Abstract

A 22-year-old second gravida presented with asymptomatic abdominal and pelvic hydatid disease at 16 weeks gestation. She opted for conservative management and was treated with oral Albendazole. She underwent elective caesarean along with cyst excision at term as the large pelvic cyst precluded vaginal delivery. A healthy baby girl weighing 2600 g with Apgar of 9, 9 at 1 and 5 min was delivered.

Background

Hydatid disease caused by Echinococcus granulosus is common in tropical countries but it is rare in pregnancy with a reported incidence of 1 in 20 000 to 1 in 30 000.1–3 The presentation may range from asymptomatic disease to acute complications like cyst rupture, anaphylaxis and obstruction of labour.1 2 4 Since the condition is rarely encountered in pregnancy, there are no standard guidelines available for its treatment.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old second gravida presented to the antenatal clinic at 16 weeks of gestation for a routine antenatal visit. She had no significant medical or surgical history. On abdominal examination gravid uterus of 16-week size appeared to be pushed anterolaterally to the right by a separate non-mobile mass arising from the pelvis. On vaginal examination the same cystic mass was felt posterior to uterus as a bulge in the posterior fornix. Rectal examination confirmed the mass to be anterior to rectum.

Investigations

An ultrasound revealed a single live fetus corresponding to gestation. There was a large cystic lesion in the pelvis pushing the uterus anterolaterally. MRI confirmed multiple well-encapsulated multicystic lesions with internal daughter cysts and matrices suggestive of hydatid cysts. The largest cyst was midline in the pelvis (18×15×10 cm). Another cyst was found in right subphrenic region (16×14×8 cm) and two in right lumbar region (8×8×5 cm and 5×6 cm). Indirect haemagglutination test was positive for cystic echinococcosis. The patient's haemogram, blood sugar, liver and kidney function tests were normal.

Treatment

Management options including surgical removal of the cysts in second trimester, medical management vis-á-vis expectant management were discussed with the patient. The patient declined surgery and opted for medical management. Physician opinion was taken and the patient was put on tablet Albendazole 400 mg daily for 6 weeks. However it required discontinuation after 4 weeks due to neutropenia. Neutropenia resolved spontaneously on discontinuation and albendazole was restarted after 2 weeks for another 6 weeks’ duration. During this period she received routine antenatal care. Her leukocyte counts and biochemical profile remained normal throughout. The fetus showed normal growth and she did not develop any obstetric complications.

Outcome and follow-up

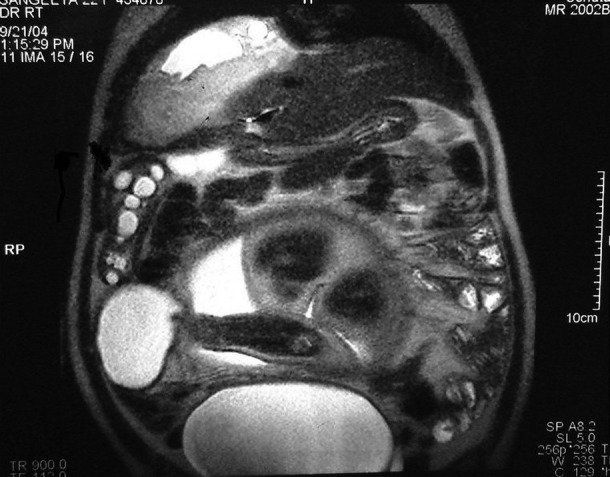

Near term the patient was reassessed to decide the mode of delivery. Abdominal examination indicated longitudinal lie with free-floating fetal head. Bimanual examination revealed whole of pelvis occupied by cystic mass which was preventing descent of fetal head. Repeat MRI (figure 1) was done to assess the response of the hydatid cysts to medical therapy and to plan excision of resectable cysts. MRI revealed disappearance of one of the two cysts located anterior to kidney and calcification of the subphrenic cyst. The pelvic cyst showed a marginal decrease in size. The findings were discussed with the patient and an elective lower segment cesarian section (LSCS) along with excision of hydatid cysts was planned in consultation with surgical team at 38 weeks gestation.

Figure 1.

MRI showing multiple abdominal and pelvic hydatid cysts.

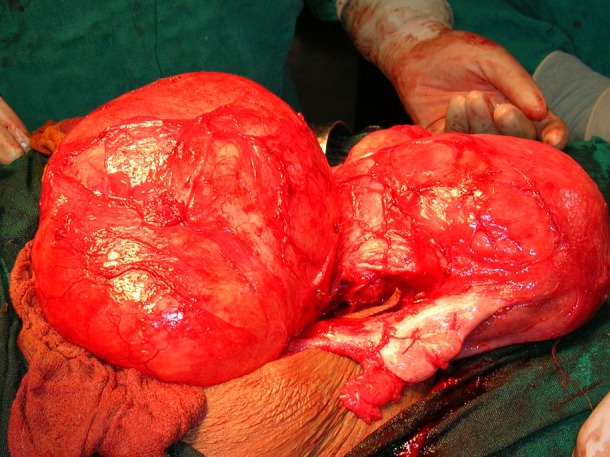

A healthy female baby weighing 2600 g with an Apgar of 9, 9 at 1 and 5 min was delivered by elective LSCS at 38 weeks as planned. The uterine incision was closed in double layer as per routine and the uterus was exteriorised to improve visibility and access to pelvic cyst in the pouch of Douglas (figure 2). Packs soaked in scolicidal agent (10% povidone iodine) were placed around the cyst during the procedure. The cyst was adherent to right ureter and posterior surface of the uterus and required ureteric dissection in the ureteric canal. The cyst was removed intact without spillage. Exploration of the abdomen revealed another flaccid cyst 6×8 cm on the under surface of liver. One more pedunculated right subhepatic cyst arising from greater omentum and adherent to the colon was excised. The lumbar cyst anterior to right kidney was left in situ due to its proximity to renal vessels. Postoperative period was uneventful and the mother recovered well. Postpartum ultrasonography revealed calcified subphrenic (12×12×6 cm) cyst and the cyst anterior to right kidney (9×6 cm) in situ. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of hydatid cyst. Patient was discharged on tablet albendazole 15 mg/kg body weight daily for a further period of 6 weeks. She is on follow-up and continues to be asymptomatic.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative picture showing the large pelvic hydatid cyst posterior to uterus.

Discussion

Surgical treatment is the mainstay in management of hydatid disease and surgery is individualised according to the number and location of cysts, physiological condition of the patient and the presence of complications such as cyst infection and rupture. Frequently the site of hydatid cyst may be such as not to have any impact on pregnancy, for example, liver, kidney and spleen.1 If the cyst is located in the pelvis, problems are likely to manifest at the time of labour and delivery. There are earlier reports of pelvic hydatid cysts presenting with symptoms requiring urgent intervention.4

When patient presents with asymptomatic pelvic hydatid disease during antenatal period controversy arises whether to manage these patients solely on pharmacological therapy or perform immediate cyst excision.5 Surgery during pregnancy may be associated with increased intraoperative morbidity due to poor manoeuvrability due to the gravid uterus and also poses risk to the pregnancy in terms of miscarriage or preterm labour. On the other hand, if left in situ, the cyst may increase in size and may cause problems during labour. Management thus needs to be individualised.

In this case the patient opted for conservative management. The role of medical management in hydatid disease during pregnancy is at best limited. Albendazole is the drug of choice for hydatid disease and is a useful adjunct to surgical removal. Decrease in size and disappearance of daughter cysts with medical therapy has been documented.6 Although albendazole has been reported to be embryotoxic and teratogenic in animals, inadvertent exposure of pregnant women to Albendazole during mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis showed no increase in risk for gross congenital anomalies.7 As the period of gestation was already 18 weeks when treatment was started, teratogenicity was not a concern in our patient. Medical management did prove beneficial with disappearance of one cyst, regression in the size of the other cysts and calcification of one cyst. Moreover, there was no increase in the size of any of the cysts.

To conclude, asymptomatic hydatid disease complicating pregnancy presents with a management dilemma. Medical management with albendazole after the first trimester along with close monitoring for adverse drug reactions should be considered in patients not suitable or not willing to undergo surgery. Surgical excision of the cysts can be postponed and performed either postdelivery or simultaneously at the time of caesarean delivery. This approach optimises both obstetric and perinatal outcomes along with definitive management of the hydatid disease.

Learning points.

Hydatid disease complicating pregnancy is rare with an incidence of 1 in 20 000 to 1 in 30 000.

The disease has variable presentation ranging from asymptomatic disease to acute complications like rupture, anaphylaxis and obstructed labour.

Treatment should be individualised taking into consideration the site, size, number of cyst(s), the period of gestation and the patient's wishes.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Can D, Oztekin O, Oztekin O, et al. Hepatic and splenic cyst during pregnancy: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2003;268:239–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dede S, Dede H, Caliskan E, et al. Recurrent pelvic hydatid cyst obstructing labor, with a concomitant hepatic primary: a case report. J Reprod Med 2002;47:164–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, et al. Echinococcosis. Lancet 2003;362:1295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goswami D, Tempe A, Arora R, et al. Successful management of obstructed labor in a patient with multiple hydatid cysts. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002;83:600–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues G, Seetharam P. Management of hydatid disease (echinococcosis) in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2008;63:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris DL, Dykes PW, Marriner S, et al. Albendazole—objective evidence of response in human hydatid disease. J Am Med Assoc 1985;253:2053–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyapong JO, Chinbuth MA, Gyapong M. Inadvertent exposure of pregnant women to ivermectin and albendazole during mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis. J Rep Med Int Health 2003;8:1093–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]