu XH, Yan MM, Wang YQ, Urade Y, Huang ZL. Essential role of dopamine D2 receptor in the maintenance of wakefulness, but not in homeostatic regulation of sleep, in mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4382–4389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4936-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riederer P, Bartl J, Laux G, Grünblatt E. Diabetes type II: a risk factor for depression-Parkinson-Alzheimer? Neurotox Res. 2011;19:253–265. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. Arousal systems and attentional processes. Biol Psychol. 1997;45:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(96)05222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romberg C, Mattson MP, Mughal MR, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM. Impaired attention in the 3xTgAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: rescue by donepezil (Aricept) J Neurosci. 2011;31:3500–3507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5242-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romigi A, Placidi F, Peppe A, Pierantozzi M, Izzi F, Brusa L, Galati S, Moschella V, Marciani MG, Mazzone P, Stanzione P, Stefani A. Pedunculopontine nucleus stimulation influences REM sleep in Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:e64–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rye D. Seeing beyond one’s nose: sleep disruption and excessive sleepiness accompany motor disability in the MPTP treated primate. Exp Neurol. 2010;222:179–180. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RV, Tufik S, De Mello MT. Exercise, sleep and cytokines: is there a relation? Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Katshu MZ, Nizamie SH, Praharaj SK. Slow wave sleep deficits as a trait marker in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;124:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders NL, Summers MJ. Attention and working memory deficits in mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32:350–357. doi: 10.1080/13803390903042379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. REM behavior disorder (RBD): delayed emergence of parkinsonism and/or dementia in 65% of older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic RBD, and an analysis of the minimum & maximum tonic and/or phasic electromyographic abnormalities found during REM sleep. Sleep. 2003;26:A316Abs. [Google Scholar]

- Seamans JK, Yang CR. The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrill DL, Kotchou K, Quan SF. Association of physical activity and human sleep disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1894–1898. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siderowf A, Jennings D. Cardiac denervation in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson’s disease: getting to the heart of the matter. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2269–2271. doi: 10.1002/mds.23404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene DJ, Swaab DF. Melatonin rhythmicity: effect of age and Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterniczuk R, Antle MC, Laferla FM, Dyck RH. Characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: part 2. Behavioral and cognitive changes. Brain Res. 2010;1348:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranahan AM, Lee K, Martin B, Maudsley S, Golden E, Cutler RG, Mattson MP. Voluntary exercise and caloric restriction enhance hippocampal dendritic spine density and BDNF levels in diabetic mice. Hippocampus. 2009;19:951–961. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Karlsen KA. community-based study of sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1998;13:895–899. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasali E, Leproult R, Spiegel K. Reduced sleep duration or quality: relationships with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TN, Caudle WM, Shepherd KR, Noorian A, Jackson CR, Iuvone PM, Weinshenker D, Greene JG, Miller GW. Nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease revealed in an animal model with reduced monoamine storage capacity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8103–8113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1495-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Neurodegeneration in normal brain aging and disease. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004 Jun 9;2004(23):pe26. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2004.23.pe26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Lai YY, Siegel JM. Hypocretin (orexin) cell loss in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:1586–1595. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunematsu T, Kilduff TS, Boyden ES, Takahashi S, Tominaga M, Yamanaka A. Acute optogenetic silencing of orexin/hypocretin neurons induces slow-wave sleep in mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10529–10539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0784-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S, Ahl M, Cho HH, Bandyopadhyay S, Cuny GD, Bush AI, Goldstein LE, Westaway D, Huang X, Rogers JT. RNA therapeutics directed to the non coding regions of APP mRNA, in vivo anti-amyloid efficacy of paroxetine, erythromycin, and N-acetyl cysteine. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:221–227. doi: 10.2174/156720506777632835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RS. Idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder is a harbinger of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002;15:195–199. doi: 10.1177/089198870201500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger MM, Belke M, Menzler K, Heverhagen JT, Keil B, Stiasny-Kolster K, Rosenow F, Diederich NJ, Mayer G, Möller JC, Oertel WH, Knake S. Diffusion tensor imaging in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder reveals microstructural changes in the brainstem, substantia nigra, olfactory region, and other brain regions. Sleep. 2010;33:767–773. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.6.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Someren EJ, Hagebeuk EE, Lijzenga C, Scheltens P, de Rooij SE, Jonker C, Pot AM, Mirmiran M, Swaab DF. Circadian rest-activity rhythm disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:259–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhave PS, Jongsma MJ, Van den Berg RM, Vis JC, Vanwersch RA, Smit AB, Van Someren EJ, Philippens IH. REM Sleep Behavior Disorder in the Marmoset MPTP Model of Early Parkinson Disease. Sleep. 2011;34:1119–1125. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello MV, Prinz PN, Williams DE, Frommlet MS, Ries RK. Sleep disturbances in patients with mild-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M131–8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.4.m131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A. Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:704–711. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LC, Levine H, 3rd, Mattson MP, Jucker M. Inducible proteopathies. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ho L, Qin W, Rocher AB, Seror I, Humala N, Maniar K, Dolios G, Wang R, Hof PR, Pasinetti GM. Caloric restriction attenuates beta-amyloid neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3182fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:342–345. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisor JP, Edgar DM, Yesavage J, Ryan HS, McCormick CM, Lapustea N, Murphy GM., Jr Sleep and circadian abnormalities in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: a role for cholinergic transmission. Neuroscience. 2005;131:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YH, Swaab DF. Disturbance and strategies for reactivation of the circadian rhythm system in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. 2007;8:623–636. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YH, Zhou JN, Van Heerikhuize J, Jockers R, Swaab DF. Decreased MT1 melatonin receptor expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Friedman L, Kraemer H, Tinklenberg JR, Salehi A, Noda A, Taylor JL, O’Hara R, Murphy G. Sleep/wake disruption in Alzheimer’s disease: APOE status and longitudinal course. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:20–24. doi: 10.1177/0891988703261994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zant JC, Leenaars CH, Kostin A, Van Someren EJ, Porkka-Heiskanen T. Increases in extracellular serotonin and dopamine metabolite levels in the basal forebrain during sleep deprivation. Brain Res. 2011;1399:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Veasey SC, Wood MA, Leng LZ, Kaminski C, Leight S, Abel T, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Impaired rapid eye movement sleep in the Tg2576 APP murine model of Alzheimer’s disease with injury to pedunculopontine cholinergic neurons. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61223-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond MJ, Cameron JL, Leak RK, Mirnics K, Russell VA, Smeyne RJ, Smith AD. Triggering endogenous neuroprotective processes through exercise in models of dopamine deficiency. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(Suppl 3):S42–45. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]