Abstract

We report a case of Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis (HSVE) with a fatal outcome of a patient in his 70s presenting to a local teaching hospital with fever and confusion. We highlight pertinent issues regarding diagnosis, investigation and management, and consider ways of improving clinical outcomes. Finally, we discuss the differential diagnoses of acute encephalitis and review the management of HSVE.

Background

Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis (HSVE) is the most common cause of acute encephalitis1 and prognosis is grave if left untreated.2 Intravenous acyclovir greatly reduces mortality and morbidity if started early in the illness. Unfortunately delays in empirical treatment and definitive investigation by lumbar puncture (LP) continue to contribute to poor outcomes.1 3

We present a case of a patient in his 70s with fever and confusion, and discuss good management strategies and how such pitfalls may be avoided.

Case presentation

In our discussion, we refer to the time of symptom onset as day zero (0).

The patient presented with an abrupt onset of fever and acute confusion. He had seen general practitioners (GPs) on day 1 and 2 of illness but no cause was identified. Cefalexin was prescribed.

His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. He lived with his wife, and was independent of all activities of daily living. There was no known significant family history.

Examination revealed irregular tachycardia with variable pulse volume. Behaviour was abnormal with agitation, slow, hesitant speech and delayed responses to commands. There was no focal weakness or dysarthria. Fever was noted. Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) was 10/10.

Investigations

Initial blood tests were normal apart from mild neutrophilia (9.35×109/l), hyponatraemia (128 mmol/l) and mildly elevated C reactive peptide (5.3 mg/l). ECG confirmed atrial fibrillation.

Urgent head CT imaging was reported as showing ischaemic change at the right parieto-occipital region and an ‘old infarct’ in the right lentiform nucleus (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial head CT showing low attenuation in the right lentiform nucleus and medial temporal lobe.

Differential diagnosis

A patient in his 70s presents with fever and confusion. At this stage the differential diagnosis is vast. The details discussed so far, led us to a differential including urinary sepsis and encephalitis. Stroke was also considered in view of CT findings. We will discuss the results of further investigations that clinched the diagnosis, and the pitfalls encountered that led to a poor outcome in this case.

Treatment

Intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam (Tazocin) were started initially.

He failed to improve, and on day 4, intravenous acyclovir was started. By day 6 his conscious level progressively declined. Intravenmous ceftriaxone and amoxicillin were started and tazocin was stopped.

At this point, LP showed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis (28×106/l) and no organisms on Gram stain. CSF protein was elevated (0.82 g/l) and CSF glucose was 5 mmol/l; PCR was requested for common pathogens.

Owing to further drop in level of consciousness and risk of airway compromise, he was transferred to critical care, intubated and sedated. Generalised seizures were noted with leftward gaze deviation. Phenytoin and sodium valproate were initiated.

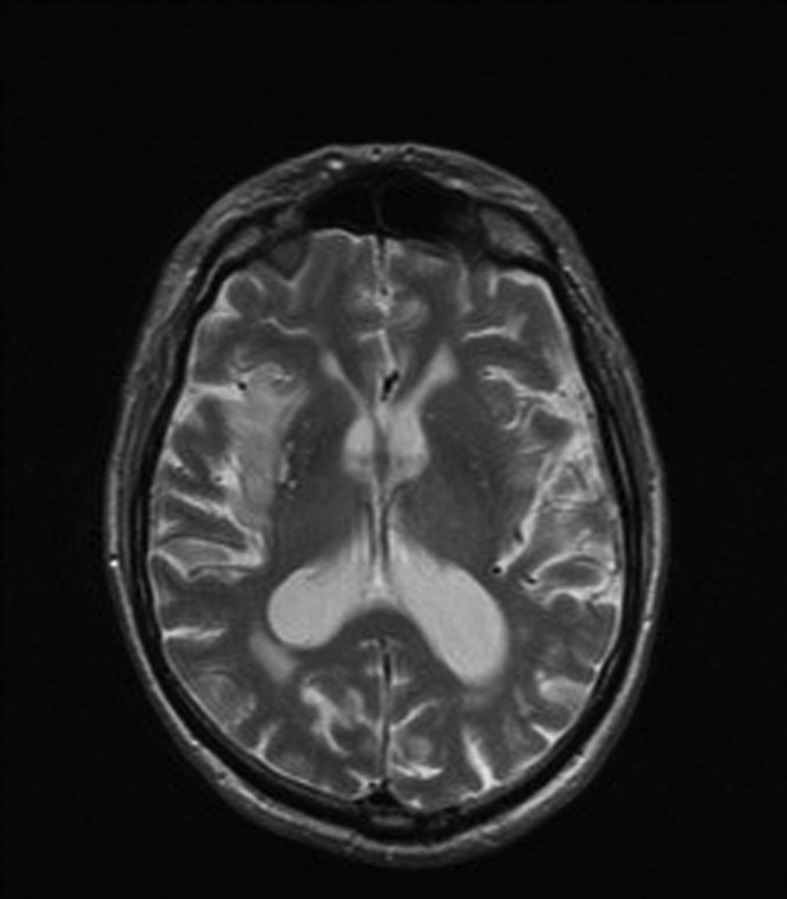

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on day 8 showed T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated-inversion-recovery (FLAIR) sequence hyperintensity in the right temporal lobe suggestive of HSVE (figure 2). EEG on day 10 showed focal right temporal periodic lateralising epileptiform discharges consistent with encephalitis or intracranial haemorrhage.

Figure 2.

T2-weighted MRI showing hyperintense signal in right medial temporal lobe structures.

HSV PCR results on day 15 were positive for HSV-1, confirming HSVE.

Outcome and follow-up

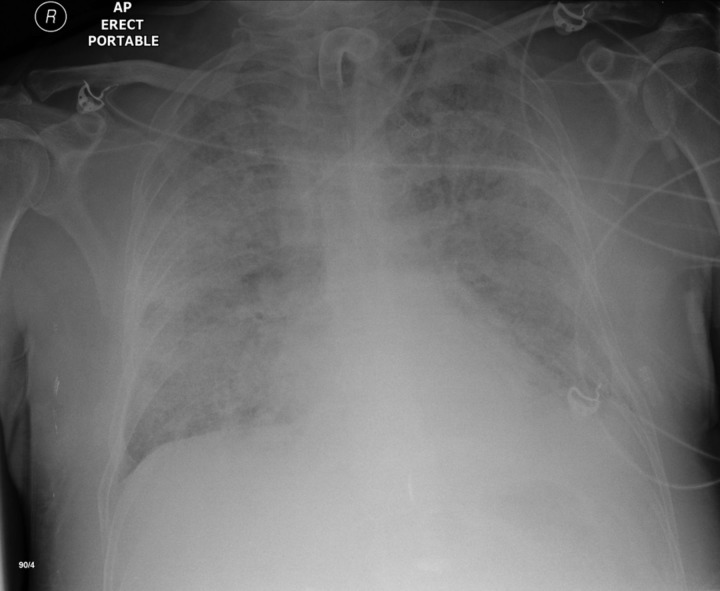

The patient never regained consciousness. Recovery was complicated by bilateral ventilator pneumonia and adult respiratory distress syndrome (figure 3). His poor neurological prognosis was noted. Treatment was withdrawn on day 29.

Figure 3.

Chest x-ray on day 27 of illness showing bilateral ventilator associated pneumonia.

Discussion

Acute confusion as a primary presenting complaint is extremely common.4 The challenge is in successfully teasing out the underlying cause. In patients presenting with fever and confusion, acute encephalitis should be considered early, especially when no other cause for febrile illness is identified.

Differentiating between the causes of acute encephalitis is essential to appropriate management and their key features are described in table 1. Guidelines by Association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association provide a comprehensive summary of the variety of causes of encephalitis and recommended management pathways.5

Table 1.

Important disorders causing CNS infection and common clinical features23–26

| Differentials | Clinical features |

|---|---|

| Viral | |

| Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) 1 and 2 | Fever |

| Hemicranial headache | |

| Language and behavioural abnormalities, memory impairment, seizures | |

| Brainstem syndrome | |

| SIADH | |

| Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) | Delirium |

| Vasculitis | |

| Delayed contralateral hemiplegia (ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve) | |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Evidence of widespread CMV disease for example retinitis, pneumonitis, adrenalitis, myelitis, polyradiculopathy |

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus, for example, West Nile Virus | Tick-borne-poliomyelitis like paralysis |

| Fever | |

| Headache | |

| Neck Stiffness | |

| Vomiting | |

| Human Herpesvirus 6 | Recent exanthema |

| Seizures | |

| Rhabdoviridae, eg, Rabies Virus | Agitation, hydrophobia, bizarre behaviour and delirium progression to disorientation, stupor, coma |

| Non-polio Enterovirus, eg, Echovirus/Coxsackievirus/Enterovirus 71 | Aseptic meningitis more common |

| Enterovirus 71 outbreak in children with rhombencephalitis: myoclonus, tremors, ataxia, cranial nerve defects | |

| Bacterial | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Rhomboencephalitis |

| Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) | Shortly after erythema migrans |

| Facial nerve palsy, radiculitis | |

| Fungal | |

| Crytococcus neoformans | Chronic meningitis |

| Immunogenic | |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) | Abrupt onset of neurological symptoms several days after viral illness or vaccination |

| Multifocal signs, eg, optic neuritis, ataxia, aphasia | |

| Disturbance of consciousness | |

| Bickerstaff's encephalitis | Progressive symmetrical external ophthalmoplegia and ataxia within 4 weeks of disease onset/hyperreflexia |

| Disturbance in the level of consciousness | |

| Acute haemorrhagic leukoencephalitis | Acute, rapidly progressive |

| Fever | |

| Seizures | |

| Focal neurological signs | |

| Coma | |

DFA, direct fluorescent antibody; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

Adult HSVE is an acute necrotising mesocortical and allocortical encephalitis affecting medial temporal and frontal lobe structures6 and results from HSV-1 reactivation. Around 60% of adults have serological evidence of previous HSV-1 infection,7 but the incidence of HSVE is only 2–4/million person-years8; causes for encephalitic reactivation are not known. The age specific incidence of HSVE is bimodal, with peaks in the young and the elderly.5 Recognising encephalitis in the elderly can be challenging, as they are at risk of a broader range of neurological disorders including stroke.5

Early studies showed that HSVE has a mortality exceeding 70% if untreated, reducing to 15–25% with acyclovir treatment.2 Early treatment predicts improved outcomes, and UK guidelines recommend treatment is started within 6 h of presentation.5

The majority of survivors have neuropsychiatric sequelae such as short-term memory problems, altered personality, dysphasia and epilepsy.

Pitfalls

We review principles of good management and pitfalls contributing to delayed management to highlight key lessons to be learnt.

Identify key features in the history

In HSVE, abrupt onset of fever, confusion and headache is classical. Altered behaviour, cognition, personality or consciousness may be noted.5 Often subtle details in change of behaviour or personality will be teased out from a good collateral history, which is a must in this scenario.5

Our patient did not complain of a headache but, he had altered behaviour and abnormal speech. Recognition of the salience of these findings could have guided diagnosis.

Look for clues in the examination

Common neurological findings include behavioural disturbance, altered cognition, evidence of prior seizures, and focal neurological deficit.5 Autonomic instability such as heart rate and blood pressure variability, and asystole10–12 has been described.

Focal neurological signs may not be apparent in early illness and are difficult to elicit in the agitated patient. Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) and AMTS are a poor discriminators of cognitive function and may be normal on presentation.5 The autonomic nervous system with major pathways arising from the insular cortex may be pathologically activated. Significant heart rate variability and dysrhythmia in the absence of structural cardiac abnormality (echocardiography was normal) in our patient suggests central autonomic nervous system dysfunction.

Priorities in investigation

Blood investigation findings are typically non-specific13 but help in excluding systemic inflammation and sepsis.

All patients with suspected HSVE should have a LP as soon as possible, unless there is clinical contraindication.5 Clinical contraindications include evidence of obstructive raised intracranial pressure, moderate to severe impairment of consciousness (GCS<13), fall in GCS>2, focal neurological signs, abnormal posturing, papilloedema and immunocompromise.5 In such cases, an urgent CT head scan should be performed first.

In our case, there was no clinical contraindication to performing LP first. The erroneous use of CT head to guide LP decision making is potentially hazardous, as such tests introduce avoidable delay in diagnosis and non-specific findings may distract from focused management, as in this case.

MRI has greater sensitivity14 15 and should be performed in preference on all patients with suspected encephalitis for whom the diagnosis is uncertain, and ideally should be within 24 h of hospital admission.5 13 Hyperintense signal on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences in the cingulate gyrus and medial temporal lobes is suggestive of HSVE. In our case, head MRI was the first radiological modality of investigation to suggest a specific aetiological diagnosis but occurred on day 8, 6 days after CT.

Typical CSF findings with HSVE include moderately elevated CSF opening pressure, moderate CSF pleocytosis, mildly raised CSF protein and normal CSF:plasma glucose ratio. Note in our case, plasma glucose was not obtained at the same time as CSF glucose, which leads to increased difficulty in interpretation of CSF results.5 CSF PCR test for HSV (1 and 2) is the gold standard diagnostic test. Paired CSF and serum serology is also recommended, in case of PCR negative but serology-positive disease.16

An EEG plays an adjunctive role in diagnosis. For patients with mildly altered behaviour and uncertainty whether there is a psychiatric or organic cause, an EEG should be performed to seek encephalopathic changes.5 Non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) can mimic acute encephalitis, and rapid access to EEG to confirm NCSE and to treat specifically is important5

Treat empirically

Treatment should be started on the basis of clinical suspicion as poor outcomes are associated with delay. UK National Guidelines recommend that treatment should be started within 6 h of admission if suspected, when the results of initial CSF and/or imaging may not be available.5

Acyclovir is the first line treatment for HSVE. The evidence for this was established in two major randomised control trials.17 18 UK National Guidelines recommend using 10 mg/kg 8 hourly for 14–21 days, and a repeat LP should be performed at this time to confirm CSF is negative for HSV by PCR.5 Resistance to acyclovir is uncommon and is mostly seen in the immunodeficient.19 20 Evidence is lacking for second line treatment in this context, but reports suggest foscarnet21 and cidofovir are effective.19

Corticosteroids may play a role in managing cerebral oedema as a complication of HSVE. There is currently limited evidence to suggest benefit in uncomplicated cases. Outcomes of The German trial of Acyclovir and Corticosteroid in Herpes simplex Encephalitis are awaited.22

Conclusion

HSVE remains clinically important, but unfortunately continues to be suboptimally managed. The UK National Guidelines on the Management of Patients with Encephalitis will improve clinical awareness of diagnostic and treatment strategies.5

Learning points.

To be aware of Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis (HSVE) as a key differential in a vague presentation of fever and confusion, particularly in the elderly.

Features not to be missed in assessing a patient with HSVE include behavioural disturbance, changes in personality, cognition and autonomic instability.

Diagnosis of HSVE is clinched by lumbar puncture, followed by cerebrospinal fluid PCR.

If suspected, HSVE must be treated empirically within 6 h of admission.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Michael BD, Sidhu M, Stoeter D, et al. Acute central nervous system infections in adults—a retrospective cohort study in the NHS North West region. QJM 2010;103:749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitley R, Soong S, Dolin R, et al. Adenine arabinoside therapy of biopsy-proved herpes simplex encephalitis. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases collaborative antiviral study. N Engl J Med 1977;297:289–94.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell DJ, Suckling R, Rothburn MM, et al. Management of suspected herpes simplex virus encephalitis in adults in a UK Teaching Hospital. Clin Med 2009;9:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcantonio E. In the clinic. Delirium. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:ITC6-1, ITC6-2, ITC6-3, ITC6-4, ITC6-5, ITC6-6, ITC6-7, ITC6-8, ITC6-9, ITC6-10, ITC6-11, ITC6-12, ITC6-13, ITC6-14, ITC6-15; quiz ITC6-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon T, Michael B, Smith P, et al. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in adults—Association of British Neurologisys and British Infection Association National Guidelines. J Infect, 2012;64:347–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damasio AR, van Hoesen GW. The limbic system and localisation of herpes simplex encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA 2006;296:964–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conrady CD, Drevets DA, Carr DJJ. Herpes Simplex Type I (HSV-1) Infection of the Nervous System: is an Immune Response a Good Thing? J Neuroimmunol 2010;220:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon T, Hart IJ, Beeching NJ. Viral Encephalitis: a clinician's guide. Pract Neurol 2007;7:288–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gooch R. Ictal asystole secondary to suspected herpes simplex encephalitis: a case report. Cases J 2009;2:9378–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith BK, Cook MJ, Prior DL. Sinus node arrest secondary to HSV encephalitis. J Clin Neurosci 2008;15:1053–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsolaiman MM, Alsolaiman F, Bassas S, et al. Viral encephalitis associated with reversible asystole due to sinoatrial arrest. South Med J 2001;94:540–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner I, Budka H, Chauduri A, et al. Viral meningoencephalitis: a review of diagnostic methods and guidelines for management. Eur J Neurol 2012;17:999–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroth G, Gawehn J, Thron A, et al. Early diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by MRI. Neurology 1987;37:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Provenzale JM. CT and MR imaging in nontraumatic neurologic emergencies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:288–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denes E, Labach C, Durox H, et al. Intrathecal synthesis of specific antibodies as a marker of herpes simplex encephalitis in patients with negative PCR. Eur J Med Sci 2010;140:13107–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skoldenberg B, Forsgren M, Alestig K, et al. Acyclovir versus vidarabine in herpes simplex encephalitis. Randomised multicentre study in consecutive Swedish patients. Lancet 1984;2:707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitley RJ, Alford CA, Hirsch MS, et al. Vidarabine versus acyclovir therapy in herpes simplex encephalitis. N Engl J Med 1986;314:144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlich KS, Mills J, Chatis P, et al. Acyclovir-resistant Herpes-Simplex Virus-infections in patients with the acquire immunodeficiency syndrome. NEngl J Med 1989;320:293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimberlin DW. Management of HSV encephalitis in adults and neonates: diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Herpes 2007;14:11–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulte EC, Sauerbrei A, Hoffmann D, et al. Acyclovir resistance in herpes simplex encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2010;67:830–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francisco M-T, Menon S, Pritsch M, et al. Protocol for German trial of Acyclovir and corticosteroids in Herpes-simplex-virus-encephalitis (GACHE): a multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled German, Austrian and Dutch trial (ISRCTN45122933). BMC Neurol 2008;8:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC, et al. The Management of Encephalitis: Clinical practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:303–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone MJ, Hawkins CP. A medical overview of encephalitis. Neuropsychol Rehabil Int J 2007;17:429–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granerod J, Cunningham R, Zuckerman M. Causality in acute encephalitis: defining aetiologies. Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:783–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonneville R, Klein IF, Wolff M. Update on investigation and management of postinfectious encephalitis. Cur Opin Neurol 2010;23:300–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]