Abstract

The authors report a case of a 6-week-old baby girl who was admitted to the paediatric ward due to a high fever for 2 days. The patient experienced three fits which took place while in the ward. A brain sonogram showed subdural heterogeneous collection consistent with focal empyema; however, no hydrocephalus or infarction was detected. An urgent Burr hole procedure was performed to remove the collected pus. Both blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture grew Salmonella species which remain sensitive to some antibiotics. This strain was sent to the institute of medical research (IMR) for serotyping. The patient was treated with intravenous combination of ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin for 3 weeks. One week later, IMR sent results that identified the strain as Salmonella enterica serotype Houtenae. Following antibiotic treatment, repeat ultrasound illustrated an improvement of the subdural empyema, and the gram stain of the CSF specimen failed to isolate bacteria.

Background

Clinicians should be alerted on the existence and progression of different pathogens which can cause meningitis. This should be done in order to implement early control measures. These control measures can then be applied to prevent any further complications. Even after an apparently satisfactory clinical response to antibiotics; staff and parents should be aware that there is still an ongoing need to remain vigilante due to the possibility of relapse.

Case presentation

A 6-week-old Indonesian girl was admitted to the Paediatric Emergency Department of Kuala Lumpur General Hospital with symptoms of poor feeding, grunting respiration, weight loss and fever which had gone on for 2 days. She was born at term, by spontaneous vaginal delivery with a birth weight of 1.8 kg without antenatal, intranatal or postnatal complications. The patient stayed at the paediatric ward 3 days postdelivery due to low birthweight and then discharged having been immunised with the BCG and first dose hepatitis B. However, 2 days prior to admission, her grandmother noticed that the baby was feeding poorly and had a raised body temperature. There was no history of diarrhoea, vomiting, altered consciousness, or convulsion. According to her grandmother, the child’s mother who was Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) positive suffered puerperal psychosis and either died or committed suicide at home few days after delivery.

On examination, the patient was febrile (3.9.1°C), her respiratory rate was 30/min with shallow respiration and heart rate of 160 beats/min. The patient was lethargic, but no pallor, cyanosis, clubbing, icterus or lymphadenopathy was detected. Examination of the skull revealed normal (non-bulging) anterior fontanelle. The rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

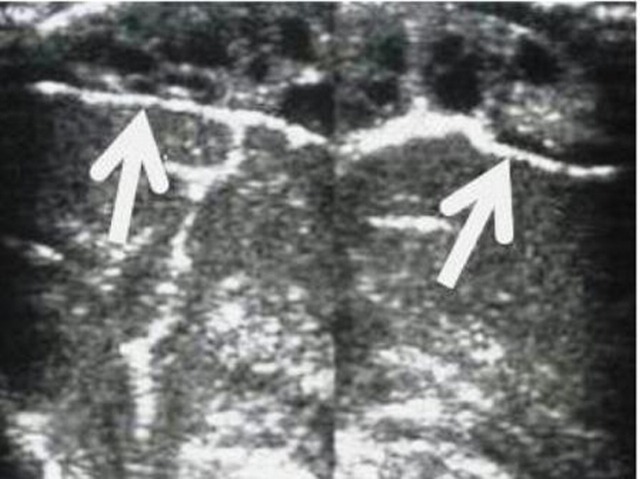

While in the ward the child had three episodes of fits and urgent brain ultrasound was performed to show subdural heterogeneous collection consistent with focal empyema, but no evidence of hydrocephalus or infarction were detected (figure 1). Urgent burr-hole procedure was performed to remove the collected pus.

Figure 1.

Sonogram at 6 weeks of age shows a complex heterogeneous collection consistent with focal empyema.

A diagnosis of neonatal sepsis was made, and she was administered empirically with intravenous benzylpenicillin and gentamicin. The C reactive protein was high, the initial peripheral white cell count was within the normal range (differential count showed 83% neutrophils, 15% lymphocytes and 2% eosinophils), elevated platelet count and a low haemoglobin level (table 1). Serum and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) VDRL tests were negative.

Table 1.

Laboratory investigations result

| Test | Results | Units | Range |

| Full blood count | |||

| White cell count | 16 | ×109 cells/l | 5–21 |

| Haemoglobin | 10.3 | g/dl | 15.2–19.8 |

| Platelet count | 598 | ×109 cells/l | 150–400 |

| C reactive protein | 2.3 | mg/l | 0.0–0.5 |

| Renal profile | |||

| Sodium | 138 | mmol/l | 135–150 |

| Potassium | 3.7 | mmol/l | 3.5–5.0 |

| Urea | 4.4 | mmol/l | 2.5–6.4 |

| Creatinine | 79 | µmol/l | 62–106 |

| Liver function test | |||

| Albumin | 43 | g/l | 35–50 |

| Total protein | 83 | g/l | 67–88 |

| Bilirubin total | 21 | µmol/l | <23 |

| ALT | 23 | U/l | <44 |

| ALP | 73 | U/l | 32–104 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | |||

| Appearance | Cloudy | Clear | |

| WCC | 3.07 | ×109 cells/l | 0.7 |

| Lymphocytes | <60% | ×109 cells/l | 80–90% |

| Glucose | Undetectable | mg/dl | 40–80 |

| Protein | 533 | mg/dl | 4–40 |

| RBC | 0.680 | ×109 cells/l | Nil |

ALP, Alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; RBC, red blood cell; WCC, white cell count.

Lumbar puncture revealed a cloudy-bloodstained CSF and Gram-negative rods were observed under Gram’s stain (table 1).

Treatment

Blood culture and CSF grew Salmonella species which remained sensitive to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, ceftriaxone and co-trimoxazole. Stool culture was negative. The strain was sent to IMR for serotyping. On the basis of blood and CSF culture results, the patient was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone 75 mg/kg/day as a single injection and intravenous ciprofloxacin infusion 30 mg/kg/day, this medication regimen was given for 21 days. One week later, serotyping results revealed S enterica serotype Houtenae.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient completed the antibiotics medication regimen and repeat ultrasound illustrated marked improvement of the subdural empyema. Another CSF analyses performed before discharge revealed a clear CSF. The white cell count in the CSF decreased to 0.079×109 cells/l, with 87% lymphocytes. The protein and glucose levels were 275 mg/dl and 33 mg/dl, respectively. The gram stain of that CSF specimen failed to reveal bacteria. She has been scheduled for follow-up visits to monitor her milestone and neurodevelopment assessment.

Discussion

A case control study showed that breast-feeding decreases the risk of sporadic salmonellosis in infants.1 On the other hand, S enterica serotype Kottbus, was initially thought to have a specific predilection for colonising within human mammary glands.2 In the following years, several reports showed that other serotypes, including S enterica serotype Typhimurium,3 Salmonella enterica serotype Senftenberg,4 S enterica serotype Typhimurium definite type 104 (DT104),5 and S enterica serotype Panama6 can also be transmitted via breast milk. Our report extended the list of salmonellae that might be transmitted via this vesicle. There is, in existence, a strange phenomena which suggests that there might be a relationship between keeping reptiles as pets and Salmonella meningitis in children, two fatal cases have been reported in UK.7

S meningitis is uncommon in developed countries; however, it is quite common in the form of gram-negative bacterial meningitis in Africa, Brazil and Thailand.8 Non-typhoid Salmonella is the commonest cause of bacterial gastroenteritis among children in urban areas of Malaysia.9

The first human report of bacteraemia due to S enterica serotype Houtenae in Brazil was observed in a HIV-infected patient. Between 1996 and 2000, less than 1% of 4581 Salmonella strains were isolated from non-human sources belonged to S enterica serotype Houtenae.10

Between 1973 and 1997, Department of Paediatrics at the University of Malaya Medical Centre in Kuala Lumpur conducted a study of bacterial meningitis along with the complications it produced in infants. In the past Salmonella has not been a common aetiological agent of bacterial meningitis in urban Malaysia in comparison to Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumonia.9 However, researchers have managed to isolate 13 (approximately 5%) Salmonella species from samples of CSF. All patients were infants below 1 year of age and fever was the main presenting symptom in all cases. Other presenting features included; subdural effusion (four cases), hydrocephalus (five cases), empyema (three cases), ventriculitis (two cases) and one case developed a cerebral abscess.

Learning points.

-

▶

Meningitis can be caused by pathogens that are primarily infecting the gastrointestinal tract.

-

▶

Meningitis in infants can lead to serious sequelae, so early detection and proper treatment is mandatory.

-

▶

The Possibility of relapse after apparent recovery should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the director of Hospital Kuala Lumpur for his permission to publish this case.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Rowe SY, Rocourt JR, Shiferaw B, et al. Breast-feeding decreases the risk of sporadic salmonellosis among infants in FoodNet sites. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38(Suppl 3):S262–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryder RW, Crosby-Ritchie A, McDonough B, et al. Human milk contaminated with Salmonella Kottbus: a cause of nosocomial illness in infants. JAMA 1977;238:1533–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drhová A, Dobiásová V, Stefkovicová M. Mother’s milk–unusual factor of infection transmission in a salmonellosis epidemic on a newborn ward. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol 1990;34:353–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revathi G, Mahajan R, Faridi MM, et al. Transmission of lethal Salmonella senftenberg from mother’s breast-milk to her baby. Ann Trop Paediatr 1995;15:159–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qutaishat SS, Stemper ME, Spencer SK, et al. Transmission of Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 to infants through mother’s breast milk. Pediatrics 2003;111:1442–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Te-Li C, Peck-Foong T, Shu-Chin L, Chang-Phone F, Siu LK. First report of Salmonella enterica Serotype Panama meningitis associated with consumption of contaminated breast milk by a neonate. J Clinic Microb 2005;43:5400–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. Baby dies of Salmonella Poona infection linked to pet reptiles. Communicable Disease Report CDR Weekly Report 2000;10:161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan JP, Da Silv HR, Taveres A, et al. Etiology of and mortality from bacterial meningitis in northastern Brazil. Rev Infect Dis 1990;12:128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee WS, Puthucheary SD, Omar A. Salmonella meningitis and its complications in infants. J Paediatr Child Health 1999;35:379–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavechio AT, Ghilardi AC, Peresi JT, et al. Salmonella serotypes isolated from nonhuman sources in São Paulo, Brazil, from 1996 through 2000. J Food Prot 2002;65:1041–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]