Abstract

Although clinical preventive services (CPS)—screening tests, immunizations, health behavior counseling, and preventive medications—can save lives, Americans receive only half of recommended services. This "prevention gap," if closed, could substantially reduce morbidity and mortality. Opportunities to improve delivery of CPS exist in both clinical and community settings, but these activities are rarely coordinated across these settings, resulting in inefficiencies and attenuated benefits. Through a literature review, semi-structured interviews with 50 national experts, field observations of 53 successful programs, and a national stakeholder meeting, a framework to fully integrate CPS delivery across clinical and community care delivery systems was developed. The framework identifies the necessary participants, their role in care delivery, and the infrastructure, support, and policies necessary to ensure success.

Essential stakeholders in integration include clinicians; community members and organizations; spanning personnel and infrastructure; national, state, and local leadership; and funders and purchasers. Spanning personnel and infrastructure are essential to bring clinicians and communities together and to help patients navigate across care settings. The specifics of clinical–community integrations vary depending on the services addressed and the local context. Although broad establishment of effective clinical–community integrations will require substantial changes, existing clinical and community models provide an important starting point. The key policies and elements of the framework are often already in place or easily identified. The larger challenge is for stakeholders to recognize how integration serves their mutual interests and how it can be financed and sustained over time.

Introduction

Despite widespread agreement about the benefits and economic value of effective clinical preventive services (CPS),1–4 Americans receive only half of recommended care.5,6 For example, as recently as 2010, large proportions of Americans were overdue for colorectal cancer screening (47%); influenza (28%) and pneumococcal (33%) vaccinations; and screening mammography (22%).7 From 1999 to 2004, only 25% of adults aged 50–64 years were up to date on all indicated high-priority services.8,9 This gap in preventive care is more pronounced among low-income Americans, racial and ethnic minorities, and older adults.10

Decades of interventions and policies focused on improving CPS delivery in the clinical setting have achieved modest success. Efforts have included reminder systems, removal of patient financial barriers, patient and clinician education, first-dollar coverage of preventive services, and practice and health system redesign.11–13 Another strategy to enhance CPS delivery is to shift delivery into the community, reaching people where they live, work, learn, and play.14

Community engagement in CPS is neither new nor unevaluated.15,16 For decades, media campaigns initiated by public health agencies and community organizations have raised awareness about critical services such as cervical, colorectal, and breast cancer screening. Access to colorectal and breast cancer screening has been made available at community flu-shot clinics, and vaccinations have been administered in pharmacies, churches, and polling places.3,17–20 State health departments have operated smoking-cessation quitlines.18 Lay health workers based in the community have also promoted CPS.21,22 Yet the community, acting alone, cannot be effective in improving delivery of clinical preventive services without the collaboration of the medical community.

Delivery of CPS might be more effective if the efforts of clinical and community systems are coordinated to promote their use. Such a partnership is a logical extension of shared interest in prevention and population health. Better outcomes have been documented when clinicians initiate care, and community programs provide intensive assistance and follow-up, than when clinicians and communities address CPS in silos.23,24

Such collaboration is useful to promote screening tests and immunizations, but moving outside the clinic is essential to meaningfully address lifestyle issues. The socioecologic model of health, and the behavioral science literature, demonstrates that personal choices are heavily influenced by broader social, economic, cultural, health, and environmental conditions.25–28 Clinician counseling to change lifestyle cannot realistically be effective without being coordinated with efforts in the community to create living conditions that support healthier choices. The medical community is part of a larger community ecosystem involving multiple sectors that, by working together, can achieve “citizen-centered” approaches to such conditions as tobacco use, obesity, and other modifiable risk factors.29

Streamlining parallel delivery systems would also be expected to increase efficiency and thereby contribute to the “triple aim” of controlling costs along with improving the patient care experience and population health.30 The inherent logic of this argument was recognized 2 decades ago, notably by the leaders of the Medicine and Public Health Initiative31 and subsequent calls for action,32 and recent years have brought increasing calls to integrate clinical and community care systems.33,34 However, the field can point to only a handful of working models of such integrations with published evidence of improved quality of care or health outcomes.35

Many blue-ribbon panels are arguing that now is the time to broadly establish clinical–community integrations.36,37 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) called for reorienting health systems toward increased integration through the formation of accountable care organizations,13 but commentators note the need for integration with the community to successfully improve population health.38,39 Primary care specialties have embraced the concept of the patient-centered medical home, or what was once called community-oriented primary care.12

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act invested in an electronic architecture that can link information systems across clinical and community care settings.40 This concept of broadly integrating public health and primary care was advocated in a recent IOM report.13,36 Integration also provides an architecture to build on the growing movement in active stakeholder engagement—of patients as engaged partners in shaping their care experience and of the community as partners in improving public health—and provides a vehicle for bringing these threads together.41–45 Payment reforms to shift traditional fee-for-service reimbursements to global risk-based payments for improved outcomes offer a potential financial model for clinical–community integrations.

What is the next step? How might everyday clinical and community organizations establish and sustain a local model for integrating care and apply it to prevention?46,47 Multiple national organizations and thought leaders are currently developing a strategic plan to provide the answers. The current paper describes a conceptual framework that suggests how clinicians and community organizations might integrate care on a national scale and apply it to prevention.

Methods

The CDC’s Healthy Aging Program issued two major reports identifying a substantial deficiency in CPS uptake among older Americans.43,44 Under the auspices of the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, guided discussions with 25 national experts on prevention were conducted to understand the opportunities and challenges to increase the use of CPS among adults age 50 and older. A recurrent theme that emerged from the interviews was the need for integrating the extant clinical and community infrastructure for more effective CPS delivery.

The integration framework proposed in the current paper evolved from a series of inter-related efforts, including a literature review of care delivery models (e.g., Sickness Prevention Achieved Through Regional Collaboration [SPARC] model; Chronic Care Model; and a variant for prevention proposed by Glasgow),34,48–50 as well as evidence-based strategies to promote preventive services (including clinical, community, and clinical–community interventions); guided interviews with, or field observations of, 53 successful clinical– community integrations51; a national stakeholder meeting with representatives from 33 organizations (see the Acknowledgements section) to present and review a preliminary draft framework; framework revision by the authors to incorporate stakeholder perspectives; and stakeholder review of the revised framework.

Clinical–Community Integration Framework

Outlining the Stages of Preventive Services Delivery

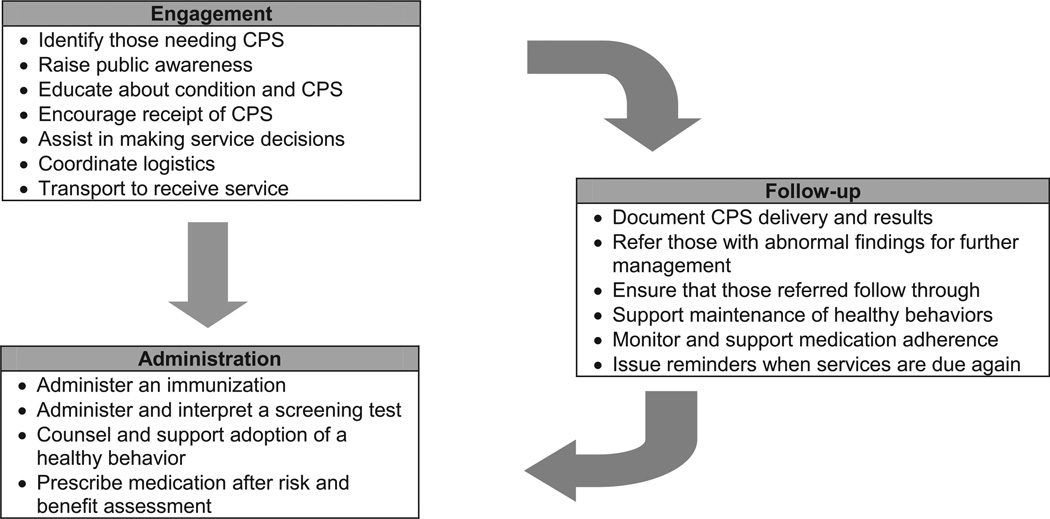

Clinical preventive services are often defined as screening tests, immunizations, health behavior counseling, and preventive medications.1 But prevention is more than simply ordering a test, administering an immunization, counseling a patient, or prescribing a medication. Effective delivery requires much more, including (1) engaging individuals in need of services; (2) administering the CPS; and (3) following up (Figure 1).52

Figure 1.

Stages of preventive care delivery

Note: Preventive care is more than just administering a service; it includes three key components: engagement, administration, and follow-up.

CPS, clinical preventive services

Engagement encompasses all that is necessary before administration, such as identifying individuals who need services, motivating them to receive the service, and coordinating delivery. Administration includes giving a vaccine or screening test, counseling a patient, or prescribing chemoprevention. Follow-up is what should occur after administration, including (1) immediate actions (e.g., documenting delivery in medical records, referring individuals with abnormal results for evaluation and management, ensuring that individuals follow through with recommended management); (2) long-term support to maintain healthy behaviors and medication adherence; and (3) continued reassessment to identify and reengage individuals when they relapse or are next due for services.

Current performance assessment and reimbursement initiatives for preventive services focus on the act of administration, often to the neglect of engagement, follow-up, and attention to the environment that shapes health behaviors. Yet these steps may be the most critical to improve current CPS delivery and effectiveness. Strategies to increase CPS delivery should consider all of these factors, and models for clinical–community integrations are no exception.

Principles of Integration

Although the specifics of clinical–community integrations will vary depending on the services addressed and on local context, certain defining characteristics exemplify an integrated delivery model. By definition, the clinical and community entities must both participate in at least one part of the CPS engagement/administration/follow-up process. Ideally, activities and resources should be coordinated and appropriately shared. An integrated delivery system should meet certain standards, including being accountable for the CPS delivered to a broad community-based population, acceptable to all participants and recipients, accessible and affordable, and coordinated between participants and other healthcare providers.

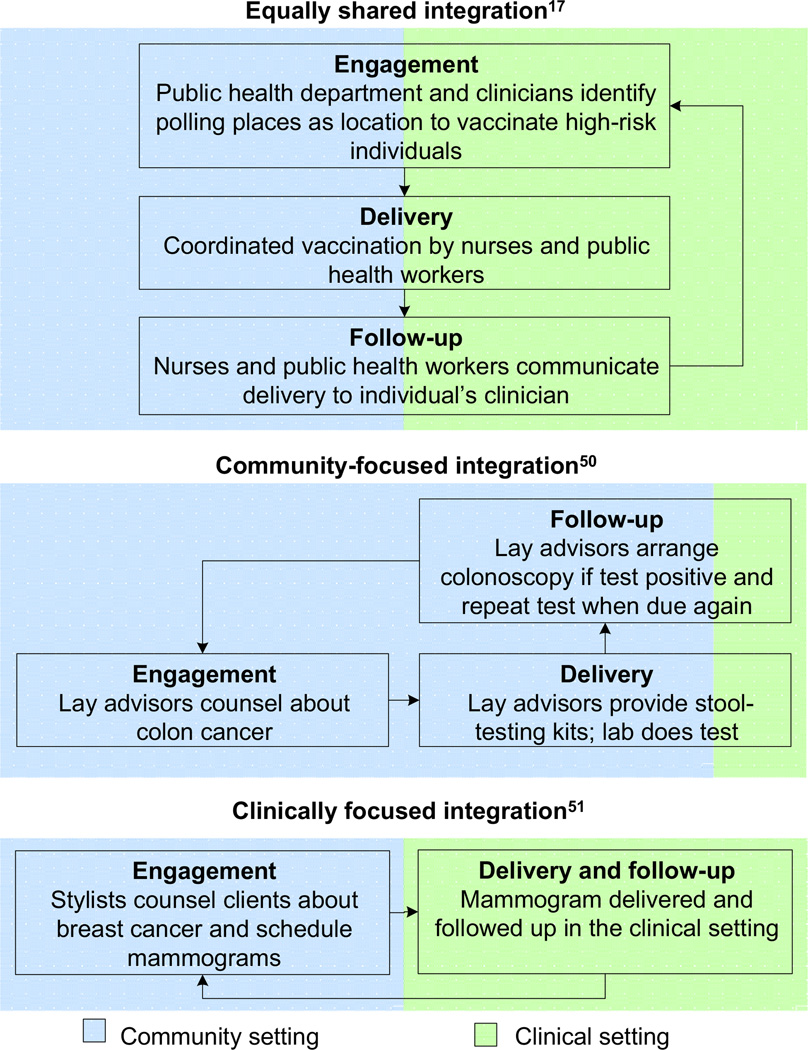

The degree of integration across community and clinical settings will also vary for programs. Figure 2 highlights an example of an integration in which the community and clinical partners participate equally in each step of the CPS delivery process.18 Effective integrations can also have a primary community or a clinical focus (Figure 2, lower panels) and still be considered “integrated” as long as the integration adheres to the distinguishing characteristics outlined above.53,54 These examples are fundamentally different from the current often non-integrated “silo” model, a healthcare system in which pharmacies give immunizations without notifying the customer’s clinician or clinicians focus on patients who visit their practice without attention to those who stay home (e.g., do not send reminders regarding CPS).

Figure 2.

Continuum of clinical–community integration

Framework for Integration

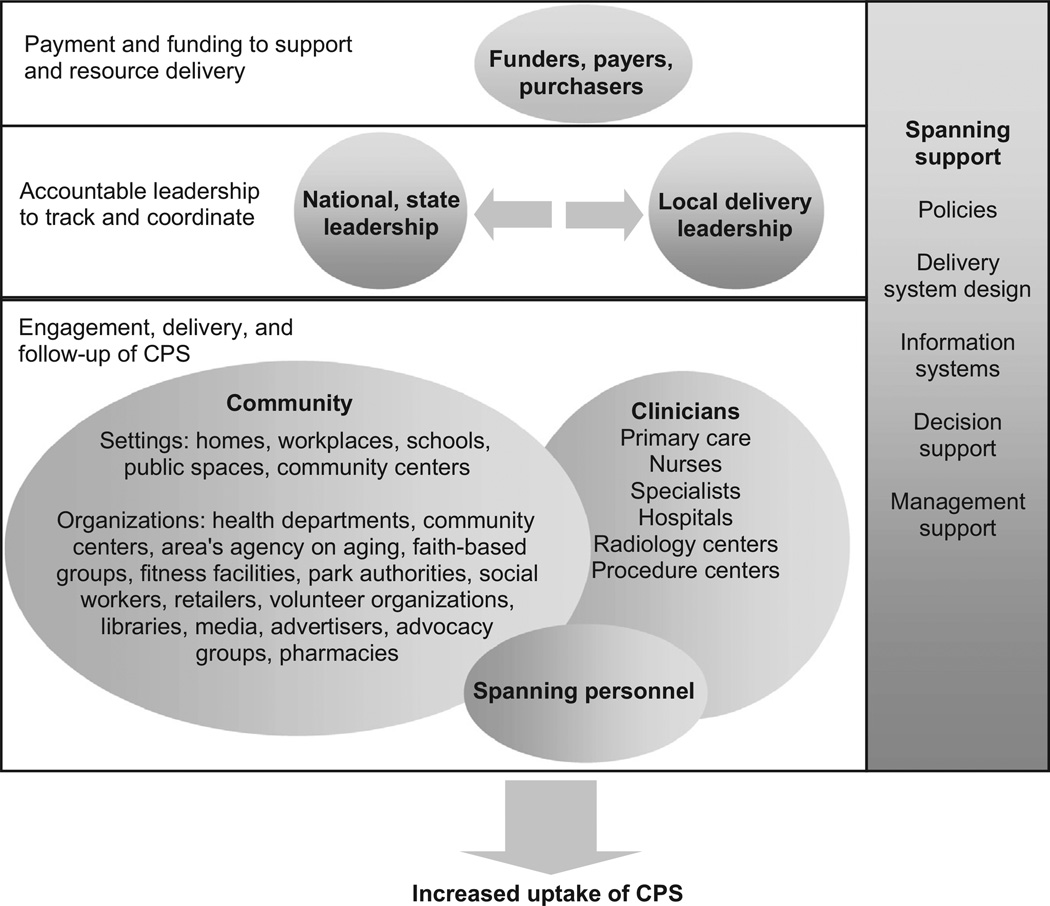

Clinical–community integration is most successful when all key stakeholders are engaged. The framework recognizes six critical stakeholder groups: (1) clinicians; (2) community members and organizations; (3) spanning personnel and infrastructure; (4) national and/or state leadership; (5) local leadership; and (6) funders and purchasers (Figure 3). Clinician participants include all clinical entities required for prevention—primary care providers, specialist physicians, nurses, radiology centers, laboratories, hospitals, and procedure centers. Although clinicians can participate in all three steps of the CPS delivery process, their unique role lies in conducting (e.g., performing a colonoscopy); interpreting (e.g., examining a mammogram); and following up (e.g., addressing identified abnormal screening results) on CPS.

Figure 3.

A framework to integrate clinical and community care for CPS

Note: Funders, payers, and purchasers are tasked with financing the infrastructure needed for integration and preventive care. National and state leadership are empowered with the authority, resources, and responsibility to foster integrations across regions. Local leaders are the regional organizations that step forward to oversee and support local tailoring, integration activities, and CPS delivery. Community is the setting where individuals live, work, and play and where the stakeholders who serve them are located. Community organizations are care providers that deliver the community elements of the clinical–community integration. Clinicians are care providers that deliver the clinical elements of the clinical–community integration. Spanning personnel are staff who specialize in helping people traverse the clinical and community settings to obtain CPS. Spanning support (which includes policies, delivery system design, information systems, decision support, and management support) are essential ingredients to support integrations at all three levels depicted in the diagram.

CPS, clinical preventive services

Additionally, clinicians can contextualize CPS in relation to a patient’s complete health history and problem list. Patients frequently cite clinician advice as a key reason they obtained CPS.55,56 The patient-centered medical home is a natural focal point for involving clinicians in an integrated approach to CPS delivery. Patient-centered medical homes retain the historical strengths of primary care in addressing diverse health needs with a focus on prevention, but they also embrace the application of advanced information technology, team-based care, infrastructure to coordinate care, population management, and the overarching goal of improving the health of an entire population of patients.57–59

The community includes the settings in which individuals live, work, learn, and play, as well as the organizations that serve them. Like clinicians, community members and organizations can effectively participate in all aspects of the CPS delivery process but may be uniquely positioned to engage patients and provide ongoing assistance and follow-up over time. Often individuals most in need of CPS interact little with clinicians, potentially because they lack motivation, access, or awareness of a need. Communities offer an attractive venue for engagement, as exemplified by the success of lay health workers in identifying and motivating individuals in need of CPS.54,60–63

As noted above, the lifestyle changes that clinicians and others recommend must occur outside the clinic, in the community settings where people encounter opportunities and barriers to physical activity, healthy diets, smoking cessation, and other healthy behaviors. Clinicians and communities require “spanning” support to bridge geographic and institutional boundaries of organizations with disparate missions. The term “spanning support” refers to the arrangements, processes, tools, resources, information systems, and surveillance data required for clinical–community integrations. In the clinically oriented Chronic Care Model, this support is labeled the “health system” and includes many of the same functions.48 However, in a clinical–community integration, spanning support needs to be extended beyond the clinic to the community and even to local and national/state leaders, funders, and payers. The latter groups particularly need access to surveillance data to help guide population-level decisions.36

Spanning personnel act as the glue that bonds the community and clinical systems, serving as a shared resource to promote communication between settings and to help individuals navigate care delivery across the continuum of care. Examples include community coordinators, care managers, and patient navigators.64–67 By definition, spanning personnel are accessible to and familiar with all domains of CPS delivery and can interact with all participants. Numerous examples demonstrate their importance in improving the care experience, improving population health, and lowering costs (e.g., Vermont’s Blueprint for Health, Community Care of North Carolina, and the Virginia Coordinated Care program).65,68,69

National and state leaders are important champions who can bring energy and resources to launch and sustain integrated care delivery (Figure 3). Leaders can inspire the guiding principles to model clinical–community integrations, provide the statutory authority and resource streams to ensure that integrations are sustained across regions, and catalyze national partnerships to advance and support local integrations. Governmental leadership may be needed to accomplish some of these tasks, but leadership can also come from private organizations, coalitions organized by state agencies (e.g., Vermont’s Blueprint for Health),65 and proposed new entities (e.g., Wellness Trust).70 For example, in 2012, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), and UnitedHealth Group convened multiple national organizations and agencies that together developed a strategic map (Figure 3) for achieving the fuller integration of primary care and public health. Many organizations have moved forward with action steps with their members and constituencies to implement the strategic plan.

Although national and state leadership can be influential, local needs and resources vary from community to community, and a one-size-fits-all model for integration cannot be implemented. Local tailoring is essential to identify regional needs and resources, obtain buy-in from stakeholders, bring stakeholders together to reach agreement on roles and processes for engagement/administration/ follow-up, coordinate activities to avoid duplication and ensure the seamless transition of care between participants, and track CPS uptake for the region.

Local leadership is an important coordinating entity to perform these tasks. Organizations that function as local leaders often know all participants involved with local CPS delivery and possess resources to catalyze integration activities. Examples include public health organizations (e.g., local health departments); clinical entities (e.g., healthcare systems, medical societies); or community organizations (e.g., area agencies on aging, YMCA). One successful example of local leadership is an initiative of the SPARC community health organization, which coordinates clinicians and multiple community stakeholders (e.g., on Election Day, SPARC works with local officials to provide influenza vaccinations at polling places).18,71

Finally, collaboration and support from funders, payers, and purchasers are needed to ensure that the costs of operating the integrated model are adequately resourced. Funding organizations (e.g., state and national government, foundations) can provide infrastructure support through grants and program funding. Payers can reimburse delivery of CPS in clinical and community settings. Purchasers (e.g., employers) can persuade insurers to include such coverage in their benefits package. The capital costs of establishing and maintaining an infrastructure for integration are not trivial, but they can potentially be recouped by integrating and leveraging existing resources, avoiding duplication of services, and thereby creating a more efficient delivery system.72

What Will It Take to Implement Clinical Community Integrations?

Although creating an effective integrated clinical–community care system will require substantial changes, it is possible to build on existing clinical and community platforms to augment delivery of preventive care without undermining the role of clinicians or existing programs. There is substantial national interest and a palpable momentum to create clinical–community integrations. Policies and other elements of the framework are already in place, but the field is now turning to specific next steps for scalability to move beyond exemplar and pilot programs.

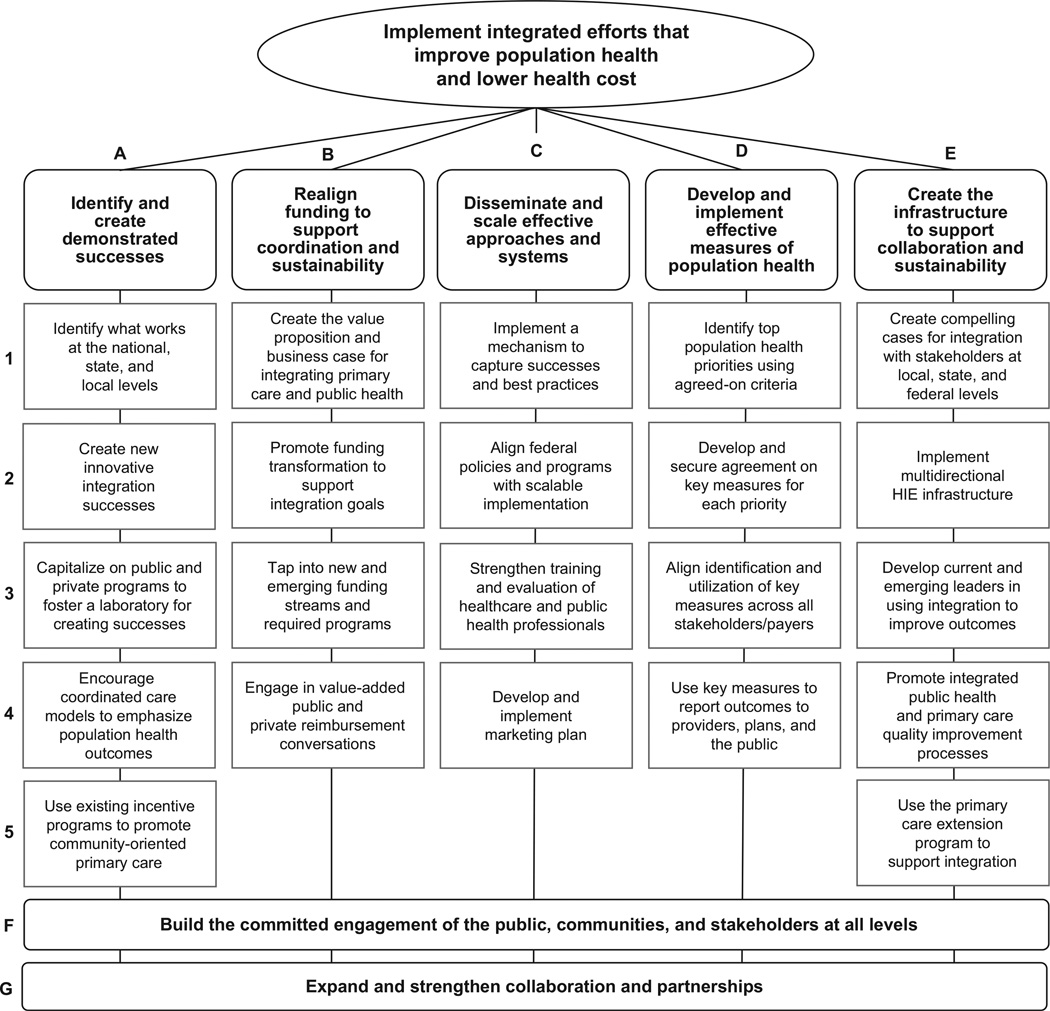

For example, the coalition of organizations organized by ASTHO, the UnitedHealth Group, IOM, the CDC, and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) have created seven teams to identify demonstrated successes, realign funding to support coordination and sustainability, disseminate and scale effective approaches, develop effective measures for tracking progress, and create the infrastructure to support collaboration, build the commitment of the public, communities, and stakeholders at all levels, and expand partnerships (Figure 4).73

Figure 4.

Primary care and public health integration strategic map, 2012–2014

Note: This strategic plan for national progress in integrating medicine and public health was developed at a July 2012 meeting of major organizations and government agencies convened jointly by ASTHO and the IOM with support from United Health Foundation, the CDC, and the Health Resources and Services Administration. The map was produced by the participants and does not reflect the views of the sponsoring organizations. More about the ASTHO initiative and the steps medical and public health organizations are taking nationwide to implement the strategic plan can be found at www.astho.org/Programs/Access/Primary-Care-and-Public-Health-Integration/.

ASTHO, Association of State and Territorial Health Officers; HIE, health information exchange

What is emerging from these efforts is a crowded action agenda at the national, state, and local levels.37,73–76 National organizations such as those listed above, with growing support from major medical societies and payer groups, are actively discussing integration designs that have realistic business models,73 but some of the most exciting experiments in integration are occurring at the state and local levels.

To achieve success in these efforts, local officials and the managers of health systems must build a public constituency for the hard work entailed by identifying how integration aligns with the interests of stakeholders and how it can be financed and sustained over time. Whether integration makes sense is no longer the question, but rather how to achieve scalability and sustainability. Ongoing evaluation will be needed to more clearly define more effective models for clinical–community integration, the circumstances in which they work, and the potential for unintended consequences.

Conclusion

Just as U.S. society is committed to caring for acute and chronic illnesses, a similar commitment for prevention is important. Greater success in preventing disease through collaboration may not only save lives but may also reduce disease burden and thereby help curb the rising costs of health care. There may be challenges in operationalizing a model that proposes to engage clinicians and community organizations, spanning personnel, national and state leaders, local leadership, and funders, payers, and purchasers. Some steps may be implemented now, but others will require long-term strategic planning. The infrastructure for collaboration is rapidly taking form through development of communication systems and informatics, which have the potential to help make clinical–community integration a reality. Given the national efforts to expand coverage of CPS and to test innovations to promote quality health care,75 developing and implementing new clinical–community integration models is of critical importance.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by Grant/Cooperative Agreement Number U58DP002759-01 from the CDC to National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD) and Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI). Work was also supported by the CTSA Grant Number ULTR00058 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CDC, NACDD, MPHI, or NCATS. The authors specially acknowledge Peter Briss, MD, MPH, Steven Wallace, PhD, and Kathryn Keitzman, PhD, for collaborative efforts interviewing successful clinical–community intervention participants and/or reviewing manuscripts.

The authors thank the individuals and organizations that participated in a stakeholder meeting to provide input on the proposed framework, including the American Association for Retired Persons (AARP); Administration on Aging; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; American College of Preventive Medicine; American Medical Association; American Pharmacist Association; Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; Atlanta Regional Commission; CDC; CMS; DHHS; Health Resources and Services Administration; John Hartford Foundation; Los Angeles Public Health Department; National Association of Chronic Disease Directors; National Association of Community Health Centers; National Association of County and City Health Officials; National Council on Aging; Partnership for Prevention; University of Georgia; University of Washington; Virginia Commonwealth University; Wellmed Foundation; and the YMCA.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Preventive Services. 2012 www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm.

- 2.Recommendation and Guidelines: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) 2010 www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/ACIP/default.htm.

- 3.Guide to Community Preventive Services. 2011 www.thecommunity guide.org/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden TR. Use of selected clinical preventive services among adults—U.S., 2007–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(S):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the U.S.N. Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. BRFSS—CDC's behavioral risk factor surveillance system. 2010 www.cdc.gov/brfss.

- 8.Shenson D, Bolen J, Adams M. Receipt of preventive services by elders based on composite measures, 1997–2004. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shenson D, Adams M, Bolen J. Delivery of preventive services to adults aged 50–64: monitoring performance using a composite measure, 1997–2004. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):733–740. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0555-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DHHS. Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington DC: Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The National Prevention Strategy. 2011 www.healthcare.gov/center/councils/nphpphc/index.html.

- 12.Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2009 www.pcpcc.net/. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law. (2nd Session ed) 2010:111–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shenson D. Putting prevention in its place: the shift from clinic to community. Health Affairs. 2006;25(4):1012–1015. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The compendium of proven community-based prevention programs. 2011 healthyamericans.org/report/66/prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin-Misener R. The strengthening primary health care through primary care and public health collabortion research team. A scoping literature review of collaboration between primary care and public health. 2009 doi: 10.1017/S1463423611000491. www.swchc.on.ca/documents/MartinMisener-Valaitis-Review.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shenson D, Adams M. The Vote and Vax program: public health at polling places. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(5):476–480. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333883.52893.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potter MB, Phengrasamy L, Hudes ES, McPhee SJ, Walsh JM. Offering annual fecal occult blood tests at annual flu shot clinics increases colorectal cancer screening rates. Ann Family Med. 2009;7:17–23. doi: 10.1370/afm.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shenson D, Cassarino L, DiMartino L, et al. Improving access to mammograms through community-based influenza clinics: a quasi-experimental study. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry MB, Saul J, Baily LA. U.S. quitlines at a crossroads: utilization, budget, and service trends 2005–2010. 2010 www.naquitline.org/resource/resmgr/reports_2010/100407_special-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien MJ, Halbert CH, Bixby R, Pimentel S, Shea JA. Community health worker intervention to decrease cervical cancer disparities in Hispanic women. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1186–1192. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krist AH, Woolf SH, Frazier CO, et al. An electronic linkage system for health behavior counseling effect on delivery of the 5A's. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5S):S350–S358. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolf SH, Glasgow RE, Krist A, et al. Putting it together: finding success in behavior change through integration of services. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3S2:S20–S27. doi: 10.1370/afm.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IOM. For the public's health: investing in a healthier future. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2012. Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownell KD, Kersh R, Ludwig DS, et al. Personal responsibility and obesity: a constructive approach to a controversial issue. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):379–387. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health social behavior. 1995;(Spec No):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:5–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woolf SH, Dekker MM, Byrne FR, Miller WD. Citizen-centered health promotion: building collaborations to facilitate healthy living. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1S1):S38–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasker RD. Medicine & public health: the power of collaboration. Chicago IL: Health Administration Press; 1997. New York Academy of Medicine. Committee on Medicine and Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis RM. Marriage counseling for medicine and public health: strengthening the bond between these two health sectors. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woolf SH, Krist AH, Rothemich SF. Joining hands: partnerships between physicians and the community in the delivery of preventive care. Washington DC: Center for American Progress; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shenson D, Benson W, Harris AC. Expanding the delivery of clinical preventive services through community collaboration: the SPARC model. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porterfield DS, Hinnant LW, Kane H, Horne J, McAleer K, Roussel A. Linkages between clinical practices and community organizations for prevention: a literature review and environmental scan. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S3):S375–S382. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.IOM. Primary care and public health: exploring integration to improve population health. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landon BE, Grumbach K, Wallace PJ. Integrating public health and primary care systems: potential strategies from an IOM report. JAMA. 2012;308(5):461–462. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noble DJ, Casalino LP. Can accountable care organizations improve population health?: Should they try? JAMA. 2013;309(11):1119–1120. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shortell SM. Bridging the divide between health and health care. JAMA. 2013;309(11):1121–1122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. HITECH Programs. 2012 healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=1487&mode=2.

- 41.Fleurence R, Selby JV, Odom-Walker K, et al. How the patient-centered outcomes research institute is engaging patients and others in shaping its research agenda. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):393–400. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roseman D, Osborne-Stafsnes J, Amy CH, Boslaugh S, Slate-Miller K. Early lessons from four “aligning forces for quality” communities bolster the case for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):232–241. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danis M, Solomon M. Providers, payers, the community, and patients are all obliged to get patient activation and engagement ethically right. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):401–407. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enhancing use of clinical preventive services among older adults. 2011 www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/Clinical_Preventive_Services_Closing_the_Gap_Report.pdf.

- 47.CDC, AARP American Medical Association. Promoting preventive services for adults 50–64: community and clinical partnerships. Atlanta GA: National Association of Chronic Disease Directors; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):579–612. iv–v. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27(2):63–80. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parks AV, Satter DE, Kietzman KG, Wallace SP. Opportunity knocks for public health departments: increasing the use of clinical preventive services by older adults. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. 2012 ( healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/phpnsep2012.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lesser LI, Krist AH, Kamerow DB, Bazemore AW. Comparison between U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations and Medicare coverage. Ann Fam Med. 2010;9(1):44–49. doi: 10.1370/afm.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walsh JM, Terdiman JP. Colorectal cancer screening: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289(10):1288–1296. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson TE, Fraser-White M, Feldman J, et al. Hair salon stylists as breast cancer prevention lay health advisors for African American and Afro-Caribbean women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):216–226. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J. Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2S):61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(S1):S3–S32. doi: 10.1370/afm.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2007 www.pcpcc.net/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart EE, Jaen CR. Summary of the National Demonstration Project and recommendations for the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(S1):S80–S90. S92. doi: 10.1370/afm.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Wu P, Alisangco J, Castaneda SF, Kelly C. A cluster randomized controlled trial to increase breast cancer screening among African American women: the black cosmetologists promoting health program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hart A, Jr, Underwood SM, Smith WR, et al. Recruiting African- American barbershops for prostate cancer education. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(9):1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larkey LK, Herman PM, Roe DJ, et al. A cancer screening intervention for underserved Latina women by lay educators. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(5):557–566. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WestRasmus EK, Pineda-Reyes F, Tamez M, Westfall JM. Promotores de salud and community health workers: an annotated bibliography. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(2):172–182. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31824991d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grumbach K, Mold JW. A health care cooperative extension service: transforming primary care and community health. JAMA. 2009;301(24):2589–2591. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Vermont's Blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(3):383–386. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.WVU Extention Service. 2011 ext.wvu.edu/. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holtrop JS, Dosh SA, Torres T, Thum YM. The community health educator referral liaison (CHERL): a primary care practice role for promoting healthy behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5S):S365–S372. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ricketts TC, Greene S, Silberman P, Howard HA, Poley S. Evaluation of Community Care of North Carolina Asthma and Diabetes Management Initiatives: January 2000-December 2002. 2004 www.shepscenter.unc.edu/research_programs/health_policy/Access.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bradley CJ, Gandhi SO, Neumark D, Garland S, Retchin SM. Lessons for coverage expansion: a Virginia primary care program for the uninsured reduced utilization and cut costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(2):350–359. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lambrew JL. A wellness trust to prioritize disease prevention. 2007 www.brookings.edu/papers/2007/04useconomics_lambrew.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sickness prevention acheived through regional collaboration. Vote & Vax. 2012 www.voteandvax.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in U.S. health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513–1516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Primary care and public health integration. 2012 www.astho.org/pcph-strategicmap/. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Community health teams issue report. 2012 www.astho.org/Programs/Access/Primary-Care/_Materials/Community-Health-Teams-Issue-Report/. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. The CMS Innovation Center. innovation.cms.gov/.

- 76.CDC. Community transformation grants. www.cdc.gov/communitytransformation/.