Abstract

Acute compartment syndrome affecting the gluteal region is rare when compared to the same condition in the forearm or calf. When it does occur, it is usually due to prolonged immobilisation in those with altered consciousness. Gluteal compartment syndrome resulting from injury to the superior gluteal artery is extremely rare and to our knowledge has been described only twice—both after high-energy road traffic accidents (RTA). Other cases have described profound hypotension with superior gluteal artery injury after an RTA and falling off a horse, without acute gluteal compartment syndrome. We present a case of gluteal compartment syndrome due to rupture of the superior gluteal artery following a relatively minor fall. The patient required an emergency fasciotomy, which was performed within 4 h of the injury. This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of this rare condition.

Background

This is a rare presentation of gluteal compartment syndrome, which demonstrates significant arterial injury with no hypotensive changes after a low energy injury. The case shows how important it is to diagnose compartment syndrome quickly and the morbidity that can occur if not treated. This case further discusses the management of gluteal compartment syndrome in the context of superior gluteal artery rupture and compares treatment options with similar published cases.1–4

Case presentation

A 61-year-old male lorry driver fell backwards from his vehicle onto concrete. He fell approximately 1 m, landing on his right buttock. He was unable to bear weight due to pain but was able to mobilise on his hands and knees and summon help from a passerby within 30 min. He had not sustained any other injuries and was conscious throughout. Paramedics managed to move the patient onto a stretcher lying on his left side; however, the patient's pain in his right buttock and hip was deteriorating, not responding to an intravenous dose of morphine (10 mg).

He was admitted to the emergency department at the James Paget University Hospital where he was assessed according to Advanced Trauma and Life Support guidelines. He was haemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 128/100 mm Hg and pulse rate of 81 beats/min. His haemoglobin levels were 14.4 g/dl. His pain was localised to his right buttock and did not respond to a further 10 mg of intravenous morphine and 30 mg Levobupivacaine Fascia Iliaca Block. X-ray investigation revealed no fracture of his pelvis or hip and he was referred to the on-call orthopaedic team. On assessment 1 h after his admission, he had hard, tense, non-pulsatile mass which measured 30 cm×20 cm in his right gluteal region with no overlying skin compromise (figure 1). By this stage, he was only able to lie prone on the trolley due to pain. He had no neurological deficit and his pain was deteriorating. Senior orthopaedic review (HD) was sought within 10 min of referral. A diagnosis of acute gluteal compartment syndrome was made clinically and he was prepared for theatre.

Figure 1.

A 30 cm×20 cm right gluteal mass with no overlying skin compromise 1-h post injury. Arrow indicating mass protrusion.

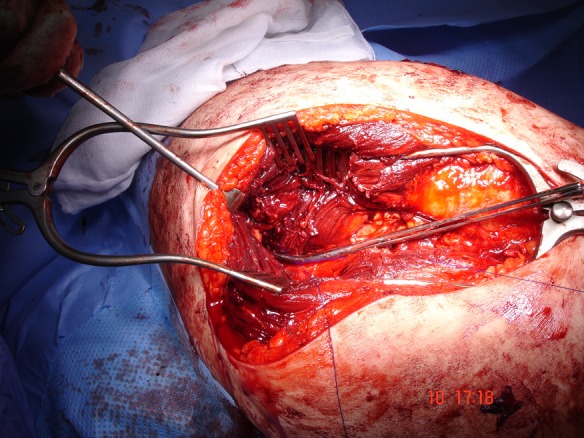

The time from injury to theatre was 4 h. Induction of general anaesthesia was difficult, as it had to be performed in a semi-prone position due to his continued pain. A cuffed, endotracheal tube was inserted and the patient was positioned in the left lateral position. An extended posterior approach to the hip was used for the decompression. The muscle under the fascia lata was dark purple in colour and under immense pressure. A large amount of blood clot was removed from within the gluteus maximus, under the gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata. Dead muscle from the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata was removed. After debridement, arterial blood was seen to be trickling from the proximal part of the dissection. This was tracked proximally through the gluteus maximus where a branch of the superior gluteal artery was identified and found to be transected. The area of the vessel, which was bleeding heavily, was about 1 cm2 suggesting that the injury to the vessel was quite proximal (figure 2). With the help of a senior surgical colleague (VC), the vascular pedicle was tied and packed with Surgicel. The patient required 2 litre of crystalloid intraoperatively and 1 unit of packed red cells after the tamponading effect of the clot was removed. Metraminol was used additionally to maintain blood pressure. The skin edges were approximated by a boot-lace technique and a non-vacuum drain left in situ.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative picture depicting postcompartment release and debridement with arterial control.

On the first postoperative day, the patient was lying in bed comfortably with minimal analgesic requirements and no neurovascular compromise. He was very grateful for the prompt intervention as ‘it was the worst pain I'd ever had’. Two days later, a further wound debridement was performed to remove further dead muscle. Four days after the initial surgery, final closure of the wound was achieved. Prophylactic antibiotics were given intravenous postoperatively until the wound had been closed.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient left the hospital partially weight bearing with crutches 7 days after his injury. At his last review (3-month post injury), he is functionally back to normal with no limp and has returned to work.

Discussion

Compartment syndrome arises from microvascular compromise due to increased pressure within a closed, osseo-fascial compartment resulting in tissue ischemia5 causing cellular hypoxia and death. The increased pressure can be external (tight cast) or internal (tissue oedema/haemorrhage) or a combination. As with all compartment syndrome, gluteal compartment syndrome presents with severe pain that is resistant to analgesia, tense swelling and pain exacerbation on passive stretch or pressure. Neurological deficit is a late sign and occurs due to pressure on the sciatic nerve.

The gluteal region is one of the rarest parts of the body to be affected by compartment syndrome. Gluteal compartment syndrome is most commonly associated with prolonged immobilisation (peroperatively6 after drug overdose7 or alcohol intoxication) and obesity.5 Other causes include trauma,1–3 as a complication of joint replacement surgery8 intramuscular drug abuse9 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome10 and infection.11

There are three distinct gluteal compartments: gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and minimus, and tensor fascia latae.12 13 The release of all these compartments is vital in the treatment of compartment syndrome in the gluteal region. Studies have shown that ischaemia of 4 h duration can cause irretrievable muscle damage.12 14 This case shows that permanent muscle ischaemia (ie, muscle death) can occur before this allotted timeline and this in our case, was due to the high tamponading pressures caused by the arterial bleed. This highlights that early diagnosis is key to reducing morbidity. Compartment pressure monitoring can aid in diagnosis especially in obtunded patients. One study suggests that a normal gluteal compartment pressure is 13–14 mm Hg14 and pressures greater than 30 mm Hg an indicator for fasciotomy.13 As in this case, if clinical suspicion of compartment syndrome is high then fasciotomies should be performed.13 Untreated compartment syndrome has serious implications resulting in muscle and nerve necrosis, systemic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis with myoglobinuria and subsequent renal failure and possibly death.15

Superior gluteal artery rupture due to blunt trauma is rare and, to our knowledge, is only the third case to describe this presentation with superadded compartment syndrome. What makes this case unique is the lack of haemodynamic change associated with haemorrhage, the short-time frame in which muscle ischaemia occurred and the relatively low energy of the injury.

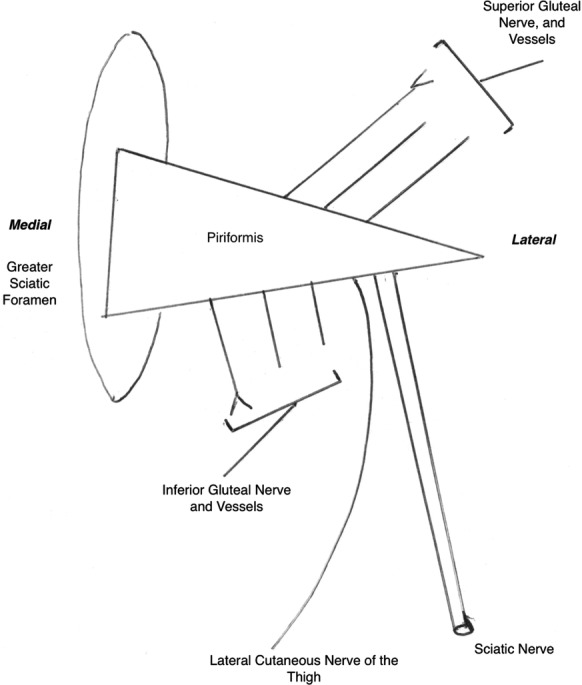

The superior gluteal artery arises from the internal iliac artery deep in the pelvis exiting through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the gluteus medius and superior to the piriformis muscle (figure 3). The superior gluteal artery mainly supplies the gluteus medius and minimus and divides into the deep and superficial branches, which supplies gluteus maximus. The deep branch further divides into superior and inferior divisions; with the superior division running superior to the gluteus minimus and anastomosing with lateral femoral and iliac circumflex arteries, and the inferior division running oblique across the gluteus minimus anastomosing with the lateral femoral circumflex artery. It is difficult to know exactly which branch of the vessel had been transected without the aid of an angiogram. The cross-sectional area of the vessel was approximately 1 cm2 and might possibly have been the inferior division of the deep-branch of the superior gluteal artery. Rupture of the superior gluteal artery is frequently associated with unstable pelvic fracture and penetrating injuries,1–4 but has also been shown with hip dislocation2 and stable pelvic fractures.16 17 The anatomical predilection to superior gluteal artery injury is the structure's proximity to the sciatic notch. Shearing forces through this area during the mechanism of injury are thought to rupture this vessel. It is also at risk from fracture of the acetabulum and displacement from an unstable hemipelvis.1–4 16 17

Figure 3.

Diagram to demonstrate the anatomy and relationship of the superior gluteal neurovascular complex in the gluteal region.

Our case differs from the previous cases of superior gluteal artery rupture described.1–4 The patient had no signs of haemodynamic instability and clinically presented as gluteal compartment syndrome. The other cases are characterised by hypotensive changes. In these cases, it is suggested that active bleeding should be accompanied by angiography1 3 4 even in the presence of compartment syndrome1 due to risk of profuse bleeding, poor visualisation and risk to the sciatic nerve. However, where surgical embolisation fails surgical intervention is required.3 In Brumback1 fasciotomy was delayed due to haemodynamic instability allowing embolisation of the superior gluteal artery before fasciotomy was performed 7.5 h after the initial injury and required no muscle debridement. In our case, the presence of no haemodynamic instability may suggest the compartment pressure was significantly higher than the Brumback1 case. This case shows a picture of rapid ischaemia and muscle death within a 4 h period requiring earlier intervention with fasciotomy. The history of a low energy injury with no sign of active bleeding earmarks this as an alternative presentation of superior gluteal artery rupture with concomitant compartment syndrome without haemodynamic instability as an indicator for angiography.

Taylor et al2 describes a gluteal compartment syndrome with superior gluteal artery rupture post traumatic hip dislocation after a road traffic accident. This patient developed their compartment syndrome the day after the initial injury but showed no sign of haemodynamic instability. This required surgical exposure with fasciotomy and likewise the source of the bleeding was identified as the superior gluteal artery trunk, which required ligation. Muscle debridement of the piriformis and gluteus maximus was required. These ischaemic changes had occurred within the four and half hours from presentation of their gluteal compartment syndrome.

This case raises the debate between radiological intervention prior to surgical exposure. Angiography in the presence of haemodynamic instability is the method of choice prior to treatment of gluteal compartment syndrome. However, in the presence of haemodynamic stability and gluteal compartment syndrome, surgical delay in fasciotomy is ill advised due to the morbidity of muscle necrosis, sciatic nerve damage, rhabdomyolysis and renal failure that can occur if left untreated. This is emphasised more by the short timeline of less than 4 h in which this can occur. It is recommended that vascular surgeons or radiological intervention, if available on site; is ready if vascular complications such as uncontrolled superior gluteal artery haemorrhage or retraction should arise.1 2

Learning points.

It is important to diagnose compartment syndrome early to reduce morbidity and mortality to the patient.

Angiography is the investigation of choice in haemodynamically unstable patients prior to compartment release.

In the presence of haemodynamic stability surgical delay in fasciotomy is not recommended.

Vascular surgery or interventional radiology facilities are recommended to be available on site if any vascular complications should arise.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Brumback RJ. Traumatic rupture of the superior gluteal artery, without fracture of the pelvis, causing compartment syndrome of the buttock. J Bone Joint Surg 1990;72:134–7.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor BC, Dimitris C, Tancevski A, et al. Gluteal compartment syndrome and superior guteal artery injury as a result of simple hip dislocation. Iowa Orthop J 2011;31:181–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belley G, Gallix BP, Derossis AM, et al. Profound hypotension in blunt trauma associated with superior gluteal artery rupture without pelvic fracture. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care 1997;43:703–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kligman M, Mahrer Avi E, et al. Hypotension as a delayed complication of rupture of a branch of the superior gluteal artery, following buttock contusion. Injury Int J Care Injured 2002;33:285–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar V, Saeed K. Gluteal compartment syndrome following arthroplasty under epidural anaesthesia: a report of 4 cases. J Orthop Surg 2007;15:113–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyn J, Ladurner R, Ozimek AT, et al. Gluteal compartment syndrome after prostatectomy caused by incorrect positioning. Eur J Med Res 2006;11:170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torrens C, Marin M, Mestre C, et al. Compartment syndrome and drug abuse. Acta Orthop Belg 1993;59:143–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pai VS. Compartment syndrome of the buttock following a total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1996;11:609–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.klockgether T, Weller M, Haarmeier T, et al. Gluteal compartment syndrome due to rhabdomyolysis after heroin abuse. Neurology 1997;48:275–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmalzried TP, Eckardt JJ. Spontaneous gluteal artery rupture resulting in compartment syndrome and sciatic neuropathy: report of a case in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Clin Orthop 1992;275:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kontrobarsky Y, Love J. Gluteal compartment syndrome following epidural analgesic infusion with motor blockage. Anaesth Intensive Care 1997;25:696–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa N, Hyun A, Kumar JS, et al. Gluteal compartment syndrome: a case report. BioMed Central Cases J 2009;2:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keene R, Froelich JM, Milbrandt JC, et al. Bilateral guteal compartment syndrome following robotic-assisted prostatectomy. Orthosupersite 2010;33:852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteside TE, Hirada H. The response of skeletal muscle to temporary ischaemia: an experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1971;53:1027–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida H. Gluteal Compartment syndrome. A report of 4 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1992;63:347–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haikel S, Willett K. Traumatic rupture of the superior gluteal artery with a stable fracture. Injury Int J Care Injured 2000;31:383–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M, Haene RA. Superior gluteal artery rupture associated with an isolated fracture of the sacrum Injury, Int. J Care Injured 2011;42:719–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]