Abstract

This report describes the case of a 71-year-old lady who was diagnosed with a Stanford type A dissecting aortic aneurysm which resulted in paraplegia secondary to spinal artery injury at T12 level. She had surgical repair with a tube graft. At a routine review CT scan 2 years postdissection, she presents with asymptomatic but significant dilation, of maximum diameter 78 mm, of the superior part of the ascending thoracic aorta, extending into the arch, suggestive of false aneurysm formation at the surgical anastomoses. There was also thrombosis of the false lumen in the distal arch and descending thoracic aorta. She is a candidate for urgent resection of the aortic arch and reimplantation of the brachiocephalic vessels.

Background

Thoracic aortic aneurysms are relatively uncommon with an incidence of 10.4 per 100 000, occurring mostly in older individuals of either sex;1 conventional treatment is open chest surgical repair with prosthetic grafts; however, there is increasing interest in alternative approaches such as endovascular repair.2

Thoracic aortic aneurysms and their dissections are often asymptomatic, making them difficult to diagnose; they are associated with a high degree or mortality and morbidity.3 The rupture rate is between 80% and 95%4–6) which may be reducible if the genetic basis of aortic disease could be better understood, as reviewed by Hasham et al.7

Although the typical presentation of a dissecting aortic aneurysm is cardiovascular symptoms with acute thoracic or abdominal pain, neurological symptoms at the onset of dissection are frequent in 17–40% of patients.8 Misleading neurological symptoms may result in a delay in dissection diagnosis as well as result in significant future impairments for example, ischaemic neuropathy, nerve compression syndromes, stroke, renal failure etc, as reviewed by Gaul et al.8

Patients who survive dissection and undergo successful surgical repair often have long-term complications. Stent devices have late complications that are particularly pertinent to this case report, including development of leaks, thrombosis of the false lumen9 and subsequent aortic dilation and graft migration; these patients often need reintervention and frequent CT surveillance for early detection of potentially lethal complications. Reoperation carries its own risks for these patients; however, in the majority of cases these procedures carry a low operative risk with good long-term survival.10 Pugliese et al10 suggest more aggressive surgical approach may reduce the incidence of reoperation.

This case highlights the importance of continued close follow-up after aortic dissection surgical repair even in the seemingly asymptomatic patient. It demonstrates the significance of three-dimensional (3D) CT imaging and the insight it can provide in complex patient cases where other imaging techniques, for example, echocardiogram (ECHO), ECG, etc, may not otherwise indicate a clinical concern.

Case presentation

Presenting complaint

The patient is a 71-year-old lady. She is attending a routine out-patient appointment 2 years after surgical repair of an aortic dissection. She is asymptomatic; she denies any chest pain, breathlessness or haemoptysis since her previous appointment.

On examination there are no abnormalities of note; she is haemodynamically stable and heart sounds are normal.

However, routine CT scans at this time demonstrates an aneurysmal dilation of the superior part of the ascending thoracic aorta extending into the arch of maximal transverse diameter 78 mm. CT images are shown in figures 1 and 2.

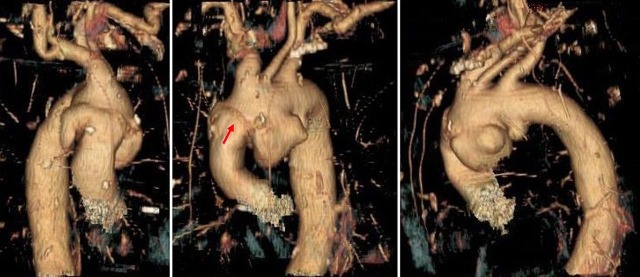

Figure 1.

Several dilations can clearly be seen in the 3D images arising from the inferior border of the aortic arch. There is also evidence of the previous tube graft surgical repair as seen by the suture line (red arrow on central image).

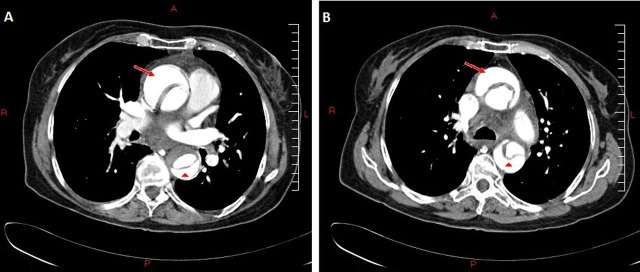

Figure 2.

CT, taken 2011, with contrast in coronal section. The dilation was a maximum of 78mm in diameter. CT analysis also showed the false lumen in the distal arch and descending thoracic was largely thrombosed. The maximal diameter in the distal arch was 42mm, 41mm in the mid descending thoracic aorta, 38mm in the supraceliac aorta and 23mm at the infrarenal aorta (all AP diameters).

History of presentation complaint

When the patient was 69- year-old, she presented to the emergency department on 28 December 2008; she was admitted at 13:00 h after collapsing at home early that morning. She described lower left thoracic pain and severe lower abdominal pain followed by leg weakness. She did not describe ‘tearing’ or ‘ripping’ pain in the chest or interscapular areas and there was no evidence of ‘migratory pain’ as is typically associated with a dissecting aortic aneurysm;11 a neurological cause was initially considered. This led to a delay in the diagnosis of an aortic aneurysm; dissection was considered at 04:00–06:00 h the following morning which was confirmed by CT imaging (figure 3) and she was taken to theatre at 23:00 h that day.

Figure 3.

Transverse CT images taken December 2008 at the time of admission. These show the ascending (red arrow) and descending (red arrow head) aorta with a dissection flap showing a true and false lumen. Two images are shown; one inferior (A) to the other (B). There is also evidence of probable atheroma or thrombosis apparent in the descending aorta (A).

A Stanford type A dissection was confirmed. Surgical repair of the dissection11 was undertaken with a 30 mm Hemashield Gold Knitted Double Velour Vascular Graft (Maquet GmBH & Co, KG, Rastatt, Germany); however, the tissue quality was very poor and required a large amount of surgical adhesive and Teflon buttressing. Haemostasis was predictably difficult. The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) was 14% and logistic EuroSCORE was 49.11%. The patient became significantly hypotensive postprocedure with a cardiac tamponade requiring reopening 6 h later.

Postprocedure, the pulses and touch sensation were intact in both legs, however, the patient remained paraplegic with flaccid paralysis, areflexia and bilateral foot drop consistent with spinal injury at the level of T12.

Postoperative CT scans (not shown) confirmed satisfactory surgical repair of the ascending aorta. The dissection flap was not distinguishable here; it was identifiable at the level of the left subclavian artery and was just patent in the descending thoracic aorta with very sluggish flow but was largely compressed by the true lumen. The true lumen supplied the kidneys, the celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery. Within the abdomen the dissection flap was rather better perfused than in the thorax with the dissection flap extending to the aortic bifurcation and into the right iliac bifurcation.

The patient remained relatively well from a cardiothoracic perspective; however, she was admitted to hospital a number of times over the preceding 2 years with haemoptysis and pneumonia, a left leg deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and gallstones.

During this time she had a number of routine cardiovascular investigations including outpatient CT scans, ECHOs and ECGs. She was seen at first 1 month after dissection repair then at 6 monthly intervals. During this time, ECHO demonstrated that the flow in the descending aorta was within normal limits but showed a mild area of flow turbulence in the aortic arch. There was mild aortic root and ascending aorta dilation but normal left ventricular cavity size and overall good left ventricular systolic function with evidence of mild–moderate aortic regurgitation but no aortic stenosis; the aortic valve cusps were slightly thickened but mobile.

Medical history

2005: Essential hypertension

2007: Postmenopausal osteoporosis with left humeral fracture (2003)

May 2009: Anaemia

August 2009: Pneumonia, peripheral neurogenic pain and reactive depression

December 2009: Lleofemoral DVT

March 2010: Haemorrhoids and gallstones

April 2010: Intercostal postherpetic neuralgia

Her current medication is as follows:

Bisoprolol 3.75 mg once daily

Lercanidipine 10 mg once daily

Fluoxetine 20 mg once daily

Losartan 100 mg once daily

Loperamide 2 mg as required (PRN)

Furosemide 40 mg once daily

Allergies: Rash with simvastatin, nausea with coamoxiclav

Family and social history

The patient is a retired practice nurse. She lives with her husband in a dormer bungalow with adaptations including a stair lift and bath chair. She is mobile and independent with a banana board and wheelchair and requires assistance from one healthcare professional with hygiene needs. She has an alcohol intake of ∼14 units/week and does not currently smoke; however, she does have a 40-pack-year history.

Her mother died of a ruptured aortic aneurysm and her father of a myocardial infarction.

Investigations

A 3D CT image series (figure 1) and 2D CT images (figure 2) were taken in February 2011 at her routine follow-up appointment 2 years postdissection.

Treatment

CT indicates significant dilation, of maximum diameter 78 mm, of the superior part of the ascending thoracic aorta, extending into the arch, suggestive of false-aneurysm formation at the surgical anastomoses. The patient therefore requires a further surgical procedure for resection of the aorta and reimplantation of the brachiocephalic vessels.

Concerning the morphology of the pathology CT suggests a pseudoaneurysm; however, it is possible that there is a secondary independent saccular aneurysm, the exact morphology will be determined during the surgical procedure.

Outcome and follow-up

At the time of publication further surgical intervention was being booked.

Discussion

The patient described in this case report developed secondary dilation of the aorta. A number of risk factors have been described for type A dissections including being woman, younger, having a dissection involving the supra-aortic branches, having a patent false lumen and having malperfusion syndrome.12

As mentioned, a residual patent false lumen influences the risk of postoperative aortic dilation; however, its long-term outcomes are not fully understood; one study demonstrated that the aortic dilation rate (calculated by aortic diameter comparisons) was greater for those patients with a patent false lumen but resulted in no significant difference in distal reoperation (at 10 years) or late survival13 with another group suggesting a patent false lumen of >70% of the total area of the diameter if the aorta is the strongest predictor of secondary dilation.14 Other studies have suggested that the presence of a partial thrombosis of the false lumen may be protective against dilation15 and there is evidence of the supportive role of antihypertensive therapy as reviewed by Zierer et al.16

The patient presented in this case report is a candidate for urgent reoperation on the aortic arch. Mohammadi et al17 analysed surgical approaches carried out on 29 similar patients who presented with false aneurysms of the ascending aorta after prosthetic replacement. They described one of the main problems of surgical therapy being safe re-entry into the chest as this is associated with a high risk of prosthetic rupture.

This case also indicates the need for radiological follow-up of dissection patients. There are no clearly defined guidelines regarding the frequency of radiological monitoring or the duration of follow-up. The most recent comprehensive study suggests that the follow-up intervals are dependent on postdissection aorta diameter; small aortas at 12-month intervals and larger aneurysms at 6 month or less intervals.16 They also investigated the onset of enlargement which varied from most occurring more than 1-year postdissection but some patients experiencing dilations after 10 years.16

In summary, there is a need for larger studies that may bring about clear guidelines and advise for multidisciplinary teams to better identify postdissection patients that are at risk of developing complications. Such studies may aid the development of complex care packages of radiological, medical and surgical interventions that are specific to each patient.

Learning points.

The presentation of a dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm is often asymptomatic or atypical (compared with dissections of the descending aorta) making accurate and rapid diagnosis problematic.

A dissecting aortic aneurysm should be considered as a differential diagnosis in the case of neurological findings especially in paraparesis that may indicate spinal artery pathology.

Postdissection patients require close follow-up and outpatient review with CT imaging even in the absence of cardiovascular symptoms. This allows early detection of any complications.

CT imaging provides gold-standard, accurate and potentially early identification of postaortic dissection complication.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Abraha I, Romagnoli C, Montedori A, et al. Thoracic stent graft versus surgery for thoracic aneurysm. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;1:CD006796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai ND, Pochettino A. Distal aortic remodelling using endovascular repair in acute DeBakey I aortic dissection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;21:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilienfeld DE, Gunderson PD, Sprafka JM, et al. Epidemiology of aortic aneurysms: I. Mortality trends in the United States, 1951–1981. Artheriosclerosis 1987;7:637–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pressler V, McNamara JJ. Aneurysm of the thoracic aorta. Review of 260 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985;89:50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bickerstaff LK, Pairolero PC, Hollier LH, et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysms: a population-based study. Surgery 1982;92:1103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson G, Markstrom U, Swedenborg J. Ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysms: a study of incidence and mortality rates. J Vasc Surg 1995:21:985–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasham SN, Guo DC, Milewicz DM. Genetic basis of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Curr Opin Cardiol 2002;17:677–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaul C, Dietrich W, Erbquth FJ. Neurological symptoms in aortic dissection: a challenge for neurologists. Cerebrovas Dis 2008;26:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song SW, Chang BC, Cho BK, et al. Effects of partial thrombosis on distal aorta after repair of acute DeBakey type I aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:841.e1–7.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pugliese P, Pessotto R, Santini F, et al. Risk of later reoperations in patients with acute type A aortic dissection: impact of a more radical surgical approach. Euro J Cardiothorac Surg 1998;13:576–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn LH. Cardiac surgery in the adult. Part V: diseases of the great vessels. 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Immer FF, Hagen U, Berdat PA, et al. Risk factors for secondary dilatation of the aorta after acute type A aortic dissection. Euro J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;27:654–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura N, Tanaka M, Kawahito K, et al. Influence of patent false lumen on long-term outcome after surgery for acute type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;136:1160–6, 1166.e1–3.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Immer FF, Krahenbuhl E, Hagen U, et al. Large area of the false lumen favors secondary dilatation of the aorta after acute type A aortic dissection. Circulation 2005;112(Suppl 9);I249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fattori R, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Bertaccini P, et al. Evolution of aortic dissection after surgical repair. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:868–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zierer A, Voeller RK, Hill KE, et al. Aortic enlargement and late reoperation after repair of acute type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi S, Bonnet N, Leprice P, et al. Reoperation for false aneurysm of the ascending aorta after UTS prosthetic replacement: surgical strategy. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]